Framing the Values of Vernacular Architecture for a Value-Based Conservation: A Conceptual Framework

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methodology

3. Value, Value Typology and Value Assessment: A Rapid Literature Review

3.1. The Idea of Value Typologies

3.2. Associative Challenges of Value Typologies

3.3. Proposed Alternatives to Value Typologies?

3.4. The Case for Valuing Vernacular Architecture

4. Conceptual Framing and Framework Development

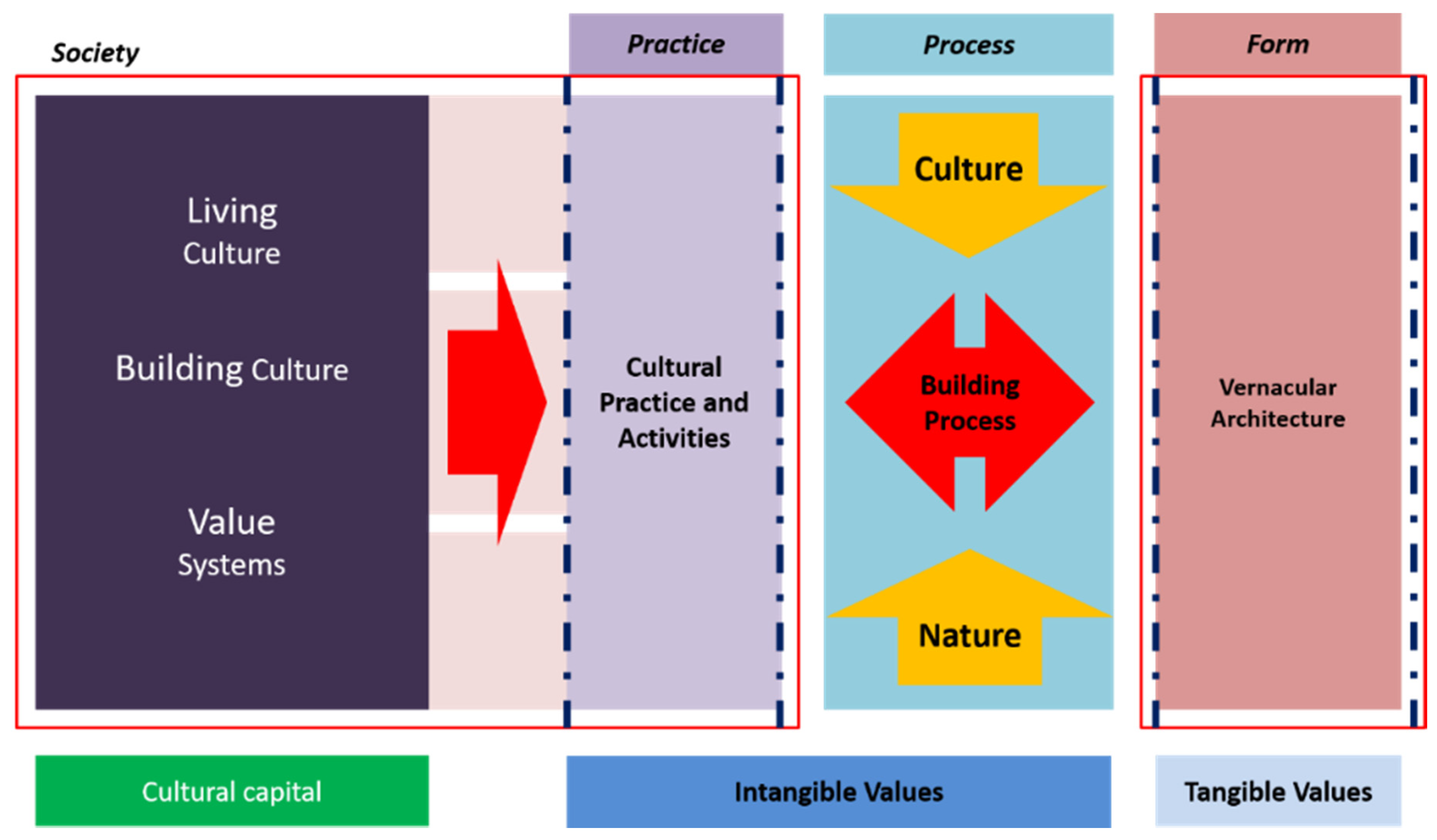

4.1. Guiding Contexts for Valuing Vernacular Architecture: The Practice, Process and the Form

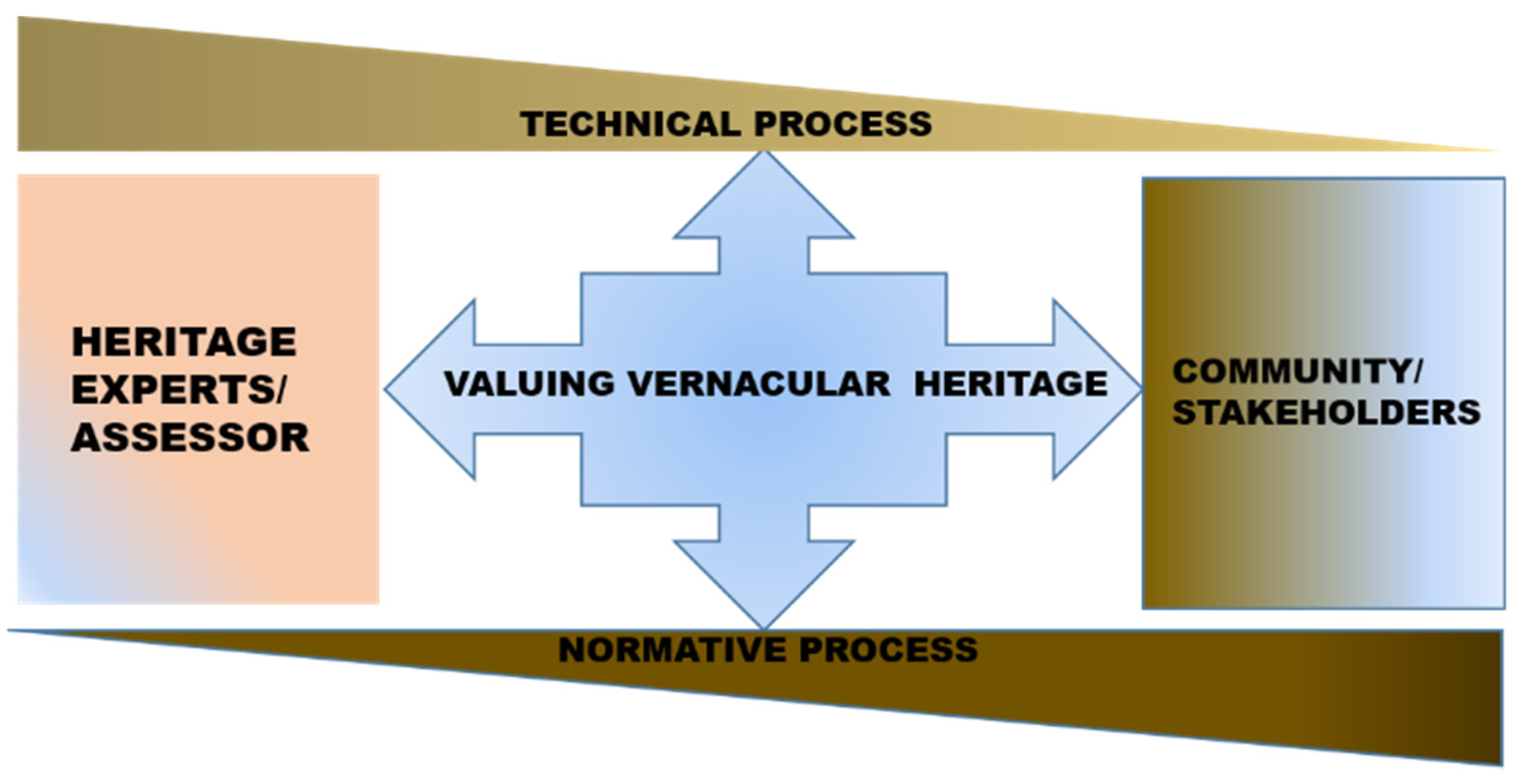

4.2. Approach to Assessing Vernacular Value Characterizations

5. Results and Discussion: Developing the Vernacular Value Model (VVM)

6. Conclusions and Recommendation

- Presents a robust and coherent characterization for the values of vernacular architecture.

- Abandons determinism and aims at discovering the unknown value rather than inquire for values through the preconceived list of academic value typologies.

- Premises approach to the ‘when’ and ‘how’ of creating synergies between the perceptions of values according to disciplinary experts and community members to address the complexities and nuanced dimensions of value in vernacular architecture.

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cassar, M. Sustainable Heritage: Challenges and Strategies for the Twenty-First Century. APT Bulletin. J. Preserv. Technol. 2009, 40, 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Avrami, E.; Macdonald, S.; Mason, R.; Myers, D. Introcution. In Values in Heritage Management: Emerging Approaches and Research Directions; Avrami, E., Macdonald, S., Mason, R., Myers, D., Eds.; Getty Conservation Institute: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2019; Available online: http://openarchive.icomos.org/id/eprint/2384/1/9781606066195.pdf (accessed on 23 April 2021).

- Fredheim, H.; Khalaf, M. The significance of values: Heritage value typologies re-examined. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2016, 22, 466–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stovel, H. A significance-driven approach to the development of the historic structure report. APT Bull. J. Preserv. Technol. 1997, 28, 45–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, R. Assessing values in conservation planning: Methodological issues and choices. In Assessing the Values of Cultural Heritage; de la Torre, M., Ed.; Getty Conservation Institute: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2002; pp. 5–30. [Google Scholar]

- Affelt, W.J. Technitas method for assessment of the values attributed to cultural heritage of technology. In How to Assess Built Heritage? Assumptions, Methodologies, Examples of Heritage Assessment Systems; Szmygin, B., Ed.; International Scientific Committee for Theory and Philosophy of Conservation and Restoration ICOMOS Romualdo Del Bianco Foundatione Lublin University of Technology Florence: Lublin, Poland, 2015; ISBN 978-83-940280-3-9. [Google Scholar]

- De la Torre, M.; Mason, R. Introduction. In Assessing the Values of Cultural Heritage; Getty Conservation Institute: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2002; pp. 3–4. [Google Scholar]

- Satterfield, T. Numbness and sensitivity in the elicitation of environmental values. In Assessing Values in Heritage Conservation; de la Torre, M., Ed.; Getty Conservation Institute: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2002; pp. 77–99. [Google Scholar]

- Riegl, A. The Modern Cult of Monuments: Its Character and Its Origin. Oppositions 1982, 25, 21–51. [Google Scholar]

- Lipe, W.D. Value and Meaning in Cultural Resources. In Approaches to the Archaeological Heritage: A Comparative Study of World Cultural Resource Management Systems; Cleere, H., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1984; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- English Heritage. Conservation Principles: Policies and Guidance for the Sustainable Management of the Historic Environment; English Heritage: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- ICOMOS Australia. The Australian ICOMOS Charter for the Conservation of Places of Cultural Significance (The Burra Charter); ICOMOS Australia: Sydney, Australia, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Frey, B.S. The Evaluation of Cultural Heritage: Some Critical Issues. In Economic Perspectives on Cultural Heritage; Hutter, M., Rizzo, I., Eds.; St. Martin’s Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Ashley-Smith, J. Risk Assessment for Object Conservation; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Rudolff, B. Intangible” and “Tangible” Heritage: A Topology of Culture in Contexts of Faith. Ph.D. Thesis, Institute of Geography, and Faculty for Chemistry, Pharmacy and Geo-Sciences (09), Johannes Gutenberg-University of Mainz, Mainz, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lamprakos, M. Riegl’s Modern Cult of Monuments and the Problem of Value. Chang. Over Time 2014, 4, 418–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navrud, S. Willingness to Pay for Preservation of Species—An Experiment with Actual Payments. In Pricing the European Environment. Oslo; Navrud, S., Ed.; Scandinavian University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1992; pp. 231–246. [Google Scholar]

- Powe, N.A.; Willis, K.G. Benefits received by visitors to heritage sites: A case study of Warkworth Castle. Leis. Stud. 1996, 15, 259–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, R.T.; Mitchell, R.C.; Conaway, M.B. Economic benefits to foreigners visiting Morocco accruing from the rehabilitation of the Fes Medina. In Valuing Cultural Heritage: Applying Environmental Valuation Techniques to Historic Buildings, Monuments and Artifacts; Navrud, S., Ready, R.C., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Northampton, UK, 2002; Volume 1, pp. 18–41. [Google Scholar]

- Salazar SD, S.; Marques, J.M. Valuing cultural heritage: The social benefits of restoring and old Arab tower. J. Cult. Herit. 2005, 6, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICOMOS. Charter on the Built Vernacular Heritage. 1999. Available online: www.international.icomos.org/charters.htm (accessed on 7 April 2018).

- Daniel, M. Crossing Boundaries: Revisiting the Thresholds of Vernacular Architecture. Vernac. Archit. 2010, 41, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crinson, M.; Dynamic Vernacular—An Introduction. ABE J. Archit. Beyond Eur. 2016. Available online: https://journals.openedition.org/abe/3002 (accessed on 12 March 2019).

- Oliver, P. Built to Meet Needs: Cultural Issues in Vernacular Architecture; Oxford Architectural Press: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Aysan, Y. An Understanding of the Vernacular Discourse. Ph.D. Thesis, Oxford Polytechnic, Oxford, UK, 1988. Unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Robert, P.; Alain, R. Dictionnaire Alphabétique et Analogique de la Langue Française, 2nd ed.; Le Robert: Paris, France, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Özkan, S.; Turan, M.; Üstünkök, O. Institutionalized Architecture, Vernacular Architecture and Vernacularism in Historical Perspective. METU J. Fac. Archit. 1979, 5, 127–156. [Google Scholar]

- Frey, P. Learning from Vernacular: Towards a New Vernacular Architecture; Actes Sud: Arles, France, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, P. Changing ideals in Modern Architecture; Faber and Faber: London, UK, 1965; pp. 122–123. [Google Scholar]

- Guillaud, H. Defining vernacular architecture. In Versus Heritage for Tomorrow. Vernacular Knowledge for Sustainable Architecture; Correia, M., Dipasquale, L., Mecca, S., Eds.; Firenze University Press: Florence, Italy, 2014; pp. 32–33. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/54599448.pdf (accessed on 9 September 2019).

- Oliver, P. Handed Down Architecture: Tradition and Transmission. In Dwellings, Settlements and Tradition: Cross-Cultural Perspectives; Bourdier, J., AISayyad, N., Eds.; University Press of America: Lanham, MD, USA, 1989; pp. 53–76. [Google Scholar]

- Highlands, D. What’s Indigenous? An Essay on Building. In Vernacular Architecture: Paradigms of Environmental Response; Turan, M., Ed.; Avebury: Aldershot, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Noonan, D.S. Contingent Valuation Studies in the Arts and Culture: An Annotated Bibliography; Working Paper 11; University of Chicago Cultural Policy Center: Chicago, IL, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Noonan, D.S. Contingent valuation and cultural resources: A meta-analytic review of literature. J. Cult. Econ. 2003, 27, 159–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Krippendorff, K. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, C. Practical Research Methods: A User-Friendly Guide to Mastering Research Techniques and Projects; How to Books Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Low, S.M. Anthropological-ethnographic Methods for the Assessment of Cultural Values in Heritage Conservation. In Assessing the Values of Cultural Heritage; De la Torre, M., Ed.; Getty Conservation Institute: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2002; pp. 31–49. [Google Scholar]

- Avrami, E.C.; Mason, R.; De la Torre, M. Values and Heritage Conservation: Research Report; Getty Conservation Institute: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Munjeri, D. The Unknown Dimension: An Issue of Values. Proceedings of 14th ICOMOS General Assembly and International Symposium: ‘Place, Memory, Meaning: Preserving Intangible Values in Monuments and Sites’, Victoria Falls, Zimbabwe, 27–31 October 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, R.; Avrami, E. Heritage Values and Challenges of Conservation Planning. In Management Planning for Archaeological Sites: An International Workshop Organized; Teutonico, J.M., Palumbo, G., Eds.; Getty Conservation Institute: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2000; pp. 13–26. [Google Scholar]

- Australia ICOMOS. The Australia ICOMOS Guidelines for the Conservation of Places of Cultural Significance (‘Burra Charter’). 1979. Available online: http://australia.icomos.org/wp-content/uploads/Burra-Charter_1979.pdf (accessed on 17 March 2020).

- Walton, T. Assessing the Archaeological Values of Historic Places: Procedures, Methods and Field Techniques; Department of Conservation: Wellington, New Zealand, 1999; Volume 167. [Google Scholar]

- Worthing, D.; Bond, S. Managing Built Heritage: The Role of Cultural Significance; Wiley-Blackwell: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira Roders, A.A.; van Oers, R. Managing change: Integrating impact assessments in heritage conservation. In Understanding heritage: Perspectives in Heritage Studies; Albert, M.-T., Bernecker, R., Rudolff, B., Eds.; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany; Volume 1, p. 89.

- Australia ICOMOS. Burra Charter Guideline—Cultural Significance; Australia ICOMOS: Burwood, Australia, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Heritage Collections Council. Significance: A Guide to Assessing the Significance of Cultural Heritage Objects and Collections; Commonwealth of Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- English Heritage. Sustaining the Historic Environment: New Perspectives on the Future. English Heritage Discussion Document; English Heritage: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- ICOMOS New Zealand. ICOMOS New Zealand Charter for the Conservation of Places of Cultural Heritage Value. ICOMOS New Zealand. Auckland. 2010. Available online: http://www.icomos.org.nz/docs/NZ_Charter.pdf (accessed on 17 March 2016).

- Pye, E. Caring for the Past: Issues in Conservation for Archaeology and Museums; James and James: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Caple, C. The Aims of Conservation. In Conservation: Principles, Dilemmas and Uncomfortable Truths; Richmond, A., Bracker, A., Eds.; Butterworh-Heinemann: London, UK, 2009; pp. 25–31. [Google Scholar]

- Appelbaum, B. Conservation Treatment Methodology; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Yung, E.H.; Chan, E.H. Implementation challenges to the adaptive reuse of heritage buildings: Towards the goals of sustainable, low carbon cities. Habitat Int. 2012, 3, 352–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gielen, P.; Elkhuizen, S.; van der Hoogen, Q.; Lijster, T.; Otte, H. De Waarde Van Cultuur. Onderzoekscentrum Arts in Society; Rijksuniversiteit Groningen: Brussels, Belgium, 2014; Available online: http://www.kunsten.be/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/Rapport-De-Waarde-van-Cultuur.pdf (accessed on 2 April 2018).

- Fusco, G.L. Risorse Architettoniche e Culturali: Valutazioni e Strategie di Conservazione; Franco Angeli: Milano, Italy, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Fusco, G.L.; Nijkamp, P. Le Valutazioni per lo Sviluppo Sostenibile Della Città e del Territorio; Franco Angeli: Milano, Italy, 1997; ISBN 978-88-464-0182-3. [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson, J. The Cultural Values Model: An integrated approach to values in landscapes. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2008, 84, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, N. From Values to Narrative: A New Foundation for the Conservation of Historic Buildings. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2013, 20, 634–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulios, I. Moving beyond a Values-based Approach to Heritage Conservation. Conserv. Manag. Archaeol. Sites 2010, 12, 170–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, K.E. Nara Document on Authenticity. In Proceedings of the Nara Conference on Authenticity in relation to the World Heritage Convention, Nara, Japan, 1–6 November 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Emerick, K. Conserving and Managing Ancient Monuments: Heritage, Democracy, and Inclusion; Heritage Matters Series; Boydell & Brewer Press: Suffolk, England, 2014; p. 14. [Google Scholar]

- Sully, D. Colonising and Conservation. In Decolonising Conservation: Caring for Maori Meeting Houses outside New Zealand; Sully, D., Ed.; Left Coast Press: Walnut Creek, CA, USA, 2007; pp. 27–43. [Google Scholar]

- Abu-Khafajah, S.; Rababeh, S. The Silence of Meanings in Conventional Approaches to Cultural Heritage in Jordan: The Exclusion of Contexts and the Marginalization of the Intangible. In Safeguarding Intangible Cultural Heritage; Heritage Matters Series; Stefano, M.L., Davis, P., Corsane, G., Eds.; Boydell Press: Woodbridge, UK, 2012; pp. 71–83. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence, D.P. Impact significance determination—back to basics. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2007, 27, 755–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, A. Values. In Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy; Edward Craig: London, UK; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1998; Volume 9, pp. 581–583. [Google Scholar]

- Swaffield, S.; Foster, R. Community Perceptions of Landscape Values in the South Island High Country; Department of Conservation: Wellington, New Zealand, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Carver, M. On Archaeological Value. Antiquity 1996, 70, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Throsby, D. Economics and Culture; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Feilden, B. Conservation of Historic Buildings; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Keene, S. Fragments of the World: Uses of Museum Collections; Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Orbaşlı, A. Architectural Conservation: Principles and Practice; Blackwell Science: Oxford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Stubbs, J.H. Time Honored: A Global View of Architectural Conservation; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez, R.L. A Methodological Approach towards Conservation. Conserv. Manag. Archaeol. Sites 2010, 12, 146–169. [Google Scholar]

- Szmelter, I. A New Conceptual Framework for the Preservation of the Heritage of Modern Art. In Theory and Practice in the Conservation of Modern and Contemporary Art: Reflections on the Roots and the Perspectives; Schädler-Saub, U., Weyer, A., Eds.; Archetype: London, UK, 2010; pp. 33–49. [Google Scholar]

- Rössler, N.M.; Tricaud, P.M.; World Heritage Cultural Landscapes. A Handbook for Conservation and Management. Available online: http://whc.UNESCO.org/documents/publi_wh_articles_26_en.pdf (accessed on 26 December 2019).

- Rössler, N.M. UNESCO and cultural landscape protection. In Cultural Landscapes of Universal Value—Components of a Global Strategy; von Droste, B., Plachter, H., Rössler, M., Eds.; Gustav Fischer in Cooperation with UNESCO: Jena, Germany, 1995; pp. 42–49. [Google Scholar]

- Heath, K. Vernacular Architecture and Regional Design; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- AA.VV. Vernacular Architecture: ICOMOS International Committee on Vernacular Architecture. In Proceedings of the 10th General Assembly, Battaramulla, Sri Lanka, 30 July–4 August 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Belluschi, P. The Meaning of Regionalism in Architecture; Architectural Record: New York, NY, USA, 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Norberg-Schulz, C. Genius Loci: Towards a Phenomenology of Architecture; Rizzoli Publisher: New York NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- ICOMOS. International Charter for the Conservation and Restoration of Monuments and Sites (The Venice Charter). 1964. Available online: www.international.icomos.org/charters.htm (accessed on 7 April 2018).

- UNESCO and World Bank. Culture in City Reconstruction and Recovery; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2018; Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/30733 (accessed on 18 April 2021).

- Yildirim, E.; Baltà Portolés, J.; Pascual, J.; Perrino, M.; Llobet, M.; Wyber, S.; Phillips, P.; Gicquel, L.; Martínez, R.; Miller, S.; et al. Culture in the Implementation of the 2030 Agenda. 2019. Available online: https://www.ifla.org/files/assets/hq/topics/libraries-development/documents/culture2030goal.pdf (accessed on 18 April 2021).

- UNESCO. Culture 2030: Rural-Urban Development China at a Glance. 2019. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000368646 (accessed on 18 April 2021).

- Karakul, Ö. Folk Architecture in Historic Environments: Living Spaces for Intangible Cultural Heritage. Int. Q. J. Cult. Stud. 2007, 19, 151–163. [Google Scholar]

- Karakul, Ö. A Holistic Approach: Unity of Tangible and Intangible Values in the Conservation of Historic Built Environments. In Proceedings of the 11th World Conference of Historical Cities, Venue, Konya, 10–13 June 2008; pp. 43–57. [Google Scholar]

- Rapoport, A. House, Form and Culture. Prentice-Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Rudofsky, B. Architecture without Architects: A Short Introduction to Non-Pedigreed Architecture; University of New Mexico Press: Albuquerque, NM, USA, 1987; ISBN 0-8263-1004-4. [Google Scholar]

- Fock, N. Et sted i skoven-en verden-et univers in Brasilien. Jordens Folk 1986, 21, 61–69. [Google Scholar]

- Griaule, M.; Dieterlen, G. The Dogon of the French Sudan (Mali) In African Worlds, Studies in the Cosmological Ideas and Social Values of African Peoples; Forde, C.D., Ed.; Oxford university Press: London, UK, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, P. Encyclopaedia of Vernacular Architecture of the World; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Levi-Strauss, C. The Way of the Masks; Univ. of Washington Press: Seattle, DC, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Stender, M. Towards an Architectural Anthropology—What Architects can learn from Anthropology and vice versa. Archit. Theory Rev. 2017, 21, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durckheim. Les formes Elementaires de la Vie Religieuse; Felix Alcan Paris: Metz, France, 1925. [Google Scholar]

- Rassers, W.; Panjii, H. The Culture Hero: A Structural Study of Religion in Java; Martinus Nijhoff: The Hague, The Netherlands, 1940. [Google Scholar]

- Schefold, R. Anthropology. In Encyclopedia of Vernacular Architecture of the World; Oliver, P., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1997; Volume 1, pp. 6–8. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, L.H. Houses and House-Life of American Aborigines; Univ. of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1881. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. The Logic of Practice; Nice, R., Ed.; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Rapoport, A. The Meaning of Built Environment: A Non-Verbal Communication Approach; University of Arizona Press: Tucson, AZ, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Gluckman, M. Ethnographic data in British social anthropology. Sociol. Rev. 1961, 9, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Velsen, J. The Politics of Kinship: A Study in Social Manipulation among the Lakeside Tonga; Manchester University Press: Manchester, UK, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Barnard, A.; Spencer, J. (Eds.) Encyclopedia of Social and Cultural Anthropology; Routledge: London, UK, 2000; p. 180. [Google Scholar]

- Renn, O. White article on risk governance: Toward an integrative framework. In Global Risk Governance; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2008; pp. 3–73. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, C.M.; McArthur, S. Integrated Heritage Management; Stationary Office: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Bakri, A.F.; Ibrahim, N.; Ahmad, S.S.; Zaman, N.Q. Valuing Built Cultural Heritage in a Malaysian Urban Context. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 170, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Seamon, D. Phenomenology and vernacular lifeworlds. Trumpeter 1991, 8, 201–206. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape (HUL); UNESCO World Heritage Centre: Paris, France, 2011; Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/uploads/activities/documents/activity-638-98.pdf (accessed on 19 April 2021).

- UNESCO. The HUL Guidebook. Managing Heritage in Dynamic and Constantly Changing Urban Environments. A Practical Guide to UNESCO’s Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape. UNESCO, 2016. Available online: http://historicurbanlandscape.com/themes/196/userfiles/download/2016/6/7/wirey5prpznidqx.pdf (accessed on 25 April 2021).

| Aim | To Propose a Value Assessment Framework as Guidance for Assessing the Ranges of Values in Vernacular Architecture for Value-Based Conservation. | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Aspects | Objectives | Undertakings | Method |

| 1. Background and the State-of-the-art | (1). To define value typologies in the context of heritage value assessment. (2). To determine the knowledge gap as regards the challenges associated with value typologies in the value assessment process. | (1). Examine relevant literature (books, journals, articles, libraries and databases, etc.) to define value, value typology and its limitations in the context of vernacular architecture. | LTR |

| 2. Conceptual Framing | (1). Examine the conceptualization of vernacular architecture as contextualized heritage which rejects universal value typologies. (2). Develop criteria and categories for the value characterization of vernacular architecture. (3). To describe the criteria and their relations to as to determine the approach to the assessment of each category. | (1). Search for appropriate author and theory for conceptualizing vernacular architecture as contextualized heritage (2). Examine relevant theory for theorizing the relationships between cultural practice, traditional process and form creation. (3). Search the literature to develop a set of indicators and different categories of value characterization | LTR/CA |

| 3. Development of the VVM | (1). To develop a framework that demonstrates the relationship between cultural practices, traditional processes in the creation of vernacular form are the intangible and tangible values in vernacular architecture. (2). To suggest the approach for assessing the valuing the characterization of vernacular values (3). Suggest the participation approach for each value characterization. (4). To develop the Vernacular Value Model by integrating all the suggested fragments | (1). Search for appropriate documents to buttress the assumptions concerning the fragments of the framework. (2). Search for an appropriate epistemological approach to assessing the assumptions about the value. (3). Search the criteria for selection of participants for each level of value assumptions. (4). Draft the vernacular value model which incorporates all the fragment parts. | CA/DA |

| 4. Conclusion | Discuss the implication of results and suggest the recommendations on its empirical application for a participatory conservation approach for vernacular architecture. | ||

| Author/Year | Proposed Value Typologies | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Riegl, 1901 | Age; Historical; Commemorative; Use; Newness | |||||

| Lipe, 1984 | Economic; Aesthetic; Associative/Symbolic; Informational | |||||

| Carver, 1996 | Market Value | Community Value | Human Value | |||

| Capital/Estate; Production; Commercial; Residential | Amenity; Political; Minority/Disadvantaged/Descendant; Local Style | Environmental; Archeological | ||||

| Frey, 1997 | Monetary; Option; Existence; Bequest; Prestige; Educational values | |||||

| Ashley, 1998 | Economic; Informational; Cultural; Emotional; Existence values | |||||

| Throsby, 2001 | Aesthetic; Spiritual; Social; Historical; Symbolic; Authenticity values | |||||

| Mason, 2002 | Economic | Sociocultural | ||||

| use values. | historical | |||||

| non-use values: | cultural/symbolic | |||||

| existence | social | |||||

| option | spiritual/religious | |||||

| bequest | aesthetic | |||||

| Feilden, 2003 | Emotional Value | Cultural Value | Use Value | |||

| Wonder; Identity; Community; Spiritual and Symbolic values | Documentary; Historic; Archeological; Age and Scarcity; Aesthetic and Symbolic; Architectural; Townscape, Landscape and Ecological; Technological and Scientific | Functional; Economic; Social; Educational; Political and Ethnic | ||||

| Keene, 2005 | Social; Aesthetic; Spiritual; Historical; Symbolic and Authenticity values | |||||

| Appelbaum, 2007 | Art; Aesthetic; Historical; Use; Research; Age; Educational; Historic; Newness; Sentimental; Monetary; Associative; Commemorative; and Rarity | |||||

| Orbaşlı, (2008) | Age and Rarity; Architectural; Artistic; Associative; Cultural; Economic; Educational; Emotional; Historic; Landscape; Local distinctiveness; Political; Public; Religious and Spiritual; Knowledge; Social; Symbolic; Technical; Townscape | |||||

| Stubbs, 2009 | Universal; Associative; Curiosity; Artistic; Exemplary; Intangible; Use | |||||

| Gomez Robies, 2010 | Typological; Structural; Constructional; Functional; Aesthetic; Architectural; Historical; Symbolic | |||||

| Szmelter, (2010) | Cultural | Contemporary/Socio-Economic | ||||

| Identity; Emotive; Artistic/Technical, Evidence; Rarity; Administrative | Economic; Resources; Functional; Usefulness; Educational; Tourism; Social; Awareness; Political; Regime | |||||

| Lertcharnrit, (2010) | Informational; Educational; Symbolic; Economic; Entertaining/Recreational | |||||

| Yung and Chan, (2012) | Economical | Socio and Cultural | Environmental and Physical | Political | ||

| economic viability | sense of place and | environmental | community | |||

| job creation tourism cost efficiency compliance with statutory regulations | identity continuity of social life social cohesion and inclusiveness | performance retain historical setting and patterns infrastructure townscape | participation supportive policies transparency and accountability | |||

| Gielen, et al., (2014) | economic | cognitive | health | experience | ||

| Author | Criticism of Value Typologies |

|---|---|

| Rudolff [15], (p. 60, 149) | “[…] presented typologies might help people articulate some value concepts—those clearly fitting into the respective categories—but at the same time aggravate reluctances to articulate values not fitting into the scheme. This means that heritage professionals, entering a participatory value assessment process with a set of value typologies have already pre-selected the value types they expect to hear” |

| Leif Harald Fredheim & Manal Khalaf, [3], (p. 465) | “Value typologies are often designed and implemented without understanding the implicit consequences of the inclusion and omission of values […] and thus resulting in decisions being based on implicit, rather than explicit, value assessments in practice”. |

| Avrami et al. [38], (p. 8) | “Though the typologies of different scholars and disciplines vary, they each represent a reductionist approach to examining very complex issues of cultural significance”. |

| Mason [5], (p. 10) | “Typologies implicitly minimize some kinds of value, elevate others, or foreground conflicts between the cultivation of certain values at the expense of others”. This is in coherence with the observation of Rudolff ([12], p. 60, 147) who argued that […] heritage professionals, entering a participatory value assessment process with a set of value typologies have already pre-selected the value types they expect to hear” |

| Stephenson, [56], (p. 128, 137–138) | “It is apparent that the application of assessment typologies may also fail to reflect the nature and range of values expressed by those who feel they ‘belong’ to the landscape […] Traditional landscape assessment methods which focus on discipline-specific value typologies may fall short of revealing the richness and diversity of cultural values in landscapes heldby insiders”. |

| Nara Document on Authenticity, [59], (p. 9, 11) | “[…] All judgements about values attributed to heritage […] may differ from culture to culture and even within the same culture. It is therefore not possible to base judgements of value […] on fixed criteria.” (Cited in [15], p. 57). |

| Stephenson [56], (p. 129) and Emerick [60], (p. 225) | They also suggested that value typology has the tendency to be driven by non-Aboriginal global society and national values in contrast to local and regional Aboriginal values that are not ‘authorized’ may be delegitimized. Thus, the operationalized ‘authorization’ of value operationalizes implicit professional preference and may cause the impoverishing of heritage [60], (p. 225), [61], (p. 36), [62] |

| Affelt, [6], (p. 10) | “the valuation itself will bear the mark of such expert, depending on the methodology used, personality traits stemming from the expert’s knowledge and experience in evaluation procedures, his aesthetic sensitivity, the ability of lateral thinking and emotional attitude towards the object of research” [6], (p. 10) “rather than integrating the values of people” [6] cited in [63], (p. 756). |

| Dimensions | Guiding Contexts | Characterization and Indicators | Value Characterization |

|---|---|---|---|

| Static Dimension | Form | The tangible, measurable aspect of vernacular architecture otherwise known as a material symbol (cosmological or esoteric anthropomorphic) or objectification of process and practice of a people (Bellushi, 1955; Rapoport, 1969; Rudofsky, 1965; Niels Fock, 1986; Griaule and Dieterlen, 1954; ICOMOS, 1999; Oliver, 1997) | Tangible and Intangible value |

| Dynamic Dimension | Process | The concept of ‘process’ provides a means by which we can begin to explore a typologically ambiguous and hybrid-built environment. The human-nonhuman relationship, the man- landscape dialogue which informs the creation of the vernacular architecture (Rapoport, 1969; Levi-strauss, 1982; Stender, 2017; ICOMOS, 1999) | Intangible value |

| Practice | The person-to-person tradition informed relationship drawing on a common cultural and heritage capital to construct a vernacular building (Durckheim, 1925; Rassers, 1940; Schefold, 1997; Griaule and Dieterlen, 1954; Morgan, 1965; Karakul, 2007) | Intangible value |

| Concept | Epistemology/Analytical Model | Operationalization |

|---|---|---|

| Form | Etic | Disciplinary experts: Outsider |

| Process | Emic | Community and stakeholder: Insider |

| Practice | Emic + etic | Disciplinary experts, community and stakeholders: Insider and Outsider |

| Value Characterization | Assumptions on Characterization | Conceptual Indicator | Epistemological Approach | Operationalization: Level of Participation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simple | Based on material evidence of the vernacular form | Form | Positivist/technical/expert interpretive | Disciplinary experts |

| Complex | Based on synergistic values which are not evident or striking. There are tendencies for stochastic effects (variation of perceptions) due to the different understanding of the synergies between the tangible and the intangible | Form/Process | Normative/radical empiricism | Community and stakeholder |

| Uncertain | These are transitional/ generation dependent intrinsic values. These are unspoken/temporal/abstract values based on the congruence of the form, the process and the practice in a particular setting. | Form/Process/practice | Normative/radical empiricism and positivist paradigm. | Disciplinary experts, community and stakeholders |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Olukoya, O.A.P. Framing the Values of Vernacular Architecture for a Value-Based Conservation: A Conceptual Framework. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4974. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13094974

Olukoya OAP. Framing the Values of Vernacular Architecture for a Value-Based Conservation: A Conceptual Framework. Sustainability. 2021; 13(9):4974. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13094974

Chicago/Turabian StyleOlukoya, Obafemi A. P. 2021. "Framing the Values of Vernacular Architecture for a Value-Based Conservation: A Conceptual Framework" Sustainability 13, no. 9: 4974. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13094974