Interpersonal Psychotherapy to Reduce Psychological Distress in Perinatal Women: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Background

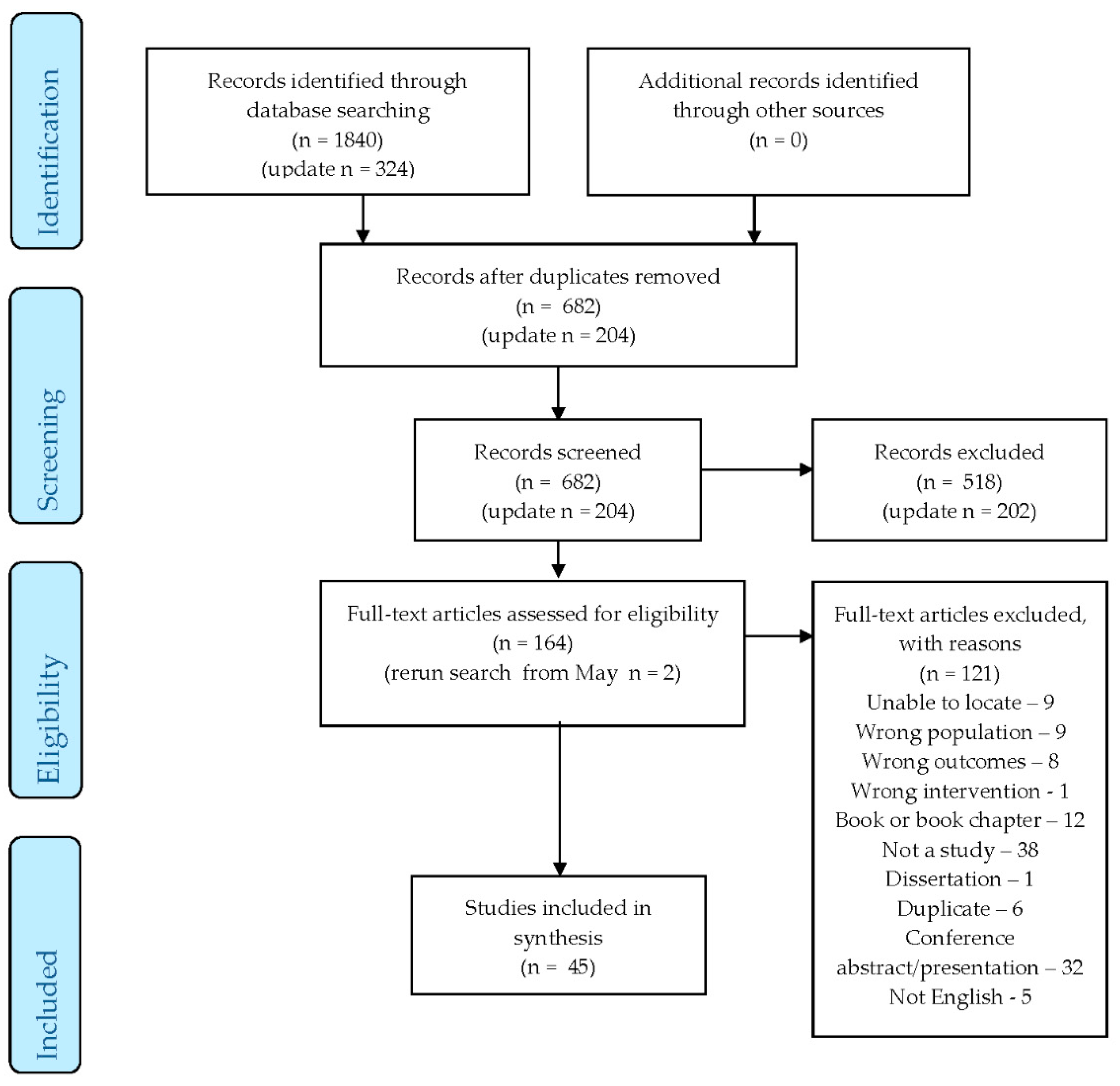

2. Methods

2.1. Protocol and Registration

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Participants

2.4. Study Design

2.5. Interventions

2.6. Comparator

2.7. Information Sources and Search Strategy

2.8. Screening of Studies

2.9. Risk of Bias in Individual Studies

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Included Studies

3.2. Prevention Studies

3.3. Treatment Studies

3.4. Change in Depressive Symptoms Between Treatment and Comparison Groups

3.5. Change in Anxiety Symptoms Between Treatment and Comparison Groups

3.6. Change in Stress Symptoms Between Treatment and Comparison Groups

3.7. Change in Relationship Quality Between Treatment and Comparison Groups

3.8. Change in Social Support Between Treatment and Comparison Groups

3.9. Change in Attachment Levels Between Treatment and Comparison Groups

3.10. Change in the Level of Adjustment Between Treatment and Comparison Groups

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths

4.2. Limitations

4.3. Research Implications

4.4. Clinical Implications

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

List of Abbreviations

| ANRQ | Antenatal Risk Questionnaire |

| AQS | Attachment Style Questionnaire |

| BAI | Beck Anxiety Inventory |

| BDI | Beck Depression Inventory |

| BDI-II | Beck Depression Inventory |

| Brief-STAI | Brief State-Trait Anxiety Inventory |

| CAGE-AID | Questionnaire for Drug and Alcohol Addiction Screening |

| CBT | Cognitive Behavioral Therapy |

| CBQ | Child Behavior Questionnaire |

| CES-D | Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale |

| CIDI | Composite International Diagnostic Interview |

| CNM-IPT | Certified Nurse-Midwife Telephone Administered Interpersonal Psychotherapy |

| CSQ | Cooper Survey Questionnaire |

| CTS2 | Revised Conflict Tactic Scale |

| CWS | Cambridge Worry Scale |

| DAS | Dyadic Adjustment Scale |

| DASS-21 | Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale—21 items |

| DIS | Diagnostic Interview Schedule |

| DLC | Difficult Life Circumstances |

| DSM-IV | Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition |

| DSM-IV-NP | Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition, non patient version |

| EAS | Emotional Availability Scale |

| ECR | Experiences in Close Relationships Scale |

| ECR-R | Experiences in Close Relationships Revised Scale |

| EPDS | Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale |

| EPDS-P | Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale for Partners |

| EFCT | Emotional Focused Couples Therapy |

| EPHPP | Effective Public Health Practice Project |

| GAF | Global Assessment of Functioning |

| GHQ | General Health Questionnaire |

| HADS | Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale |

| HAM-A | Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale |

| HAM-D | Hamilton Depression Rating Scale |

| HSC | Hopkins Symptoms Checklist |

| HRSD | Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (also written as HAM-D) |

| IBQ | Infant Behavior Questionnaire |

| ICD | International Classification of Disease |

| ICMJE | International Committee of Medical Journal Editors |

| IDD | Inventory of Diagnose Depression |

| IIP | Inventory of Interpersonal Problems |

| IPT | Interpersonal Psychotherapy |

| IPT-G | Interpersonal Psychotherapy for Groups |

| LIFE | Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Evaluation |

| LIFE-R | Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Evaluation Revised |

| LQ | Leverton Questionnaire |

| MAI | Maternal Attachment Inventory |

| MCMI-II | Millon Clinical Multiaxial Inventory |

| MDD | Major Depressive Disorder |

| MFB | Mindfulness Based |

| MINI | MINI-International Neuropsychiatric Interview |

| M-ITG | Mother-Infant Therapy Group |

| MSSS | Maternity Social Support Scale |

| OT | Open Trial |

| PLC-C | Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Checklist–Civilian Version |

| PES | Peripartum Events Scale |

| PHQ | Patient Health Questionnaire |

| PHQ-9 Questionnaire Revised | Patient Health |

| PPAQ | Postpartum Adjustment Questionnaire |

| PPD | Postpartum Depression |

| PRISMA-P | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses Protocols |

| PSI | Parenting Stress Index |

| PSOC | Parenting Sense of Competence Scale |

| PSOC-E | Parenting Sense of Competence with Efficacy Scale |

| PSR | Psychiatric Status Rating |

| QRT | Quasi-Randomized Controlled Trial |

| RCT | Randomized Controlled Trial |

| ROSE | Reach out, Stand Strong |

| SAS | Social Adjustment Scale |

| SAS-SR | Social Adjustment Scale Self Report |

| SCID | Structured Clinical Interview for DSM |

| SCID-I | Structured Clinical Interview for DSM I |

| SCID-IV | Structured Clinical Interview for DSM IV |

| SCL-90 | Symptoms Checklist 90 Questions |

| SSQ-R | School Situations Questionnaire-Revised |

| STAI | State-Trait Anxiety Inventory |

| STAXI | State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory |

| SUD | Substance Use Disorders |

| TAU | Treatment as Usual |

| TSR | Treatment Services Review |

| WSAS | Weinberg Screening Affective Scales |

| WLC | Waitlist Control |

References

- Huizink, A.C.; Menting, B.; De Moor, M.H.M.; Verhage, M.L.; Kunseler, F.C.; Schuengel, C.; Oosterman, M. From prenatal anxiety to parenting stress: A longitudinal study. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2017, 20, 663–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashford, M.T.; Olander, E.K.; Ayers, S. Computer-or web-based interventions for perinatal mental health: A systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 197, 134–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Göbel, A.; Stuhrmann, L.Y.; Harder, S.; Schulte-Markwort, M.; Mudra, S. The association between maternal-fetal bonding and prenatal anxiety: An explanatory analysis and systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 239, 313–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, M.V.; Shao, L.; Howell, H.; Lin, H.; Yonkers, K.A. Perinatal depression and birth outcomes in a Healthy Start project. Matern. Child Health J. 2011, 15, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biaggi, A.; Conroy, S.; Pawlby, S.; Pariante, C.M. Identifying the women at risk of antenatal anxiety and depression: A systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 191, 62–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomfohr, L.M.; Buliga, E.; Letourneau, N.L.; Campbell, T.S.; Giesbrecht, G.F. Trajectories of Sleep Quality and Associations with Mood during the Perinatal Period. Sleep 2015, 38, 1237–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kingston, D.; Austin, M.P.; Hegadoren, K.; McDonald, S.; Lasiuk, G.; McDonald, S.; Heaman, M.; Biringer, A.; Sword, W.; Giallo, R.; et al. Study protocol for a randomized, controlled, superiority trial comparing the clinical and cost- effectiveness of integrated online mental health assessment-referral-care in pregnancy to usual prenatal care on prenatal and postnatal mental health and infant health and development: The Integrated Maternal Psychosocial Assessment to Care Trial (IMPACT). Trials 2014, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loughnan, S.A.; Newby, J.M.; Haskelberg, H.; Mahoney, A.; Kladnitski, N.; Smith, J.; Black, E.; Holt, C.; Milgrom, J.; Austin, M.-P. Internet-based cognitive behavioural therapy (iCBT) for perinatal anxiety and depression versus treatment as usual: Study protocol for two randomised controlled trials. Trials 2018, 19, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, A.; Pearson, R.M.; Goodman, S.H.; Rapa, E.; Rahman, A.; McCallum, M.; Howard, L.M.; Pariante, C.M. Effects of perinatal mental disorders on the fetus and child. Lancet 2014, 384, 1800–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasheen, C.; Richardson, G.A.; Fabio, A. A systematic review of the effects of postnatal maternal anxiety on children. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2010, 13, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horwitz, S.M.; Briggs-Gowan, M.J.; Storfer-Isser, A.; Carter, A.S. Persistence of Maternal Depressive Symptoms throughout the Early Years of Childhood. J. Women’s Health 2009, 18, 637–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giallo, R.; Bahreinian, S.; Brown, S.; Cooklin, A.; Kingston, D.; Kozyrskyj, A. Maternal depressive symptoms across early childhood and asthma in school children: Findings from a Longitudinal Australian Population Based Study. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0121459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Austin, M.P.; Kingston, D. Psychosocial assessment and depression screening in the perinatal period: Benefits, challenges and implementation. In JoInt. Care of Parents and Infants in Perinatal Psychiatry; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 167–195. [Google Scholar]

- Woolhouse, H.; Brown, S.; Krastev, A.; Perlen, S.; Gunn, J. Seeking help for anxiety and depression after childbirth: Results of the Maternal Health Study. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2009, 12, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Austin, M.P.; Frilingos, M.; Lumley, J.; Hadzi-Pavlovic, D.; Roncolato, W.; Acland, S.; Saint, K.; Segal, N.; Parker, G. Brief antenatal cognitive behaviour therapy group intervention for the prevention of postnatal depression and anxiety: A randomised controlled trial. J. Affect. Disord. 2008, 105, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuijpers, P.; Geraedts, A.S.; van Oppen, P.; Andersson, G.; Markowitz, J.C.; van Straten, A. Interpersonal psychotherapy for depression: A meta-analysis. Am. J. Psychiatry 2011, 168, 581–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donker, T.; Bennett, K.; Bennett, A.; Mackinnon, A.; van Straten, A.; Cuijpers, P.; Christensen, H.; Griffiths, K.M. Internet-delivered interpersonal psychotherapy versus internet-delivered cognitive behavioral therapy for adults with depressive symptoms: Randomized controlled noninferiority trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2013, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stangier, U.; Schramm, E.; Heidenreich, T.; Berger, M.; Clark, D.M. Cognitive therapy vs interpersonal psychotherapy in social anxiety disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2011, 68, 692–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinelli, M.G. Interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed antepartum women: A pilot study. Am. J. Psychiatry 1997, 154, 1028–1030. [Google Scholar]

- Spinelli, M.G.; Endicott, J. Controlled clinical trial of interpersonal psychotherapy versus parenting education program for depressed pregnant women. Am. J. Psychiatry 2003, 160, 555–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandon, A.R.; Ceccotti, N.; Hynan, L.S.; Shivakumar, G.; Johnson, N.; Jarrett, R.B. Proof of concept: Partner-Assisted Interpersonal Psychotherapy for perinatal depression. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2012, 15, 469–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuart, S.; O’Hara, M.W. Interpersonal psychotherapy for postpartum depression: A treatment program. J. Psychother. Pr. Res. 1995, 4, 18–29. [Google Scholar]

- Stuart, S. Interpersonal psychotherapy for postpartum depression. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2012, 19, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stuart, S.; Clark, E. The treatment of postpartum depression with interpersonal psychotherapy and interpersonal counseling. Sante Ment. Que. 2008, 33, 87–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stuart, S.; Robertson, M. Interpersonal Psychotherapy 2E A Clinician’s Guide; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster, C.A.; Gold, K.J.; Flynn, H.A.; Yoo, H.; Marcus, S.M.; Davis, M.M. Risk factors for depressive symptoms during pregnancy: A systematic review. Am. J. Obs. Gynecol. 2010, 202, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pilkington, P.D.; Rominov, H.; Milne, L.C.; Giallo, R.; Whelan, T.A. Partners to Parents: Development of an online intervention for enhancing partner support and preventing perinatal depression and anxiety. Adv. Ment. Health 2017, 15, 42–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuart, S. What is IPT? The basic principles and the inevitability of change. J. Contemp. Psychother. 2008, 38, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutrona, C.E.; Russell, D.W. Autonomy promotion, responsiveness, and emotion regulation promote effective social support in times of stress. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2017, 13, 126–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzer, R.; Knoll, N. Functional roles of social support within the stress and coping process: A theoretical and empirical overview. Int. J. Psychol. 2007, 42, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurullah, A.S. Received and provided social support: A review of current evidence and future directions. Am. J. Health Stud. 2012, 27, 173–188. [Google Scholar]

- Champion, L. Social relationships and social roles. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2012, 19, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; McKay, G. Social support, stress and the buffering hypothesis: A theoretical analysis. Handb. Psychol. Health 1984, 4, 253–267. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, S.; Wills, T.A. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol. Bull. 1985, 98, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koszycki, D.; Bisserbe, J.-C.; Blier, P.; Bradwejn, J.; Markowitz, J. Interpersonal psychotherapy versus brief supportive therapy for depressed infertile women: First pilot randomized controlled trial. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2012, 15, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodman, J.H. Women’s attitudes, preferences, and perceived barriers to treatment for perinatal depression. Birth 2009, 36, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kingston, D.; Biringer, A.; McDonald, S.W.; Heaman, M.I.; Lasiuk, G.C.; Hegadoren, K.M.; McDonald, S.D.; van Zanten, S.V.; Sword, W.; Kingston, J.J.; et al. Preferences for Mental Health Screening Among Pregnant Women: A Cross-Sectional Study. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2015, 49, e35–e43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodman, J.H.; Tyer-Viola, L. Detection, treatment, and referral of perinatal depression and anxiety by obstetrical providers. J. Women’s Health 2010, 19, 477–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kingston, D.; Austin, M.P.; Heaman, M.; McDonald, S.; Lasiuk, G.; Sword, W.; Giallo, R.; Hegadoren, K.; Vermeyden, L.; van Zanten, S.V.; et al. Barriers and facilitators of mental health screening in pregnancy. J. Affect. Disord. 2015, 186, 350–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, K.M.; Farrer, L.; Christensen, H. The efficacy of internet interventions for depression and anxiety disorders: A review of randomised controlled trials. Med. J. Aust. 2010, 192, S4–S11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sockol, L.E. A systematic review and meta-analysis of interpersonal psychotherapy for perinatal women. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 232, 316–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Shamseer, L.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A.; Group, P.-P. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bright, K.S.; Charrois, E.M.; Mughal, M.K.; Wajid, A.; McNeil, D.; Stuart, S.; Hayden, K.A.; Kingston, D. Interpersonal psychotherapy for perinatal women: A systematic review and meta-analysis protocol. Syst. Rev. 2019, 8, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhat, A.; Grote, N.K.; Russo, J.; Lohr, M.J.; Jung, H.; Rouse, C.E. Collaborative care for perinatal depression among socioeconomically disadvantaged women: Adverse neonatal birth events and treatment response. Psychiatr. Serv. 2017, 68, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowen, A.; Baetz, M.; Schwartz, L.; Balbuena, L.; Muhajarine, N. Antenatal group therapy improves worry and depression symptoms. Isr. J. Psychiatry Relat. Sci. 2014, 51, 226–231. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H. Addressing maternal mental health needs in Singapore. Psychiatr Serv. 2011, 62, 102–103. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, J.P. Interpersonal Psychotherapy for Postnatal Anxiety Disorder. East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2015, 25, 88–94. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, R.; Tluczek, A.; Wenzel, A. Psychotherapy for postpartum depression: A preliminary report. Am J. Orthopsychiatry 2003, 73, 441–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crockett, K.; Zlotnick, C.; Davis, M.; Payne, N.; Washington, R. A depression preventive intervention for rural low-income African-American pregnant women at risk for postpartum depression. Archives Women’s Mental Health 2008, 11, 5–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deans, C.; Reay, R.; Buist, A. Addressing the mother–baby relationship in interpersonal psychotherapy for depression: An overview and case study. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 2016, 34, 483–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, C.L.; Grigoriadis, S.; Zupancic, J.; Kiss, A.; Ravitz, P. Telephone-based nurse-delivered interpersonal psychotherapy for postpartum depression: Nationwide randomised controlled trial. Br. J. Psychiatry 2020, 216, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, T.; Deeds, O.; Diego, M.; Hernandez-Reif, M.; Gauler, A.; Sullivan, S. Benefits of combining massage therapy with group interpersonal psychotherapy in prenatally depressed women. J. Bodyw. Mov Ther. 2009, 13, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, T.; Diego, M.; Delgado, J.; Medina, L. Peer support and interpersonal psychotherapy groups experienced decreased prenatal depression, anxiety and cortisol. Early Hum. Dev. 2013, 89, 621–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forman, D.R.; O’hara, M.W.; Stuart, S.; Gorman, L.L.; Larsen, K.E.; Coy, K.C. Effective treatment for postpartum depression is not sufficient to improve the developing mother–child relationship. Dev. Psychopathol. 2007, 19, 585–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, L.L.; Chan, S.W.-C.; Li, X.; Chen, S.; Hao, Y. Evaluation of an interpersonal-psychotherapy-oriented childbirth education programme for Chinese first-time childbearing women: A randomised controlled trial. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2010, 47, 1208–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, L.L.; Chan, S.W.; Sun, K. Effects of an interpersonal-psychotherapy-oriented childbirth education programme for Chinese first-time childbearing women at 3-month follow up: Randomised controlled trial. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2012, 49, 274–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, L.L.; Luo, S.Y.; Chan, S.W. Interpersonal psychotherapy-oriented program for Chinese pregnant women: Delivery, content, and personal impact. Nurs. Health Sci. 2012, 14, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.L.; Sun, K.; Chan, S.W. Social support and parenting self-efficacy among Chinese women in the perinatal period. Midwifery 2014, 30, 532–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.L.; Xie, W.; Yang, X.; Chan, S.W. Effects of an interpersonal-psychotherapy-oriented postnatal programme for Chinese first-time mothers: A randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2015, 52, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grote, N.K.; Bledsoe, S.E.; Swartz, H.A.; Frank, E. Feasibility of providing culturally relevant, brief interpersonal psychotherapy for antenatal depression in an obstetrics clinic: A pilot study. Res. Soc. Work Pract. 2004, 14, 397–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grote, N.K.; Swartz, H.A.; Geibel, S.L.; Zuckoff, A.; Houck, P.R.; Frank, E. A randomized controlled trial of culturally relevant, brief interpersonal psychotherapy for perinatal depression. Psychiatr Serv. 2009, 60, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grote, N.K.; Katon, W.J.; Russo, J.E.; Lohr, M.J.; Curran, M.; Galvin, E. Collaborative Care for Perinatal Depression in Socioeconomically Disadvantaged Women: A Randomized Trial. Depress Anxiety 2015, 32, 821–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grote, N.K.; Simon, G.E.; Russo, J.; Lohr, M.J.; Carson, K.; Katon, W. Incremental benefit-cost of MOMcare: Collaborative care for perinatal depression among economically disadvantaged women. Psychiatr Serv. 2017, 68, 1164–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajiheidari, M.; Sharifi, M.; Khorvash, F. The effect of interpersonal psychotherapy on marriage adaptive and postpartum depression in isfahan. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2013, 4, 256–261. [Google Scholar]

- Kao, J.C.; Johnson, J.E.; Todorova, R.; Zlotnick, C. The Positive Effect of a Group Intervention to Reduce Postpartum Depression on Breastfeeding Outcomes in Low-Income Women. Int. J. Group Psychother. 2015, 65, 445–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klier, C.M.; Muzik, M.; Rosenblum, K.L.; Lenz, G. Interpersonal psychotherapy adapted for the group setting in the treatment of postpartum depression. J. Psychother Pract Res. 2001, 10, 124–131. [Google Scholar]

- Kozinszky, Z.; Dudas, R.B.; Devosa, I.; Csatordai, S.; Tóth, É.; Szabó, D. Can a brief antepartum preventive group intervention help reduce postpartum depressive symptomatology? Psychother. Psychosom. 2012, 81, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenze, S.N.; Rodgers, J.; Luby, J. A pilot, exploratory report on dyadic interpersonal psychotherapy for perinatal depression. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2015, 18, 485–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenze, S.N.; Potts, M.A. Brief Interpersonal Psychotherapy for depression during pregnancy in a low-income population: A randomized controlled trial. J. Affect Disord. 2017, 165, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, S.S.; Lam, T.H. Group antenatal intervention to reduce perinatal stress and depressive symptoms related to intergenerational conflicts: A randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2012, 49, 1391–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moel, J.E.; Buttner, M.M.; O’Hara, M.W.; Stuart, S.; Gorman, L. Sexual function in the postpartum period: Effects of maternal depression and interpersonal psychotherapy treatment. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2010, 13, 495–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulcahy, R.; Reay, R.E.; Wilkinson, R.B.; Owen, C. A randomised control trial for the effectiveness of group Interpersonal Psychotherapy for postnatal depression. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2010, 13, 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nylen, K.J.; O’Hara, M.W.; Brock, R.; Moel, J.; Gorman, L.; Stuart, S. Predictors of the longitudinal course of postpartum depression following interpersonal psychotherapy. J. Consult Clin Psychol. 2010, 78, 757–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Hara, M.W.; Stuart, S.; Gorman, L.L.; Wenzel, A. Efficacy of interpersonal psychotherapy for postpartum depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000, 57, 1039–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Hara, M.W.; Pearlstein, T.; Stuart, S.; Long, J.D.; Mills, J.A.; Zlotnick, C. A placebo controlled treatment trial of sertraline and interpersonal psychotherapy for postpartum depression. J. Affect Disord. 2019, 245, 524–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearlstein, T.B.; Zlotnick, C.; Battle, C.L.; Stuart, S.; O’Hara, M.W.; Price, A.B. Patient choice of treatment for postpartum depression: A pilot study. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2006, 9, 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Posmontier, B.; Neugebauer, R.; Stuart, S.; Chittams, J.; Shaughnessy, R. Telephone-Administered Interpersonal Psychotherapy by Nurse-Midwives for Postpartum Depression. J. Midwifery Womens Health. 2016, 61, 456–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Posmontier, B.; Bina, R.; Glasser, S.; Cinamon, T.; Styr, B.; Sammarco, T. Incorporating interpersonal psychotherapy for postpartum depression into social work practice in Israel. Res. Soc. Work Pract. 2019, 29, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reay, R.; Fisher, Y.; Robertson, M.; Adams, E.; Owen, C. Group interpersonal psychotherapy for postnatal depression: A pilot study. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2006, 9, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinelli, M.G.; Endicott, J.; Leon, A.C.; Goetz, R.R.; Kalish, R.B.; Brustman, L.E. A controlled clinical treatment trial of interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed pregnant women at 3 New York City sites. J. Clin Psychiatry 2013, 74, 393–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinelli, M.G.; Endicott, J.; Goetz, R.R. Increased breastfeeding rates in black women after a treatment intervention. Breastfeed Med. 2013, 8, 479–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zlotnick, C.; Johnson, S.L.; Miller, I.W.; Pearlstein, T.; Howard, M. Postpartum depression in women receiving public assistance: Pilot study of an interpersonal-therapy-oriented group intervention. Am. J. Psychiatry 2001, 158, 638–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zlotnick, C.; Miller, I.W.; Pearlstein, T.; Howard, M.; Sweeney, P. A preventive intervention for pregnant women on public assistance at risk for postpartum depression. Am. J. Psychiatry 2006, 163, 1443–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zlotnick, C.; Capezza, N.M.; Parker, D. An interpersonally based intervention for low-income pregnant women with intimate partner violence: A pilot study. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2011, 14, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zlotnick, C.; Tzilos, G.; Miller, I.; Seifer, R.; Stout, R. Randomized controlled trial to prevent postpartum depression in mothers on public assistance. J. Affect Disord. 2016, 189, 263–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, H.; Ciliska, D.; Dobbins, M. Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies; Effective Public Health Practice Project; McMaster University: Toronto, OT, Canada, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Brunton, R.J.; Dryer, R.; Saliba, A.; Kohlhoff, J. Pregnancy anxiety: A systematic review of current scales. J. Affect. Disord. 2015, 176, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mughal, M.K.; Giallo, R.; Arnold, P.D.; Kehler, H.; Bright, K.; Benzies, K.; Wajid, A.; Kingston, D. Trajectories of maternal distress and risk of child developmental delays: Findings from the All Our Families (AOF) pregnancy cohort. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 248, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, T. Prenatal anxiety effects: A review. Infant Behav. Dev. 2017, 49, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bright, K.; Becker, G. Maternal emotional health before and after birth matters. In Late Preterm Infants; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 17–36. [Google Scholar]

- Egan, S.J.; Kane, R.T.; Winton, K.; Eliot, C.; McEvoy, P.M. A longitudinal investigation of perfectionism and repetitive negative thinking in perinatal depression. Behav. Res. 2017, 97, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowndes, T.A.; Egan, S.J.; McEvoy, P.M. Efficacy of brief guided self-help cognitive behavioral treatment for perfectionism in reducing perinatal depression and anxiety: A randomized controlled trial. Cogn. Behav. 2019, 48, 106–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standeven, L.R.; Nestadt, G.; Samuels, J. Genetics of perinatal obsessive–compulsive disorder: A focus on past genetic studies to inform future inquiry. In Biomarkers of Postpartum Psychiatric Disorders; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 95–109. [Google Scholar]

- Buchholz, J.L.; Hellberg, S.N.; Abramowitz, J.S. Phenomenology of perinatal obsessive–compulsive disorder. In Biomarkers of Postpartum Psychiatric Disorders; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 79–93. [Google Scholar]

- Marmarosh, C.; Holtz, A.; Schottenbauer, M. Group Cohesiveness, Group-Derived Collective Self-Esteem, Group-Derived Hope, and the Well-Being of Group Therapy Members. Group Dyn. 2005, 9, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuijpers, P.; Donker, T.; Weissman, M.M.; Ravitz, P.; Cristea, I.A. Interpersonal psychotherapy for mental health problems: A comprehensive meta-analysis. Am. J. Psychiatry 2016, 173, 680–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakobsen, J.C.; Hansen, J.L.; Simonsen, S.; Simonsen, E.; Gluud, C. Effects of cognitive therapy versus interpersonal psychotherapy in patients with major depressive disorder: A systematic review of randomized clinical trials with meta-analyses and trial sequential analyses. In Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE): Quality-assessed Reviews [Internet]; Centre for Reviews and Dissemination: Helingston, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cuijpers, P.; Van Straten, A.; Andersson, G.; Van Oppen, P. Psychotherapy for depression in adults: A meta-analysis of comparative outcome studies. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2008, 76, 909–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nillni, Y.I.; Mehralizade, A.; Mayer, L.; Milanovic, S. Treatment of depression, anxiety, and trauma-related disorders during the perinatal period: A systematic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2018, 66, 136–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Shea, G.; Spence, S.H.; Donovan, C.L. Group versus individual interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed adolescents. Behav. Cogn. Psychother. 2015, 43, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Sockol, L.E.; Epperson, C.N.; Barber, J.P. A meta-analysis of treatments for perinatal depression. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2011, 31, 839–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sockol, L.E.; Epperson, C.N.; Barber, J.P. Preventing postpartum depression: A meta-analytic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2013, 33, 1205–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, J.H.; Santangelo, G. Group treatment for postpartum depression: A systematic review. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2011, 14, 277–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misri, S.; Reebye, P.; Corral, M.; Milis, L. The use of paroxetine and cognitive-behavioral therapy in postpartum depression and anxiety: A randomized controlled trial. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2004, 65, 1236–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milgrom, J.; Negri, L.M.; Gemmill, A.W.; McNeil, M.; Martin, P.R. A randomized controlled trial of psychological interventions for postnatal depression. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2005, 44, 529–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Number (N) | Country | Trial Type (OT, RCT, QRT) | Study Type (Prevention or Treatment) | Comparison Type (Active, Treatment as Usual, Waitlist Control) | Comparison Treatment | Sample Population (Community, Clinical, Mixed, Prenatal, Postpartum) | Inclusion Type (Clinical Diagnosis, Self-Reported, Selected/Indicated, Universal) | Effectiveness of Treatment on Psychological Wellbeing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bhat et al. (2017) [44] | 160 | USA | RCT | Treatment | Treatment as usual | Treatment as usual (Maternity support services (MSS) Plus) | Community, Prenatal | Selected/Indicated | Yes—depressive symptoms |

| Bowen, Baetz, Schwartz, Balbuena, and Muhajarine (2014) [45] | 106 | Canada | QRT | Prevention | Active | Mindfulness-Based Therapy (MBT) | Community, Prenatal | Universal | Yes—depressive symptoms and stress |

| Brandon et al. (2012) [21] | 11 | USA | OT | Treatment | Clinical, Mixed Prenatal and Postpartum | Clinical diagnosis | Yes—depressive symptoms | ||

| Chen (2011) [46] | 176 | Singapore | QRT | Treatment | Active | Psychological, occupational, and/or medical social worker community resources program | Clinical, Postpartum | Self-reported | |

| Chung (2015) [47] | 1 | Hong Kong | Single Case Design | Treatment | Clinical, Postpartum | Clinical diagnosis | Yes—depression and anxiety symptoms | ||

| Clark, Tluczek, and Wenzel (2003) [48] | 66 | USA | QRT | Treatment | Active, Waitlist Control | Mother-Infant Therapy Group (MIT-G), Waitlist Control Group (WLC) | Clinical, Postpartum | Universal | Yes—depressive symptoms and stress |

| Crockett, Zlotnick, Davis, Payne, and Washington (2008) [49] | 36 | USA | RCT | Prevention | Treatment as usual | Standard Antenatal Care | Community, Prenatal | Selected/Indicated | |

| Deans, Reay, and Buist (2016) [50] | 1 | AUS | Single Case Design | Treatment | Community, Postpartum | Clinical diagnosis | |||

| Dennis, Grigoriadis, Zupancic, Kiss, and Ravitz (2020) [51] | 241 | Canada | RCT | Treatment | Treatment as usual | Treatment as usual (Standard postpartum depression services) | Community, Postpartum | Selected/Indicated | |

| Field et al. (2009) [52] | 112 | USA | QRT | Treatment | Active | Group Interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) and Group IPT and Massage Therapy | Community, Prenatal | Clinical diagnosis | Yes—depression, anxiety, and stress |

| Field, Diego, Delgado, and Medina (2013) [53] | 44 | USA | RCT | Treatment | Active | Peer support versus group IPT | Community Prenatal | Clinical diagnosis | Yes—depression, anxiety, and stress |

| Forman et al. (2007) [54] | 176 | USA | RCT | Treatment | Waitlist Control (depressed mothers) and Comparison Group (non-depressed mothers) | Waitlist control (WLC) and Control group (CG) (videotaped tasks to measure infant emotionality and parenting), Waitlist control (IPT for 12 weeks started after IPT group received their 12 weeks of IPT) | Community, Postpartum | Clinical diagnosis | Yes—depressive symptoms |

| L. L. Gao, Chan, Li, Chen, & Hao (2010) [55] | 194 | China | RCT | Prevention | Active | Childbirth education program only (routine antenatal education, consisting of 2 × 90-min sessions conducted by midwives, content: delivery process and childcare) | Community, Prenatal | Universal | Yes—depressive symptoms |

| L. L. Gao, Chan, & Sun, 2012 [56] | 194 | China | RCT | Prevention | Active | Childbirth education program only (routine antenatal education, consisting of 2 × 90-min sessions conducted by midwives, content: delivery process and childcare) | Community, Prenatal | Universal | Yes—depressive symptoms |

| L. L. Gao, Luo, and Chan (2012) [57] | 83 | China | OT | Prevention | Community, Postpartum | Universal | |||

| L. L. Gao, Sun, and Chan (2014) [58] | 68 | China | QRT | Prevention | Active | Childbirth education program only (routine antenatal education, consisting of 2 × 90-min sessions conducted by midwives, content: delivery process and childcare) | Community, Prenatal | Universal | |

| L. L. Gao, Xie, Yang, and Chan (2015) [59] | 180 | China | RCT | Prevention | Treatment as usual | Treatment as usual (TAU) (pamphlet on sources of assistance after discharge) | Community, Postpartum | Universal | Yes—depressive symptoms |

| Grote, Bledsoe, Swartz, and Frank (2004) [60] | 12 | USA | OT | Treatment | Community, Prenatal (pregnant, depressed, socioeconomically disadvantaged) | Self-reported | Yes—depression and anxiety symptoms | ||

| Grote et al. (2009) [61] | 53 | USA | RCT | Treatment | Treatment as usual | Enhanced Usual Care | Community, Prenatal (pregnant, depressed, socioeconomically disadvantaged) | Self-reported | Yes—depressive symptoms |

| Grote et al. (2015) [62] | 164 | USA | RCT | Treatment | Active | Intensive Maternity Support Services (MSS-Plus) | Community, Prenatal (pregnant, depressed, socioeconomically disadvantaged) | Self-reported | Yes—depression and anxiety symptoms |

| Grote et al. (2017) [63] | 164 | USA | RCT | Treatment | Active | Intensive Maternity Support Services (MSS-Plus) | Community, Prenatal (pregnant, depressed, socioeconomically disadvantaged) | Self-reported | Yes—depressive symptoms |

| Hajiheidari, Sharifi, and Khorvash (2013) [64] | 34 | Iran | QRT | Treatment | Treatment as usual | Referred to Mental health providers | Community, Postpartum | Clinical diagnosis | Yes—depressive symptoms |

| Kao, Johnson, Todorova, and Zlotnick (2015) [65] | 99 | USA | RCT | Treatment | Treatment as usual | Treatment as usual (TAU) (Standard care—optional classes on breastfeeding, infant safety, and parenting—no depression assessments or mental health groups) | Community, Prenatal | Selected/Indicated | |

| Klier, Muzik, Rosenblum, and Lenz (2001) [66] | 17 | Austria | OT | Treatment | Clinical, Postpartum | Clinical diagnosis | Yes—depressive symptoms | ||

| Kozinszky, Dudas, Devosa, Csatordai, Tóth, et al. (2012) [67] | 1719 | Hungary | RCT | Prevention | Treatment as usual | Treatment as usual (TAU) (4 group meetings: education on pregnancy, childbirth, and baby care) | Community, Prenatal | Universal | Yes—depressive symptoms |

| Lenze, Rodgers, and Luby (2015) [68] | 9 | USA | OT | Treatment | Community, Prenatal | Clinical diagnosis | Yes—depressive symptoms | ||

| Lenze and Potts (2017) [69] | 42 | USA | RCT | Treatment | Treatment as usual | Treatment as usual (TAU) (Enhanced Treatment as Usual) | Community, Prenatal | Clinical diagnosis | Yes—depressive and anxiety symptoms |

| Leung and Lam (2012) [70] | 156 | Hong Kong | RCT | Prevention | Treatment as usual | Routine antenatal care from MCHC (physical exam and brief individual interview) | Community, Prenatal | Universal | Yes—stress |

| Moel, Buttner, O’Hara, Stuart, and Gorman (2010) [71] | 176 | USA | RCT | Treatment | Waitlist control and Treatment as usual | Treatment as usual (TAU) (no depression, no intervention), Waitlist control (no intervention during 12 week wait, then received 12-week IPT) | Community, Postpartum | Selected/Indicated | Yes—depressive symptoms |

| Mulcahy, Reay, Wilkinson, and Owen (2010) [72] | 57 | Australia | RCT | Treatment | Treatment as usual | Encompassed all options for postnatal depression that were available to women in the Australian Capital Territory (ACT) community, such as antidepressant, natural remedies, nondirective counselling, maternal and child health nurse support, community support groups, individual psychotherapy or group therapy already provided in the community (either publicly or privately) | Clinical, Postpartum | Clinical diagnosis | Yes—depressive symptoms |

| Nylen et al. (2010) [73] | 120 | USA | QRT | Treatment | Waitlist control | Waitlist control (WLC) (after 12 week waiting period, Waitlist control received 12 IPT sessions) | Community, Postpartum | Selected/Indicated | Yes—depressive symptoms |

| O’Hara, Stuart, Gorman, and Wenzel (2000) [74] | 120 | USA | QRT | Treatment | Waitlist control | Waitlist control (WLC) (after 12 week waiting period, Waitlist control received 12 IPT sessions) | Clinical, Postpartum | Clinical diagnosis | Yes—depressive symptoms |

| O’Hara et al. (2019) [75] | 53 | USA | RCT | Treatment | Active | IPT (n = 56), Sertraline (n = 56), clinical management and pill placebo (n = 53) | Clinical, Postpartum | Clinical diagnosis | |

| Pearlstein et al. (2006) [76] | 23 | USA | QRT | Treatment | Active | Sertraline (n = 2), Sertraline and IPT (n = 10)—Sertraline component: 8 sessions over 12 weeks | Clinical, Postpartum | Clinical diagnosis | Yes—depressive symptoms |

| Posmontier, Neugebauer, Stuart, Chittams, and Shaughnessy (2016) [77] | 61 | USA | QRT | Treatment | Active | Referral to a variety of Mental Health Practitioner (MHP) who provided various psychotherapeutic modalities such as supportive and psychodynamic psychotherapy | Clinical, Postpartum | Clinical diagnosis | Yes—depressive symptoms |

| Posmontier et al. (2019) [78] | 27 | Israel | OT | Treatment | Active | Includes a variety of cognitive-behavioral, psychodynamic, psychoeducational, and/or non-specific supportive modalities, varying number, and duration of sessions | Clinical, Postpartum | Clinical diagnosis | Yes—depressive symptoms |

| Reay et al. (2006) [79] | 18 | Australia | OT | Treatment | Community, Postpartum | Selected/Indicated | Yes—depressive symptoms | ||

| M. G. Spinelli (1997) [19] | 13 | USA | OT | Treatment | Clinical, Prenatal | Clinical diagnosis | Yes—depressive symptoms | ||

| Spinelli and Endicott (2003) [20] | 50 | USA | RCT | Treatment | Active | Parenting Education Program for Unipolar Depressed Nonpsychotic pregnant women (therapist-led weekly 45 min sessions for 16 weeks) | Mixed Clinical and Community, Prenatal | Clinical diagnosis | Yes—depressive symptoms |

| Spinelli, Endicott, Leon, et al. (2013) [80] | 142 | USA | RCT | Treatment | Active | Parent Education Program (therapist-led 45 min weekly didactic lectures on pregnancy, postpartum, breastfeeding education—provided to 100% participants, and early infant development) | Mixed Clinical and Community, Prenatal | Clinical diagnosis | Yes—depressive symptoms |

| Spinelli, Endicott, and Goetz (2013) [81] | 142 | USA | RCT | Treatment | Active | Parent Education Program (therapist-led 45 min weekly didactic lectures for 12 weeks) | Mixed Clinical and Community, Prenatal | Clinical diagnosis | |

| Zlotnick, Johnson, Miller, Pearlstein, and Howard (2001) [82] | 37 | USA | RCT | Prevention | Treatment as Usual | Treatment as usual—standard medical attention and treatment provided to all attending prenatal clinic | Community, Prenatal | Selected/Indicated | |

| Zlotnick, Miller, Pearlstein, Howard, and Sweeney (2006) [83] | 99 | USA | RCT | Prevention | Treatment as Usual | Standard Antenatal Care | Community, Prenatal | Selected/Indicated | |

| Zlotnick, Capezza, and Parker (2011) [84] | 54 | USA | RCT | Treatment | Treatment as Usual | Treatment as usual—(standard medical attention and treatment provided to all attending prenatal clinic and educational material/listing of resources for IPV) | Community, Prenatal | Selected/Indicated | |

| Zlotnick, Tzilos, Miller, Seifer, and Stout (2016) [85] | 205 | USA | RCT | Prevention | Treatment as Usual | Standard Antenatal Care | Community, Prenatal | Selected/Indicated |

| Study | Timing (Prenatal or Postpartum) | Timing in Weeks Pregnant or Postpartum | Intervention | Comments | Methods of Administration (Individual, Partners, Groups) | Mode of Administration | Setting (Clinical or Community) | Included Partner | # of Sessions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bhat et al. (2017) [44] | PN | MSS-Plus from pregnancy to 2 months PP; MOMCare from pregnancy to 12 months PP | Pretherapy engagement brief IPT, Pharmacotherapy or both (MOMCare) | Individual | Combination Face-to-face Telephone | Community | No | Not specified | |

| Bowen et al. (2014) [45] | PN | 15–25 weeks pregnant | IPT | 6 weeks duration | Group | Face-to-face | Community | No | 5 group sessions (3 groups were Mindfulness Based (MFB), 2 groups were IPT) |

| Brandon et al. (2012) [21] | PN | From 12 weeks prenatal to 12 weeks postpartum | 1st phase—Partner assisted IPT (both partners involved, assessed depressive experience, identify and understand the triggers of depressive symptoms), 2nd phase—Role expectations (self/and partner) and quality of their interactions, 3rd phase—consolidate change, explore sources of support, and process the experience of therapy | Emotional Focused Couples Therapy (EFCT) informed—Partner-Assisted IPT | Partners | Face-to-face | Clinical | Yes | 8 session to be completed within a 12-week period |

| Chen (2011) [46] | PP | 2 weeks to 6 months postpartum | Principles of IPT and CBT | Individual, offered group support | Combination Face-to-face, telephone (high scorers who refused psychiatric intervention) | Clinical | No | Unsure of number of sessions, duration of treatment between 3–6 months | |

| Chung (2015) [47] | PP | Unsure | IPT | Maintenance sessions—every 2 weeks for 20 min | Individual | Face-to-face | Clinical | No | 12 |

| Clark et al. (2003) [48] | PP | 4–96 weeks postpartum | IPT | Three groups—IPT (Individual), M-ITG (Group, includes elements of IPT/CBT), and WLC | Individual and Group | Face-to-face | Clinical | No | M-ITG and IPT sessions: 12 (weekly for 1 h) in addition to a 1.5-h initial intake; WLC: waiting to receive M-ITG |

| Crockett et al. (2008) [49] | PN | 24–31 weeks pregnant | ROSE Program (Reach Out, Stand Strong: Essentials for New Moms)—IPT based | Group (and Individual booster) | Face-to-face | Community (group sessions), Participant’s home (booster session) | No | 4 (1.5 h during pregnancy) group sessions weekly and 1 (50 min) individual booster 2 weeks after delivery | |

| Deans et al. (2016) [50] | PP | 7 months postpartum | IPT for the mother-child relationship | Was a group intervention—reporting on one individual in the group | Group and Individual | Face-to-face | Community | Yes—1 session with partner at the halfway point (between session 5 and 6) | 10 (in addition: two pre-group individual sessions and one psychoeducation partner session at the halfway point) |

| Dennis et al. (2020) [51] | PP | Between 2 and 24 weeks postpartum | IPT | Individual | Telephone | Community | No | 12 weekly 60-min telephone IPT sessions | |

| Field et al. (2009) [52] | PN | 22–28 weeks pregnant | IPT and IPT with Massage | Group | Face-to-face | Community | No | Group IPT—1 hr per week for 6 weeks, IPT and Massage—1 hr IPT per week for 6 weeks, 20-min massage once a week for 6 weeks | |

| Field et al. (2013) [53] | PN | 22–34 weeks pregnant | Group IPT | Group | Face-to-face | Community | No | IPT Group: 1 h per week for 12 weeks, Peer Support Group: 20 min/week for 12 weeks | |

| Forman et al. (2007) [54] | PP | 6 months postpartum | IPT with mothers and their babies | Mother-infant | Face-to-face | Community | No | 12 weeks of IPT | |

| L. L. Gao et al., 2010 [55] | PN | over 28 weeks pregnant | Routine antenatal education & IPT-oriented childbirth education program | Small groups of no more than 10 people | Groups, Telephone | Combination Face-to-face (group) and one telephone follow-up call in the postpartum period (2 weeks) | Community | No | Intervention group received routine antenatal education [2 × 90-min sessions conducted by midwives, content: delivery process and childcare] & IPT-oriented childbirth psychoeducation program [Two 2-hr group sessions with one telephone follow-up in the postpartum period] |

| L. L. Gao et al. (2012) [56] | PN | over 28 weeks pregnant | Routine childbirth education program & IPT-oriented childbirth education program | Small groups of no more than 10 people | Groups, Telephone | Combination Face-to-face (group) and one telephone follow-up call in the postpartum period (2 weeks) | Community | No | Intervention group received routine antenatal education [2 × 90 min sessions conducted by midwives, content: delivery process and childcare] & IPT-oriented childbirth psychoeducation program [Two 90 min antenatal group sessions with one telephone follow up within 2 weeks after delivery] |

| L. L. Gao et al. (2012) [57] | PN | over 28 weeks pregnant | Routine antenatal childbirth education & IPT-oriented childbirth psychoeducation program | Small groups of no more than 10 people | Groups, Telephone | Combination Face-to-face, telephone | Community | No | Routine childbirth education classes (2–90-min sessions) & IPT-oriented childbirth psychoeducation program (Two 90 min antenatal group sessions with one telephone follow up within 2 weeks after delivery) |

| L. L. Gao et al. (2014) [58] | PN | over 28 weeks pregnant | Routine childbirth education program & IPT-oriented childbirth education program | Groups, Telephone | Combination Face-to-face (group) and one telephone follow-up call in the postpartum period (2 weeks) | Community | No | Intervention group received routine antenatal education [2 × 90 min sessions conducted by midwives, content: delivery process and childcare] & IPT-oriented childbirth psychoeducation program [Two 90 min antenatal group sessions with one telephone follow up within 2 weeks after delivery] | |

| L. L. Gao et al. (2015) [59] | PP | 2–3 days postpartum | Pamphlet on sources of assistance after discharge & IPT-oriented postnatal psychoeducation programme | Outcomes measured: Postpartum depressive symptoms, social support, and maternal role competence | Individual | Combination Face-to-face, telephone | Community | No | One 1-hr session (before hospital discharge) and a telephone follow-up within 2 weeks after discharge |

| Grote et al. (2004) [60] | PN | 12–28 weeks pregnant | IPT-B (brief) & IPT-M (maintenance) | 12 people who screened > 10 on the EPDS, IPT sessions scheduled as much as possible preceding or following their antenatal appt, depressed, low-income, minority women | Individual | Combination Face-to-face, telephone | Community | No | 9 sessions (no timeframe for each session) (Pre-treatment engagement interview, 8 IPT-B [Brief] sessions, IPT-M [maintenance] sessions monthly up to 6 months [max: 6 sessions] Postpartum) |

| Grote et al. (2009) [61] | PN | 10–32 weeks pregnant | IPT-B—multicomponent, enhanced, culturally relevant (reflected 7/8 components delineated in the culturally centered framework of Bernal and colleagues (1995)) | EPDS ≥ 12, ≥18 years old, English speaking, low income. Cultural sensitivity and Culturally relevant additions integrated into IPT-B (free bus passes, childcare, facilitate access to social services—food, job training, housing, free baby supplies) | Individual | Combination—Face-to-face, telephone | Community | No | Pre-treatment engagement interview, 8—Brief IPT sessions (in-person, telephone), and bi-weekly or monthly IPT maintenance for up to 6 months post-baseline, |

| Grote et al. (2015) [62] | PN | 12–32 weeks pregnant | MSS-Plus AND MOMCare—18 month collaborative care intervention stepped treatment approach (included initial pre-treatment engagement session, choice of IPT-B and/or pharmacotherapy, telephone plus in-person visits) | screened to include participants who had probable depression/dysthymia, | Individual | Combination Face-to-face, telephone (calls or texts) | Community (Public Health Centers, Patient’s home) | No | Pre-treatment engagement interview, 8—Brief IPT sessions every 1–2 weeks (in-person, telephone) across 3–6 months post-baseline, and monthly IPT maintenance for up to 18 months post-baseline, 60 min/session |

| Grote et al. (2017) [63] | PN | 12–32 weeks pregnant | MOMCare—18-month collaborative care intervention, stepped treatment approach—women with less than 50% improvement in depressive symptoms by 6–8 weeks received a revised treatment plan | screened for depression, Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) scoring ≥ 10, and screened for dysthymia: MINI | Individual | Combination—Face-to-face, telephone | Community (Public Health Centers, Patient’s home) | No | Pre-treatment engagement interview, 8—Brief IPT sessions every 1–2 weeks (in-person, telephone) across 3–4 months post-baseline, and monthly IPT maintenance for up to 18 months post-baseline, 60 min/session |

| Hajiheidari et al. (2013) [64] | PP | not specified | IPT—marriage | EPDS ≥ 14, and by the diagnosing review by a psychologist | Partners | Face-to-face | Community | Yes (scores not collected/analysed) | 10—sessions/10 weeks |

| Kao et al. (2015) [65] | PN | 20–35 weeks pregnant | IPT—Reach Out, Stand Strong, Essentials for new mothers (ROSE) & standard care | score of 27 or greater on a 17-item tool to assess PDD, low income | Group (3–5 people per group) | Face-to-face | Community (Groups at prenatal clinic, Booster at clinic or participant’s home) | No | 4 sessions/60 min/4 weeks and one 50-min booster after delivery |

| Klier et al. (2001) [66] | PP | 4–45 weeks postpartum | IPT | Combination (Individual and Group) | Face-to-face | Clinical | No | 12 sessions: Individual (two 60-min pre-sessions), Group (nine 90-min weekly group sessions), Individual (one 60-min termination session) | |

| Kozinszky, Dudas, Devosa, Csatordai, Tóth, et al. (2012) [67] | PN | 25–29 weeks pregnant | Psychoeducation and psychotherapy for PPD utilizing IPT and CBT elements—each session ended with relaxation exercises | Group (max 15 per group) | Face-to-face | Community | Yes—allowed to attend | 4 sessions—3-h—over 4 consecutive weeks | |

| Lenze et al. (2015) [68] | PN | 12–30 weeks pregnant | IPT-Dyad—two phases, antepartum phase based on brief, culturally relevant IPT developed by Grote 2008 (weekly sessions), postpartum phase (biweekly sessions then monthly) | Individual | Face-to-face | Community (Sessions offered at participant’s home, at the clinic, or at other convenient community location) | No | Antenatal—minimum dose 7 sessions—55% achieved minimum dose—sessions included an engagement session to explore views about depression, treatment, and barriers to care strategies of standard IPT. Postpartum—minimum dose of 8—71% achieved minimum dose—sessions were on maintaining interpersonal functioning, infant emotional development theory, and attachment theory | |

| Lenze and Potts (2017) [69] | PN | 12–30 weeks pregnant | Brief IPT engagement session and then 8 IPT sessions—those who completed all 9 sessions had access to maintenance sessions | Individual | Combination Face-to-face (participants had the option to receive brief-IPT over the phone) | Community (Sessions offered at participant’s home, at the research clinic, or at other convenient community location) | No | 1 engagement session, 8 IPT sessions as described by Grote et al. 2004 (length of time for sessions not included) | |

| Leung and Lam (2012) [70] | PN | 14–32 weeks pregnant | IPT-oriented intervention | Group | Face-to-face | Community | No | 4 weekly 1.5-h sessions/4 weeks | |

| Moel et al. (2010) [71] | PP | Postpartum—not sure of timing | IPT | Sample from O’Hara study 2000 | Individual | Face-to-face | Community (Therapist’s private practice clinics) | No | 12 h over 12 weeks |

| Mulcahy et al. (2010) [72] | PP | less than 12 months postpartum | IPT | 60% onset of current depression after the birth of the baby, 22% during pregnancy, 18% prior to conception | Combination (Individual, Group, partners) | Face-to-face | Clinical | Yes (evening session only) | 11 sessions in total (2 individual, 8 group, 1 evening group for men only—each 2 h/session) over 8 weeks |

| Nylen et al. (2010) [73] | PP | 6–24 months postpartum | IPT | Sample from O’Hara study 2000 | Individual | Face-to-face | Community | No | 12 h over 12 weeks (12—1-h sessions over 12 weeks) |

| O’Hara et al. (2000) [74] | PP | 6–9 months postpartum | IPT | This sample also used in the Nylen study | Individual | Face-to-face | Clinical | No | 12 h over 12 weeks |

| O’Hara et al. (2019) [75] | PP | within 6 months postpartum | IPT | Recruited from 2008 to 2013 | Individual | Face-to-face | Clinical | No | 12 individual 50-min sessions over 12 weeks |

| Pearlstein et al. (2006) [76] | PP | 6 months postpartum | IPT | 11 women picked IPT, 2 picked sertraline, and 10 picked sertraline and IPT | Individual | Face-to-face | Clinical (outpatient mental health setting) | No | IPT: 12–50-min sessions over 12 weeks, |

| Posmontier et al. (2016) [77] | PP | 6 weeks–6 months postpartum | CNM-IPT (Certified Nurse-Midwives Telephone Administered Interpersonal Psychotherapy) | Individual | Telephone | Clinical | No | 8 sessions lasting 50 min per session over a 12–week period | |

| Posmontier et al. (2019) [78] | PP | 1–6 months postpartum | IPT | Individual | Face-to-face | Clinical | No | Up to 8 × 50-min sessions | |

| Reay et al. (2006) [79] | PP | less than 12 months postpartum | IPT-G (Group) | Group (with individual, partners) | Face-to-face | Community (local community centers) | Yes | 2 individual sessions (pre-therapy, 6–week post-group appointment), 8 weekly group sessions at 2 h a session (delivered over 8 weeks), 2-h partners evening (midway through group sessions—weeks 3–7) | |

| M. G. Spinelli (1997) [19] | PN | 6–40 weeks pregnant | IPT for antenatal depression | Individual | Face-to-face | Clinical | No | 16 weekly sessions, 50 min per session | |

| Spinelli and Endicott (2003) [20] | PN | 6–36 weeks pregnant | IPT for antenatal depression—bilingual (Spanish and English) | lower socioeconomic 50 started—25 in each group—ended with 17 in control group and 21 in treatment group | Individual | Combination Face-to-face, telephone (as needed) | Clinical and Community | No | 16 weekly 45 min per session |

| Spinelli, Endicott, Leon, et al. (2013) [80] | PN | 12–33 weeks pregnant | IPT for antenatal depression (bilingual) (breastfeeding education provided to 83% participants even though not mandatory) | Same sample as the Spinelli et al. 2013b | Individual | Combination Face-to-face, telephone (as needed) | Clinical and Community | No | 12 weekly sessions—45 min per session |

| Spinelli, Endicott, and Goetz (2013) [81] | PN | 12–33 weeks pregnant | IPT for antenatal depression—bilingual (Spanish and English) | Individual | Combination Face-to-face, telephone (as needed), | Clinical and Community | No | 12 weekly sessions—5 min per session | |

| Zlotnick et al. (2001) [82] | PN | 12–32 weeks pregnant | IPT (Survival Skills for New Moms) | women receiving public assistance | Group | Face-to-face | Community | No | 4–60-min sessions over 4 weeks |

| Zlotnick et al. (2006) [83] | PN | 12–32 weeks pregnant | ROSE program IPT-based intervention & standard antenatal care | women receiving public assistance | Group (and Individual-booster) | Face-to-face | Community | No | four sessions 60 min group session over 4 weeks and a 50-min individual booster session after delivery |

| Zlotnick et al. (2011) [84] | PN | 12–32 weeks pregnant | IPT—for Depression and PTSD | women with intimate partner violence—low-income | Individual | Face-to-face | Community | No | 4–60-min sessions over 4 weeks, 1–60 min individual ‘booster’ session within 2 weeks of delivery |

| Zlotnick et al. (2016) [85] | PN | 20–35 weeks pregnant | ROSE program IPT-based intervention—group & standard antenatal care | women receiving public assistance | Group (and Individual-booster) | Face-to-face | Community | No | 4–90-min group sessions over a 4-week period, and a 50-min individual booster session 2 weeks after delivery |

| Study | Type (Prevention or Treatment Study) | Assessment of Depressive Symptoms | Prevalence of Depressive Episodes | Assessment of Symptoms of Anxiety | Stress | Attachment | Quality of Life | Relationship Satisfaction/Quality | Adjustment | Social Support | Others |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bhat et al. (2017) [44] | Treatment | SCL-20 | PHQ-9, MINI | PTSD-Checklist Civilian Version (PCL-C) | WSAS | WSAS | PES | ||||

| Bowen et al. (2014) | Prevention | EPDS | STAI | CWS | MSSS | Satisfaction with Psychotherapy group: 1. What did you find most positive about the group? 2. What would you change in the group? | |||||

| Brandon et al. (2012) [21] | Treatment | HAM-D EPDS, EPDS—Partner version | DSM-IV MDD, SCID-IV, HAM-D17 | DAS | DAS | ||||||

| Chen (2011) [46] | Treatment | EPDS | EPDS | GAF | |||||||

| Chung (2015) [47] | Treatment | EPDS, HAM-D | EPDS = 22 | HAM-A | |||||||

| Clark et al. (2003) [48] | Treatment | CES-D, BDI | DSM-IV MDD | PSI | PCERA | BSID | |||||

| Crockett et al. (2008) [49] | Prevention | EPDS | CSQ > 27, SCID-R | PSI | SAS-SR, PPAQ | ||||||

| Deans et al. (2016) [50] | Treatment | BDI | SCID-II, EPDS | BAI | PSI | MAI | Infant Characteristics Questionnaire, Emotional Availability Scales (EAS) | ||||

| Dennis et al. (2020) [51] | Treatment | EPDS > 12 eligible to be referred | SCID depression module. EPDS > 12. | STAI | ECR | DAS | Health service utilization and costs | ||||

| Field et al. (2009) [52] | Treatment | CES-D | SCID-I | STAI | Cortisol samples (saliva) | The relationship questionnaire | SSQ-R | STAXI | |||

| Field et al. (2013) [53] | Treatment | CES-D | SCID-I | STAI | Cortisol samples (saliva) | STAXI | |||||

| Forman et al. (2007) [54] | Treatment | IDD, HAM-D | IDD, SCID, HRSD | PSI | AQS | IBQ, CBQ, Maternal Responsiveness, Child Behaviour Problems—Child Behavior Checklist/2–3 | |||||

| L. L. Gao et al. (2010) [55] | Prevention | EPDS | EPDS ≥ 13 | Satisfaction with Interpersonal Relationships Scale | GHQ | ||||||

| L. L. Gao et al. (2012) [56] | Prevention | EPDS, GHQ | EPDS ≥ 13 | PSSS | PSOC—with Efficacy (PSOC-E). GHQ | ||||||

| L. L. Gao et al. (2012) [57] | Prevention | PSSS | Qualitative interviews—looking at close ended questions of the Program Satisfaction Questionnaires | ||||||||

| L. L. Gao et al. (2014) [58] | Prevention | PSSS | PSOC—with Efficacy (PSOC-E) | ||||||||

| L. L. Gao et al. (2015) [59] | Prevention | EPDS | EPDS ≥ 13 | PSSS | PSOC—with Efficacy (PSOC-E) | ||||||

| Grote et al. (2004) [60] | Treatment | EPDS, BDI, HAM-D | EPDS > 10, DIS | BAI | IIP | SAS, PPAQ | Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey | satisfaction with each social support, participants completed a 4-item treatment satisfaction survey and 5-point Likert scale on how positive they felt about their pregnancy (after each session) | |||

| Grote et al. (2009) [61] | Treatment | EPDS, BDI, SCID | EPDS ≥ 12 | BAI | SAS, PPAQ | CAGE-AID, MINI | |||||

| Grote et al. (2015) [62] | Treatment | Hopkins Symptom Checklist SCL-20 | PHQ-9 ≥ 10 and at least five symptoms scored as ≥2 with one cardinal symptom on the PHQ-9, plus a functional impairment to include participants with probable MDD, MINI-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) to include participants with probable dysthymia | PHQ | PCL-C | RQ | WSAS | CAGE-AID, MINI, childhood trauma—Childhood Trauma Questionnaire | |||

| Grote et al. (2017) [63] | Treatment | SCL-20 | PHQ-9, MINI | PHQ | PCL-C | CAGE-AID, MINI, SCL-20 (Depression-free Days (DFDs)), Costs for MOMCare intervention, CSI | |||||

| Hajiheidari et al. (2013) [64] | Treatment | EPDS, BDI-II | EPDS ≥ 14 (used for primary screening only) | Revised Double Adaptive Score (Marriage Adaptive) | EPDS ≥ 14 and by the diagnosing review by a psychologist | ||||||

| Kao et al. (2015) [65] | Treatment | Predictive Index of PPD, EPDS | Predictive Index of PPD—score of 27 or higher (high-risk status) | SAS | Breast feeding—initiation and duration | ||||||

| Klier et al. (2001) [66] | Treatment | HAM-D-21, EPDS | SCID-I, HAM-D-21 > 13. | DAS | DAS | Inventory of Interpersonal Problems (IIP) (German version), SCID-II used to diagnose Axis II disorders | |||||

| Kozinszky, Dudas, Devosa, Csatordai, Tóth, et al. (2012) [67] | Prevention | LQ ≥ 12 | Additional structured questions exploring sociodemographic, economic, and psychological risk factors | ||||||||

| Lenze et al. (2015) [68] | Treatment | EPDS | EPDS > 12, SCID—Axis I | PSI | SSQR | Infant-Toddler Social and Emotional Assessment, Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (acceptability) | |||||

| Lenze and Potts (2017) [69] | Treatment | EPDS | EPDS ≥ 10, SCID | Brief-STAI | ECR-R | SSQR | DLC, CSQ | ||||

| Leung and Lam (2012) [70] | Prevention | EPDS | EPDS < 12 | PSS | Relationship Efficacy Measure | perceived ability to cooperate in childcare, 4-item subjective happiness scale | |||||

| Moel et al. (2010) [71] | Treatment | SCID, BDI, HAM-D | IDD, SCID-I | DAS | DAS | LIFE-II | |||||

| Mulcahy et al. (2010) [72] | Treatment | HAM-D, EPDS, BDI | MCMI-III, HAM-D ≥ 14 | MAI | DAS | ISEL | |||||

| Nylen et al. (2010) [73] | Treatment | BDI, HAM-D | IDD, SCID, HAM-D scores ≥ 12 | LIFE-II | |||||||

| O’Hara et al. (2000) [74] | Treatment | SCID, HAM-D) (≥12), BDI | IDD, SCID | DAS | SAS-SR, PPAQ, DAS | HAM-D adding items on hypersomnia, hyperphagia and weight gain | |||||

| O’Hara et al. (2019) [75] | Treatment | BDI, EPDS, PHQ-9 replaced the EPDS | SCID, HAM-D ≥ 15 | Inventory of Depression and Anxiety Symptoms, General depression scale | PPAQ | Clinical Global Impressions-Severity of Illness and Improvement scales | |||||

| Pearlstein et al. (2006) [76] | Treatment | BDI, HAM-D, EPDS | SCID, BDI ≥25, HAM-D ≥ 14, EPDS | ||||||||

| Posmontier et al. (2016) [77] | Treatment | HAM-D, EPDS | EPDS > 9, MINI—met criteria for MDD | Mother-to-Infant Bonding Scale | DAS | SSQ | GAF, CSQ-8, MINI, IAQS | ||||

| Posmontier et al. (2019) [78] | Treatment | EPDS | EPDS score of 10–18 for inclusion | PPAQ | CSQ-8 | ||||||

| Reay et al. (2006) [79] | Treatment | HAM-D, EPDS, BDI | EPDS >13 | SAS | Patient Satisfaction Survey (developed for this study) | ||||||

| M. G. Spinelli (1997) [19] | Treatment | HAM-D, EPDS, BDI | SCID, HAM-D ≥ 12 | Serum thyroid function tests, Clinical Global Impression (global ratings of symptom severity and improvement) | |||||||

| Spinelli and Endicott (2003) [20] | Treatment | HAM-D, BDI, EPDS | SCID, HAM-D ≥ 12 | Maudsley Mother Infant Interaction Scale | Assessment of Mood Change (weekly), Clinical Global Impression (global ratings of symptom severity and improvement) | ||||||

| Spinelli, Endicott, Leon, et al. (2013) [80] | Treatment | HAM-D, EPDS | SCID, HAM-D ≥ 12 | Postpartum Bonding Questionnaire | Breastfeeding, SCID for DSM-IV to rule out comorbid diagnosis, Clinical Global Impression (global ratings of symptom severity and improvement) | ||||||

| Spinelli, Endicott, and Goetz (2013) [81] | Treatment | HAM-D, EPDS | SCID, HAM-D ≥ 12 | Maternal Fetal Attachment Scale | SCID for DSM-IV to rule out comorbid diagnosis, Clinical Global Impression (global ratings of symptom severity and improvement) | ||||||

| Zlotnick et al. (2001) [82] | Prevention | BDI | SCID | ||||||||

| Zlotnick et al. (2006) [83] | Prevention | BDI, LIFE | CSQ > 27 | Range of Impaired Functioning Tool | SCID for DSM-IV-NP Axis 1 to rule out comorbid diagnosis, | ||||||

| Zlotnick et al. (2011) [84] | Prevention | EPDS, PSR, LIFE | Revised Conflict Tactic Scale (CTS2)—assessed for IPV in last year for inclusion The Davidson Trauma Scale Criterion A from the PTSD module of the SCID-NP for DSM-IV—assessed for history of trauma, SCID-NP for DSM-IV Axis I—assessed for affective d/o, PTSD, SUD for exclusion | ||||||||

| Zlotnick et al. (2016) [85] | Prevention | LIFE, PSR | CSQ > 27 | SCID for DSM-IV-NP to exclude those with comorbid diagnosis, Treatment Services Review (TSR) |

| Study | Selection Bias | Study Design | Confounders | Blinding | Data Collection Methods | Withdrawal or Drop-Outs | Intervention Integrity | Analysis | Overall Rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bhat et al. (2017) [44] | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Bowen et al. (2014) [45] | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Brandon et al. (2012) [21] | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Chen (2011) [46] | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 |

| Chung (2015) [47] | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Clark et al. (2003) [48] | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Crockett et al. (2008) [49] | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Deans et al. (2016) [50] | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Dennis et al. (2020) [51] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Field et al. (2009) [52] | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Field et al. (2013) [53] | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Forman et al. (2007) [54] | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| L. L. Gao et al. (2010) [55] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| L. L. Gao et al. (2012) [56] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| L. L. Gao et al. (2012) [57] | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| L. L. Gao et al. (2014) [58] | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| L. L. Gao et al. (2015) [59] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Grote et al. (2004) [60] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Grote et al. (2009) [61] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Grote et al. (2015) [62] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Grote et al. (2017) [63] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Hajiheidari et al. (2013) [64] | 3 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Kao et al. (2015) [65] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Klier et al. (2001) [66] | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| Kozinszky, Dudas, Devosa, Csatordai, Tóth, et al. (2012) [67] | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Lenze et al. (2015) [68] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Lenze and Potts (2017) [69] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Leung and Lam (2012) [70] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Moel et al. (2010) [71] | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Mulcahy et al. (2010) [72] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Nylen et al. (2010) [73] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| O’Hara et al. (2000) [74] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| O’Hara et al. (2019) [75] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Pearlstein et al. (2006) [76] | 1 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Posmontier et al. (2016) [77] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Posmontier et al. (2019) [78] | 1 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| Reay et al. (2006) [79] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| M. G. Spinelli (1997) [19] | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 |

| Spinelli and Endicott (2003) [20] | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Spinelli, Endicott, Leon, et al. (2013) [80] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Spinelli, Endicott, and Goetz (2013) [81] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Zlotnick et al. (2001) [82] | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Zlotnick et al. (2006) [83] | 3 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Zlotnick et al. (2011) [84] | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Zlotnick et al. (2016) [85] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bright, K.S.; Charrois, E.M.; Mughal, M.K.; Wajid, A.; McNeil, D.; Stuart, S.; Hayden, K.A.; Kingston, D. Interpersonal Psychotherapy to Reduce Psychological Distress in Perinatal Women: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8421. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228421

Bright KS, Charrois EM, Mughal MK, Wajid A, McNeil D, Stuart S, Hayden KA, Kingston D. Interpersonal Psychotherapy to Reduce Psychological Distress in Perinatal Women: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(22):8421. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228421

Chicago/Turabian StyleBright, Katherine S., Elyse M. Charrois, Muhammad Kashif Mughal, Abdul Wajid, Deborah McNeil, Scott Stuart, K. Alix Hayden, and Dawn Kingston. 2020. "Interpersonal Psychotherapy to Reduce Psychological Distress in Perinatal Women: A Systematic Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 22: 8421. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228421

APA StyleBright, K. S., Charrois, E. M., Mughal, M. K., Wajid, A., McNeil, D., Stuart, S., Hayden, K. A., & Kingston, D. (2020). Interpersonal Psychotherapy to Reduce Psychological Distress in Perinatal Women: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(22), 8421. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228421