Abstract

Tourism as a tool for the enhancement and conservation of heritage represents an opportunity for many managers of cultural properties. However, despite the numerous works developed so far on tourism governance, the elaboration of preliminary studies for decision-making in heritage buildings is still a challenge. Considering the ecosystem services approach, an index is proposed which allows tourism and cultural heritage managers to analyze and quantify the level of tourist exploitation (use) of a monument for the services (benefits) that it offers to society. In this paper, a multi-criteria evaluation system was proposed, related to the main use of the building and its relationship with various tourism components, which have been classified as cultural, leisure, recreational, lodging, catering, intermediation, transportation, and event organization. The model has been applied to the Parroquia del Mar (Alicante, Spain) of great cultural relevance, but not exploited for tourism. The results obtained demonstrate the usefulness and validity of the model, considered as a tool capable of bridging the gap between heritage conservation and its touristic use, highlighting the importance of the services offered as necessary attributes for its (re)valuation, combining the social benefits of its exploitation, its touristic use and the awareness of its conservation and protection.

1. Introduction

When we refer to heritage, we reason that, just as there is an individual heritage, there is also a collective heritage. The concept of heritage—cultural, historical, and natural—is a human construction and, as such, is subject to change depending on the historical and social context. Currently, it is presupposed a heritage of all humanity, including cultural assets and nature, being part of a version of collective heritage created by modern society. In this way, the existence of an indisputable common heritage of a cultural character is universally recognized, assets coming from a legacy of civilizations, which all human beings deserve equally.

According to this premise, cultural heritage is a useful asset to societies and serves different purposes. Therefore, if the right of the receiving generation is to enjoy its values, the duty it acquires is to pass it on to future generations in the best possible conditions [1].

International organizations such as the International Centre for Study of the Preservation and Restoration of Cultural Property (ICCROM) recognize the importance of cultural heritage conservation, not only from the perspective of tangible heritage, but also in the area of safeguarding and raising awareness of heritage as a means to improve people’s lives [2]. This approach, linked to tourism activity as a means to bring cultural heritage closer to society, implies a new way of understanding and interpreting heritage, i.e., a paradigm shift that goes beyond the search for conservationism or maximum profitability of cultural assets, but aims to create a bridge between the two, providing, in turn, an integrative perspective where society, tourism, heritage and sustainability go in unison.

Several authors mention tourism potential as a starting point for assessing the possibilities for the enhancement and use of cultural assets and the territory for tourism and social development. Zimmer and Grassmann [3], Blanco [4], and Calderón–Puerta et al. [5] define the tourism potential as the evaluation of supply, demand, competition, market trends, and the characteristics or “vocation” of a territory for tourism activity. They also refer to the capacity of regional or municipal tourism products to satisfy the current interests and preferences of visitors. López [6] and Reyes et al. [7] define it as a way of evaluating, through hierarchical processes, those factors that affect a destination, such as facilities, accessibility, available tourism resources, or connectivity. In contrast to Cary [8], who argues that the potential of a tourism resource will be given by its inherent value as a tourism resource, in a fortuitous way, without the need for facilities or specific infrastructures to enhance it.

In the case of cultural assets, knowing the potential and capacity of a cultural resource to be used for tourism can be an opportunity for its rehabilitation, conservation, and maintenance [9], energizing and expanding the economic activities of the place where it is located and providing possibilities for development beyond the main use of the object.

Currently, there are numerous methodologies to analyze the tourism potential of destinations [10,11,12] from multiple approaches, such as through the analysis of the presence of destinations in social networks [13]; with the application of the Delphi technique from interviews with experts [14]; the SWOT method to know the main weaknesses and strengths [15]; or even complex mathematical methods [16,17]. However, the existing literature on the tourism potential of specific cultural assets focuses mainly on aspects related to its value as a heritage asset from the historical, architectural, and artistic perspective [18,19,20,21], or even from the vision of social actors [22]. This makes necessary, therefore, a new approach that contemplates the quantification of services and their typology from the perspective of human welfare and to what extent these can be managed to increase the tourist and cultural potential of the building, including the geographical, physical-natural, social, and cultural scope.

It is necessary to develop transferable, applicable, and operational methodologies [23], which streamline the management processes and make visible the importance of the conservation of assets for the welfare of the population through the services they provide to society. This is explained by Leiper [24] in his study on the tourist system and the importance of services to make the tourist machinery of destinations work from the geographic dimension, a tool that, beyond the academic field, can be used by heritage managers and technicians.

Likewise, the sanitary situation resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the importance of knowing the capacity of cultural assets to (re)adapt their uses and services to possible new needs and demands of society. Now more than ever, there is a need to recognize and incorporate support functions for cultural heritage management in response to the crisis and planning for the recovery.

This article aims to fill this gap, proposing a management tool for the enhancement of heritage from the perspective of use value, the utilization of the property, and its capabilities to generate benefits to society according to the services it provides (both tangible and intangible), which is replicable to other built cultural assets, quantifiable, and easily interpretable.

The study considers the different approaches to heritage conservation, intervention, and tourism management of cultural properties. Subsequently, the theories developed in research on the tourism potential and experience related to cultural properties were analyzed, starting previously with an analysis of existing cultural heritage management tools and followed by an analysis of the ecosystem services approach, applied so far to natural heritage. Next, the proposed model is presented, followed by its application to the case study of the Parroquia del Mar in Jávea (Alicante, Spain) and a discussion of its possible applications, limitations, and merits. It concludes with an analysis of how the proposed approach can be employed in other cultural assets for the development of their tourism activity from a sustainable, inclusive, and responsible perspective.

2. Background: From Conservationism to Implementation

Given that tourism is sometimes a threat that tends to damage heritage assets [25], some of the approaches developed for the conservation and valuation of cultural properties should be considered, in order to develop methods to convert them, as mentioned by Choay [20], into an economic product without undermining their conservation. To this end, according to the author, there are several stages ranging from conservation and restoration to (re)use, including staging and animation.

2.1. Approaches to Heritage Intervention and Its (Re)use

Between heritage and its conservation and restoration there has been a reciprocal instrumentalization [26], on which its correct valuation depends [20]. Resulting from the conservative and restorative thinking developed during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, debates on the notion of heritage have revolved around the concepts of authenticity, identity, management and recipient, accompanied by fundamental aspects of conservation, restoration, rehabilitation, and maintenance [27].

We began with some theses such as by John Ruskin (1819–1900), the main defender of the “golden patina of time” [28], followed by others such as by Cesare Brandi (1906–1988), where the work of art is perceived as a common product, with a particular use or function and whose restoration is necessary to provide useful functions to heritage assets [29]. Camilo Boito (1836–1914) advocated a restrictive intervention and whose concept of restoration is embodied in the idea of consolidating rather than repairing and repairing rather than restoring, but in the case of a necessary restoration, it is essential to give absolute visibility to any modern intervention [30]. This approach is appreciated in several examples around the world, from the temple of Teotihuacan in Mexico to the Castle of Pombal in Portugal.

It follows, therefore, that the predominant approach to intervention, protection, and enhancement of heritage is often associated with terms such as identity, authenticity, history, or tradition, delimiting a space where its use makes sense. The tendency of texts dedicated to heritage management is usually approached from a conservationist perspective or strategy [30] and with a respective professional horizon mainly dedicated to experts of the past: restorers, archaeologists, or historians. However, the study of heritage is beginning to be linked to other conceptual frameworks, such as tourism, geography, communication, or marketing. As described by García [31], some concepts associated with the commodification of heritage are often considered as the main adversaries of heritage, as they represent a series of external challenges and threats coming from different universes.

An uncontrolled number of visitors, overexploitation, or inappropriate uses can generate a degradation of cultural properties, sometimes with no return. In the same way, the lack of tourist interest in cultural properties can cause serious problems arising from non-use [32]. This fact, sometimes observed in certain abandoned historic buildings, may pose a threat by not obtaining profitability from their conservation and maintenance [33].

2.2. The Staging of Heritage: The Monument as Spectacle

Several authors share ideas about heritage assets as a spectacle worthy of being admired in the most flattering way possible. Viollet–LeDuc [34] and Camillo Sitte [35] already agreed on this idea, seeing the monument as a main element of urban art and, with it, a way of giving it prominence as if it were a divinity. With the idea of conceiving the monument as a spectacle, it often runs the risk of its possible trivialization, loss of authenticity or reconversion from a property to a simulacrum of reality as mentioned by Baudrillard and Proto [36]. On the other side, tourism as an instrument for the dissemination, education, and interpretation of heritage can be a turning point for many heritage assets at risk of disappearing, by promoting their valuation, maintenance, and social awareness [37]. Such actions are often carried out through various interpretative means, such as equipment (electronic light and/or sound systems), intermediaries (actors or interpretive guides), or information tools (signage). However, this type of equipment is sometimes not available in certain heritage assets, which makes interpretation and learning difficult [38]. This is more common in buildings with a specific function or use, such as sports centers, conference centers, or offices.

From this premise, it follows that depending on the available infrastructures and the use and services that a building offers to society, it will be possible to estimate to what extent alternative services can be offered to increase tourist interest in the place and, in turn, provide a direct benefit to society. In the same way, as mentioned by Garau [39], the attractiveness of a place does not necessarily depend on its great cultural value, but it is determined by the way in which it is inserted in the interpretative process, understood as an active process where knowledge passes to valorization through the preservation and restoration of the property, exerting a positive impact on the cultural and economic development of the territory [39].

Likewise, given the nature of cultural assets, there will always be an intrinsic cultural value in what is being analyzed. This means that, in addition to the specific function of a given building, it will have, in turn, a cultural function that benefits society (because of its history, its architectural, aesthetic, artistic value) that justifies its patrimonialization. It will therefore have a series of elements, processes and attributes (tangible or intangible) to which a range of cultural services can be associated [40]. As mentioned by Ballart and Juan i Tresserras [1], the value of cultural heritage will be determined by the use of the assets (use value), by the attraction it awakens in the senses (formal value) and by its link with the culture or cultures of the community (symbolic value).

Considering that cultural assets are the essence of tourism in a multitude of destinations [41], knowing to what extent these assets can offer an alternation of services focused on improving tourism activity represents an opportunity for their enhancement and for recovering certain historical constructions that are in a state of abandonment [42]. “To increase the tourist attraction, it is important to develop specific products by exploiting the advantages provided by local cultural resources, local socio-economic infrastructure, tourism infrastructure provision and services development” [43]. For this reason, special attention should be paid to the opportunity offered by what has been developed in the framework of ecosystem services for the enhancement of natural heritage, with emphasis on cultural services.

2.3. The Social Dimension of Cultural Heritage

In the 21st century, the built cultural heritage faces the challenge of its restoration and re-adaptation as a tourist resource. The interweaving of historical, economic, cultural, and symbolic factors makes them perfect supports for new cultural and recreational functions. This is why, in many historic centers or old city centers, residential, religious, tourist, administrative, commercial, or cultural functions coexist in permanent tension. The full recovery of cultural heritage necessarily implies assigning to it functions that, in many cases, are related to tourism, leisure, and culture [44].

In view of the above, there is, therefore, an obligation to approach cultural heritage as a strategic ally, whose vision implies inserting it fully into the urban life of its territory. This approach, by integrating economic and cultural dimensions, presents opportunities for society, but also challenges, so that sustainability as a reference is a necessity and a guarantee for the future by promoting the conservation of the assets themselves and allowing the integration of tourism in a framework of compatibility with society, as well as with the economy and, fundamentally, with the cultural heritage [45].

Tourism is a cross-cutting activity that offers important opportunities for the integrated recovery of architectural and urban heritage. Its insertion into the life of historic cities is one of the great challenges, which is why it is necessary to consider in an interrelated way the human, physical, and environmental spheres, as advocated by the European Union in the elaboration of the 2030 Agenda [46].

A correct knowledge of the impact of the tourist use of cultural assets should serve to determine their influence on society and thus develop multifunctional strategies that contribute to the recovery of cultural heritage and the achievement of new functional balances.

However, it is important to be aware that cultural heritage is only a resource that can be “exploited” for tourism when it is properly conditioned, managed, and marketed. Therefore, the existence of a substantial cultural heritage does not always guarantee that it can become a potential destination for cultural tourism and its social exploitation.

Likewise, as mentioned by Parga–Dans and Alonso González [47], there is no point in patrimonializing cultural assets and turning them into tourism products, if the interests and motivations of the public are not considered for the conservation and sustainable (tourism) management of the assets.

The published Special Eurobarometer on Cultural Heritage [48] reveals the relevance of cultural assets for the European economy and society, where the results show that 80% of the more than 27,000 interviews conducted reflect a strong interest in cultural heritage as an important element for them, as well as its importance as an economic engine, triggering induced effects in the territory, such as the employment creation or the development of the tertiary sector.

On the other side, the Council of Europe framework Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society in 2005 [49] emphasizes and recognizes the need to include social values “as the centre of an enlarged and cross-disciplinary concept of cultural heritage”, and also proclaims the importance of highlighting the value and potential of the cultural assets used as resources for the sustainable development of the territory and the promotion of the quality of life of society. In light of the above, the importance of including the social dimension in projects for the enhancement of cultural assets is revealed, but also the value of the assets themselves as elements that generate economic development and quality of life.

It is essential, therefore, to explore the relationships between heritage and its value, tourism, and the perceptions of the local community, as hosts of the destination and as drivers of active participation in the development of cultural tourism in their territory [50].

2.4. Towards a New Approach to Heritage Tourism Management: Anthropic Services as Generators of Well-Being

Heritage consciousness is considered an ancient phenomenon, a generator of preservationist strategies [1]. As a starting point, heritage consciousness is based on the need to consider the uses of heritage as tools for its conservation, moving away from the idea of conservation for conservation’s sake, where the correlation between adaptive re-use and sustainability of cultural heritage is possible, by analyzing the invisible social context that influences the establishment of adaptive reuse strategies [51]. Heritage management—whose main objective is to achieve an optimal conservation of particularly appreciated assets, produced by human activity and that have lasted until the present, through an adequate use adapted to the requirements and needs of contemporary society, without undermining their preservation—has been in charge of all this.

The concept of “well-being”, although mainly linked to health, also implies a series of human needs, which are indispensable requirements for human development in all its magnitude. The definition of well-being proposed by the United Nations Millennium Ecosystem Assessment Programme [52] is as follows:

“Human wellbeing has multiple components, including basic material for a good life, freedom of choice and action, health, good social relations and safety. Welfare is at the opposite end of the spectrum from poverty, which has been defined as ‘pronounced welfare deprivation’. The components of well-being, according to people’s experience and perception, depend on the situation, reflecting local geography, culture and ecological circumstances.”

The ecosystem services approach is broadly applied to evaluate the importance of territories in terms of the services provided to society, as shown by the study conducted by Scorza et al., which measures the specialization and tourist attractiveness of the territory based on ecosystem services [53].

According to this study and applied to heritage, this approach requires decision-making processes that are in line with the needs of individuals and their communities. This paradigm shift, therefore, emphasizes the need for the creation of models focused on people and their needs, addressing, in turn, the needs of the tourism system [24] and the conservation of cultural heritage.

On the other side, the ecosystem approach, originally used for natural environments, emphasizes how and to what extent biodiversity benefits human wellbeing [54,55,56]. This approach helps to improve the valuation of natural systems by society and to make decisions without undermining the conservation of the system as a whole. With this orientation, and considering its application in cultural heritage, the system used will not be a natural environment but a building or sculpture (socio-system), as proposed by Arcila-Garrido et al. [56], where they introduce the concept of ecosystem services as a tool for decision-making and tourism valuation of cultural heritage through the services and benefits they provide to society.

Considering the importance of services, as the main source of experience in tourist activity [57], developing an approach that allows the level of tourist potential to be measured beyond its historical and/or aesthetic value, but also based on the building’s current services, could represent a new proactive and complementary perspective to establish the basis on which to act.

In view of the above, this article proposes the incorporation of a management tool that analyzes the tourism value of cultural assets for the services they provide or are capable of providing and, on the other hand, to validate the tool with a specific case study: Parroquia del Mar.

2.5. A Controversial Religious Heritage: The Case of the Parroquia del Mar

The geometric avant-garde approach, combined with concrete as the primary constructive material, emerges as the main expression of 20th century architecture, being part of a single architectural message beyond its aesthetics [56]. However, within the Modern Movement, a current emerged, commonly referred to as “Brutalism” (derived from the French “béton brut” or “raw concrete”), which never had the full approval by a large number of architects [58]. Both the name and its crude and dehumanized appearance have generated constant attacks or total abandonment of the buildings, which have ended up, sometimes, destroyed [51,59].

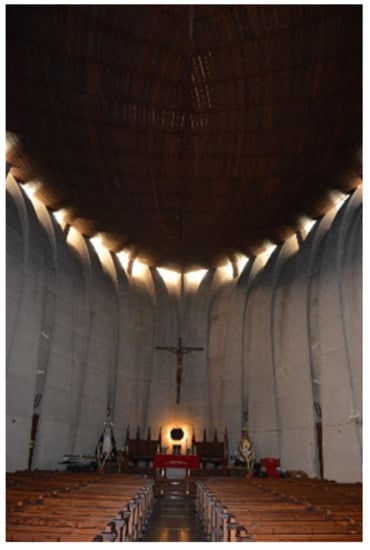

During the “tourist boom” in Spain in the 1960s, the project of the Church of Our Lady of Loreto, more commonly known as Parroquia del Mar (Parish of the Sea), was undertaken in the city of Jávea (Alicante), replacing an old hermitage dedicated to fishermen (Figure 1). The building is directly linked to “Brutalism”, with a strong direct connection to concrete as an identifying element. Carried out by Fernando García–Ordoñez and Juan Mª Dexeus Beaty, they opted for an ovoid floor plan, a design without corners, in which the zenithal lighting had a special role, achieving an ethereal atmosphere (Figure 2 and Figure 3). This temple “is visualized as if it were the bottom of the sea, whose surface is furrowed by the boat of salvation creating waves of foam that turns into white light” [60].

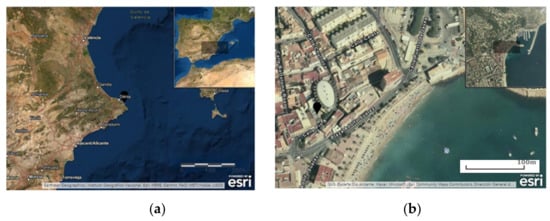

Figure 1.

Location and view of Parroquia del Mar. Aerial photograph of the study field location. (Jávea, Alicante) (a); Aerial photograph of the Parroquia del Mar building (b). Source: Own elaboration.

Figure 2.

Side view of the Parroquia del Mar. Source: Photo by the authors.

Figure 3.

Interior view of the central nave of the Parroquia del Mar. Source: Photo by the authors.

The use of the new religious images presented in the building is in line with the renovation advocated after World War II by the Catholic Church, which proposed the rapprochement of ecclesiastical art to the sensibility of 20th century modern art. The architectural modernity is manifested with its own artistic style, a “Brutalism” of forms and finishes directly related to its symbolism: The celestial vault has been replaced by the surface of the sea, making the whole almost a secret hidden in the tourist real estate maelstrom.

Despite its cultural, aesthetic, and architectural importance, the building has not been valued beyond its religious function, which could be due to the low social appreciation of this building typology [25]. On the other hand, the possibility of expanding the offer of complementary services to visitors (residents and tourists) is not currently being contemplated. One of the main reasons of its non-existent of tourism offerings is the lack of cultural and recreational orientation in the management of the building that allows, firstly, the improvement of its enhancement in order to make society aware of its cultural importance, and, secondly, to make its use and enjoyment profitable, contributing, in turn, to the availability of resources that allow its maintenance. For this reason, applying the proposed model to this building can be an opportunity to facilitate decision-making towards an improvement of its cultural appreciation, application of possible complementary services, and improvement of its conservation.

The analysis, therefore, consists of determining the importance that the incorporation of certain services in the cultural assets may have for their maximum tourist use, from the point of view of conservation, awareness, and tourist sustainability. This will facilitate decision-making regarding the development of potential complementary activities and the improvement of their enhancement and marketing.

3. Materials and Methods

The present study involved different research conducted on the evaluation of cultural heritage. For the design of the evaluation model proposal, the theoretical approach developed by Arcila–Garrido et al. [56] on the adaptation of the ecosystem services evaluation system applied to built cultural heritage was taken as a reference. In summary, a combination of methodologies was carried out, structured as follows:

- First, it was necessary to review the literature on published studies related to the theory of ecosystem services, tourism potential, and enhancement of cultural heritage, and monographs and papers related to the uses and interventions of heritage, tourism experience, cultural tourism, and heritage management;

- For the approach to the main services offered, the categories used by Haines and Potschin for CICES (Common International Classification of Ecosystem Services) [61] and from TEEB (The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity) [62] were taken as a reference;

- Inspired by Leiper’s tourism system model [24], we selected those factors associated with tourism resources that make possible the transformation of a heritage site into a marketable tourist attraction. These factors served as a starting point for the selection of the evaluation criteria of the proposed model;

- To evaluate the components, a reference framework was established, whose values are given after the evaluation, when considering the maximum number of service supplying units (SUs) that a property may have;

- To validate the proposed model, it was applied to the Parroquia del Mar. To this end, a field visit and an interview with the parish staff were conducted to determine the level of tourism use, the current state of conservation and use, and the possibilities for tourism development;

- The interview was conducted in the building with the parish secretary and was structured as follows: (1) characteristics of the building and current state of conservation; (2) main uses and complementary uses; (3) occupied and available spaces (unused); (4) types of events scheduled; (5) main visitors and influx of visitors throughout the year (before the pandemic by COVID-19); (6) communication channels used; (7) perceived social perception about the building and importance for the city as a symbol. The interview was conducted on-site in April 2021.

During the design and development of the model, we opted for an interpretation of cultural assets from a global, integrative, and ecosystemic paradigm, understanding the asset as a set of resources (units and components) that interact with each other, generating a common and enriched tourist experience among all the elements that make it up. The property is conceived as a socio-system in order to help the practical understanding of the tool, simplifying the tourist reality in the property and its structure and, on the other side, facilitating its interpretation. This perspective makes it possible to recognize the multiple connections between its elements and to break it down, in turn, into subsystems.

4. Tourism Potential Index for Heritage from the Ecosystem Services Approach (TPIH-ES)

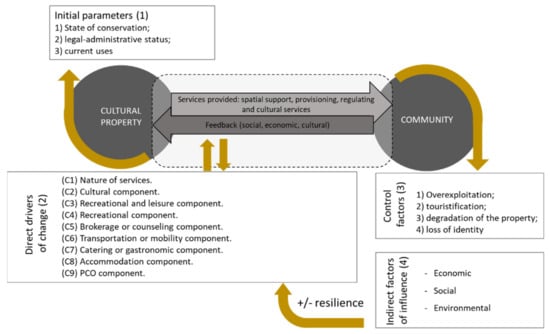

The process of applying the tourism potential index for heritage from the socio-ecosystemic perspective (TPIH-ES) was applied considering the system (Figure 4) that conformed the relationship between the cultural property and the community (visitors and residents).

Figure 4.

Socio-system of cultural properties and its components (tourism–society). Source: Own elaboration.

As shown in Figure 4, according to the initial parameters (1), services issuers are considered to be those facilities or supplying units (SUs) that constitute the property and that provide or can provide different types of services. These have an impact on the community (residents and visitors), which, in turn, generate a return (economic, social, and cultural) to the building and its elements, driven by the tourism components (2). The greater the impact on these components, considering the control factors (3), the greater will be, on the one side, the tourism potential of the property as a tourism product and, on the other, its resilience to possible changes or indirect influencing factors (4).

In order to create the link between well-being, tourism, and heritage, the concept of “anthropic services” was used, which are potentially capable of generating benefits to society and, in turn, are essential for other systems to do so. Considering the above, in order to know to what extent the system can be influenced, given the components, the following steps are proposed for the application of the TPIH-ES index: (1) selection and classification of the supplying units (SUs) by type of services offered and subcategories; (2) evaluation of the SUs from the tourism perspective; and (3) categorization of the TPIH-SE.

4.1. Selection and Classification of the Supplying Units (SUs)

For the first step in the application of the proposed model, we selected those generating facilities (SUs) of anthropic services that are part of the property and its structure. Understanding the building as a system, the SUs could be those facilities that configure the systemic area (e.g., cafeteria, store, parking, ticket offices, or gardens).

For the classification of these services, the categories used by CICES [61] were used as a reference, since the main human needs satisfied by the functions developed by the different anthropic structures could be classified into these categories. Likewise, the spatial support service was included, based on the study conducted by Arcila–Garrido et al. [56], associated with the space and physical support offered by certain structures. Therefore, the services were classified as follows:

- Spatial support services: The space and/or adapted physical support necessary to enable or sustain certain needs and functions (e.g., living, resting, storing, facilitating activities, and operations);

- Provisioning services: The provision of people, goods, and products necessary to cover needs or facilitate other services (e.g., provision of workers, basic urban services, transformed goods, economic income, information, and knowledge);

- Regulating services: Those that serve to adjust, regulate, mediate, or bring order to social processes, human functions and activities, or their basic functions (e.g., regulating the movement of people, social and economic interactions, security, physical and mental health);

- Cultural services: The characteristics and elements of human constructs that provide opportunities for people to obtain cultural benefits (e.g., visual, experiential, emotional, cognitive).

In order to make visible all the dimensions that society can value and, subsequently, to give qualitative and/or quantitative values to each of them, these four categories are classified into different subcategories (Table 1). This makes it possible to have a wide range in which to include all the possible services that can occur in cultural assets or in any other human construction. In addition, this system also makes it possible to interrelate sectoral interests in decision-making, which will facilitate the understanding of trade-offs in the event that the interest of one sector prevails over that of others.

Table 1.

Classification of anthropic services and examples of European buildings of cultural interest corresponding to each of them.

4.2. Assessment of the Supplying Units from a Tourism Perspective

In order to measure the potential attractiveness of the property according to the services provided, the direct relationship between the SUs that configure the property and its nature as a provider of tourism services (tourism experience components) is considered, understood as those complementary services necessary for the operation of the property as a tourism product.

For the selection of the criteria, the tourism system model proposed by Leiper [24] was taken into account, according to which tourism services (such as lodging, restaurants, transportation, or leisure) are indispensable for the proper functioning of the system.

The criteria selected for the TPIH-ES were classified in two groups that, in turn, offered a conceptual framework broad enough to incorporate other components that could appear: Firstly, the nature of the services (C1), if the SU is part of the main use of the property; and subsequently, the nature of the SU according to the tourism components (C2–C9):

- (C1) The character of the services (primary or secondary) according to the relevance of the function, considering the main use of the building;

- The nature of the supplying units, considering the following components;

- (C2) The cultural component, services that allow the appreciation, interpretation, and enjoyment of heritage (tangible or intangible/natural or anthropic);

- (C3) The recreational and leisure component, a set of activities and experiences that include shopping, enjoying entertainment activities, practicing sports, walking, and making use of cultural facilities;

- (C4) The ludic component, sports competitions, gaming services, or related to these activities;

- (C5) Intermediation or advisory services in tourism activities, including organization and marketing activities;

- (C6) Transportation or mobility, mobility services, or transfer of persons;

- (C7) Restoration or gastronomic component, services of food and/or beverages consumed on site;

- (C8) Accommodation, lodging services, or temporary residence for overnight stay.

- (C9) PCO (Professional Organization of Congresses and events) services of organization, development, and management of professional events.

Each of these criteria was used to evaluate the services offered by the supplying units. The greater the number of relationships between the different criteria, the greater the building’s capacity for tourism use.

4.3. TPIH-SE Categorization

The ratings given to each of the criteria depended on the case study, the functions it performed, and the available facilities. These ratings were determined on a scale of 0–1, within which three basic ranges were established to determine their potential (C—low, B—medium, A—high). The ranges were delimited according to the number of supplying units available, considering each one of them with its maximum and minimum possible score. Given the importance of cultural assets for tourism activity, greater weight was given to supplying units with a cultural component.

The operation of TPIH-ES can be summarized as follows:

where:

- S corresponds to each of the categories of services of each supplying unit;

- n corresponds to the number of criteria that fulfill the condition (direct relation with the service category);

- u corresponds to the assigned value of the supplying units *;

- * Those units that fulfill the cultural component criterion (C2) are given double the established general weight due to their importance as a tourist attraction. Where u = 0.22.

5. Results

Following the described process, the following steps were carried out for the application of the TPIH-ES to the case of the Parroquia del Mar: (1) identification of the systemic area and the service issuers; (2) classification of the main services and their categories; (3) selection of the tourism components associated with the services; and (4) assessment of the results obtained.

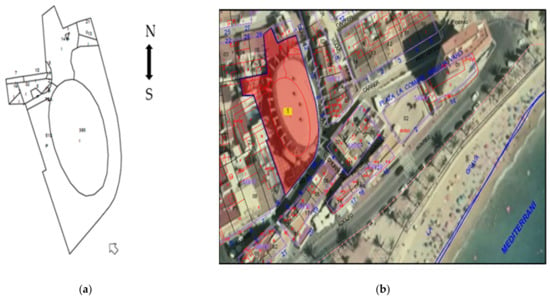

The territory where the socio-cultural activity is linked to the church occupies an area of 1.173 m2 according to the Official Headquarters of the Cadastre of Spain (Figure 5a). Due to the existing interrelation between the different supplying units of the building, the indicated area (Figure 5b) was considered the socio-system selected for the analysis.

Figure 5.

Cadastral polygon of Parroquia del Mar (a); Ortophoto of the Parroquia del Mar building. Parroquia del Mar socio-system (in red) (b). Source: Official Headquarters of the Cadastre of Spain.

Once the socio-system was established, the building’s SUs, services offered, and typology were considered and, subsequently, the relationship with the tourism components was assessed (Table 2).

Table 2.

Association of the tourism components to the supplying units (SUs) of the Parroquia del Mar.

Considering the types of services currently provided by the SUs, the results reflect that, within cultural services, the typology with the greatest potential to attract tourist flows are those dedicated to typology 4.3: “Spiritual, religious, symbolic, aesthetic, emblematic or ethical interactions”.

The SUs that provide such services are, in order of greatest to least potential, the central nave (0.5/1), as the main service of the socio-system, and the courtyard and choir (0.3/1), associated with tourism components related to culture, recreation, and leisure. In addition to cultural services, the church facilities also include certain SUs of special support services, with great potential for tourism: the auditorium and the classrooms (0.3/1), both belonging to typology 1.2: “Operational space for the development of human activities”, associated, in turn, with the tourism components related to culture and event organization. In terms of regulating services, only the parish office is worth mentioning as a possible SU of potentially tourist services. Its current use lacks value for tourism beyond intermediation (C5), and due to its activity does not currently contemplate a greater number of services. No provisioning services are currently being supplied.

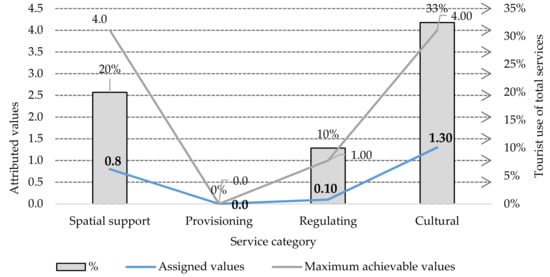

Regarding the general data by categories (Table 3), and considering the lower and higher limits of each range obtained (Table 4), the church is in the (C)/Low state of tourist exploitation, with a valuation of 2.2/6, where 22% of the SUs are potentially attractive for the promotion of tourist activity or have a direct relationship with the main services that influence tourist flows (Figure 6).

Table 3.

Results of TPIH-ES by categories for the Parroquia del Mar.

Table 4.

Achievable valuation ranges according to the SUs of the Parroquia del Mar.

Figure 6.

TPIH-ES results for the Parroquia del Mar.

These results provide, firstly, an approximate diagnosis of the current tourist use of the building and, secondly, an approximation of its tourist potential and capacity to attract visitors, based on the facilities currently available and the services offered. With this information, it is possible to begin the planning phase of future studies.

6. Discussion

The proposal tool (TPIH-ES) includes, as a novel element, a new approach to the management of cultural and heritage assets based on the analysis of the assets as socio-system, giving greater prominence to the elements that comprise them and the services they provide as the main differentiating element and enhancer of their functioning as a product. This approach aims to break down the existing barriers between heritage conservation and its social and tourist use from the perspective of services and technical equipment available.

The approach of the model indicates that the components related to the tourism experience have a fundamental role in the integrated evaluation of the whole. In contrast to Cary’s argument about the unintentional tourism experience [8], the tool reinforces the importance of complementary facilities (inherent to its marketing) as essential attributes to promote the property as a tourism product [39,40], which may, in turn, motivate feelings of identity and nostalgia through their management and marketing.

Additionally, the model makes it possible to determine the system’s capacity to absorb conflicts and recover from them through the transformation and adaptation of its modes of operation or the supply and adaptation of its tourism components, thus favouring its resilience and giving it greater decision-making capacity in the face of possible indirect influencing factors.

According to Ho and McKercher [23], it is more feasible to enhance the tourism value of cultural assets by acting on the services they provide to the community, as well as adapting their functions and activities according to the circumstances that may arise from external factors [23].

This tool also aims to highlight the importance of the social welfare generated by the conservation and enjoyment of heritage. The characteristics, as well as the environment and the particularities of cultural properties provoke a certain reaction in the users who visit them. This depends on the level of appreciation of the visitors or their capacity to appreciate the cultural properties, but it also depends on the benefits generated by the property through the services it offers, its capacity to generate emotions, and its link with the past, as mentioned by Ballart and Juan i Tresserras [1].

The TPIH-ES has been validated in the Parroquia del Mar (Alicante, Spain). In this sense, the building is positioned as one of the main architectural cultural resources of the 20th-century in the Spanish Levant. However, the actions carried out are oriented exclusively to the religious office, leaving aside recreational or leisure functions linked to cultural tourism. As mentioned by Laing et al. [42], although a heritage asset may have great cultural importance, its tourism potential may be limited if no actions are carried out for its commercialization or tourism exploitation [42].

The results indicate that, depending on the objectives set by the management of the building, measures to improve its tourist use should be focused on complementing cultural services, incorporating provisioning services and including tourist components related to leisure and recreation in the spatial support services, as well as incorporating specialized tourist intermediation services within the regulating services.

Likewise, the approach used can also influence urban management plans, since this type of services can be provided from the socio-system itself or from surrounding socio-systems, bearing in mind that systems are open and have permeable boundaries, so it is essential to analyze how they interact with their environment.

From this perspective, it can be concluded that the use of the TPIH-ES makes it possible to establish priorities in the management of the building in order to enhance its value or use for tourism. Knowing the current tourism potential of the building, measures can be introduced to improve its value and cultural appreciation, modifying the services offered or adapting its infrastructure with a view to expanding its tourism offer. The index, therefore, provides a response to the services that managers should improve in order to increase the building’s tourism potential.

Considering the above, recommendations to improve the experiential value in the Parroquia del Mar as a cultural asset include: (1) offering visitors attractive and accessible information about the architectural, historical, and cultural importance of the building; (2) installation of complementary material (signage) in the surroundings near the building; (3) design and offer specialized tourist guides in several languages, not only of the building, but also of its surroundings, in order to link the building with the surrounding landscape and to value its direct link with the sea; (4) value the building beyond its religious functions, but also as a cultural property; (5) complementing the official website with attractive cultural and recreational information for visitors; (6) expanding the use and functions of the classrooms and assembly hall as potential supplying units for cultural services; (7) offering local artisan products linked to the building (religious, cultural, and/or gastronomic products) to enable provisioning services and improve the profitability of the building; (8) organization of complementary activities in the central nave of the building (e.g., concerts and/or temporary exhibitions).

All of this, always based on an analysis of the possible interactions between the current and proposed services, is to ensure their compatibility and not to favor new services that may diminish the flow of services associated with the main function of the building.

In addition to having technical support about the capabilities and condition of the building, it is important to consider the current valuation status from the community (residents and tourists). The importance of social involvement has been highlighted by the Charter for the Conservation of Historic Towns and Urban Areas of 1987 [63], which states: “The participation and the involvement of the residents are essential for the success of the conservation program [sic] and should be encouraged. The conservation of historic towns and urban areas concerns their residents first of all” [63] Moreover, knowing the existing perception from society about heritage would allow important benefits to be obtained for the planning and management of tourism resources with a high cultural value [64].

However, the proposed model excludes the social dimension insofar as it does not consider the perception of the population in relation to the possible new uses that could be incorporated into the properties. Therefore, the results obtained through the model may not be interpreted in the same way by the local society and visitors, generating disagreements on the properties management and giving rise to controversies about possible uses or values [47].

For this reason, the model proposed in this study must be complemented with an analysis of the social values and needs of the community in order to carry out a tourism project or strategy for cultural properties, especially if they are in use [50].

Like ecosystem services, the valuation of anthropogenic services and their importance for the population is relative for each society and should be based largely on consultation processes. It should be kept in mind that the TPIH-ES model is an intermediate strategic tool, between legal protection, on the one hand, and conservation, restoration, and citizen participation, on the other.

Therefore, in addition to the results obtained from the application of the TPIH-ES, managers need additional information on technical aspects that may directly affect the property, as well as carrying out citizen participation processes in order to establish concrete and appropriate measures. Even if the managers determine that the building is in perfect conditions of maintenance and conservation, this does not imply that any action can be carried out with any intensity. Although it may be considered that providing tourist uses should be the main objective in heritage management, the mission, however, should move away from the reconversion of cultural properties into saleable tourist products to the detriment of their integrity, authenticity, and essence [20,33]. On the contrary, the mission should be to perpetuate the memory of the properties through means such as tourism, bringing culture closer to the community and promoting its conservation, protection, and maintenance.

7. Conclusions

This article reports the results of experiences, inquiries, and reflections on the enhancement, intervention, conservation, management, and study of cultural properties from a tourism perspective, in order to respond methodologically to the complexity involved in the systematic evaluation of the tourism potential of cultural properties, safeguarding their integrity, and promoting their adaptive (re)use and conservation. It is noted that this same concern has been explored in other academic studies, including theories of heritage restoration and intervention, which should be further explored.

The proposed management tool allows reinforcing the creation of tourist experiences in cultural or heritage assets, diagnosing the current state of their tourist potential, quantifying their tourist value in relation to services and making visible those problematic aspects to develop actions aimed at solving them. Although the present study is a support for future research, as well as to improve the enhancement of heritage in tourist environments, an in-depth analysis of the technical elements of heritage, as well as their intervention (if any), will be necessary for the managers who apply the tool.

According to the bibliographic review, many authors conclude that any cultural asset can become an object of desire with the right actions aimed at marketing it for tourism. Although certain leisure and recreation services constitute some of the fundamental aspects of tourist demand, the consumption of cultural goods must go beyond these concepts. If we are not able to disseminate or recognize cultural heritage as an identifying element of the territory, linked to the way of life of the community and its landscape, we run the risk of losing its meaning and value for society. The intervention of cultural heritage for its adaptation as a tourist resource must be approached from an integrative perspective, considering the territory as a dynamic social reality where tourism and culture offer opportunities for the functional recovery of the city. The functional problems should not be separated from the intervention of the property, if we are really committed to an integrated recovery.

The dynamic nature of human realities and the changes in the urbanistic conjunctures raise the need to establish closer connections between the policies of recovery of historic areas and the new uses, in short, to connect more closely the urban, architectural, economic, cultural, and social dimensions.

The complexity of modernist buildings, whose aesthetics may be unappealing to the non-specialist public, poses additional challenges, as they are unlikely to form part of mainstream tourism experiences in the destinations in which they are located unless there is significant development of the property’s setting.

In this sense, tourism as a means to promote culture and knowledge to society represents an opportunity to improve knowledge about 20th-century heritage. Likewise, the (re)utilization of the property for a new tourist activity allows not only to improve its awareness, protection, and conservation, but also the preservation of its cultural, historical, and architectural significance, as well as the retention and enhancement of its symbolic values and the adaptation to a new economically profitable alternative. The re-adaptation and re-utilization of cultural assets provides opportunities for tourism, but we must be aware of the fragility of heritage and the need for local control and management of resources. Local administrations, therefore, must take a leading role and commit themselves to the management of sustainable strategies for cultural heritage.

The main usefulness of the methodological framework presented here lies in the possibility of making more visible the greater number of benefits that cultural heritage offers to human beings from a tourism perspective. It identifies, on the other side, which are the functions to be preserved or encouraged and which anthropic units are particularly important to adapt, conserve or restore in order to maintain or increase the flow of these services

Once visible through the proposed measurement method, it is more intuitive to assess and demonstrate the viability of the object as an element of tourist attraction and, therefore, the importance of its conservation. From the analysis carried out and the results obtained, the following conclusions can be drawn:

- This classification system could allow better cooperation between institutions and greater multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary collaboration in science and research. It also provides a logical discourse to build bridges between science and public management, between science and society, and between public management and society. The use of the theoretical framework of ecosystem services makes it possible to take advantage of a well-argued and well-established methodological development in science. On the other side, this approach is increasingly accepted in management, even to cross-reference spatial planning criteria, applicable to both natural and anthropogenic elements and systems;

- The main objective of this tool is not to compare the importance between the different categories of services or to establish priorities between them, but to make them visible, both for decision-making and for society;

- Currently, there is no universally accepted aseptic method and completely valid criteria for tourism valuation of heritage. In this sense, the criteria selected for the valuation of the supplying units are not intended to reflect an exact reality about heritage and its tourism value, but rather the intention of the model is to give visibility to those aspects that may be hindering the management towards the enhancement of heritage assets and to mark a path that shows the direction of the steps to follow, in order to achieve the economic viability of cultural assets without undermining their preservation or their social enhancement. This approach can serve as a basis for sectoral studies and analyses on the issues addressed;

- Considering the various perspectives and approaches developed by experts and researchers during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries on heritage conservation, it should be noted that although the model proposed here has been developed from the tourism perspective, whose economic dimension is part of a direct relationship between heritage assets and tourism, this should not be the only or the predominant one. When heritage is considered from an economic perspective, it tends to become a commodity, an object of consumption, which is one of the main threats to heritage: the loss of its meaning or significance;

- For this reason, during the configuration of the TPIH-SE index, we have sought to integrate the value of the original, complementary, and potential uses of the heritage assets and the value of the selected criteria from a tourism perspective in order to obtain a holistic view of the possibilities of their enhancement. All this must be done without limiting the approach to new economic opportunities, but also from the opportunities that an improvement in management can mean for the dissemination and social awareness of heritage through tourism, as a tool to bring certain heritage assets to the population and foster a sense of belonging to certain assets in danger of disappearing;

- The process of developing the model includes the following difficulty: associating defined services with benefits for society, since many are intangible. An example of what is considered is that in some cases they depend on the principles, beliefs, experiences, and values of each individual;

- The proposed methodology focuses mainly on tangible or instrumental elements based on services. Including the intangible dimension to the methodology (e.g., the building as an identity image or symbol of the territory or its importance for the link between the community and the property), in addition to including the economic and political dimensions, may be an opportunity to obtain a global vision of the building and its surroundings. This approach will be considered in future studies;

- Taking into account the COVID-19 sanitary crisis, cultural assets, as systems that generate services (benefits), should be strengthened and considered, in order to include possible uses adapted to the circumstantial needs of society. The response to the pandemic should be directed towards the inclusion of measures aimed at meeting the challenges of sustainable development, including the preservation of historical and cultural heritage and the creation of mechanisms for cooperation between society and culture.

This approach can serve as a basis for sectoral studies and analysis of the issues discussed. This study should therefore be considered as an invitation to reflect and deepen the fundamentals of the valuation of heritage associated with tourism as a study phenomenon and as an opportunity to improve its enhancement.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.G.-O. and G.R.-G.; investigation, J.G.-O. and J.A.C.-R.; methodology, G.R.-G. and J.A.C.-R.; project administration, M.A.-G.; supervision, J.G.-O. and J.A.C.-R.; validation, G.R.-G. and M.A.-G.; writing—original draft, G.R.-G.; writing—review and editing, J.G-O., M.A.-G., and J.A.C.-R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by InnovaConcrete Project, funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under grant agreement (No. 760858).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We remain grateful the Parroquia del Mar for allowing us to carry out the interviews, an essential step for the validation of the study. We also thank our anonymous reviewers for their advice.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Ballart Hernández, J.; Juan i Tresserras, J. Gestión del Patrimonio Cultural, 4th ed.; Ariel Patrimonio: Barcelona, Spain, 2008; pp. 2–23. [Google Scholar]

- International Centre for the Study of the Preservation and Restoration of Cultural Property (ICCROM). A story of Change. Success Stories and Lessons Learnt from the Culture Cannot Wait: Heritage for Peace and Resilience Project; ICCROM: Roma, Italy, 2021; ISBN 978-92-9077-302-3. Available online: https://www.iccrom.org/sites/default/files/publications/2021-02/astoryofchange.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Zimmer, P.; Grassmann, S. Guía: Evaluar el Potencial Turístico de un Territorio; Observatorio Líder Europeo: Extremadura, Spain, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Blanco, M. Guía Para la Elaboración del Plan de Desarrollo Turístico de un Territorio. 2008. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/15657694/GU%C3%8DA_PARA_LA_ELABORACI%C3%93N_DEL_PLAN_DE_DESARROLLO_TUR%C3%8DSTICO_DE_UN_TERRITORIO_Documento_producido_en_el_marco_del_Convenio_de_colaboraci%C3%B3n_entre_IICA_Costa_Rica_y_el_Programa_de_Desarrollo_Agroindustrial_Rural_PRODAR (accessed on 1 June 2021).

- Calderón-Puerta, D.; Arcila-Garrido, M.; López-Sánchez, J. Methodological Proposal for the Elaboration of a Tourist Potential Index Applied to Historical Heritage. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2020, 15, 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Olivares, D. Los Recursos Turísticos. Evaluación, Ordenación y Planificación Turística. Estudio de Casos; Tirant Humanidades: Valencia, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Reyes Morales, R.G.; Naude, A.Y.; Cruz, A.S.G.; Hinojosa-Ojeda, R.; Martínez, R.R. Los Actores Sociales Frente Al Desarrollo Rural. Nueva Rural. Viejos Probl. 2005, 24, 223–275. [Google Scholar]

- Cary, S.H. The tourist moment. Ann. Tour. Res. 2004, 31, 61–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Guerrero, G.; García-Onetti, J.; Chica-Ruiz, J.A.; Arcila-Garrido, M. Concrete as heritage: The social perception from heritage criteria perspective. The Eduardo Torroja’s work. Int. J. Des. Nat. Ecodynamics 2020, 15, 785–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pralong, J.-P. A method for assessing tourist potential and use of geomorphological sites. Géomorphologie Relief Process. Environ. 2005, 11, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Mamun, A.; Mitra, S. A methodology for assessing tourism potential: Case study Murshidabad District, West Bengal, India. Int. J. Sci. Res. Publ. 2012, 2, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Puška, A.; Pamucar, D.; Stojanović, I.; Cavallaro, F.; Kaklauskas, A.; Mardani, A. Examination of the Sustainable Rural Tourism Potential of the Brčko District of Bosnia and Herzegovina Using a Fuzzy Approach Based on Group Decision Making. Sustainability 2021, 13, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willemen, L.; Cottam, A.J.; Drakou, E.G.; Burgess, N.D. Using social media to measure the contribution of red list species to the nature-based tourism potential of African protected areas. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0129785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaynak, E.; Bloom, J.; Leibold, M. Using the Delphi Technique to Predict Future Tourism Potential. Mark. Intell. Plan. 1994, 12, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins-Kreiner, N.; Wall, G. Evaluating tourism potential: A SWOT analysis of the Western Negev, Israel. Turiz. Međunarodni Znan. -Stručni Časopis 2007, 55, 51–63. [Google Scholar]

- Cong, L.C. A formative model of the relationship between destination quality, tourist satisfaction and intentional loyalty: An empirical test in Vietnam. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2016, 26, 50–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Gao, B.W.; Zhang, M. A mathematical model for tourism potential assessment. Tour. Manag. 2017, 63, 355–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerner, H. Alois Riegl: Art, value, and historicism. Daedalus 1976, 105, 177–188. [Google Scholar]

- Riegl, A.; Rubió, I.S.-M. Problemas de Estilo: Fundamentos Para una Historia de la Ornamentación; Editorial Gustavo Gili: Barcelona, Spain, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Choay, F. L’Allegorie du Patrimoine, 2007th ed.; Éditions du Seuil: Barcelona, Spain, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Jokilehto, J. History of Architectural Conservation; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- De Guevara Ladrón, B. Valores patrimoniales, la perspectiva del actor social: La historia de Manuel y su barrio patrimonial. Val. MAGAR 2016, 2, 89–100. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, P.S.Y.; McKercher, B. Managing heritage resources as tourism products. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2004, 9, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiper, N. The framework of tourism: Towards a definition of tourism, tourist, and the tourist industry. Ann. Tour. Res. 1979, 6, 390–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.C.; Sirakaya, E. Sustainability indicators for managing community tourism. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 1274–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabeza Monteira, Á.; Seguel Quintana, R. Conservar, conservación, restauración y patrimonio. Rev. de Conserv. Restauración y Patrimonio. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giménez, J.F.N. La Conservación del Patrimonio Arquitectónico. Debates heredados del siglo XX. Available online: https://ojs.uv.es/index.php/arslonga/article/view/11774/11081 (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Dezzi Bardeschi, M. Conservar, no restaurar. Hugo, Ruskin, Boito, Dehio et al. Breve historia y sugerencias para la conservación en este milenio. Loggia Arquit. Restauración 2005, 17, 16–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, N.C.; Price, T.V. Historical and Philosophical Issues in the Conservation of Cultural Heritage; Getty Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1996; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Boito, C. Carta del Restauro. Restauro 1883, 10, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia Canclini, N. Los Usos Sociales del Patrimonio Cultural. Patrimonio Etnológico Nuevas Perspectivas de Estudio, Consejería de Cultura; Junta de Andalucía: Granada, Spain, 1999; pp. 16–33. [Google Scholar]

- Bottero, M.; D’Alpaos, C.; Oppio, A. Ranking of adaptive reuse strategies for abandoned industrial heritage in vulnerable contexts: A multiple criteria decision aiding approach. Sustainability 2019, 11, 785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chronis, A. Coconstructing heritage at the Gettysburg storyscape. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 386–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viollet-LeDuc, E.E. The Architectural Theory of Viollet-le-Duc: Readings and Commentary; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Sitte, C. The Art of Building Cities: City Building According to Its Artistic Fundamentals; Ravenio Books: New Yok, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Baudrillard, J.; Proto, F. Mass, Identity, Architecture: Architectural Writings of Jean Baudrillard; Wiley Academy: Chichester, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ichumbaki, E.B.; Lubao, C.B. Lubao Musicalizing heritage and heritagizing music for enhancing community awareness of preserving world heritage sites in Africa. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2020, 26, 415–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipe, W.D. Value and meaning in cultural resources. Approaches Archaeol. Herit. 1984, 1, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Garau, C. Tecnologías Emergentes y Turismo Cultural: Oportunidades Para Una Agenda de Investigación en Turismo Urbano Cultural. En Turismo en la Ciudad; Springer: Cham, Germany, 2017; pp. 67–80. [Google Scholar]

- Tung, V.W.S.; Ritchie, J.R.B. Exploring the essence of memorable tourism experiences. Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 1367–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timothy, D.J. Tourism and the personal heritage experience. Ann. Tour. Res. 1997, 24, 751–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laing, J.; Wheeler, F.; Reeves, K.; Frost, W. Assessing the experiential value of heritage assets: A case study of a Chinese heritage precinct, Bendigo, Australia. Tour. Manag. 2014, 40, 180–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcinkevičiūtė, L.; Pranskūnienė, R. Cultural Ecosystem Services: The Case of Coastal-Rural Area (Nemunas Delta and Curonian Lagoon, Lithuania). Sustainability 2021, 13, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boniotti, C. The public–private–people partnership (P4) for cultural heritage management purposes. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Turo, F.; Medeghini, L. How Green Possibilities Can Help in a Future Sustainable Conservation of Cultural Heritage in Europe. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations (UN). Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/21252030%20Agenda%20for%20Sustainable%20Development%20web.pdf (accessed on 24 May 2021).

- Parga-Dans, E.; Alonso González, P. Sustainable tourism and social value at World Heritage Sites: Towards a conservation plan for Altamira, Spain. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 74, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Special Eurobarometer 466: Cultural Heritage. Brussels: Directorate-General for Communication; Data.europa.eu: Brussels, Belgium, 2017; Available online: https://data.europa.eu/data/datasets/s2150_88_1_466_eng?locale=en (accessed on 15 April 2021).

- Council of Europe. Council of Europe Framework Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society. The Faro Convention; Council of Europe Publications: Faro, Portual, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Dragouni, M.; Fouseki, K. Drivers of community participation in heritage tourism planning: An empirical investigation. J. Herit. Tour. 2018, 13, 237–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogan, H.A. Assessment of the perception of cultural heritage as an adaptive re-use and sustainable development strategy: Case study of Kaunas, Lithuania. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 9, 430–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ecosystem Assessment, Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: Biodiversity Synthesis; World Resources Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2005.

- Scorza, F.; Murgante, B.; Las Casas, G.; Fortino, Y.; Pilogallo, A. Investigating Territorial Specialization in Tourism Sector by Ecosystem Services Approach. In Ciudades Mediterráneas y Comunidades Insulares; Springer: Cham, Germany, 2019; pp. 161–179. [Google Scholar]

- De Groot, R.S.; Wilson, M.A.; Boumans, R.M. A typology for the classification, description and valuation of ecosystem functions, goods and services. Ecol. Econ. 2002, 41, 393–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Baggethun, E.; De Groot, R.; Lomas, P.L.; Montes, C. The history of ecosystem services in economic theory and practice: From early notions to markets and payment schemes. Ecol. Econ. 2010, 69, 1209–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcila-Garrido, M.; Benítez López, D.; Chica Ruiz, A.; García Onetti, J.; Ramírez Guerrero, G. Plan Design: Ecosystem services approach methodology. Typological classification. Methodology and indicators. INNOVACONCRETE Project (H2020). Appl. Geogr. 2019. under review. [Google Scholar]

- Komppula, R. Developing the quality of a tourist experience product in the case of nature-based activity services. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2006, 6, 136–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingerpuu, L. Socialist architecture as today’s dissonant heritage: Administrative buildings of collective farms in Estonia. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2018, 24, 954–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banham, R. The New Brutalism; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2011; pp. 19–28. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez Medina, A. Paisaje, Ciudad y Arquitectura Turísticos del Mediterráneo, 1923–1973; Arquitectura Moderna y Turismo: 1925–1965; Fundación DoCoMoMo Ibérico: Barcelona, Spain, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Haines-Young, R.; Potschin, M. Common international classification of ecosystem services (CICES, Version 4.1). Eur. Environ. Agency 2012, 33, 107. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, P.; Earthscan, P. TEEB (The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity); Ecological and Economic Foundation: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- ICOMOS. ICOMOS Conservation of Historic Towns and Urban Areas Charter. Washington Charter. 1987. Available online: https://www.icomos.org/charters/towns_e.pdf (accessed on 17 May 2021).

- Navarro, D. Recursos turísticos y atractivos turísticos: Conceptualización, clasificación y valoración. Cuad. de Tur. 2015, 35, 335–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).