Teacher Competencies and School Improvement Specialist Coaching (SISC+) Programme in Malaysia as a Model for Improvement of Quality Education in China

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.1.1. SISC+ Program

1.1.2. Effective Teaching Competencies

1.2. Research Problem

1.3. Objective of the Study

1.4. Research Hypotheses

2. Methodology

2.1. Sampling

2.2. Instrument of Study

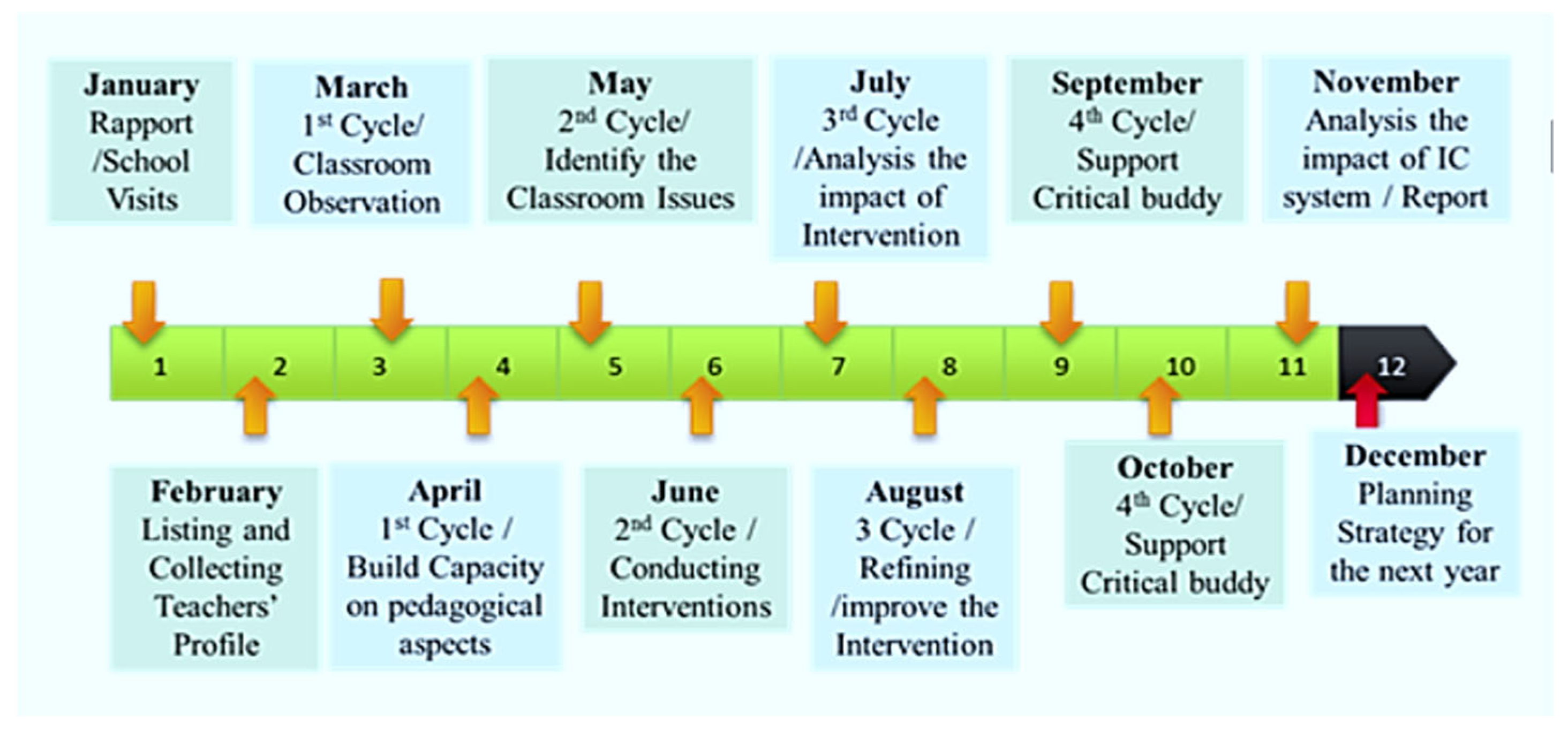

2.3. Study Procedures

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Test (Mean, SD)

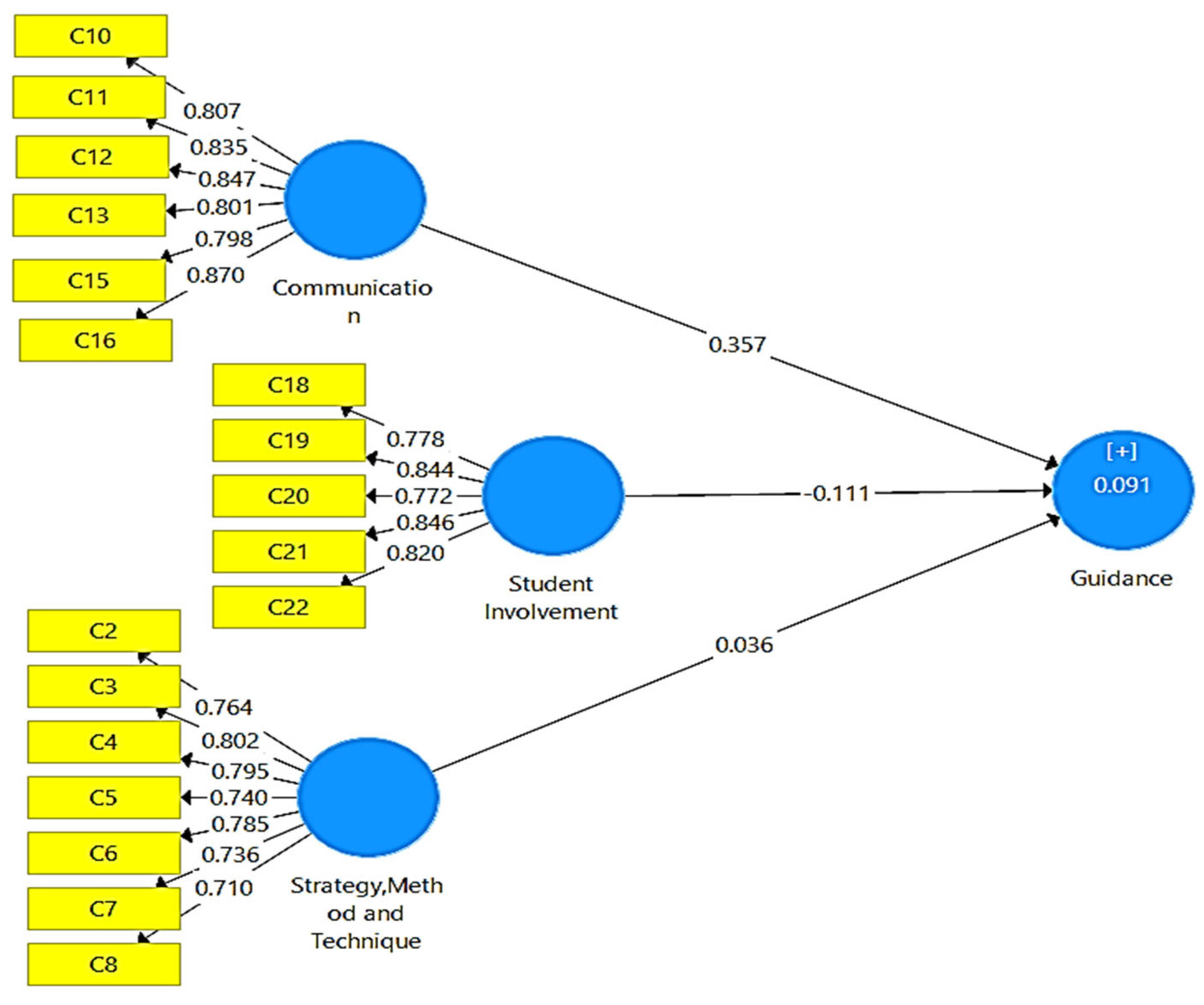

3.1.1. Assessing Reflective Measurement Model

3.1.2. Assessing Formative Measurement Model

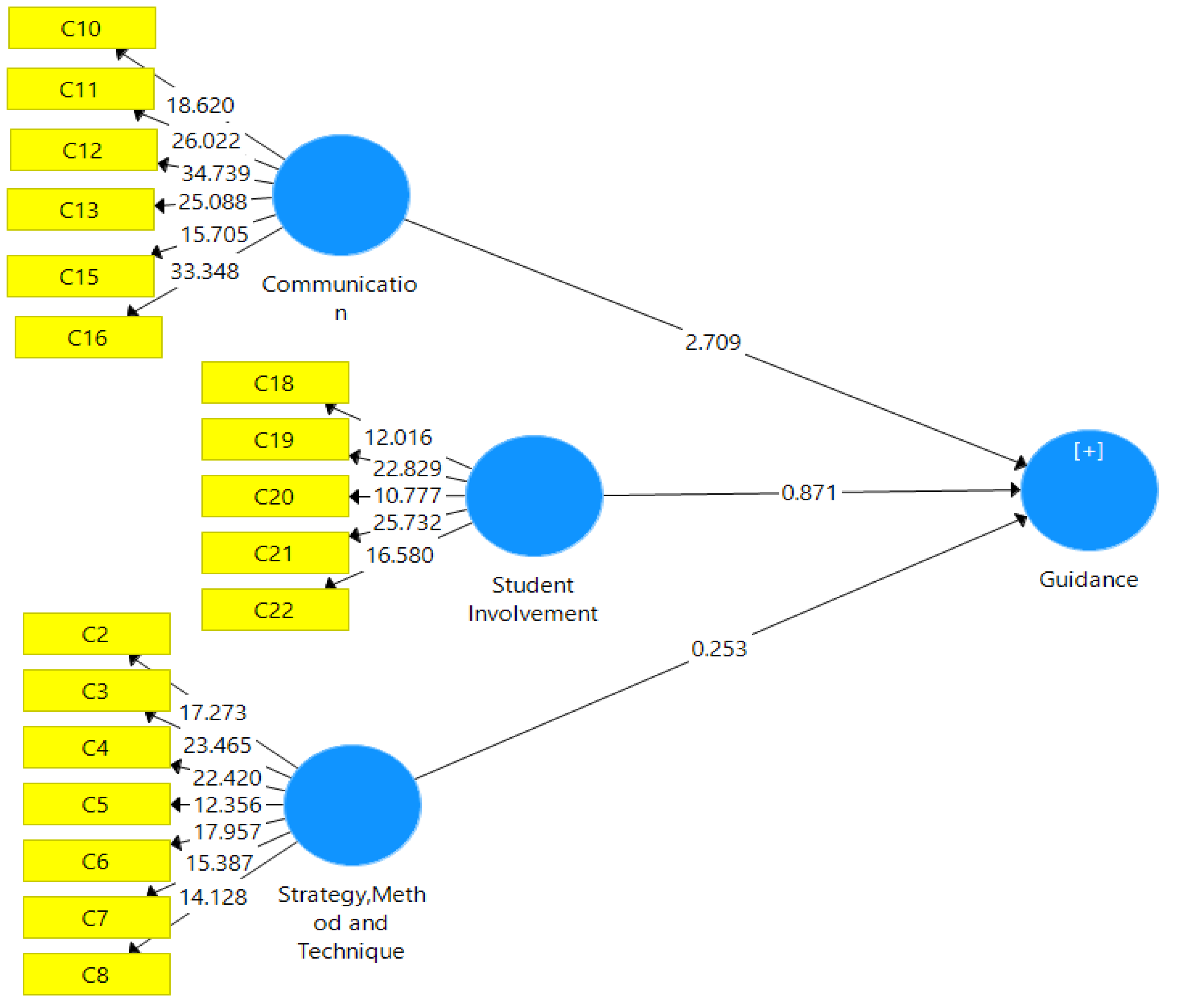

3.1.3. Assessing Structural Model

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Limitations and Possibility of Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Boholano, H.B. Smart Social Networking: 21st Century Teaching and Learning Skills. Res. Pedagog. 2017, 7, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouri, J.; Zhang, L.; Mannila, L.; Norén, E. Development of Computational Thinking, Digital Competence and 21st Century Skills When Learning Programming in K-9. Educ. Inq. 2020, 11, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCoog, I.J. 21st Century Teaching and Learning. Educ. Resour. Cent. 2018. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED502607.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2022).

- Zaidieh, A.J.Y. The Use of Social Networking in Education: Challenges and Opportunities. World Comput. Sci. Inf. Technol. J. 2012, 2, 18–21. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Education. Pelan Pembangunan Pendidikan Malaysia 2013–2025 (Pendidikan Prasekolah Hingga Lepas Menengah) [Malaysian Education Development Plan 2013-20125 (Preschool Education through Secondary)]; Ministry of Education: Putrajaya, Malaysia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, M.Y.; Yusof, M.R.; Yaakob, M.F.M.; Othman, Z. Communication Skills: Top Priority of Teaching Competency. Int. J. Learn. Teach. Educ. Res. 2019, 18, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siraj, S.; Ibrahim, M.S. Standard Kompetensi Guru Malaysia; Fakulti Pendidikan, Universiti Malaya: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cranfield, D.J.; Tick, A.; Venter, I.M.; Blignaut, R.J.; Renaud, K. Higher Education Students’ Perceptions of Online Learning during COVID-19—A Comparative Study. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ober, J.; Kochmańska, A. Remote Learning in Higher Education: Evidence from Poland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, S.W.; Hansen, M.A.; Bernadowski, C. COVID-19 Campus Closures in the United States: American Student Perceptions of Forced Transition to Remote Learning. Soc. Sci. 2021, 10, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamil, N.A. Pengukuran Pembelajaran Kemahiran Berfikir Aras Tinggi Dalam Kalangan Murid Guru Yang Dibimbing (GDB) Oleh Pegawai SISC+. In Simposium Pendidikan diPeribadikan: Perspektif Risalah An-Nur; Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia: Bangi, Malaysia, 2017; pp. 237–248. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, Z.B.M.; Yamat, H.; Wahi, W. School Improvement Specialist Coaches plus (SISC+) Teacher Coaching in Malaysia: Examining the Studies. Int. J. Contemp. Appl. Res. 2019, 6, 125–136. [Google Scholar]

- Malaysian Ministry of Education. Putrajaya: Bahagian Pengurusan Sekolah Harian, 3rd ed.; Bahagian Pengurusan Sekolah Harian: Putrajaya, Malaysia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Balang, N.J.A.; Mahamod, Z.; Buang, N.A. Proficiencies in Curriculum Aspects among School Improvement Specialist Coaches Plus (Sisc+). Univers. J. Educ. Res. 2020, 8, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasser, L.; Zakaria, N.Z.S.; Mukhtar, S.N. Pengaruh Program Intervensi Dalam Bimbingan Dan Pementoran Berfokus Oleh SISC+ Impak Terhadap Kreadibiliti Pengajaran Guru Di Sekolah-Sekolah Daerah Kinta Utara, Perak. In Proceedings of the Prosiding Seminar Darulaman, Peringkat Kebangsaan, Jitra Kedah, Malaysia, 4–5 September 2018; pp. 191–196. [Google Scholar]

- The Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD). PISA 2018 Results (Volume III): What School Life Means for Students’ Lives; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Education (MOE). GTP Road Map of Education; Ministry of Education: Putrajaya, Malaysia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Davrajoo, E.; Letchumanan, E. School Improvement Specialist Coach Plus (SISC+) Programme: Impact on Teachers’ Pedagogical Skills and Students’ Performance in Mathematics Classroom. ASM Sci. J. 2019, 12, 137–149. [Google Scholar]

- Ishak, N.S.; Ibrahim, N. Peranan SISC+ Dalam Pembudayaan Profesional Learning Community (PLC) Di Sekolah [The Role of SISC+ in the Culture of Professional Learning Community (PLC) in Schools]. In Proceedings of the Prosiding Seminar Darulaman, Jitra Kedah, Malaysia, 4–5 September 2018; pp. 452–459. [Google Scholar]

- Khun-Inkeeree, H.; Sohri, N.; Muhammad, M.S.; Yusof, M.R.; Yaakob, M.F.M.; Dromarfauzee, M.S.O.-F.; Wahab, N.M.A.; Sofian, F.N.R.M. Coaching of School Improvement Specialist Coaches plus (SISC+) and Teachers’ Teaching Competency. Intern. J. Adv. Res. 2019, 7, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafee, S.; Abdullah, Z.; Ghavifekr, S. Peranan Amalan Bimbingan Dalam Meningkatkan Pembelajaran Professional Guru. JuPiDi J. Kep. Pendidik. 2019, 6, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Salleh, S.M.; Othman, N. Assessment Level Implementation of School Improvement Specialist Coaches Program: Efficient Teaching Coaches. Int. J. Acad. Res. Progress. Educ. Dev. 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isnon, H.; Badusah, J. Kompetensi Guru Bahasa Melayu Dalam Menerapkan Kemahiran Berfikir Aras Tinggi Dalam Pengajaran Dan Pembelajaran (Malay Language Teacher Competency to Implementation Higher Order Thinking Skill in Teaching and Learning). J. Pendidik. Bhs. Melayu 2017, 7, 56–65. [Google Scholar]

- Dahalan, P.F.H.; Md Saidan, U.S. Penglibatan SISC+ Menerusi ‘Coaching & Mentoring’ Sebagai Pemacu Pembudayaan Pendidikan Abad Ke 21 Di SMK Kampung Bahagia. In Proceedings of the Prosiding Seminar Darulaman 2018, Peringkat Kebangsaan, Jitra Kedah, Malaysia, 4–5 September 2018; pp. 158–165. [Google Scholar]

- Medley, D.M.; Coker, H.; Soar, R.S. Measurement-Based Evaluation of Teacher Performance: An Empirical Approach; Longman Publishing Group: New York, NY, USA, 1984; ISBN 058228502X. [Google Scholar]

- Chua, W.C.; Thien, L.M.; Lim, S.Y.; Tan, C.S.; Guan, T.E. Unveiling the Practices and Challenges of Professional Learning Community in a Malaysian Chinese Secondary School. Sage Open 2020, 10, 2158244020925516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nor, U.N.M.; Mahamod, Z.; Badusah, J. Penerapan Kemahiran Generik Dalam Pengajaran Guru Bahasa Melayu Sekolah Menengah. J. Pendidik. Bhs. Melayu 2016, 1, 71–84. [Google Scholar]

- Dali, P.D.; Daud, K.; Fauzee, M.S.O. The Relationship between Teachers’ Quality in Teaching and Learning with Students’ Satisfaction. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2017, 7, 603–618. [Google Scholar]

- Hilmi, A.; Jamil, A. Persepsi Guru Terhadap Program Pembimbing Pakar Peningkatan Sekolah (SISC+). In Proceedings of the Seminar on Transdisciplinary Education, Sarawak, Malaysia, 11–12 December 2018; pp. 198–205. [Google Scholar]

- Krejcie, R.V.; Morgan, D.W. Determining Sample Size for Research Activities. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1970, 30, 607–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory 3E; Tata McGraw-hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 1994; ISBN 0071070885. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2021; ISBN 1544396414. [Google Scholar]

- Jöreskog, K.G. Simultaneous Factor Analysis in Several Populations. Psychometrika 1971, 36, 409–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantopoulos, A.; Sarstedt, M.; Fuchs, C.; Wilczynski, P.; Kaiser, S. Guidelines for Choosing between Multi-Item and Single-Item Scales for Construct Measurement: A Predictive Validity Perspective. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2012, 40, 434–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A New Criterion for Assessing Discriminant Validity in Variance-Based Structural Equation Modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voorhees, C.M.; Brady, M.K.; Calantone, R.; Ramirez, E. Discriminant Validity Testing in Marketing: An Analysis, Causes for Concern, and Proposed Remedies. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2016, 44, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franke, G.; Sarstedt, M. Heuristics versus Statistics in Discriminant Validity Testing: A Comparison of Four Procedures. Internet Res. Electron. Netw. Appl. Policy 2019, 29, 430–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to Use and How to Report the Results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Gudergan, S.P. Advanced Issues in Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017; ISBN 1483377385. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, C.H.; Perreault, W.D., Jr. Collinearity, Power, and Interpretation of Multiple Regression Analysis. J. Mark. Res. 1991, 28, 268–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, J.-M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Völckner, F. How Collinearity Affects Mixture Regression Results. Mark. Lett. 2015, 26, 643–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Will, S. SmartPLS 2.0 (M3); Beta: Hamburg, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Normawati, S. Permasalahan Mendasar Pendidikan Di Indonesia. J. Al-Idarah Dasar-Dasar Adm. Pendidik. 2014, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Permana, N.S. Peningkatan Mutu Tenaga Pendidik Dengan Kompetensi Dan Sertifikasi Guru. Stud. Didakt. 2017, 11, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Hamdu, G.; Sopandi, W. Debriefing Program for Prospective Elementary School Teachers in Developing Learning Aids. Int. J. Learn. Teach. Educ. Res. 2018, 17, 112–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD). Assessment and Analytical Framework; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Abidin, Y. Revitalisasi Penilaian Pembelajaran Dalam Konteks Pendidikan Multiliterasi Abad Ke-21; Refika Aditama: Bandung, Indonesia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Babar, M.; Tahir, M. The Effects of Big Five Personality Traits on Employee Job Performance among University Lecturers in Peshawar City. Int. J. Manag. Entrep. Res. 2020, 2, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendra, C. The Big Five Personality Traits. Available online: https://www.verywellmind.com/the-big-five-personality-dimensions-2795422 (accessed on 14 October 2022).

- Mohamad, A.S.; Ab Rashid, R.; Yunus, K.; Zaid, S.B. Exploring the School Improvement Specialist Coaches’ Experience in Coaching English Language Teachers. Arab. World Engl. J. 2016, 7, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huong, W.S.; Abdullah, N.A.E. Bimbingan Dan Pementoran Pembimbing Pakar Peningkatan Sekolah (SISC+) Menurut Perspektif Guru Dibimbing (GDB). Int. J. Educ. Psychol. Couns. 2018, 3, 57–72. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, K.C.; Choong, L.K.; Norizan, A.; Lam, K.K.; Siti Mariam, S. Tinjauan Awal Persepsi School Improvement Specialist Coach (SISC+): Perkembangan, Cabaran Dan Ekspektasi. Academia, 1–15 2014. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/13583759/Tinjauan_Awal_Program_Rintis_School_Improvement_Specialist_Coach_Plus_SISC_Isu (accessed on 14 October 2022).

- Jusoh, S. Persepsi, amalan dan keberkesanan bimbingan jurulatih SISC+ dari perspektif guru bahasa Melayu (Perception, Practices and Effectiveness of Guidance SISC+ Coaching from Malay Language Teachers Perspective). J. Pendidik. Bhs. Melayu 2018, 8, 42–52. [Google Scholar]

- Jusoh, S.; Mahamod, Z. Tanggapan, Amalan Dan Keberkesanan Bimbingan Pegawai SISC+ Dari Perspektif Guru Bahasa Melayu. In Prosiding Seminar Pascasiswazah Pendidikan Kesusasteraan Melayu Kali Kelima; Penerbitan Fakulti Pendidikan, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia: Bangi, Malaysia, 2016; pp. 42–52. [Google Scholar]

- Amirullah, A.H.; Iksan, Z.H.; Suarman, H.; Hikmah, N.; Ibrahim, N.H.B.; Iksan, Z.B.H.; Islami, N.; Chairilsyah, D.; Kurnia, R.; Junita, D. Lesson Study: An Approach to Increase the Competency of out-of-Field Mathematics Teacher in Building the Students Conceptual Understanding in Learning Mathematics. J. Educ. Sci. 2018, 2, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jusuf, R.; Sopandi, W.; Wulan, A.R.; Sa’ud, U.S. Strengthening Teacher Competency through ICARE Approach to Improve Literacy Assessment of Science Creative Thinking. Int. J. Learn. Teach. Educ. Res. 2019, 18, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, R.R.; Jamian, A.R.; Sabil, A.M. Pengetahuan Dan Kefahaman Skop Pengajaran Dan Pembelajaran Bahasa Melayu Dalam Kalangan Jurulatih Pakar Pembangunan Sekolah (SISC+). Int. J. Educ. Train. 2016, 2, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Jimbai, N.; Zamri, M. Penerimaan Guru-Guru Bahasa Melayu Terhadap Bimbingan Dan Pementoran SISC+. In Proceedings of the Dalam Seminar Penyelidikan Pendidikan, Kuching, Malaysia, 20–22 March 2017; pp. 280–291. [Google Scholar]

- Vikaraman, S.S.; Mansor, A.N.; Hamzah, M.I.M. Mentoring and Coaching Practices for Beginner Teachers—A Need for Mentor Coaching Skills Training and Principal’s Support. Creat. Educ. 2017, 8, 156–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

| Area | Competencies Characteristic |

|---|---|

| Area I: Instructional strategies, techniques, and methods | 1. Uses a wide variety of instructional techniques. 2. Uses convergent and divergent analytical approaches. 3. Develops and reveals the capacity to solve problems. 4. Sets instruction transitions and sequences that are varied, logical, and relevant. 5. Modifies educational programs to meet the defined needs of the learner. 6. Demonstrates the capacity to interact with people, small groups and large groups. 7. Structures the use of time to make learning easier for students. 8. Requires a wide variety of tools and materials. 9. Provides learning opportunities that enable students to master concepts and generalizations outside of school. |

| Area II: Communication with learner | 10. Provides interactive opportunities for students in a school. 11. Uses a range of practical verbal and non-verbal communication skills with students. 12. Provides simple instructions and explanations. 13. Encourages students to ask questions. 14. Uses questions that lead students to evaluate, synthesize, and think critically. 15. Accepts a range of student experiences and/or allows students to extend or elaborate responses or ideas. 16. Demonstrates the right listening skills. 17. Provides feedback on learners’ academic performance. |

| Area III; Student involvement | 18. Maintains a work-on-task atmosphere in which students are actively involved. 19. Enhances an efficient classroom-management program for maintaining student conduct (discipline). 20. Uses constructive forms of communication with students. 21. Helps students find and correct mistakes and inaccuracies. 22. Develops student reviews, evaluation skills, and student self-assessment. |

| Mean Value | Level |

|---|---|

| 1.00 to 2.00 | Very Low |

| 2.01 to 3.00 | Low |

| 3.01 to 4.00 | Moderate/High Moderate |

| 4.01 to 5.00 | High |

| N | Mean | Standard Deviation (SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Teaching Competency Level | |||

| Communication | 186 | 4.12 | 0.49 |

| Student involvement | 186 | 4.07 | 0.48 |

| Teaching strategy, technique and method | 186 | 3.97 | 0.47 |

| SISC+ Coaching Level | |||

| Guidance | 186 | 3.77 | 0.82 |

| Constructs | Items | Loading | Composite Reliability | Cronbach Alpha | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Communication | C16 | 0.870 | 0.928 | 0.908 | 0.684 |

| C12 | 0.847 | ||||

| C11 | 0.835 | ||||

| C10 | 0.807 | ||||

| C13 | 0.801 | ||||

| C15 | 0.798 | ||||

| Guidance | B1 | 0.898 | 0.987 | 0.986 | 0.824 |

| B10 | 0.917 | ||||

| B11 | 0.933 | ||||

| B12 | 0.933 | ||||

| B13 | 0.898 | ||||

| B14 | 0.901 | ||||

| B15 | 0.918 | ||||

| B16 | 0.923 | ||||

| B2 | 0.913 | ||||

| B3 | 0.903 | ||||

| B4 | 0.931 | ||||

| B5 | 0.902 | ||||

| B6 | 0.826 | ||||

| B7 | 0.885 | ||||

| B8 | 0.914 | ||||

| B9 | 0.920 | ||||

| Teaching Strategy, Method, and Technique | C2 | 0.764 | 0.906 | 0.88 | 0.581 |

| C3 | 0.802 | ||||

| C4 | 0.795 | ||||

| C5 | 0.740 | ||||

| C6 | 0.785 | ||||

| C7 | 0.736 | ||||

| C8 | 0.710 | ||||

| Student Involvement | C18 | 0.778 | 0.907 | 0.873 | 0.661 |

| C19 | 0.844 | ||||

| C20 | 0.772 | ||||

| C21 | 0.846 | ||||

| C22 | 0.820 |

| Communication | Guidance | Teaching Strategy, Method, and Technique | Student Involvement | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Communication | 0.827 | |||

| Guidance | 0.295 | 0.908 | ||

| Teaching Strategy, Method, and Technique | 0.734 | 0.231 | 0.762 | |

| Student Involvement | 0.718 | 0.209 | 0.737 | 0.813 |

| Communication | Guidance | Teaching Strategy, Method, and Technique | Student Involvement | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Communication | ||||

| Guidance | 0.296 | |||

| Teaching Strategy, Method, and Technique | 0.881 | 0.244 | ||

| Student Involvement | 0.827 | 0.211 | 0.885 |

| Items | VIF | Items | VIF | Items | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C10 | 2.734 | C18 | 2.000 | C3 | 2.083 |

| C11 | 2.671 | C19 | 2.114 | C4 | 2.028 |

| C12 | 2.748 | C20 | 1.892 | C5 | 1.784 |

| C13 | 2.537 | C21 | 2.306 | C6 | 2.023 |

| C15 | 2.484 | C22 | 1.998 | C7 | 1.744 |

| C16 | 3.158 | C2 | 1.909 | C8 | 1.637 |

| Relationship | β | p-Value | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Communication → Guidance | 0.348 | 0.007 | Significant |

| Teaching Strategy, Method, and Technique → Guidance | 0.046 | 0.801 | Not Significant |

| Student Involvement → Guidance | −0.089 | 0.384 | Not Significant |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yan, Z.; Na, M.; Alam, S.S.; Masukujjaman, M.; Lu, Y.X. Teacher Competencies and School Improvement Specialist Coaching (SISC+) Programme in Malaysia as a Model for Improvement of Quality Education in China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16273. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142316273

Yan Z, Na M, Alam SS, Masukujjaman M, Lu YX. Teacher Competencies and School Improvement Specialist Coaching (SISC+) Programme in Malaysia as a Model for Improvement of Quality Education in China. Sustainability. 2022; 14(23):16273. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142316273

Chicago/Turabian StyleYan, Zhou, Meng Na, Syed Shah Alam, Mohammad Masukujjaman, and Ye Xiao Lu. 2022. "Teacher Competencies and School Improvement Specialist Coaching (SISC+) Programme in Malaysia as a Model for Improvement of Quality Education in China" Sustainability 14, no. 23: 16273. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142316273

APA StyleYan, Z., Na, M., Alam, S. S., Masukujjaman, M., & Lu, Y. X. (2022). Teacher Competencies and School Improvement Specialist Coaching (SISC+) Programme in Malaysia as a Model for Improvement of Quality Education in China. Sustainability, 14(23), 16273. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142316273