Abstract

Consumer participation typically reduces consumer skepticism and leads to a positive response to corporate social responsibility (CSR) activities. Although many companies are encouraging consumers to participate in CSR activities, there is still insufficient research on the effectiveness of this strategy. That is, prior studies do not provide guidelines on the effectiveness of requiring consumers to participate in CSR activities. We examine the impact of the required participation effort on CSR participation intention, focusing on the differences in consumers’ perception of a warm glow feeling and costs according to their construal level. For this study, 107 participants were recruited using Amazon Mechanical Turk. We tested hypotheses using a 2 (CSR participation effort) × 2 (construal level) between-subject analysis of variance (ANOVA), planned contrast analysis, and mediation analysis. The results indicate that for consumers with high construal levels who perceive participation efforts as warm glow, participation efforts have a positive impact on CSR participation intention. However, for those with low construal levels who perceive participation efforts as costs, high required efforts have a negative impact on their participation intention. Finally, we discuss the implications of these results, discuss the limitations, and suggest future research directions.

1. Introduction

Engaging consumers in marketing activities is an effective strategy to elicit positive responses from consumers [1,2]. Companies can interact with consumers through their engagement, which can increase their satisfaction or loyalty [3,4]. For this reason, companies are adopting tactics to induce consumer engagement in various areas, which they extend to their use of strategies to achieve corporate sustainability goals, such as corporate social responsibility (CSR) [5,6]. For example, Coca-Cola encouraged consumers to participate in the “A World Without Waste” campaign, which aims to collect and recycle 100% of soda cans and plastic bottles by 2030 [7]. In China, Coca-Cola ran its “VenCycling” program. VenCycling is a compound word of vending machine and recycling that allows consumers to recycle through vending machines. Consumers can earn points by recycling, which they can then use to send e-vouchers to friends or to purchase items made from recycled plastic [8]. Similarly, Hyundai Motor Group conducted a gift car campaign to present cars to underprivileged families when web posts received more than 100 consumer comments. This is an example of CSR activities based on active communication with consumers [9]. In addition, Walmart and Sam’s Club adopted the “Fight Hunger. Spark Change” campaign, which sponsors hungry children based on consumer participation, thereby raising consumer awareness of social issues [10].

Although companies are encouraging consumer participation in their CSR activities in several ways, there is a lack of academic interest in this area [11]. In particular, while companies are asking consumers for different levels of participation effort, it is difficult to find out which level of participation effort is the most appropriate for successful CSR [12]. Previous study shows that the required effort has both positive and negative effects on consumer responses [11]. According to Howie et al. [11], efforts required for consumers may be perceived as benefits such as happiness and self-esteem enhancement or as costs such as physical effort and cognitive dissonance. However, they focused mainly on the negative impacts of the effort, and did not empirically examine when the effort was considered positive or negative. As a result, previous studies do not provide clear guidelines for setting an effective level of effort for companies. To provide more meaningful and practical guidelines, this study examines the effect of the required level of participation effort on consumers’ CSR participation intention.

Previous studies show that consumer effort and monetary contributions to CSR may be perceived as providing benefits or as imposing related costs. The perceived benefits relate to the altruistic emotion that comes from pro-social behavior. Consumers view themselves as good people by helping others and experience happiness. The perceived costs, on the other hand, are associated with the non-monetary/monetary losses required for pro-social behavior. The costs incurred in participating in the CSR make consumers experience dissonance and reduce participation costs [11,13]. Based on previous findings, we suggest two opposing roles of CSR participation: the provision of benefits such as a warm glow feeling and monetary or non-monetary costs.

Furthermore, this study also introduces a moderating variable that can influence consumer’s reaction to the required participation effort. Specifically, we adopt construal level theory which is related to the way people interpret objects or events to examine when and how participation effort activates each role of warm glow or costs. Prior research [14,15] from the construal-level perspective demonstrates that high construal levels allow consumers to concentrate on benefits such as the purpose or value of the behavior and the quality of the target, while low construal level induces consumers to focus on the means of behavior, feasibility, and the costs associated with obtaining the target. Thus, we focus on the difference in consumer perception by construal level type in the context of participation in CSR. Specifically, we expect people with high construal level to perceive participation efforts as providing a warm glow, but those with low construal level to recognize participation efforts as costs.

The purpose of this study is to investigate how the participation effort required by CSR is perceived by consumers and to examine factors affecting the participation intention. Specifically, first, we examine the effect of participation efforts in CSR on consumer responses. Although participation effort has positive and negative sides, prior studies do not fully clarify the role of participation effort. We present two opposing roles of participation effort: providing warm glow and incurring costs. In other words, we investigate the mechanism of influence of the level of participation effort on CSR participation intention. Second, we examine when and how the roles of participation efforts were activated by studying the moderating role of construal level. We predict that high construal level makes consumers feel warmer glow and increases their intention to participate in CSR, but low construal level makes consumers perceive high costs and lower their intention. We expect that the results will extend extant studies on CSR and provide effective practical implications for implementing CSR strategies using consumer participation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses

2.1.1. Consumer Participation in Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR)

CSR is more than a company’s legal liability. It is the company’s voluntary pro-social activities to achieve sustainable development [5]. Previous research suggests that a company’s CSR activities not only lead to positive product evaluations, brand evaluations, and purchase intention from consumers, but also increase a company’s market value [16,17,18]. For example, Sen and Bhattacharya [19] show that CSR activities have a positive impact on consumer evaluations of a company because CSR activities increase their perceived congruence with the company. Perceived congruence strengthens as consumers’ support for CSR activities increases. Luo and Bhattacharya [20] state that CSR activities have a positive influence on consumer satisfaction and a company’s market value. Companies that conduct social activities not only elicit positive responses from consumers, but also improve their market performance by securing moral justification. The higher the company’s ability, such as product quality or innovation capacity, the greater is the positive effect of CSR.

However, CSR activities can negatively affect consumer responses because consumers may doubt the company’s motivation for CSR activities. Yoon et al. [18] show that when consumers perceive a company’s CSR activities as hypocritical, their evaluations change more negatively than before receiving CSR-related information. Yoo and Lee [21] also suggest that the impact of CSR on company evaluation depends on the consumer’s perception of the CSR motivation. In other words, if consumers think that the company conducts CSR activities for good reasons, then their evaluations are positive; however, if they perceive the company’s motives negatively, then their evaluations toward the company become negative. Thus, companies are now trying to find ways to elicit positive responses by reducing consumer skepticism about the authenticity of its CSR activities.

Prior research suggests that consumer participation in CSR, which encourages consumer engagement in CSR activities, can have a positive effect on consumer perceptions of corporate motivations [22,23,24]. That is, consumer perceptions of the authenticity of the company performing the activities is important for successful CSR [11,25]. Consumer participation in CSR allows them to feel high authenticity and trust in corporate activities [24]. From the marketing perspective, companies use consumer participation as an effective strategic tool to drive positive consumer responses. Prior research demonstrates that companies can enhance satisfaction, trust, and loyalty by engaging consumers in production process [4,22,26]. In addition, consumer participation in CSR can lead to more positive responses by increasing their identification with the CSR activities compared to general CSR activities [5,27]. In summary, consumer participation in public campaigns has positive effects on their perceptions of the authenticity of the company’s activities. According to previous studies, transparency is one of the most important factors influencing consumer’s perception of authenticity about corporate activities [28]. In other words, in order to raise consumers’ awareness of authenticity, clear and sufficient information regarding the decision-making process of the company should be provided to consumers. At this time, consumer participation can make consumers committed to the company’s decision making process by increasing transparency and authenticity [28]. Thus, consumers who participate in CSR truly believe in and do not doubt corporate motivation for CSR activities. As a result, consumers have positive evaluations and commitment toward the companies.

2.1.2. Level of Participation Effort

Participation effort refers to the degree to which consumers put efforts and resources into a production process [26]. Following prior works, we define participation effort as the degree of effort and resource input required from consumers to participate in companies’ CSR activities. The required participation effort is an important variable that influences consumers’ participation intention in CSR and their perception of CSR motivation [11,13]. However, previous studies reveal both positive and negative effects of participation effort on consumer responses because customers can perceive two opposing meanings: a warm glow feeling or a cost [11,13]. Warm glow refers to the moral satisfaction that consumers earn from carrying out pro-social behaviors, such as CSR participation, or by making donations [29,30,31], while the perceived costs represent the monetary and non-monetary costs such as money, time, and effort required to participate in CSR activities [32,33,34].

Previous studies identify a differential effect of perceived warm glow and costs on consumers’ participation intention, depending on the level of consumer participation. Habel et al. [13] find that if consumers perceive the level of effort required to participate in CSR as warm glow, then they think that their pro-social behaviors can contribute to society. Consequently, the higher the level of effort, the more positive the consumers’ response to CSR. However, if consumers perceive the level of effort as a cost, then they recognize their participation as a sacrifice and react negatively to CSR. Similarly, Howie et al. [11] suggest that consumers have positive CSR participation intention if they perceive that the effort required for CSR participation as benefits, such as warm glow, whereas they have a negative intention to participate if they construed the effort as costs.

Therefore, it is important for companies to understand whether customers construe the required participation effort as a warm glow feeling or costs for successful CSR. In this study, we examine this differing effect in terms of the construal level.

2.1.3. Construal Level

According to construal level theory, people interpret events differently and make dissimilar decisions depending on their (high or low) construal level [35,36]. Specifically, the people with a high construal level have abstract, global, and primary thinking (i.e., thinking about the central aspects) focused on events, while those with a low construal level interpret events through specific, local, and secondary thinking (i.e., thinking about the incidental aspects) [35,36].

The difference in construal level also affects how people view their goals. We can classify goals by desirability and feasibility [14,15]. Desirability refers to the value of the goal; that is, the reason to achieve the goal, and it is related to the high construal level. Such individuals consider the “why” of the behavior and what value they can gain by achieving the goal. In contrast, feasibility is related to how easy the goal is to achieve and is related to the low construal level. Such individuals account for how to act to achieve the goal [14,15]. For example, according to Hsee and Weber [37], the amount of money earned by gambling may be regarded as the desirability aspect, which corresponds to the goal and value of gambling, while the probability of obtaining it is related to the feasibility aspect, which is the difficulty of obtaining the amount. Thus, when people choose one of the two alternatives (e.g., [$800, 100%] vs. [$2000, 50%]), they choose the alternative with the highest probability of acquisition ([$800, 100%]). However, when they predict others’ choices, they expect others to choose the higher acquisition amount alternative ([$ 2000, 50%]). This is because people focus more on the feasibility of their own choice, where social distance is near, but they are more likely to focus on desirability when they predict the choices of others in which social distance is distant. In other words, consumers with high construal tend to concentrate on what they obtain by gaining the objects or value of the goal, while consumers with low construal tend to focus on how to achieve the goal or acquire the objects. Indeed, Trope, Liberman, and Wakslak [38] show that the benefits or quality of product acquisition relate to the high construal level, whereas the costs paid for the acquisition of a product relate to the low construal level. Bornemann and Homburg [39] find differences in how people perceive prices by their construal level. Specifically, people with high construal levels tend to value the benefits they can ultimately gain through the product. Therefore, they are likely to perceive price as quality; that is, the higher the price, the higher the perceived quality of the product. However, people with a low construal level tend to value the monetary costs of buying or using the products. That is, they perceive that the higher the price, the higher the monetary costs of the product.

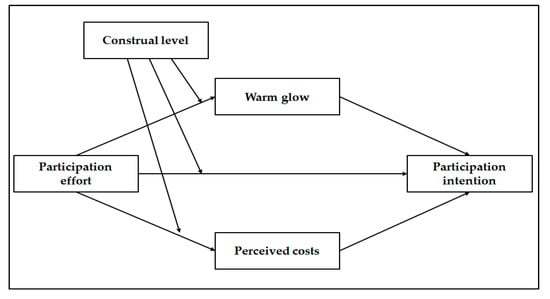

Applying these prior findings to the context of CSR participation, we expect that consumers with a higher construal level who focus on the goals or values of behavior will perceive higher a warm glow feeling as the level of participation required increases. Therefore, they will have positive CSR participation intention when participation requires a high amount of effort than when the effort required is low. In contrast, we expect that consumers of low construal levels who focus on feasibility in the acquisition process will perceive higher costs as the level of participation required increases, and therefore have negative intentions to participate in CSR as the level of participation required increases. Based on the above discussion, we propose the following hypotheses and present the research framework in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model.

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

(a) Consumers with high construal level will perceive higher warm glow when the required level of CSR participation effort is high than when it is low. However, (b) for consumers with low construal level, there will be no difference in warm glow according to the required level of CSR participation effort.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

(a) For consumers with high construal level, there will be no difference in perceived costs according to the required level of CSR participation effort. However, (b) consumers with low construal level will perceive higher costs when the required level of CSR participation effort is high than when it is low.

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

(a) Consumers with high construal level will have more positive participation intention in CSR when the required level of CSR participation effort is high than when it is low. However, (b) consumers with low construal level will have more positive participation intention in CSR when the required level of CSR participation effort is low than when it is high.

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

Warm glow and perceived costs mediate the effects of the required level of participation effort and construal level on CSR participation.

2.2. Methodology

2.2.1. Data Collection and Sample

We recruited 107 U.S. residents from Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk) in exchange for monetary compensation and assigned each participant randomly to each of the four conditions. According to previous studies, participants recruited by MTurk are demographically diverse and representative [40,41] than samples collected by traditional methods or the Internet. Prior studies mentioned MTurk as an appropriate tool for conducting psychology and social sciences research. We conducted the surveys on 12 August 2019 and 18 August 2019. After deleting 4 participants with missing information, we used 103 for the analysis. The sample size for each group was 25–27. The participants included 59 males (57.3%) with an average age of 36.68 (SD = 10.73, range = 20–67) (Table 1). Although the size of the sample used in the experiment is rather small, this size exceeds the standard quantity suggested in the previous study (15–20 subjects per independent variable) [42]. Thus, sample size is sufficient for analysis in this study, and issues related to sample size are mitigated [43].

Table 1.

Sample characteristics.

2.2.2. Development of Experimental Stimuli

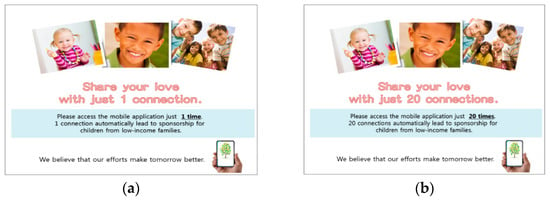

We conducted a pretest with 42 participants to determine the level of participation effort, which we manipulated with the required number of accessing applications based on prior research [11]. We set the required number of accessing applications for the low participation effort condition as 1 and set it as 20 for the high participation effort condition. The scenario was presented to the participants, who were asked to respond to the required participation effort for campaign participation. We measured participation effort on a 7-point Likert scale for a single item (I need to put a lot of effort into participating in this campaign), as in existing studies [44]. Participants perceived a high participation effort for the 20 connections condition (M = 5.36) compared to the 1 connection condition (M = 3.90; t = 2.506, p < 0.05). Thus, the results of the pretest indicate that the manipulation of high/low participation effort was successful.

2.2.3. Methods

We used a 2 (CSR participation effort: high vs. low) × 2 (construal level: high vs. low) between-subject factorial design. The subjects who participated in the experiment performed two different tasks. First, they performed a construal level related task. We primed the participants’ construal level following methods used in prior research [45,46]. Specifically, we presented participants with a specific set of words (e.g., dog, singer, king, pasta, etc.) and asked them to associate different words according to construal level priming conditions. In the high construal level condition, participants were asked to write down the words that corresponded to the superordinate categories of suggested words. For example, when the word “dog” is presented, participants associate and write words such as “pet”, the upper category of dog. On the other hand, in the low construal level condition, participants were asked to write down the words that correspond to the sub-examples of the words presented. For example, when the word “dog” is presented, they associate and write words such as “poodle”, the sub-exemplar of dog. After the task, participants responded to manipulation check items about the construal level, which we performed using a Behavioral Intention Form (BIF) [47]. The BIF consists of 25 items. Each item consists of an action and two descriptions of the action. The purpose of action (e.g., locking a door) is related to the high construal level (e.g., locking the house) and the process is related to the low construal level (e.g., putting a key in the lock). We asked participants to select a description that they judged appropriate for the suggested action. We coded zero when participants selected the goal description and one when they chose the process description. The BIF scores range from 0–25 with high scores representing high construal levels, and vice versa.

Next, we exposed participants to the stimulus containing the participation effort. The experimental stimulus (see Appendix A) contains a message that they can donate to children from low-income families by accessing the application (1 connection vs. 20 connections). Afterwards, participants responded to questions related to the perceived effort (manipulation check items for participation effort), warm glow feeling, perceived costs, and participation intention. Finally, the participants completed the demographic questions.

2.2.4. Measures

As mentioned earlier, we measured construal level using a BIF consisting of 25 items based on prior studies [47].

The level of participation effort refers to the degree of effort required to participate in the campaign, which we measured using three items (Cronbach’s α = 0.930) adopted from Xia et al. [44]. We measured warm glow feeling with five items (Cronbach’s α = 0.942) based on Apaolaza and D’Souza [48] and Västfjäll, Slovic, and Mayorga [49]. We measured perceived costs with two items (Cronbach’s α = 0.922) based on Bridger and Wood [50]. Participant intention is the intention to participate in the CSR campaign, which we measured using four items (Cronbach’s α = 0.917) suggested in prior research [51]. We measured all items on a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” Table 2 lists the survey items used to measure the variables.

Table 2.

Variables and measurement items.

3. Results

3.1. Manipulation Check

The analysis of variance (ANOVA) test with the BIF score as the dependent variable revealed a significant effect of construal level (F = 6.206, p < 0.05). The BIF score was higher for the high construal level participants (M = 16.04) than for the low construal level participants (M = 13.46). The effects of the other variables were not significant (all, p > 0.1). The ANOVA results with perceived effort as the dependent variable show a significant main effect of participation level (F = 12.031, p < 0.01). Participants in the high participation condition (M = 4.51) reported that they needed more effort to participate in the campaign compared with those in the low participation condition (M = 3.41). The influence of the other variables on the perceived effort was not significant (all, p > 0.1). Therefore, the manipulation of construal level and participation effort was successful.

3.2. Model 1: Participation Effort on Warm Glow and Costs, the Moderating Role of Construal Level

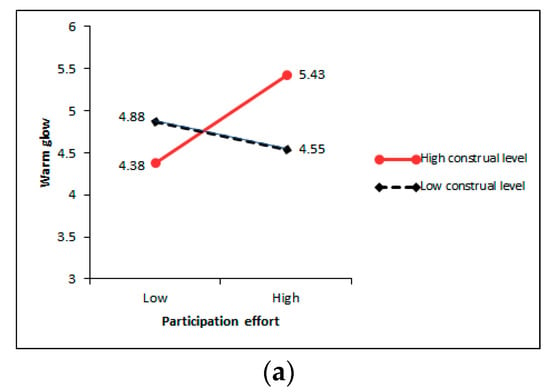

The ANOVA results indicate no significant main effects of CSR participation effort and construal level on warm glow feeling (all, p > 0.1) (see Table 3). However, the two-way interaction between participation effort and construal level is significant (F = 7.787, p < 0.01). The follow-up planned contrasts analysis reveals no significant difference in warm glow by the level of CSR participation effort (high vs. low participation effort: 4.55 vs. 4.88; F = 0.920, p > 0.1) for participants with low construal levels. However, participants with high construal levels felt more warm glow when the participation effort was high (M = 5.43) than when participation effort was low (M = 4.38; F = 8.868, p < 0.01) (see Figure 2). Thus, the results support Hypothesis 1.

Table 3.

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) results: warm glow.

Figure 2.

Interaction effects on (a) warm glow and (b) perceived costs.

The ANOVA results for perceived costs show a significant main effect of participation effort (F = 14.082, p < 0.001) (see Table 4), indicating that participants perceived higher costs of CSR participation when the level of required effort was high (M = 4.75) than when it was low (M = 3.59). However, the effect of construal level was not statistically significant (F = 0.617, p > 0.1). More interestingly, the two-way interaction between participation effort and construal level was significant (F = 7.787, p < 0.01). The follow-up contrast analysis shows that the perceived costs of participation effort was not significant for high construal level participants (high vs. low participation effort: 4.46 vs. 4.02; F = 1.008, p > 0.1). Low construal level participants, on the other hand, perceived higher CSR participation costs when participation effort was high (M = 5.02) than when it was low (M = 3.14; F = 18.647, p < 0.001) (see Figure 2). These results support Hypothesis 2.

Table 4.

ANOVA results: perceived costs.

3.3. Model 2: Participation Effort on Participation Intention, the Moderating Role of Construal Level

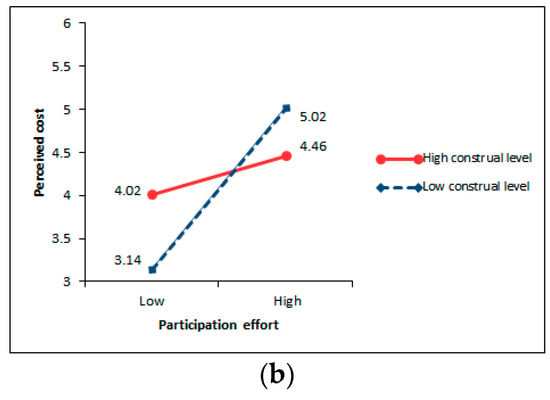

The ANOVA results for the effect of participation effort and construal level on CSR participation intention indicates a marginally significant main effect of construal level (high vs. low construal level: 4.88 vs. 4.42; F = 3.470, p = 0.065) (see Table 5). More importantly, we found a significant two-way interaction between the participation effort and construal level variables (F = 11.601, p < 0.05). The contrast analysis shows that participation intention for participants with high construal level was more positive when the required CSR participation effort was high (M = 5.32) than when it was low (M = 4.46; F = 6.070, p < 0.05. In contrast, participation intention was more positive when the participation effort was low (M = 4.84) than when it was high (M = 4.03; F = 5.535, p < 0.05) for participants with low construal level (see Figure 3). These results also support Hypothesis 3.

Table 5.

ANOVA results: participation intention.

Figure 3.

Interaction effects on participation intention.

3.4. Model 3: Participation Effort and Participation Intention, the Mediating Role of Warm Glow and Perceived Costs, and the Moderating Role of Construal Level

We performed a bootstrap analysis with 10,000 resamples for the mediation analysis (model 4 in PROCESS macro; see Table 6) [52,53]. First, in the high construal level condition, we find a significant indirect effect via warm glow (participation effort → warm glow → participation intention; indirect effect = 0.72, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.2646 ~ 1.4348). The indirect effect via perceived costs (participation effort →perceived costs → participation intention) was not significant (indirect effect = 0.00, 95% CI: −0.0814 ~ 0.1701). Second, in the low construal level condition, the indirect effect via perceived costs (participation effort → perceived costs → participation intention) was significant (indirect effect = −0.62, 95% CI: −1.2355 ~ −0.2573), whereas the indirect effect via warm glow (indirect effect = −0.18, 95% CI: −0.7567 ~ 0.1893) was insignificant (participation effort → warm glow → participation intention).

Table 6.

Mediation analysis results.

These results mean that consumers with high construal levels show positive (negative) CSR participation intention by warm glow (costs) rather than costs (warm glow). This means that Hypothesis 4 is supported.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

4.1. Summary of Findings and Implications

Interest in consumer participation in CSR activities is increasing. It is becoming more important to examine consumers’ required effort level to participate in CSR activities for more successful CSR. This study investigates the effects of required participation effort on CSR participation and the moderating role of construal level in this relationship. In addition, we examine the mediating role of warm glow and perceived costs. Our results from the experiments empirically support the proposed model and hypotheses, and lead to several important findings.

We find that consumers’ participation effort in CSR has two roles: to provide warm glow and to impose perceived costs. Consumer participation intention was significantly different depending on the role they perceive in their participation efforts. In addition, we demonstrate that construal level influences the role of the perceived participation efforts. Specifically, a high construal level caused consumers to perceive the participation effort as warm glow. Thus, the higher the level of participation effort required from consumers in the CSR campaign, the more positive the intention to participate in CSR. In contrast, consumers with low construal level perceived the participation efforts as costs; that is, as the participation effort increased, their intention to participate decreased. These results support all hypotheses (H1–H4).

This study has several academic implications. First, although many companies are engaging consumers in their social activities, there is a lack of related research. We contribute to CSR and consumer participation research by examining the role of participation effort on consumers’ responses to CSR. For consumers with high construal level, warm glow mediates the effect of participation effort on participation intention, while for those with low construal level, perceived costs mediate the effect. These findings are in line with Howie et al. [12], who suggest that participation effort has both positive and negative impacts. However, we extend Howie et al. [12] by directly examining the mediating effects of warm glow and costs, thereby revealing the mechanism of participation effort. Finally, we confirm when consumers perceive participation effort as warm glow or a cost; that is, we find the moderating effect of construal level. Previous studies show that construal level affects consumer perceptions of gains and losses [36] or perceptions of price information [37]. Additionally, we demonstrate the strong influence of construal level on consumer perceptions of participation in CSR. In other words, we extend construal level theory by applying it to the CSR domain.

This study also has several practical implications. First, the results suggest that companies should reflect the target consumer’s characteristics when designing the level of required participation effort. Consumers do not always have similar psychological responses to the same required participation effort. If the target consumer perceives the level of participation effort in the campaign as a cost, it will have a negative impact on their perceptions of the campaign. Therefore, marketers need to consider the characteristics of the target consumers of the campaign when determining the degree of consumer participation in CSR activities. The level of participation effort is considered to be a relatively easy variable to control compared to other marketing variables related to CSR activities. Second, if companies want to increase consumers’ participation effort levels in CSR activities, they should activate a higher construal level among them; that is, companies’ strategies should focus on activating construal levels at a higher level so consumers focus on the warm glow feeling rather than the costs. Third, previous research shows that not only psychological distances such as temporal, spatial, and social distance, but also variables such as mood [54] and self-construal [55] influence construal level. In other words, consumer’s construal levels tend to be higher when psychological distance is far, they have a positive mood, and when their self-construal is independent. Based on the results of this study and previous studies, companies can develop various strategies to improve their CSR campaigns.

4.2. Limitations and Future Research

This study has several limitations that future studies can address. First, this study presented the level of participation effort in CSR to participants via access through a mobile application. However, companies actually encourage consumer participation in CSR campaigns in a variety of ways. For example, Seoul Metro and a private hospital jointly launched a CSR campaign to engage consumers by conducting CSR campaigns such that donations to vulnerable groups occur automatically when citizens use stairs in certain areas [56]. Therefore, future studies would be needed to adopt various types of CSR participation such as, walking, recycling, commenting in addition to clicking, to generalize our findings.

Another limitation of this study is that it measures behavioral intention, not actual behavior. Future research needs to investigate actual participation behavior instead of behavioral intention.

Third, support for low-income children used as a stimulus in this study is CSR activities related to the social cause. Since companies are implementing various CSR activities [19,57,58] in different fields, future research is needed to replicate the results of this study using other types of CSR campaigns, such as environmental protection, animal protection and cultural property preservation as experimental stimuli.

Finally, this study demonstrates that consumers can perceive their participation in CSR as either providing warm glow or incurring costs, and that this perception depends on their construal level. We focused on the mechanisms of consumer participation and the moderating role of variables in their perceptions. Based on these findings, we expect that future studies can adopt a different perspective. For example, the results of this study show that consumer perceptions of costs are negatively related to their participation intention. Future studies that examine the factors that could lower consumer perceptions of costs would provide companies with more practical implications.

Author Contributions

For Y.A. and J.L. conceived and designed the research. Y.A. collected and analyzed data. J.L. elaborated research model and hypotheses. All authors have read and agree to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Experiment stimuli (a) low-participation effort and (b) high-participation effort.

References

- Ashley, C.; Tuten, T. Creative strategies in social media marketing: An exploratory study of branded social content and consumer engagement. Psychol. Mark. 2015, 32, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woisetschläger, D.M.; Hartleb, V.; Blut, M. How to make brand communities work: Antecedents and consequences of consumer participation. J. Relatsh. Mark. 2008, 7, 237–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barger, V.; Peltier, J.W.; Schultz, D.E. Social media and consumer engagement: A review and research agenda. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2016, 10, 268–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivek, S.D.; Beatty, S.E.; Morgan, R.M. Customer engagement: Exploring customer relationships beyond purchase. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2012, 20, 122–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sana-ur, R.; Beise-Zee, R. Corporate social responsibility or cause-related marketing? The role of cause specificity of CSR. J. Consum. Mark. 2011, 28, 27–39. [Google Scholar]

- Zasuwa, G. The role of company-cause fit and company involvement in consumer responses to CSR initiatives: A meta-analytic review. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moye, J. A World Without Waste: Coca-Cola Announces Ambitious Sustainable Packaging Goal. Coca Cola, 19 January 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Jed, E. Coke Machine In China Uses Facial Recognition To Dispense Drinks, Reward Recycling. Vending Times Out, 1 October 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Group, H.M. Launching the 5th gift car donation campaign. Hyundai Motor Group, 8 August 2014. [Google Scholar]

- CREEK, B. Fight Hunger. Spark Change. Here’s how…. PRNewswire, 9 May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Howie, K.M.; Yang, L.; Vitell, S.J.; Bush, V.; Vorhies, D. Consumer participation in cause-related marketing: An examination of effort demands and defensive denial. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 147, 679–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kneebone, S.; Fielding, K.; Smith, L. It’s what you do and where you do it: Perceived similarity in household water saving behaviours. J. Environ. Psychol. 2018, 55, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habel, J.; Schons, L.M.; Alavi, S.; Wieseke, J. Warm glow or extra charge? The ambivalent effect of corporate social responsibility activities on customers’ perceived price fairness. J. Mark. 2016, 80, 84–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trope, Y.; Liberman, N. Construal-level theory of psychological distance. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 117, 440–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ülkümen, G.; Cheema, A. Framing goals to influence personal savings: The role of specificity and construal level. J. Mark. Res. 2011, 48, 958–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, J.; Dawar, N. Corporate social responsibility and consumers’ attributions and brand evaluations in a product–harm crisis. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2004, 21, 203–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lii, Y.-S.; Lee, M. Doing right leads to doing well: When the type of CSR and reputation interact to affect consumer evaluations of the firm. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 105, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Y.; Gürhan-Canli, Z.; Schwarz, N. The effect of corporate social responsibility (CSR) activities on companies with bad reputations. J. Consum. Psychol. 2006, 16, 377–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, S.; Bhattacharya, C.B. Does doing good always lead to doing better? Consumer reactions to corporate social responsibility. J. Mark. Res. 2001, 38, 225–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Bhattacharya, C.B. Corporate social responsibility, customer satisfaction, and market value. J. Mark. 2006, 70, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, D.; Lee, J. The effects of corporate social responsibility (CSR) fit and CSR consistency on company evaluation: The role of CSR support. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodie, R.J.; Hollebeek, L.D.; Jurić, B.; Ilić, A. Customer engagement: Conceptual domain, fundamental propositions, and implications for research. J. Serv. Res. 2011, 14, 252–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollebeek, L. Exploring customer brand engagement: Definition and themes. J. Strateg. Mark. 2011, 19, 555–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvis, W.; Ouschan, R.; Burton, H.J.; Soutar, G.; O’Brien, I.M. Customer engagement in CSR: A utility theory model with moderating variables. J. Serv. Theory Pract. 2017, 27, 833–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhouti, S.; Johnson, C.M.; Holloway, B.B. Corporate social responsibility authenticity: Investigating its antecedents and outcomes. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 1242–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apenes Solem, B.A. Influences of customer participation and customer brand engagement on brand loyalty. J. Consum. Mark. 2016, 33, 332–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, A.; Rice, D.H. The impact of perceptual congruence on the effectiveness of cause-related marketing campaigns. J. Consum. Psychol. 2015, 25, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Men, L.R.; Tsai, W.-H.S. Perceptual, attitudinal, and behavioral outcomes of organization–public engagement on corporate social networking sites. J. Public Relat. Res. 2014, 26, 417–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, I.; Urminsky, O. When should the ask be a nudge? The effect of default amounts on charitable donations. J. Mark. Res. 2016, 53, 829–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strahilevitz, M.; Myers, J.G. Donations to charity as purchase incentives: How well they work may depend on what you are trying to sell. J. Consum. Res. 1998, 24, 434–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winterich, K.P.; Barone, M.J. Warm glow or cold, hard cash? Social identity effects on consumer choice for donation versus discount promotions. J. Mark. Res. 2011, 48, 855–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morewedge, C.K.; Holtzman, L.; Epley, N. Unfixed resources: Perceived costs, consumption, and the accessible account effect. J. Consum. Res. 2007, 34, 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morwitz, V.G.; Greenleaf, E.A.; Johnson, E.J. Divide and prosper: Consumers’ reactions to partitioned prices. J. Mark. Res. 1998, 35, 453–463. [Google Scholar]

- Staelin, R. The effects of consumer education on consumer product safety behavior. J. Consum. Res. 1978, 5, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberman, N.; Trope, Y. The role of feasibility and desirability considerations in near and distant future decisions: A test of temporal construal theory. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 75, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberman, N.; Trope, Y.; Wakslak, C. Construal level theory and consumer behavior. J. Consum. Psychol. 2007, 17, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsee, C.K.; Weber, E.U. A fundamental prediction error: Self–others discrepancies in risk preference. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 1997, 126, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trope, Y.; Liberman, N.; Wakslak, C. Construal levels and psychological distance: Effects on representation, prediction, evaluation, and behavior. J. Consum. Psychol. 2007, 17, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornemann, T.; Homburg, C. Psychological distance and the dual role of price. J. Consum. Res. 2011, 38, 490–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhrmester, M.; Kwang, T.; Gosling, S.D. Amazon’s Mechanical Turk: A new source of inexpensive, yet high-quality data? Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2016, 6, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paolacci, G.; Chandler, J. Inside the Turk: Understanding Mechanical Turk as a participant pool. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 23, 184–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1998; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Cowan, K.; Kinley, T. Green spirit: Consumer empathies for green apparel. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2014, 38, 493–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, L.; Kukar-Kinney, M.; Monroe, K.B. Effects of consumers’ efforts on price and promotion fairness perceptions. J. Retail. 2010, 86, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, K.; Trope, Y.; Liberman, N.; Levin-Sagi, M. Construal levels and self-control. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 90, 351–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Hong, J.; Zhou, R. How long did I wait? The effect of construal levels on consumers’ wait duration judgments. J. Consum. Res. 2017, 45, 169–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallacher, R.R.; Wegner, D.M. Levels of personal agency: Individual variation in action identification. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 57, 660–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, P.; Eisend, M.; Apaolaza, V.; D’Souza, C. Warm glow vs. altruistic values: How important is intrinsic emotional reward in proenvironmental behavior? J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 52, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Västfjäll, D.; Slovic, P.; Mayorga, M. Pseudoinefficacy: Negative feelings from children who cannot be helped reduce warm glow for children who can be helped. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 616. [Google Scholar]

- Bridger, E.K.; Wood, A. Gratitude mediates consumer responses to marketing communications. Eur. J. Mark. 2017, 51, 44–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grau, S.L.; Folse, J.A.G. Cause-related marketing (CRM): The influence of donation proximity and message-framing cues on the less-involved consumer. J. Advert. 2007, 36, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Lynch, J.G., Jr.; Chen, Q. Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and truths about mediation analysis. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 37, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labroo, A.A.; Patrick, V.M. Psychological distancing: Why happiness helps you see the big picture. J. Consum. Res. 2008, 35, 800–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spassova, G.; Lee, A.Y. Looking into the future: A match between self-view and temporal distance. J. Consum. Res. 2013, 40, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hankyoreh. More “donation and health staircases” coming to Seoul. Hankyoreh, 15 January 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya, C.B.; Sen, S. Doing better at doing good: When, why, and how consumers respond to corporate social initiatives. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2004, 47, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, X.; Heo, K. Consumer responses to corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives: Examining the role of brand-cause fit in cause-related marketing. J. Advert. 2007, 36, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).