Which Risk Factors Matter More for Psychological Distress during the COVID-19 Pandemic? An Application Approach of Gradient Boosting Decision Trees

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Method

2.2. Study Area and Data Description

2.3. Variables Definition

2.3.1. Response Variable

2.3.2. Objective Predictors

2.3.3. Perceived Predictors

2.3.4. Health and Sociodemographic Predictors

2.4. Reliability and Validity

3. Results

3.1. Relatively Importance of Predictors

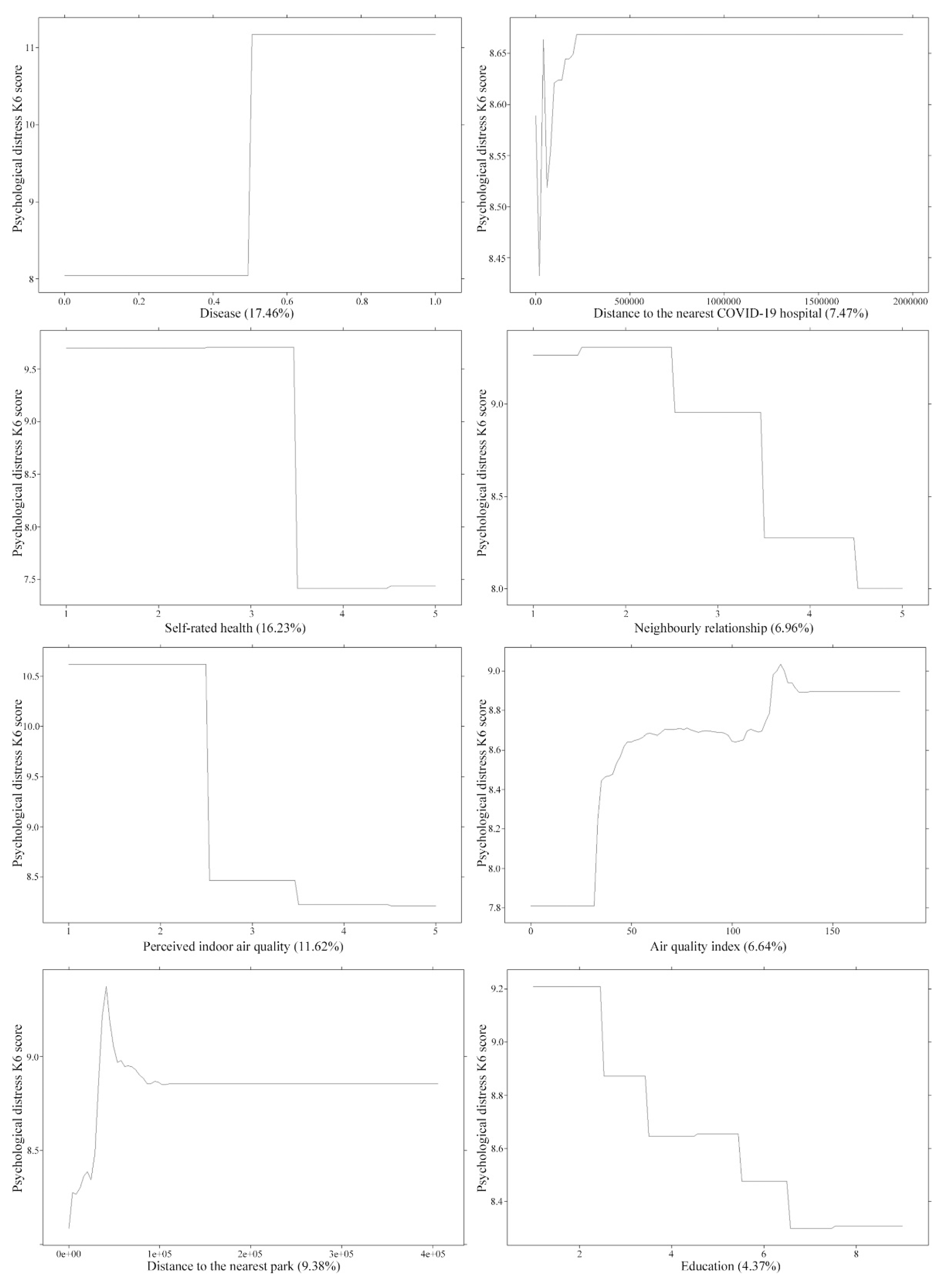

3.2. Association between High-Ranking Predictors and Psychological Distress

3.3. Gender Senstive Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings

4.2. Evidence on the Association between Risk Factors and the Level of Psychological Distress

4.3. Evidence from Gender Sensitive Analysis

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, Q.; Guan, X.; Wu, P.; Wang, X.; Zhou, L.; Tong, Y.; Ren, R.; Leung, K.S.; Lau, E.H.; Wong, J.Y. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Horby, P.W.; Hayden, F.G.; Gao, G.F. A novel coronavirus outbreak of global health concern. Lancet 2020, 395, 470–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhu, N.; Zhang, D.; Wang, W.; Li, X.; Yang, B.; Song, J.; Zhao, X.; Huang, B.; Shi, W.; Lu, R. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Zheng, D.; Liu, J.; Gong, Y.; Guan, Z.; Lou, D. Depression and anxiety among adolescents during COVID-19: A cross-sectional study. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vindegaard, N.; Benros, M.E. COVID-19 pandemic and mental health consequences: Systematic review of the current evidence. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 89, 531–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, W.; Fang, Z.; Hou, G.; Han, M.; Xu, X.; Dong, J.; Zheng, J. The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 287, 112934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, M.S.; Ferdous, M.Z.; Potenza, M.N. Panic and generalized anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic among Bangladeshi people: An online pilot survey early in the outbreak. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 276, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghanibashi-Mansourieh, A. Assessing the anxiety level of Iranian general population during COVID-19 outbreak. Asian J. Psychiatry 2020, 51, 102076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barzilay, R.; Moore, T.M.; Greenberg, D.M.; DiDomenico, G.E.; Brown, L.A.; White, L.K.; Gur, R.C.; Gur, R.E. Resilience, COVID-19-related stress, anxiety and depression during the pandemic in a large population enriched for healthcare providers. Transl. Psychiatry 2020, 10, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Jones, C.; Dunse, N. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and psychological distress in China: Does neighbourhood matter? Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 759, 144203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kujawa, A.; Green, H.; Compas, B.E.; Dickey, L.; Pegg, S. Exposure to COVID-19 pandemic stress: Associations with depression and anxiety in emerging adults in the United States. Depress. Anxiety 2020, 37, 1280–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazza, C.; Ricci, E.; Biondi, S.; Colasanti, M.; Ferracuti, S.; Napoli, C.; Roma, P. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Italian people during the COVID-19 pandemic: Immediate psychological responses and associated factors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Shen, B.; Zhao, M.; Wang, Z.; Xie, B.; Xu, Y. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: Implications and policy recommendations. Gen. Psychiatry 2020, 33, e100213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Joob, B.; Wiwanitkit, V. Traumatization in medical staff helping with COVID-19 control. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, L.; Ma, S.; Chen, M.; Yang, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, R.; Yao, L.; Bai, H.; Cai, Z.; Yang, B.X. Impact on mental health and perceptions of psychological care among medical and nursing staff in Wuhan during the 2019 novel coronavirus disease outbreak: A cross-sectional study. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 87, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, X.; Fu, W.; Liu, X.; Luo, Z.; Wang, R.; Zhou, N.; Yan, S.; Lv, C. Mental health status of medical staff in emergency departments during the Coronavirus disease 2019 epidemic in China. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 88, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, B.Y.; Chew, N.W.; Lee, G.K.; Jing, M.; Goh, Y.; Yeo, L.L.; Zhang, K.; Chin, H.-K.; Ahmad, A.; Khan, F.A. Psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on health care workers in Singapore. Ann. Intern. Med. 2020, 173, 317–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Husky, M.M.; Kovess-Masfety, V.; Swendsen, J.D. Stress and anxiety among university students in France during Covid-19 mandatory confinement. Compr. Psychiatry 2020, 102, 152191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Lorca, M.; Martínez-Lorca, A.; Criado-Álvarez, J.J.; Armesilla, M.D.C. The fear of COVID-19 scale: Validation in Spanish university students. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 113350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, X.; Zheng, K.; Tang, M.; Kong, F.; Zhou, J.; Diao, L.; Wu, S.; Jiao, P.; Su, T.; Dong, Y. Prevalence and factors associated with depression and anxiety of hospitalized patients with COVID-19. MedRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Muruganandam, P.; Neelamegam, S.; Menon, V.; Alexander, J.; Chaturvedi, S.K. COVID-19 and Severe Mental Illness: Impact on patients and its relation with their awareness about COVID-19. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 291, 113265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Duan, Z.; Ma, Z.; Mao, Y.; Li, X.; Wilson, A.; Qin, H.; Ou, J.; Peng, K.; Zhou, F. Epidemiology of mental health problems among patients with cancer during COVID-19 pandemic. Transl. Psychiatry 2020, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosley, S. Environmental history of air pollution and protection. In The Basic Environmental History; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 143–169. [Google Scholar]

- Brunekreef, B.; Holgate, S.T. Air pollution and health. Lancet 2002, 360, 1233–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kioumourtzoglou, M.-A.; Power, M.C.; Hart, J.E.; Okereke, O.I.; Coull, B.A.; Laden, F.; Weisskopf, M.G. The association between air pollution and onset of depression among middle-aged and older women. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2017, 185, 801–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Power, M.C.; Kioumourtzoglou, M.-A.; Hart, J.E.; Okereke, O.I.; Laden, F.; Weisskopf, M.G. The relation between past exposure to fine particulate air pollution and prevalent anxiety: Observational cohort study. BMJ 2015, 350, h1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sass, V.; Kravitz-Wirtz, N.; Karceski, S.M.; Hajat, A.; Crowder, K.; Takeuchi, D. The effects of air pollution on individual psychological distress. Health Place 2017, 48, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinault, L.; Thomson, E.M.; Christidis, T.; Colman, I.; Tjepkema, M.; van Donkelaar, A.; Martin, R.V.; Hystad, P.; Shin, H.; Crouse, D.L. The association between ambient air pollution concentrations and psychological distress. Health Rep. 2020, 31, 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- He, G.; Chen, Y.; Wang, S.; Dong, Y.; Ju, G.; Chen, B. The Association between PM2.5 and Depression in China. Dose-Response 2020, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zijlema, W.L.; Wolf, K.; Emeny, R.; Ladwig, K.-H.; Peters, A.; Kongsgård, H.; Hveem, K.; Kvaløy, K.; Yli-Tuomi, T.; Partonen, T. The association of air pollution and depressed mood in 70,928 individuals from four European cohorts. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2016, 219, 212–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- WorsePolluted Indoor Air Pollution. Available online: https://www.worstpolluted.org/projects_reports/display/59 (accessed on 5 March 2021).

- EPA. An Introduction to Indoor Air Quality. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/indoor-air-quality-iaq/introduction-indoor-air-quality (accessed on 5 March 2021).

- Kim, S.; Senick, J.A.; Mainelis, G. Sensing the invisible: Understanding the perception of indoor air quality among children in low-income families. Int. J. Child Comput. Interact. 2019, 19, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunleavy, G.; Bajpai, R.; Tonon, A.C.; Cheung, K.L.; Thach, T.-Q.; Rykov, Y.; Soh, C.-K.; de Vries, H.; Car, J.; Christopoulos, G. Prevalence of psychological distress and its association with perceived indoor environmental quality and workplace factors in under and aboveground workplaces. Build. Environ. 2020, 175, 106799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Li, Z. Does where you live matter to your health? Investigating factors that influence the self-rated health of urban and rural Chinese residents: Evidence drawn from Chinese general social survey data. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2017, 15, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sønderskov, K.M.; Dinesen, P.T.; Santini, Z.I.; Østergaard, S.D. The depressive state of Denmark during the COVID-19 pandemic. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2020, 32, 226–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, H.; Xia, Q.; Xiong, Z.; Li, Z.; Xiang, W.; Yuan, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z. The psychological distress and coping styles in the early stages of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic in the general mainland Chinese population: A web-based survey. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0233410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Pan, R.; Wan, X.; Tan, Y.; Xu, L.; Ho, C.S.; Ho, R.C. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rahman, M.A.; Hoque, N.; Alif, S.M.; Salehin, M.; Islam, S.M.S.; Banik, B.; Sharif, A.; Nazim, N.B.; Sultana, F.; Cross, W. Factors associated with psychological distress, fear and coping strategies during the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia. Glob. Health 2020, 16, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sfendla, A.; Hadrya, F. Factors associated with psychological distress and physical activity during the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Secur. 2020, 18, 444–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, C.; Wang, D.; Ma, X.; Li, H. Predicting short-term subway ridership and prioritizing its influential factors using gradient boosting decision trees. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yin, C.; Cao, J.; Sun, B. Examining non-linear associations between population density and waist-hip ratio: An application of gradient boosting decision trees. Cities 2020, 107, 102899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R.; Friedman, J. The Elements of Statistical Learning: Data Mining, Inference, and Prediction; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, X.; Ding, C.; Luan, S.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y. Prioritizing influential factors for freeway incident clearance time prediction using the gradient boosting decision trees method. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2017, 18, 2303–2310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, J.H. Greedy function approximation: A gradient boosting machine. Ann. Stat. 2001, 29, 1189–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schonlau, M. Boosted regression (boosting): An introductory tutorial and a Stata plugin. Stata J. 2005, 5, 330–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L.; Friedman, J.; Stone, C.J.; Olshen, R.A. Classification and Regression Trees; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler, R.C.; Andrews, G.; Colpe, L.J.; Hiripi, E.; Mroczek, D.K.; Normand, S.L.T.; Walters, E.E.; Zaslavsky, A.M. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol. Med. 2002, 32, 959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fushimi, M.; Saito, S.; Shimizu, T.; Kudo, Y.; Seki, M.; Murata, K. Prevalence of psychological distress, as measured by the Kessler 6 (K6), and related factors in Japanese employees. Community Ment. Health J. 2012, 48, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, T.D.; Burdette, A.M.; Hale, L. Neighborhood disorder, sleep quality, and psychological distress: Testing a model of structural amplification. Health Place 2009, 15, 1006–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugolini, F.; Massetti, L.; Pearlmutter, D.; Sanesi, G. Usage of urban green space and related feelings of deprivation during the COVID-19 lockdown: Lessons learned from an Italian case study. Land Use Policy 2021, 105, 105437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Cao, L.; Xie, J.; Yu, Y.; Chen, A.; Huang, F. Using social media data to assess the impact of COVID-19 on mental health in China. In Psychological Medicine; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Breslau, N.; Roth, T.; Rosenthal, L.; Andreski, P. Sleep disturbance and psychiatric disorders: A longitudinal epidemiological study of young adults. Biol. Psychiatry 1996, 39, 411–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, D.; Mitrou, F.; Zubrick, S.R. Non-specific psychological distress, smoking status and smoking cessation: United States National Health Interview Survey 2005. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Marchand, A.; Demers, A.; Durand, P.; Simard, M. Occupational variations in drinking and psychological distress: A multilevel analysis. Work 2003, 21, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Meerlo, P.; Sgoifo, A.; Suchecki, D. Restricted and disrupted sleep: Effects on autonomic function, neuroendocrine stress systems and stress responsivity. Sleep Med. Rev. 2008, 12, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.; Kelly, B. Emotional dimensions of chronic disease. West. J. Med. 2000, 172, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Weyerer, S.; Kupfer, B. Physical exercise and psychological health. Sports Med. 1994, 17, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronbach, L.J. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 1951, 16, 297–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory 3E; Tata McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- George, D. SPSS for Windows Step by Step: A Simple Study Guide and Reference, 17.0 Update, 10/e; Pearson Education: Chennai, India, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bolarinwa, O.A. Principles and methods of validity and reliability testing of questionnaires used in social and health science researches. Niger. Postgrad. Med. J. 2015, 22, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Greenwell, B.; Boehmke, B.; Cunningham, J.; GBM, D. gbm: Generalized Boosted Regression Models. R Package Version 2.1. 5. 2019. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/package=gbm (accessed on 12 January 2020).

- Wang, X.; Shao, C.; Yin, C.; Guan, L. Disentangling the comparative roles of multilevel built environment on body mass index: Evidence from China. Cities 2021, 110, 103048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.; Zhou, T.; Lei, S.; Wen, Y.; Htun, T.T. Effects of urban green spaces on residents’ well-being. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2019, 21, 2793–2809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Liu, S.; Sun, Y.; Liu, Y.; Beazley, R.; Hou, X. Assessing NO2-related health effects by non-linear and linear methods on a national level. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 744, 140909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dzhambov, A.M.; Dimitrova, D.D. Urban green spaces’ effectiveness as a psychological buffer for the negative health impact of noise pollution: A systematic review. Noise Health 2014, 16, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Li, C.; Kwan, M.-P.; Kou, L.; Chai, Y. Assessing personal noise exposure and its relationship with mental health in Beijing based on individuals’ space-time behavior. Environ. Int. 2020, 139, 105737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Dijst, M.; Faber, J.; Helbich, M. Using structural equation modeling to examine pathways between perceived residential green space and mental health among internal migrants in China. Environ. Res. 2020, 183, 109121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, R.; Grekousis, G.; Liu, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Li, Z. Neighbourhood greenness and mental wellbeing in Guangzhou, China: What are the pathways? Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 190, 103602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, R.; Xiao, Y.; Huang, B.; Chen, H.; Li, Z. Exploring the linkage between greenness exposure and depression among Chinese people: Mediating roles of physical activity, stress and social cohesion and moderating role of urbanicity. Health Place 2019, 58, 102168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Yang, B.; Yao, Y.; Bloom, M.S.; Feng, Z.; Yuan, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liu, P.; Wu, W.; Lu, Y. Residential greenness, air pollution and psychological well-being among urban residents in Guangzhou, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 711, 134843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Liu, Y.; Xue, D.; Yao, Y.; Liu, P.; Helbich, M. Cross-sectional associations between long-term exposure to particulate matter and depression in China: The mediating effects of sunlight, physical activity, and neighborly reciprocity. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 249, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuntsche, E.; Wicki, M.; Windlin, B.; Roberts, C.; Gabhainn, S.N.; van der Sluijs, W.; Aasvee, K.; de Matos, M.G.; Dankulincová, Z.; Hublet, A. Drinking motives mediate cultural differences but not gender differences in adolescent alcohol use. J. Adolesc. Health 2015, 56, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, L.M.; Litt, D.M.; Stewart, S.H. Drinking to cope with the pandemic: The unique associations of COVID-19-related perceived threat and psychological distress to drinking behaviors in American men and women. Addict. Behav. 2020, 110, 106532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Liu, H.; Ren, Z.; Xiong, W.; He, M.; Fan, X.; Guo, X.; Li, X.; Shi, H.; Zha, S. Gender difference in the association of coping styles and social support with psychological distress among patients with end-stage renal disease. PeerJ 2020, 8, e8713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shechter, A.; Diaz, F.; Moise, N.; Anstey, D.E.; Ye, S.; Agarwal, S.; Birk, J.L.; Brodie, D.; Cannone, D.E.; Chang, B. Psychological distress, coping behaviors, and preferences for support among New York healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2020, 66, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Definition | N | Mean/% |

|---|---|---|---|

| Response Variable | |||

| K6 Score (0–30) (mean (SD)) | The Kessler Psychological Distress Scale, K6 | 937 | 9.3 |

| Predictors | |||

| Sex (n, %) | Female as the reference category | ||

| Male | 325 | 65.3 | |

| Female | 612 | 34.7 | |

| Age (n, %) | |||

| 18–24 | 172 | 18.4 | |

| 25–34 | 381 | 40.7 | |

| 35–44 | 238 | 25.4 | |

| 45–54 | 101 | 10.8 | |

| 55–64 | 36 | 3.8 | |

| 65–74 | 7 | 0.8 | |

| 75+ | 2 | 0.2 | |

| Marital Status (n, %) | Unmarried as the reference category | ||

| Married | 570 | 60.8 | |

| Unmarried | 367 | 39.2 | |

| Education (n, %) | |||

| Illiteracy | 29 | 3.1 | |

| Primary | 72 | 7.7 | |

| Junior high school | 181 | 19.3 | |

| Technical secondary school | 137 | 14.6 | |

| High school | 132 | 14.1 | |

| College | 156 | 16.7 | |

| Undergraduate | 169 | 18.0 | |

| Master | 49 | 5.2 | |

| PhD and above | 12 | 1.3 | |

| Household Income (n, %) | |||

| Monthly earnings of 3000 yuan | 245 | 26.2 | |

| Monthly earning 3000–10,000 yuan | 368 | 39.3 | |

| Monthly earning 10,000–20,000 yuan | 183 | 19.5 | |

| Monthly earning 20,000–30,000 yuan | 69 | 7.4 | |

| Monthly earning 30,000–50,000 yuan | 29 | 3.1 | |

| Monthly earning of 50,000 yuan | 43 | 4.6 | |

| Smoke (n, %) | |||

| Current smoker | 203 | 21.7 | |

| Non-smoker | 734 | 78.3 | |

| Drink (n, %) | |||

| Current drinker | 188 | 20.1 | |

| Non-current drinker | 749 | 79.9 | |

| Physical exercise (n, %) | |||

| Never | 211 | 22.5 | |

| Physical activity only once per week | 255 | 27.2 | |

| Physical activity 2–4 times per week | 295 | 31.5 | |

| Physical activity 5–7 times per week | 119 | 12.7 | |

| Physical activity more than 7 times per week | 57 | 6.1 | |

| Disease (n, %) | |||

| Have a chronic disease | 178 | 81 | |

| No chronic disease | 759 | 19 | |

| Self-rated health (n, %) | |||

| Extremely poor health | 35 | 3.7 | |

| Poor health | 97 | 10.4 | |

| Neutral | 360 | 38.4 | |

| Good health | 304 | 32.4 | |

| Extremely good health | 141 | 15.1 | |

| Neighborhood (n, %) | |||

| Extremely unsatisfied with the neighborly relationship | 44 | 4.7 | |

| Unsatisfied with the neighborly relationship | 89 | 9.5 | |

| Neutral | 353 | 37.7 | |

| Satisfied with the neighborly relationship | 334 | 35.7 | |

| Extremely satisfied with the neighborly relationship | 117 | 12.5 | |

| Perception of the indoor air quality (n, %) | |||

| Extremely bad indoor air quality | 41 | 4.4 | |

| Bad indoor air quality | 104 | 11.1 | |

| Neutral | 309 | 33.0 | |

| Good indoor air quality | 367 | 39.2 | |

| Extremely good indoor air quality | 16 | 12.3 | |

| Perception of overall environment quality (n, %) | |||

| Environments maintain in very poor quality | 52 | 5.6 | |

| Environments maintain in poor quality | 123 | 13.1 | |

| Neutral | 405 | 43.2 | |

| Environments maintain in good quality | 263 | 28.1 | |

| Environments maintain in very good quality | 94 | 10.0 | |

| Perception of distance to the COVID-19 hospital | |||

| Very far, at least an hour’s drive | 205 | 21.9 | |

| Far, at least half hour’s drive | 348 | 37.1 | |

| Close, at least 10 min to 30 min drive | 306 | 32.7 | |

| Very close, 5 min drive | 78 | 8.3 | |

| AQI (mean (SD)) | Air quality index | 937 | 81.1 |

| Distance to the park (mean (SD), KM) | Direct distance from the residence to the nearest park | 927 | 37.8 |

| Distance to the hospital (mean (SD), KM) | Direct distance from the residence to the nearest hospital | 937 | 67.1 |

| Predictors | Relative Importance (%) | Rank |

|---|---|---|

| Health predictors | Total 42.32 | |

| Disease | 17.46 | 1 |

| Self-rated health | 16.23 | 2 |

| Smoke | 3.45 | 9 |

| Drink | 3.14 | 10 |

| Physical exercise | 2.04 | 13 |

| Objective predictors | Total 23.49 | |

| Distance to nearest parks | 9.38 | 4 |

| Distance to the nearest COVID-19 hospital | 7.47 | 5 |

| Air quality index (AQI) | 6.64 | 7 |

| Sociodemographic predictors | Total 17.91 | |

| Neighbourly relationship | 6.96 | 6 |

| Education attainment level | 4.37 | 8 |

| Age | 2.69 | 12 |

| Marital status | 1.45 | 15 |

| Household Income | 1.03 | 16 |

| Urban | 0.89 | 17 |

| Gender | 0.52 | 18 |

| Perceived predictors | Total 16.26 | |

| Perceived indoor air quality | 11.62 | 3 |

| Perceived distance to COVID-19 hospital | 2.71 | 11 |

| Perceived environment | 1.93 | 14 |

| Predictors | Men | Women | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relative Importance (%) | Rank | Relative Importance (%) | Rank | |

| Health predictors | Total 31.31 | Total 32.05 | ||

| Disease | 16.87 | 1 | 3.18 | 9 |

| Self -rated health | 9.25 | 4 | 25.20 | 1 |

| Smoke | 1.56 | 12 | 0.75 | 15 |

| Drink | 0.63 | 17 | 0.80 | 14 |

| Physical exercise | 3.00 | 10 | 2.12 | 12 |

| Objective predictors | Total 25.10 | Total 32.01 | ||

| Distance to nearest parks | 6.47 | 7 | 8.82 | 5 |

| Distance to the nearest COVID-19 hospital | 8.89 | 5 | 14.21 | 2 |

| Air quality index (AQI) | 9.74 | 3 | 8.98 | 4 |

| Sociodemographic predictors | Total 27.57 | Total 14.80 | ||

| Neighborly relationship | 16.7 | 2 | 2.43 | 10 |

| Education attainment level | 5.05 | 9 | 4.65 | 7 |

| Age | 1.33 | 13 | 4.58 | 8 |

| Marital status | 0.97 | 16 | 0.28 | 17 |

| Household Income | 2.33 | 11 | 2.35 | 11 |

| Urban | 1.19 | 15 | 0.51 | 16 |

| Perceived predictors | Total 18.93 | Total 21.13 | ||

| Perceived indoor air quality | 1.20 | 14 | 13.67 | 3 |

| Perceived distance to COVID-19 hospital | 5.98 | 8 | 1.25 | 13 |

| Perceived environment | 8.84 | 6 | 6.21 | 6 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, Y.; Liu, Y. Which Risk Factors Matter More for Psychological Distress during the COVID-19 Pandemic? An Application Approach of Gradient Boosting Decision Trees. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5879. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18115879

Chen Y, Liu Y. Which Risk Factors Matter More for Psychological Distress during the COVID-19 Pandemic? An Application Approach of Gradient Boosting Decision Trees. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(11):5879. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18115879

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Yiyi, and Ye Liu. 2021. "Which Risk Factors Matter More for Psychological Distress during the COVID-19 Pandemic? An Application Approach of Gradient Boosting Decision Trees" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 11: 5879. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18115879

APA StyleChen, Y., & Liu, Y. (2021). Which Risk Factors Matter More for Psychological Distress during the COVID-19 Pandemic? An Application Approach of Gradient Boosting Decision Trees. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(11), 5879. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18115879