A Review of Additive Manufacturing Studies for Producing Customized Ankle-Foot Orthoses

Abstract

1. Introduction

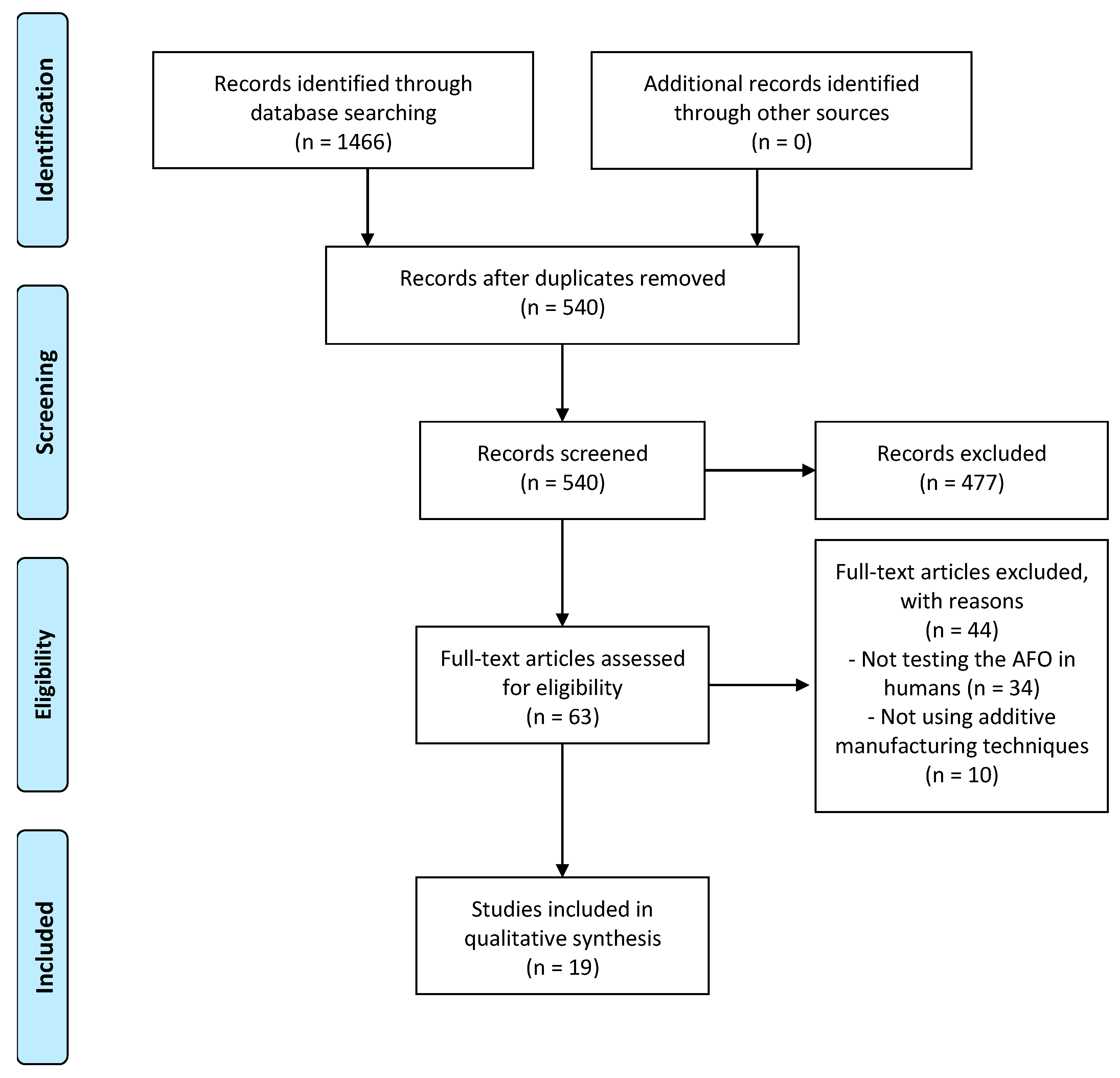

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Inman, V.T.; Ralston, H.J.; Todd, F. Human Walking; Williams & Wilkins: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1981; ISBN 068304348X. [Google Scholar]

- Hayek, S.; Hemo, Y.; Chamis, S.; Bat, R.; Segev, E.; Wientroub, S.; Yzhar, Z. The effect of community-prescribed ankle-foot orthoses on gait parameters in children with spastic cerebral palsy. J. Child. Orthop. 2007, 1, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wren, T.A.L.; Dryden, J.W.; Mueske, N.M.; Dennis, S.W.; Healy, B.S.; Rethlefsen, S.A. Comparison of 2 Orthotic Approaches in Children with Cerebral Palsy. Pediatr. Phys. Ther. 2015, 27, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abd El-Kafy, E.M. The clinical impact of orthotic correction of lower limb rotational deformities in children with cerebral palsy: A randomized controlled trial. Clin. Rehabil. 2014, 28, 1004–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, B.C.; Russell, S.D.; Abel, M.F. The effects of ankle foot orthoses on energy recovery and work during gait in children with cerebral palsy. Clin. Biomech. 2012, 27, 287–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brehm, M.A.; Harlaar, J.; Schwartz, M. Effect of ankle-foot orthoses on walking efficiency and gait in children with cerebral palsy. J. Rehabil. Med. 2008, 40, 529–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginosian, J.; Kluding, P.M.; McBride, K.; Feld, J.; Wu, S.S.; O’Dell, M.W.; Dunning, K. Foot Drop Stimulation versus Ankle Foot Orthosis after Stroke. Stroke 2013, 44, 1660–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaaret, I.; Steen, H.; Terjesen, T.; Holm, I. Impact of ankle-foot orthoses on gait 1 year after lower limb surgery in children with bilateral cerebral palsy. Prosthet. Orthot. Int. 2019, 43, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, T.; Singer, M.L.; Orendurff, M.S.; Gao, F.; Daly, W.K.; Foreman, K.B. The effect of changing plantarflexion resistive moment of an articulated ankle-foot orthosis on ankle and knee joint angles and moments while walking in patients post stroke. Clin. Biomech. 2015, 30, 775–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machat, H.; Mazaux, J.M.; de Sèze, M.-P.; Rousseaux, M.; Daviet, J.-C.; Bonhomme, C.; Burguete, E. Effect of early compensation of distal motor deficiency by the Chignon ankle-foot orthosis on gait in hemiplegic patients: A randomized pilot study. Clin. Rehabil. 2011, 25, 989–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gronely, J.K.; Weiss, W.; Newsam, C.J.; Mulroy, S.J.; Eberly, V.J. Effect of AFO Design on Walking after Stroke: Impact of Ankle Plantar Flexion Contracture. Prosthet. Orthot. Int. 2010, 34, 277–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Totah, D.; Kovalenko, I.; Saez, M.; Barton, K. Manufacturing Choices for Ankle-Foot Orthoses: A Multi-objective Optimization. Procedia CIRP 2017, 65, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.K.; Jin, Y.-A.; Wensman, J.; Shih, A. Additive manufacturing of custom orthoses and prostheses—A review. Addit. Manuf. 2016, 12, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morouço, P. The Usefulness of Direct Digital Manufacturing for Biomedical Applications. Green Chem. Ser. 2018, 55, 478–487. [Google Scholar]

- Cha, Y.H.; Lee, K.H.; Ryu, H.J.; Joo, I.W.; Seo, A.; Kim, D.H.; Kim, S.J. Ankle-foot orthosis made by 3D printing technique and automated design software. Appl. Bionics Biomech. 2017, 2017, 9610468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olsson, A.; Hellsing, M.S.; Rennie, A.R. New possibilities using additive manufacturing with materials that are difficult to process and with complex structures. Phys. Scr. 2017, 92, 53002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balshem, H.; Helfand, M.; Schünemann, H.J.; Oxman, A.D.; Kunz, R.; Brozek, J.; Vist, G.E.; Falck-Ytter, Y.; Meerpohl, J.; Norris, S. GRADE guidelines: 3. Rating the quality of evidence. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2011, 64, 401–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 89, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dal Maso, A.; Cosmi, F. 3D-printed ankle-foot orthosis: A design method. Mater. Today Proc. 2019, 12, 252–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belokar, R.M.; Banga, H.K.; Kumar, R. A Novel Approach for Ankle Foot Orthosis Developed by Three Dimensional Technologies. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2017, 280, 12030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.K.; Chen, L.; Tai, B.L.; Wang, Y.; Shih, A.J.; Wensman, J. Additive manufacturing of personalized ankle-foot orthosis. Trans. N. Am. Manuf. Res. Inst. SME 2014, 42, 381–389. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, P.; Yan, M.; Xie, Y.; Huang, G. Additive manufacturing of specific ankle-foot orthoses for persons after stroke: A preliminary study based on gait analysis data. Math. Biosci. Eng. 2019, 16, 8134–8143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarma, T.; Pandey, D.; Sahai, N.; Tewari, R.P. Material selection and development of ankle foot orthotic device. Mater. Today Proc. 2019, 18, 2509–2514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patar, A.; Jamlus, N.; Makhtar, K.; Mahmud, J.; Komeda, T. Development of dynamic ankle foot orthosis for therapeutic application. Procedia Eng. 2012, 41, 1432–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Schrank, E.S.; Stanhope, S.J. Dimensional accuracy of ankle-foot orthoses constructed by rapid customization and manufacturing framework. J. Rehabil. Res. Dev. 2011, 48, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavroidis, C.; Ranky, R.G.; Sivak, M.L.; Patritti, B.L.; DiPisa, J.; Caddle, A.; Gilhooly, K.; Govoni, L.; Sivak, S.; Lancia, M.; et al. Patient specific ankle-foot orthoses using rapid prototyping. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2011, 8, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wierzbicka, N.; Górski, F.; Wichniarek, R.; Kuczko, W. Prototyping of Individual Ankle Orthosis Using Additive Manufacturing Technologies. Adv. Sci. Technol. Res. J. 2017, 11, 283–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, D.-S.; Kim, D.-H.; Kang, K.-Y.; Kim, D.-Y.; Park, S.-W.; Park, S.-J.; Kim, J.-H. The functional effect of 3D-printing individualized orthosis for patients with peripheral nerve injuries: Three case reports. Medicine 2020, 99, e19791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creylman, V.; Muraru, L.; Pallari, J.; Vertommen, H.; Peeraer, L. Gait assessment during the initial fitting of customized selective laser sintering ankle foot orthoses in subjects with drop foot. Prosthet. Orthot. Int. 2013, 37, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, N.G.; Esposito, E.R.; Wilken, J.M.; Neptune, R.R. The influence of ankle-foot orthosis stiffness on walking performance in individuals with lower-limb impairments. Clin. Biomech. 2014, 29, 877–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasiliauskaite, E.; Ielapi, A.; De Beule, M.; Van Paepegem, W.; Deckers, J.P.; Vermandel, M.; Forward, M.; Plasschaert, F. A study on the efficacy of AFO stiffness prescriptions. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2019, 16, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telfer, S.; Pallari, J.; Munguia, J.; Dalgarno, K.; McGeough, M.; Woodburn, J. Embracing additive manufacture: Implications for foot and ankle orthosis design. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2012, 13, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.-C.; Lin, K.-W.; Chen, C.-S. Evaluation of the walking performance between 3D-printed and traditional fabricated ankle-foot orthoses—A prospective study. Gait Posture 2017, 57, 366–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.; Peters, K.M.; MacConnell, M.B.; Ly, K.K.; Eckert, E.S.; Steele, K.M. Impact of ankle foot orthosis stiffness on Achilles tendon and gastrocnemius function during unimpaired gait. J. Biomech. 2017, 64, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranz, E.C.; Esposito, E.R.; Wilken, J.M.; Neptune, R.R. The influence of passive-dynamic ankle-foot orthosis bending axis location on gait performance in individuals with lower-limb impairments. Clin. Biomech. 2016, 37, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deckers, J.P.; Vermandel, M.; Geldhof, J.; Vasiliauskaite, E.; Forward, M.; Plasschaert, F. Development and clinical evaluation of laser-sintered ankle foot orthoses. Plast. Rubber Compos. 2018, 47, 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melchels, F.P.W.; Feijen, J.; Grijpma, D.W. A review on stereolithography and its applications in biomedical engineering. Biomaterials 2010, 31, 6121–6130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, K.V.; Hernandez, A. A review of additive manufacturing. Int. Sch. Res. Not. 2012, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.-H.; Chiu, M.-L.; Yen, H.-C. Slurry-based selective laser sintering of polymer-coated ceramic powders to fabricate high strength alumina parts. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2011, 31, 1383–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, T.D.; Kashani, A.; Imbalzano, G.; Nguyen, K.T.Q.; Hui, D. Additive manufacturing (3D printing): A review of materials, methods, applications and challenges. Compos. Part B Eng. 2018, 143, 172–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gök, H.; Küçükdeveci, A.; Altinkaynak, H.; Yavuzer, G.; Ergin, S. Effects of ankle-foot orthoses on hemiparetic gait. Clin. Rehabil. 2003, 17, 137–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesikburun, S.; Yavuz, F.; Güzelküçük, Ü.; Yaşar, E.; Balaban, B. Effect of ankle foot orthosis on gait parameters and functional ambulation in patients with stroke. Turkiye Fiz. Tip Rehabil. Derg. 2017, 63, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Linden, M.L.; Andreopoulou, G.; Scopes, J.; Hooper, J.E.; Mercer, T.H. Ankle kinematics and temporal gait characteristics over the duration of a 6-minute walk test in people with multiple sclerosis who experience foot Drop. Rehabil. Res. Pract. 2018, 2018, 1260852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prosser, L.A.; Curatalo, L.A.; Alter, K.E.; Damiano, D.L. Acceptability and potential effectiveness of a foot drop stimulator in children and adolescents with cerebral palsy. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2012, 54, 1044–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ries, A.J.; Novacheck, T.F.; Schwartz, M.H. The Efficacy of Ankle-Foot Orthoses on Improving the Gait of Children with Diplegic Cerebral Palsy: A Multiple Outcome Analysis. PM R. 2015, 7, 922–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carolus, A.E.; Becker, M.; Cuny, J.; Smektala, R.; Schmieder, K.; Brenke, C. The interdisciplinary management of foot drop. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2019, 116, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuccarino, R.; Anderson, K.M.; Shy, M.E.; Wilken, J.M. Satisfaction with Ankle Foot Orthoses in Individuals with Charcot-Marie-Tooth. Muscle Nerve 2021, 63, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arazpour, M.; Tajik, H.R.; Aminian, G.; Bani, M.A.; Ghomshe, F.T.; Hutchins, S.W. Comparison of the effects of solid versus hinged ankle foot orthoses on select temporal gait parameters in patients with incomplete spinal cord injury during treadmill walking. Prosthet. Orthot. Int. 2013, 37, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townsend, E.L.; Tamhane, H.; Gross, K.D. Effects of AFO Use on Walking in Boys with Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy: A Pilot Study. Pediatr. Phys. Ther. 2015, 27, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtkamp, F.C.; Wouters, E.J.M.; Van Hoof, J.; van Zaalen, Y.; Verkerk, M.J. Use of and satisfaction with ankle foot orthoses. Clin. Res. Foot Ankle 2015, 2, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Mueller, B. Additive manufacturing technologies–Rapid prototyping to direct digital manufacturing. Assem. Autom. 2012, 32, 400–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reference | AFO Details | Participant/Patient Characteristics | Intervention vs. Control Condition | Outcomes | Main Results and Conclusions | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AM Printing Method | Material | N | Condition | ||||

| Belokar, Banga and Kumar, 2017 [20] | FDM | ABS | 1 (M; 65 kg) | Healthy | Customized ABS AFO | Mechanical test | Maximum 6.8% strain with 38.4 MPa tensile strength exerted on the AFO. Rupture of the AFO at 14.96 kJ/m2 impact. No deformation in the inner surface with load up to 15 kN. No deformation of the AFO in hydraulic press test with 10 tons load. |

| Cha et al., 2017 [15] | FDM | TPU | 1 (F; 68 years) | Foot drop on the right side after an embolectomy | Customized TPU AFO vs. TTPP AFO vs. Shod Only | Mechanical test; QUEST; kinematics | No structural change, crack or damage after 300k repetitions in the durability test. Both AFO increased gait speed and stride length. Step width decreased with the FDM AFO. Higher bilateral symmetry with FDM AFO induced more stability. Better satisfaction on the FDM AFO after using both AFO for 2 months. |

| Chae et al., 2020 [28] | FDM | TPU | 1 (F; 72 years) | Foot drop on the right side after posterior lumbar interbody fusion and abscess | Customized TPU AFO vs. Without AFO | Kinematics; QUEST | Using the AFO, cardiorespiratory fitness and functionality increased. Stability score with eyes open and closed improved. In QUEST items, the device and service subscore had a perfect score (5 points) showing the patient’s satisfaction with the AFO. |

| Chen et al., 2014 [21] | FDM | ABS; ULTEM (Polyetherimide) | 1 (M; 29 years; 68 kg) | Healthy | Customized ABS AFOs vs. TTPP AFO | Mechanical test; FEM simulations | The highest strains were found at about 50% of the gait cycle for PP (–15.3 × 10−4), ABS (–6.4 × 10−4), and ULTEM (–10.3 × 10−4). The FEM estimated rotational stiffness (N·m/deg) for PP (39.1), ABS (67.7) and ULTEM (89.0). Using calculated loading conditions and FEM can help design AFO to match the patient’s need and achieve desired biomechanical functions. |

| Choi et al., 2017 [34] | FDM | PLA | 8 (4F; 4M; 25 ± 5 years; 1.7 ± 0.1 m; 67 ± 9 Kg) | Healthy | Customized PLA AFO with elastic polymer bands | Kinematics, ultrasound; EMG; musculoskeletal simulation | Use of elastic polymer bands to control the stiffness of the orthosis. More stiffness led to a decrease of peak in knee extension and ankle dorsiflexion angles and maximum length of the gastrocnemius and Achilles tendons. Due to medial gastrocnemius operating length and velocity changes, slower walking speeds may not receive the expected energy savings. |

| Creylman et al., 2013 [29] | SLS | Nylon 12 (PA2201) | 8 (M; 47 ± 13 years; 1.97 ± 0.1m; 85.30 ± 14.20 Kg) | Unilateral Foot Drop due to dorsiflexor weakness | Customized Nylon 12 AFO vs. TTPP AFO vs. Bare Foot | Kinematics | Similar stride duration for all interventions. Significant differences in both AFO vs. barefoot for stride length of the affected (1377 vs. 1370 vs. 1213 mm) and unaffected (1373 vs. 1365 vs. 1223 mm) limb and stance phase duration of the affected limb (62.1 vs. 62.1 vs. 60.6%) for barefoot, AM AFO and TTPP. Range of Motion different between AFO due to Nylon 12 stiffer than PP. |

| Deckers et al., 2018 [36] | SLS | PA12 | 7 (4 Adults; 3 Children) | Trauma, Neuro-muscular disorder and cerebral palsy | Customized PA12 AFO with carbon fiber strut vs. TTPP AFO | Observation after trial | TTPP AFO (n = 7) survived the six weeks of clinical trial. For AM AFO (n = 7), three broke when doing sport, one broke while the patient walked upstairs, one broke due to a manufacturing defect, and one became dirty. A cracking began at the metatarsal phalangeal joint, and one survived with no problems. |

| Harper et al., 2014 [30] | SLS | Nylon 11 (PA D80—S.T.) | 13 (M; 29 ± 6 years; 1.8 ± 0.1 m; 88 ± 11 Kg) | Unilateral lower extremity injuries | Customized Nylon 11 PD-AFO Strut (nominal vs. 20% stiffer vs. more compliant) | Kinematics; kinetics; EMG | Minimal effect in kinetics, kinematics and EMG gait cycle with different strut stiffness. Propulsive and medial GRF impulses were only influenced by AFO stiffness with the medial GRF impulse significantly increased in the stiff condition. Orthotists may not need to control the stiffness level precisely and may instead prescribe the AFO stiffness based on other factors. |

| Lin, Lin, and Chen, 2017 [33] | FDM | No Data | 1 | Healthy | Customized AFO vs. TTPP AFO | Kinematics | The walking speed (367 vs. 389 mm/s), stride length (583 vs. 598 mm), cadence (76 vs. 78 steps/min) and range of motion of knee joint in flexion were similar in both AFO. TTPP AFO obtained more extended range of motion due to different footplate. |

| Liu et al., 2019 [22] | MJF | PA12 | 12 (4F; 8M; 56 ± 9 years; 1.7 ± 0.1 m; 69 ± 10 Kg) | Stroke patients (6 Ischemic, 6 Hemorrhage). | Customized PA12 AFO vs. Without AFO | Mechanical test; kinematics; patient feedback | Using AM AFO increased velocity (0.17 ± 0.06 vs. 0.20 ± 0.07 m/s), stride length (0.43 ± 0.10 vs. 0.48 ± 0.11 m) and cadence (47.0 ± 14.4 vs. 53.8 ± 15.5 times/min). Double limb support phase (36.3 ± 5.6 vs. 33.6 ± 5.2 %) and the step length difference decreased (0.16 ± 0.12 vs. 0.10 ± 0.09 m). AM AFO obtained adequate dimensional accuracy, toughness, high strength, lightweight and comfort. No breakage occurred within three months. |

| Maso and Cosmi, 2019 [19] | FDM | PLA | 1 (F; 21 years) | Post-traumatic rehabilitation | Customized PLA AFO | Mechanical Test; FEM simulations; patient feedback | Great geometrical correspondence and comfort between the foot and the AM AFO. Cheap production method compared with AFO produced with other technologies. PLA material was considered excellent for manufacturing the AFO but is not the most mechanically resistant. |

| Mavroidis et al., 2011 [26] | SLA | Accura 40 Resin; DSM Somos 9120 Epoxy Photopolymer | 1 | Healthy | Customized Accura 40 Resin AFO vs. Customized DSM Somos 9120 Epoxy Photopolymer vs. TTPP AFO vs. Shod only | Kinematics; kinetics; participant feedback | AM AFO obtained optimal fit and great comfort. Kinetics and Kinematics gait cycle revealed that the AM AFO performed similarly to the TTPP AFO. |

| Patar et al., 2012 [24] | FDM | ABS | 1 | Healthy | Customized ABS/PP DAFO (Dynamic Ankle-Foot Orthosis) vs. No control | Participant feedback | The price reduction in producing AM DAFO was reduced 100-fold compared to the products that existed in the market. The patient considered the performance was good. |

| Ranz et al., 2016 [35] | SLS | Nylon 11 (PA D80—S.T.) | 13 (29.50 ± 6.28 years; 1.79 ± 0.09 m; 87.92 ± 9.70 Kg) | Lower extremity trauma resulting in unilateral ankle muscle weakness | Customized Nylon 11 PD-AFO (low vs. middle vs. high bending axis) | Kinematics; Kinetics; EMG | Most of the patients (7) preferred the middle bending axis. After EMG test, PD-AFO altered medial gastrocnemius activity in late single-leg support. Low bending axis resulted in the greatest medial gastrocnemius activity. Different bending axis locations had few effects on ankle and knee peak joint kinematics and kinetics. |

| Sarma et al., 2019 [23] | No data | 13% Kevlar Fiber reinforced ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene (UHMWPE) | >1 | No data | Customized Kevlar Fiber Reinforced UHMWPE AFO | Kinematics; kinetics; FEM simulations | Based on FEM simulations Kevlar Fiber Reinforced UHMWPE-based composite material was selected as best material for fabrication of AFO compared with ABS, PLA, Nylon 6/6 and PP. The maximum ankle angle during dorsiflexion was 12° and maximum angle during plantar flexion was 23°. |

| Schrank and Stanhope, 2011 [25] | SLS | Nylon 11 (DuraForm EX Natural Plastic) | 2 (1 M; 1 F; 34.50 ± 19.09 years; 1.71 ± 8.49 m; 65.85 ± 8.41 Kg) | Healthy | Customized Nylon 11 PD-AFO | Dimensional accuracy; clinical observation; participant feedback | The dimensional accuracy of the fabricated PD-AFOs was 0.5 mm. The participants demonstrated a fully accommodated, smooth, and rhythmic gait pattern following gait test and reported no discomfort. No signs of uneven pressure distribution, redness, or abrasions. |

| Telfer et al., 2012 [32] | SLS | Nylon 12 (PA2200) | 1 (M, 29 years; 1.85 m; 78.00Kg) | Healthy | Customized Nylon 12 AFO with gas spring vs. Shod only | Kinematics; kinetics | Use of a gas spring to control the stiffness of the AFO. AM AFO led to a lower peak plantarflexion angle at the start stance and higher at the toe-off vs. shod only. Peak ankle internal plantarflexion moment was significantly reduced in both AFO conditions compared to shod. Both AFO conditions also increased peak knee internal flexion moment during the first half of stance. AM AFO clinical performance and biomechanical changes equivalent to TTPP AFO with the advantage of the design freedom provided by AM. |

| Vasiliauskaite et al., 2019 [31] | SLS | PA12 | 6 (3M (1 adult, 2 children); 3F (1 adult, 2 children); 23 ± 20 years; 1.5 ± 0.2 m; 52 ± 33 Kg) | 1 poly-trauma; 1 Charcot-Marie Tooth; 3 cerebral palsy; 1 bilateral clubfoot | Customized PA12 AFO with carbon strut vs. TTPP AFO vs. Shod Only | Kinematics; kinetics | AM AFO step length significantly increased vs. TTPP AFO due to better energy storage properties. Push-off phase characteristics and joint work in stance became more atypical using AFO and no significant improvements in speed were observed. |

| Wierzbicka et al., 2017 [27] | FDM | ABS | 1 (F; 22 years) | Chronic ankle joint instability | Customized ABS AFO vs. No control | Observation after trial; patient feedback | The AFO was comfortable and fully stabilizing the ankle joint. After gait cycle the test ended with success without no bruises or irritations on patient’s skin. Limitations were found in climbing stairs, riding a bike, and driving a car. |

| Quality Assessment | Nº of Patients/Participants | Effect | Quality | Importance | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nº of Studies | Study Design | Risk of Bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other Considerations | Customized AM AFO | Traditional Thermoformed Polypropylene AFO | Relative (95% CI) | Absolute (95% CI) | ||

| Walking ability through biomechanical tests (kinematics, kinetics, EMG) | ||||||||||||

| 12 | Observational studies [15,22,23,26,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35] | serious a,b | not serious | Serious a | not serious | none | 66 g | 9 | -- | -- | ⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | Important |

| Durability through a mechanical test | ||||||||||||

| 5 | Observational studies [15,19,20,21,22] | not serious | not serious | serious a,c | serious d | none | 16 | 2 | -- | -- | ⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | Important |

| Durability through observation after trial | ||||||||||||

| 2 | Observational studies [27,36] | very serious e | not serious | not serious | serious d | none | 8 | 7 | -- | -- | ⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | Important |

| Patient satisfaction assessed with the QUEST | ||||||||||||

| 2 | Observational studies [15,28] | serious f | not serious | not serious | serious a,d | none | 2 | 1 | -- | -- | ⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | Important |

| Comfort through participant/patient feedback | ||||||||||||

| 6 | Observational studies [19,22,24,25,26,27] | very serious b,e | not serious | serious a | serious d | none | 17 | 1 | -- | -- | ⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | Important |

| Dimensional accuracy through FaroArm (fit with a 3 mm spherical tip) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | Observational studies [25] | not serious | not serious | serious a | serious d | none | 1 | 0 | -- | -- | ⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | Important |

| Material strength and AFO behavior simulation assessed by FEM analysis | ||||||||||||

| 3 | Observational studies [19,21,23] | serious d | not serious | serious a | serious d | none | 3 | 1 | -- | -- | ⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW | Important |

| Reference | N | Healthy/ Unhealthy | Ankle Dorsiflexion (°) | Ankle Plantarflexion (°) | Knee Flexion (°) | Knee Extension (°) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cha et al., 2017 [15] | 1 | Unhealthy | 22 | −8 | NA | NA |

| Liu et al., 2019 [22] | 12 | Unhealthy | 0 | −2 | 13 | 5 |

| Sarma et al., 2019 [23] | >1 | No Data | 10 | 1 | NA | NA |

| Mavroidis et al., 2011 [26] | 1 | Healthy | 15 | −8 | NA | NA |

| Chae et al., 2020 [28] | 1 | Unhealthy | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Vasiliauskaite et al., 2019 [31] | 6 | Unhealthy | 13 | 0.2 | 12.8 | −2 |

| Telfer et al., 2012 [32] | 1 | Healthy | 18 1; 16 2 | 0 1; −3 2 | 19 1; 15 2 | 10 1; 8 2 |

| Lin, Lin, and Chen, 2017 [33] | 1 | Healthy | NA | NA | 20 | −1 |

| Choi et al., 2017 [34] | 8 | Healthy | 10 | −5 | 17 | 5 |

| Harper et al., 2014 [30] | 13 | Unhealthy | 6.55 3; 5.86 4; 5.68 5 | −6.59 3; −6.03 4; −5.96 5 | 13.38 3; 15.71 4; 17.17 5 | NA |

| Creylman et al., 2013 [29] | 8 | Unhealthy | NA | -3 | 19 | NA |

| Ranz et al., 2016 [35] | 13 | Unhealthy | 5.83 6; 5.19 7; 4.87 8 | −0.68 6; −0.61 7; −0.65 8 | 17.34 6; 17.46 7; 17.85 8 | 5.21 6; 4.69 7; 4.91 8 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Silva, R.; Veloso, A.; Alves, N.; Fernandes, C.; Morouço, P. A Review of Additive Manufacturing Studies for Producing Customized Ankle-Foot Orthoses. Bioengineering 2022, 9, 249. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering9060249

Silva R, Veloso A, Alves N, Fernandes C, Morouço P. A Review of Additive Manufacturing Studies for Producing Customized Ankle-Foot Orthoses. Bioengineering. 2022; 9(6):249. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering9060249

Chicago/Turabian StyleSilva, Rui, António Veloso, Nuno Alves, Cristiana Fernandes, and Pedro Morouço. 2022. "A Review of Additive Manufacturing Studies for Producing Customized Ankle-Foot Orthoses" Bioengineering 9, no. 6: 249. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering9060249

APA StyleSilva, R., Veloso, A., Alves, N., Fernandes, C., & Morouço, P. (2022). A Review of Additive Manufacturing Studies for Producing Customized Ankle-Foot Orthoses. Bioengineering, 9(6), 249. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering9060249