Perceptions, Attitudes, and Knowledge toward Advance Directives: A Scoping Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

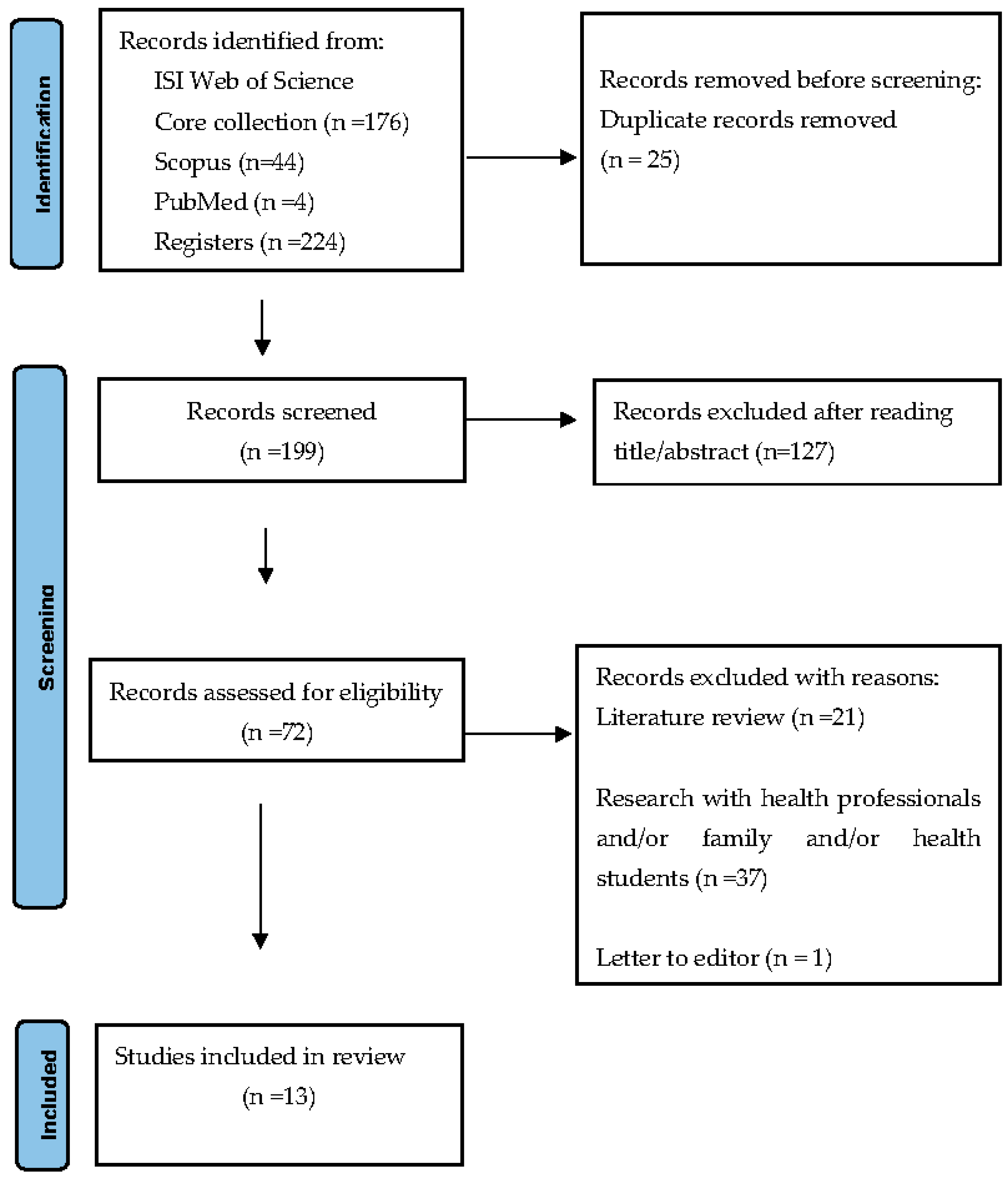

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

3. Results

3.1. General Data

| Main Author/Year/Country | Participants | Objectives | Methodology/Study Type | Main Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bar-Sela et al. (2021); Israel [41] | Advanced cancer patients (n = 109) | Evaluate the barriers and motives among Israeli cancer patients regarding advance care planning. | Mixed methods: cross-sectional, descriptive study | Participants mentioned that information and open communication were the main enabling factor to complete advance care planning. Communication with staff was rated more significant than with family members. The main motive to complete advance care planning was to ensure that the best medical decisions would be made and to avoid unnecessary medical procedures. Most of the participants did not hear about advance care planning from another source outside the hospital. Participants mentioned that the correct timing for implementing the ACP was during the terminal stage of the disease. |

| Cadmus et al. (2019); Nigeria [50] | A person aged 60 years and above (n = 34) | Explore the knowledge, attitude, and belief of older persons regarding decision making surrounding end-of-life life and advance directives. | Qualitative: exploratory study | The older person said they knew the term advance directives; however, when asked about care to receive or refuse, they could not answer. Most older persons preferred to have their children (first male son) as the major decision makers after their demise. Barriers to the implementation of advance directives were high legal fees and cultural rites and practices. |

| Carbonneau et al. (2018); Canada [42] | Patients with cirrhosis (n = 17) | Explore patients’ experiences and perceptions of the advance care planning (ACP) process in cirrhosis. | Qualitative: exploratory study | Participants expressed an overall lack of understanding of the role of advance care planning (ACP) processes. Most participants had a substitute decision maker. All participants mentioned the involvement of the family in the ACP process. Many saw ACP as critical to reducing the decision-making burden on the family. All participants agreed that discussions/conversations about ACP should happen outside of the hospital and not during acutely ill periods. Early anticipatory planning that requires discussion/conversation should be initiated in primary and outpatient care contexts. |

| Dhingra et al. (2020); USA [49] | Chinese American Immigrants older adults (n = 179) | Describe attitudes and beliefs concerning ACP in older, non-English-speaking Chinese Americans. | Quantitative: exploratory study | A total of 84.9% never completed an advance directive. A total of 56.8% were unfamiliar with any of the advance directives. A total of 74.4% were willing to complete one in the future. The rate of patients in ACP among Chinese immigrants is about half that of the general U.S. population. |

| Hou et al. (2021); China [43] | Patients with advanced cancer (n = 275) | Describe the knowledge and attitude of Chinese patients with advanced cancer toward advance care planning (ACP). | Quantitative: exploratory study | A total of 82.2% of patients had never heard about ACP. A total of 83.0% of patients had never talked about ACP. A total of 18.3% of patients were not willing to talk about ACP. A total of 67.8% of patients chose to refuse resuscitation attempts or life-sustaining medical interventions. A total of 70.8% of patients expressed a desire to have surrogate decision makers in the event they became unconscious, with their spouses being identified as the most significant proxy decision maker. Age, gender, place of residence, educational status, and family economic status were independent predictors of ACP. |

| Kim et al. (2018); Republic of Korea [44] | Older people with chronic diseases (n = 112) | Examine knowledge, attitudes, and barriers/benefits regarding advance directives (Ads) and their associations with AD treatment preferences among chronically ill, low-income, community-dwelling older people. | Quantitative: descriptive correlational study | A total of 8.9% of the participants knew about ADs. A total of 54.5% of the participants preferred hospice care. Few of the participants preferred aggressive treatments: 14.3% cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), 9.8% ventilation support, and 8.9% haemodialysis. Being married was associated with the likelihood of preferring CPR and ventilation support. Higher education was associated with preferring the likelihood of CPR and haemodialysis. Having a cardiovascular disease/stroke was associated with the likelihood of preferring CPR and hospice care. Greater perceived barriers increased the likelihood of CPR preference and decreased the likelihood of hospice care. Greater perceived benefits decreased the likelihood of CPR and ventilation support. Advance directives knowledge decreased the likelihood of haemodialysis preference. |

| Kleiner et al. (2019); Switzerland [12] | Older adults aged ≥71 (n = 1701) | Test the hypothesis of an association between increased knowledge of ACP and a more positive perception. | Quantitative: descriptive, correlational study | A total of 47% of the participants were aware of the legal dispositions for ACP. A total of 14% of the participants had completed or were in the process of completing an AD. There is a positive association between the knowledge of ACP and a more positive perception of ADs. |

| Laranjeira et al. (2021); Portugal [15] | Adults (aged ≥18 years) (n = 1028) | Assess the knowledge, attitudes, and preferences of a sample of Portuguese adults regarding end-of-life care decisions and advance care directives. | Quantitative: descriptive, correlational study | A total of 26.63% of the participants were unaware of what an advance care directive (ACD) was. A total of 2.4% of the participants had an ACD. Higher levels of knowledge were associated with more positive attitudes. |

| Lim et al. (2022); Malaysia [51] | Adults (n = 385) | To assess the knowledge, attitude, and practice of community-dwelling adults and their associated factors. | Quantitative: cross-sectional, descriptive study | A total of 5.2% of the participants were aware of ACP. A total of 85.7% of the participants had a positive attitude toward ACP. A total of 84.4% of the participants felt that ACP was necessary and would consider discussing an ACP. |

| Schnur et al. (2019); EUA [48] | Young adults aged 18–26 years (n = 147) | Identify associations among young adults’ characteristics, knowledge of ACP, and readiness to engage ACP-related behaviours. | Quantitative: cross-sectional, descriptive, correlational study | A total of 93.2% of the participants reported thinking that good quality of life was more important than living as long as possible. A total of 84.7% of the participants scored positive toward ACP. A total of 78.9% of the participants scored a positive disposition toward the ACP process. Less than 4% of the participants reported engaging in ACP-related conversations with their doctors or healthcare providers. Higher ACP knowledge scores were weakly associated with more positive views of ACP. |

| Sprange et al. (2019); Canada [45] | Cirrhosis patients (n = 97) | Assess knowledge and recall of participation in ACP. | Mixed: exploratory study | A total of 33% of the participants had completed a personal directive (PD). A total of 14% of the participants had completed a goals of care designation (GCD). A total of 78% of the participants believed that GDC is important. A total of 84.5% of the participants preferred initiating the ACP discussion in an outpatients’ clinic setting. The participants considered specific qualities during the ACP discussion:

|

| Ugalde et al. (2018); Australia [46] | Cancer patients (n = 14) | Explore the comprehension of ACP in people with cancer who have current advance care plans. | Qualitative: exploratory, descriptive study | Most participants demonstrated partial comprehension of their advance care plan. Participants’ attitudes and their written documents’ congruence were limited. Most participants reported creating an ACP was helpful because of the following reasons:

|

| Wang et al. (2021); China [47] | Participants were patients with brain tumours who were older than 18 years and were reported. (n = 316) | Describe the knowledge and preferences of ADs and end-of-life care decisions of patients with tumorous. | Qualitative: cross-sectional, correlational study | A total of 88.61% of the participants had never heard of ADs. A total of 65.18% of the participants reported that they would like to make an AD. For those who would like to make an AD, the primary reasons were as follows: Ensure comfort at the end of life. Reduce financial burdens on their family. For those who would not like to make ADs, the primary reason was as follows: Lack of familiarity with the concept of ADs. Belief that doctors or family members would make decisions for them. A total of 79.43% of the participants wanted to discuss end-of-life arrangements with medical staff. A total of 63.29% of the participants were willing to receive end-of-life care, even though it would not delay death. Knowledge of ADs, receiving surgery or radiotherapy, age lower than 70 years, male sex, educational qualification of college and beyond, without children, medical insurance for nonworking or working urban residents, and self-payment of medical expenses were significant predictors of preferring to make ADs. |

3.2. Perceptions, Attitudes, and Knowledge

3.3. AD Completion

3.4. Correlation Factors and Predictors

3.5. Communication and Planning

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Implications for Practice and Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Veshi, D.; Neitzke, G. Advance Directives in Some Western European Countries: A Legal and Ethical Comparison. Eur. J. Health Law 2015, 22, 321–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, H.Y. Advance Directives: Rethinking Regulation, Autonomy & Healthcare Decision-Making; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Nunes, R. Directivas Anticipadas de Voluntad; Consejo Federal de Medicina: Brasília, Brazil, 2020; Available online: http://portal.cfm.org.br/ (accessed on 27 March 2023).

- Benzenhöfer, U.; Hack-Molitor, G. Luis Kutner and the Development of the Advance Directive (Living Will); Benzeenhöfer, O., Ed.; GWAB: Wetzlar, Germany, 2009; Available online: http://publikationen.ub.uni-frankfurt.de/frontdoor/index/index/docId/34515 (accessed on 3 September 2023).

- Kutner, L. Due Process of Euthanasia: The Living Will, A Proposal. Indiana Law J. 1969, 44, 539–554. [Google Scholar]

- Lack, P.; Biller-Andorno, N.; Brauer, S. (Eds.) Advance Directives. In International Library of Ethics, Law, and the New Medicine; Lack, P.; Biller-Andorno, N.; Brauer, S. (Eds.) Springer Dordrecht: Heidelberg, Germany; New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2014; Available online: http://www.springer.com/series/6224 (accessed on 13 March 2023).

- Andorno, R.; Biller-Andorno, N.; Brauer, S.; Biller-Andorno, N. Advance health care directives: Towards a coordinated European policy? Eur. J. Health Law 2009, 16, 207–227. Available online: https://brill.com/view/journals/ejhl/16/3/article-p207_2.xml (accessed on 27 April 2021). [CrossRef]

- ten Have, H.; Neves, M.d.C.P. Dictionary of Global Bioethics. In Dictionary of Global Bioethics; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation Office of Disability, Aging and Long-Term Care Policy. Advance Directives and Advance Care Planning: Report to Congress; ASPE: Washington, DC, USA, 2008; Available online: https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/advance-directives-advance-care-planning-report-congress-0 (accessed on 28 June 2021).

- Yadav, K.N.; Gabler, N.B.; Cooney, E.; Kent, S.; Kim, J.; Herbst, N.; Mante, A.; Halpern, S.D.; Courtright, K.R. Approximately one in three us adults completes any type of advance directive for end-of-life care. Health Aff. 2017, 36, 1244–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silveira, M.J.; Wiitala, W.; Piette, J. Advance directive completion by elderly Americans: A decade of change. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2014, 62, 706–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleiner, A.C.; Santos-Eggimann, B.; Fustinoni, S.; Dürst, A.-V.; Haunreiter, K.; Rubli-Truchard, E.; Seematter-Bagnoud, L. Advance care planning dispositions: The relationship between knowledge and perception. BMC Geriatr. 2019, 19, 118. [Google Scholar]

- Rurup, M.L.; Onwuteaka-Philipsen, B.D.; Van Der Heide, A.; Van Der Wal, G.; Deeg, D.J.H. Frequency and determinants of advance directives concerning end-of-life care in the Netherlands. Soc. Sci. Med. 2006, 62, 1552–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wijmen, M.P.S.; Rurup, M.L.; Pasman, H.R.W.; Kaspers, P.J.; Onwuteaka-Philipsen, B.D. Advance directives in the netherlands: An empirical contribution to the exploration of a cross-cultural perspective on advance directives. Bioethics 2010, 24, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laranjeira, C.; Dixe, M.D.A.; Gueifão, L.; Caetano, L.; Passadouro, R.; Querido, A. Awareness and Attitudes towards Advance Care Directives (ACDs): An Online Survey of Portuguese Adults. Healthcare 2021, 9, 648. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34072558 (accessed on 20 March 2023). [CrossRef]

- De Vleminck, A.; Pardon, K.; Houttekier, D.; Van Den Block, L.; Vander Stichele, R.; Deliens, L. The prevalence in the general population of advance directives on euthanasia and discussion of end-of-life wishes: A nationwide survey Ethics, organization and policy. BMC Palliat. Care 2015, 14, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herreros, B.; Gella, P.; Valenti, E.; Márquez, O.; Moreno, B.; Velasco, T. Improving the Implementation of Advance Directives in Spain. Camb. Q. Healthc. Ethics 2023, 32, 270–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buck, K.; Nolte, L.; Sellars, M.; Sinclair, C.; White, B.P.; Kelly, H.; Macleod, A.; Detering, K.M. Advance care directive prevalence among older Australians and associations with person-level predictors and quality indicators. Health Expect. 2021, 24, 1312–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, B.; Tilse, C.; Wilson, J.; Rosenman, L.; Strub, T.; Feeney, R.; Silvester, W. Prevalence and predictors of advance directives in Australia. Intern. Med. J. 2014, 44, 975–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capelas, M.L.V.; Coelho, S.P.F.; da Silva, S.C.F.S.; Ferreira, C.M.D.; Pereira, C.M.F.; Alvarenga, M.I.S.F.; de Sousa Freitas, M. Os Portugueses eo Testamento Vital. Cad. Saúde 2017, 9, 44–53. [Google Scholar]

- Portugal—SPMS. Registo de Testamentos Vitais Duplicou em 2022—SPMS. 2023. Available online: https://www.spms.min-saude.pt/2023/01/registo-de-testamentos-vitais-duplicou-em-2022/ (accessed on 13 March 2023).

- Aguilar-Sánchez, J.M.; Cabañero-Martínez, M.J.; Puerta Fernández, F.; Ladios-Martín, M.; Fernández-de-Maya, J.; Cabrero-García, J. Knowledge and attitudes of health professionals towards advance directives|Grado de conocimiento y actitudes de los profesionales sanitarios sobre el documento de voluntades anticipadas. Gac. Sanit. 2018, 32, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartwright, C.M.; White, B.P.; Willmott, L.; Williams, G.; Parker, M.H. Palliative care and other physicians’ knowledge, attitudes and practice relating to the law on withholding/withdrawing life-sustaining treatment: Survey results. Palliat. Med. 2016, 30, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastbom, L.; Milberg, A.; Karlsson, M. ‘We have no crystal ball’—Advance care planning at nursing homes from the perspective of nurses and physicians. Scand. J. Prim. Health Care 2019, 37, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S.A.; Kolomer, S. Advance care planning in South Korea: Social work perspective. Soc. Work Health Care 2016, 55, 545–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaona-Flores, V.A.; Campos-Navarro, L.A.; Ocampo-Martínez, J.; Alcalá-Martínez, E.; Patiño-Pozas, M. Knowledge of the “advance directive” in physicians at tertiary care hospitals|La «voluntad anticipada» y su conocimiento por médicos en hospitales de tercer nivel. Gac. Med. Mex. 2016, 152, 486–494. [Google Scholar]

- Gimeno, M.M.; Escribano, C.C.; Fernández, T.H.; García, M.O.; Benito, D.T.; Arenas, T.B.G.; Almagro, P.R. Knowledge and attitudes of health care professionals in advance healthcare directives|Conocimientos y actitudes sobre voluntades anticipadas en profesionales sanitarios. J. Healthc. Qual. Res. 2018, 33, 270–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, M.B.; McGregor, M.J.; Huggins, M.; Moorhouse, P.; Mallery, L.; Bauder, K. Evaluation of an initiative to improve advance care planning for a home-based primary care service. BMC Geriatr. 2021, 21, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Pozo Puente, K.; Hidalgo, J.L.T.; Herráez, M.J.S.; Bravo, B.N.; Rodríguez, J.O.; Guillén, V.G. Study of the factors influencing the preparation of advance directives. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2014, 58, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Detering, K.M.; Hancock, A.D.; Reade, M.C.; Silvester, W. The impact of advance care planning on end of life care in elderly patients: Randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2010, 340, c1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixon, J.; King, D.; Knapp, M. Advance care planning in England: Is there an association with place of death? Secondary analysis of data from the National Survey of Bereaved People. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2019, 9, 316–325. Available online: http://spcare.bmj.com/ (accessed on 13 March 2023). [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, C.; Nunes, R. Living will: Information verification and sharing in a Portuguese hospital. Rev. Bioét. 2019, 27, 691–698. Available online: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1983-80422019000400691&tlng=pt (accessed on 27 April 2021). [CrossRef]

- Martins, C.S.; Sousa, I.; Barros, C.; Pires, A.; Castro, L.; Santos, C.d.C.; Nunes, R. Do surrogates predict patient preferences more accurately after a physician-led discussion about advance directives? A randomized controlled trial. BMC Palliat. Care 2022, 21, 122. Available online: https://bmcpalliatcare.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12904-022-01013-3 (accessed on 4 November 2022). [CrossRef]

- Knight, T.; Malyon, A.; Fritz, Z.; Subbe, C.; Cooksley, T.; Holland, M.; Lasserson, D. Advance care planning in patients referred to hospital for acute medical care: Results of a national day of care survey. eClinicalMedicine 2020, 19, 100235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silveira, M.J.; Kim, S.Y.H.; Langa, K.M. Advance Directives and Outcomes of Surrogate Decision Making before Death. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 362, 1211–1218. Available online: https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMsa0907901 (accessed on 23 March 2023). [CrossRef]

- Baharoon, S.; Alzahrani, M.; Alsafi, E.; Layqah, L.; Al-Jahdali, H.; Ahmed, A. Advance directive preferences of patients with chronic and terminal illness towards end of life decisions: A sample from Saudi Arabia|Préférences en matière de directives anticipées de patients atteints de maladie chronique en phase terminale quant aux. East. Mediterr. Health J. 2019, 25, 791–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, R.Y.-N.; Wong, E.L.-Y.; Kiang, N.; Chau, P.Y.-K.; Lau, J.Y.; Wong, S.Y.-S.; Yeoh, E.-K.; Woo, J.W. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Preferences of Advance Decisions, End-of-Life Care, and Place of Care and Death in Hong Kong. A Population-Based Telephone Survey of 1067 Adults. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2017, 18, 367.e19–367.e27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, A.S.; Wenger, N.S.; Sarkisian, C.A. Opiniones: End-of-life care preferences and planning of older latinos. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2010, 58, 1109–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yen, C.-C.; Lin, C.-P.; Su, Y.-T.; Tsu, C.-H.; Chang, L.-M.; Sun, Z.-J.; Lin, B.-S.; Wu, J.-S. The Characteristics and Motivations of Taiwanese People toward Advance Care Planning in Outpatient Clinics at a Community Hospital. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 1–8. Available online: https://click.endnote.com/viewer?doi=10.1136%2Fbmj.n71&token=WzE2OTgwMTcsIjEwLjExMzYvYm1qLm43MSJd.3wkYaeGzlm-5xsoOZ2PQ8fS609Y (accessed on 27 January 2023).

- Bar-Sela, G.; Bagon, S.; Mitnik, I.; Adi, S.; Baziliansky, S.; Bar-Sella, A.; Vornicova, O.; Tzuk-Shina, T. The perception and attitudes of Israeli cancer patients regarding advance care planning. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2021, 12, 1181–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbonneau, M.; Davyduke, T.; Spiers, J.; Brisebois, A.; Ismond, K.; Tandon, P. Patient views on advance care planning in cirrhosis: A qualitative analysis. Can. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 2018, 4040518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.-T.; Lu, Y.-H.; Yang, H.; Guo, R.-X.; Wang, Y.; Wen, L.-H.; Zhang, Y.-R.; Sun, H.-Y. The Knowledge and Attitude towards Advance Care Planning among Chinese Patients with Advanced Cancer. J. Cancer Educ. 2021, 36, 603–610. Available online: https://click.endnote.com/viewer?doi=10.1007%2Fs13187-019-01670-8&token=WzE2OTgwMTcsIjEwLjEwMDcvczEzMTg3LTAxOS0wMTY3MC04Il0.BtSnwfpyNgyYK1NakVQ9I2CJ4_s (accessed on 18 April 2023). [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Heo, S.; Hong, S.W.; Shim, J.; Lee, J.-A. Correlates of advance directive treatment preferences among community-dwelling older people with chronic diseases. Int. J. Older People Nurs. 2019, 14, e12229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprange, A.; Ismond, K.P.; Hjartarson, E.; Chavda, S.; Carbonneau, M.; Kowalczewski, J.; Watanabe, S.M.; Brisebois, A.; Tandon, P. Advance Care Planning Preferences and Readiness in Cirrhosis: A Prospective Assessment of Patient Perceptions and Knowledge. J. Palliat. Med. 2020, 23, 552–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugalde, A.; O’callaghan, C.; Byard, C.; Brean, S.; MacKay, J.; Boltong, A.; Davoren, S.; Lawson, D.; Parente, P.; Michael, N.; et al. Does implementation matter if comprehension is lacking? A qualitative investigation into perceptions of advance care planning in people with cancer. Support. Care Cancer 2018, 26, 3765–3771. Available online: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00520-018-4241-y (accessed on 18 April 2023). [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Hong, Y.; Zeng, P.; Hu, Z.; Xu, X.; Wang, H. Advance directives and end-of-life care: Knowledge and preferences of patients with brain Tumours from Anhui, China. BMC Cancer 2021, 21, 25. Available online: https://bmccancer.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12885-020-07775-4 (accessed on 28 June 2021). [CrossRef]

- Schnur, K.; Radhakrishnan, K. Young Adult Knowledge and Readiness to Engage in Advance Care Planning Behaviors. J. Hosp. Palliat. Nurs. 2019, 21, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhingra, L.; Cheung, W.; Breuer, B.; Huang, P.; Lam, K.; Chen, J.; Zhou, X.; Chang, V.; Chui, T.; Hicks, S.; et al. Attitudes and Beliefs toward Advance Care Planning among Underserved Chinese American Immigrants. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2020, 60, 588–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cadmus, E.O.; Adebusoye, L.A.; Olowookere, O.O.; Olusegun, A.T.; Oyinlola, O.; Adeleke, R.O.; Omobowale, O.C.; Alonge, T.O. Older persons’ perceptions about advanced directives and end of life issues in a geriatric care setting in southwestern nigeria. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2019, 32, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, M.K.; Lai, P.S.M.; Lim, P.S.; Wong, P.S.; Othman, S.; Mydin, F.H.M. Knowledge, attitude and practice of community-dwelling adults regarding advance care planning in Malaysia: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e048314. Available online: https://bmjopen.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-048314 (accessed on 6 March 2023). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kermel-Schiffman, I.; Werner, P. Knowledge regarding advance care planning: A systematic review. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2017, 73, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, B.P.; Willmott, L.; Tilse, C.; Wilson, J.; Ferguson, M.; Aitken, J.; Dunn, J.; Lawson, D.; Pearce, A.; Feeney, R. Prevalence of advance care directives in the community: A telephone survey of three Australian States. Intern. Med. J. 2019, 49, 1261–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, B. Nurses in the know: The history and future of advance directives. Online J. Issues Nurs. 2017, 22, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, A. Historical Review of Advance Directives. In Advance Directives. International Library of Ethics, Law, and the New Medicine; Lack, P., Biller-Andorno, N., Brauer, S., Eds.; Springer Dordrecht: Heidelberg, Germany; New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2014; pp. 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein, A.; Resnizky, S.; Cohen, Y.; Garber, R.; Kannai, R.; Katz, Y.; Avni, O. Promoting advance care planning (ACP) in community health clinics in Israel: Perceptions of older adults with pro-ACP attitudes and their family physicians. Palliat. Support. Care 2023, 21, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemsley, B.; Meredith, J.; Bryant, L.; Wilson, N.J.; Higgins, I.; Georgiou, A.; Hill, S.; Balandin, S.; McCarthy, S. An integrative review of stakeholder views on Advance Care Directives (ACD): Barriers and facilitators to initiation, documentation, storage, and implementation. Patient Educ. Couns. 2019, 102, 1067–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izumi, S. Advance care planning: The nurse’s role. Am. J. Nurs. 2017, 117, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lum, H.D.; Sudore, R.L.; Bekelman, D.B. Advance care planning in the elderly. Med. Clin. N. Am. 2015, 99, 391–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nauck, F.; Becker, M.; King, C.; Radbruch, L.; Voltz, R.; Jaspers, B. To what extent are the wishes of a signatory reflected in their advance directive: A qualitative analysis. BMC Med. Ethics 2014, 15, 52. Available online: https://bmcmedethics.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1472-6939-15-52 (accessed on 23 March 2023). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porensky, E.K.; Carpenter, B.D. Knowledge and perceptions in advance care planning. J. Aging Health 2008, 20, 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholten, G.; Bourguignon, S.; Delanote, A.; Vermeulen, B.; Van Boxem, G.; Schoenmakers, B. Advance directive: Does the GP know and address what the patient wants? Advance directive in primary care. BMC Med. Ethics 2018, 19, 58. Available online: https://bmcmedethics.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12910-018-0305-2 (accessed on 23 March 2023). [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, J.; Waller, A.; Sanson-Fisher, R.; Clark, K.; Ball, J. Knowledge of, and participation in, advance care planning: A cross-sectional study of acute and critical care nurses’ perceptions. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2018, 86, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunsaker, A.E.; Mann, A. An Analysis of the Patient Self-Determination Act of 1990. J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Environ. 2013, 23, 841–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, M.; Tompkins, C.; Scruggs, K.; Robles, J. Advance Directives Information Delivery in Medicare/Medicaid-Funded Agencies: An Exploratory Study. J. Soc. Work End Life Palliat. Care 2018, 14, 177–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parsons, J.A.; Johal, H.K. In defence of the bioethics scoping review: Largely systematic literature reviewing with broad utility. Bioethics 2022, 36, 423–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khairuddin, N.N.B.; Lau, S.T.; Ang, W.H.D.; Tan, P.H.; Goh, Z.W.D.; Ang, N.K.E.; Lau, Y. Implementing advance care planning: A qualitative exploration of nurses’ perceived benefits and challenges. J. Nurs. Manag. 2020, 28, 1080–1087. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jonm.13056 (accessed on 13 March 2023). [CrossRef]

- Macedo, J.C. Contribution to improve advance directives in Portugal. MOJ Gerontol. Geriatr. 2020, 5, 27–30. Available online: https://medcraveonline.com/MOJGG/contribution-to-improve-advance-directives-in-portugal.html (accessed on 10 October 2021). [CrossRef]

- Nunes, R. Ensaios de Bioética; Conselho Federal de Medicina: Brasília, Brazil; Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade do Porto: Porto, Portugal, 2017. [Google Scholar]

| Search Equation | Database | Results |

|---|---|---|

| Advance directives or advance care planning or living will (topic) and perception (topic) and attitudes (topic) and knowledge (topic) | WoS * (core collection) | 176 |

| (TITLE-ABS-KEY (advance directives) or TITLE-ABS-KEY (advance care planning) or TITLE-ABS-KEY (living will) and TITLE-ABS-KEY (perception) and TITLE-ABS-KEY (attitude) and TITLE-ABS-KEY (knowledge)) | Scopus | 44 |

| (((Advance directive [title/abstract]) or (advance care planning [title/abstract])) or (living will [title/abstract])) and (perception [title/abstract])) and (attitude [title/abstract])) and (knowledge [title/abstract] | PubMed | 4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Macedo, J.C.; Rego, F.; Nunes, R. Perceptions, Attitudes, and Knowledge toward Advance Directives: A Scoping Review. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2755. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11202755

Macedo JC, Rego F, Nunes R. Perceptions, Attitudes, and Knowledge toward Advance Directives: A Scoping Review. Healthcare. 2023; 11(20):2755. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11202755

Chicago/Turabian StyleMacedo, João Carlos, Francisca Rego, and Rui Nunes. 2023. "Perceptions, Attitudes, and Knowledge toward Advance Directives: A Scoping Review" Healthcare 11, no. 20: 2755. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11202755