Unfolding the Association between the Big Five, Frugality, E-Mavenism, and Sustainable Consumption Behavior

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

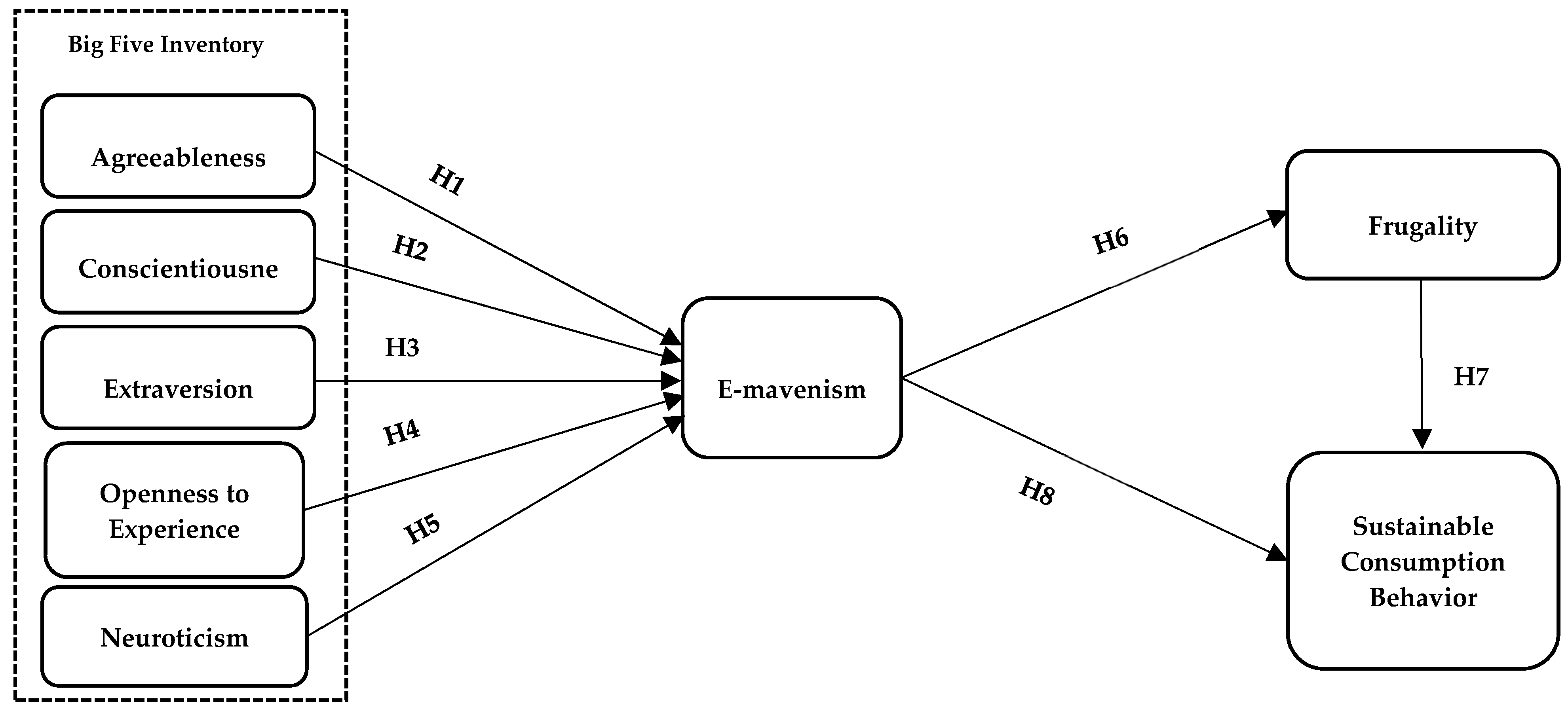

2.1. Conceptual Framework

2.2. The Big Five and E-Mavenism

2.2.1. Agreeableness

2.2.2. Conscientiousness

2.2.3. Extraversion

2.2.4. Neuroticism

2.2.5. Openness to Experience

2.3. E-Mavenism and Frugality

2.4. Frugality and Sustainable Consumption Behavior

2.5. E-Mavenism and Sustainable Consumption Behavior

3. Materials and Method

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Sample Size

3.3. Measurement of Constructs

4. Data Analysis and Results

5. Discussion

6. Implications

7. Limitations

8. Future Recommendations

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Constructs | Items | Scale Adapted |

|---|---|---|

| Agreeableness (AGR) | AGR1. I see myself as someone who likes to cooperate with others. | Agreeableness was measured using three items adapted from [48] which is cross-referenced from the study [111] |

| AGR2. I see myself as someone who is considerate and kind to almost everyone. | ||

| AGR3. I see myself as someone who is sometimes rude to others. (R) | ||

| Conscientiousness (CON) | CON1. I see myself as someone who does things efficiently. | Conscientiousness was measured using three items adapted from [48] which is cross-referenced from the study [111] |

| CON2. I see myself as someone who can be somewhat careless. (R) | ||

| CON3. I see myself as someone who does a thorough job. | ||

| Extraversion (EXT) | EXT1. I see myself as someone who is talkative. | Extraversion was measured using three items adapted from [48] which is cross-referenced from the study [111] |

| EXT2. I see myself as someone who is quiet. (R) | ||

| EXT3. I see myself as someone who is outgoing, sociable. | ||

| Openness to Experience (OTE) | OTE1. I see myself as someone who is original, comes up with new ideas. | Openness to Experience was measured using three items adapted from [48] which is cross-referenced from the study [111] |

| OTE2. I see myself as someone who has an active imagination. | ||

| OTE3. I see myself as someone who is inventive. | ||

| Neuroticism (NEU) | NEU1. I see myself as someone who is relaxed, handles stress well. (R) | Neuroticism was measured using three items adapted from [48] which is cross-referenced from the study [111] |

| NEU2. I see myself as someone who is emotionally stable, not easily upset. (R) | ||

| NEU3. I see myself as someone who remains calm in tense situations. (R) | ||

| E-mavenism (EMV) | EMV1. I like using information collected from the SNSs to introduce new brands and products to my family and friends. | E-mavenism was measured using five items adapted from [64] |

| EMV2. I like helping my family and friends by using SNSs to provide them with information about various kinds of products and services. | ||

| EMV3. My family and friends often ask me to search for the SNSs to provide them with information about products, places, and sites to shop, sales, etc. | ||

| EMV4. If someone wanted to know which SNSs had the best bargains on various types of products and services, I could tell him or her. | ||

| EMV5. My family and friends think of me as a good source of information from the SNSs when it comes to new products, sites to visit, sales, etc. | ||

| Frugality (FRU) | FRU1. I am willing to wait on a purchase I want so that I can save money. | Frugality was measured using four items adapted from [48] which is cross-referenced from the study [27] |

| FRU2. There are things I resist buying today, so I can save for tomorrow. | ||

| FRU3. I believe in being careful about how I spend my money. | ||

| FRU4. I discipline myself to obtain the most from my money. | ||

| Sustainable Consumption Behavior (SCB) | SCB1. I perform daily activities to care for and preserve the environment. | Sustainable Consumption Behavior was measured using three items adapted from [112], and two items adapted from [113] |

| SCB2. How motivated do you feel to make changes in your lifestyle in search of more responsible consumption? | ||

| SCB3. How would you rate your responsible consumption behavior? | ||

| SCB4. I purchase and use products which are environmentally friendly | ||

| * SCB5. I often pay extra money to purchase an environmentally friendly product. |

References

- Liu, D.; Campbell, W.K. The Big Five personality traits, Big Two metatraits and social media: A meta-analysis. J. Res. Personal. 2017, 70, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huseynov, F.; Özkan Yıldırım, S. Online Consumer Typologies and Their Shopping Behaviors in B2C E-Commerce Platforms. Sage Open 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, D.W. Social Media Site Use and the Technology Acceptance Model: Social Media Sites and Organization Success. Ph.D. Thesis, Capella University, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fedorko, I.; Bacik, R.; Gavurova, B. Technology acceptance model in e-commerce segment. Manag. Mark. Chall. Knowl. Soc. 2018, 13, 1242–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungerman, O.; Dedkova, J.; Gurinova, K. The impact of marketing innovation on the competitiveness of enterprises in the context of industry 4.0. J. Compet. 2018, 10, 132–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappas, I.O. User experience in personalized online shopping: A fuzzy-set analysis. Eur. J. Mark. 2018, 52, 1679–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, A.; Maiga, A.; Aïmeur, E. Privacy Protection Issues in Social Networking Sites. In Proceedings of the IEEE/ACS International Conference on Computer Systems and Applications, Rabat, Morocco, 10–13 May 2009; pp. 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, R.; Acquisti, A. Information Revelation and Privacy in Online Social Networks. In Proceedings of the ACM Workshop on Privacy in the Electronic Society, Alexandria, VA, USA, 7 November 2005; pp. 71–80. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Shi, S. A Literature Review of Privacy Research on Social Network Sites. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Multimedia Information Networking and Security, Hubei, China, 18–20 November 2009; pp. 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, A.; Wang, W.Y.; Hashim, K.F. Social Networks and Its Impact on Knowledge Management. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Control System, Computing and Engineering, Penang, Malaysia, 25–27 November 2011; pp. 227–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusco, S.J.; Michael, K.; Michael, M. Using a Social Informatics Framework to Study the Effects of Location-Based Social Networking on Relationships Between People: A Review of Literature. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Symposium on Technology and Society, Wollongong, NSW, Australia, 7–9 June 2010; pp. 157–171. [Google Scholar]

- DeYoung, C.G. Cybernetic Big Five Theory. J. Res. Personal. 2015, 56, 33–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favaretto, R.M.; Dihl, L.; Musse, S.R.; Vilanova, F.; Costa, A.B. Using Big Five Personality Model to Detect Cultural Aspects in Crowds. In Proceedings of the IEEE 2017-30th SIBGRAPI Conference on Graphics, Patterns and Images (SIBGRAPI), Niteroi, Brazil, 17–20 October 2017; pp. 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapp, C.; Ingold, K.; Freitag, M. Personalized networks? How the Big Five personality traits influence the structure of egocentric networks. Soc. Sci. Res. 2019, 77, 148–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borgatti, S.P.; Brass, D.J.; Halgin, D.S. Social Network Research: Confusions, Criticisms, and Controversies. Contemp. Perspect. Organ. Soc. Netw. 2014, 40, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishiguro, I. Extroversion and neuroticism affect the right side of the distribution of network size. Soc. Netw. 2016, 44, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepri, B.; Staiano, J.; Shmueli, E.; Pianesi, F.; Pentland, A. The role of personality in shaping social networks and mediating behavioral change. User Model. User Adapt. Interact. 2016, 26, 143–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitag, M.; Bauer, P.C. Personality Traits and the Propensity to Trust Friends and Strangers. Soc. Sci. J. 2016, 53, 467–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego, A.; Oberski, D. Personality and Political Participation: The Mediation Hypothesis. Polit. Behav. 2012, 34, 425–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, A.S.; Huber, G.A.; Doherty, D.; Dowling, C.M. The BIG FIVE Personality Traits in the Political Arena. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 2011, 14, 265–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondak, J.J. Personality and the Foundations of Political Behavior; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, R.; Landis, B.; Zhang, Z.; Anderson, M.H.; Shaw, J.D.; Kilduff, M. Integrating Personality and Social Networks: A Meta-Analysis of Personality, Network Position, and Work Outcomes in Organizations. Organ. Sci. 2015, 26, 1243–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangwan, S.; Agarwal, P. Effect of consumer self-confidence on information search and dissemination: Mediating role of subjective knowledge. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2019, 43, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feick, L.F.; Price, L.L. The Market Maven: A Diffuser of Marketplace Information. J. Mark. 1987, 51, 83–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, J.Y.; Dempsey, M. Viral marketing: Motivations to forward online content. J. Bus. Res. 2010, 63, 1000–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldsmith, R.E.; Flynn, L.R. Hi, My name Is PAT and I am both Extraverted and a Market Maven: An update and extension of research on Market Mavenism and The Big Five Personality Scale. In Proceedings of the Association of Marketing Theory & Practice, Savannah, Georgia, 26 March 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lastovicka, J.L.; Bettencourt, L.A.; Hughner, R.S.; Kuntze, R.J. Lifestyle of the tight and frugal: Theory and measurement. J. Consum. Res. 1999, 26, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bove, L.L.; Nagpal, A.; Dorsett, A.D.S. Exploring the Determinants of the Frugal Shopper. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2009, 16, 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballantine, P.W.; Creery, S. The Consumption and Disposition Behaviour of Voluntary Simplifiers. J. Consum. Behav. Int. Res. Rev. 2010, 9, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Cai, H.; Florig, H.K. Energy-saving implications from supply chain improvement: An exploratory study on China’s consumer goods retail system. Energy Policy 2016, 95, 411–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikström, F.; Williams, H.; Verghese, K.; Clune, S. The influence of packaging attributes on consumer behaviour in food-packaging life cycle assessment studies-a neglected topic. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 73, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; Lim, Y.; Chang, P.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, M.; Wang, X.; Yu, X.; Lehto, M.R.; Cai, H. Ecolabel’s role in informing sustainable consumption: A naturalistic decision making study using eye tracking glasses. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 218, 685–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diprose, K.; Valentine, G.; Vanderbeck, R.M.; Liu, C.; McQuaid, K. Building Common Cause towards Sustainable Consumption: A Cross-Generational Perspective. Environ. Plan. E Nat. Space 2019, 2, 203–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, J.; Taisch, M.; Mier, M.O. Influencing factors to facilitate sustainable consumption: From the experts’ viewpoints. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhofstadt, E.; Van Ootegem, L.; Defloor, B.; Bleys, B. Linking individuals’ ecological footprint to their subjective well-being. Ecol. Econ. 2016, 127, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofstad, S. Sustainable Consumption. In Proceedings of the Symposium: Sustainable Consumption, Oslo, Norway, 19–20 January 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, P.T., Jr.; McCrae, R.R. Personality Disorders and the Five-Factor Model of Personality. J. Personal. Disord. 1990, 4, 362–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Child, I.L. Personality in Culture. In Handbook of Personality Theory and Research; Rand McNally Chicago: Chicago, IL, USA, 1968; pp. 82–145. [Google Scholar]

- McCrae, R.R.; Costa, P.T., Jr. Reinterpreting the Myers-Briggs type indicator from the perspective of the five-factor model of personality. J. Personal. 1989, 57, 17–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrae, R.R.; John, O.P. An introduction to the five-factor model and its applications. J. Personal. 1992, 60, 175–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Lee, W.-N. Exploring the impact of self-interests on market mavenism and E-mavenism: A Chinese story. J. Internet Commer. 2014, 13, 194–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, G.; Gwinner, K.P.; Swanson, S.R. What makes mavens tick? Exploring the motives of market mavens’ initiation of information diffusion. J. Consum. Mark. 2004, 21, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudbury, L.; Jones, J. The British market maven: An altruistic provider of marketplace information. In Proceedings of the Academy of Marketing Conference, Coventry, UK, 6–8 July 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, C.; Orr, E.S.; Sisic, M.; Arseneault, J.M.; Simmering, M.G.; Orr, R.R. Personality and motivations associated with Facebook use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2009, 25, 578–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Singh, A. Does personality predict organizational citizenship behavior among managerial personnel. J. Indian Acad. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 35, 291–298. [Google Scholar]

- Turkyilmaz, C.A.; Erdem, S.; Uslu, A. The effects of personality traits and website quality on online impulse buying. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 175, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinesen, P.T.; Nørgaard, A.S.; Klemmensen, R. The Civic Personality: Personality and Democratic Citizenship. Political Stud. 2014, 62, 134–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinecke Flynn, L.; Goldsmith, R.E. Filling some gaps in market mavenism research. J. Consum. Behav. 2016, 16, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, P.T., Jr.; McCrae, R.R. The Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R). In The Sage Handbook of Personality Theory and Assessment, Personality Measurement and Testing; Boyle, G.J., Matthews, G., Saklofske, D.H., Eds.; Sage Publications Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008; Volume 2, pp. 179–198. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, G.; Mitchell, V.-W. Identifying, segmenting and profiling online communicators in an internet music context. Int. J. Internet Mark. Advert. 2010, 6, 41–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurawicki, L. Neuromarketing: Exploring the Brain of the Consumer; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra, S.; Reus, T.H.; Zhu, P.; Roelofsen, E.M. The acquisitive nature of extraverted CEOs. Adm. Sci. Q. 2018, 63, 370–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekinci, Y.; Dawes, P.L. Consumer Perceptions of Frontline Service Employee Personality Traits, Interaction Quality, and Consumer Satisfaction. Serv. Ind. J. 2009, 29, 503–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrae, R.R.; Costa, P.T. Empirical and theoretical status of the five-factor model of personality traits. In The SAGE Handbook of Personality Theory and Assessment; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008; Volume 1, pp. 273–294. [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa, T.; Sarason, I.G.; Sarason, B.R. Social Support and Adjustment to a Novel Social Environment. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 1998, 44, 56–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalish, Y.; Robins, G. Psychological predispositions and network structure: The relationship between individual predispositions, structural holes and network closure. Soc. Netw. 2006, 28, 56–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Pan, Y.; Guo, B. The influence of personality traits and social networks on the self-disclosure behavior of social network site users. Internet Res. 2016, 26, 566–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldsmith, R.E.; Horowitz, D. Measuring Motivations for Online Opinion Seeking. J. Interact. Advert. 2006, 6, 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampel, J.; Bhalla, A. The role of status seeking in online communities: Giving the gift of experience. J. Comput. Mediat. Commun. 2007, 12, 434–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollock, P. The economies ol online cooperation: Gifts and Public Goods in Cyberspace. In Communities in Cyberspace; Smith, M.A., Kollock, P., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 1999; pp. 220–239. [Google Scholar]

- Caliskan, A. Applying the Right Relationship Marketing Strategy through Big Five Personality Traits. J. Relatsh. Mark. 2019, 18, 196–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, D.C. Materialism: Profiles of agreeableness and neuroticism. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2014, 56, 197–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Nadkarni, S.; Mariam, M. Dispositional sources of managerial discretion: CEO ideology, CEO personality, and firm strategies. Adm. Sci. Q. 2018, 64, 855–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belch, M.A.; Krentler, K.A.; Willis-Flurry, L.A. Teen internet mavens: Influence in family decision making. J. Bus. Res. 2005, 58, 569–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdheim, J.; Wang, M.; Zickar, M.J. Linking the Big Five Personality Constructs to Organizational Commitment. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2006, 41, 959–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrae, R.R.; Costa, P.T., Jr. Personality trait structure as a human universal. Am. Psychol. 1997, 52, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, H.; Steenkamp, J.-B.E. Exploratory Consumer Buying Behavior: Conceptualization and Measurement. Int. J. Res. Mark. 1996, 13, 121–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, K.; McElroy, J.C. The influence of personality on Facebook usage, wall postings, and regret. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2012, 28, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruvio, A.; Shoham, A. Innovativeness, exploratory behavior, market mavenship, and opinion leadership: An empirical examination in the Asian context. Psychol. Mark. 2007, 24, 703–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrett, A.; Straker, K.; Wrigley, C. Digital Channels for Building Collaborative Consumption Communities. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2017, 11, 160–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darley, W.; Lim, J.-S. Mavenism and e-maven propensity: Antecedents, mediators and transferability. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2018, 12, 293–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, S.J.; Pressey, A.D. Cyber-mavens and online flow experiences: Evidence from virtual worlds. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2016, 111, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Forsyth, J.E.; Lavoie, J.; McGuire, T. Managing Expectations for Value. Mckinsey Q. 2000, 4, 12–19. [Google Scholar]

- Belch, G.E.; Belch, M.A. Advertising and Promotion: An Integrated Marketing Communications Perspective 6th; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Awais, M.; Samin, T.; Gulzar, M.A.; Aljuaid, H.; Ahmad, M.; Mazzara, M. User Acceptance of HUMP-Model: The Role of E-Mavenism and Polychronicity. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 174972–174985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldsmith, R.E.; Flynn, L.R. The Etiology of Frugal Spending: A Partial Replication and Extension. Compr. Psychol. 2015, 4, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatzel, M. Value seekers, big spenders, non-spenders, and experiencers: Consumption, personality, and well-being. In Consumption and Well-Being in the Material World; Tatzel, M., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 75–108. [Google Scholar]

- Roccas, S.; Sagiv, L.; Schwartz, S.H.; Knafo, A. The big five personality factors and personal values. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2002, 28, 789–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardhi, F.; Arnould, E.J. Thrift Shopping: Combining Utilitarian Thrift and Hedonic Treat Benefits. J. Consum. Behav. Int. Res. Rev. 2005, 4, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbany, J.E.; Dickson, P.R.; Kalapurakal, R. Price search in the retail grocery market. J. Mark. 1996, 60, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, C.; Hiltz, S.R.; Widmeyer, G. Understanding Development and Usage of Social Networking Sites: The Social Software Performance Model. In Proceedings of the IEEE 2008-41st Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS), Waikoloa, HI, USA, 7–10 January 2008; p. 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapia-Fonllem, C.; Corral-Verdugo, V.; Fraijo-Sing, B.; Durón-Ramos, M. Assessing sustainable behavior and its correlates: A measure of pro-ecological, frugal, altruistic and equitable actions. Sustainability 2013, 5, 711–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, P.; Smith, S.T.; Segrist, D.J. Too cheap to chug: Frugality as a buffer against college-student drinking. J. Consum. Behav. 2010, 9, 228–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albinsson, P.A.; Wolf, M.; Kopf, D.A. Anti-Consumption in East Germany: Consumer Resistance to Hyperconsumption. J. Consum. Behav. 2010, 9, 412–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rick, S.I.; Cryder, C.E.; Loewenstein, G. Tightwads and spendthrifts. J. Consum. Res. 2007, 34, 767–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkner, C. Thrifty Brits: Economic Austerity in the UK Has given Rise to a More Frugal British Consumer. Mark. News, 8 August 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Egol, M.; Clyde, A.; Rangan, K.; Sanderson, R. The New Consumer Frugality: Adapting to the Enduring Shift in US Consumer Spending and Behavior; Booz & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wells, W.D.; Tigert, D.J.; Activities, I. Activities, interests and opinions. J. Advert. Res. 1971, 11, 27–35. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, D.; Moraes, C. Voluntary simplicity: An exploration of market interactions. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2009, 33, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepper, M.; Jackson, T.; Uzzell, D. An examination of the values that motivate socially conscious and frugal consumer behaviours. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2009, 33, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, D.C.; Nique, W.M.; Añaña, E.d.S.; Herter, M.M. Green consumer values: How do personal values influence environmentally responsible water consumption? Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2011, 35, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newholm, T.; Shaw, D. Studying the ethical consumer: A review of research. J. Consum. Behav. Int. Res. Rev. 2007, 6, 253–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, D. Thrifty, Green or Frugal: Reflections on Sustainable Consumption in a Changing Economic Climate. Geoforum 2011, 42, 550–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marucheck, A.; Greis, N.; Mena, C.; Cai, L. Product safety and security in the global supply chain: Issues, challenges and research opportunities. J. Oper. Manag. 2011, 29, 707–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meise, J.N.; Rudolph, T.; Kenning, P.; Phillips, D.M. Feed them facts: Value perceptions and consumer use of sustainability-related product information. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2014, 21, 510–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owusu, V.; Owusu Anifori, M. Consumer willingness to pay a premium for organic fruit and vegetable in Ghana. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2013, 16, 67–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Zeng, Y.; Fong, Q.; Lone, T.; Liu, Y. Chinese consumers’ willingness to pay for green-and eco-labeled seafood. Food Control 2012, 28, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, E.; Dulsrud, A. Will consumers save the world? The framing of political consumerism. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2007, 20, 469–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldsmith, R.E.; Flynn, L.R.; Clark, R.A. The Etiology of the Frugal Consumer. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2014, 21, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, B.C. Advances in science and technology through frugality. IEEE Eng. Manag. Rev. 2017, 45, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiedmann, K.-P.; Walsh, G.; Mitchell, V.-W. The Mannmaven: An agent for diffusing market information. J. Mark. Commun. 2001, 7, 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, M.; Kowalski, S.; Nohlberg, M.; Tjoa, S. Towards Automating Social Engineering Using Social Networking Sites. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computational Science and Engineering, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 29–31 August 2009; pp. 117–124. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, S.; Ogden, D.T. To Buy or Not to Buy? A Social Dilemma Perspective on Green Buying. J. Consum. Mark. 2009, 26, 376–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thøgersen, J. Unsustainable Consumption: Basic Causes and Implications for Policy. Eur. Psychol. 2014, 19, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockström, J.; Steffen, W.L.; Noone, K.; Persson, Å.; Chapin, F.S., III; Lambin, E.; Lenton, T.M.; Scheffer, M.; Folke, C.; Schellnhuber, H.J. Planetary Boundaries: Exploring the Safe Operating Space for Humanity. Ecol. Soc. 2009, 14, 32. Available online: http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol14/iss2/art32/ (accessed on 1 January 2009). [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Qu, Y.; Lei, Z.; Jia, H. Understanding the evolution of sustainable consumption research. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 25, 414–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger, S.M.; Fischer, D.; Schrader, U. Measuring What Matters in Sustainable Consumption: An Integrative Framework for the Selection of Relevant Behaviors. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 26, 18–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Hardy, A.; Ooi, C.S. Researching Chinese tourists on the move. J. China Tour. Res. 2019, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutia, S.; Chauhdary, S.H.; Iwendi, C.; Liu, L.; Yong, W.; Bashir, A.K. Socio-Technological factors affecting user’s adoption of eHealth functionalities: A case study of China and Ukraine eHealth systems. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 90777–90788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Anderson, R.; Tatham, R.; Black, W. Multivariate Data Analysis with Readings, 5th ed.; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Flynn, L.R.; Swilley, E. Resisting Change: Scale validation with a New, Short Measure of the BIG FIVE. Proc. Assoc. Mark. Theory Pract. 2007, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa-García, E.; García-Machado, J.; Pérez-Bustamante Yábar, D. Modeling the Social Factors that Determine Sustainable Consumption Behavior in the Community of Madrid. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quoquab, F.; Mohammad, J.; Sukari, N.N. A multiple-item scale for measuring “sustainable consumption behaviour” construct: Development and psychometric evaluation. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2019, 31, 791–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R. Understanding Culture’s Influence on Behavior; Harcourt Brace Jovanovich College Publishers: San Diego, CA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. Specification, Evaluation, and Interpretation of Structural Equation Models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2012, 40, 8–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, M.; Porter, G. The impact of cognitive and other factors on the perceived usefulness of OLAP. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2004, 45, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, O.P.; Naumann, L.P.; Soto, C.J. Paradigm shift to the integrative big five trait taxonomy. In Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research, 3rd ed.; John, O.P., Robins, R.W., Pervin, L.A., Eds.; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 114–158. [Google Scholar]

- Block, J. The five-factor framing of personality and beyond: Some ruminations. Psychol. Inq. 2010, 21, 2–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, L.R. An Alternative Description of Personality: The BIG FIVE Factor Structure. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1990, 59, 1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Hsieh, P.; Yen, H.R. Engaging customers in value co-creation: The emergence of customer readiness. In Proceedings of the 2011 International Joint Conference on Service Sciences, Taipei, Taiwan, 25–27 May 2011; pp. 135–139. [Google Scholar]

- Sudbury-Riley, L. The baby boomer market maven in the United Kingdom: An experienced diffuser of marketplace information. J. Mark. Manag. 2016, 32, 716–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, S. Dragging market mavens to promote apps repatronage intention: The forgotten market segment. J. Promot. Manag. 2018, 24, 511–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Lee, W.-N. Testing the concepts of market mavenism and opinion leadership in China. Am. J. Bus. 2015, 30, 178–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lončarić, D.; Perišić Prodan, M.; Dlačić, J. The role of market mavens in co-creating tourist experiences and increasing loyalty to service providers. Econ. Res. Ekon. Istraživanja 2019, 32, 2252–2268. [Google Scholar]

- Calder, B.J.; Phillips, L.W.; Tybout, A.M. Designing research for application. J. Consum. Res. 1981, 8, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phipps, M.; Ozanne, L.K.; Luchs, M.G.; Subrahmanyan, S.; Kapitan, S.; Catlin, J.R.; Gau, R.; Naylor, R.W.; Rose, R.L.; Simpson, B. Understanding the inherent complexity of sustainable consumption: A social cognitive framework. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1227–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luchs, M.; Naylor, R.W.; Rose, R.L.; Catlin, J.R.; Gau, R.; Kapitan, S.; Mish, J.; Ozanne, L.; Phipps, M.; Simpson, B. Toward a Sustainable Marketplace: Expanding Options and Benefits for Consumers. J. Res. Consum. 2011, 19, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, T.; Michaelis, L. Policies for Sustainable Consumption; A Report to the Sustainable Development Commission; Sustainable Development Commission: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, J. Word of Mouth and Interpersonal Communication: A Review and Directions for Future Research. J. Consum. Psychol. 2014, 24, 586–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haenlein, M.; Libai, B. Seeding, Referral, and Recommendation: Creating Profitable Word-of-Mouth Programs. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2017, 59, 68–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowen, J.C.; Park, S.; Zablah, A. Toward a theory of motivation and personality with application to word-of-mouth communications. J. Bus. Res. 2007, 60, 590–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wien, A.H.; Olsen, S.O. Producing word of mouth–a matter of self-confidence? Investigating a dual effect of consumer self-confidence on WOM. Australas. Mark. J. 2017, 25, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandrov, A.; Lilly, B.; Babakus, E. The effects of social-and self-motives on the intentions to share positive and negative word of mouth. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2013, 41, 531–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, A.M.; Donthu, N.; Kumar, V. Investigating How Word-of-Mouth Conversations about Brands Influence Purchase and Retransmission Intentions. J. Mark. Res. 2016, 53, 225–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldsmith, R.E. Brand Engagement and Brand Loyalty. In Branding and Sustainable Competitive Advantage: Building Virtual Presence; IGI Global: London, UK, 2012; pp. 121–135. [Google Scholar]

- Ocampo, S.; Perdomo-Ortiz, J.; Castaño, L. The concept of socially responsible consumption and its measurement. A review of the literature. Manag. Stud. 2014, 30, 287–300. [Google Scholar]

- Awais, M.; Samin, T.; Gulzar, M.A.; Hwang, J. The Sustainable Development of the China Pakistan Economic Corridor: Synergy among Economic, Social, and Environmental Sustainability. Sustainability 2019, 11, 7044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Constructs and Measurement Items | Standardized Loadings a,b | Construct Reliability | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agreeableness | 0.927 | 0.925 | |

| AGR1 | 0.881 | ||

| AGR2 | 0.901 | ||

| AGR3 | 0.917 | ||

| Conscientiousness | 0.890 | 0.888 | |

| CON1 | 0.804 | ||

| CON2 | 0.909 | ||

| CON3 | 0.846 | ||

| Extraversion | 0.890 | 0.887 | |

| EXT1 | 0.826 | ||

| EXT2 | 0.816 | ||

| EXT3 | 0.917 | ||

| Openness to Experience | 0.957 | 0.953 | |

| OTE1 | 0.806 | ||

| OTE2 | 0.998 | ||

| OTE3 | 0.901 | ||

| Neuroticism | 0.961 | 0.961 | |

| NEU1 | 0.947 | ||

| NEU2 | 0.976 | ||

| NEU3 | 0.909 | ||

| E-mavenism | 0.907 | 0.905 | |

| EM1 | 0.755 | ||

| EM2 | 0.828 | ||

| EM3 | 0.821 | ||

| EM4 | 0.862 | ||

| EM5 | 0.794 | ||

| Sustainable Consumption Behavior | 0.978 | 0.978 | |

| SCB1 | 0.969 | ||

| SCB2 | 0.966 | ||

| SCB3 | 0.967 | ||

| SCB4 | 0.926 | ||

| Frugality | 0.891 | 0.891 | |

| FRU1 | 0.856 | ||

| FRU2 | 0.847 | ||

| FRU3 | 0.821 | ||

| FRU4 | 0.753 |

| Constructs | AVE | MSV | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCB | EM | FRU | NEU | OTE | ARG | CON | EXT | |||

| 1. SCB Sustainable Consumption Behavior | 0.916 | 0.304 | 0.957 | |||||||

| 2. EM E-mavenism | 0.661 | 0.350 | 0.551 *** | 0.813 | ||||||

| 3. FRU Frugality | 0.673 | 0.255 | 0.333 *** | 0.505 *** | 0.820 | |||||

| 4. NEU Neuroticism | 0.892 | 0.163 | 0.404 *** | 0.400 *** | 0.378 *** | 0.945 | ||||

| 5. OTE Openness to Experience | 0.883 | 0.028 | 0.110 * | 0.166 ** | 0.090 † | 0.130 * | 0.940 | |||

| 6. ARG Agreeableness | 0.810 | 0.115 | 0.164 ** | 0.299 *** | 0.112 * | 0.110 * | 0.108 * | 0.900 | ||

| 7. CON Conscientiousness | 0.730 | 0.134 | 0.165 ** | 0.366 *** | 0.213 *** | 0.214 *** | 0.089 † | 0.339 *** | 0.854 | |

| 8. EXT Extraversion | 0.729 | 0.350 | 0.484 *** | 0.592 *** | 0.400 *** | 0.319 *** | 0.131 * | 0.178 ** | 0.222 *** | 0.854 |

| CMIN | |

| Chi-Square (x2) or CMIN | 436.286 |

| Degree of Freedom (DF) | 322 |

| Normed Chi-Square (CMIN/DF) | 1.355 |

| GFI, SRMR | |

| Goodness of Fit Index (GFI) | 0.927 |

| Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index (AGFI) | 0.908 |

| Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) | 0.034 |

| RMSEA | |

| Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) | 0.030 |

| Probability of Close Fit (PCLOSE) | 1.000 |

| Baseline Comparison | |

| Normed Fit Index (NFI) | 0.964 |

| Relative Fit Index (RFI) | 0.957 |

| Incremental Fit Measures (IFI) | 0.990 |

| Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) | 0.988 |

| Comparative Fit Index (CFI) | 0.990 |

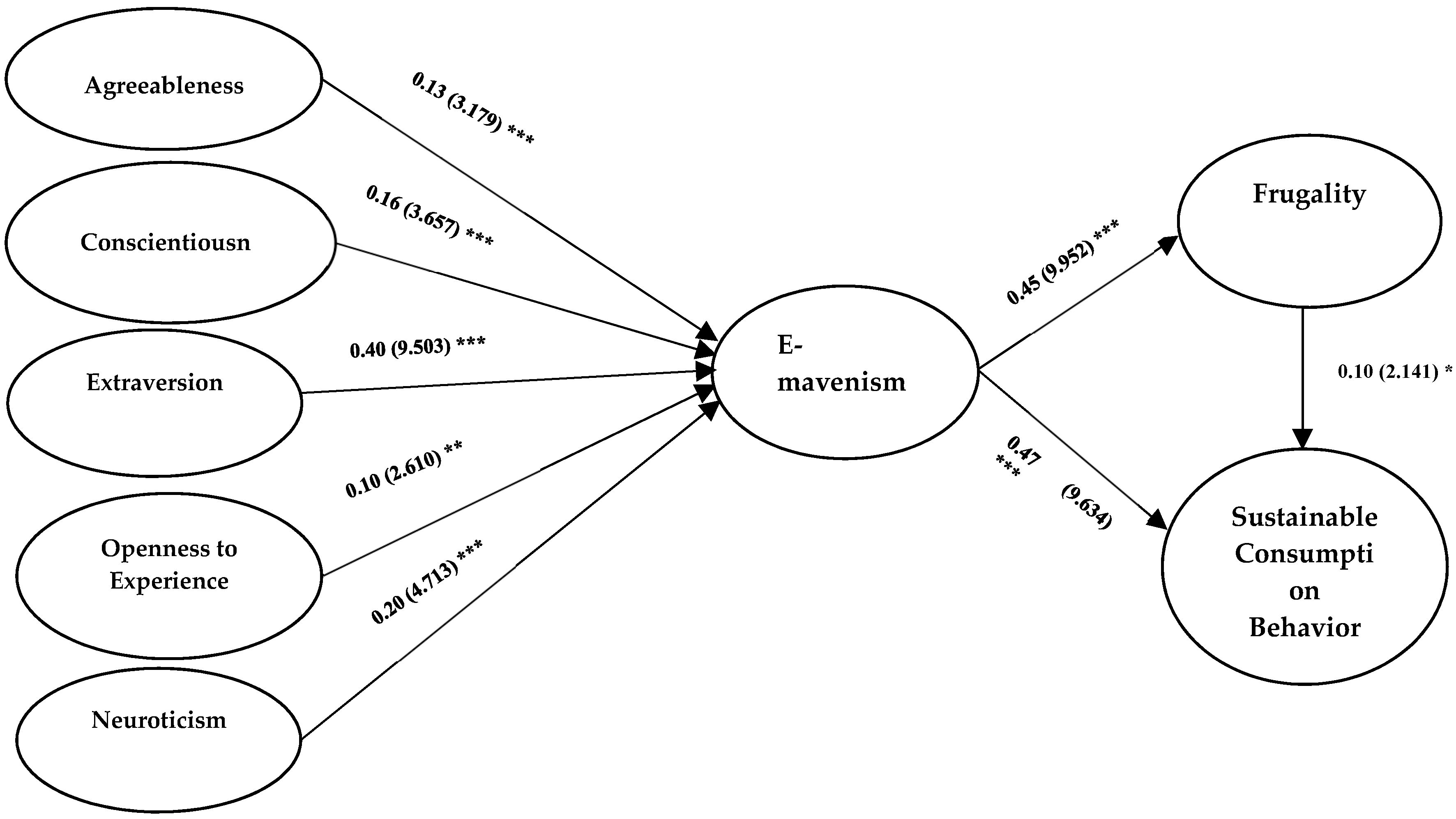

| Path | Regression Weights | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimates | S.E. | C.R. | p | |

| Hypothesis 1 (H1) | ||||

| E-mavenism ← Agreeableness | 0.203 | 0.064 | 3.179 | *** |

| Hypothesis 2 (H2) | ||||

| E-mavenism ← Conscientiousness | 0.191 | 0.052 | 3.657 | *** |

| Hypothesis 3 (H3) | ||||

| E-mavenism ← Extraversion | 0.404 | 0.043 | 9.503 | *** |

| Hypothesis 4 (H4) | ||||

| E-mavenism ← Openness to Experience | 0.122 | 0.047 | 2.610 | ** |

| Hypothesis 5 (H5) | ||||

| E-mavenism ← Neuroticism | 0.156 | 0.033 | 4.713 | *** |

| Hypothesis 6 (H6) | ||||

| Frugality ← E-mavenism | 0.487 | 0.049 | 9.952 | *** |

| Hypothesis 7 (H7) | ||||

| Sustainable Consumption Behavior ← Frugality | 0.146 | 0.068 | 2.141 | * |

| Hypothesis 8 (H8) | ||||

| Sustainable Consumption Behavior ← E-mavenism | 0.711 | 0.074 | 9.634 | *** |

| Hypotheses | Supported/Not Supported |

|---|---|

| Hypothesis 1(H1). Agreeableness positively affects e-mavenism to use SNSs. | Supported |

| Hypothesis 2 (H2). Conscientiousness positively affects e-mavenism to use SNSs. | Supported |

| Hypothesis 3 (H3). Extraversion positively affects e-mavenism to use SNSs. | Supported |

| Hypothesis 4 (H4). Neuroticism positively affects e-mavenism to use SNSs. | Supported |

| Hypothesis 5 (H5). Openness to experience positively affects e-mavenism to use SNSs. | Supported |

| Hypothesis 6 (H6). E-mavenism has a positive influence on frugality to use SNSs. | Supported |

| Hypothesis 7 (H7). Frugality positively affects sustainable consumption behavior to use SNSs. | Supported |

| Hypothesis 8 (H8). E-mavenism positively affects sustainable consumption behavior to use SNSs. | Supported |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Awais, M.; Samin, T.; Gulzar, M.A.; Hwang, J.; Zubair, M. Unfolding the Association between the Big Five, Frugality, E-Mavenism, and Sustainable Consumption Behavior. Sustainability 2020, 12, 490. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12020490

Awais M, Samin T, Gulzar MA, Hwang J, Zubair M. Unfolding the Association between the Big Five, Frugality, E-Mavenism, and Sustainable Consumption Behavior. Sustainability. 2020; 12(2):490. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12020490

Chicago/Turabian StyleAwais, Muhammad, Tanzila Samin, Muhammad Awais Gulzar, Jinsoo Hwang, and Muhammad Zubair. 2020. "Unfolding the Association between the Big Five, Frugality, E-Mavenism, and Sustainable Consumption Behavior" Sustainability 12, no. 2: 490. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12020490

APA StyleAwais, M., Samin, T., Gulzar, M. A., Hwang, J., & Zubair, M. (2020). Unfolding the Association between the Big Five, Frugality, E-Mavenism, and Sustainable Consumption Behavior. Sustainability, 12(2), 490. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12020490