Developments and Prospects in Imperative Underexploited Vegetable Legumes Breeding: A Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Crop Wild Relatives

2.1. Vegetable Pigeon Pea (Cajanus cajan)

2.2. Cluster Bean (Cyamopsis Tetragonoloba)

2.3. Winged Bean (Psophocarpus tetragonolobus)

2.4. Dolichos Bean (Lablab purpureus)

2.5. Cowpea (Vigna Unguiculata)

3. Pre-Breeding

4. Molecular Markers from Diversity to QTLs

5. Genomic and Transcriptomic Resources

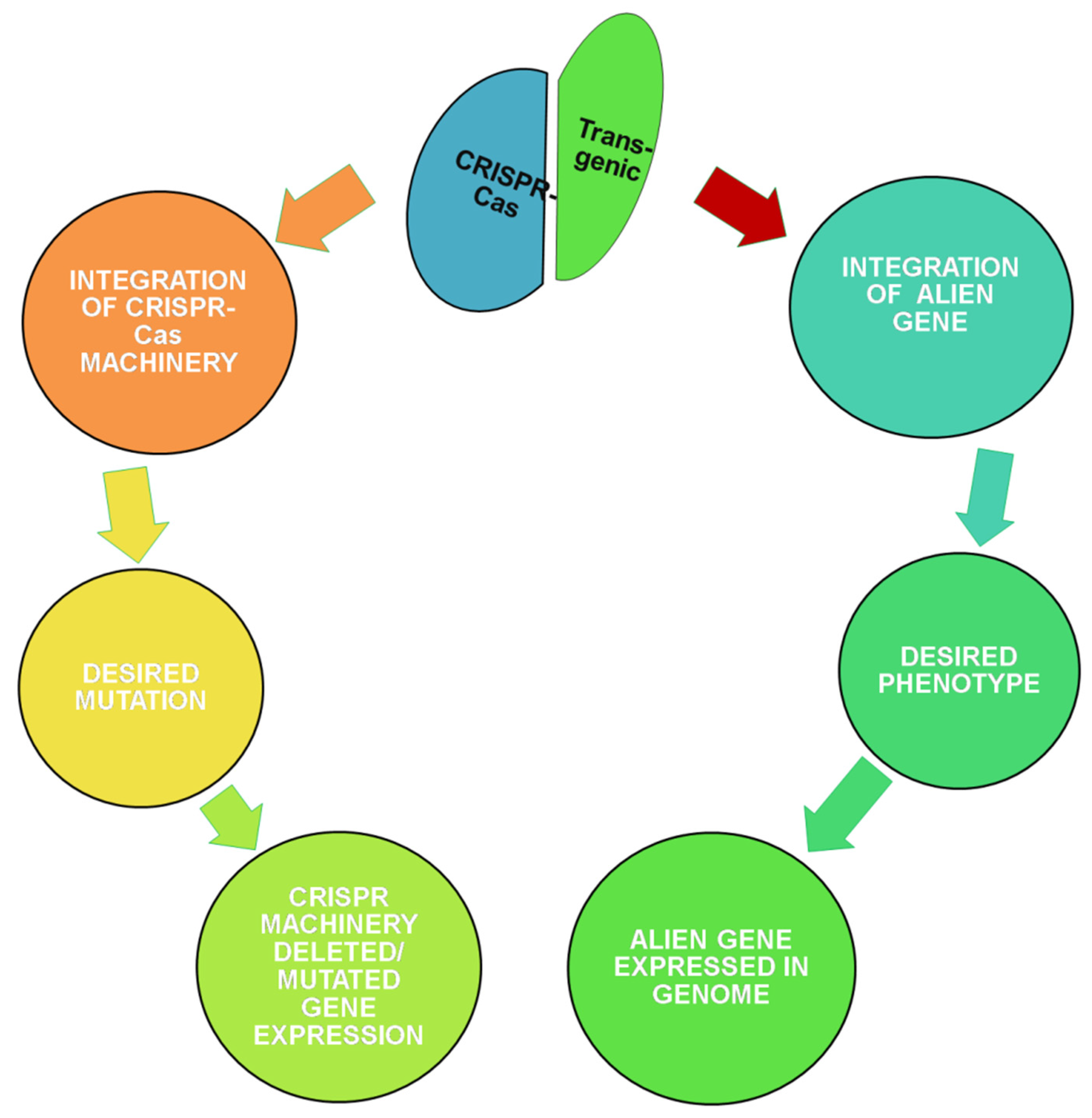

6. Transgenics and Genome Editing

7. Future Prospects

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| QTLs | Quantitative trait loci |

| NGS | Next-generation sequencing |

| CWRs | Crop wild relatives |

| RFLP | Restriction fragment length polymorphism |

| RAPD | Random amplification of polymorphic DNA |

| AFLP | Amplified fragment length polymorphism |

| SSRs | Simple sequence repeats |

| SNPs | Single nucleotide polymorphism |

| EST | Expressed sequence tag |

| ISSR | Inter simple sequence repeat |

| NCBI | National Center for Biotechnology Information |

| GWAS | Genome-wide association studies |

| SLAF | Specific length amplified fragment sequencing |

| GBS | Genotyping-by-sequencing |

| WBLRP | Winged bean lysine-rich protein |

| RNAi | RNA interference |

| HEs | Homing endonucleases |

| ZFNs | Zinc finger nucleases |

| CRISPR-Cas | Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat and CRISPR-associated protein |

| HDR | Homology directed repair |

| GVR | Geminivirus replicon |

References

- Godfray, H.C.J.; Beddington, J.R.; Crute, I.R.; Haddad, L.; Lawrence, D.; Muir, J.F.; Pretty, J.; Robinson, S.; Thomas, S.M.; Toulmin, C. Food security: The challenge of feeding 9 billion people. Science 2010, 327, 812–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palai, J.B.; Jena, J.; Maitra, S. Prospects of underutilized food legumes in sustaining pulse needs in India–A review. Crop. Res. 2019, 54, 82–88. [Google Scholar]

- Harouna, D.V.; Venkataramana, P.B.; Ndakidemi, P.A.; Matemu, A.O. Under-exploited wild Vigna species potentials in human and animal nutrition: A review. Glob. Food Sec. 2018, 18, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A.; Pandey, A.; Varaprasad, K.S.; Tyagi, R.K.; Khetarpal, R.K. Regional expert consultation on underutilized crops for food and nutrition security in asia and the pacific. IJPGR 2018, 31, 194–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clydesdale, F. Functional foods: Opportunities & challenges. Food Technol. 2004, 58, 35–40. [Google Scholar]

- Mall, T.P. Diversity of potential orphan plants in health management and climate change mitigation from Bahraich (Uttar Pradesh). Int. J. Curr. Res. Biosci. Plant Biol. 2017, 4, 106–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabhaudhi, T.; Chimonyo, V.G.; Chibarabada, T.P.; Modi, A.T. Developing a roadmap for improving neglected and underutilized crops: A case study of South Africa. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, M.W.; Wu, X.; Bhandari, D.; Zhang, X.; Hao, J. Role of legumes for and as horticultural crops in sustainable agriculture. In Organic Farming for Sustainable Agriculture; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 185–211. [Google Scholar]

- Krupa, U. Main nutritional and antinutritional compounds of bean seeds-a review. Polish J. Food Nutr. Sci. 2008, 58, 149–155. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, V.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Kumar, R.; Kumar, A.; Ibañez, F.; Wang, J.; Guo, B.; Sudini, H.K.; Gopalakrishnan, S.; DasGupta, M.; et al. Molecular Basis of Root Nodule Symbiosis between Bradyrhizobium and ‘Crack-Entry’Legume Groundnut (Arachis hypogaea L.). Plants 2020, 9, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, L.H.; Bukhari, S.; Salah-ud-Din, S.; Minhas, R. Response of new guar strains to various row spacings. Pak. J. Agric. Sci. 2012, 49, 469–471. [Google Scholar]

- OchiaiYanagi, S. Properties of winged bean (Psophocarpus tetragonolobus) protein in comparison with soybean (Glycine max) and common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) protein. Agric. Biol. Chem. 1983, 47, 2273–2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, J.D.; Cichy, K.A.; Siddiq, M.; Uebersax, M.A. Dry bean breeding and production technologies. In Dry Beans and Pulses: Production, Processing, and Nutrition; Wiley-Blackwell: Chichester, UK, 2013; pp. 23–54. [Google Scholar]

- Taïbi, K.; Taïbi, F.; Abderrahim, L.A.; Ennajah, A.; Belkhodja, M.; Mulet, J.M. Effect of salt stress on growth, chlorophyll content, lipid peroxidation and antioxidant defence systems in Phaseolus vulgaris L. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2016, 105, 306–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, E. Four-Season Harvest: Organic Vegetables from Your Home Garden all Year Long; Chelsea Green Publishing: Hartford, VM, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sá, A.G.; Moreno, Y.M.; Carciofi, B.A. Plant proteins as high-quality nutritional source for human diet. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 97, 170–184. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, P.; Kaushik, P. Evaluation of genetic diversity in cultivated and exotic germplasm sources of Faba Bean using important morphological traits. BioRxiv 2020, 24, 918284. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, J.; Choudhary, A.K.; Gupta, D.S.; Kumar, S. Towards exploitation of adaptive traits for climate-resilient smart pulses. IJMS 2019, 20, 2971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popoola, J.; Ojuederie, O.; Omonhinmin, C.; Adegbite, A. Neglected and underutilized legume crops: Improvement and future prospects. In Recent Advances in Grain Crops Research; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2019; pp. 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- Ertiro, B.T.; Azmach, G.; Keno, T.; Chibsa, T.; Abebe, B.; Demissie, G.; Wegary, D.; Wolde, L.; Teklewold, A.; Worku, M. Fast-tracking the development and dissemination of a drought-tolerant maize variety in Ethiopia in response to the risks of climate change. In The Climate-Smart Agriculture Papers; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 79–86. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, S.; Paul, P.J.; Sameer Kumar, C.V.; Nimje, C. Utilizing Wild Cajanus platycarpus, a Tertiary Genepool Species for Enriching Variability in the Primary Genepool for Pigeonpea Improvement. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulski, J.K. Next-Generation Sequencing—An Overview of the History, Tools, and “Omic” Applications. In Next Generation Sequencing—Advances, Applications and Challenges; Kulski, J.K., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2016; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Ebert, A.W. Potential of underutilized traditional vegetables and legume crops to contribute to food and nutritional security, income and more sustainable production systems. Sustainability 2014, 6, 319–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Relatives, W.C. Genomic and Breeding Resources by Ch. Kole; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hoisington, D.; Khairallah, M.; Reeves, T.; Ribaut, J.M.; Skovmand, B.; Taba, S.; Warburton, M. Plant genetic resources: What can they contribute toward increased crop productivity? Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 5937–5943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, C.N., Jr. Genetically Modified Planet: Environmental Impacts of Genetically Engineered Plants; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Saxena, K.; Chauhan, Y.; Sameer Kumar, C.V.; Hingane, A.; Kumar, R.; Saxena, R.; Rao, G.V.R. Developing Improved Varieties of Pigeonpea, In Achieving Sustainable Cultivation of Grain Legumes Volume 2: Improving Cultivation of Particular Grain Legumes; Sivasankar, S., Ed.; Burleigh Dodds Science Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2018; pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, P.; Singh, I.; Sirari, A.; Khosla, G.; Singh, G.; Ludhar, N.K.; Singh, S. Inheritance and molecular mapping of restorer-of-fertility (Rf) gene in A2 hybrid system in pigeonpea (Cajanus cajan). Plant Breed. 2019, 138, 741–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayenan, M.A.T.; Danquah, A.; Ahoton, L.E.; Ofori, K. Utilization and farmers’ knowledge on pigeonpea diversity in Benin, West Africa. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2017, 13, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hymowitz, T. The trans-domestication concept as applied to guar. Econo. Bot. 1972, 26, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, G.; Reddy, P.S.; Ramteke, P.W.; Rambabu, P.; Tawar, K.B.; Bhattacharya, P. Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation of pigeon pea [Cajanus cajan (L.) Millsp.] for resistance to legume pod borer Helicoverpaarmigera. J. Crop Sci. Biotechnol. 2011, 14, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, A.; Sharma, P.; Saxena, S.; Sharma, R.; Mithra, S.A.; Solanke, A.U.; Singh, N.K.; Sharma, T.R.; Gaikwad, K. The genome size of clusterbean (Cyamopsis tetragonoloba) is significantly smaller compared to its wild relatives as estimated by flow cytometry. Gene 2019, 707, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Grall, A.; Chapman, M.A. Origin and diversification of winged bean (Psophocarpus tetragonolobus (L.) DC.), a multipurpose underutilized legume. Am. J. Bot. 2018, 105, 888–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanzi, A.S.; Eagleton, G.E.; Ho, W.K.; Wong, Q.N.; Mayes, S.; Massawe, F. Winged bean (Psophocarpus tetragonolobus (L.) DC.) for food and nutritional security: Synthesis of past research and future direction. Planta 2019, 250, 911–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, C.S.; Singh, V.; Chapman, M.A. Winged bean: An underutilized tropical legume on the path of improvement, to help mitigate food and nutrition security. Sci. Hortic. 2020, 260, 108789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maass, B.L.; Knox, M.R.; Venkatesha, S.C.; Angessa, T.T.; Ramme, S.; Pengelly, B.C. Lablab purpureus—A Crop Lost for Africa? Trop. Plant Biol. 2010, 3, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rony, M.B.U.; Islam, A.A.; Rasul, M.G.; Zakaria, M. Genetic analysis of yield and related characters of Lablab Bean. J. Nep. Agric. Res. 2019, 5, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, D.M.; Gillespie, N.A.; Martin, N.G. Biometrical genetics. Biol. Psychol. 2002, 61, 33–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maass, B. Domestication, origin and global dispersal of Lablab purpureus (L.) Sweet (Fabaceae): Current understanding. Legume Perspec. 2016, 13, 5–8. [Google Scholar]

- Berthaud, J.; Clément, J.C.; Emperaire, L.; Louette, D.; Pinton, F.; Sanou, J.; Second, G. The Role of Local Level Gene Flow in Enhancing and Maintaining Genetic Diversity. In Broadening the Genetic Base of Crop Production; CABI Publishing in Association with FAO and IPGRI: Wallingford, UK, 2001; pp. 81–103. [Google Scholar]

- Boukar, O.; Fatokun, C. Strategies in cowpea breeding. In New Approaches to Plant Breeding of Orphan Crops in Africa; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2009; pp. 69–92. [Google Scholar]

- Kouam, E.B.; Pasquet, R.S.; Campagne, P.; Tignegre, J.B.; Thoen, K.; Gaudin, R.; Gepts, P. Genetic structure and mating system of wild cowpea populations in West Africa. BMC Plant Biol. 2012, 12, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amorim, L.L.; Ferreira-Neto, J.R.; Bezerra-Neto, J.P.; Pandolfi, V.; de Araújo, F.T.; da Silva Matos, M.K.; Santos, M.G.; Kido, E.A.; Benko-Iseppon, A.M. Cowpea and abiotic stresses: Identification of reference genes for transcriptional profiling by qPCR. Plant Methods 2018, 14, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nwosu, D.J.; Awa, E.N. Cross-compatibility between some cultivated cowpea varieties and a wild relative (subsp. Dekindtiana Var Pubescens). J. Scienti. Res. 2013, 5, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sariah, J.E. Enhancing Cowpea (Vigna Unguiculata L.) Production through Insect pest Resistant Line in East Africa. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Copenhagen, Faculty of Life Sciences, København, Denmark, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson, M.S.; De Vicente, M.C. Gene Flow between Crops and Their Wild Relatives; JHU Press: Baltimore, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Shimelis, H.; Laing, M. Timelines in conventional crop improvement: Pre-breeding and breeding procedures. Aust. J. Crop Sci. 2012, 6, 1542. [Google Scholar]

- Stannard, C.; Moeller, N.I. Identifying Benefit Flows: Studies on the Potential Monetary and Non-Monetary Benefits Arising from the International Treaty on Plant Genetic for food and Agriculture; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis, D.I.; Hodgkin, T. Wild relatives and crop cultivars: Detecting natural introgression and farmer selection of new genetic combinations in agroecosystems. Mol. Ecol. 1999, 8, S159–S173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Upadhyaya, H.D.; Varshney, R.K.; Gowda, C.L.L. Pre-breeding for diversification of primary gene pool and genetic enhancement of grain legumes. Front. Plant Sci. 2013, 4, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nass, L.L.; Paterniani, E. Pre-breeding: A link between genetic resources and maize breeding. Sci. Agric. 2000, 57, 581–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malviya, N.; Yadav, D. RAPD analysis among pigeon pea [Cajanus cajan (L.) Mill sp.] cultivars for their genetic diversity. J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 2010, 1, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Gresta, F.; Mercati, F.; Santonoceto, C.; Abenavoli, M.R.; Ceravolo, G.; Araniti, F.; Anastasi, U.; Sunseri, F. Morpho-agronomic and AFLP characterization to explore guar (Cyamopsis tetragonoloba L.) genotypes for the Mediterranean environment. Ind. Crop Prod. 2016, 86, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Yi, X.; Yang, H.; Zhou, H.; Yu, Y.; Tian, Y.; Lu, X. Genetic diversity evaluation of winged bean (Psophocarpus tetragonolobus (L.) DC.) using inter-simple sequence repeat (ISSR). Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2015, 62, 823–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinmani, E.N.; Wachira, F.N.; Kinyua, M.G. Molecular diversity of Kenyan lablab bean (Lablab purpureusL. Sweet) accessions using amplified fragment length polymorphism markers. Am. J. Plant Sci. 2012, 3, 3–32. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, J.; Chao, C.C.; Roberts, P.A.; Ehlers, J.D. Genetic diversity of cowpea [Vigna unguiculata (L.) Walp.] in four West African and USA breeding programs as determined by AFLP analysis. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2007, 54, 1197–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zannouou, A.; Kossou, D.K.; Ahanchede, A.; Zoundjihékpon, J.; Agbicodo, E.; Struik, P.C.; Sanni, A. Genetic variability of cultivated cowpea in Benin assessed by random amplified polymorphic DNA. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2008, 7, 24. [Google Scholar]

- Varshney, R.K.; Chen, W.; Li, Y.; Bharti, A.K.; Saxena, R.K.; Schlueter, J.A.; Donoghue, M.T.; Azam, S.; Fan, G.; Whaley, A.M.; et al. Draft genome sequence of pigeonpea (Cajanus cajan), an orphan legume crop of resource-poor farmers. Nat. Biotechnol. 2012, 30, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Palve, A.S.; Patel, S.K.; Selvanayagam, S.; Sharma, R.; Rathore, A. Development of genomic microsatellite markers in cluster bean using next-generation DNA sequencing and their utility in diversity analysis. Curr. Plant Biol. 2020, 21, 2214–6628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunkanmi, L.A.; Ogundipe, O.T.; Ng, N.Q.; Fatokun, C.A. Genetic diversity in wild relatives of cowpea (Vigna unguiculata) as revealed by simple sequence repeats (SSR) markers. J. Food Agric. Environ. 2008, 6, 253–268. [Google Scholar]

- Shivakumar, M.S.; Ramesh, S. Transferability of cross legume species/genera SSR markers to Dolichos Bean (Lablab purpureus L. Sweet) var. Lignosus. Ecialisesp 2015, 49, 263–265. [Google Scholar]

- Rai, N.; Kumar, S.; Singh, R.K.; Rai, K.K.; Tiwari, G.; Kashyap, S.P.; Singh, M.; Rai, A.B. Genetic diversity in Indian bean (Lablab purpureus) accessions as revealed by quantitative traits and cross-species transferable SSR markers. Indian J. Agric. Sci. 2016, 86, 654–660. [Google Scholar]

- Saxena, R.K.; Von Wettberg, E.; Upadhyaya, H.D.; Sanchez, V.; Songok, S.; Saxena, K.; Kimurto, P.; Varshney, R.K. Genetic diversity and demographic history of Cajanus spp. illustrated from genome-wide SNPs. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e88568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, O.; Randhawa, G.S. Identification and characterization of SSR, SNP and InDel molecular markers from RNA-Seq data of guar (Cyamopsis tetragonoloba, L. Taub.) roots. BMC Genom. 2018, 19, 951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatanparast, M.; Shetty, P.; Chopra, R.; Doyle, J.J.; Sathyanarayana, N.; Egan, A.N. Transcriptome sequencing and marker development in winged bean (Psophocarpus tetragonolobus; Leguminosae). Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 29070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venkatesha, S.C.; Ganapathy, K.N.; Gowda, M.B.; Gowda, P.R.; Mahadevu, P.; Girish, G.; Ajay, B.C. Variability and Genetic Structure among Lablab Bean Collections of India and their Relationship with Exotic Accessions. Vegetos 2013, 26, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muchero, W.; Diop, N.N.; Bhat, P.R.; Fenton, R.D.; Wanamaker, S.; Pottorff, M.; Hearne, S.; Cisse, N.; Fatokun, C.; Ehlers, J.D.; et al. A consensus genetic map of cowpea [Vigna unguiculata (L) Walp.] and synteny based on EST-derived SNPs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 18159–18164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohra, A.; Saxena, R.K.; Gnanesh, B.N.; Saxena, K.; Byregowda, M.; Rathore, A.; KaviKishor, P.B.; Cook, D.R.; Varshney, R.K. An intra-specific consensus genetic map of pigeonpea [Cajanus cajan (L.) Millspaugh] derived from six mapping populations. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2012, 125, 1325–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, S.; Mahato, A.K.; Singh, S.; Mandal, P.; Bhutani, S.; Dutta, S.; Kumawat, G.; Singh, B.P.; Chaudhary, A.K.; Yadav, R.; et al. A high-density intraspecific SNP linkage map of pigeonpea (Cajanascajan L. Millsp.). PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0179747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, R.K.; Singh, V.K.; Kale, S.M.; Tathineni, R.; Parupalli, S.; Kumar, V.; Garg, V.; Das, R.R.; Sharma, M.; Yamini, K.N.; et al. Construction of genotyping-by-sequencing based high-density genetic maps and QTL mapping for fusarium wilt resistance in pigeonpea. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, R.K.; Kale, S.M.; Kumar, V.; Parupali, S.; Joshi, S.; Singh, V.; Garg, V.; Das, R.R.; Sharma, M.; Yamini, K.N.; et al. Genotyping-by-sequencing of three mapping populations for identification of candidate genomic regions for resistance to sterility mosaic disease in pigeonpea. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naoumkina, M.; Torres-Jerez, I.; Allen, S.; He, J.; Zhao, P.X.; Dixon, R.A.; May, G.D. Analysis of cDNA libraries from developing seeds of guar (Cyamopsis tetragonoloba (L.) Taub). BMC Plant Biol. 2007, 7, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuravadi, A.N.; Tiwari, P.B.; Tanwar, U.K.; Tripathi, S.K.; Dhugga, K.S.; Gill, K.S.; Randhawa, G.S. Identification and characterization of EST-SSR markers in clusterbean (Cyamopsis spp.). Crop Sci. 2014, 54, 1097–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Parekh, M.J.; Patel, C.B.; Zala, H.N.; Sharma, R.; Kulkarni, K.S.; Fougat, R.S.; Bhatt, R.K.; Sakure, A.A. Development and validation of EST-derived SSR markers and diversity analysis in cluster bean (Cyamopsis tetragonoloba). J. Plant Biochem. Biot. 2015, 25, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, C.S.; Verma, S.; Singh, V.; Khan, S.; Gaur, P.; Gupta, P.; Nizar, M.A.; Dikshit, N.; Pattanayak, R.; Shukla, A.; et al. Characterization of winged bean (Psophocarpus tetragonolobus (L.) DC.) based on molecular, chemical and physiological parameter. Am. J. Mol. Biol. 2013, 3, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, M.A. Transcriptome sequencing and marker development for four underutilized legumes. Appl. Plant Sci. 2015, 3, 1400111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, Q.N.; Tanzi, A.S.; Ho, W.K.; Malla, S.; Blythe, M.; Karunaratne, A.; Massawe, F.; Mayes, S. Development of gene-based SSR markers in winged bean (Psophocarpus tetragonolobus (L.) DC.) for diversity assessment. Genes 2017, 8, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konduri, V.; Godwin, I.D.; Liu, C.J. Genetic mapping of the Lablab purpureus genome suggests the presence of “cuckoo” gene(s) in this species. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2000, 100, 866–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.M.; Zhang, L.D.; Hu, Y.L.; Wang, B.; Wu, T.L. Characterization of novel soybean derived simple sequence repeat markers and their transferability in hyacinth bean [Lablab purpureus (L.) Sweet]. Indian J. Genet. Plant Breed. 2012, 72, 46. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesha, S.C.; Byregowda, M.; Mahadevu, P.; Mohan Rao, A.; Kim, D.J.; Ellis, T.H.N.; Knox, M.R. Genetic diversity within Lablab purpureus and the transferability of gene-specific markers from a range of legume species. Plant Genet. Resou. 2007, 5, 154–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramtekey, V.; Bhuriya, A.; Ayer, D.; Parekh, V.; Modha, K.; Kale, B.; Vadodariya, G.; Patel, R. Molecular tagging of photoperiod responsive flowering in Indian bean [Lablab purpureus (L.) Sweet]. Indian J. Genet. 2019, 79, 269. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G.; Xu, S.; Mao, W.; Gong, Y.; Hu, Q. Development of EST-SSR markers to study genetic diversity in hyacinth bean (Lablab purpureus L.). Plant Omics 2013, 6, 295–301. [Google Scholar]

- Vaijayanthi, P.V.; Ramesh, S.; Gowda, M.B.; Rao, A.M.; Keerthi, C.M. Genome-wide marker-trait association analysis in a core set of Dolichos bean germplasm. Plant Genet. Res. 2018, 17, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Wu, X.; Wang, B.; Liu, Y.; Ehlers, J.D.; Close, T.J.; Roberts, P.A.; Diop, N.N.; Qin, D.; Hu, T.; et al. A SNP and SSR based genetic map of asparagus bean (Vigna. unguiculata ssp. sesquipedialis) and comparison with the broader species. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e15952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kongjaimun, A.; Somta, P.; Tomooka, N.; Kaga, A.; Vaughan, D.A.; Srinives, P. QTL mapping of pod tenderness and total soluble solid in yardlong bean [Vigna unguiculata (L.) Walp. subsp.unguiculatacv.-gr. sesquipedalis]. Euphytica 2013, 189, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Wu, X.; Wang, B.; Hu, T.; Lu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Qin, D.; Wang, S.; Li, G. QTL mapping and epistatic interaction analysis in asparagus bean for several characterized and novel horticulturally important traits. BMC Genet. 2013, 14, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnanesh, B.N.; Bohra, A.; Sharma, M.; Byregowda, M.; Pande, S.; Wesley, V.; Saxena, R.K.; Saxena, K.B.; Kishor, P.K.; Varshney, R.K. Genetic mapping and quantitative trait locus analysis of resistance to sterility mosaic disease in pigeonpea [Cajanus cajan (L.) Millsp.]. Field Crops. Res. 2011, 123, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumawat, G.; Raje, R.S.; Bhutani, S.; Pal, J.K.; Mithra, A.S.; Gaikwad, K.; Sharma, T.R.; Singh, N.K. Molecular mapping of QTLs for plant type and earliness traits in pigeonpea (Cajanus cajan L. Millsp.). BMC Genet. 2012, 13, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mir, R.R.; Kudapa, H.; Srikanth, S.; Saxena, R.K.; Sharma, A.; Azam, S.; Saxena, K.; Penmetsa, R.V.; Varshney, R.K. Candidate gene analysis for determinacy in pigeonpea (Cajanus spp.). Theor. Appl. Genet. 2014, 127, 2663–2678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, V.K.; Khan, A.W.; Saxena, R.K.; Kumar, V.; Kale, S.M.; Sinha, P.; Chitikineni, A.; Pazhamala, L.T.; Garg, V.; Sharma, M.; et al. Next-generation sequencing for identification of candidate genes for Fusarium wilt and sterility mosaic disease in pigeonpea (Cajanus cajan). Plant Biotechnol. J. 2016, 14, 1183–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohra, A.; Jha, R.; Pandey, G.; Patilm, P.G.; Saxena, R.K.; Singh, I.P.; Singh, D.; Mishra, R.K.; Mishra, A.; Singh, F.; et al. New hypervariable ssr markers for diversity analysis, hybrid purity testing and trait mapping in pigeonpea [Cajanus cajan (L.) Millspaugh]. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, R.K.; Obala, J.; Sinjushin, A.; Kumar, C.S.; Saxena, K.B.; Varshney, R.K. Characterization and mapping of Dt1 locus which co-segregates with CcTFL1 for growth habit in pigeonpea. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2017, 130, 1773–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, R.K.; Kale, S.; Mir, R.R.; Mallikarjuna, N.; Yadav, P.; Das, R.R.; Molla, J.; Sonnappa, M.; Ghanta, A.; Narasimhan, Y.; et al. Genotyping-by-sequencing and multilocation evaluation of two interspecific backcross populations identify QTLs for yield-related traits in pigeonpea. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2020, 133, 737–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajaj, A. Molecular Mapping of Bacterial Blight Resistance Gene, Drought Tolerant QTL (s) and Genetic Diversity Analysis in Clusterbean {Cyamopsis Tetragonoloba (L) Taub}. Ph.D. Thesis, Chaudhary Charan Singh Haryana Agricultural University, Hisar, India, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, P.; Kumar, V.; Raman, K.; Tiwari, K. A set of SCAR markers in cluster bean (Cyamopsis tetragonoloba L. Taub) genotypes. Adv. Bio. Biotechnol. 2014, 5, 131–141. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, J.; Yang, R.; Wu, T. Bayesian mapping QTL for fruit and growth phenological traits in Lablab purpureus (L.) Sweet. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2009, 8, 167–175. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, J.; Wang, B.; Wu, T.L. Quantitative trait loci (QTL) mapping for inflorescence length traits in Lablab purpureus (L.) sweet. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2011, 10, 3558–3566. [Google Scholar]

- Shivachi, A.; Kiplagat, K.O.; Kinyua, G.M. Microsatellite analysis of selected Lablab purpureus genotypes in Kenya. Rwanda J. 2012, 28, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanktesha, C. Molecular Characterization and Development of Mapping Populations for Construction of Genetic Map in Dolichos Bean [Lablab Purpureus L. (sweet)]. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Agricultural Sciences, Banglore, India, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, P.; Moshelion, M.; Wu, X.; Halperin, O.; Wang, B.; Luo, J.; Wallach, R.; Wu, X.; Lu, Z.; Li, G. Natural variation and gene regulatory basis for the responses of asparagus beans to soil drought. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Wu, X.; Xu, P.; Wang, B.; Lu, Z.; Li, G. Association mapping for fusarium wilt resistance in chinese asparagus bean germplasm. Plant Genome 2015, 8, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suanum, W.; Somta, P.; Kongjaimun, A.; Yimram, T.; Kaga, A.; Tomooka, N.; Takahashi, Y.; Srinives, P. Co-localization of QTLs for pod fiber content and pod shattering in F2 and backcross populations between yard long bean and wild cowpea. Mol. Breed. 2016, 36, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Wu, X.; Muñoz-Amatriaín, M.; Wang, B.; Wu, X.; Hu, Y.; Huynh, B.L.; Close, T.J.; Roberts, P.A.; Zhou, W.; et al. Genomic regions, cellular components and gene regulatory basis underlying pod length variations in cowpea (V. unguiculata L. Walp). Plant Biotechnol. J. 2017, 15, 547–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Wang, N.; Wu, Z.; Guo, R.; Yu, X.; Zheng, Y.; Xia, Q.; Gui, S.; Chen, C. A high density genetic map derived from rad sequencing and its application in qtl analysis of yield-related traits in Vigna unguiculata. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Tan, H.; Xu, D.; Tang, Y.; Niu, Y.; Lai, Y.; Tie, M.; Li, H. High-density genetic map construction and comparative genome analysis in asparagus bean. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Li, G.; Wang, B.; Hu, Y.; Wu, X.; Wang, Y.; Lu, Z.; Xu, P. Fine mapping Ruv2, a new rust resistance gene in cowpea (Vigna unguiculata), to a 193-kb region enriched with NBS-type genes. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2018, 131, 2709–2718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watcharatpong, P.; Kaga, A.; Chen, X.; Somta, P. Narrowing down a major QTL region conferring pod fiber contents in yardlong bean (Vigna unguiculata), a vegetable cowpea. Genes 2020, 11, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmutz, J.; Cannon, S.B.; Schlueter, J.; Ma, J.; Mitros, T.; Nelson, W.; Hyten, D.L.; Song, Q.; Thelen, J.J.; Cheng, J.; et al. Genome sequence of the palaeopolyploid soybean. Nature 2010, 463, 178–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cannon, S.B.; May, G.D.; Jackson, S.A. Three sequenced legume genomes and many crop species: Rich opportunities for translational genomics. Plant Physiol. 2009, 151, 970–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, N.K.; Gupta, D.K.; Jayaswal, P.K.; Mahato, A.K.; Dutta, S.; Singh, S.; Bhutani, S.; Dogra, V.; Singh, B.P.; Kumawat, G.; et al. The first draft of the pigeonpea genome sequence. J. Plant Biochem. Biotechnol. 2012, 21, 98–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Liu, H.; Liu, M.; Liao, X.; Sahu, S.K.; Fu, Y.; Song, B.; Cheng, S.; Kariba, R.; Muthemba, S.; et al. The draft genomes of five agriculturally important African orphan crops. GigaScience 2019, 8, giy152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Q.; Pan, L.; Zhang, R.; Ni, X.; Wang, Y.; Dong, X.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Kui, L.; Li, Y.; et al. The genome assembly of asparagus bean, Vigna unguiculata ssp. sesquipedialis. Sci. Data 2019, 6, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronk, Q.; Ojeda, I.; Pennigton, R.T. Legume comparative genomics: Progress in phylogenetics and phylogenomics. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2009, 9, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zuelsdorf, C.; Penneys, D.; Fan, S.; Kofsky, J.; Song, B.H. Transcriptome profiling of a beach-adapted wild legume for dissecting novel mechanisms of salinity tolerance. Sci. Data 2018, 5, 180290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Feng, Q.; Qian, Q.; Zhao, Q.; Wang, L.; Wang, A.; Guan, J.; Fan, D.; Weng, Q.; Huang, T. High-throughput genotyping by whole-genome resequencing. Genome Res. 2009, 19, 1068–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baird, N.A.; Etter, P.D.; Atwood, T.S.; Currey, M.C.; Shiver, A.L.; Lewis, Z.A.; Selker, E.U.; Cresko, W.A.; Johnson, E.A. Rapid SNP discovery and genetic mapping using sequenced RAD markers. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e3376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, R.K.; Patel, K.; Kumar, C.S.; Tyagi, K.; Saxena, K.B.; Varshney, R.K. Molecular mapping and inheritance of restoration of fertility (Rf) in A4 hybrid system in pigeonpea (Cajanus cajan (L.) Millsp.). Theor. Appl. Genet. 2018, 131, 1605–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hart, J.P.; Griffiths, P.D. Genotyping-by-sequencing enabled mapping and marker development for the by-2 potyvirus resistance allele in common bean. Plant Genome 2015, 8, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, J.; Shi, A.; Mou, B.; Bhattarai, G.; Yang, W.; Weng, Y.; Motes, D. Association mapping of aphid resistance in USDA cowpea (Vigna unguiculata L. Walp.) core collection using SNPs. Euphytica 2017, 213, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, M.J. High-throughput SNP genotyping to accelerate crop improvement. Plant Breed. Biotechnol. 2014, 2, 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, S.; Zhang, W.; Akhunov, E.; Sherman, J.; Ma, Y.; Luo, M.C.; Dubcovsky, J. Analysis of gene-derived SNP marker polymorphism in US wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) cultivars. Mol. Breed. 2009, 23, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, P.; Saxena, K.B.; Hingane, A.; Kumar, C.S.; Kandalkar, V.S.; Varshney, R.K.; Saxena, R.K. An “Axiom Cajanus SNP Array” based high density genetic map and QTL mapping for high-selfing flower and seed quality traits in pigeonpea. BMC Genom. 2019, 20, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Mellor, K.E.; Paul, S.N.; Lawson, M.J.; Mackey, A.J.; Timko, M.P. Global changes in gene expression during compatible and incompatible interactions of cowpea (Vigna unguiculata L.) with the root parasitic angiosperm Striga gesnerioides. BMC Genom. 2012, 13, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Mahato, A.K.; Jayaswal, P.K.; Singh, N.; Dheer, M.; Goel, P.; Raje, R.S.; Yasin, J.K.; Sreevathsa, R.; Rai, V.; et al. A 62K genic-SNP chip array for genetic studies and breeding applications in pigeonpea (Cajanus cajan L. Millsp.). Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, A.N.; Farmer, A.N.; Schlueter, J.E.; Cannon, S.B.; Abernathy, B.R.; Tuteja, R.E.; Woodward, J.I.; Shah, T.R.; Mulasmanovic, B.E.; Kudapa, H.I.; et al. Defining the transcriptome assembly and its use for genome dynamics and transcriptome profiling studies in pigeonpea (Cajanus cajan L.). DNA Res. 2011, 18, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, S.; Kumawat, G.; Singh, B.P.; Gupta, D.K.; Singh, S.; Dogra, V.; Gaikwad, K.; Sharma, T.R.; Raje, R.S.; Bandhopadhya, T.K.; et al. Development of genic-SSR markers by deep transcriptome sequencing in pigeonpea [Cajanus cajan (L.) Millspaugh]. BMC Plant Biol. 2011, 11, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazhamala, L.T.; Purohit, S.; Saxena, R.K.; Garg, V.; Krishnamurthy, L.; Verdier, R.; Varshney, R.K. Gene expression atlas of pigeonpea and its application to gain insights into genes associated with pollen fertility implicated in seed formation. J. Exp. Bot. 2017, 68, 2037–2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rathinam, M.; Mishra, P.; Vasudevan, M.; Budhwar, R.; Mahato, A.; Prabha, A.L.; Singh, N.K.; Rao, U.; Sreevathsa, R. Comparative transcriptome analysis of pigeonpea, Cajanus cajan (L.) and one of its wild relatives Cajanus platycarpus(Benth.) Maesen. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0218731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.; Singh, P.K.; Sharma, A.K.; Singh, N.K.; Sonah, H.; Deshmukh, R.; Sharma, T.R. Understanding the role of the WRKY gene family under stress conditions in pigeonpea (Cajanus Cajan L.). Plants 2019, 8, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saxena, R.K.; Rathore, A.; Bohra, A.; Yadav, P.; Das, R.R.; Khan, A.W.; Singh, V.K.; Chitikineni, A.; Singh, I.P.; Kumar, C.S.; et al. Development and application of high-density Axiom Cajanus SNP array with 56K SNPs to understand the genome architecture of released cultivars and founder genotypes. Plant Genome 2018, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanwar, U.K.; Pruthi, V.; Randhawa, G.S. RNA-seq of guar (Cyamopsis tetragonoloba, l. taub.) leaves: De novo transcriptome assembly, functional annotation and development of genomic resources. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rawal, H.C.; Kumar, S.; Mithra, S.V.; Solanke, A.U.; Nigam, D.; Saxena, S.; Tyagi, A.; Yadav, N.R.; Kalia, P.; Singh, N.P.; et al. High quality unigenes and microsatellite markers from tissue specific transcriptome and development of a database in clusterbean (Cyamopsis tetragonoloba, L. Taub). Genes 2017, 8, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahu, S.; Rao, A.R.; Pandey, J.; Gaikwad, K.; Ghoshal, S.; Mohapatra, T. Genome-wide identification and characterization of lncRNAs and miRNAs in cluster bean (Cyamopsis tetragonoloba). Gene 2018, 667, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tribhuvan, K.U.; Mithra, S.V.A.; Sharma, P.; Das, A.; Kumar, K.; Tyagi, A.; Solanke, A.U.; Sharma, R.; Jadhav, P.V.; Raveendran, M.; et al. Identification of genomic SSRs in cluster bean (Cyamopsis tetragonoloba) and demonstration of their utility in genetic diversity analysis. Ind. Crops Prod. 2019, 133, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigoreva, E.; Ulianich, P.; Ben, C.; Gentzbittel, L.; Potokina, E. First Insights into the Guar (Cyamopsis tetragonoloba (L.) Taub.) Genome of the ‘Vavilovskij 130’Accession, Using Second and Third-Generation Sequencing Technologies. Rus. J. Genet. 2019, 55, 1406–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.; Goel, R.; Pande, V.; Asif, M.H.; Mohanty, C.S. De novo sequencing and comparative analysis of leaf transcriptomes of diverse condensed tannin-containing lines of underutilized Psophocarpus tetragonolobus (L.) DC. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 44733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yssel, E.J.; Kao, S.; Peer, Y.V.; Sterck, L. ORCAE-AOCC: A centralized portal for the annotation of african orphan crop genomes. Genes 2019, 10, 950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, H.; Huang, H.; Tie, M.; Tang, Y.; Lai, Y.; Li, H. Transcriptome profiling of two asparagus bean (Vigna Unguiculata subsp. sesquipedalis) cultivars differing in chilling tolerance under cold stress. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0151105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuo, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, B.; Luo, Y.; Wang, Q.; Gao, L. sRNAome and transcriptome analysis provide insight into chilling response of cowpea pods. Gene 2018, 671, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spriggs, A.; Henderson, S.T.; Hand, M.L.; Johnson, S.D.; Taylor, J.M.; Koltunow, A. Assembled genomic and tissue-specific transcriptomic data resources for two genetically distinct lines of Cowpea (Vigna unguiculata (L.) Walp). Gates Open Res. 2018, 2, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Amatriaín, M.; Mirebrahim, H.; Xu, P.; Wanamaker, S.I.; Luo, M.; Alhakami, H.; Alpert, M.; Atokple, I.; Batieno, B.J.; Boukar, O.; et al. Genome resources for climate-resilient cowpea, an essential crop for food security. Plant J. 2017, 89, 1042–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K.K.; Lavanya, M.; Anjaiah, V. Agrobacterium mediated production of transgenic (Cajanus cajan L. Millsp.) expressing the synthetic BT cry1Ab gene. Vitr. Cell. Dev. Bio. Plant 2006, 42, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eapen, S. Advances in development of transgenic pulse crops. Biotechnol. Adv. 2008, 26, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dita, M.A.; Rispail, N.; Prats, E.; Rubiales, D.; Singh, K.B. Biotechnology approaches to overcome biotic and abiotic stress constraints in legumes. Euphytica 2006, 147, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamurthy, K.V.; Suhasini, K.; Sagare, A.P.; Meixner, M.; De Kathen, A.; Pickardt, T.; Schieder, O. Agrobacterium mediated transformation of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) embryo axes. Plant Cell Rep. 2000, 19, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.M.; Kumar, B.K.; Sharma, K.K.; Devi, P. Genetic transformation of pigeonpea with rice chitinase gene. Plant Breed. 2004, 123, 485–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakshi, S.; Roy, N.K.; Sahoo, L. Seedling preconditioning in thidiazuron enhances axillary shoot proliferation and recovery of transgenic cowpea plants. PCTOC 2012, 110, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thu, T.T.; Dewaele, E.; Trung, L.Q.; Claeys, M.; Jacobs, M.; Angenon, G. Increasing lysine levels in pigeonpea (Cajanus cajan (L.) Millsp.) seeds through genetic engineering. PCTOC 2007, 91, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surekhs, C.; Kumari, N.K.; Aruna, V.; Suneetha, G.; Arundhati, A.; Kishor, P.B. Expression of the Vigna aconitifolia P5CSF129A gene in transgenic pigeonpea enhances proline accumulation and salt tolerance. Plant Cell Rep. 2014, 116, 27–36. [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan, S.G.; Dwivedi, N.K.; Singh, J.P. Primitive weedy forms of guar, adak guar: Possible missing link in the domestication of guar [Cyamopsis tetragonoloba (L.) Taub.]. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2011, 58, 961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramu, S.V.; Rohini, S.; Keshavareddy, G.; Gowri Neelima, M.; Shanmugam, N.B.; Kumar, A.R.V.; Sarangi, S.K.; Ananda Kumar, P.; Udayakumar, M. Expression of a synthetic cry1AcF gene in transgenic Pigeon pea confers resistance to Helicoverpa armigera. J. Appl. Entomol. 2012, 136, 675–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshamma, E.; Sreevathsa, R.; Kumar, A.M.; Reddy, K.N.; Manjulatha, M.; Shanmugam, N.B.; Kumar, A.R.; Udayakumar, M. Agrobacterium-mediated in planta transformation of field bean (Lablab purpureus L.) and recovery of stable transgenic plants expressing the cry1AcF gene. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 2012, 30, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solleti, S.K.; Bakshi, S.; Purkayastha, J.; Panda, S.K.; Sahoo, L. Transgenic cowpea (Vigna unguiculata) seeds expressing a bean α-amylase inhibitor 1 confers resistance to storage pests, bruchid beetles. Plant Cell Rep. 2008, 27, 1841–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adesoye, A.; Machuka, J.; Togun, A. CRY 1AB transgenic cowpea obtained by nodal electroporation. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2008, 7, 3200–3210. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, N.; Murphy, J.B. Enhanced isoflavone biosynthesis in transgenic cowpea (Vigna unguiculata l.) Callus. Plant Mol. Biol. Biotechnol. 2012, 3, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Klu, G.Y.P.; Raemakers, C.J.J.M.; Jacobsen, E.; Van-Harten, A.M. Direct organogenesis and somatic embryogenesis in mature cotyledon explants of winged bean (Psophocarpus tetragonolobus (L.) DC) using cytokinin-based media. Plant Genet. Res. Newsl. 2002, 2002, 51–69. [Google Scholar]

- Venketeswaran, S.; Dias, M.A.D.L.; Weyers, U.V. Organogenesis and somatic embryogenesis from callus of winged bean (Psophocarpus tetragonolobus (L.) DC.). Acta Hortic. 1990, 280, 202–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.; Chauhan, N.S.; Singh, M.; Idris, A.; Madanala, R.; Pande, V.; Mohanty, C.S. Establishment of an efficient and rapid method of multiple shoot regeneration and a comparative phenolics profile in in vitro and greenhouse-grown plants of Psophocarpus tetragonolobus (L.) DC. Plant Signal. Behav. 2014, 9, e970443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, V.M.; Haq, N.; Evans, P.K. Protoplast isolation, culture and plant regeneration in the winged bean, Psophocarpus tetragonolobus (L) DC. Plant Sci. 1985, 41, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, W.A.; Dedhrotiya, A.T.; Khan, N.; Gargi, T.; Patel, J.B.; Acharya, S. An efficient in vitro regeneration protocol from cotyledon and cotyledonary node of cluster bean (Cyamopsis tetragonoloba L Taub). Curr. Tren. Biotechnol. Pharm. 2015, 9, 175–181. [Google Scholar]

- Meghwal, M.K.; Kalaskar, S.R.; Rathod, A.H.; Tikka, S.B.S.; Acharya, S. Effect of plant growth regulators on in vitro regeneration from different explants in cluster bean [Cyamopsis tetragonoloba (L.) Taub]. J. Cell Tissu. Res. 2014, 14, 4647–4652. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, D.; Xue, Q.; McElroy, D.; Mawal, Y.; Hilder, V.A.; Wu, R. Constitutive expression of a cowpea trypsin inhibitor gene, CpTi, in transgenic rice plants confers resistance to two major rice insect pests. Mol. Breed. 1996, 2, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.S.; Xiong, L.; Jing, Y.; Liu, B. Lysine Rich Protein from Winged Bean. U.S. Patent No. 6184437, 6 February 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, C.; Chen, X.; Liang, R.; Yang, F.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, X.; Chen, T.; Sun, S.S. Expression of lysine-rich protein gene and analysis of lysine content in transgenic wheat. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2004, 49, 2053–2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R.C.; Doudna, J.A. Molecular mechanisms of RNA interference. Ann. Rev. Biophys. 2013, 42, 217–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prins, M.; Laimer, M.; Noris, E.; Schubert, J.; Wassenegger, M.; Tepfer, M. Strategies for antiviral resistance in transgenic plants. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2008, 9, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, R.P.; Raman, V.; Dhandapani, G.; Malhotra, E.V.; Sreevathsa, R.; Kumar, P.A.; Sharma, T.R.; Pattanayak, D. Silencing of HaAce1 gene by host-delivered artificial microRNA disrupts growth and development of Helicoverpaarmigera. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0194150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, K.H.; Waterhouse, P.M. RNAi for insect-proof plants. Nature Biotechnol. 2007, 25, 1231–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devos, Y.; Maeseele, P.; Reheul, D.; Van Speybroeck, L.; De Waele, D. Ethics in the Societal Debate on Genetically Modified Organisms: A (Re)Quest for Sense and Sensibility. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2007, 21, 29–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walt, E. Gene edited CRISPER mushroom escapes US regulation. Nature 2016, 532, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen-Tannoudji, M.; Robine, S.; Choulika, A.; Pinto, D.; El Marjou, F.; Babinet, C.; Louvard, D.; Jaisser, F. I-SceI-induced gene replacement at a natural locus in embryonic stem cells. Mol. Cellu. Biol. 1998, 18, 1444–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibikova, M.; Golic, M.; Golic, K.G.; Carroll, D. Targeted chromosomal cleavage and mutagenesis in Drosophila using zinc finger nucleases. Genetics 2002, 161, 1169–1175. [Google Scholar]

- Christian, M.; Cermak, T.; Doyle, E.L.; Schmidt, C.; Zhang, F.; Hummel, A.; Bogdanove, A.J.; Voytas, D.F. Targeting DNA double-strand breaks with TAL effector nucleases. Genetics 2010, 186, 757–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mali, P.; Yang, L.; Esvelt, K.M.; Aach, J.; Guell, M.; DiCarlo, J.E.; Norville, J.E.; Church, G.M. RNA-guided human genome engineering via Cas9. Science 2013, 339, 823–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, N.M.; Baltes, N.J.; Voytas, D.F.; Douches, D.S. Geminivirus-mediated genome editing in potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) using sequence-specific nucleases. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, G.; Jia, M.; Chen, K.; Kong, X.; Khattak, B.; Xie, C.; Li, A.; Mao, L. CRISPR/Cas9: A powerful tool for crop genome editing. Crop J. 2016, 4, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Z.; Eid, A.; Ali, S.; Mahfouz, M.M. Pea early-browning virus -mediated genome editing via the CRISPR/Cas9 system in Nicotiana benthamiana and Arabidopsis. Virus Res. 2018, 244, 333–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Massel, K.; Godwin, I.D.; Gao, C. Applications and potential of genome editing in crop improvement. Genome Biol. 2018, 19, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maphosa, Y.; Jideani, V.A. The role of legumes in human nutrition. Funct. Food Improv. Health Adequate Food. 2017, 2, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Ruelle, M.L.; Asfaw, Z.; Dejen, A.; Tewolde-Berhan, S.; Nebiyu, A.; Tana, T.; Power, A.G. Inter-and intraspecific diversity of food legumes among households and communities in Ethiopia. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0227074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAO; IFAD; UNICEF; WFP; WHO. State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2019. Safeguarding Against Economic Slowdowns and Downturns. 2019. Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/ca5162en/ca5162en (accessed on 10 June 2020).

- Botelho, R.; Araújo, W.; Pineli, L. Food formulation and not processing level: Conceptual divergences between public health and food science and technology sectors. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 58, 639–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Crop | Molecular Marker/QTL | Source | Trait/Objective | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pigeon pea | qSMD4 major QTL and minor QTLs | F2 (ICP 8863 × ICPL 20097 TTB 7 × ICP 7035) | Sterility mosaic resistance | [87] |

| 13 QTLs for six traits | (Pusa Dwarf × HDM04-1) | Earliness, plant type, high-density linkage map | [88] | |

| 339 SSR, 4 QTLs | F2 (ICPB 2049 × ICPL 99050, ICPA 2043 × ICPR 3467, ICPA 2039 × ICPR 2447, ICPA 2043 × ICPR 2671) | Linkage map, fertility restoration | [68] | |

| CcTFL1 gene | F2 (ICPL 85010 × ICP 15774) | Determinacy | [89] | |

| C.cajan_01839 for sterility mosaic, C. cajan_03203 for Fusarium wilt | RILs (ICPL 20096 × ICPL 332) | Fusarium wilt, sterility mosaic disease | [90] | |

| 421 hypervariable SSRs from a genome sequence | 94 genotypes | Diversity Analysis, Hybrid Purity Testing, Trait Mapping | [91] | |

| 3 major QTLs (CcLG11) | F2, RIL (ICPL 20096 × ICPL 332, ICPL 20097 × ICP 8863, ICP 8863 × ICPL 87119) | Sterility mosaic resistance | [71] | |

| Dt1 locus, Indel marker fromCcTFL1 gene | F2 (ICP 5529 × ICP 11605) | Determinacy | [92] | |

| 547 SNP (bead-array), 319 SNP (RAD), 65 SSR | F2 (Asha × UPAS, Pusa Dwarf × H2001-4, Pusa Dwarf × HDM04-1) | Molecular linkage map | [69] | |

| CcLG08 carry major QTL | F2 (ICPA 2039 × ICPL 87119 | Fertility restoration | [92] | |

| CcLG07 (8 QTLs), SNP S7_14185076 (linked to 4 traits) | BC (ICPL 87119 × ICPW 15613, ICPL 87119 × ICPW 29) | Yield related traits | [93] | |

| Cluster bean | 16,476 EST | HES 1401 | cDNA library from seeds | [72] |

| L19, D1, AB7 and QLTY 3 (Bacterial blight) and OPQ 20,OPD10, OPD14,OPQ 12,OPAC 8 and OPF 9 (drought tolerance) QTLs | HG 75 × PNB (Bacterial blight) and HG 563 × PNB (drought tolerance) | Mapping Bacterial blight resistance and drought tolerance | [94] | |

| 5 RAPD | 35 genotypes | RAPD and ISSR cloning and sequencing | [95] | |

| 100 SSRs | 32 genotypes | Validation of SSRs | [74] | |

| 15,399 SSRs | GG-4 variety | Sequencing by Miseq NGS | [59] | |

| Winged bean | 13 RAPD and 7 ISSR | 24 accessions | Molecular characterization | [75] |

| 100 ISSR | 45 accessions | Diversity analysis | [54] | |

| 1900 SSRs | Ibadan Local-1 | Transcriptome sequencing -Illumina HiSeq 2500 | [76] | |

| 12,956 SSRs, 5190 SNPs | 2 accessions | Transcriptome sequencing- Roche 454 Genome Sequencer FLX | [65] | |

| 9682 SSR | 6 accessions | Transcriptome sequencing-Illumina MiSeq | [77] | |

| 20 SSRs | 53 accessions | Primer design from in house assembled transcriptome using primer3 | [33] | |

| Dolichos bean | 127 RFLP, 91 RAPD | Rongai (cultivar) × CPI 24973 (wild) -17 linkage groups, 1610 cM | F2 population for genetic linkage map | [78] |

| 41 main effect QTLs (22 for growth phenological traits and 19 for fruit traits) | Meidou2012 × ‘Nanhui23 | Growth phenological and fruit traits | [96] | |

| 40 QTLs (8.1 to 55.0% variation) | (Meidou2012 × Nanhui 23). | Inflorescence length traits | [97] | |

| 21 SSR | 13 genotypes | Transferability of SSRs from French bean/diversity analysis | [98] | |

| 60 SNPs, 16 InDels. | Sequencing polymorphic genic segments of 9 parents | Allele-specific PCR primers | [99] | |

| 22 SSRs | 420 unigenes | 479 EST from NCBI for SSR mining | [82] | |

| 42 SSRs | Transferability of markers from soybean, Medicago truncatula, green gram chickpea | [61] | ||

| 134 SSRs | 143 genotypes | Transferability of SSRs from French bean, mung bean, cowpea, faba bean, and moth bean/diversity analysis | [62] | |

| 9 QTLs using 234 SSRs | 64 accessions for GWAS | Fresh pod yield mapping | [83] | |

| PvTFLy1 locus | GNIB21 × GP189 | Photoperiod responsive flowering | [81] | |

| Cowpea/Asparagus bean | 191 SNP and 184 SSR loci | RILs (ZN016 × Zhijiang282) | Molecular linkage map | [84] |

| 3 QTLs for pod tenderness, 2 QTLs for total soluble solid | F2 and BC (P81610 × JP89083) | Pod tenderness and total soluble solid | [85] | |

| Major QTLs on LG 11 | RILs (ZN016 × ZJ282) | Days to first flowering (FLD), leaf senescence (LS), nodes to first flower (NFF), and pod number per plant (PN) | [86] | |

| 39 SNPs using GWAS | 95 accessions of asparagus bean | Drought tolerance | [100] | |

| 18 SNPs using GWAS | 95 asparagus bean, 4 African cowpea accessions | Fusarium wilt | [101] | |

| QTLS on LG 1,4,7 | F2 and BC (JP81610 × TVnu-457) | Pod fiber content and pod shattering | [102] | |

| 72 SNPs using GWAS | RILs (ZN016 × Zhijiang282) | Pod length | [103] | |

| 17,996 SNPs using RAD sequencing, QTLS on LG4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 11 | F2:3 (Green pod cowpea × Xiabao II) | High-density SNP map and yield traits | [104] | |

| 5225 SNP markers by SLAR-seq | F2 (Dubai bean × Ningjiang 3) | High-density map by sequencing | [105] | |

| Ruv2 locus | F2 and RILs (ZN016 × Zhijiang282) | Rust resistance | [106] | |

| qCel7.1, qHem7.1, and qLig7.1 | F2 (JP81610 × TVnu-457) | Pod fiber content | [107] |

| Crop | Objective | Description | Genetic Improvement of Vegetable Type | Platform | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pigeon pea | Transcriptome seq | 50,566 SSRs, 12,000 SNPs, 0.12 million unique sequences and 150.8 million sequence reads | Enhancing genomic resources | Roche FLX/454 | [125] |

| RNA-seq | 1.696 million reads, 3771 SSRs | To target protein-coding and regulatory genes | Roche 454 GS-FLX | [126] | |

| Gene expression atlas (CcGEA) | 590.84 million paired-end data from RNA-Seq, 28 793 genes, regulatory genes, i.e., pollen-specific (SF3), sucrose–proton symporter | To target protein-coding and regulatory genes | Illumina HiSeq 2000 | [127] | |

| Comparative transcriptome | Cajanus cajan (L.) and Cajanus platycarpus (Benth.) sequence revealed 0.11 million transcripts, 82% annotated | Valuable data from wild sources | Illumina Hi-Seq 2500 | [128] | |

| WRKY characterization | 94 WRKY genes characterized and validated phylogenetically three groups (I, II, III) | Elucidating stress-responsive machinery | qRT-PCR | [129] | |

| Axiom SNP array | 56K SNPs from 104 genotypes | SNP genotyping | Axiom Affymetrix | [130] | |

| CcSNPnkssnp chip for Affymetrix GeneTitan | 62k SNPs from conserved, unique, and stress resistance genes | SNP typing | Illumina Hiseq | [124] | |

| Cluster bean | seedling (Ibadan Local-1) | 1900 SSRs and 1800 conserved orthologous loci | Stimulating genomics accelerated breeding in winged bean | Illumina HiSeq 2500 | [76] |

| RNA-Seq | 5773 SSR, 3594 SNPs, 62,146 unigenes with mean 679 bp length, and 11,000 genes annotated for biochemical pathways | To target protein-coding and regulatory genes | Illumina HiSeq 2500 | [131] | |

| RNA-Seq | 127,706 transcripts, 48,007 non-redundant unigenes, 79% annotations,8687 SSRs | To target protein coding and regulatory genes | Illumina paired end sequencing | [132] | |

| CbLncRNAdb database | lncRNAs, miRNAs identification, and characterization | Understanding the stress mechanism | http://cabgrid.res.in/cblncrnadb. | [133] | |

| Whole-genome sequencing | 1859 SSRs from 1091 scaffolds constituting 60% genome of the cluster bean | Towards complete genome assembly | Illumina and Oxford nanopore | [134] | |

| Whole-genome assembly | 1.2 Gb genomic reads comprising 50% genome of cluster bean (Illumina and Oxford nanopore) | Towards complete genome assembly | Illumina HiSeq 2500 | [135] | |

| Genome sequencing of GG-4 | 15,399 SSRs generated | Towards complete genome assembly | Illumina MiSeq | [59] | |

| Winged bean | CPP34 (PI 491423) and CPP37 (PI 639033) accessions | 16,115 total contigs, 12,956 SSRs and 5190 SNPs developed | To target protein-coding and regulatory genes | Roche 454 Genome Sequencer FLX | [65] |

| Tissue specific (leaf, pod root, and reproductive tissues) | 198,554 contigs, 24,598 SSR motifs detected | Library of various tissues available for digging important traits | Illumina MiSeq | [77] | |

| Tannin controlling genes | 1235 contigs expressed differentially | Identification of candidates | Illumina Nextseq 500 | [136] | |

| Dolichos bean | ORCAE-AOCC | Genomic portal for orphan crops such as dolichos bean | Information for molecular studies | [137] | |

| Cowpea | Chilling tolerance | ICE1-CBF3-COR id cold-responsive cascade present in asparagus bean | Engineering cold-tolerant genotypes | Illumina Hiseq2500 | [138] |

| Molecular mechanism of chilling injury | Redox reactions enzymes, energy metabolism enzymes, and transcription factors, i.e., WRKY, MYB, bHLH, NAC, and ERF are involved in chilling injury | To plan genetic improvement by an understanding mechanism of chilling injury | Illumina HiSeq2500 | [139] | |

| Transformable cowpea genotypes | Tissue-specific data special emphasis on reproductive organs | Genetic improvement and mapping studies | Illumina Hiseq 2500 | [140] | |

| SNP chip-Cowpea iSelect Consortium Array | 51 128 SNPs obtained by WGS sequencing of 37 different cowpea accessions | High throughput genotyping | Illumina HiSeq 2500 | [141] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dhaliwal, S.K.; Talukdar, A.; Gautam, A.; Sharma, P.; Sharma, V.; Kaushik, P. Developments and Prospects in Imperative Underexploited Vegetable Legumes Breeding: A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 9615. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21249615

Dhaliwal SK, Talukdar A, Gautam A, Sharma P, Sharma V, Kaushik P. Developments and Prospects in Imperative Underexploited Vegetable Legumes Breeding: A Review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2020; 21(24):9615. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21249615

Chicago/Turabian StyleDhaliwal, Sandeep Kaur, Akshay Talukdar, Ashish Gautam, Pankaj Sharma, Vinay Sharma, and Prashant Kaushik. 2020. "Developments and Prospects in Imperative Underexploited Vegetable Legumes Breeding: A Review" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 21, no. 24: 9615. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21249615

APA StyleDhaliwal, S. K., Talukdar, A., Gautam, A., Sharma, P., Sharma, V., & Kaushik, P. (2020). Developments and Prospects in Imperative Underexploited Vegetable Legumes Breeding: A Review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 21(24), 9615. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21249615