1. Introduction

The aim of this paper is to investigate whether Vojvodina wine routes can be a significant tourist destination in the region. Their existence and role in the specific forms of tourism were expressed by the respondents in this research. The results obtained after analyzing the respondents’ answers, using different methods, may indicate the importance of these wine routes for sustainable tourism development. This is specifically provided by the students’ answers, which emphasize the importance of wine routes offered for tourists, as they are the subject of numerous interests, as evidenced by similar studies. Students acquired this information through the theoretical study of wine tourism, and through practical fieldwork. The task in this paper is to analyze all relevant resources, which were identified by the respondents, then evaluated, ranked and analyzed. For sustainable tourism development, this would mean that after the identification of these resources, and proper valuation, they can be positioned in Vojvodina in the tourism market, as well as a significant wine tourism destination in the region. A specific tourism product, such as wine routes, can be of great importance for the sustainable development of the country. It can integrate other branches of industry and the aforementioned forms of tourism in order to promote the national economy. This is also the aim of this paper.

The methods that were used in the study are the methods of analysis, methods of questionnaires, methods of comparative analysis of the obtained results and the method of correlation using the SPSS software. The main conclusion of the research is that by developing wine tourism in Vojvodina, we can influence economic development of the region. At the same time, development of this specific form of tourism would represent the achievement of ecological, economic, and socio-cultural benefits for the destination, which is one of the basic postulates of sustainable tourism development [

1].

2. Literature Review

Wine tourism represents one of the tourism forms that have been quickly integrated and have adapted to the global tourist market. The need to know and analyse this tourism form has occurred following the change in the tourist demand favoring the practice of tourism in the middle of nature and the discovery of local traditions. The dynamic of this tourism form is supported by the wider geographic spread at the global level, both in the “Old World”, in countries like: Italy, France, Spain, Greece, Serbia, and Romania [

2,

3,

4,

5], but especially in the “New World”, where Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, and the USA stand out [

6,

7,

8,

9].

The beginnings of wine tourism date back to the second half of the 19th century, when the visits to vineyards became a component of the travel destinations in the middle of nature [

5]. In the last decades of the 19th century, wine—this divine drink—started to become a main attractive factor within the organised tourist packages, and, thus, some of the wine-growing regions, like Tuscany (Italy), Alsace, Bordeaux, Burgundy, Champagne (France), Rhine Valley (Germany), and Douro Valley (Portugal) became important tourist attractions [

10].

Many attempts to define wine tourism come from various researchers in the tourism marketing field and the main focus is on the tourists’ motivations to visit a wine-growing region, and their experiences in these regions. Thus, Hall and Macionis [

11] defined wine tourism as being “visitation to vineyards, wineries, wine festivals and wine shows for which grape wine tasting and/or experiencing the attributes of a grape wine region are the prime motivating factors for visitors”. Geibler, quoted by Ungureanu, offers a more complex definition [

12] (p. 85), stating that wine tourism “includes a wide range of experiences built on the occasion of visits that tourists make to the wine producers, in the wine-growing regions or while participating to wine-related events and shows—including wine tastings, wine associated to food products, the pleasure of discovering the surroundings of the region, one-day trips or longer leisure trips and the experience of a range of lifestyles and cultural activities”. According to Manilă [

13], the geographers are the ones who introduced the concept of landscape in the definition of wine tourism, as well as the concept of “terroir” or “winescape”. The territory plays a very important role, being defined as a basis or a reference point for the wine tourism which this development offers. The territory, with its deep features or “le terroir” (French term used to describe the pedoclimatic conditions where the vines grow in a certain wine region), is the basis of wine culture development. The quality of the wine and, therefore, the tourist attraction, cannot be achieved without the quality of the terroir where the vines are grown. The concept of “winescape”, introduced for the first time by Peters [

14], refers to the features of a wine region offered by: the presence of vineyards, the wine production activity and the wineries where the wine is produced and stored. Subsequently, the term is increasingly used in the specialty literature on wine tourism, such as the studies conducted by Brunori and Rossi [

15], Pivac [

16], Soare and Costachie [

17]. Beyond the wine and wine-growing, according to Alebaki and Lakovidou [

18] (p. 123), wine tourism is “marked” by the entire wine-growing region and its features.

Although in some areas, wine tourism is considered to be only emergent, in others it becomes more and more popular, because tourism and food are increasingly combined in wine tours and in other forms of agro-tourism [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. Wine tourism is well organised in the “Old World” [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30].

In Europe, wine tourism has often been associated with the official wine routes and roads [

21]. The majority of the European wine routes are tourist objectives that have evolved from individual attractions, becoming authentic and diversified destinations themselves, capitalizing their cultural elements and landscapes, enriched by the reputation of the wines and the specific territory [

31] (p. 75).

Wine routes have been a significant tourist activity since the 1920s in Germany (on the slopes of the Rhine Valley with spectacular views over the vineyards and the wine-growing villages, bearing a wonderful medieval architecture), in France (Alsace, Burgundy and Champagne), and later in California (The Napa Valley Wine Train), South Africa (Stellenbosch Wine Routes) or Australia (Tamar Valley Wine Route) [

13].

The attractiveness of wine routes has increased as soon as the wine manufacturers have facilitated the access of tourists on their properties through their mutual collaboration with the hotel owners, the restaurant owners and the local authorities.

The interest in wine routes knows a considerable growth after 1970 in the Western European developed countries, a period that coincides with the “explosion of tourism”, the development of mass tourism [

32]. Additionally, there appears the need to individualize the tourist offers for social groups with different preferences and tastes, leading to the definition of themed routes as “themed” attractions. Wine routes can become interesting tourist destinations due to the themed and travel experience they propose, connecting places, events and cultural heritage [

33,

34,

35]. The process of individualization of wine routes as tourist products is seen as a new principle to protect, revive, use and present the wine heritage.

Within a wine route, the wine cellars try to offer a supplementary offer to the tourists, progressively generating added value to the destination, energizing the traditional agricultural sector and innovating wine products, but also important events for the local viticulture. The study conducted by Ungureanu (2015) stands out and states that the “Wine Route” may become an efficient instrument to increase the attractiveness of the wine-growing potential of a region with a controlled designation of origin, under the conditions of providing a varied range of tourist services [

12] (pp. 195–210).

Coroș et al. [

29] analyse in another study if and how the vineyards and the wine cellars from the old wine region, Weinland (Transylvania), crossed by an attractive wine route, can approach a sustainable development. Those elements that motivate the Romanian and foreign tourists to visit this destination are shaped and the need to establish a “Destination Management Organisation” (DMO) is highlighted, which may be able to manage the interests of all the stakeholders within the limits of a sustainable development.

Soare et al. [

17] underline the contribution of wine routes to the improvement of marketing strategies for wine products, the economic performance and the efficiency of wine manufacturers’ performance, and Carmichael and Sense analyse the competitiveness and the sustainability of wine-growing destinations and, thus, have developed a destination development model [

36] (pp. 162–165).

An investigation on the profile and the motivations of European wine tourists on the Sherry Wine Route from Spain shows that the tourists are very satisfied with the visits to the wineries, underlining at the same time the relationship between the wine, the local cuisine and the growing interest of travellers in everything related to the wine culture [

37].

The process of shaping cultural (gastronomic or wine) routes as tourist products is considered by some authors a new principle to protect, revive, use and present a cultural heritage [

38]. Therefore, we have to underline that wine is part of the cultural and social history of the region, and an element of the local population’s identity.

3. Materials and Methodological Approach

The research has been carried out through three steps. The first one has consisted in investigating the wine area study and the wine routes of Vojvodina. In the second stage, in order to explore the importance of wine tourism for sustainable development, the authors conducted a survey among tourism youth in Belgrade. The authors considered that tourism students represented a significant basis in the development of staff for educational tourism. Young people (18–22 years) were interviewed, from different years of bachelor studies, of which 55 were male and 95 females. The survey was conducted between students who have acquired theoretical knowledge on the types and quality of international wines and wine in Serbia. They are introduced with the types of wines produced in the territory of Vojvodina, as well as the possibilities of their involvement in the creation of new tourist products and wine routes of Vojvodina. In addition to theoretical knowledge, this group of students visited some wine routes. Consequently, they represent a reference group that can evaluate the questions raised in the research process.

With 150 valid questionnaires collected, they were asked specific questions regarding the importance of wine tourism and wine routes for the development of tourism offers and sustainable tourism in Vojvodina region. The answers are ranked by relevance on a scale of 1 to 5 (Likert’s Scale), 1—I completely disagree, 2—I partially disagree, 3—neutral point of view, 4—I partially agree, 5—I completely agree. Finally, at the third step, all the obtained data have been analyzed and interpreted. The use of descriptive statistics has been necessary to reach a complete panoramic view and subsequently, the correlation analysis has allowed us to understand and achieve the aim.

3.1. Area Study

Many destinations in the northern part of Serbia in Vojvodina have the potential to develop sustainable forms of tourism. Observing Vojvodina, there are relevant potentials for the development of rural tourism because this territory is famous for its rural areas, granges, and numerous small settlements with their distinctive narrow streets. Fruška Gora and Vršac Mountains create the possibility for the development of mountain tourism [

39]. The cities of Belgrade and Novi Sad are the leading city destinations in Serbia, and due to their vicinity, they represent important outgoing centers for destinations in Vojvodina. Since the Danube is the main Pan-European corridor and the most strategic river in Europe, it creates favorable conditions for the development of nautical tourism in this territory [

40]. In addition to the aforementioned forms of tourism, within Vojvodina, there are also precious resources for the development of the transitory, cultural, the tourism of protected natural areas, geotourism, ecotourism, and nature-based tourism. In addition, extremely important for the development of wine tourism are a favorable climate, land composition, and numerous vineyards.

This form, in combination with other forms of tourism, can make Vojvodina a competitive tourist destination in the region. Vojvodina has a rich history of viniculture, along with many other interesting features such as natural beauty, cultural and historical monuments, events, and other values [

41]. Many countries tend to use these possibilities and work on the improvement of their cultural heritage through developing innovative sustainable tourism programs, combining technology with experiences, thus creating traditional tourism services [

42].Wine and quality wines represent every country’s significant tourism potential because besides basic wine elements such as wine fairs, wine events, wine cellars as attractions [

43], grape harvesting, wine auctions, wine tasting, and promotions, they integrate complementary tourism motives [

44], such as geographical and ethnographical motives, into a unique and authentic tourism product of a country, known as “Wine Routes” [

45]. Since Vojvodina was a part of the former Pannonian Sea [

46], the predominantly sandy soils caused the development of a specific vine with grapes that are now being produced into quality wines and some of them are called “Sand Wines”.

The Republic of Serbia has 22,149.97 ha of the vineyards, of which 4667.25 ha makes table wine sorts, and 17,482.72 ha is under wine sorts (

Table 1 and

Table 2). Out of 17,482.72 ha under wine sorts, 2631.08 ha is under the geographical origin wine cultivation sorts, and 14,851.64 ha is under sorts for wine cultivation without geographical origin [

47]. Of the total area under the vineyards, 22.7% is in the region of Vojvodina. The Serbian province, Vojvodina, is the study area in our work and therefore has great significance.

The diversity of Vojvodina’s locality, primarily climate diversity, land, and geographical position, results in the presence of different sorts of wine [

16]. The greatest number of vineyards are located along the three biggest rivers flowing through Vojvodina: Sava, Danube, and Tisa. There are three wine regions in the Autonomous Province of Vojvodina (

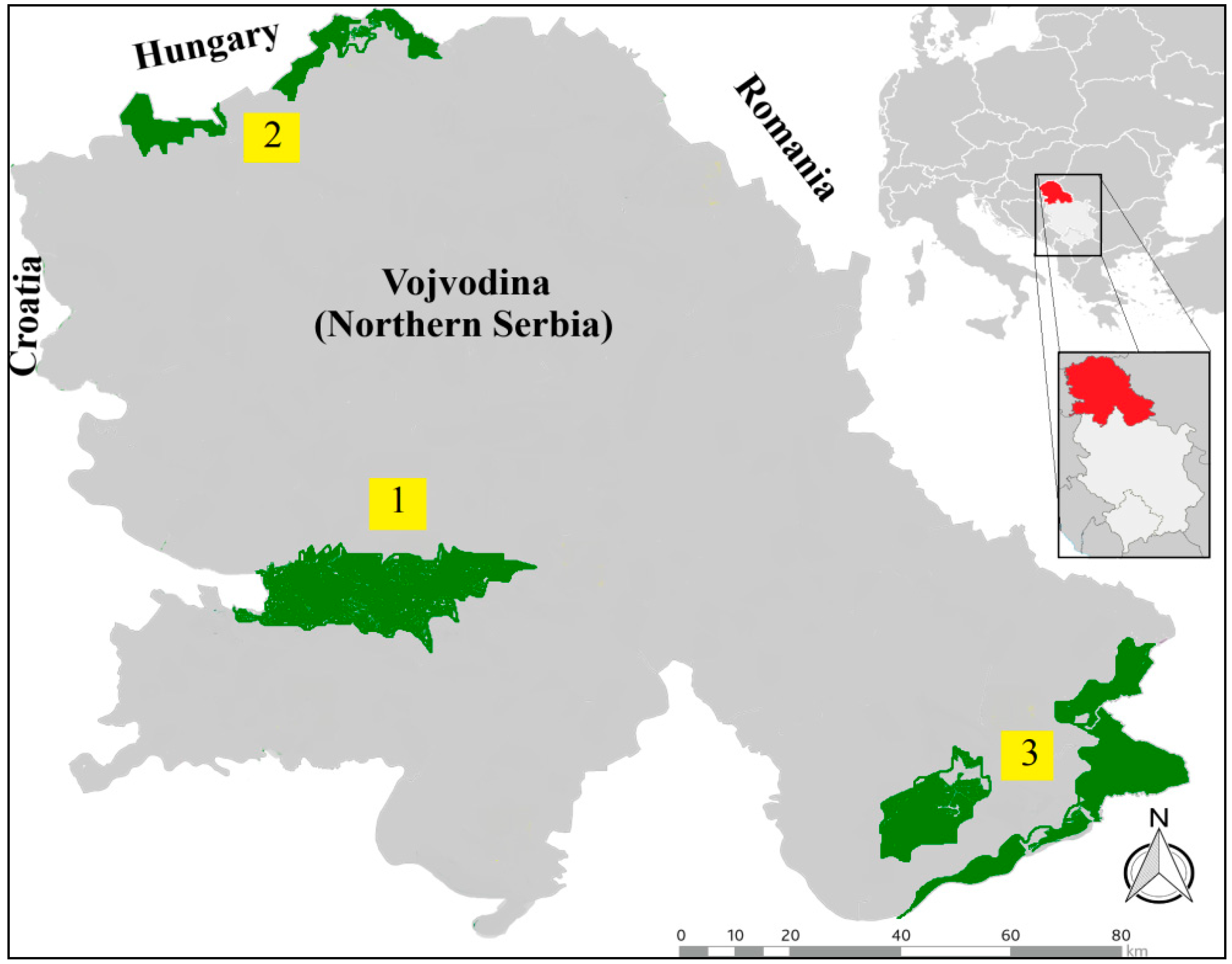

Figure 1).

Srem Region extends mainly on the slopes of Fruška Gora. There are numerous small producers in the Srem region, which are mainly concentrated in Sremski Karlovci. The specific wine is Bermet, a dessert type, which was served at the Viennese court and was on wine menu on the “Titanic”. The most relevant wineries of this region are “Do Kraja Sveta”, “Kiš”, “Kovačević”, “Mačkov Podrum”, “Vindulo”, and “Živković”.

Subotica-Horgoš Region is located in the north of Serbia, in the vicinity of Subotica to the Horgoš and Hungarian border. It is comprised of the Palić and Horgoš vineyards. The soil is mainly sandy—the remains of the Pannonian Sea, so these wines are often called “Sand Wines”. Significant wineries in this region are “Vinarija Čoka”, “Dibonis”, and “WOW”.

Banat Region is located in the northeast of Serbia, in the vicinity of Vršac, near the Romanian border. The most significant wineries of this region are Vršac, Kovin, and Biserno Ostrvo from which the famous Muskat Krokan comes. Out of the producers, the most important are the Vršac wineries which cover 1700 ha.

Apart from the festivities of vineyards, wine, and viniculture in these regions of Vojvodina, there is a great number of events relevant for the development of wine tourism. These events record a great number of visitors and exhibitors. The most popular wine event in Autonomous Province of Vojvodina are “Karlovac Vintage Days” in Sremski Karlovci; “Pudarski Dani” and St. Trifun’s celebration in Irig; “Dani Vina” in Rivica; “Interfest” and “Dan Mladog Portugizera” in Novi Sad; “Berbanski Dani” in Palić; “Grožđebal” in Sonta; “Banoštorski Dani Grožđa” in Banoštor; and “Vinofest” and “The Grapes Ball” in Vršac. The wine offerings in Vojvodina comprises of the wine routes of Palić, Fruška Gora, and Vršac.

3.2. Wine Routes in Palić

In Palić, the entire region lies on sandy soil made after the disappearance of the prehistoric Pannonian Sea. Therefore, wines of this area are popularly called “sand wines”. Sandy terrain and a temperate continental climate are significant factors for the development of high-quality vines [

48]. The wine tradition of Subotica-Horgoš Sands is over 2000 years old. In Bačka, viniculture made its progress after the intrusion of phylloxera in Europe. At that time, three wine cellars in Palić, Čoka, and Biserno Ostrvo near Novi Bečej were founded, and they still make up the backbone of viniculture development in this area. Subotica-Horgoš Sands covers 24,000 ha, and almost all of its surface is suitable for vine growing. Vineyards are grouped around settlements in the municipalities of Kanjiža and Subotica.

This area has sandy soil and sporadic quicksand, then clay soil, chernozem with sand, and brown steppe soils. The terrain is either flat or wavy plateaus. The climate is typically continental, and due to the configuration of the terrain, the break of cold air during winter is also possible. Traditionally, certain old sorts of the vine are grown there. Earlier, that was Kadarka, and now it is Kevedinka, and Muskat Krokan in Novi Bečej. In new vineyards, it is Italian Riesling, Rhine Riesling, and Chardonnay [

47]. Recommended white wine sorts in this area are Italian Riesling, Župljanka, Burgundy White, and Ezerjó. There are famous white sorts in Čoka: Muscat Ottonel, Semillon, and Muscat Krokan from Biserno Ostrvo, and from the red sorts there are Merlot, Blaufränkisch, Pinot Noir, and Cabernet Sauvignon.

Sandy terrain, a temperate continental climate, and quality sorts of vine make very quaffable wines of harmonious taste, tender flavor, and drinking quality. Sommeliers skillfully recommend these wines with the traditional dishes of Vojvodina. Such a typical dish of this region, Hungarian Porkolt, is well paired with Merlot wine. Rooster stew goes well with Cabernet Sauvignon, and beef with mushrooms is well paired with Kadarka. “Vintage Days” is the event that characterizes this area and celebrates the festivity of grapes and wine. It is traditionally held in Palić in late September and represents a relevant potential of the Wine Route “Palić” [

16].

3.3. Wine Routes in Fruška Gora

Srem vineyards are one of the oldest vineyards in Europe. Vines have been grown here for thousands of years since the Roman Emperor Probus of Ancient Sirmium planted the first vine. After the Turkish occupation, viniculture was gradually renewed here, with its peak during Austrian–Hungarian rule. The wine has always been the status symbol of many people from Karlovac, and the quality of this product made it famous in Europe. For several centuries, Karlovci was considered a Serbian wine capital. The wines of Fruška Gora were exported in the Czech Republic and Poland as far as back as the 15th century. In 1783, the writer and a member of the Vienna Academy of Sciences, Zakarije Orfelin, was printing a publication called “Iskusni Podrumar”, and Prokopije Bolić, the archimandrite of the Rakovac Monastery in Fruška Gora, printed in 1816 the first vineyard manual named “Soveršen Vinodelac” in Budim [

16]. Bermet is the authentic wine of this region, which traders exported in the US 150 years ago, and according to certain data, Bermet was in the wine offerings of the “Titanic” [

16]. This is a special liqueur wine, similar to Italian Vermouth, but it is made in a different way, by maceration of more than 20 different herbs and spices. In this area, vineyards are located on the sloppy terrains, plateaus, and the slopes of Fruška Gora, and there are also favorable effects by the river Danube. The climate is continental and, in such conditions, the vegetation process of vine lasts for seven months, and the winter hibernation lasts for five. The autochthonous sorts Vranac and Portugieser, cultivated on the Fruška Gora mountain, were used for making Ausbruch and Bermet in the past, and the wines made from domestic crossed sorts are Župljanka (Prokupac and Pinot Noir), Neoplanta (Smederevka and Traminer Red), Sila (Kevedinka and Chardonnay), and Liza (Pinot Gris). The recommended sorts of grapes in this area are the Italian and Rhein Riesling, Traminer, Sauvignon, Neoplanta, Sirmium, and Župljanka.

Due to its geographical position, the proximity of the Danube, its microclimate, and the reflection of the sunshine on the surface of the Danube, the grapes soon become ripe and have one to two percent more sugar compared to other vineyard regions of Vojvodina. The most popular sorts of wine of this region are Fruška Gora Riesling, Italian Riesling, Rhine Riesling, Župljanka, Traminer, Bouvier, Blaufränkisch, Chasselas, Silvaner, Portugieser, and specific aromatized Bermet [

47]. There are more than 60 wine cellars in Fruška Gora. Bermet and Ausbruch are sweet, very strong and aromatic wines. “Neoplanta”, the authentic aromatized wine of this region can be found in a cellar in Čerević; and in the nearby villages of Neštin, Banoštor, Erdevik, and Irig there are many interesting wine cellars and wineries. Well-known wineries and wine cellars in this area are “Tomcat’s Wine Cellar”, “Vinum”, wine cellar “Kiš”, wine cellar “Dulka”, wine cellar “Roša”, wine cellar “Kosović”, wine cellar “Živanović”, winery “Kovačević”, winery “Urošević”, winery “Bononija”, and others. Bermet is still produced in Sremski Karlovci, and in some wineries, it can be tasted with a local sweet pie. Karlovac winemakers confirm that wine charts in the best restaurants cannot be made without the wines from their private cellars. Each year, in late September, there is the event in Karlovci, called “Grožđebal” (“The Grapes Ball”) which is dedicated to grape harvesting and wine [

16].

3.4. Wine Routes in Vršac

According to some historical sources, the viniculture in the region of Vršac dates back to the time of Dacians and Roman rule, and the first written information about this comes from the 15th century when the wine of Vršac was sold to the court of King Vladislav the Second in 1494. From a record of the Turkish travel writer Evliya Çelebi, it has been discovered that the slopes of Vršac Hill were planted with vines which have sweet and delicious grapes. In Banat, vineyards gained importance during the rule of Maria Theresa. In the late 19th century, there were more than 10,000 ha of vineyards in Vršac. These were the largest vineyards in the Austro–Hungarian Empire. With the expulsion of the Turks and the settlement of the Germans from the Rhineland, viniculture became the main economic branch. After the Second World War, instead of the expelled Germans, the Slovenes, Macedonians, then the colonists from Bosnia, Lika, Banija, and Kordun settled in the village. Due to this, there are 1500 inhabitants of 22 different nationalities today in this wine region of Vojvodina. Of 425 households, 80 maintain about 100 ha of vineyards, which, with the plantations of Vršac vineyards of about 1000 ha, makes this region a significant wine region in Serbia [

49].

The Vršac vineyards are spread on hilly terrains around Vršac, on the ending hillsides of the Carpathians. It consists of “Vršački Vinogradi” which has plantations with over 1700 ha of vineyards, while in the whole region there is about 2100 ha. The soil is sandy. The climate of this region is typically continental. Of the autochthonous and old sorts here are also Župljanka, Smederevka, Gutedel Weisser (Chasselas), and Kreaca. Kreaca is an old white sort of vine, while there are almost no red sorts. Favorable geographical and climate conditions for cultivating vine caused the inhabitants to opt for serious grape and wine production. Today, the entire region, where the Vršac Mountains caress the mild plains of Banat, is under vineyards and is one of the most significant vineyard regions in Serbia. Among the supreme and top-quality wines of this wine region, there are Muscat Ottonel, Chardonnay, Pinot Bianco, Rhine Riesling, and Italian Riesling, and also a very popular Banat Riesling from the sorts of Italian Riesling, Smederevka, Župljanka, and Kreaca. Wine facilities in this region are “Vršački Vinogradi”, winery “Krstov”, winery “Vinik”, “Selekta–Podrum Stojšić”, cellar “Nedin”, and others [

16,

47].

4. Results

In the questionnaire, young people were asked to rate the importance of a particular wine route in Vojvodina for the development of a tourist offer, by grades 1 to 5. The answers are shown in

Table 3.

From the data provided, it can be concluded that the respondents rated the importance of the wine routes in the tourist offer of Vojvodina with very high average ratings. Considering that these are the students who had the opportunity to visit the wine routes, their answers are of great importance. This indicates also the importance of these resources in tourism planning. Including these wine routes in the tourism offer would directly affect sustainable tourism development. These answers can also be tested by correlation with SPSS software (which is presented in

Table 4).

The next question was about their knowledge of the existence of wine routes in Vojvodina. Responses and correlations are represented in

Table 5;

Table 6.

Results show that the majority of students have knowledge of the existence of wine routes, in whole or in part. They were asked how the wine routes in Vojvodina are presented to foreign tourists. This question was asked in order to find out the ideas of young people. Additionally, this issue may relate to possible models of inclusion of Vojvodina wine routes in the tourism offer, and in what way it would be most appropriate to promote wine routes. Responses were given by the principle of Likert scale of 1 to 5, and shown in

Table 7, with correlation shown in

Table 8.

Respondents pointed directly to the importance of the existence of Vojvodina wine routes and recognized them as significant tourist potentials. Implementation of these wine routes into the tourist offer of both Vojvodina and Serbia would result in a significant increase in the number of domestic and foreign tourists. As a result, in addition to the positive socio-cultural benefits (events, folklore etc.), economic effects would be directly realized, both for members of the local community and for the state. It is also the basic principle of sustainable tourism development.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Wine tourism has a cultural connotation in its foundation, and includes the way of life of a particular people, and their attitude towards wine and food [

50]. This form of touristic fluctuations initiates the organization of many festivals dedicated to wine. It also has an educational and pedagogical character because it enables learning about different types of wine production technology, tasting, and recognition of certain qualities [

51]. Today, the element of public knowledge is matching wine with food, which is being taught in numerous sommelier schools. In the case of Vojvodina, wine tourism could be founded on wineries and wine events with the tasting of wine and homemade specialties [

16]. In the tourism market, there is a new kind of tourists whose priority is the visiting of wine regions. The visitors of wine regions are provided with a unique experience along with the opportunity of getting to know a certain vineyard region and its characteristics. Some wineries have already done much to improve their offers (for example, visiting vineyards, taking part in wine-growing and wine-making activities, visiting surrounding natural, cultural and historical localities etc.). It is necessary to properly plan and organize the wine tourism in order to relieve the main tourist seasons and to proportionately distribute the number of tourists throughout a whole year. It is also important for the state to recognize the benefits of wine tourism and to provide financial support, both to the country or the local community and the wineries willing to engage in wine tourism, and want to promote the destination in the world with the assistance of specific products such as wine. Visiting wineries within a wine tour is just one of the experiences visitors have during a visit to a destination, with special attention being paid to accommodation, restaurants, hospitality, the value of service, quality, and authenticity of attractions and other available tourist activities [

52], as well as the availability of information about the destination (maps, brochures, tourist documentation, etc.) [

53]. Wine tourism of Vojvodina can include a wide range of experiences for visitors, both from Autonomous Province of Vojvodina and Serbia, and from neighboring and other European countries, such as Romania, Hungary, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Austria, Germany, the Russian Federation, and other European and non-European countries.

The research conducted in this paper indicates that the development of tourism in Vojvodina can have very good economic and socio-cultural effects through the development of specific forms of tourism, among which wine tourism based on the creation of wine routes is distinguished. With this in mind, the proposal for further development of tourism in Vojvodina and future research is to create wine routes as a unique and specific tourism product. The suggestion is that the wine routes should be established on the basis of:

participation in grape harvesting and initial wine production;

gastronomic specialties by which Vojvodina is renowned;

becoming acquainted with the customs following the production of the vine, grape harvesting, and wine production;

learning about the making and production of wine;

learning about wine and food pairing;

learning about other cultures, customs, history, and other ethnographic and ethno-social values; and

economic, socio-economic, and ecological aspects of sustainable tourism development [

54].

The economic and sociocultural benefits of wine tourism would be:

increased number of domestic and foreign tourists, growth in demand for wine tourism as a specific tourism product [

55];

extended visits and consumption by tourists;

enlarging a destination;

increased demand for complementary forms of tourism (rural, gastronomic, event, hunting, and other forms of tourism);

keeping existing, and attracting new visitors [

56];

the extension of the tourist season; and

initiating new service and entertainment programs.

Overall, but especially with tourist perspectives, the findings show that wine routes are perceived to facilitate new knowledge and promote fast interactions with wine and cultural heritage. The wine routes offer, first of all, the opportunity to discover wine and cultural heritage, given the fact that the visitors can come into contact with those places he does not yet know, becoming familiarized with the value of the places he visits. At the same time, the visitors enjoy the excitement of being a part of the visited area. The Autonomous Province of Vojvodina has all the geographical and climate conditions required to make top-quality wine and grapes. At the moment, there are not enough wineries on the wine route to develop wine tourism and make Vojvodina a competitive wine tourism destination in the region. By strengthening overall wine potentials, sustainable tourism development would be directly improved [

57], through the integration of specific tourism products such as wine, wine cellars, wine events, and wine routes in general. Obviously, the study results are specific to a region and consequently, cannot be generalized, even because achievements usually depend on the involved stakeholders and especially the local governance. Nevertheless, the findings may be useful for local actors involved in the development of the wine tourism sector, apart from representing a starting point for further research dealing with future trends.