Explanatory Model Based on the Type of Physical Activity, Motivational Climate and Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet of Anxiety among Physical Education Trainee Teachers

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Participants

2.2. Instruments

2.3. Procedure and Ethical Aspects

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Comparative Analysis

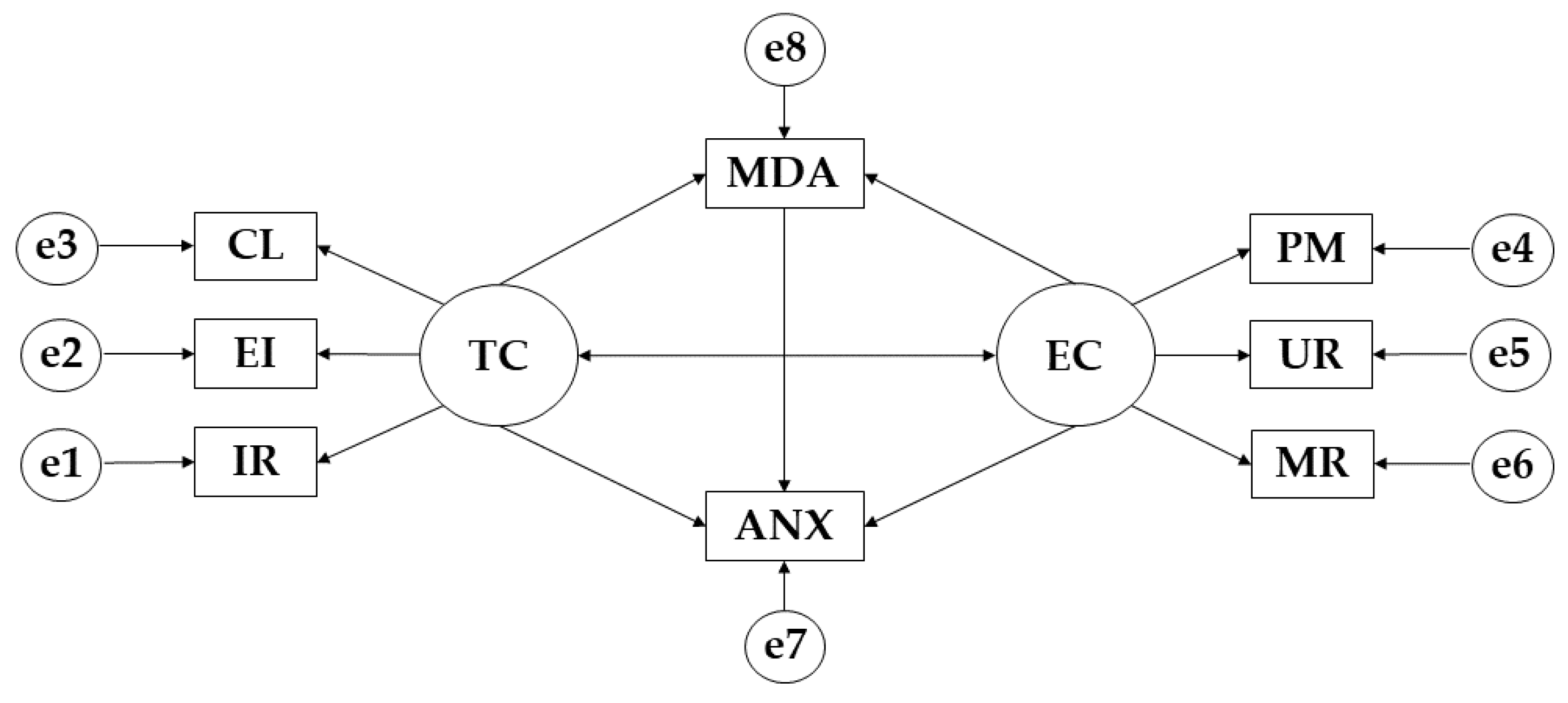

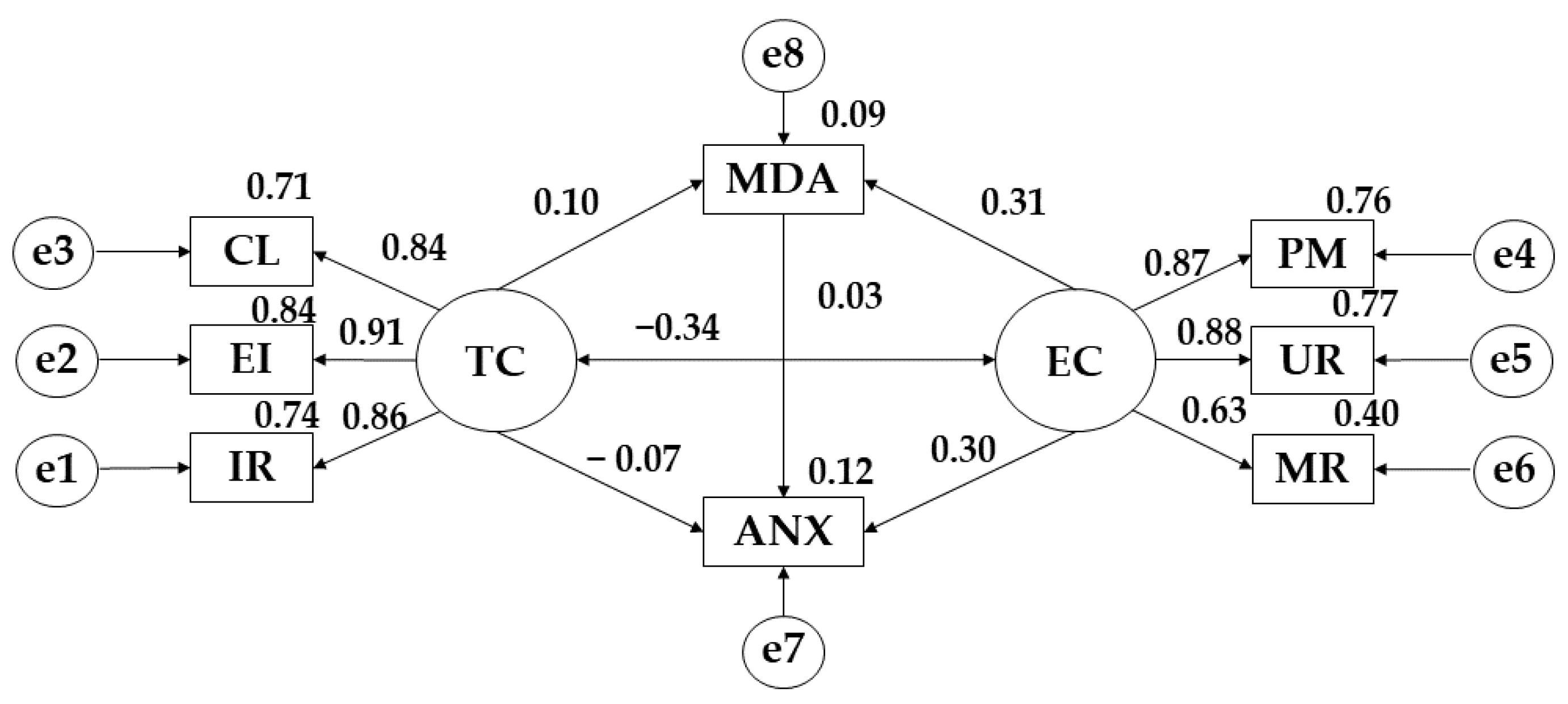

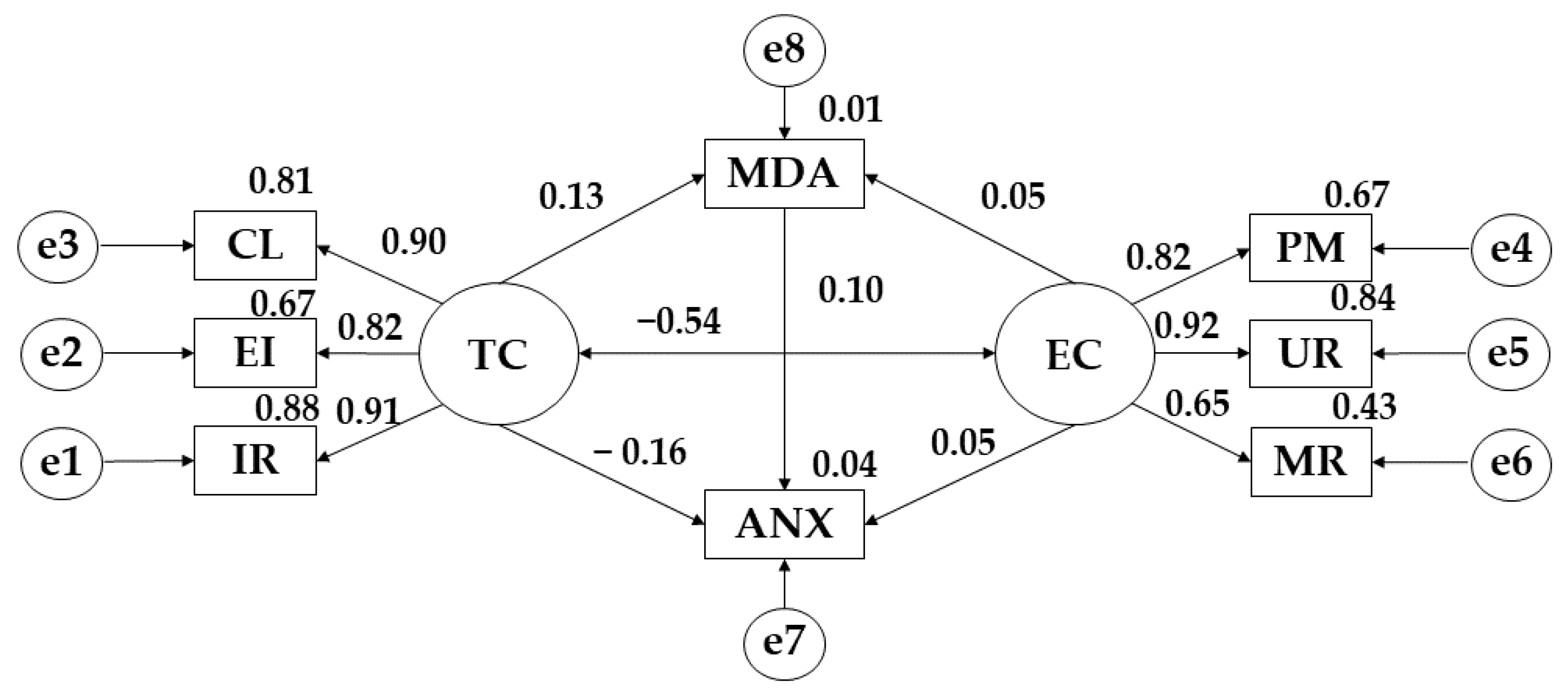

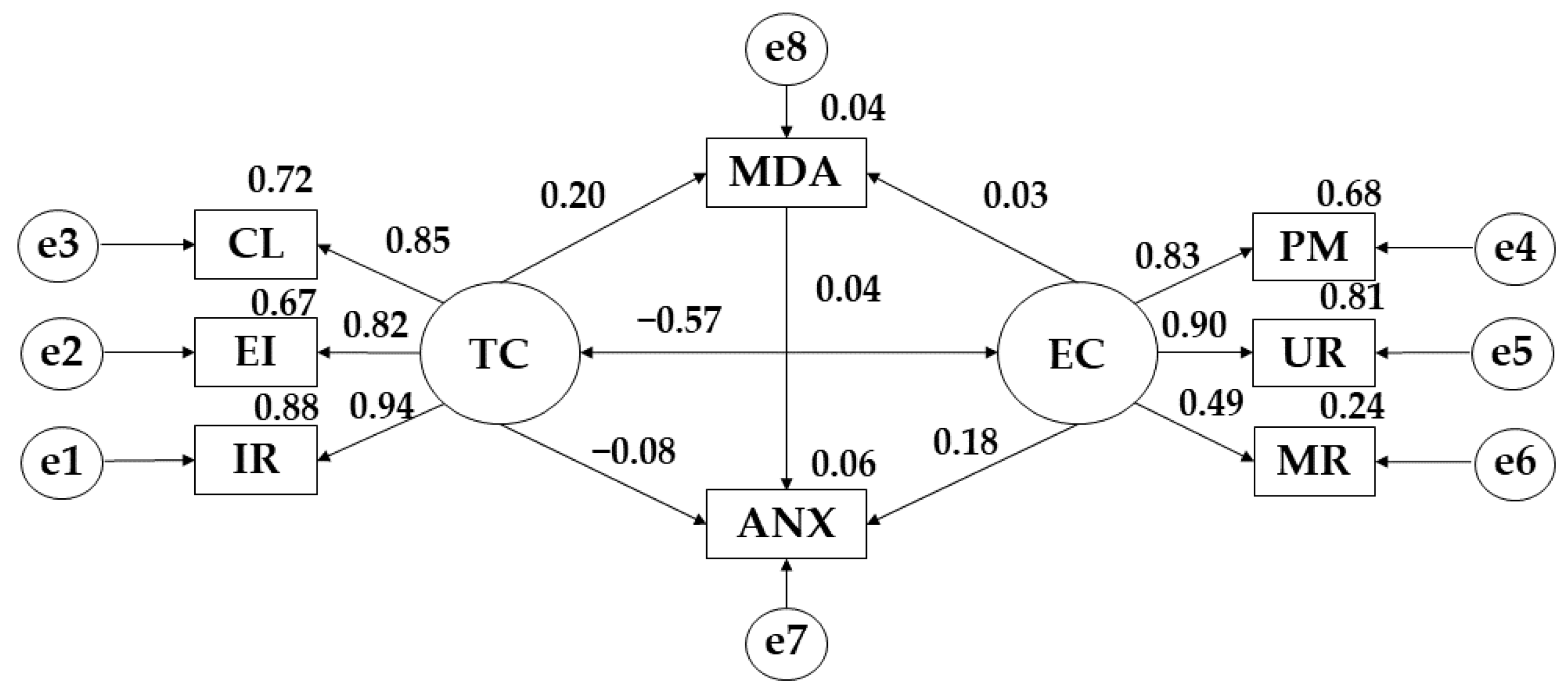

3.2. Structural Equations Model Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Limitations and Future Perspectives

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Allen, M.S.; Robson, D.A.; Vella, S.A.; Laborde, S. Extraversion development in childhood, adolescence and adulthood: Testing the role of sport participation in three nationally-representative samples. J. Sports Sci. 2021, 39, 2258–2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brylka, A.; Wolke, D.; Ludyga, S.; Bilgin, A.; Spiegler, J.; Trower, H.; Gkiouleka, A.; Gerber, M.; Brand, S.; Grob, A.; et al. Physical activity, mental health, and well-being in very pre-term and term born adolescents: An individual participant data meta-analysis of two accelerometry studies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melguizo-Ibáñez, E.; González-Valero, G.; Badicu, G.; Filipa-Silva, A.; Clemente, F.M.; Sarmento, H.; Zurita-Ortega, F.; Ubago-Jiménez, J.L. Mediterranean Diet Adherence, Body Mass Index and Emotional Intelligence in Primary Education Students—An Explanatory Model as a Function of Weekly Physical Activity. Children 2022, 9, 872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Branje, S.; de Moor, E.L.; Spitzer, J.; Becht, A.I. Dynamics of identity development in adolescence: A decade in review. J. Res. Adolesc. 2021, 31, 908–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fröberg, A.; Lundvall, S. The Distinct Role of Physical Education in the Context of Agenda 2030 and Sustainable Development Goals: An Explorative Review and Suggestions for Future Work. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindell-Postigo, D.; Zurita-Ortega, F.; Ortiz-Franco, M.; González-Valero, G. Cross-Sectional Study of Self-Concept and Gender in Relation to Physical Activity and Martial Arts in Spanish Adolescents during the COVID-19 Lockdown. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melguizo-Ibáñez, E.; Viciana-Garófano, V.; Zurita-Ortega, F.; Ubago-Jiménez, J.L.; González-Valero, G. Physical Activity Level, Mediterranean Diet Adherence, and Emotional Intelligence as a Function of Family Functioning in Elementary School Students. Children 2021, 8, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Jurado, J.A. La Actividad Física Orientada a la Promoción de la Salud. Esc. Abierta Rev. Investig. Educ. 2007, 7, 73–96. [Google Scholar]

- Melguizo-Ibáñez, E.; Zurita-Ortega, F.; Ubago-Jiménez, J.L.; Puertas-Molero, P.; González-Valero, G. Motivational Climate, Anxiety and Physical Self-Concept in Trainee Physical Education Teachers—An Explanatory Model Regarding Physical Activity Practice Time. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talamonti, D.; Vincent, T.; Fraser, S.; Nigam, A.; Lesage, F.; Bherer, L. The Benefits of Physical Activity in Individuals with Cardiovascular Risk Factors: A Longitudinal Investigation Using fNIRS and Dual-Task Walking. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Sánchez, E.; Ramírez-Vargas, G.; Avellaneda-López, Y.; Orellana-Pecino, J.I.; García-Marín, E.; Díaz-Jimenez, J. Eating Habits and Physical Activity of the Spanish Population during the COVID-19 Pandemic Period. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vega-Ávila, G.C.; Afanador-Restrepo, D.F.; Rivas-Campo, Y.; García-Garro, P.A.; Hita-Contreras, F.; Carcelén-Fraile, M.d.C.; Castellote-Caballero, Y.; Aibar-Almazán, A. Rhythmic Physical Activity and Global Cognition in Older Adults with and without Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dwyer, M.J.; Pasini, M.; De Dominicis, S.; Righi, E. Physical activity: Benefits and challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2020, 30, 1291–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Espínola, C.; Abad Robles, M.T.; Collado-Mateo, D.; Almagro, B.J.; Castillo Viera, E.; Giménez Fuentes-Guerra, F.J. Effects of Cooperative-Learning Interventions on Physical Education Students’ Intrinsic Motivation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lochbaum, M.; Zanatta, T.; Kazak, Z. The 2 × 2 Achievement Goals in Sport and Physical Activity Contexts: A Meta-Analytic Test of Context, Gender, Culture, and Socioeconomic Status Differences and Analysis of Motivations, Regulations, Affect, Effort, and Physical Activity Correlates. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2020, 10, 173–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Melguizo-Ibáñez, E.; Zurita-Ortega, F.; Ubago-Jiménez, J.L.; López-Gutiérrez, C.J.; González-Valero, G. An explanatory model of the relationships between sport motivation, anxiety and physical and social self-concept in educational sciences students. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, J.G. The Competitive Ethos and Democratic Education; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Ames, C. Classrooms: Goals, structures, and student motivation. J. Educ. Psychol. 1992, 84, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chacón-Cuberos, R.; Badicu, G.; Zurita-Ortega, F.; Castro-Sánchez, M. Mediterranean Diet and Motivation in Sport: A Comparative Study Between University Students from Spain and Romania. Nutrients 2019, 11, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- González-Valero, G.; Zurita-Ortega, F.; Martínez-Martínez, A. Panorama motivacional y de actividad física en estudiantes: Una revisión sistemática. ESHPA 2017, 1, 41–58. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10481/48961 (accessed on 1 December 2022).

- Burkova, V.N.; Butovskaya, M.L.; Randall, A.K.; Fedenok, J.N.; Ahmadi, K.; Alghraibeh, A.M.; Allami, F.B.M.; Alpaslan, F.S.; Al-Zu’bi, M.A.A.; Biçer, D.F.; et al. Predictors of Anxiety in the COVID-19 Pandemic from a Global Perspective: Data from 23 Countries. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Sun, Q.; Zhai, L.; Bai, Y.; Wei, W.; Jia, L. The Prevalence of Depression and Anxiety Symptoms among Overweight/Obese and Non-Overweight/Non-Obese Children/Adolescents in China: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Romero-Pérez, E.M.; González-Bernal, J.J.; Soto-Cámara, R.; González-Santos, J.; Tánori-Tapia, J.M.; Rodríguez-Fernández, P.; Jiménez-Barrios, M.; Márquez, S.; de Paz, J.A. Influence of a Physical Exercise Program in the Anxiety and Depression in Children with Obesity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.-Y.; Tsai, M.-C.; Liu, C.-H.; Lin, Y.-C.; Hsieh, Y.-P.; Strong, C. Psychological Pathway from Obesity-Related Stigma to Anxiety via Internalized Stigma and Self-Esteem among Adolescents in Taiwan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fausnacht, D.W.; McMillan, R.P.; Boutagy, N.E.; Lupi, R.A.; Harvey, M.M.; Davy, B.M.; Davy, K.P.; Rhoads, R.P.; Hulver, M.W. Overfeeding and Substrate Availability, But Not Age or BMI, Alter Human Satellite Cell Function. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Favieri, F.; Marini, A.; Casagrande, M. Emotional Regulation and Overeating Behaviors in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Behav. Sci. 2021, 11, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muros, J.J.; Cofre-Bolados, C.; Arriscado, D.; Zurita, F.; Knox, E. Mediterranean diet adherence is associated with lifestyle, physical fitness, and mental wellness among 10-y-olds in Chile. Nutrition 2017, 35, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Melguizo-Ibáñez, E.; Zurita-Ortega, F.; Ubago-Jiménez, J.L.; González-Valero, G. Niveles de adherencia a la dieta mediterránea e inteligencia emocional en estudiantes del tercer ciclo de educación primaria de la provincia de Granada. Retos 2020, 40, 264–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raeside, R.; Partridge, S.R.; Singleton, A.; Redfern, J. Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Adolescents: eHealth, Co-Creation, and Advocacy. Med. Sci. 2019, 7, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Beck, A.T.; Epstein, N.; Brown, G.; Steer, R.A. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: Psychometric properties. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1988, 56, 893–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz, J.; Navarro, M.E. Propiedades psicométricas de una versión española del Inventario de Ansiedad de Beck (BAI) en estudiantes universitarios. Ansiedad Estrés 2003, 9, 59–84. [Google Scholar]

- Newton, M.; Duda, J.L.; Yin, Z. Examination of the psychometric properties of the perceived motivational climate in sport questionnaire-2 in a sample of female athletes. J. Sports Sci. 2000, 18, 275–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Cutre, D.; Sicilia, A.; Moreno, J. Modelo cognitivo-social de la motivación de logro en educación física. Psicothema 2008, 20, 642–651. [Google Scholar]

- Schröder, H.; Fitó, M.; Estruch, R.; Martínez-González, M.A.; Corella, D.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.; Ros, E.; Salaverría, I.; Fiol, M.; et al. A short screener is valid for assessing Mediterranean diet adherence among older Spanish men and women. J. Nutr. 2011, 141, 1140–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Álvarez-Álvarez, I.; Martínez-González, M.; Sánchez-Tainta, A.; Corella, D.; Díaz-López, A.; Fitó, M.; Vioque, J.; Romaguera, D.; Martínez, J.A.; Wärnberg, J.; et al. Dieta mediterránea hipocalórica y factores de riesgo cardiovascular: Análisis transversal de PREDIMED-Plus. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 2019, 72, 925–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mantilla-Toloza, S.C.; Gómez-Conesa, A. El cuestionario Internacional de Actividad Física. Un instrumento adecuado para el seguimiento de la actividad física poblacional. Rev. Iberoam. Fisioter. Kinesol. 2007, 10, 48–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. A power primer. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 112, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P.M. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychol. Bull. 1990, 107, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, R.P.; Marsh, H.W. Choosing a multivariate model: Noncentrality and goodness of fit. Psychol. Bull. 1990, 107, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriazos, T.A. Applied Psychometrics: Sample Size and Sample Power Considerations in Factor Analysis (EFA, CFA) and SEM in General. Psychology 2018, 9, 2207–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tenenbaum, G.; Eklund, R.C. Handbook of Sport Psychology; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonofiglio, D. Mediterranean Diet and Physical Activity as Healthy Lifestyles for Human Health. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malakou, E.; Linardakis, M.; Armstrong, M.E.G.; Zannidi, D.; Foster, C.; Johnson, L.; Papadaki, A. The Combined Effect of Promoting the Mediterranean Diet and Physical Activity on Metabolic Risk Factors in Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ali, H.I.; Attlee, A.; Alhebshi, S.; Elmi, F.; Al Dhaheri, A.S.; Stojanovska, L.; El Mesmoudi, N.; Platat, C. Feasibility Study of a Newly Developed Technology-Mediated Lifestyle Intervention for Overweight and Obese Young Adults. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ubago-Jiménez, J.L.; Zurita-Ortega, F.; San Román-Mata, S.; Puertas-Molero, P.; González-Valero, G. Impact of Physical Activity Practice and Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet in Relation to Multiple Intelligences among University Students. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paolucci, E.M.; Loukov, D.; Bowdish, D.M.E.; Heisz, J.J. Exercise reduces depression and inflammation but intensity matters. Biol. Psychol. 2018, 133, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Sánchez, M.; Zurita-Ortega, F.; García-Marmol, E.; Chacón-Cuberos, R. Motivational Climate towards the Practice of Physical Activity, Self-Concept, and Healthy Factors in the School Environment. Sustainability 2019, 11, 999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- González-Valero, G.; Ubago-Jiménez, J.L.; Ramírez-Granizo, I.A.; Puertas-Molero, P. Association between Motivational Climate, Adherence to Mediterranean Diet, and Levels of Physical Activity in Physical Education Students. Behav. Sci. 2019, 9, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Castro-Sánchez, M.; Zurita-Ortega, F.; García-Marmol, E.; Chacón-Cuberos, R. Motivational Climate in Sport Is Associated with Life Stress Levels, Academic Performance and Physical Activity Engagement of Adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kokkonen, J.; Gråstén, A.; Quay, J.; Kokkonen, M. Contribution of Motivational Climates and Social Competence in Physical Education on Overall Physical Activity: A Self-Determination Theory Approach with a Creative Physical Education Twist. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobo-Cuenca, A.I.; Garrido-Miguel, M.; Soriano-Cano, A.; Ferri-Morales, A.; Martínez-Vizcaíno, V.; Martín-Espinosa, N.M. Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet and Its Association with Body Composition and Physical Fitness in Spanish University Students. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- González-Valero, G.; Zurita-Ortega, F.; Chacón-Cuberos, R.; Puertas-Molero, P. Analysis of Motivational Climate, Emotional Intelligence, and Healthy Habits in Physical Education Teachers of the Future Using Structural Equations. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Orumiyehei, A.; Khoramipour, K.; Rezaei, M.H.; Madadizadeh, E.; Meymandi, M.S.; Mohammadi, F.; Chamanara, M.; Bashiri, H.; Suzuki, K. High-Intensity Interval Training-Induced Hippocampal Molecular Changes Associated with Improvement in Anxiety-like Behavior but Not Cognitive Function in Rats with Type 2 Diabetes. Brain Sci. 2022, 12, 1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trigueros, R.; Padilla, A.M.; Aguilar-Parra, J.M.; Rocamora, P.; Morales-Gázquez, M.J.; López-Liria, R. The Influence of Emotional Intelligence on Resilience, Test Anxiety, Academic Stress and the Mediterranean Diet. A Study with University Students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- López-Olivares, M.; Mohatar-Barba, M.; Fernández-Gómez, E.; Enrique-Mirón, C. Mediterranean Diet and the Emotional Well-Being of Students of the Campus of Melilla (University of Granada). Nutrients 2020, 12, 1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| N | M | SD | F | P | ES | 95%CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MDA | Low | 128 | 0.48 | 0.135 | 4.095 | ≤0.05 b | 0.318 b | [0.107; 0.530] b |

| Moderate | 169 | 0.50 | 0.121 | |||||

| High | 271 | 0.52 | 0.123 | |||||

| ANX | Low | 128 | 0.97 | 0.699 | 7.688 | ≤0.05 a,b | 0.332 a 0.403 b | [0.101; 0.563] a [0.191; 0.615] b |

| Moderate | 170 | 0.77 | 0.582 | |||||

| High | 271 | 0.71 | 0.618 | |||||

| CL | Low | 128 | 3.80 | 1.018 | 6.509 | ≤0.05 b | 0.399 b | [0.187; 0.611] b |

| Moderate | 170 | 4.00 | 0.876 | |||||

| High | 271 | 4.14 | 0.762 | |||||

| EI | Low | 128 | 3.77 | 0.844 | 5.011 | ≤0.05 a,b | 0.280 a 0.329 b | [0.05; 0.511] a [0.116; 0.542] b |

| Moderate | 170 | 3.98 | 0.670 | |||||

| High | 271 | 4.01 | 0.665 | |||||

| IR | Low | 128 | 3.86 | 0.926 | 5.280 | ≤ 0.05 b | 0.359 b | [0.148; 0.571] b |

| Moderate | 170 | 4.03 | 0.895 | |||||

| High | 271 | 4.15 | 0.745 | |||||

| PM | Low | 128 | 2.32 | 0.819 | 0.779 | ≥0.05 | NP | NP |

| Moderate | 170 | 2.44 | 0.823 | |||||

| High | 271 | 2.38 | 0.770 | |||||

| UR | Low | 128 | 2.72 | 1.049 | 0.487 | ≥0.05 | NP | NP |

| Moderate | 170 | 2.72 | 1.020 | |||||

| High | 271 | 2.64 | 1.015 | |||||

| MR | Low | 128 | 2.63 | 0.890 | 1.029 | ≥0.05 | NP | NP |

| Moderate | 170 | 2.78 | 0.883 | |||||

| High | 271 | 2.73 | 0.935 | |||||

| Associations between Variables | R.W. | S.R.W. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimations | S.E. | C.R. | p | Estimations | |

| MDA ← TC | 0.036 | 0.014 | 2.490 | ** | 0.101 |

| MDA ← EC | 0.006 | 0.016 | 0.344 | 0.731 | 0.310 |

| IR ← TC | 1.000 | 0.859 | |||

| EI ← TC | 0.775 | 0.044 | 17.649 | *** | 0.914 |

| CL ← TC | 0.925 | 0.049 | 18.848 | *** | 0.840 |

| PM ← EC | 1.000 | 0.869 | |||

| UR ← EC | 1.440 | 0.112 | 12.833 | *** | 0.880 |

| MR ← EC | 0.715 | 0.093 | 7.735 | *** | 0.631 |

| ANX ← MDA | 0.189 | 0.308 | 0.613 | ** | 0.030 |

| ANX ← TC | −0.069 | 0.073 | −0.953 | 0.341 | −0.068 |

| ANX ← EC | 0.177 | 0.081 | 2.191 | ** | 0.303 |

| EC ←→ TC | −0.255 | 0.037 | −6.846 | *** | −0.342 |

| Associations between Variables | R.W. | S.R.W. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimations | S.E. | C.R. | p | Estimations | |

| MDA ← TC | 0.019 | 0.015 | 1.293 | 0.196 | 0.128 |

| MDA ← EC | 0.010 | 0.018 | 0.537 | 0.591 | 0.054 |

| IR ← TC | 1.000 | 0.911 | |||

| EI ← TC | 0.672 | 0.048 | 14.057 | *** | 0.816 |

| CL ← TC | 0.970 | 0.059 | 16.406 | *** | 0.899 |

| PM ← EC | 1.000 | 0.817 | |||

| UR ← EC | 1.402 | 0.122 | 11.487 | *** | 0.918 |

| MR ← EC | 0.858 | 0.097 | 8.873 | *** | 0.654 |

| ANX ← TC | −0.114 | 0.070 | −1.636 | ** | −0.160 |

| ANX ← EC | 0.046 | 0.085 | 0.541 | 0.589 | 0.053 |

| ANX ← MDA | 0.475 | 0.365 | 1.301 | ** | 0.099 |

| EC ←→ TC | −0.296 | 0.056 | −5.303 | *** | −0.541 |

| Associations between Variables | R.W. | S.R.W. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimations | S.E. | C.R. | p | Estimations | |

| MDA ←TC | 0.036 | 0.014 | 2.490 | ** | 0.204 |

| MDA ←EC | 0.006 | 0.016 | 0.344 | 0.731 | 0.029 |

| IR ←TC | 1.000 | 0.938 | |||

| EI ←TC | 0.775 | 0.044 | 17.649 | *** | 0.816 |

| CL ←TC | 0.925 | 0.049 | 18.848 | *** | 0.848 |

| PM ←EC | 1.000 | 0.826 | |||

| UR ←EC | 1.440 | 0.112 | 12.833 | *** | 0.900 |

| MR ← EC | 0.715 | 0.093 | 7.735 | *** | 0.488 |

| ANX ←MDA | 0.189 | 0.308 | 0.613 | 0.540 | 0.038 |

| ANX ←TC | −0.069 | 0.073 | −0.953 | 0.341 | −0.078 |

| ANX ←EC | 0.177 | 0.081 | 2.191 | ** | 0.183 |

| EC ←→TC | −0.255 | 0.037 | −6.846 | *** | −0.574 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Melguizo-Ibáñez, E.; González-Valero, G.; Puertas-Molero, P.; Zurita-Ortega, F.; Ubago-Jiménez, J.L.; Alonso-Vargas, J.M. Explanatory Model Based on the Type of Physical Activity, Motivational Climate and Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet of Anxiety among Physical Education Trainee Teachers. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 13016. https://doi.org/10.3390/app122413016

Melguizo-Ibáñez E, González-Valero G, Puertas-Molero P, Zurita-Ortega F, Ubago-Jiménez JL, Alonso-Vargas JM. Explanatory Model Based on the Type of Physical Activity, Motivational Climate and Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet of Anxiety among Physical Education Trainee Teachers. Applied Sciences. 2022; 12(24):13016. https://doi.org/10.3390/app122413016

Chicago/Turabian StyleMelguizo-Ibáñez, Eduardo, Gabriel González-Valero, Pilar Puertas-Molero, Félix Zurita-Ortega, José Luis Ubago-Jiménez, and José Manuel Alonso-Vargas. 2022. "Explanatory Model Based on the Type of Physical Activity, Motivational Climate and Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet of Anxiety among Physical Education Trainee Teachers" Applied Sciences 12, no. 24: 13016. https://doi.org/10.3390/app122413016

APA StyleMelguizo-Ibáñez, E., González-Valero, G., Puertas-Molero, P., Zurita-Ortega, F., Ubago-Jiménez, J. L., & Alonso-Vargas, J. M. (2022). Explanatory Model Based on the Type of Physical Activity, Motivational Climate and Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet of Anxiety among Physical Education Trainee Teachers. Applied Sciences, 12(24), 13016. https://doi.org/10.3390/app122413016