Price Sensitivity of Fish Fed with Insect Meal: An Analysis on Italian Consumers

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Edible Insects’ Consumption

| Positive | Negative |

|---|---|

| Familiarity and Previous Personal Experiences | Disgust |

| Caparros Megido et al. [77] | Caparros-Megido et al. [51] |

| Caparros-Megido et al. [51] | Costa-Neto and Dunkel [76] |

| Hartmann and Siegrist [78] | Gmuer et al. [79] |

| Hartmann et al. [59] | Hartmann and Siegrist [78] |

| Lensvelt and Steenbekkers [80] | Hartmann et al. [59] |

| Menozzi et al. [81] | Meixner and Mörl von Pfalzen [82] |

| Piha et al. [83] | Stockley et al. [84] |

| Sogari et al. [85] | Tan et al. [86] |

| Tan et al. [86] | Van Huis et al. [87] |

| Tan et al. [88] | Verbeke [53] |

| Van Thielen et al. [89] | |

| Verbeke [53] | Healthy risk |

| Vernau et al. [90] | |

| Vernau et al. [91] | Baker et al. [92] |

| Costa-Neto and Dunkel [76] | |

| Environmentally-friendly orientation | Hartmann and Siegrist [78] |

| Hartmann et al. [59] | |

| Gamborg et al. [93] | Meixner and Mörl von Pfalzen [82] |

| Hartmann and Siegrist [55] | Ruby et al. [60] |

| House [54] | |

| Kostecka et al. [94] | Neophobia |

| Lensvelt and Steenbekkers [80] | |

| Menozzi et al. [81] | Borrello et al. [68] |

| Schiemer et al. [72] | Dossey et al. [95] |

| Tan et al. [86] | Hartmann and Siegrist [65] |

| Verbeke [53] | Hartmann and Siegrist [78] |

| Hartmann et al. [59] | |

| Healthiness | Imathiu [52] |

| La Barbera et al. [96] | |

| Cavallo and Materia [97] | Monteleone et al. [98] |

| Gere et al. [99] | Piha et al. [83] |

| Hartmann and Siegrist [55] | Roma et al. [13] |

| Ruby et al. [60] | Schlup and Brunner [100] |

| Schiemer et al. [72] | Verbeke [53] |

| Schlup and Brunner [100] | Wilkinson et al. [101] |

2.2. Price Impact on Consumers

3. Methodology and Materials

3.1. The Van Westendorp Model

- There exist reasonable prices that consumers are able to envision;

- There exists an upper and lower bound to the price that consumers are willing to pay for a product or service;

- Price is an intrinsic measure of value or utility of product or services.

- -

- At what price would you begin to think the product is too expensive to consider (too expensive)?

- -

- At what price would you begin to think the product is so inexpensive that you would question the quality and not consider it (too cheap)?

- -

- At what price would you begin to think the product is getting expensive, but you still might consider it (expensive)?

- -

- At what price would you think the product is a bargain (a great buy for the money–cheap)?

- -

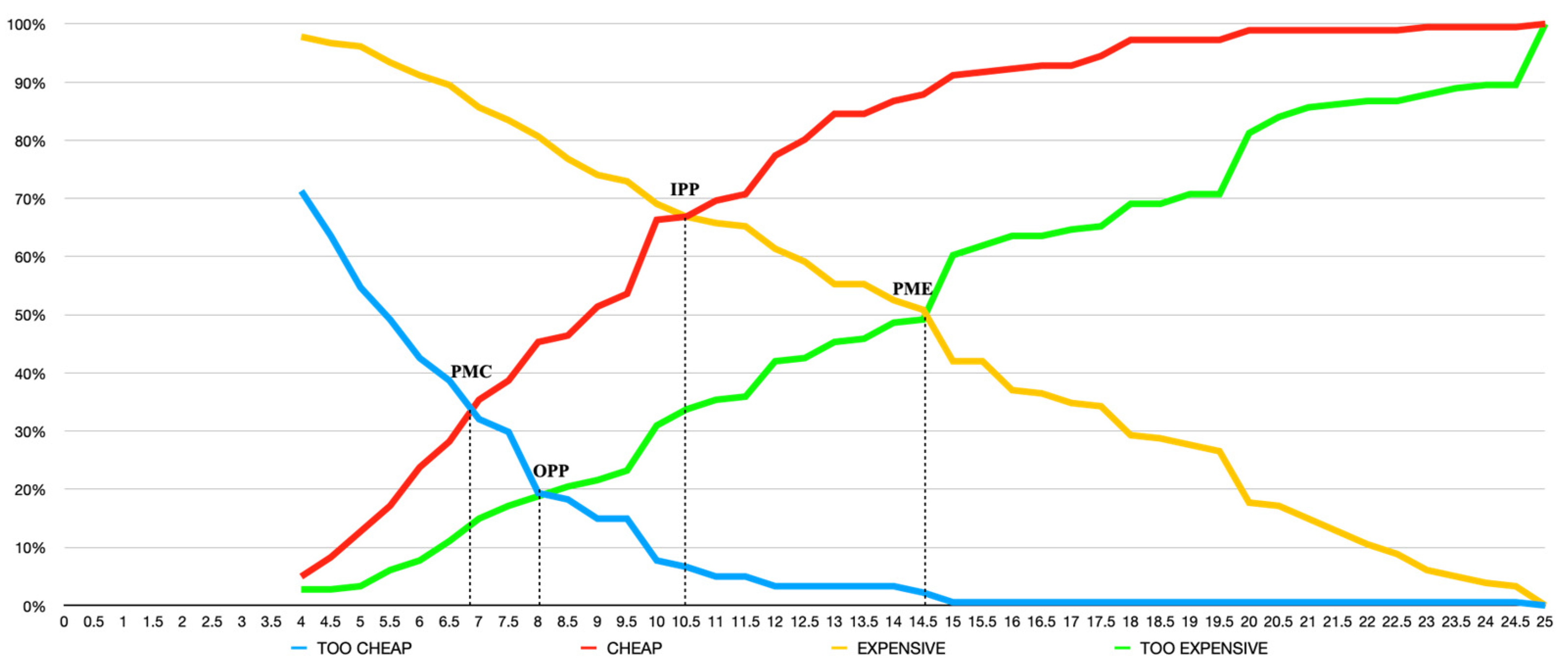

- Point of marginal cheapness (PMC), namely the lowest threshold of the acceptable price range. It is the point where more sales would be lost due to the rapidly increasing proportion of consumers that view the product as too cheap and of questionable quality. In the graph, the point resulting from the intersection of the too-cheap and cheap curves (see Figure 1).

- -

- Point of marginal expensiveness (PME) is the upper threshold of the range of acceptable prices and the point where respondents believe the product is too expensive compared to the value derived from it. In short, it is the inflexion point where the increasing price elasticity of demand is enough to cause demand to fall rapidly and thus can be used as a measure of the willingness to pay limit. Graphically, it is the point of intersection between “expensive” and “too-expensive” curves.

- -

- Optimal price point (OPP) is the point of intersection between too-expensive and too-cheap curves, where an equal number of respondents describe the price as over the upper or lower limit. It is optimal because there is an equal trade-off in extreme price sensitivities at both ends of the price spectrum. In short, it can be considered the “sweet spot” as it maximizes the number of people who find the price acceptable and minimizes the resistance to price changes.

- -

- Indifference price point (IPP), or normal price point, where most respondents are indifferent to the price, and the same number of respondents rate the price as “getting expensive” or “a bargain.” It is the (median) “normal” price in the market, represented graphically by the point of intersection of “expensive” and “cheap” lines.

3.2. Sampling and Data Collection

The increase in the world population, the increased awareness of the significant impact of eating habits on personal health, and the mental and physical health benefits of fish consumption have led to a notable increase in demand for seafood which will reach 28 million tons in 2030. This increase in demand can only be met through fish farming, i.e., aquaculture.

However, the main problem lies in feeding farmed fish, which are still mostly fed with fishmeal today. This entails significant negative impacts not only on the environment but also on the economic and social levels. The unsustainability of this practice has required an urgent rethinking of the protein sources used in fish farming (and beyond).

An alternative has been provided by the European Union, which has recently allowed the breeding of fish with feed derived from some insects.

Recent scientific research has shown that some insects possess numerous properties: the presence of a quantity of proteins, minerals and vitamins very similar to that of fish meal, as well as high in energy, fat and fiber; naturally present in the natural diet of freshwater and marine fish; possibility of local production by small farmers; low environmental impact.

“I have heard of the eating of insects, and I know what it means”;

“I have heard of the eating of insects but actually don’t know what it means”;

“No, I have never heard of the eating of insects”.

4. Results

4.1. Sample Profile

4.2. Acceptable Price Range and Price Thresholds

4.3. Relatively Cheap Price Range and Price Thresholds

4.4. Price–Response Function

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IPP | Indifference price point |

| OPP | Optimal price point |

| PMC | Point of marginal cheapness |

| PME | Point of marginal expensiveness |

| PMS | Price Sensitivity Meter |

| PRF | Price Response Function |

| RAP | Range of acceptable price |

| RRCP | Range of relatively cheap price |

| RREP | Range of relatively expensive price |

| RSP | Range of stress price |

| SF | Stress Factor |

| SK | Subjective Knowledge |

| SPR | Stress Price Range |

| VW | Van Westendorp |

| WTP | Willingness To Pay |

References

- Naylor, R.L.; Goldburg, R.J.; Primavera, J.H.; Kautsky, N.; Beveridge, M.C.M.; Clay, J.; Folke, C.; Lubchenco, J.; Mooney, H.; Troell, M. Effect of aquaculture on world fish supplies. Nature 2000, 405, 1017–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- FAO. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2020; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020; ISBN 978-92-5-132692-3. [Google Scholar]

- Hei, A. Mental Health Benefits of Fish Consumption. Clin. Schizophr. Relat. Psychoses 2020, 15, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Magalhães, R.; Sánchez-López, A.; Leal, R.S.; Martínez-Llorens, S.; Oliva-Teles, A.; Peres, H. Black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens) pre-pupae meal as a fish meal replacement in diets for European seabass (Dicentrarchus labrax). Aquaculture 2017, 476, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arru, B.; Furesi, R.; Gasco, L.; Madau, F.; Pulina, P. The Introduction of Insect Meal into Fish Diet: The First Economic Analysis on European Sea Bass Farming. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Llagostera, P.F.; Kallas, Z.; Reig, L.; de Gea, D.A. The use of insect meal as a sustainable feeding alternative in aquaculture: Current situation, Spanish consumers’ perceptions and willingness to pay. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 229, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musyoka, S.N.; Liti, D.M.; Ogello, E.; Waidbacher, H. Utilization of the earthworm, Eisenia fetida (Savigny, 1826) as an alternative protein source in fish feeds processing: A review. Aquac. Res. 2019, 50, 2301–2315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Oliva-Teles, A.; Enes, P.; Peres, H. Replacing Fishmeal and Fish Oil in Industrial Aquafeeds for Carnivorous Fish. In Feed and Feeding Practices in Aquaculture; Woodhead Publishing Series in Food Science, Technology and Nutrition; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2015; pp. 203–233. ISBN 978-0-08-100506-4. [Google Scholar]

- Food And Agriculture Organization (FAO). The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture: 2018—Meeting the Sustainable Development Goals; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2018; ISBN 978-92-5-130562-1. [Google Scholar]

- Gasco, L.; Gai, F.; Maricchiolo, G.; Genovese, L.; Ragonese, S.; Bottari, T.; Caruso, G. Fishmeal Alternative Protein Sources for Aquaculture Feeds. In Feeds for the Aquaculture Sector; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 1–28. ISBN 978-3-319-77941-6. [Google Scholar]

- Salin, K.R.; Arun, V.; Nair, C.M.; Tidwell, J.H. Sustainable Aquafeed. In Sustainable Aquaculture; Applied Environmental Science and Engineering for a Sustainable Future; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 123–151. ISBN 978-3-319-73256-5. [Google Scholar]

- Mulazzani, L.; Madau, F.A.; Pulina, P.; Malorgio, G. Acceptance of insect meal in aquaculture feeding: A stakeholder analysis for the Italian supply chains of trout and seabass. J. World Aquac. Soc. 2021, 52, 378–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roma, R.; Palmisano, G.O.; De Boni, A. Insects as Novel Food: A Consumer Attitude Analysis through the Dominance-Based Rough Set Approach. Foods 2020, 9, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Borrello, M.; Lombardi, A.; Pascucci, S.; Cembalo, L. The Seven Challenges for Transitioning into a Bio-based Circular Economy in the Agri-food Sector. Recent Patents Food, Nutr. Agric. 2016, 8, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Zanten, H.H.; Mollenhorst, H.; Oonincx, D.; Bikker, P.; Meerburg, B.; De Boer, I. From environmental nuisance to environmental opportunity: Housefly larvae convert waste to livestock feed. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 102, 362–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, M.; Gasco, L.; Piccolo, G.; Fountoulaki, E. Review on the use of insects in the diet of farmed fish: Past and future. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2015, 203, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oonincx, D.G.A.B.; de Boer, I.J.M. Environmental Impact of the Production of Mealworms as a Protein Source for Humans—A Life Cycle Assessment. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e51145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Moruzzo, R.; Mancini, S.; Guidi, A. Edible Insects and Sustainable Development Goals. Insects 2021, 12, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derler, H.; Lienhard, A.; Berner, S.; Grasser, M.; Posch, A.; Rehorska, R. Use Them for What They Are Good at: Mealworms in Circular Food Systems. Insects 2021, 12, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madau, F.A.; Arru, B.; Furesi, R.; Pulina, P. Insect Farming for Feed and Food Production from a Circular Business Model Perspective. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojha, S.; Bußler, S.; Schlüter, O.K. Food waste valorisation and circular economy concepts in insect production and processing. Waste Manag. 2020, 118, 600–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azzurra, A.; Massimiliano, A.; Angela, M. Measuring sustainable food consumption: A case study on organic food. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2019, 17, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, S. Determinants of Consumers’ Purchasing Behavior for Certified Aquaculture Products in South Korea. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ankamah-Yeboah, I.; Jacobsen, J.B.; Olsen, S. Innovating out of the fishmeal trap: The Role of Insect-Based Fish Feed in Consumers’ Preferences for Fish Attributes. Br. Food J. 2018, 120, 2395–2410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De-Magistris, T.; Gracia, A. Consumers’ willingness-to-pay for sustainable food products: The case of organically and locally grown almonds in Spain. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 118, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchio, R.; Annunziata, A. Willingness-to-pay for sustainability-labelled chocolate: An experimental auction approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 86, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Farm to Fork Strategy for a Fair, Healthy and Environmentally-Friendly Food System. 2020. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/food/system/files/2020-05/f2f_action-plan_2020_strategy-info_en.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2022).

- Nazzaro, C.; Lerro, M.; Stanco, M.; Marotta, G. Do consumers like food product innovation? An analysis of willingness to pay for innovative food attributes. Br. Food J. 2019, 121, 1413–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceylana, H.H.; Koseb, B.; Aydin, M. Value based Pricing: A Research on Service Sector Using Van Westendorp Price Sensitivity Scale. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 148, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- de Medeiros, J.F.; Ribeiro, J.L.D.; Cortimiglia, M.N. Influence of perceived value on purchasing decisions of green products in Brazil. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 110, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Liu, L.; Wang, M.; Jiang, X. Propensity of green consumption behaviors in representative cities in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 133, 1328–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, A.K. Consumers’ purchasing decisions regarding environmentally friendly products: An empirical analysis of German consumers. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 31, 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenhuis, I.H.; Waterlander, W.E.; de Mul, A. Consumer food choices: The role of price and pricing strategies. Public Health Nutr. 2011, 14, 2220–2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ingenbleek, P.T.M.; Frambach, R.T.; Verhallen, T.M.M. Best Practices for New Product Pricing: Impact on Market Performance and Price Level under Different Conditions. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2013, 30, 560–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, M.; Eggert, A.; Ulaga, W.; Backhaus, K. Do customized service packages impede value capture in industrial markets? J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2016, 44, 151–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, M.; Hendus, J. How Consumers’ Willingness to Pay Is Measured in Practice: An Empirical Analysis of Common Approaches’ Relevance. SSRN 2012, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winer, R.S. Pricing; Marketing Science Institute: Cambridge, UK, 2005; ISBN 978-0-9657114-6-3. [Google Scholar]

- Van Westendorp, P.H. NSS Price Sensitivity Meter (PSM)–A New Approach to Study Consumer Perception of Prices. In Proceedings of the 29th ESOMAR Congress, Venice, Italy, 5–9 September 1976; pp. 139–167. [Google Scholar]

- Chhabra, S. Determining the Optimal Price Point: Using Van Westendorp’s Price Sensitivity Meter. In Managing in Recovering Markets. Springer Proceedings in Business and Economics; Springer: New Delhi, India, 2015; pp. 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipovetsky, S. Van Westendorp Price Sensitivity in Statistical Modeling. Int. J. Oper. Quant. Manag. 2006, 12, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Lyon, D.W. The Price Is Right (or Is It?). Mark. Res. 2002, 14, 8–13. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T.; Venkatesh, R.; Chatterjee, R. Reservation Price as a Range: An Incentive-Compatible Measurement Approach. J. Mark. Res. 2007, 44, 200–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Roll, O.; Achterberg, L.-H.; Herbert, K.-G. Innovative Approaches to Analyzing the Price Sensitivity Meter: Results of an International Comparative Study. In Combi 2010 Conference Proceedings; Edita Prima Oy: Helsinki, Finland, 2010; pp. 181–193. ISBN 978-951-799-213-8. [Google Scholar]

- FEAP European Aquaculture Production Report 2014–2019. 2020. Available online: http://feap.info/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/20201218_feap-production-report-2020.pdf (accessed on 28 April 2022).

- Pieniak, Z.; Verbeke, W.; Scholderer, J. Health-related beliefs and consumer knowledge as determinants of fish consumption. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. Off. J. Br. Diet. Assoc. 2010, 23, 480–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demartini, E.; Vecchiato, D.; Marescotti, M.E.; Gibbert, M.; Viganò, R.; Giacomelli, S.; Gaviglio, A. The more you know: The equivocal effects of prior knowledge on preferences for hunted vs. farmed wild boar meat. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2021, 24, 100325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Liu, G.-L. The effects of consumer’s subjective and objective knowledge on perceptions and attitude towards genetically modified foods: Objective knowledge as a determinant. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 50, 1198–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altintzoglou, T.; Heide, M. Fish Quality and Consumers: How Do Consumers’ Knowledge about and Involvement in Fish Quality Define Factors That Influence Fish Buying Behavior? J. Aquat. Food Prod. Technol. 2016, 25, 885–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zucchella, A.; Previtali, P. Circular business models for sustainable development: A “waste is food” restorative ecosystem. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2019, 28, 274–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielińska, E.; Zieliński, D.; Karaś, M.; Jakubczyk, A. Exploration of consumer acceptance of insects as food in Poland. J. Insects Food Feed 2020, 6, 383–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megido, R.C.; Gierts, C.; Blecker, C.; Brostaux, Y.; Haubruge, É.; Alabi, T.; Francis, F. Consumer acceptance of insect-based alternative meat products in Western countries. Food Qual. Prefer. 2016, 52, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imathiu, S. Benefits and food safety concerns associated with consumption of edible insects. NFS J. 2019, 18, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbeke, W. Profiling consumers who are ready to adopt insects as a meat substitute in a Western society. Food Qual. Prefer. 2015, 39, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- House, J. Consumer acceptance of insect-based foods in the Netherlands: Academic and commercial implications. Appetite 2016, 107, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hartmann, C.; Siegrist, M. Development and validation of the Food Disgust Scale. Food Qual. Preference 2018, 63, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodenheimer, F.S. Insects as Human Food: A Chapter of the Ecology of Man; Dr W Junk Publisher: The Huage, The Netherlands, 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Looy, H.; Dunkel, F.V.; Wood, J.R. How then shall we eat? Insect-eating attitudes and sustainable foodways. Agric. Hum. Values 2014, 31, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Elorduy, J. Anthropo-entomophagy: Cultures, evolution and sustainability. Entomol. Res. 2009, 39, 271–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, C.; Shi, J.; Giusto, A.; Siegrist, M. The psychology of eating insects: A cross-cultural comparison between Germany and China. Food Qual. Prefer. 2015, 44, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruby, M.B.; Rozin, P.; Chan, C. Determinants of willingness to eat insects in the USA and India. J. Insects Food Feed 2015, 1, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondoc, I. The Veterinary Sanitary Control of Fish and Fisheries Products. In Control of Products and Food of Animal Origin (Controlul Produselor Și Alimentelor de Origine Animală—Original Title); Ion Ionescu de la Brad, Iași Publishing: Iași, Romania, 2014; Volume I, pp. 264–346. ISBN 978-973-147-139-6. [Google Scholar]

- Bondoc, I.; Șindilar, E.V. Veterinary Sanitary Control of Food Quality and Hygiene (Controlul Sanitar Veterinar al Calității Și Salubrității Alimentelor—Original Title); Ion Ionescu de la Brad, Iaşi Publishing: Iași, Romania, 2002; Volume I, pp. 151–166. ISBN 973-8014-64-6. [Google Scholar]

- Caparros Megido, R.; Sablon, L.; Geuens, M.; Brostaux, Y.; Alabi, T.; Blecker, C.; Drugmand, D.; Haubruge, É.; Francis, F. Edible Insects Acceptance by Belgian Consumers: Promising Attitude for Entomophagy Development. J. Sens. Stud. 2014, 29, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govorushko, S. Global status of insects as food and feed source: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 91, 436–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, C.; Siegrist, M. Consumer perception and behaviour regarding sustainable protein consumption: A systematic review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 61, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.S.G. Eating Insects: Consumer Acceptance of a Culturally Inappropriate Food; Wageningen University: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tani, Y.; Hashimoto, S.; Ochiai, M. What makes rural, traditional, cultures more sustainable? Implications from conservation efforts in mountainous rural communities of Japan. Landsc. Res. 2016, 41, 892–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrello, M.; Caracciolo, F.; Lombardi, A.; Pascucci, S.; Cembalo, L. Consumers’ Perspective on Circular Economy Strategy for Reducing Food Waste. Sustainability 2017, 9, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gasco, L.; Biancarosa, I.; Liland, N.S. From waste to feed: A review of recent knowledge on insects as producers of protein and fat for animal feeds. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2020, 23, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbeke, W.; Spranghers, T.; De Clercq, P.; De Smet, S.; Sas, B.; Eeckhout, M. Insects in animal feed: Acceptance and its determinants among farmers, agriculture sector stakeholders and citizens. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2015, 204, 72–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsi, L.; Voege, L.L.; Stranieri, S. Eating edible insects as sustainable food? Exploring the determinants of consumer acceptance in Germany. Food Res. Int. 2019, 125, 108573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiemer, C.; Halloran, A.; Jespersen, K.; Kaukua, P. Marketing Insects: Superfood or Solution-Food? In Edible Insects in Sustainable Food Systems; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 213–236. ISBN 978-3-319-74011-9. [Google Scholar]

- de Boer, J.; Schösler, H.; Boersema, J.J. Motivational differences in food orientation and the choice of snacks made from lentils, locusts, seaweed or “hybrid” meat. Food Qual. Prefer. 2013, 28, 32–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.S.G.; House, J. Consumer Acceptance of Insects as Food: Integrating Psychological and Socio-cultural Perspectives. In Edible Insects in Sustainable Food Systems; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.S.G.; Tibboel, C.J.; Stieger, M. Why do unusual novel foods like insects lack sensory appeal? Investigating the underlying sensory perceptions. Food Qual. Preference 2017, 60, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa-Neto, E.M.; Dunkel, F. Insects as Food: History, Culture, and Modern Use around the World. In Insects as Sustainable Food Ingredients—Production, Processing and Food Applications; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 29–60. ISBN 978-0-12-802856-8. [Google Scholar]

- Caparros Megido, R.; Haubruge, É.; Francis, F. Insects, the next European Foodie Craze? In Edible Insects in Sustainable Food Systems; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 353–361. ISBN 978-3-319-74011-9. [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann, C.; Siegrist, M. Becoming an insectivore: Results of an experiment. Food Qual. Prefer. 2016, 51, 118–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gmuer, A.; Guth, J.N.; Hartmann, C.; Siegrist, M. Effects of the degree of processing of insect ingredients in snacks on expected emotional experiences and willingness to eat. Food Qual. Prefer. 2016, 54, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lensvelt, E.; Steenbekkers, L.P.A. Exploring Consumer Acceptance of Entomophagy: A Survey and Experiment in Australia and the Netherlands. Ecol. Food Nutr. 2014, 53, 543–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menozzi, D.; Sogari, G.; Veneziani, M.; Simoni, E.; Mora, C. Eating novel foods: An application of the Theory of Planned Behaviour to predict the consumption of an insect-based product. Food Qual. Preference 2017, 59, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meixner, O.; von Pfalzen, L.M. Die Akzeptanz von Insekten in Der Ernährung: Eine Studie Zur Vermarktung von Insekten Als Lebensmittel Aus Konsumentensicht; Springer: Heidelberg/Berlin, Germany, 2018; ISBN 3-658-21336-1. [Google Scholar]

- Piha, S.; Pohjanheimo, T.; Lähteenmäki-Uutela, A.; Křečková, Z.; Otterbring, T. The effects of consumer knowledge on the willingness to buy insect food: An exploratory cross-regional study in Northern and Central Europe. Food Qual. Prefer. 2018, 70, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shockley, M.; Dossey, A.T. Insects for Human Consumption. In Mass Production of Beneficial Organisms: Invertebrates and Entomopathogens; Academic Press: London, UK, 2013; pp. 617–652. ISBN 0-12-391415-9. [Google Scholar]

- Sogari, G.; Menozzi, D.; Mora, C. Exploring young foodies’ knowledge and attitude regarding entomophagy: A qualitative study in Italy. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2017, 7, 16–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.S.G.; Fischer, A.R.; Tinchan, P.; Stieger, M.; Steenbekkers, L.; van Trijp, H.C. Insects as food: Exploring cultural exposure and individual experience as determinants of acceptance. Food Qual. Prefer. 2015, 42, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Huis, A.; Van Itterbeeck, J.; Klunder, H.; Mertens, E.; Halloran, A.; Muir, G.; Vantomme, P. Edible Insects: Future Prospects for Food and Feed Security; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO): Rome, Italy, 2013; ISBN 92-5-107596-4. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, H.S.G.; Fischer, A.R.; van Trijp, H.C.; Stieger, M. Tasty but nasty? Exploring the role of sensory-liking and food appropriateness in the willingness to eat unusual novel foods like insects. Food Qual. Prefer. 2016, 48, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Thielen, L.; Vermuyten, S.; Storms, B.; Rumpold, B.; Van Campenhout, L. Consumer acceptance of foods containing edible insects in Belgium two years after their introduction to the market. J. Insects Food Feed 2019, 5, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verneau, F.; Caracciolo, F.; Coppola, A.; Lombardi, P. Consumer fears and familiarity of processed food. The value of information provided by the FTNS. Appetite 2014, 73, 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verneau, F.; La Barbera, F.; Kolle, S.; Amato, M.; Del Giudice, T.; Grunert, K. The effect of communication and implicit associations on consuming insects: An experiment in Denmark and Italy. Appetite 2016, 106, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, M.A.; Shin, J.T.; Kim, Y.W. Customer Acceptance, Barriers, and Preferences in the US. In Edible Insects in Sustainable Food Systems; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 387–399. ISBN 978-3-319-74011-9. [Google Scholar]

- Gamborg, C.; Röcklinsberg, H.; Gjerris, M. Sustainable Proteins? Values Related to Insects in Food Systems. In Edible Insects in Sustainable Food Systems; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostecka, J.; Konieczna, K.; Cunha, L. Evaluation of insect-based food acceptance by representatives of polish consumers in the context of natural resources processing retardation. J. Ecol. Eng. 2017, 18, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dossey, A.T.; Tatum, J.T.; McGill, W.L. Modern Insect-Based Food Industry: Current Status, Insect Processing Technology, and Recommendations Moving Forward. In Insects as Sustainable Food Ingredients; Dossey, A.T., Morales-Ramos, J.A., Rojas, M.G., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2016; pp. 113–152. ISBN 978-0-12-802856-8. [Google Scholar]

- La Barbera, F.; Verneau, F.; Amato, M.; Grunert, K. Understanding Westerners’ disgust for the eating of insects: The role of food neophobia and implicit associations. Food Qual. Prefer. 2018, 64, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallo, C.; Materia, V.C. Insects or Not Insects? Dilemmas or Attraction for Young Generations: A Case in Italy. Int. J. Food Syst. Dyn. 2018, 9, 226–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteleone, E.; Spinelli, S.; Dinnella, C.; Endrizzi, I.; Laureati, M.; Pagliarini, E.; Sinesio, F.; Gasperi, F.; Torri, L.; Aprea, E.; et al. Exploring influences on food choice in a large population sample: The Italian Taste project. Food Qual. Preference 2017, 59, 123–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gere, A.; Székely, G.; Kovács, S.; Kókai, Z.; Sipos, L. Readiness to adopt insects in Hungary: A case study. Food Qual. Prefer. 2017, 59, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlup, Y.; Brunner, T. Prospects for insects as food in Switzerland: A tobit regression. Food Qual. Prefer. 2018, 64, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, K.; Muhlhausler, B.; Motley, C.; Crump, A.; Bray, H.; Ankeny, R. Australian Consumers’ Awareness and Acceptance of Insects as Food. Insects 2018, 9, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Meehan, J.; Simonetto, M.; Montan, L.; Goodin, C. Pricing and Profitability Management: A Practical Guide for Business Leaders; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-0-470-82705-5. [Google Scholar]

- Lambin, J.-J.; Ostillio, M.C. Marketing; McGraw-Hill Education: Milan, Spain, 1991; ISBN 88-386-0626-9. [Google Scholar]

- Shoemaker, S.; Lewis, R.C.; Yesawich, P.C.; Chambers, R.E. Marketing Leadership in Hospitality and Tourism: Strategies and Tactics for Competitive Advantage; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2007; ISBN 0-13-118240-4. [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenstein, D.R.; Ridgway, N.M.; Netemeyer, R.G. Price Perceptions and Consumer Shopping Behavior: A Field Study. J. Mark. Res. 1993, 30, 234–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A.; Bitner, M.J.; Gremler, D.D. Services Marketing: Integrating Customer Focus across the Firm; McGraw-Hill Education: London, UK, 2018; ISBN 0-07-811210-9. [Google Scholar]

- Wathieu, L.; Bertini, M. Price as a Stimulus to Think: The Case for Willful Overpricing. Mark. Sci. 2007, 26, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Monroe, K.B. Buyers’ Subjective Perceptions of Price. J. Mark. Res. 1973, 10, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E.W. Customer satisfaction and price tolerance. Mark. Lett. 1996, 7, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- East, R.; Singh, J.; Wright, M.; Vanhuele, M. Consumer Behaviour: Applications in Marketing; SAGE: London, UK, 2016; ISBN 978-1-4739-1935-8. [Google Scholar]

- Tully, S.M.; Winer, R.S. The Role of the Beneficiary in Willingness to Pay for Socially Responsible Products: A Meta-analysis. J. Retail. 2014, 90, 255–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, A.R.; Monroe, K.B. The Moderating Effect of Prior Knowledge on Cue Utilization in Product Evaluations. J. Consum. Res. 1988, 15, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, L.R.; Goldsmith, R.E. A Short, Reliable Measure of Subjective Knowledge. J. Bus. Res. 1999, 46, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selnes, F. Subjective and Objective Measures of Product Knowledge Contrasted. ACR N. Am. Adv. 1986, 13, 67–71. [Google Scholar]

- Park, C.W.; Mothersbaugh, D.L.; Feick, L. Consumer Knowledge Assessment. J. Consum. Res. 1994, 21, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, N.; Dodd, T.; Ghiselli, R. Capturing the Younger Wine Consumer. J. Wine Res. 2008, 19, 123–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodd, T.H.; Laverie, D.A.; Wilcox, J.F.; Duhan, D.F. Differential Effects of Experience, Subjective Knowledge, and Objective Knowledge on Sources of Information used in Consumer Wine Purchasing. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2005, 29, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raju, P.; Lonial, S.C.; Mangold, W.G. Differential Effects of Subjective Knowledge, Objective Knowledge, and Usage Experience on Decision Making: An Exploratory Investigation. J. Consum. Psychol. 1995, 4, 153–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, T.-I. Objective knowledge, subjective knowledge, and prior experience of organic cotton apparel. Fash. Text. 2019, 6, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, S.; Kallas, Z. Meta-analysis of consumers’ willingness to pay for sustainable food products. Appetite 2021, 163, 105239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, K.M.; Hofstetter, R.; Krohmer, H.; Zhang, Z.J. How Should Consumers’ Willingness to Pay be Measured? An Empirical Comparison of State-of-the-Art Approaches. J. Mark. Res. 2011, 48, 172–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabor, A.; Granger, C.W.J. Pricing, Principles and Practices; Heinemann Educational Publishers: Portsmouth, NH, USA, 1977; ISBN 0-435-84365-6. [Google Scholar]

- Train, K.E. Discrete Choice Methods with Simulation; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009; ISBN 1-139-48037-5. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstetter, R.; Miller, K.M.; Krohmer, H.; Zhang, Z.J. A de-biased direct question approach to measuring consumers’ willingness to pay. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2020, 38, 70–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipovetsky, S.; Magnan, S.; Zanetti-Polzi, A. Pricing Models in Marketing Research. Intell. Inf. Manag. 2011, 3, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sattler, H.; Nitschke, T. Ein empirischer Vergleich von Instrumenten zur Erhebung von Zahlungsbereitschaften. Schmalenbachs Z. Für Betr. Forsch. 2003, 55, 364–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloss, D.; Kunter, M. The van westendorp price-sensitivity meter as a direct measure of willingness-to-pay. Eur. J. Manag. 2016, 16, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maes, S.; Vingerhoets, A.; Van Heck, G. The study of stress and disease: Some developments and requirements. Soc. Sci. Med. 1987, 25, 567–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gellynck, X.; Viaene, J. Market-orientated Positioning of On-farm Processed Foods as a Condition for Successful Farm Diversification. J. Agric. Econ. 2002, 53, 531–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmon, R.; Raffo, D.; Faulk, S. Incorporating price sensitivity measurement into the software engineering process. In Proceedings of the PICMET’03: Portland International Conference on Management of Engineering and Technology Technology Management for Reshaping the World, Portland, OR, USA, 20–24 July 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naranjo-Guevara, N.; Fanter, M.; Conconi, A.M.; Floto-Stammen, S. Consumer acceptance among Dutch and German students of insects in feed and food. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 9, 414–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eumofa. The Eu Fish Market—2020 Edition; Eumofa: Luxembourg, 2020; ISBN 978-92-76-15377-1. [Google Scholar]

- Harmon, R.R.; Unni, R.; Anderson, T.R. Price Sensitivity Measurement and New Product Pricing: A Cognitive Response Approach. In Proceedings of the PICMET’07-2007 Portland International Conference on Management of Engineering & Technology, Portland, OR, USA, 5–9 August 2007; pp. 1961–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çolak, O.; Koşan, L. Price Sensitivity Measurement: A Yield Management Approach. Istanb. Bus. Res. 2021, 50, 47–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazoche, P.; Poret, S. Acceptability of insects in animal feed: A survey of French consumers. J. Consum. Behav. 2020, 20, 251–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISTAT Aspects of Daily Life—People. Available online: http://dati.istat.it/Index.aspx?QueryId=16813 (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Monroe, K.B. The Influence of Price on Product Perceptions and Product Choice. Adv. Consum. Res. 1982, 9, 206–209. [Google Scholar]

- White, R.R.; Brady, M. Can consumers’ willingness to pay incentivize adoption of environmental impact reducing technologies in meat animal production? Food Policy 2014, 49, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zander, K.; Feucht, Y. Consumers’ Willingness to Pay for Sustainable Seafood Made in Europe. J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark. 2018, 30, 251–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Almeida, C.; Altintzoglou, T.; Cabral, H.; Vaz, S.G. Does seafood knowledge relate to more sustainable consumption? Br. Food J. 2015, 117, 894–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donoghue, S.; Wilken-Jonker, I.; Steffens, F.E.; Kirsten, J.F. South African consumers’ willingness to pay a premium for Karoo Lamb: The influence of subjective and objective knowledge, label information and demographics. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 63, 102664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosenko, R.; Rahtz, D. Buyer Market Price Knowledge Influence on Acceptable Price Range and Price Limits. ACR N. Am. Adv. 1988, 15, 328–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E.M. Diffusion of Innovations; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Peschel, A.; Grebitus, C.; Steiner, B.; Veeman, M. How does consumer knowledge affect environmentally sustainable choices? Evidence from a cross-country latent class analysis of food labels. Appetite 2016, 106, 78–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Popoff, M.; MacLeod, M.; Leschen, W. Attitudes towards the use of insect-derived materials in Scottish salmon feeds. J. Insects Food Feed 2017, 3, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sogari, G.; Menozzi, D.; Mora, C.; Gariglio, M.; Gasco, L.; Schiavone, A. How information affects consumers’ purchase intention and willingness to pay for poultry farmed with insect-based meal and live insects. J. Insects Food Feed 2022, 8, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menozzi, D.; Sogari, G.; Mora, C.; Gariglio, M.; Gasco, L.; Schiavone, A. Insects as Feed for Farmed Poultry: Are Italian Consumers Ready to Embrace This Innovation? Insects 2021, 12, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altmann, B.A.; Risius, A.; Anders, S. Feeds of the Future: A Choice Experiment of Chicken Breast Produced with Micro-Algae or Insect Meal. In Proceedings of the 59th Annual Conference of the German Society of Economic and Social Sciences in Agriculture, Braunschweig, Germany, 25–27 September 2019; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronnmann, J.; Hoffmann, J. Consumer preferences for farmed and ecolabeled turbot: A North German perspective. Aquac. Econ. Manag. 2018, 22, 342–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronnmann, J.; Asche, F. Sustainable Seafood From Aquaculture and Wild Fisheries: Insights From a Discrete Choice Experiment in Germany. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 142, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spartano, S.; Grasso, S. Consumers’ Perspectives on Eggs from Insect-Fed Hens: A UK Focus Group Study. Foods 2021, 10, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maesano, G.; Di Vita, G.; Chinnici, G.; Pappalardo, G.; D’Amico, M. The Role of Credence Attributes in Consumer Choices of Sustainable Fish Products: A Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanigro, M.; McCluskey, J.J.; Goemans, C. The Economics of Nested Names: Name Specificity, Reputations, and Price Premia. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2010, 92, 1339–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mauracher, C.; Tempesta, T.; Vecchiato, D. Consumer preferences regarding the introduction of new organic products. The case of the Mediterranean sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax) in Italy. Appetite 2013, 63, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asche, F.; Larsen, T.A.; Smith, M.; Sogn-Grundvåg, G.; Young, J.A. Pricing of eco-labels with retailer heterogeneity. Food Policy 2015, 53, 82–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roheim, C.A.; Asche, F.; Santos, J.I. The Elusive Price Premium for Ecolabelled Products: Evidence from Seafood in the UK Market. J. Agric. Econ. 2011, 62, 655–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicia, G.; Furno, M.; Del Giudice, T. Do Consumers’ Values and Attitudes Affect Food Retailer Choice? Evidence from a National Survey on Farmers’ Market in Germany. Agric. Food Econ. 2021, 9, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokthi, E.; Canco, I.; Topulli, E. Whose Salad Is Organic? An Attribute Segmentation Perspective-Evidence from Albania. Econ. Agro-Aliment. Food Econ. 2021, 23, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marangon, F.; Troiano, S.; Carzedda, M.; Nassivera, F. Consumers’ Acceptance of Genome Edited Food and the Role of Information. Ital. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2021, 76, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total n = 318 | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 165 | 51.7 |

| Female | 153 | 47.9 |

| Age | ||

| 18–29 | 45 | 14.1 |

| 30–39 | 56 | 17.5 |

| 40–49 | 136 | 42.6 |

| 50–59 | 55 | 17.2 |

| ≥60 | 26 | 8.1 |

| Education | ||

| Lower middle school | 11 | 3.4 |

| High school | 91 | 28.5 |

| University | 122 | 38.2 |

| Post University | 94 | 29.5 |

| Occupation | ||

| Freelance | 61 | 19.1 |

| Desk Job | 42 | 13.2 |

| Student | 41 | 12.8 |

| Private employee | 40 | 12.5 |

| Researcher/University Professor | 39 | 12.2 |

| Non-university Teacher | 30 | 9.4 |

| Government job | 20 | 6.3 |

| Pensioner | 13 | 4.1 |

| Entrepreneur | 11 | 3.4 |

| Unemployed | 10 | 3.1 |

| Artisan | 6 | 1.9 |

| Househusband/housewife | 3 | 0.9 |

| Not answered | 2 | 0.6 |

| Cleric | 1 | 0.3 |

| Subject knowledge | ||

| I have heard of the eating of insects, and I know what it means | 181 | 56.7 |

| I have heard of the eating of insects but actually don’t know what it means | 103 | 32.3 |

| No, I have never heard of the eating of insects | 34 | 10.7 |

| Price Points and Ranges | Total Respondents | High SK Respondents |

|---|---|---|

| Point of marginal cheapness (PMC) | 6.50 | 6.75 |

| Point of marginal expensiveness (PME) | 13.5 | 14.50 |

| Optimal price point (OPP) | 7.50 | 8.00 |

| Indifference price point (IPP) | 10.00 | 10.5 |

| Range of acceptable price (RAP) | 6.00 | 7.75 |

| Range of relatively cheap price (RRCP) | 3.50 | 3.75 |

| Range of relatively expensive price (RREP) | 3.50 | 4.00 |

| Range of stress price (RSP) | 2.50 | 2.50 |

| Stress factor (SF) | 0.36 | 0.32 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Arru, B.; Furesi, R.; Pulina, P.; Madau, F.A. Price Sensitivity of Fish Fed with Insect Meal: An Analysis on Italian Consumers. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6657. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116657

Arru B, Furesi R, Pulina P, Madau FA. Price Sensitivity of Fish Fed with Insect Meal: An Analysis on Italian Consumers. Sustainability. 2022; 14(11):6657. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116657

Chicago/Turabian StyleArru, Brunella, Roberto Furesi, Pietro Pulina, and Fabio A. Madau. 2022. "Price Sensitivity of Fish Fed with Insect Meal: An Analysis on Italian Consumers" Sustainability 14, no. 11: 6657. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116657

APA StyleArru, B., Furesi, R., Pulina, P., & Madau, F. A. (2022). Price Sensitivity of Fish Fed with Insect Meal: An Analysis on Italian Consumers. Sustainability, 14(11), 6657. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116657