A Qualitative Exploration of the Lived Experiences and Perspectives of Equine-Assisted Services Practitioners in the UK and Ireland

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Approach

2.2. Researcher Reflexivity

2.3. Participant Recruitment

2.4. Data Collection and Preparation

2.5. Maintaining Research Transparency

2.6. Reflexive Thematic Analysis

2.6.1. Phase 1: Familiarisation

2.6.2. Phase 2: Generating Initial Codes

2.6.3. Phase 3: Searching for Themes

2.6.4. Phase 4: Reviewing Themes

2.6.5. Phase 5: Defining and Naming Themes

2.7. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Participant Demographics

3.2. Themes

3.2.1. Theme 1. Developing Strong and Lasting Connections Through Horses

Subtheme: Connection to Horses and the Self

‘the connection with horses has been the grounding…and that connection with horses has given me that place where I can just be…when everything else has, and there have been times, where everything else has just fallen away, and the horses have been a steadying point for me’(Participant 5)

‘There’s something about that relationship and its simplicity, in just being with the horse, just being yourself, them being themselves with you…that feeling…connecting with them and feeling and it’s also nice to feel like they are getting something back from you’(Participant 7)

‘The main thing they [horses] do for me is keeping me grounded, you know, if I’m having a bad day and I’m feeling a bit down they bring me up, and if I’m on top of the world, I’m thinking I’m a great one, they’ll rebalance me, you know, and that’s both the ground [work] and the horse-riding’(Participant 16)

‘[the realisation of]…and that ability to connect with the animal and do things together, and that was kind of, that was a big moment. I think. So I think I remember getting a lot from that in terms of confidence, self-esteem and [through] that sort of connection’(Participant 7)

‘So having that like, really being in your body and really being aware of what you’re doing, with your seat, and your hands and your leg. It’s really…it’s like yoga or dance or any of those types of things. It really brings them down into…into the moment, and that really helps to calm anxiety’(Participant 12)

‘Sometimes we might have a little bit of an idea of what’s going on in our head but, just from doing the work, very few seem to know what’s going on in their bodies and their soul and the horses just join dots for people’(Participant 16)

‘…one of the things that horses teach is, you can be grounded, you can be calm…but even if a horse is startled and runs, at some point, they turn around and look back and stop, and it’s that sort of analogy of ‘It’s ok not to be ok’, but now we have to work out how we can get you back to being ok. So when you’re watching the horses you’re getting that connection of understanding’(Participant 3)

Subtheme: Connection to Others

‘[the horse] is giving that…is this sense of connection, belonging, grounding, mindfulness, less anxiety, less stressful. And it kind of supports the suggestion then that actually they’re not as useless as they thought they were, they’re not as bad as they thought they were, they’re not the label that people have given them. Because what the horse can do is see through all that shit…so let’s get [you] out to the field with the horses and let them, actually work out, what’s going on here’(Participant 3)

‘…and she’ll watch that pony eating, and she’s smiling and laughing, and, like she’s nearly moving her mouth to mimic what the pony’s doing. And it’s a level of connection that you wouldn’t get with a person. She wouldn’t give that attention to another person. She wouldn’t tune into their face, she wouldn’t be aware of their facial expression or movement of their face. So that [opportunity for] connection with something else is amazing’(Participant 7)

‘…in the here and now, without the worry of the past or the fear of the future, and seeing other animals surviving perfectly well in that space’(Participant 11)

3.2.2. Theme 2. It’s All About the Relationships

Subtheme: Building a Strong Therapeutic Alliance

‘…but they probably would struggle [in mainstream therapy] because it’s kind of that traditional setting with the expectations. When we are working in a less traditional setting……they get to see how I am and judge how safe I am by how I interact with the horses. So they can see whether I am trustworthy, kind, supportive person with other beings before they [can] talk to me’(Participant 4)

‘So…that will give them a really good read on how I am going to treat them. If they see me being really pissed off with a horse or not very patient or talking to them in a certain way, than they have sussed out whether I am safe or not. So it’s really important how I embody the relationship in that moment…’(Participant 4)

‘[without which] it’s hard then to facilitate a really high-quality positive session that positively impacts the client, [and] doesn’t negatively impact the horse by any means’(Participant 8)

‘So when they have on the floor confidence as I like to call it…I give them little tasks to do, something simple…go rub the horses, groom, or whatever…to get the connection…and it could be taking the horse for a walk. And that then opens it up and it…It helps us build our therapeutic relationship massively as well because she’s after achieving to us something that was little but to her, it was the world, you know. And from that then I go into the deeper stuff’(Participant 16)

Subtheme: Multiple Opportunities to Practice Relationship Skills Experientially

‘When you add more team players it makes the relationship more complex. So it’s the therapist, it’s the horse handler, it’s the side walker. So it’s the therapists’ relationship with each of these people, it’s their relationship with one another, and it’s the relationship with the client that can all benefit the session or derail it……so the therapeutic relationship also becomes more complex but also can be very beneficial’(Participant 6)

‘Emotionally and mentally the kids just do seem to be very grounded and present around the horses. I do think a lot of that comes from the immediate feedback that horses offer…if they go up and run up to the horse and the horse is a bit like—‘okay’ [not happy with it]—they’re thinking, well, I’ll have to change my behaviour’(Participant 6)

‘It’s about mutuality as well, you know, it’s about sometimes I’m having an off day and the horse is having an off day as well, it’s about allowing that to happen…and then the clients see the relationship that you’ve got, you know through the animals, through the horses…then they give you trust. They know that…they can see you can have a relationship without control’(Participant 13)

‘…the consistency is a big thing for me because the horses aren’t as variable as people’(Participant 7)

‘So he would be saying [at the start] he was really attached to the horses and really wanted to be with them…now when the horses come through he’s not interested, not that he’s not interested in the horses, but because he’s got a relationship with the other therapist and I and he’s missing that human contact. And he trusts us so he doesn’t have to hide behind the horses…so that’s just by osmosis’(Participant 13)

3.2.3. Theme 3. ‘I Couldn’t Do This Without the Horses.’ Horses Enrich the Service and Clients’ Everyday Lives

Subtheme: Horses and the EAS Environment as Unique Motivators

‘But there is something [about horses]. I don’t know if it’s because they’ve got such big hearts, such a big circulatory system going on. That it has, it does have some sort of influence on people. Whether it’s calming, whether it’s from magnetic fields, there is something real in that, but I don’t know what it is. But the effect is…is visible’(Participant 14)

‘The thing that I have found…is that the movement provides such a therapeutic and regulatory effect. So that’s something that’s fantastic. They can come in and can be really heightened…and it’s really the movement of the horse that provides that relaxation’(Participant 6)

‘…lots of kids are…just more engaged because it’s a horse. If you’re more engaged you’re going to get more from it, you’re going to pay better attention, you’re going to be more connected to whatever it is you are working on, you’ll probably remember it more as well, because that’s, you know, a more memorable situation than sitting in a room with somebody’(Participant 7)

‘…when kids are going through or being referred for one-to-one counselling, it’s still very much an environment like school, which they’re not very keen about…which they rail against. Whereas if you bring them out into nature, and that you’re around the horses, and you know, there’s probably dogs and cats and chickens as well, to be honest. So it’s a completely different environment for them…because they know they will be working with these animals they seem to miraculously engage’(Participant 3)

Subtheme: Dynamic Experiential Environment Promotes Growth

‘And the biggest change I find is that confidence growing through experiential learning and exposure to the horses and most people who come here terrified actually want to bring the horses home with them [after]. So it’s about how we embrace fear and how we embrace change’(Participant 2)

‘It’s in front of them, they’re seeing, they’re nearly seeing their thoughts out in front of them, you know. And then it’s live, it’s organic because the horses are free, they can do what they want, no one’s prescribing it…it just makes it so real for them…I couldn’t achieve it in the office, yeah, I couldn’t achieve it in the office and I love my [normal] psychotherapy work’(Participant 16)

Subtheme: Unexpected Co-Benefits to Everyday Life

‘One of the areas we saw was around framing how children were spoken about. And one woman said—my mother always used to say ‘My daughter has a child with disabilities’ and now says ‘My granddaughter goes horse-riding’—and that for me, those are bigger steps than that big dramatic thing where a child learns to speak. Probably that was going to come at some stage…but those [family] connections are more important’(Participant 5)

‘But what I hear all over is that the client sleeps better, not just on the days they had a session…but in general they started sleeping better. For a family where a Mom has to stand up to turn the child 14 times a night, then just being able to do that 9 times a night makes a huge difference…or lessening the amount of oxygen that you give the child…and that is the kinds of things we see all the time’(Participant 6)

3.2.4. Theme 4. EAS Is More than Just Adding a Pony

Subtheme: Awareness Needed of the Strong and Complex Skillset Requirement

‘So you’ll see things on…Facebook like ‘Oh I’m starting to work with kids aged 10. I’ve got no experience of kids. What kind of things will I do with them? You know, I want to say ‘Don’t do it, because you’re not qualified’ You know, it gets people a bad reputation’(Participant 13)

‘I think we don’t necessarily know why or how it works, there’s a lot of theoretical explanations…but I don’t think we fully know yet. And that in some ways undermines it. There are a lot of people who don’t take it seriously and think that it’s just playing with horses…that you don’t have to have any qualifications. You’ve got some horses, you want to help people. Let’s just have a go, which isn’t massively safe or ethical and you wouldn’t see in a lot of [similar] industries’(Participant 4)

‘And there’s also this philosophy that if you’re working with traumatised [clients]…get rescue horses that are traumatised…they will heal each other. So that’s like…so I’ll say ‘If you were going for counselling, if you wanted counselling, you would go to a counsellor that was totally f***ed up would you?’ Well no. So how would you think that…so you’ve got a group of traumatised horses and you’ve got these kids coming from probably an EBD (Emotional and Behaviour Disorder) school…’(Participant 13)

Subtheme: Knowing the Client

‘You have to be very well informed in terms of trauma, nervous system regulation, disability, and just come from a really good place. You have to want to do it in a way that you’re going to preserve the integrity of your client and your horse and you have to try and find that happy medium and trust your instinct and trust your gut with that as you go’(Participant 8)

‘So you have people offering therapeutic riding because they are putting people with disabilities on a horse but they have no training in what they are doing’(Participant 10)

‘I’ve been approached to work with people that have done the equine therapy as an add-on but aren’t horse people, have no horse background and that concerns me…if you don’t have the awareness and the background and the knowledge to read a horses body language that worries me a bit because…I don’t know how you would negotiate that space safely independently….I’ve had people approach me to rent my horse to use them…that didn’t seem safe’(Participant 12)

Subtheme: Knowing the Horses

‘…that day in day out knowing your animals…the same way, you know, farmers know their livestock is the same kind of principle, isn’t it? Just familiarity and it means that you pick up on things before they become issues…nothing is ever getting to the point where the horses are getting unhappy or uncomfortable’(Participant 12)

‘you need to know your horses, you need to observe, and observe, and observe and then better observe, you know, when you think you know them, give yourself a kick and look again. It’s really important that, in terms of relationship, we notice them and they notice us’(Participant 13)

3.2.5. Theme 5. EAS as a Field Is Vulnerable

Subtheme: Sustainability

‘It’s hard work caring for horses and managing a practice. If you were going into therapy or counselling work or coaching work without horses you would be perhaps paying for a room, you know your therapy room, and you may push the hoover around a couple of times a week…when you are working with horses it’s 24/7, managing things that can have their own crisis, can be unwell, you are managing the elements and how your world is affected by the winds, rain storms’(Participant 15)

‘There are easier ways to make money’(Participant 14)

‘I think even the longevity of it…there isn’t a long shelf life in this industry, and I think a lot of it has to do with the physical side. Even the amount of time it takes. It might work for people until they have a family and kids and then all of sudden it doesn’t’(Participant 8)

Subtheme: EAS as a Disjointed Field

‘Yeah I think there’s a kind of disconnect between competencies, like, there isn’t an established competency framework that is known out there in the rest of the world…so there’s something around standardising and competency frameworks [needed]’(Participant 15)

‘If there was a kind of one stop shop for professionals in this field, I think that would be really good. Now there could be, but I haven’t found it, you know, I still don’t know who to join…that’s really something that would be amazing to have, a professional network, professional development, when you join an organisation you know you’re really getting value’(Participant 2)

‘How do I benchmark myself, how do I actually know that I am actually being the best that I can be? There’s nothing. It’s like water. There’s nothing to mark against’(Participant 2)

‘And that comes back to this, sort of idea of consistency, I think. And not that it has to be the same [ training or service] but just, that it should be consistent. And I think there’s a lot of stuff out there that is, like you know, even distance learning courses that…there isn’t kind of consistency along peoples’ training or background…that’s a little problematic, and there only has to be, you know, a bad accident for insurance to be like, we’re just not doing that anymore and then we’re all going to be in a hole aren’t we’(Participant 12)

‘…fundamentally everyone can pretty much do their own thing. But I think we have to look carefully at….what’s the difference between a practitioner who’s done a 5-day online course and somebody who’s done a complete [...] training with practice clients and supervision and everything else. I’m afraid there will be a difference. Because there’ll be a difference in the quality of the knowledge, extent of the knowledge and extent of the training……because 90% of the learning is being with the horses’(Participant 3)

‘[in other professions] you take some exams and then you have finally a face-to-face interview [with a panel] and then you qualify. What that gives everyone outside is, they know the standard of that qualification…and that’s what we don’t have. You know, we have all sorts everywhere’(Participant 3)

‘There would be very few that I would have worked with that would be open to seeing horses in this role, in this dynamic way…Unfortunately in the equine industry, for a lot of people, horses would be robotic, they’re a commodity, you know, which is the bad side of the equestrian industry, probably why I left’(Participant 16)

‘[Organisational CPD/Events] so you’re all the time getting self-care within it which is massive in this field, absolutely massive. So yes, there’s a self-care element of it, a wellbeing element of it. And for me, that’s so important. And the [organisational] network, I suppose we nearly have a community…and that for me is so important and we all back each other, it’s very supportive’(Participant 16)

‘I would like to see us as an industry developing a professional standard that, is like a supervision that you would have in other types of structured organisations, because it’s nice to have someone to run things by and it’s important for quality control. And I think a lot of people are working in isolation, which probably makes them quite vulnerable because we do get disclosures…so it’s quite difficult to navigate. I think I find it quite difficult to navigate’(Participant 12)

4. Discussion

4.1. Developing Strong and Lasting Connections Through Horses

4.2. It’s All About the Relationships

4.3. Horses Enrich the Process

4.4. More than Just ‘Adding a Pony’

4.5. EAS as a Field Is Vulnerable

4.6. Future Recommendations

4.7. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bass, M.M.; Duchowny, C.A.; Llabre, M.M. The effects of therapeutic horseback riding on social functioning in children with autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2009, 39, 1261–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriels, R.L.; Pan, Z.; Dechant, B.; Agnew, J.A.; Brim, N.; Mesibov, G. Randomized controlled trial of therapeutic horseback riding in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2015, 54, 541–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDaniel Peters, B.C.; Wood, W. Autism and equine-assisted interventions: A systematic mapping review. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2017, 47, 3220–3242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aviv, T.-L.M.; Katz, Y.J.; Berant, E. The Contribution of Therapeutic Horseback Riding to the Improvement of Executive Functions and Self-Esteem Among Children with ADHD. J. Atten. Disord. 2021, 25, 1743–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, P.W.; Lazarov, A.; Lowell, A.; Arnon, S.; Turner, J.B.; Bergman, M.; Ryba, M.; Such, S.; Marohasy, C.; Zhu, X.; et al. Equine-Assisted Therapy for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Among Military Veterans. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2021, 82, 21m14005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederick, K.E.; Ivey Hatz, J.; Lanning, B. Not just horsing around: The impact of equine-assisted learning on levels of hope and depression in at-risk adolescents. Community Ment. Health J. 2015, 51, 809–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoagwood, K.E.; Acri, M.; Morrissey, M.; Peth-Pierce, R.; Seibel, L.; Seag, D.E.; Vincent, A.; Guo, F.; Hamovitch, E.K.; Horwitz, S. Adaptive Riding Incorporating Cognitive-Behavioral Elements for Youth with Anxiety: An Exploratory Randomized Controlled Study. Hum.-Anim. Interact. Bull. 2021, 9, 60–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall, E.; Maujean, A. Horse play: A brief psychological intervention for disengaged youths. J. Creat. Ment. Health 2015, 10, 46–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, E.; Davies, B.; Wolfe, R.; Raadsveld, R.; Heine, B.; Thomason, P.; Dobson, F.; Graham, H.K. A randomized controlled trial of the impact of therapeutic horse riding on the quality of life, health, and function of children with cerebral palsy. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2009, 51, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavín-Pérez, A.M.; Collado-Mateo, D.; Caña-Pino, A.; Villafaina, S.; Parraca, J.A.; Apolo-Arenas, M.D. Benefits of Equine-Assisted Therapies in People with Multiple Sclerosis: A Systematic Review. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2022, 2022, 9656503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macauley, B.L.; Gutierrez, K.M. The effectiveness of hippotherapy for children with language-learning disabilities. Commun. Disord. Q. 2004, 25, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakely, J.M. Critical Aspects of Equine Assisted Therapy: A Qualitative Study. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Colorado at Denver, Denver, CO, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Burgon, H.L. ‘Queen of the world’: Experiences of ‘at-risk’ young people participating in equine-assisted learning/therapy. J. Soc. Work. Pract. 2011, 25, 165–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, J. Exploring the Impact of Equine Facilitated Learning on the Social and Emotional Well-Being of Young People Affected by Educational Inequality. Doctoral Dissertation, Dublin City University, Dublin, Ireland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Stoppard, L.; Donaldson, J. Evaluation of equine-assisted learning in education for primary school children: A qualitative study of the perspectives of teachers. Front. Educ. 2024, 9, 1275280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seery, R.; Wells, D. An Exploratory Study into the Backgrounds and Perspectives of Equine-Assisted Service Practitioners. Animals 2024, 14, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelle, U. Combining qualitative and quantitative methods in research practice: Purposes and advantages. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 293–311. [Google Scholar]

- Dźwigoł, H. The Role of Qualitative Methods in Social Research: Analyzing Phenomena Beyond Numbers; Scientific Papers of Silesian University of Technology; Silesian University of Technology Publishing House: Gliwice, Poland, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, W.M. What Is Qualitative Research? An Overview and Guidelines. Australas. Mark. J. 2024, 33, 014413582241264619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gough, B.; Lyons, A. The future of qualitative research in psychology: Accentuating the positive. Integr. Psychol. Behav. Sci. 2016, 50, 234–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queirós, A.; Faria, D.; Almeida, F. Strengths and limitations of qualitative and quantitative research methods. Eur. J. Educ. Stud. 2017, 3, 369–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, K.A.; Orr, E.; Durepos, P.; Nguyen, L.; Li, L.; Whitmore, C.; Gehrke, P.; Graham, L.; Jack, S.M. Reflexive thematic analysis for applied qualitative health research. Qual. Rep. 2021, 26, 2011–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qual. Res. Psychol. 2021, 18, 328–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Supporting best practice in reflexive thematic analysis reporting in Palliative Medicine: A review of published research and introduction to the Reflexive Thematic Analysis Reporting Guidelines (RTARG). Palliat Med. 2024, 38, 608–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, A.J. Applying critical realism in qualitative research: Methodology meets method. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2017, 20, 181–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauzier-Jobin, F.; Brunson, L.; Olson, B. Introduction to the special issue on critical realism. J. Community Psychol. 2025, 53, e22981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Toward good practice in thematic analysis: Avoiding common problems and be (com) ing a knowing researcher. Int. J. Transgender Health 2023, 24, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malterud, K.; Siersma, V.D.; Guassora, A.D. Sample size in qualitative interview studies: Guided by information power. Qual. Health Res. 2016, 26, 1753–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birke, L. Learning to speak horse”: The culture of” Natural Horsemanship. Soc. Anim. 2007, 15, 217–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hockenhull, J.; Birke, L.; Creighton, E. The horse’s tale: Narratives of caring for/about horses. Soc. Anim. 2010, 18, 331–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurício, L.S.; Leme, D.P.; Hötzel, M.J. The easiest becomes the rule: Beliefs, knowledge and attitudes of equine practitioners and enthusiasts regarding horse welfare. Animals 2024, 14, 1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagerty, B.M.; Lynch-Sauer, J.; Patusky, K.L.; Bouwsema, M. An emerging theory of human relatedness. Image J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 1993, 25, 291–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macri, A.M.; Wells, D.L. Connecting to zoos and aquariums during a COVID-19 lockdown. J. Zool. Bot. Gard. 2023, 4, 476–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hultsjö, S.; Jormfeldt, H. The Role of the Horse in an Equine-Assisted Group Intervention-as Conceptualized by Persons with Psychotic Conditions. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2022, 43, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, E.O. Biophilia; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Peppard, L. The Connection Paradigm. J. Am. Psychiatr. Nurses Assoc. 2024, 30, 914–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peppard, L. Board of directors’ column: Building connection competence. J. Am. Psychiatr. Nurses Assoc. 2024, 30, 187–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wickramaratne, P.J.; Yangchen, T.; Lepow, L.; Patra, B.G.; Glicksburg, B.; Talati, A.; Adekkanattu, P.; Ryu, E.; Biernacka, J.M.; Charney, A.; et al. Social connectedness as a determinant of mental health: A scoping review. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0275004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, K.L.; Johnson-Koenke, R.; Fort, M.P. What Is Social Connection in the Context of Human Need: An Interdisciplinary Literature Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacioppo, J.T.; Cacioppo, S. The growing problem of loneliness. Lancet 2018, 39, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno-Agostino, D.; Wu, Y.-T.; Daskalopoulou, C.; Hasan, M.T.; Huisman, M.; Prina, M. Global trends in the prevalence and incidence of depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 281, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, S.-Q.; Cheng, J.-L.; Li, Y.-Y.; Yang, X.-Q.; Zheng, J.-W.; Chang, X.-W.; Shi, Y.; Chen, Y.; Lu, L.; Sun, Y.; et al. Global prevalence of digital addiction in general population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2022, 92, 102128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardinha, L.; Maheu-Giroux, M.; Stöckl, H.; Meyer, S.R.; García-Moreno, C. Global, regional, and national prevalence estimates of physical or sexual, or both, intimate partner violence against women in 2018. Lancet 2022, 399, 803–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanton, B.; Davis, B.; Laraque-Arena, D. Global Burden of Violence. Pediatr. Clin. 2021, 68, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinucci, M.; Pancani, L.; Aureli, N.; Riva, P. Online social connections as surrogates of face-to-face interactions: A longitudinal study under Covid-19 isolation. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2022, 128, 107102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, E.N. Overcoming the Barriers to Self-Knowledge:Mindfulness as a Path to Seeing Yourself as You Really Are. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2013, 8, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt-Lunstad, J. The major health implications of social connection. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2021, 30, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klussman, K.; Langer, J.; Nichols, A.L.; Curtin, N. What’s stopping us from connecting with ourselves? A qualitative examination of barriers to self-connection. Int. J. Appl. Posit. Psychol. 2020, 5, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waite, S.; Husain, F.; Scandone, B.; Forsyth, E.; Piggott, H. ‘It’s not for people like (them)’: Structural and cultural barriers to children and young people engaging with nature outside schooling. J. Adventure Educ. Outdoor Learn. 2023, 23, 54–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Al Mahmud, A.; Liu, W. Social connections and participation among people with mild cognitive impairment: Barriers and recommendations. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1188887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stafford, M.; Von Wagner, C.; Perman, S.; Taylor, J.; Kuh, D.; Sheringham, J. Social connectedness and engagement in preventive health services: An analysis of data from a prospective cohort study. Lancet Public Health 2018, 3, e438–e446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirchio, S.; Passiatore, Y.; Panno, A.; Cipparone, M.; Carrus, G. The effects of contact with nature during outdoor environmental education on students’ wellbeing, connectedness to nature and pro-sociality. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 648458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capizzi, R.; Kempton, H.M. Nature Connection, Mindfulness, and Wellbeing: A Network Analysis. OBM Integr. Complement. Med. 2023, 8, 050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, R.; Kettner, H.; Geerts, D.; Gandy, S.; Kartner, L.; Mertens, L.; Timmermann, C.; Nour, M.M.; Kaelen, M.; Nutt, D. The Watts Connectedness Scale: A new scale for measuring a sense of connectedness to self, others, and world. Psychopharmacology 2022, 239, 3461–3483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, R.M.; Robbins, S.B. The relationship between social connectedness and anxiety, self-esteem, and social identity. J. Couns. Psychol. 1998, 45, 338–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, M. The power of connection: Self-care strategies of social wellbeing. J. Interprof. Educ. Pract. 2023, 31, 100586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooqi, S.R. The Construct of Relationship Quality. J. Relatsh. Res. 2014, 5, e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gille, F. About the Essence of Trust: Tell the Truth and Let Me Choose—I Might Trust You. Int. J. Public Health 2022, 67, 1604592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, P.; Calnan, M.; Scrivener, A.; Szmukler, G. Trust in Mental Health Services: A neglected concept. J. Ment. Health 2009, 18, 449–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frith, C.D.; Frith, U. How we predict what other people are going to do. Brain Res. 2006, 1079, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gweon, H. Inferential social learning: Cognitive foundations of human social learning and teaching. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2021, 25, 896–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horsburgh, J.; Ippolito, K. A skill to be worked at: Using social learning theory to explore the process of learning from role models in clinical settings. BMC Med. Educ. 2018, 18, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pendry, P.; Carr, A.M.; Roeter, S.M.; Vandagriff, J.L. Experimental trial demonstrates effects of animal-assisted stress prevention program on college students’ positive and negative emotion. Hum.-Anim. Interact. Bull. 2018, 6, 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertika, A.; Mitskidou, P.; Stalikas, A. “Positive Relationships” and their impact on wellbeing: A review of current literature. Psychol. J. Hell. Psychol. Soc. 2020, 25, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, B.C.; Wood, W.; Hepburn, S. Theoretical development of equine-assisted activities and therapies for children with autism: A systematic mapping review. Hum.-Anim. Interact. Bull. 2020, 8, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, D.L. The facilitation of social interactions by domestic dogs. Anthrozoös 2004, 17, 340–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallon, G.P. A generous spirit: The work and life of Boris Levinson. Anthrozoös 1994, 7, 224–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baier, A.L.; Kline, A.C.; Feeny, N.C. Therapeutic alliance as a mediator of change: A systematic review and evaluation of research. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2020, 82, 101921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, D.; Wampold, B.E.; Rubel, J.A.; Schwartz, B.; Poster, K.; Schilling, V.N.; Deisenhofer, A.-K.; Hehlmann, M.I.; Gómez Penedo, J.M.; Lutz, W. The influence of extra-therapeutic social support on the association between therapeutic bond and treatment outcome. Psychother. Res. 2021, 31, 726–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feeney, B.C.; Van Vleet, M.; Jakubiak, B.K.; Tomlinson, J.M. Predicting the pursuit and support of challenging life opportunities. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2017, 43, 1171–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauge, H.; Kvalem, I.L.; Berget, B.; Enders-Slegers, M.J.; Braastad, B.O. Equine-assisted activities and the impact on perceived social support, self-esteem and self-efficacy among adolescents—An intervention study. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 2014, 19, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, T.; Perlman, M.R.; McCarrick, S.M.; McClintock, A.S. Modeling therapist responses with structured practice enhances facilitative interpersonal skills. J. Clin. Psychol. 2020, 76, 659–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burch, G.F.; Giambatista, R.; Batchelor, J.H.; Burch, J.J.; Hoover, J.D.; Heller, N.A. A meta-analysis of the relationship between experiential learning and learning outcomes. Decis. Sci. J. Innov. Educ. 2019, 17, 239–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoover, J.D.; Giambatista, R.C.; Belkin, L.Y. Eyes on, hands on: Vicarious observational learning as an enhancement of direct experience. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2012, 11, 591–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batson, C.D.; Ahmad, N.Y. Using empathy to improve intergroup attitudes and relations. Soc. Issues Policy Rev. 2009, 3, 141–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Leal, R.; Costa, A.; Megías-Robles, A.; Fernández-Berrocal, P.; Faria, L. Relationship between emotional intelligence and empathy towards humans and animals. PeerJ 2021, 9, e11274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bove, L.L. Empathy for service: Benefits, unintended consequences, and future research agenda. J. Serv. Mark. 2019, 33, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumble, A.C.; Van Lange, P.A.; Parks, C.D. The benefits of empathy: When empathy may sustain cooperation in social dilemmas. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 40, 856–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, R.; Robertson, R.E.; Smith, R.; Vasconcellos, T.; Lao, M. Which relationship skills count most? A large-scale replication. J. Couple Relatsh. Ther. 2016, 15, 341–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemingway, A. A Study Exploring the Implementation of an Equine Assisted Intervention for Young People with Mental Health and Behavioural Issues. J 2019, 2, 236–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, K.J. Good Friends Have Boundaries: Provider Strategies for Creating Support Boundaries in Friendships. Communication Studies 2024, 76, 350–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsson, C. Equine-assisted social work counteracts self-stigmatisation in self-harming adolescents and facilitates a moment of silence. J. Soc. Work. Pract. 2018, 32, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroll, J. The horse-human bond as catalyst for healing from sexual or domestic abuse: Metaphors in Gillian Mears’ Foal’s Bread. New Writ. 2020, 17, 50–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gearing, R.E.; Townsend, L.; MacKenzie, M.; Charach, A. Reconceptualizing medication adherence: Six phases of dynamic adherence. Harv. Rev. Psychiatry 2011, 19, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rippon, D.; Shepherd, J.; Wakefield, S.; Lee, A.; Pollet, T.V. The role of self-efficacy and self-esteem in mediating positive associations between functional social support and psychological wellbeing in people with a mental health diagnosis. J. Ment. Health 2022, 33, 721–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagle-Holtcamp, K.; Nicodemus, M.C.; Parker, J.; Dunlap, M.H. Does Equine Assisted Learning Create Emotionally Safe Learning Environments for At-Risk Youth? J. Youth Dev. 2019, 14, 232–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corallo, F.; Bonanno, L.; Cardile, D.; Luvarà, F.; Giliberto, S.; Di Cara, M.; Leonardi, S.; Quartarone, A.; Rao, G.; Pidalà, A. Improvement of self-esteem in children with specific learning disorders after donkey-assisted therapy. Children 2023, 10, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souilm, N. Equine-assisted therapy effectiveness in improving emotion regulation, self-efficacy, and perceived self-esteem of patients suffering from substance use disorders. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2023, 23, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messina, J.; Evans, T.; Manson, S.; Shortridge, A.; Deadman, P.; Verburg, P. Complex systems models and the management of error and uncertainty. J. Land Use Sci. 2008, 3, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatteberg, S.J. A tale of many sources: The perceived benefits of significant other, similar other, and significant and similar other social support. Sociol. Perspect. 2021, 64, 37–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, E.; Volsche, S. COVID-19: Companion Animals Help People Cope during Government-Imposed Social Isolation. Soc. Anim. 2021, 32, 56–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConnell, A.R.; Paige Lloyd, E.; Humphrey, B.T. We Are Family: Viewing Pets as Family Members Improves Wellbeing. Anthrozoös 2019, 32, 459–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gee, N.R.; Rodriguez, K.E.; Fine, A.H.; Trammell, J.P. Dogs Supporting Human Health and Well-Being: A Biopsychosocial Approach. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 630465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridén, L.; Sally, H.; Marie, L.; Jormfeldt, H. Relatives’ experiences of an equine-assisted intervention for people with psychotic disorders. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2022, 17, 2087276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssens, M.; Janssens, E.; Eshuis, J.; Lataster, J.; Simons, M.; Reijnders, J.; Jacobs, N. Companion animals as buffer against the impact of stress on affect: An experience sampling study. Animals 2021, 11, 2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bert, F.; Gualano, M.R.; Camussi, E.; Pieve, G.; Voglino, G.; Siliquini, R. Animal assisted intervention: A systematic review of benefits and risks. Eur. J. Integr. Med. 2016, 8, 695–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell-Yeo, M.L.; Disher, T.C.; Benoit, B.L.; Johnston, C.C. Understanding kangaroo care and its benefits to preterm infants. Pediatr. Health Med. Ther. 2015, 6, 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Field, T. Touch for socioemotional and physical well-being: A review. Dev. Rev. 2010, 30, 367–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, I. Keep calm and cuddle on: Social touch as a stress buffer. Adapt. Hum. Behav. Physiol. 2016, 2, 344–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saluja, S.; Croy, I.; Stevenson, R.J. The functions of human touch: An integrative review. J. Nonverbal Behav. 2024, 48, 387–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward-Griffin, E.; Klaiber, P.; Collins, H.K.; Owens, R.L.; Coren, S.; Chen, F.S. Petting away pre-exam stress: The effect of therapy dog sessions on student well-being. Stress Health 2018, 34, 468–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beetz, A.; Uvnäs-Moberg, K.; Julius, H.; Kotrschal, K. Psychosocial and Psychophysiological Effects of Human-Animal Interactions: The Possible Role of Oxytocin. Front. Psychol. 2012, 3, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beetz, A.M. Theories and possible processes of action in animal-assisted interventions. Appl. Dev. Sci. 2017, 21, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrovici, A.; Dobrescu, T. The Role of Emotional Intelligence in Building Interpersonal Communication Skills. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 116, 1405–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salovey, P.; Mayer, J.D. Emotional intelligence. Imagin. Cogn. Personal. 1990, 9, 185–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, D.J.; Evans, T.R. Putting ‘emotional intelligences’ in their place: Introducing the integrated model of affect-related individual differences. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llamas-Díaz, D.; Cabello, R.; Megías-Robles, A.; Fernández-Berrocal, P. Systematic review and meta-analysis: The association between emotional intelligence and subjective well-being in adolescents. J. Adolesc. 2022, 94, 925–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delhom, I.; Satorres, E.; Meléndez, J.C. Emotional intelligence intervention in older adults to improve adaptation and reduce negative mood. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2022, 34, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, C.-K.; Cheung, H.Y.; Hue, M.-T. Emotional intelligence as a basis for self-esteem in young adults. J. Psychol. 2015, 149, 63–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schutte, N.S.; Malouff, J.M.; Thorsteinsson, E.B.; Bhullar, N.; Rooke, S.E. A meta-analytic investigation of the relationship between emotional intelligence and health. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2007, 42, 921–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, D.Y.; Mack, J.M.; McCurdy, K.G. Can an Equine-Assisted Learning Course Improve Emotional Intelligence in Undergraduate Students? People Anim. Int. J. Res. Pract. 2024, 7, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Krüger, L.; Hohberg, M.; Lehmann, W.; Dresing, K. Assessing the risk for major injuries in equestrian sports. BMJ Open Sport Exerc. Med. 2018, 4, e000408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meredith, L.; Ekman, R.; Brolin, K. Epidemiology of equestrian accidents: A literature review. Internet J. Allied Health Sci. Pract. 2019, 17, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luke, K.L.; McAdie, T.; Smith, B.P.; Warren-Smith, A.K. New insights into ridden horse behaviour, horse welfare and horse-related safety. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2022, 246, 105539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riding for the Disabled Association. Home. Riding for the Disabled Association. Available online: https://rda-learning.org.uk/all-courses/ (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Du Plessis, N.; Uys, K.; Buys, T. Hippotherapy concepts: A scoping review to inform transdisciplinary practice guidelines. Scand. J. Occup. Ther. 2023, 30, 1424–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanFleet, R.; Faa-Thompson, T. Animal Assisted Play Therapy TM; Professional Resource Press: Sarasota, FL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, D.W. “First Time” Horse Ownership: Selecting Horses and Budgeting Horse Interests. 2013. Available online: https://openresearch.okstate.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/c03d661c-1f13-4b48-8809-0e255a701c33/content (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Equine Assisted Services in Northern Ireland: An Exploratory Survey of Practitioners; One Equine. Available online: https://oneequine.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/One-Equine-Report-2023-2.pdf (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Galt, R.E. The moral economy is a double-edged sword: Explaining farmers’ earnings and self-exploitation in community-supported agriculture. Econ. Geogr. 2013, 89, 341–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- British Grooms Association. BGA Survey 2024; British Grooms Association: London, UK, 2024; Available online: https://britishgrooms.org.uk/blog/790/latest-bga-research-shocking (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Morris, L. Looking a gift horse in the mouth: Working students under the Fair Labor Standards Act. Wash. Lee Law Rev. 2023, 80, 445. [Google Scholar]

- Sylvia, E.; Currie, E. The Equine Industry Employment Crisis: Exploring Opinions of Employment Practices within the Ontario Equine Industry. Organ. Cult. 2022, 22, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, N.; Thompson, N.; Jooste, J. Why the long face? Experiences and observations of bullying behaviour at equestrian centres in Great Britain. Eur. J. Sport Soc. 2024, 21, 374–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spett, D. Towards Ethical and Competent Equine-Assisted Social Work: A Qualitative Study. Stud. Clin. Soc. Work. Transform. Pract. Educ. Res. 2023, 94, 24–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fine, A.H.; Andersen, S.J. A Commentary on the Contemporary Issues Confronting Animal Assisted and Equine Assisted Interactions. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2021, 100, 103436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartwig, E.K.; Pliske, M.M. Are you and your dog competent? Integrating animal-assisted play therapy competencies. Int. J. Play. Ther. 2023, 32, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, A. What are the Short and Long-Term Impacts of Animal Assisted Interventions on the Therapy Animals? J. Appl. Anim. Ethics Res. 2024, 1, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevathan-Minnis, M.; Schroeder, K.; Eccles, E. Changing with the times: A qualitative content analysis of perceptions toward the study and practice of human–animal interactions. Humanist. Psychol. 2023, 51, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallberg, L. The Clinical Practice of Equine-Assisted Therapy: Including Horses in Human Healthcare; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, J.; Owers, R.; Campbell, M.L.H. Social Licence to Operate: What Can Equestrian Sports Learn from Other Industries? Animals 2022, 12, 1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heleski, C.; Stowe, C.J.; Fiedler, J.; Peterson, M.L.; Brady, C.; Wickens, C.; MacLeod, J.N. Thoroughbred Racehorse Welfare through the Lens of ‘Social License to Operate—With an Emphasis on a US Perspective. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, T.Q.; Brown, A.F. Champing at the bit for improvements: A review of equine welfare in equestrian sports in the United Kingdom. Animals 2022, 12, 1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmquist, G.T.; Alveheim, N.K.; Huot-Marchand, F.; Ashton, L.; Lewis, V. The Role of European Equestrian Institutions in Training Professionals: Outcomes from a Workshop on Horse Welfare in Equestrian Education. Animals 2025, 15, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J. ‘I Can’t Watch Anymore’: The Case for Dropping Equestrian from the Olympic Games; Epona Media A/S: Hillerød, Denmark, 2022. [Google Scholar]

| Practitioner Background | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Geographic region | ||

| Northern Ireland | 2 | 13.3 |

| Republic of Ireland | 6 | 40.0 |

| England | 7 | 46.7 |

| Age (in years) | ||

| 30–39 | 2 | 13.3 |

| 40–49 | 4 | 26.7 |

| 50+ | 9 | 60.0 |

| Highest level of completed education | ||

| Secondary level | 1 | 6.7 |

| Tertiary level | 2 | 13.3 |

| Professional qualification | 4 | 26.7 |

| Postgraduate | 8 | 53.3 |

| EAS category (multiple categories) * | ||

| Equine Assisted Physical Health | 2 | 13.3 |

| Equine-Assisted Mental Health | 7 | 46.7 |

| Equine Assisted Learning | 13 | 86.7 |

| Therapeutic/adaptive riding | 5 | 33.3 |

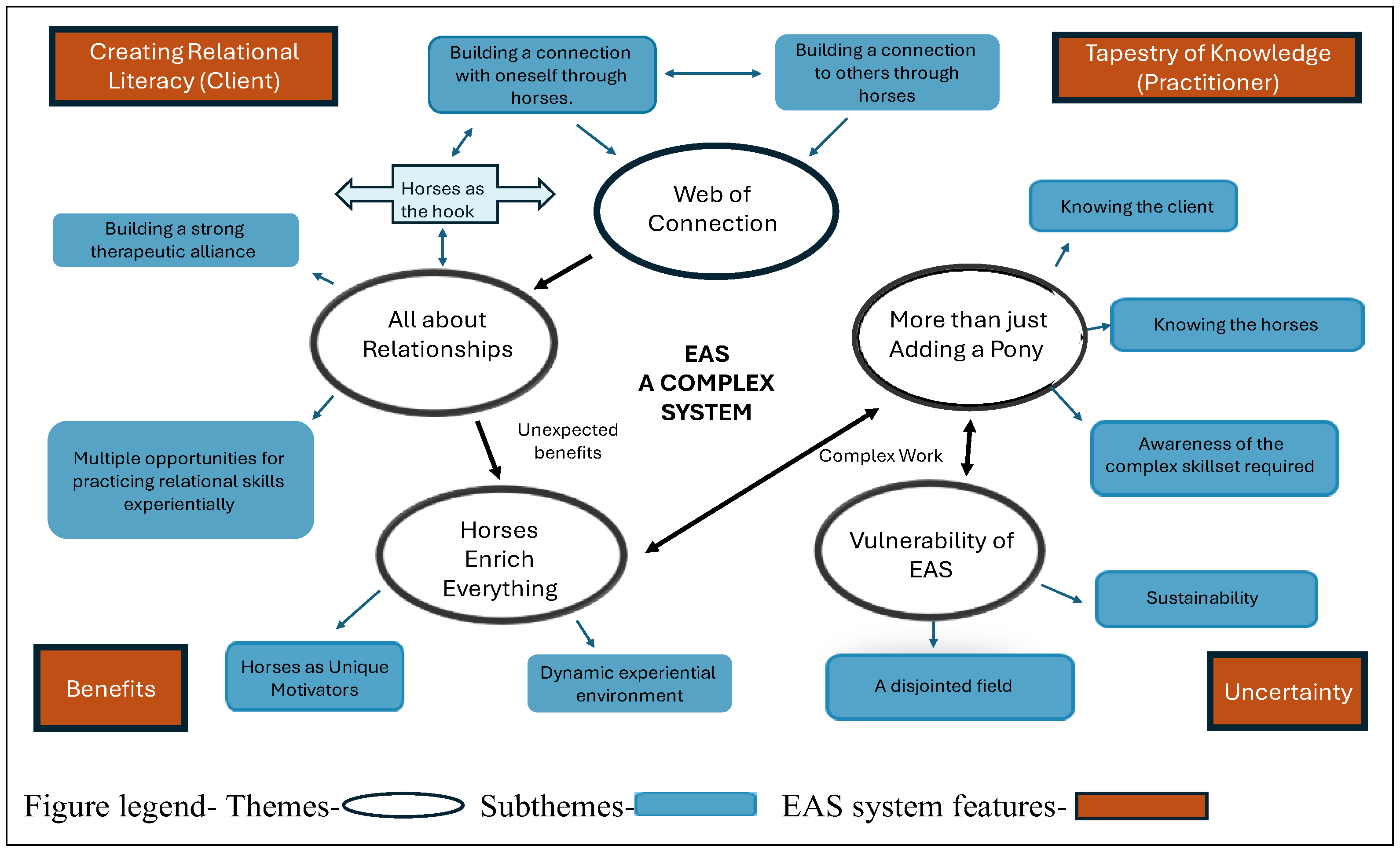

| Theme | Subtheme | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Developing strong and lasting connections through horses | Connection to self through horses Horses facilitate connection to others | Horses act as catalysts for connection on many levels, from the initial spark felt between the client and the horse to improved connection to the self, practitioner, other service personnel, and even the equine and natural environment. The connections act as a web to situate or ground the client. This web of connection helps clients to more quickly feel at home, fostering feelings of safety, acceptance, and being a part of something more than themselves. |

| It’s all about the relationships | Building a strong therapeutic alliance Multiple opportunities to practice relationship skills experientially | A multifaceted relational space. EAS is all about relationships, from the horse-client relationship, practitioner-client relationship, practitioner-horse relationships as well as the multiple multispecies relationships that exist within the team. EAS provides multiple opportunities for practitioners to model good relationships as well as for the client to practice building their multiple parallel relationships that can be transferred to ordinary life. |

| Horses enrich the service | Horses and the EAS environment as unique motivators Dynamic experiential environment promotes growth | Regardless of the service provided, horses contribute something extra into the mix which results in a higher level of outcome that could be achieved via a non-horse service. How this is achieved can be hard to explain and is multifaceted, depending on the service, client, and/or practitioner, but most importantly the presence of the horse in the equation. |

| EAS is more than just adding a pony | Awareness needed of the strong and complex skillset requirement Knowing the client Knowing the horse | EAS is a complex system that requires specialist skills. All EASs consist of numerous ‘moving parts’ and uncertainties that need to be constantly monitored. This dynamic environment can provide added benefits but also increased risk which must be mitigated against. |

| EAS as a field is vulnerable | Sustainability A disjointed field | The general lack of clarity and cohesion along with some confusion within and across the field of EAS leaves the sector open to internal and external threats. This is further aggravated by issues of financial sustainability or vulnerability which is often cited or implied as a challenge in EAS. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Seery, R.; Graham-Wisener, L.; Wells, D.L. A Qualitative Exploration of the Lived Experiences and Perspectives of Equine-Assisted Services Practitioners in the UK and Ireland. Animals 2025, 15, 2240. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15152240

Seery R, Graham-Wisener L, Wells DL. A Qualitative Exploration of the Lived Experiences and Perspectives of Equine-Assisted Services Practitioners in the UK and Ireland. Animals. 2025; 15(15):2240. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15152240

Chicago/Turabian StyleSeery, Rita, Lisa Graham-Wisener, and Deborah L. Wells. 2025. "A Qualitative Exploration of the Lived Experiences and Perspectives of Equine-Assisted Services Practitioners in the UK and Ireland" Animals 15, no. 15: 2240. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15152240

APA StyleSeery, R., Graham-Wisener, L., & Wells, D. L. (2025). A Qualitative Exploration of the Lived Experiences and Perspectives of Equine-Assisted Services Practitioners in the UK and Ireland. Animals, 15(15), 2240. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15152240