Sexual Motivation (Desire): Problems with Current Preclinical and Clinical Evaluations of Treatment Effects and a Solution

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Drugs Approved for Treatment of Sexual Dysfunctions: Clinical Data

3. Drugs Approved for Treatment of Sexual Dysfunctions: Preclinical Data

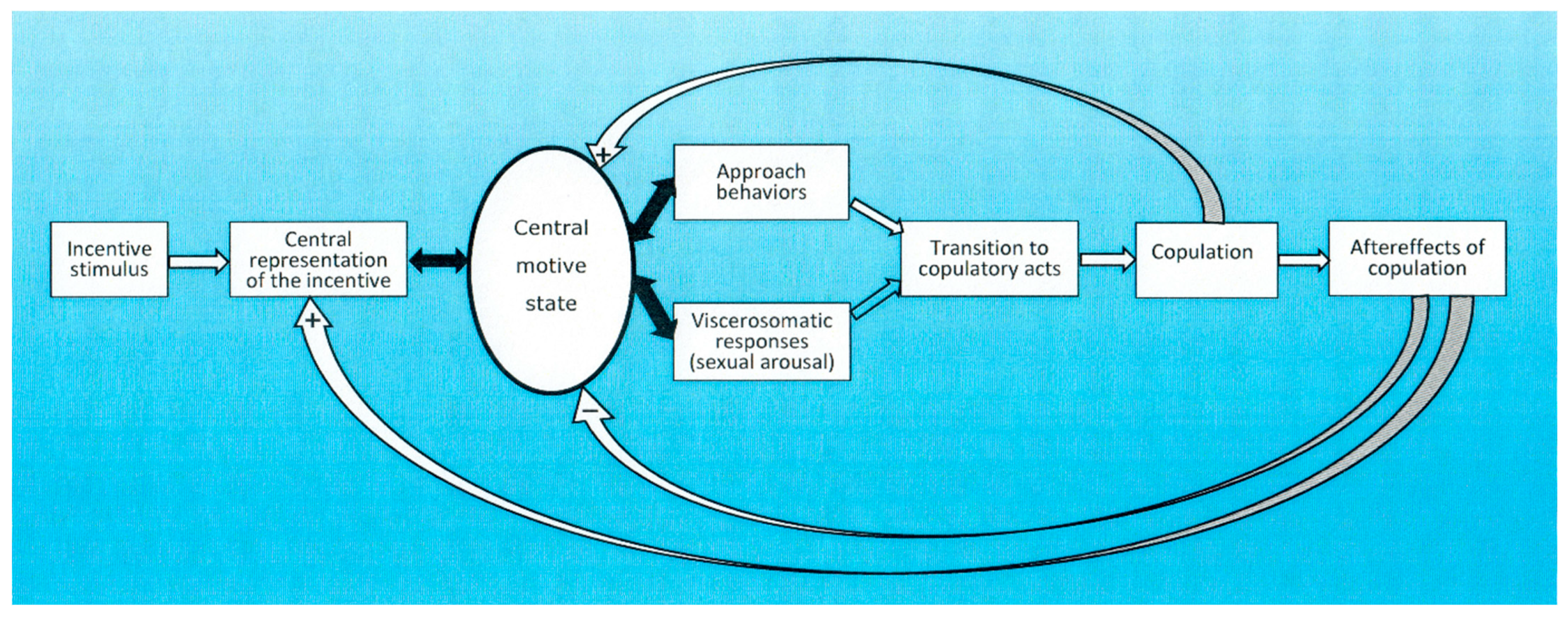

4. Conceptual Frameworks for Understanding Sexual Motivation

5. Unconscious and Conscious Processes

6. The Unconscious Made Conscious

7. Quantification of Sexual Motivation: Humans

8. Quantification of Sexual Motivation: Non-Human Animals

9. The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Guidelines for Evaluating Drugs for Treating Low Sexual Interest, Desire, and Arousal in Women

10. Proposals for the Future

11. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alexander, M. G., & Fisher, T. D. (2003). Truth and consequences: Using the bogus pipeline to examine sex differences in self-reported sexuality. Journal of Sex Research, 40(1), 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fifth edition, text revision (DSM-5-TR). American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R. M. (2013). Positive sexuality and its impact on overall well-being. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz, 56(2), 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnow, B. A., Millheiser, L., Garrett, A., Lake Polan, M., Glover, G. H., Hill, K. R., Lightbody, A., Watson, C., Banner, L., Smart, T., Buchanan, T., & Desmond, J. E. (2009). Women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder compared to normal females: A functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Neuroscience, 158(2), 484–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avitsur, R., & Yirmiya, R. (1999). The partner preference paradigm: A method to study sexual motivation and performance of female rats. Brain Research Protocols, 3, 320–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ågmo, A. (1999). Sexual motivation. An inquiry into events determining the occurrence of sexual behavior. Behavioural Brain Research, 105(1), 129–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ågmo, A. (2002). Copulation-contingent aversive conditioning and sexual incentive motivation in male rats: Evidence for a two-stage process of sexual behavior. Physiology and Behavior, 77(2–3), 425–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ågmo, A. (2015). Sexual behavior. In I. P. Stolerman, & L. H. Price (Eds.), Encyclopedia pf Psychopharmacology (pp. 1569–1575). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ågmo, A. (2024). Neuroendocrinology of sexual behavior. International Journal of Impotence Research, 36(4), 305–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ågmo, A., & Laan, E. (2023). The sexual incentive motivation model and its clinical applications. Journal of Sex Research, 60(7), 969–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ågmo, A., & Laan, E. (2024). Sexual incentive motivation and sexual behavior: The role of consent. Annual Review of Psychology, 75, 33–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ågmo, A., Turi, A. L., Ellingsen, E., & Kaspersen, H. (2004). Preclinical models of sexual desire: Conceptual and behavioral analyses. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior, 78, 379–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beach, F. A. (1976). Sexual attractivity, proceptivity, and receptivity in female mammals. Hormones and Behavior, 7, 105–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beach, F. A., & Jordan, L. (1956). Sexual exhaustion and recovery in the male rat. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 8(3), 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benz, F., Riemann, D., Domschke, K., Spiegelhalder, K., Johann, A. F., Marshall, N. S., & Feige, B. (2023). How many hours do you sleep? A comparison of subjective and objective sleep duration measures in a sample of insomnia patients and good sleepers. Journal of Sleep Research, 32(2), e13802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergheim, D., Chu, X., & Ågmo, A. (2015). The function and meaning of female rat paracopulatory (proceptive) behaviors. Behavioural Processes, 118, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernabé, J., Rampin, O., Giuliano, F., & Benoit, G. (1995). Intracavernous pressure changes during reflexive penile erections in the rat. Physiology and Behavior, 57(5), 837–841. [Google Scholar]

- Bielert, C., & van der Walt, L. A. (1982). Male Chacma baboon (Papio ursinus) sexual arousal: Mediation by visual cues from female conspecifics. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 7(1), 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanchflower, D. G., & Oswald, A. J. (2004). Money, sex and happiness: An empirical study. Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 106(3), 393–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloemers, J., Gerritsen, J., Bults, R., Koppeschaar, H., Everaerd, W., Olivier, B., & Tuiten, A. (2010). Induction of sexual arousal in women under conditions of institutional and ambulatory laboratory circumstances: A comparative study. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 7(3), 1160–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumenstock, S. M., Suschinsky, K., Brotto, L. A., & Chivers, M. L. (2024). Genital arousal and responsive desire among women with and without sexual interest/arousal disorder symptoms. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 21(6), 539–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohlen, J. G., Held, J. P., & Sanderson, M. O. (1980). The male orgasm: Pelvic contractions measured by anal probe. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 9(6), 503–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohlen, J. G., Held, J. P., Sanderson, M. O., & Ahlgren, A. (1982). The female orgasm: Pelvic contractions. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 11(5), 367–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boolell, M., Allen, M. J., Ballard, S. A., Gepi-Attee, S., Muirhead, G. J., Naylor, A. M., Osterloh, I. H., & Gingell, C. (1996). Sildenafil: An orally active type 5 cyclic GMP-specific phosphodiesterase inhibitor for the treatment of penile erectile dysfunction. International Journal of Impotence Research, 8(2), 47–52. [Google Scholar]

- Borland, J. M., Kohut-Jackson, A. L., Peyla, A. C., Hall, M. A. L., Mermelstein, P. G., & Meisel, R. L. (2025). Female Syrian hamster analyses of bremelanotide, a US FDA approved drug for the treatment of female hypoactive sexual desire disorder. Neuropharmacology, 267, 110299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brand, A., Waterink, W., & van Lankveld, J. (2024). Automatic associations between sexual function problems and pursuing help in pelvic physical therapy practice: The psychometric investigation of an implicit association test. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 50(5), 627–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullock, C. M., & Beckson, M. (2011). Male victims of sexual assault: Phenomenology, psychology, physiology. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, 39(2), 197–205. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cado, S., & Leitenberg, H. (1990). Guilt reactions to sexual fantasies during intercourse. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 19(1), 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerwenka, S., Dekker, A., Pietras, L., & Briken, P. (2021). Single and multiple orgasm experience among women in heterosexual partnerships. Results of the German Health and Sexuality Survey (GeSiD). Journal of Sexual Medicine, 18(12), 2028–2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chadwick, S. B., Grower, P., & van Anders, S. M. (2022). Coercive sexual experiences that include orgasm predict negative psychological, relationship, and sexual outcomes. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(23–24), NP22199–NP22225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z., & Smyth, R. (2015). Sex and happiness. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 112, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childress, A. R., Ehrman, R. N., Wang, Z., Li, Y., Sciortino, N., Hakun, J., Jens, W., Suh, J., Listerud, J., & Marquez, K. (2008). Prelude to passion: Limbic activation by “unseen” drug and sexual cues. PLoS ONE, 3(1), e1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chivers, M. L., Seto, M. C., Lalumiere, M. L., Laan, E., & Grimbos, T. (2010). Agreement of self-reported and genital measures of sexual arousal in men and women: A meta-analysis. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 39(1), 5–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, X., & Ågmo, A. (2014). Sociosexual behaviours in cycling, intact female rats (Rattus norvegicus) housed in a seminatural environment. Behaviour, 151(8), 1143–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, X., & Ågmo, A. (2015a). Sociosexual behaviors during the transition from non-receptivity to receptivity in rats housed in a seminatural environment. Behavioural Processes, 113, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, X., & Ågmo, A. (2015b). Sociosexual behaviors of male rats (Rattus norvegicus) in a seminatural environment. Journal of Comparative Psychology, 129(2), 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cieri-Hutcherson, N. E., Jaenecke, A., Bahia, A., Lucas, D., Oluloro, A., Stimmel, L., & Hutcherson, T. C. (2021). Systematic review of l-arginine for the treatment of hypoactive sexual desire disorder and related conditions in women. Pharmacy, 9(2), 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipriani, S., Alfaroli, C., Maseroli, E., & Vignozzi, L. (2023). An evaluation of bremelanotide injection for the treatment of hypoactive sexual desire disorder. Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy, 24(1), 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clayton, A., Jayne, C., Jacobs, M., Kimura, T., Pyke, R., & Lewis-D’Agostino, D. (2009). Efficacy of flibanserin as a potential treatment for Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder in North American premenopausal women: Results from the DAHLIA trial. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 6, 408–409. [Google Scholar]

- Clement, P., Laurin, M., Compagnie, S., Facchinetti, P., Bernabe, J., Alexandre, L., & Giuliano, F. (2012). Effect of dapoxetine on ejaculatory performance and related brain neuronal activity in rapid ejaculator rats. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 9(10), 2562–2573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darling, C. A., Davidson, J. K., & Jennings, D. A. (1991). The female sexual response revisited: Understanding the multiorgasmic experience in women. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 20(6), 527–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, S. R. (2024). Sexual dysfunction in women. New England Journal of Medicine, 391(8), 736–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeRogatis, L., Clayton, A., Lewis-D’Agostino, D., Wunderlich, G., & Fu, Y. L. (2008). Validation of the female sexual distress scale-revised for assessing distress in women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 5(2), 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeRogatis, L. R., Komer, L., Katz, M., Moreau, M., Kimura, T., Garcia, M., Wunderlich, G., & Pyke, R. (2012). Treatment of hypoactive sexual desire disorder in premenopausal women: Efficacy of flibanserin in the VIOLET study. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 9(4), 1074–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewitte, M. (2015). Gender differences in liking and wanting sex: Examining the role of motivational context and implicit versus explicit processing. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 44(6), 1663–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewsbury, D. A. (1972). Patterns of copulatory behavior in male mammals. Quarterly Review of Biology, 47(1), 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewsbury, D. A., & Pierce, J. D., Jr. (1989). Copulatory patterns of primates as viewed in broad mammalian perspective. American Journal of Primatology, 17(1), 51–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diamond, L. E., Earle, D. C., Heiman, J. R., Rosen, R. C., Perelman, M. A., & Harning, R. (2006). An effect on the subjective sexual response in premenopausal women with sexual arousal disorder by bremelanotide (PT-141), a melanocortin receptor agonist. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 3(4), 628–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, L. E., Earle, D. C., Rosen, R. C., Willett, M. S., & Molinoff, P. B. (2004). Double-blind, placebo-controlled evaluation of the safety, pharmacokinetic properties and pharmacodynamic effects of intranasal PT-141, a melanocortin receptor agonist, in healthy males and patients with mild-to-moderate erectile dysfunction. International Journal of Impotence Research, 16(1), 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dienberg, M. F., Oschatz, T., Piemonte, J. L., & Klein, V. (2023). Women’s orgasm and its relationship with sexual satisfaction and well-being. Current Sexual Health Reports, 15(3), 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixson, A. F. (1983). Observations on the evolution and behavioral significance of “sexual skin” in female primates. Advances in the Study of Behavior, 13, 63–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dording, C. M., & Sangermano, L. (2018). Female sexual dysfunction: Natural and complementary treatments. Focus: Journal of Life Long Learning in Psychiatry, 16(1), 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmers-Sommer, T. M., Allen, M., Schoenbauer, K. V., & Burrell, N. (2018). Implications of sex guilt: A meta-analysis. Marriage and Family Review, 54(5), 417–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, K. E., Lin, L., Bruner, D. W., Cyranowski, J. M., Hahn, E. A., Jeffery, D. D., Reese, J. B., Reeve, B. B., Shelby, R. A., & Weinfurt, K. P. (2016). Sexual satisfaction and the importance of sexual health to quality of life throughout the life course of U.S. adults. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 13(11), 1642–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Food and Drug Administration. (2016). Low sexual interest, desire, and/or arousal in women: Developing drugs for treatment. Guidance for industry; US Department of Health and Human Services, FDA. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/files/drugs/published/Low-Sexual-Interest--Desire--and-or-Arousal-in-Women--Developing-Drugs-for-Treatment-Guidance-for-Industry.pdf (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- Forbes, M. K., Baillie, A. J., & Schniering, C. A. (2014). Critical flaws in the Female Sexual Function Index and the International Index of Erectile Function. Journal of Sex Research, 51(5), 485–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freud, S. (1915). Das Unbewusste. Internationale Zeitschrift für ärztliche Psychoanalyse, 3(4), 189–203. [Google Scholar]

- Freud, S. (1917). Vorlesungen zur Einführung in die Psychoanalyse. H. Heller. [Google Scholar]

- Frühauf, S., Gerger, H., Schmidt, H. M., Munder, T., & Barth, J. (2013). Efficacy of psychological interventions for sexual dysfunction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 42(6), 915–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagnon, J. H. (1990). The explicit and implicit use of the scripting perspective in sex research. Annual Review of Sex Research, 1(1), 1–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagnon, J. H., & Simon, W. (2002). Sexual conduct: The social sources of human sexuality (2nd ed.). AldineTransaction. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, P., Liu, X., Zhu, T., Gao, R., Gao, J., Zhang, Y., Jiang, H., Huang, H., & Zhang, X. (2023). Vital function of DRD4 in dapoxetine medicated premature ejaculation treatment. Andrology, 11(6), 1175–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gawronski, B. (2009). Ten frequently asked questions about implicit measures and their frequently supposed, but not entirely correct answers. Canadian Psychology-Psychologie Canadienne, 50(3), 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelez, H., Greggain-Mohr, J., Pfaus, J. G., Allers, K. A., & Giuliano, F. (2013). Flibanserin treatment increases appetitive sexual motivation in the female rat. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 10(5), 1231–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gengo, P., Marson, L., & Gravitt, K. (2005, December 4–7). Actions of dapoxetine on ejaculation and sexual behaviour in rats. 8th Congress of the European Society for Sexual Medicine, Copenhagen, Denmark. Abstract MP1-074. [Google Scholar]

- Gezginci, E., Ata, A., & Goktas, S. (2024). The impact of male urinary incontinence on quality of life and sexual health. International Journal of Urological Nursing, 18(3), e12418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillath, O., & Canterberry, M. (2012). Neural correlates of exposure to subliminal and supraliminal sexual cues. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 7(8), 924–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillath, O., & Collins, T. (2016). Unconscious desire: The affective and motivational aspects of subliminal sexual priming. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 45(1), 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliano, F., Bernabé, J., Rampin, O., Courtois, F., Benoit, G., & Rosseau, J. P. (1994). Telemetric monitoring of intracavernous pressure in freely moving rats during copulation. Journal of Urology, 152(4), 1271–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldstein, I., Burnett, A. L., Rosen, R. C., Park, P. W., & Stecher, V. J. (2019). The serendipitous story of sildenafil: An unexpected oral therapy for erectile dysfunction. Sexual Medicine Reviews, 7(1), 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, S., & Goldstein, I. (2024). Use of bremelanotide (Vyleesi) in menwith sexual dysfunctions. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 21(Si), 1146–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwald, A. G., & Banaji, M. R. (2017). The implicit revolution: Reconceiving the relation between conscious and unconscious. American Psychologist, 72(9), 861–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenwald, A. G., McGhee, D. E., & Schwartz, J. L. (1998). Measuring individual differences in implicit cognition: The implicit association test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(6), 1464–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, N. (2022). The implicit achievement motive in the writing style. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research, 51(5), 1143–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, N., & Jockisch, A. (2020). Are GRU cells more specific and LSTM cells more sensitive in motive classification of text? Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence, 3, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, N., & Kreuzpointner, L. (2013). Measuring the reliability of picture story exercises like the TAT. PLoS ONE, 8(11), e79450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiman, J. R., Rupp, H., Janssen, E., Newhouse, S. K., Brauer, M., & Laan, E. (2011). Sexual desire, sexual arousal and hormonal differences in premenopausal US and Dutch women with and without low sexual desire. Hormones and Behavior, 59(5), 772–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, A., Nash, M., & Lynch, A. M. (2010). Antidepressant-associated sexual dysfunction: Impact, effects, and treatment. Drug, Healthcare and Patient Safety, 2, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, C. A. (2016). Implicit and explicit sexual motives as related, but distinct characteristics. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 38(2), 59–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinzmann, J., Khalaidovski, K., Kullmann, J. S., Brummer, J., Braun, S., Kurz, P., Wagner, K. M., & Schultheiss, O. C. (2023). Developing a causally valid picture-story measure of sexual motivation: I. Effects of priming. Motivation Science, 9(3), 157–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hisasue, S. I., Kumamoto, Y., Sato, Y., Masumori, N., Horita, H., Kato, R., Kobayashi, K., Hashimoto, K., Yamashita, N., & Itoh, N. (2005). Prevalence of female sexual dysfunction symptoms and its relationship to quality of life: A Japanese female cohort study. Urology, 65(1), 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, H., Janssen, E., & Turner, S. L. (2004). Classical conditioning of sexual arousal in women and men: Effects of varying awareness and biological relevance of the conditioned stimulus. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 33(1), 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y. Y., Peng, D. W., Liu, Q. S., Jiang, H., & Zhang, X. S. (2023). Aerobic exercise improves ejaculatory behaviors and complements dapoxetine treatment by upregulating the BDNF-5-HT duo: A pilot study in rats. Asian Journal of Andrology, 25(5), 637–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubscher, C. H., & Johnson, R. D. (1996). Responses of medullary reticular formation neurons to input from the male genitalia. Journal of Neurophysiology, 76(4), 2474–2482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hueletl-Soto, M. E., Carro-Juárez, M., & Rodríguez-Manzo, G. (2012). Fluoxetine chronic treatment inhibits male rat sexual behavior by affecting both copulatory behavior and the genital motor pattern of ejaculation. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 9(4), 1015–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurd, H. M. (1996). The moral magic of consent. Legal Theory, 2(2), 121–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huston, J. P., Silva, M. A. D., Topic, B., & Muller, C. P. (2013). What’s conditioned in conditioned place preference? Trends in Pharmacological Sciences, 34(3), 162–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janssen, E., & Prause, N. (2016). Sexual response. In J. T. Cacioppo, L. G. Tassinary, & G. G. Berntson (Eds.), Handbook of psychophysiology (4th ed., pp. 284–299). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, E., Everaerd, W., Spiering, M., & Janssen, J. (2000). Automatic processes and the appraisal of sexual stimuli: Toward an information processing model of sexual arousal. Journal of Sex Research, 37(1), 8–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, P. K. C., & Waldinger, M. D. (2016). The mathematical formula of the intravaginal ejaculation latency time (IELT) distribution of lifelong premature ejaculation differs from the IELT distribution formula of men in the general male population. Investigative and Clinical Urology, 57(2), 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayne, C., Clayton, A. H., Jacobs, M., Kimura, T., Lewis-D’Agostino, D., & Pyke, R. (2010). Results from the DAHLIA (511.70) trial: A prospectve, study of flibanserin for the treatment of hypoactive sexual desire disorder in North American premenopausal women. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 7, 48. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, R. D., & Murray, F. T. (1992). Reduced sensitivity of penile mechanoreceptors in aging rats with sexual dysfunction. Brain Research Bulletin, 28(1), 61–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamrul-Hasan, A. B. M., Hannan, M. A., Alam, M. S., Aalpona, F. T. Z., Nagendra, L., Selim, S., & Dutta, D. (2024). Role of flibanserin in managing hypoactive sexual desire disorder in women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine, 103(25), e38592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashdan, T. B., Goodman, F. R., Stiksma, M., Milius, C. R., & McKnight, P. E. (2018). Sexuality leads to boosts in mood and meaning in life with no evidence for the reverse direction: A daily diary investigation. Emotion, 18(4), 563–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaspersen, H., & Ågmo, A. (2012). Paroxetine-induced reduction of sexual incentive motivation in female rats is not modified by 5-HT1B or 5-HT2C antagonists. Psychopharmacology, 220(2), 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, M., DeRogatis, L. R., Ackerman, R., Hedges, P., Lesko, L., Garcia, M., Jr., & Sand, M. (2013). Efficacy of flibanserin in women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder: Results from the BEGONIA trial. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 10(7), 1807–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kihlstrom, J. F. (2019). The motivational unconscious. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 13(5), e12466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingsberg, S. A., & Althof, S. E. (2011). Satisfying sexual events as outcome measures in clinical trial of female sexual dysfunction. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 8(12), 3262–3270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingsberg, S. A., Clayton, A. H., Portman, D., Krop, J., Jordan, R., Lucas, J., & Simon, J. A. (2021). Failure of a meta-analysis: A commentary on Glen Spielmans’s “Re-analyzing phase III bremelanotide trials for ‘hypoactive sexual desire disorder in women’”. Journal of Sex Research, 58(9), 1106–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingsberg, S. A., Clayton, A. H., Portman, D., Williams, L. A., Krop, J., Jordan, R., Lucas, J., & Simon, J. A. (2019). Bremelanotide for the treatment of hypoactive sexual desire disorder: Two randomized phase 3 trials. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 134(5), 899–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinsey, A. C., Pomeroy, W. B., Martin, C. E., & Gebhard, P. H. (1953). Sexual behavior in the human female. Saunders. [Google Scholar]

- Kitchell, R. L., Gilanpour, H., & Johnson, R. D. (1982). Electrophysiological studies of penile mechanoreceptors in the rat. Experimental Neurology, 75(1), 229–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Köllner, M. G., & Schultheiss, O. C. (2014). Meta-analytic evidence of low convergence between implicit and explicit measures of the needs for achievement, affiliation, and power. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laan, E., & Everaerd, W. (1995). Determinants of female sexual arousal: Psychophysiological theory and data. Annual Review of Sex Research, 6(1), 32–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laan, E., & Janssen, E. (2007). How do men and women feel? Determinants of subjective experience of sexual arousal. In E. Janssen (Ed.), The psychophysiology of sex (pp. 278–290). Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lam, R. M., von Buchholtz, L. J., Falgairolle, M., Osborne, J., Frangos, E., Servin-Vences, M. R., Nagel, M., Nguyen, M. Q., Jayabalan, M., Saade, D., Patapoutian, A., Bönnemann, C. G., Ryba, N. J. P., & Chesler, A. T. (2023). PIEZO2 and perineal mechanosensation are essential for sexual function. Science, 381(6660), 906–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, J. W. B. (2014). A dynamic thurstonian item response theory of motive expression in the picture story exercise: Solving the internal consistency paradox of the PSE. Psychological Review, 121(3), 481–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Moëne, O., & Ågmo, A. (2018). The neuroendocrinology of sexual attraction. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology, 51, 46–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Moëne, O., & Ågmo, A. (2019). Modeling human sexual motivation in rodents: Some caveats. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 13, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Moëne, O., Hernández-Arteaga, E., Chu, X., & Ågmo, A. (2020). Rapid changes in sociosexual behaviors around transition to and from behavioral estrus, in female rats housed in a seminatural environment. Behavioural Processes, 174, 104101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leonhardt, N. D., Willoughby, B. J., Busby, D. M., Yorgason, J. B., & Holmes, E. K. (2018). The significance of the female orgasm: A nationally representative, dyadic study of newlyweds’ orgasm experience. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 15(8), 1140–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levin, R. J., & van Berlo, W. (2004). Sexual arousal and orgasm in subjects who experience forced or non-consensual sexual stimulation—A review. Journal of Clinical Forensic Medicine, 11(2), 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, R., Boso Perez, R., Maxwell, K. J., Reid, D., Macdowall, W., Bonell, C., Fortenberry, J. D., Mercer, C. H., Sonnenberg, P., & Mitchell, K. R. (2024). Conceptualizing sexual wellbeing: A qualitative investigation to inform development of a measure (Natsal-SW). Journal of Sex Research, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, L. S., & Nieto, M. A. P. (2023). A motivational approach to sexual desire: A model for self-regulation. International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy, 23(3), 241–259. [Google Scholar]

- Maczkowiack, J., & Schweitzer, R. D. (2019). Postcoital dysphoria: Prevalence and correlates among males. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 45(2), 128–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maswood, N., Sarkar, J., & Uphouse, L. (2008). Modest effects of repeated fluoxetine on estrous cyclicity and sexual behavior in Sprague Dawley female rats. Brain Research, 1245, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matuszczyk, J., Larsson, K., & Eriksson, E. (1998). The selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor fluoxetine reduces sexual motivation in male rats. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior, 60(2), 527–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAuliffe, T. L., DiFranceisco, W., & Reed, B. R. (2007). Effects of question format and collection mode on the accuracy of retrospective surveys of health risk behavior: A comparison with daily sexual activity diaries. Health Psychology, 26(1), 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClelland, D. C., Koestner, R., & Weinberger, J. (1989). How do self-attributed and implicit motives differ? Psychological Review, 96(4), 690–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrae, R. R., Kurtz, J. E., Yamagata, S., & Terracciano, A. (2011). Internal consistency, retest reliability, and their implications for personality scale validity. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 15(1), 28–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meston, C. M., & Worcel, M. (2002). The effects of yohimbine plus L-arginine glutamate on sexual arousal in postmenopausal women with sexual arousal disorder. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 31(4), 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mestre-Bach, G., Blycker, G. R., & Potenza, M. N. (2022). Behavioral therapies for treating female sexual dysfunctions: A state-of-the-art review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 11(10), 2794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyerson, B. J., & Lindström, L. H. (1973). Sexual motivation in the female rat. A methodological study applied to the investigation of the effect of estradiol benzoate. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica Supplementum, 389, 1–80. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Milani, S., Brotto, L. A., & Kingstone, A. (2019). “I can see you”: The impact of implied social presence on visual attention to erotic and neutral stimuli in men and women. Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 28(2), 105–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, K. R., Lewis, R., O’Sullivan, L. F., & Fortenberry, J. D. (2021). What is sexual wellbeing and why does it matter for public health? Lancet Public Health, 6(8), E608–E613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modi, N. B., Dresser, M. J., Simon, M., Lin, D., Desai, D., & Gupta, S. (2006). Single- and multiple-dose pharmacokinetics of dapoxetine hydrochloride, a novel agent for the treatment of premature ejaculation. Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 46(3), 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondaini, N., Fusco, F., Cai, T., Benemei, S., Mirone, V., & Bartoletti, R. (2013). Dapoxetine treatment in patients with lifelong premature ejaculation: The reasons of a “Waterloo”. Urology, 82(3), 620–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, C. D., & Murray, H. A. (1935). A method for investigating fantasies: The thematic apperception test. Archives of Neurology and Psychiatry, 34(2), 289–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nappi, R., Dean, J., van Lunsen, R., Hebert, A., Kimura, T., & Pyke, R. (2009). Efficacy of flibanserin as a potential treatment for hypoactive sexual desire disorder in European premenopausal women: Results from the ORCHID trial. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 6(Suppl. S5), 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neijenhuijs, K. I., Hooghiemstra, N., Holtmaat, K., Aaronson, N. K., Groenvold, M., Holzner, B., Terwee, C. B., Cuijpers, P., & Verdonck-de Leeuw, I. M. (2019). The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI)—A systematic review of measurement properties. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 16(5), 640–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, A. H., Runge, J. M., Ganesan, A. V., Lövenstierne, C., Soni, N., & Kjell, O. N. E. (2025). Automatic implicit motive codings are at least as accurate as humans’ and 99% faster. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimbi, F. M., Tripodi, F., Rossi, R., Navarro-Cremades, F., & Simonelli, C. (2020). Male sexual desire: An overview of biological, psychological, sexual, relational, and cultural factors influencing desire. Sexual Medicine Reviews, 8(1), 59–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nisbett, R. E., & Wilson, T. D. (1977). Telling more than we can know: Verbal reports on mental processes. Psychological Review, 84(3), 231–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oei, N. Y. L., Both, S., van Heemst, D., & van der Grond, J. (2014). Acute stress-induced cortisol elevations mediate reward system activity during subconscious processing of sexual stimuli. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 39, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oei, N. Y. L., Rombouts, S. A. R. B., Soeter, R. P., Van Gerven, J. M., & Both, S. (2012). Dopamine modulates reward system activity during subconscious processing of sexual stimuli. Neuropsychopharmacology, 37(7), 1729–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palumbo, F., Bettocchi, C., Selvaggi, F. P., Pryor, J. P., & Ralph, D. J. (2001). Sildenafil: Efficacy and safety in daily clinical experience. European Urology, 40(2), 176–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, J. S., & Ring, H. (2020). Automated coding of implicit motives: A machine-learning approach. Motivation and Emotion, 44(4), 549–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H. J., Park, N. C., Kim, T. N., Baek, S. R., Lee, K. M., & Choe, S. (2017). Discontinuation of dapoxetine treatment in patients with premature ejaculation: A 2-year prospective observational study. Sexual Medicine, 5(2), e99–e105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfaff, D. W., & Lewis, C. (1974). Film analyses of lordosis in female rats. Hormones and Behavior, 5(4), 317–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfaus, J., Giuliano, F., & Gelez, H. (2007). Bremelanotide: An overview of preclinical CNS effects on female sexual function. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 4(s4), 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfaus, J. G. (2022). Politics of sexual desire. Current Sexual Health Reports, 14(3), 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfaus, J. G., Shadiack, A., van Soest, T., Tse, M., & Molinoff, P. (2004). Selective facilitation of sexual solicitation in the female rat by a melanocortin receptor agonist. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 101(27), 10201–10204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzol, D., López Sánchez, G. F., Ilie, P. C., Bertoldo, A., Trott, M., Tully, M. A., Wilson, J. J., Veronese, N., Soysal, P., Carrie, A., Ippoliti, S., Pratsides, L., Shah, S., Koyanagi, A., Butler, L., Barnett, Y., Parris, C. R., Lindsay, R., & Smith, L. (2023). Non-pharmacological approaches for treatment of premature ejaculation: A systematic review. Trends in Urology & Men’s Health, 14(2), 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pransky, G., Finkelstein, S., Berndt, E., Kyle, M., Mackell, J., & Tortorice, D. (2006). Objective and self-report work performance measures: A comparative analysis. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 55(5), 390–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prince, S. A., Adamo, K. B., Hamel, M. E., Hardt, J., Gorber, S. C., & Tremblay, M. (2008). A comparison of direct versus self-report measures for assessing physical activity in adults: A systematic review. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 5, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pyke, R., & Clayton, A. (2016). What sexual behaviors relate to decreased sexual desire in women? A review and proposal for end points in treatment trials for hypoactive sexual desire disorder. Sexual Medicine, 5(2), e73–e83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pyke, R. E., & Clayton, A. H. (2018). Effect size in efficacy trials of women with decreased sexual desire. Sexual Medicine Reviews, 6(3), 358–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramjee, G., Weber, A. E., & Morar, N. S. (1999). Recording sexual behavior: Comparison of recall questionnaires with a coital diary. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 26(7), 374–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez Aranda, L. E., & Ågmo, A. (2023). La respuesta genital a incentivos sexuales: Una ventana abierta de par en par al ello. In M. Hernández González, A. C. Medina Fragoso, & M. A. Guevara Pérez (Eds.), Psicobiología de la activación sexual (pp. 23–59). Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen, R., Brown, C., Heiman, J., Leiblum, S., Meston, C., Shabsigh, R., Ferguson, D., & D’Agostino, R. (2000). The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): A multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 26(2), 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, R. C., Lane, R. M., & Menza, M. (1999). Effects of SSRIs on sexual function: A critical review. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 19(1), 67–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, N. A., & Reid, L. D. (1976). Affective states associated with morphine injections. Physiological Psychology, 4(3), 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowland, D. L., Kallan, K., & Slob, A. K. (1997). Yohimbine, erectile capacity, and sexual response in men. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 26(1), 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sand, M., Thorp, J., Simon, J., Dattani, D., Taylor, L., Lesko, L., Kimura, T., & Pyke, R. (2010). Efficacy of flibanserin in North American premenopausal women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder: Results from the DAISY trial. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 7(Suppl. S1), 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarin, S., Amsel, R., & Binik, Y. M. (2014). How hot is he? A psychophysiological and psychosocial examination of the arousal patterns of sexually functional and dysfunctional men. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 11(7), 1725–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarin, S., Amsel, R., & Binik, Y. M. (2016). A streetcar named “derousal”? A psychophysiological examination of the desire-arousal distinction in sexually functional and dysfunctional women. Journal of Sex Research, 53(6), 711–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schultheiss, O. C., & Hinzmann, J. C. (2025). Developing a measure for the need for sex. In O. C. Schultheiss, & J. S. Pang (Eds.), Implicit motives (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. in press. [Google Scholar]

- Schultheiss, O. C., Hinzmann, J., Bergmann, S., Matthes, M., Beyer, B., & Janson, K. T. (2023). Developing a causally valid picture-story measure of sexual motivation: II. Effects of film clips. Motivation Science, 9(4), 272–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultheiss, O. C., & Köllner, M. G. (2021). Implicit motives. In O. P. John, & R. W. Robbins (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (4th ed., pp. 385–410). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schultheiss, O. C., Liening, S. H., & Schad, D. (2008). The reliability of a Picture Story Exercise measure of implicit motives: Estimates of internal consistency, retest reliability, and ipsative stability. Journal of Research in Personality, 42(6), 1560–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultheiss, O. C., Yankova, D., Dirlikov, B., & Schad, D. J. (2009). Are implicit and explicit motive measures statistically independent? A fair and balanced test using the picture story exercise and a cue- and response-matched questionnaire measure. Journal of Personality Assessment, 91(1), 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweitzer, R. D., O’Brien, J., & Burri, A. (2015). Postcoital dysphoria: Prevalence and psychological correlates. Sexual Medicine, 3(4), 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafik, A., Shafik, A. A., El Sibai, O., & Shafik, I. A. (2009). Electromyographic study of ejaculatory mechanism. International Journal of Andrology, 32(3), 212–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, J. A., Clayton, A. H., Kim, N. N., & Patel, S. (2022). Clinically meaningful benefit in women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder treated with flibanserin. Sexual Medicine, 10(1), 100476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavin, M. N., Scoglio, A. A. J., Blycker, G. R., Potenza, M. N., & Kraus, S. W. (2020). Child sexual abuse and compulsive sexual behavior: A systematic literature review. Current Addiction Reports, 7(1), 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snoeren, E. M. S., Chan, J. S. W., de Jong, T. R., Waldinger, M. D., Olivier, B., & Oosting, R. S. (2011a). A new female rat animal model for hypoactive sexual desire disorder; Behavioral and pharmacological evidence. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 8(1), 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snoeren, E. M. S., Refsgaard, L. K., Waldinger, M. D., Olivier, B., & Oosting, R. S. (2011b). Chronic paroxetine treatment does not affect sexual behavior in hormonally sub-primed female rats despite 5-HT1A receptor desensitization. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 8(4), 976–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spielmans, G. I. (2021). Re-analyzing phase III bremelanotide trials for “hypoactive sexual desire disorder” in women. Journal of Sex Research, 58(9), 1085–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spielmans, G. I., & Ellefson, E. M. (2024). Small effects, questionable outcomes: Bremelanotide for hypoactive sexual desire disorder. Journal of Sex Research, 61(4), 540–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, S. M. (2015). Mechanism of action of flibanserin, a multifunctional serotonin agonist and antagonist (MSAA), in hypoactive sexual desire disorder. CNS Spectrums, 20(1), 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, S. M., Sommer, B., & Allers, K. A. (2011). Multifunctional pharmacology of flibanserin: Possible mechanism of therapeutic action in hypoactive sexual desire disorder. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 8(1), 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, K. R., Pickworth, C., & Jones, P. S. (2024). Gender differences in the association between sexual satisfaction and quality of life. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 39(2), 301–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoléru, S., Fonteille, V., Cornelis, C., Joyal, C., & Moulier, V. (2012). Functional neuroimaging studies of sexual arousal and orgasm in healthy men and women: A review and meta-analysis. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 36(6), 1481–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajkarimi, K., & Burnett, A. L. (2011). The role of genital nerve afferents in the physiology of the sexual response and pelvic floor function. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 8(5), 1299–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, S. W., Worcel, M., & Wyllie, M. (2001). Yohimbine: A clinical review. Pharmacology and Therapeutics, 91(3), 215–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorp, J., Simon, J., Dattani, D., Taylor, L., Lesko, L., Kimura, T., & Pyke, R. (2009). Efficacy of flibanserin as a potential treatment for Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder in North American premenopausal women: Results from the DAISY trial. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 6, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toates, F. (2009). An integrative theoretical framework for understanding sexual motivation, arousal, and behavior. Journal of Sex Research, 46(2–3), 168–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toates, F. (2022). A motivation model of sex addiction—Relevance to the controversy over the concept. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 142, 104872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Touraille, P., & Ågmo, A. (2024). Sex differences in sexual motivation in humans and other mammals: The role of conscious and unconscious processes. Behavioral Sciences, 14(4), 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turley, E. L., & Butt, T. (2015). BDSM—Bondage and discipline; dominance and submission; sadism and masochism. In C. Richards, & M. J. Barker (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of the psychology of sexuality and gender (pp. 24–41). Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uphouse, L., Pinkston, J., Baade, D., Solano, C., & Onaiwu, B. (2015). Use of an operant paradigm for the study of antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction. Behavioural Pharmacology, 26(7), 697–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura-Aquino, E., & Ågmo, A. (2023). The elusive concept of sexual motivation: Can it be anchored in the nervous system? Frontiers in Neuroscience, 17, 1285810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura-Aquino, E., & Paredes, R. G. (2017). Animal models in sexual medicine: The need and importance of studying sexual motivation. Sexual Medicine Reviews, 5(1), 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura-Aquino, E., Portillo, W., & Paredes, R. G. (2018). Sexual motivation: A comparative approach in vertebrate species. Current Sexual Health Reports, 10(3), 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergauwen, K., Huijnen, I. P. J., Smeets, R. J. E. M., Kos, D., van Eupen, I., Nijs, J., & Meeus, M. (2021). An exploratory study of discrepancies between objective and subjective measurement of the physical activity level in female patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 144, 110417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viitamaa, T., Haapalinna, A., & Ågmo, A. (2006). The adrenergic a2 receptor and sexual incentive motivation in male rats. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior, 83, 360–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wac, K. (2009). Healthcare to go: The MobilHealth system. Engineering and Technology, 4(17), 62–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallis, R. M., Corbin, J. D., Francis, S. H., & Ellis, P. (1999). Tissue distribution of phosphodiesterase families and the effects of sildenafil on tissue cyclic nucleotides, platelet function, and the contractile responses of trabeculae carneae and aortic rings in vitro. American Journal of Cardiology, 83(5, Suppl. S1), 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, M. (2013). “On Lucretia who slew herself”: Rape and Consolation in Augustine’s De ciuitate dei. Augustinian Studies, 44(1), 37–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westen, D. (1998). Unconscious thought, feeling, and motivation: The end of a century-long debate. In R. F. Bronstein, & J. M. Masling (Eds.), Empirical perspectives on the psychoanalytic unconscious (pp. 1–43). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westra, E., Fitzpatrick, S., Brosnan, S. F., Gruber, T., Hobaiter, C., Hopper, L. M., Kelly, D., Krupenye, C., Luncz, L. V., Theriault, J., & Andrews, K. (2024). In search of animal normativity: A framework for studying social norms in non-human animals. Biological Reviews, 99(3), 1058–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiederman, M. W. (2015). Sexual script theory: Past, present, and future. In J. D. DeLamater, & R. F. Plante (Eds.), Handbook of the sociology of sexualities (pp. 7–22). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. (2024). Clinical descriptions and diagnostic requirements for ICD-11 mental, behavioural and neurodevelopmental disorders. World Heaslth Organization. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/375767/9789240077263-eng.pdf (accessed on 17 November 2024).

- Yang, C. C., & Bradley, W. E. (2000). Reflex innervation of the bulbocavernosus muscle. BJU International, 85(7), 857–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yates, J. R. (2023). Quantifying conditioned place preference: A review of current analyses and a proposal for a novel approach. Frontiers in Behavioral Neurosciience, 17, 1256764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, M. D. (2024). Automated motive scoring and international crisis behavior. Foreign Policy Analysis, 20(2), orae001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X. C., & Tao, Y. X. (2022). Ligands for melanocortin receptors: Beyond melanocyte-stimulating hormones and adrenocorticotropin. Biomolecules, 12(10), 1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, T., Gao, P., Gao, J., Liu, X., Jiang, H., & Zhang, X. (2022). The upregulation of tryptophan hydroxylase-2 expression is important for premature ejaculation treatment with the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor. Andrology, 10(3), 595–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Drug | Test | Effect Rat | Clinical Effect Human |

|---|---|---|---|

| Paroxetine a | Paced mating | None 1 | Enhanced incidence of sexual dysfunctions including reduced motivation 2 |

| Sexual approach | Reduced 3 | ||

| Fluoxetine b | Copulatory behavior | None 4 or enhanced ejaculation latency 5 reduced lordosis 6 | Enhanced incidence of sexual dysfunctions perhaps even reduced motivation 7 |

| Sexual approach | Reduced 8 | ||

| Yohimbine b | Sexual approach | Enhanced 9 | Possibly increased sexual motivation 10 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ågmo, A. Sexual Motivation (Desire): Problems with Current Preclinical and Clinical Evaluations of Treatment Effects and a Solution. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 642. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050642

Ågmo A. Sexual Motivation (Desire): Problems with Current Preclinical and Clinical Evaluations of Treatment Effects and a Solution. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(5):642. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050642

Chicago/Turabian StyleÅgmo, Anders. 2025. "Sexual Motivation (Desire): Problems with Current Preclinical and Clinical Evaluations of Treatment Effects and a Solution" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 5: 642. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050642

APA StyleÅgmo, A. (2025). Sexual Motivation (Desire): Problems with Current Preclinical and Clinical Evaluations of Treatment Effects and a Solution. Behavioral Sciences, 15(5), 642. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050642