Love vs. Risk: Women with Sickle Cell Disease Face Reproductive Decision-Making Dilemmas

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

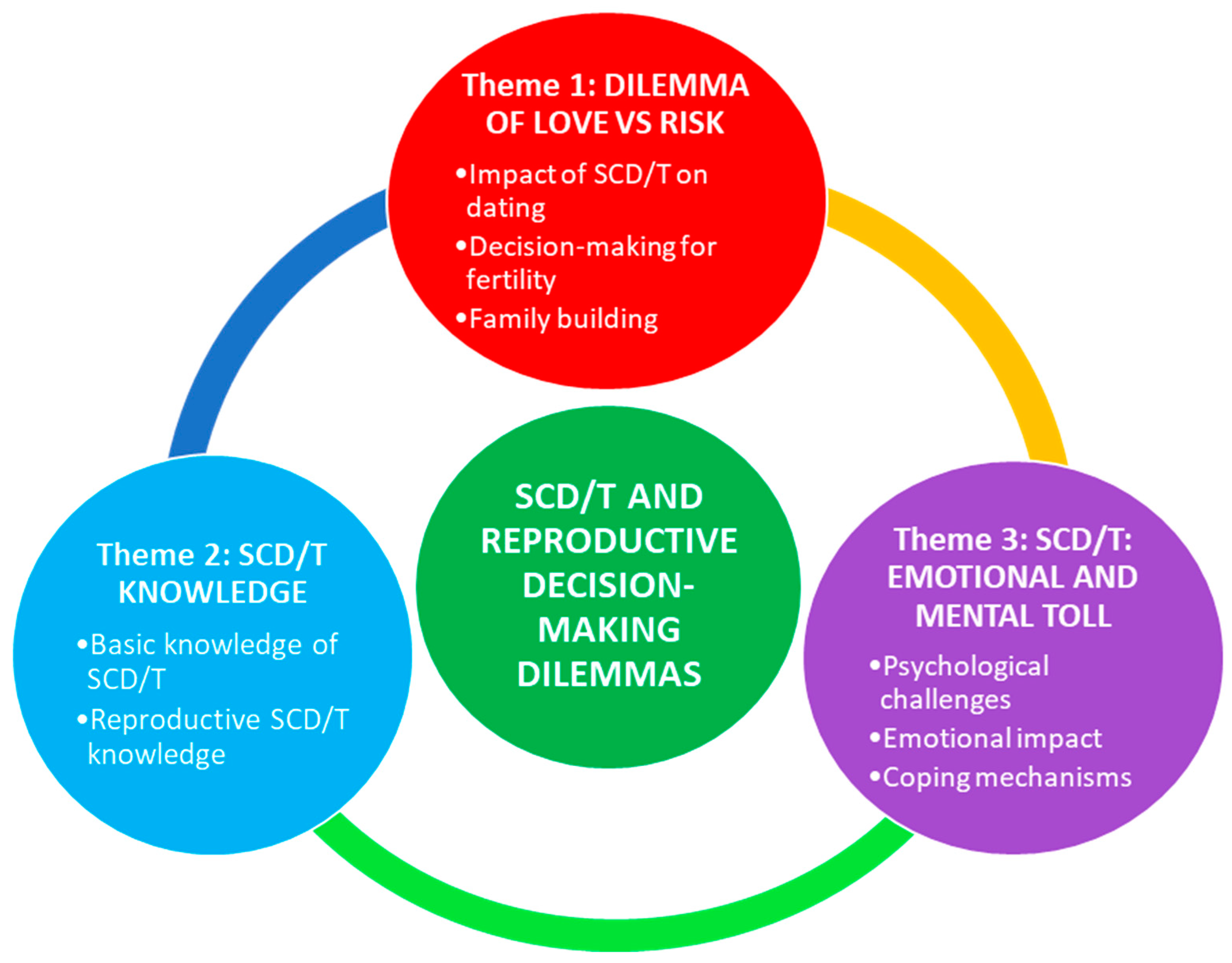

3. Results

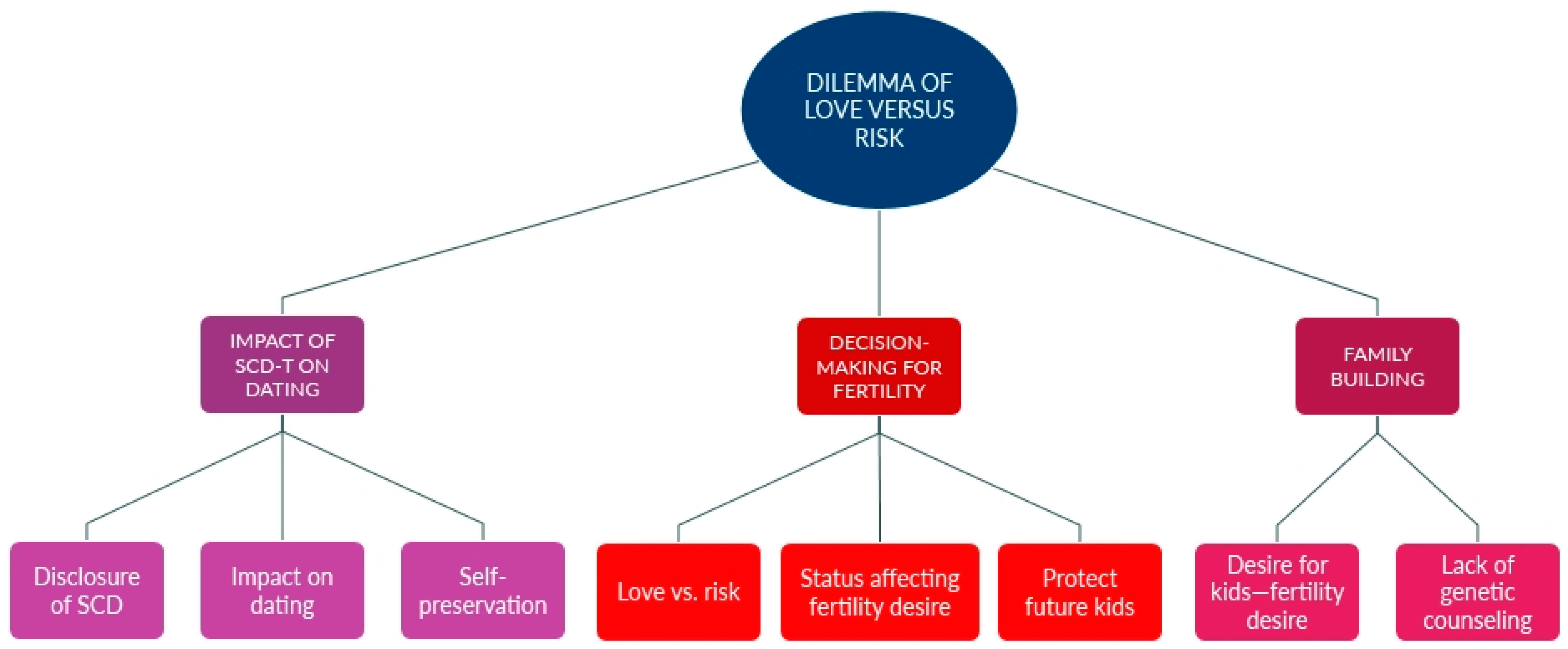

3.1. Dilemma of Love vs. Risk

“My last partner, yes. And I mean, we’re both super young, so we’re like, ‘Let’s hold on that.’ And if it does happen to, like we’ll adopt someone that’s a child that’s a couple months so we could like raise them.” (Participant #19, female).

“Would I take the risk for love and potentially put my child in literal pain, or walk away from that [relationship]?” (Participant #13, female).

“I’m on hydroxyurea, and I know that, while you’re on hydroxyurea, you can’t be pregnant, or it will hurt the baby.” (Participant #17, female).

“There is a very high incidence of maternal and fetal morbidity in people with sickle cell disease. So … planning fertility and, reproductive outcomes is extremely important and critical.” (Participant #10, HCP).

“I looked at my ex-husband and I said, “What do you want to do?” And he said, “I don’t want an abortion.” And I said, I didn’t either. And I told the counselor and they were adamant, ‘You have to terminate.’ And I was like, this is my body, this is my child, I am not terminating my child.” (Participant #4, caregiver).

“So then we had our second son, and the same thing. They told us that he had the trait.” (Participant #3, caregiver).

“… some of them have lost multiple [pregnancies], they’ve gone through multiple fetal demises, and it’s not healthy that they go through that often.” (Participant #6, caregiver).

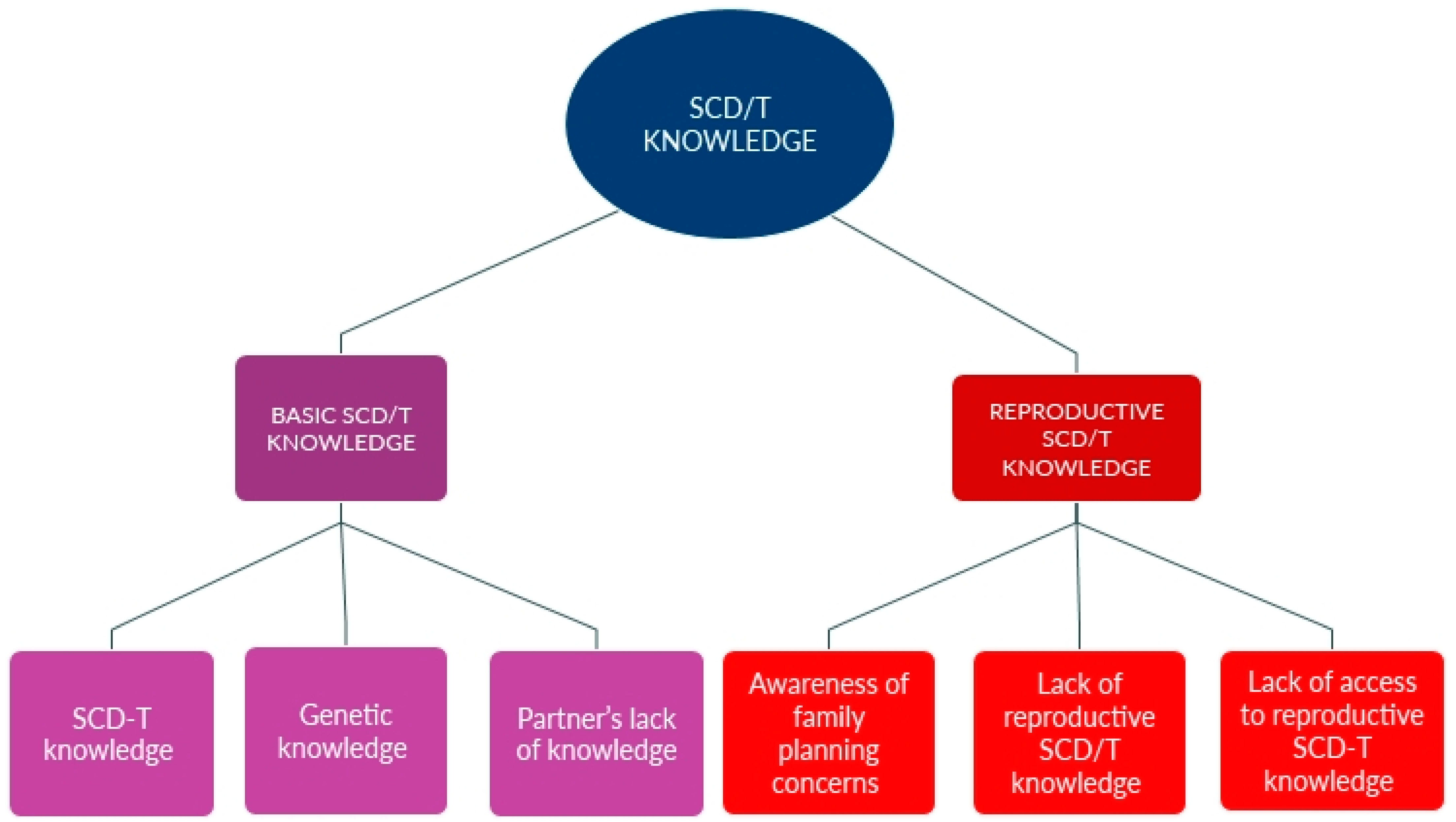

3.2. SCD/T Knowledge

“To have kids? I don’t think it’s that risky, because they say that sickle cell patients can’t have kids, but my cousins had kids, my best friend’s mom, she had three kids.” (Participant #20, female).

“For almost … their entire pregnancy, and then they come out, and they are diagnosed with something, and they are crying. So, it’s lack of knowledge and education….” (Participant #6, caregiver).

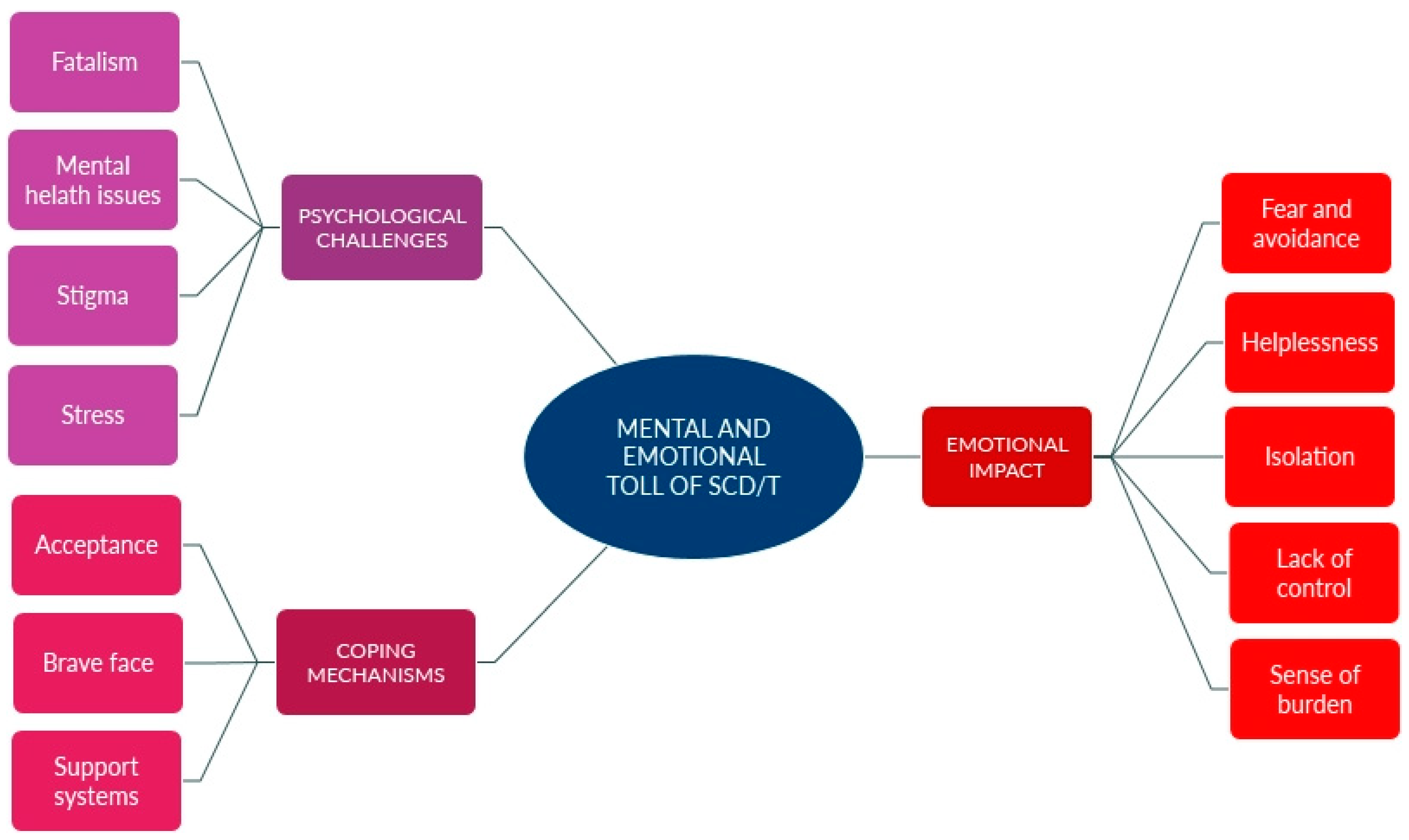

3.3. Mental and Emotional Toll of SCD/T

“Sickle cell is not just about the pain. It’s mentally, it’s emotionally. It’s the jobs that I was talking to you about. It’s about college, school, work. Because it’s like you can have a crisis, you can fall behind in school. Then you start to feel less of yourself and feel like you’re not smart enough. And the same with jobs. So I feel like it can really take a toll on your mental and your emotional state if you allow it to.” (Participant #8, female).

“I have one friend who was saying that she doesn’t know why I come with them places because I couldn’t walk as fast as them …. That’s why I decided to just stay at home and not do a lot of things with other people unless they understand.” (Participant #45).

“I don’t like for other people to see me in pain like that, or crying, or super drained, and fatigued, so I think that’s something that I just kind of kept to myself, for sure, too.” (Participant #17, female).

“I don’t really have friends like that, a lot of them don’t understand.” (Participant #20, female).

“Yeah, I don’t want them to see me as just sick, like all you see is my sickle cell. You don’t see the other side of me.” (Participant #17, female).

“So I always show like the strong face, like I’m okay.” (Participant #19, female).

“Like, stressing about having—whether I get sick or not.” (Participant #20, female).

“So I just feel like it’s more than just the disease itself. It opens a door for so much more [difficulties].” (Participant #14, female).

“I’ll say my friends that have kids with full-blown sickle cell, they too don’t--they don’t want to share. They don’t like to talk about it. They’ll tell me things in confidence and let it be like that. It’s not something that you want to say publicly.” (Participant #3, caregiver).

“I’ve heard words like ‘This isn’t someone coming in with a congenital condition.’ I hear ‘This is a sickler coming in with a new medical complaint.’ On the sign-outs, there are different words, like ‘sickler,’ like ‘pain seeker,’ like ‘needing opioid medication’ that are discussed.” (Participant #11, HCP).

4. Discussion

4.1. Discussion on the Dilemma of Love vs. Risk

4.2. Discussion on the SCD/T Knowledge

4.3. Discussion on the Mental and Emotional Toll of SCD/T

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Data & Statistics on Sickle Cell Disease. 6 July 2023. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/sickle-cell/data/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/sicklecell/data.html (accessed on 27 April 2024).

- Pecker, L.H.; Naik, R.P. The current state of sickle cell trait: Implications for reproductive and genetic counseling. Blood 2018, 132, 2331–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Desease Control and Prevention. What You Should Know About Sickle Cell Disease; CDC Division of Blood Disorders and Public Health Genomics, Ed.; CDC: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2024; p. 2.

- Bulgin, D.; Tanabe, P.; Jenerette, C. Stigma of sickle cell disease: A systematic review. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2018, 39, 675–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pecker, L.H.; Sharma, D.; Nero, A.; Paidas, M.J.; Ware, R.E.; James, A.H.; Smith-Whitley, K. Knowledge gaps in reproductive and sexual health in girls and women with sickle cell disease. Br. J. Haematol. 2021, 194, 970–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oteng-Ntim, E.; Meeks, D.; Seed, P.T.; Webster, L.; Howard, J.; Doyle, P.; Chappell, L.C. Adverse maternal and perinatal outcomes in pregnant women with sickle cell disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Blood J. Am. Soc. Hematol. 2015, 125, 3316–3325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villers, M.S.; Jamison, M.G.; De Castro, L.M.; James, A.H. Morbidity associated with sickle cell disease in pregnancy. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2008, 199, 125.e1–125.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Early, M.L.; Eke, A.C.; Gemmill, A.; Lanzkron, S.; Pecker, L.H. Comparisons of Severe Maternal Morbidity and Other Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes in Pregnant People with Sickle Cell Disease vs Anemia. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2254545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adesina, O.O.; Brunson, A.; Fisch, S.C.; Yu, B.; Mahajan, A.; Willen, S.M.; Keegan, T.H.; Wun, T. Pregnancy outcomes in women with sickle cell disease in California. Am. J. Hematol. 2023, 98, 440–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alayed, N.; Kezouh, A.; Oddy, L.; Abenhaim, H.A. Sickle cell disease and pregnancy outcomes: Population-based study on 8.8 million births. J. Perinat. Med. 2014, 42, 487–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canelón, S.P.; Butts, S.; Boland, M.R. Evaluation of Stillbirth Among Pregnant People with Sickle Cell Trait. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2134274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinerstein, C. Coercion or Choice? Reproductive Autonomy in Sickle Cell Disease Care; American Council on Science and Health: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Desine, S.; Eskin, L.; Bonham, V.L.; Koehly, L.M. Social support networks of adults with sickle cell disease. J. Genet. Couns. 2021, 30, 1418–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, L.R. The lived experience of childbearing: The lifelong impact. In The Maternal Health Crisis in America: Nursing Implications for Advocacy and Practice; Anderson, B.A., Roberts, L.R., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2019; p. 198. [Google Scholar]

- Frenn, M.; Whitehead, D.K. Health Promotion: Translating Evidence to Practice; FA Davis: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Viola, A.; Porter, J.; Shipman, J.; Brooks, E.; Valrie, C. A scoping review of transition interventions for young adults with sickle cell disease. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2021, 68, e29135. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Corbin, J.; Strauss, A. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Naeem, M.; Ozuem, W.; Howell, K.; Ranfagni, S. A step-by-step process of thematic analysis to develop a conceptual model in qualitative research. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2023, 22, 16094069231205789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Can I use TA? Should I use TA? Should I not use TA? Comparing reflexive thematic analysis and other pattern-based qualitative analytic approaches. Couns. Psychother. Res. 2021, 21, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladiran, O.-O. Exploring How Sickle Cell Disease Impacts the Selection of Romantic Partner and Reproductive Decision Making of Adults with Sickle Cell Disease Living in The United Kingdom; University of Sheffield: Sheffield, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Alsalman, M.; Alhamoud, H.; Alabdullah, Z.; Alsleem, R.; Almarzooq, Z.; Alsalem, F.; Alsulaiman, A.; Albeladi, A.; Alsalman, Z. Sickle cell disease knowledge and reproductive decisions: A Saudi cross-sectional study. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2023, 17, 761–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berghs, M.; Dyson, S.; Gabba, A.; Nyandemo, S.; Roberts, G.; Deen, G.; Thomas, I. “I want to become someone!” gender, reproduction and the moral career of motherhood for women with sickle cell disorders. Cult. Health Sex. 2023, 25, 633–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boodman, E. Coercive Care. A STAT Investigation 2024. Available online: https://www.statnews.com/coercive-care-sickle-cell-disease/ (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Thorpe, R.; Masser, B.; Coundouris, S.P.; Hyde, M.K.; Kruse, S.P.; Davison, T.E. The health impacts of blood donation: A systematic review of donor and non-donor perceptions. Blood Transfus. 2023, 22, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Li, L.; Li, Y.; Yang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yu, H.; Hou, M.; Li, W.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Z. The willingness and satisfaction to blood donation of the public in the minority area of China. Chin. J. Blood Transfus. 2019, 32, 1253–1256. [Google Scholar]

| ODDS RATIOS FOR COMPLICATIONS OF SICKLE CELL DISEASE THAT INCREASE MATERNAL AND FETAL HEALTH RISKS | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiomyopathy | 3.7 | ||

| Pulmonary HTN | 6.3 | ||

| Renal failure | 3.5-5.19 | ||

| Anemia | 90.1 | ||

| Substance abuse | 1 | ||

| REPRODUCTIVE COMPLICATIONS WITH SICKLE CELL DISEASE | |||

| Maternal Complications | OR | Perinatal Complications | OR |

| Cerebrovascular event | 2.0–10.9 | Gestational HTN and preeclampsia | 1.2–2.7 |

| Deep vein thrombosis | 2.5–13.6 | Eclampsia | 2.7–3.2 |

| Transfusions | 22.5 | Abruption | 1.6 |

| Postpartum hemorrhage | 0.5–2.3 | Antepartum bleeding | 1.7 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 1.7–14.35 | Preterm labor, preterm delivery | 1.1–2.2 |

| Pneumonia | 9.8 | Intrauterine growth restriction | 2.2–4.0 |

| Pyelonephritis | 1.3 | Intrauterine fetal death (stillbirth) | 1.1–26.8 |

| Postpartum infection | 1.4 | Gestational diabetes mellitus | 0.7–1.0 |

| Sepsis | 6.8–14.9 | Genitourinary tract infection | 2.3–6.8 |

| Systemic inflammatory response syndrome | 4.1–12.6 | ||

| Acute respiratory distress syndrome, mechanical ventilation | 6.3–12.2 | ||

| Hysterectomy | 2.3 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Roberts, L.R.; Fider, C.O.; Sahin, S.; Frederick, J.; Nation, I.; Montgomery, S. Love vs. Risk: Women with Sickle Cell Disease Face Reproductive Decision-Making Dilemmas. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 342. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22030342

Roberts LR, Fider CO, Sahin S, Frederick J, Nation I, Montgomery S. Love vs. Risk: Women with Sickle Cell Disease Face Reproductive Decision-Making Dilemmas. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(3):342. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22030342

Chicago/Turabian StyleRoberts, Lisa R., Carlene O. Fider, Safiye Sahin, Jayde Frederick, Ilsa Nation, and Susanne Montgomery. 2025. "Love vs. Risk: Women with Sickle Cell Disease Face Reproductive Decision-Making Dilemmas" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 3: 342. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22030342

APA StyleRoberts, L. R., Fider, C. O., Sahin, S., Frederick, J., Nation, I., & Montgomery, S. (2025). Love vs. Risk: Women with Sickle Cell Disease Face Reproductive Decision-Making Dilemmas. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(3), 342. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22030342