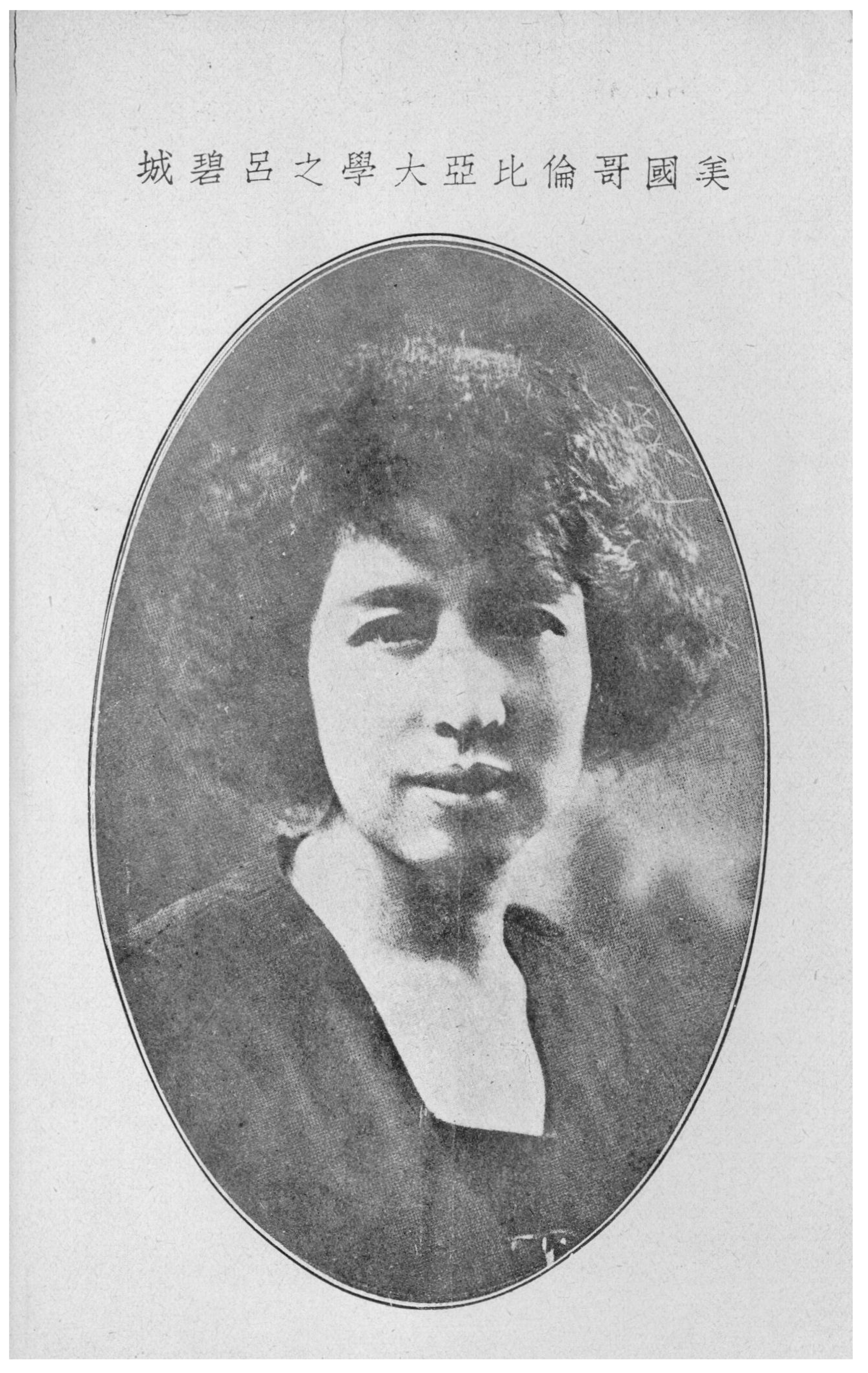

Seeking the Dharma on the World Stage: Lü Bicheng and the Revival of Buddhism in the Early Twentieth Century

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Lü Bicheng and British Psychical Research

The Society for Psychical Research in London was created in 1882. Its current address is 31 Tavistock Square, London. I have exchanged letters with them. The society is in the charge of renowned scholars and professors, who have produced numerous publications. They have invited me to join them. But I am about to convert to Buddhism and hope to achieve enlightenment. I intend to abide by Buddhist precepts and am not interested in investigating mysterious things. For these reasons, I have stopped contacting the society. But I am not against it either. In Europe, previous famous psychic mediums, such as M. Home and Eusapia Paladino, have achieved remarkable success. Although Browning mocked them in a poem entitled “Mr. Sludge the Medium,” no fraudulent behavior has been found. Last winter, the American psychic Dr. Grandon and his wife visited London, which attracted great attention. On December 6, the Daily Mail in Paris published an editorial, demanding that Dr. Grandon perform his experiment in public. People from the fields of science and psychical research gathered and paid close attention [to Dr. Grandon] in order to uncover the truth. They considered this to be the most relevant to the evolution of the world and people’s view of life.17

倫敦自一八八二年即有靈學會 (The Society for Psychical Research) 之設,現時地址為31, Tavistock Square London. 記者曾與一度通函,知其中主持者,多學界巨子、大學教授等,刊品甚豐。承其邀請入會,惟記者旋皈佛法, 只欲明心見性,勉持戒律,其他詭異之事則不欲研究,故未與該會續有接洽,然亦無反對之意見也。歐洲已往著名靈學家如胡穆 (M. Home)、 巴拉丁諾 (Eusapia Paladino) 等,其成績昭彰在人耳目,雖白朗寧氏 (Browning) 作有著名之詩 Mr. Sludge the Medium 以嘲之,然終未發覺其有任何詐偽之行為。去冬美國靈學家格蘭頓博士 (Dr. Grandon) 夫婦遊倫敦,頗引起社會注意,十二月六日巴黎之 Daily Mail 報曾著社論,要求格氏公開實驗,邀集科學及靈學兩界人士,為嚴密之接洽,俾明真相。謂此事與世界進化及人生觀,關係最重。

The spirit of any sentient being is undying; only the physical form changes. Thus the universe consists of two parts—one corporeal, the other spiritual. How unwise and risky then for us to struggle merely for outward possessions, without a thought of the conditions after death. Millions of persons die suddenly from accidents, heart failure, plague and other causes. Like all others, I, too, shall have, one day, to leave my physical body, WHEN, WHERE, HOW, I don’t know. Is it not worthwhile to give a thought to this weighty problem?22

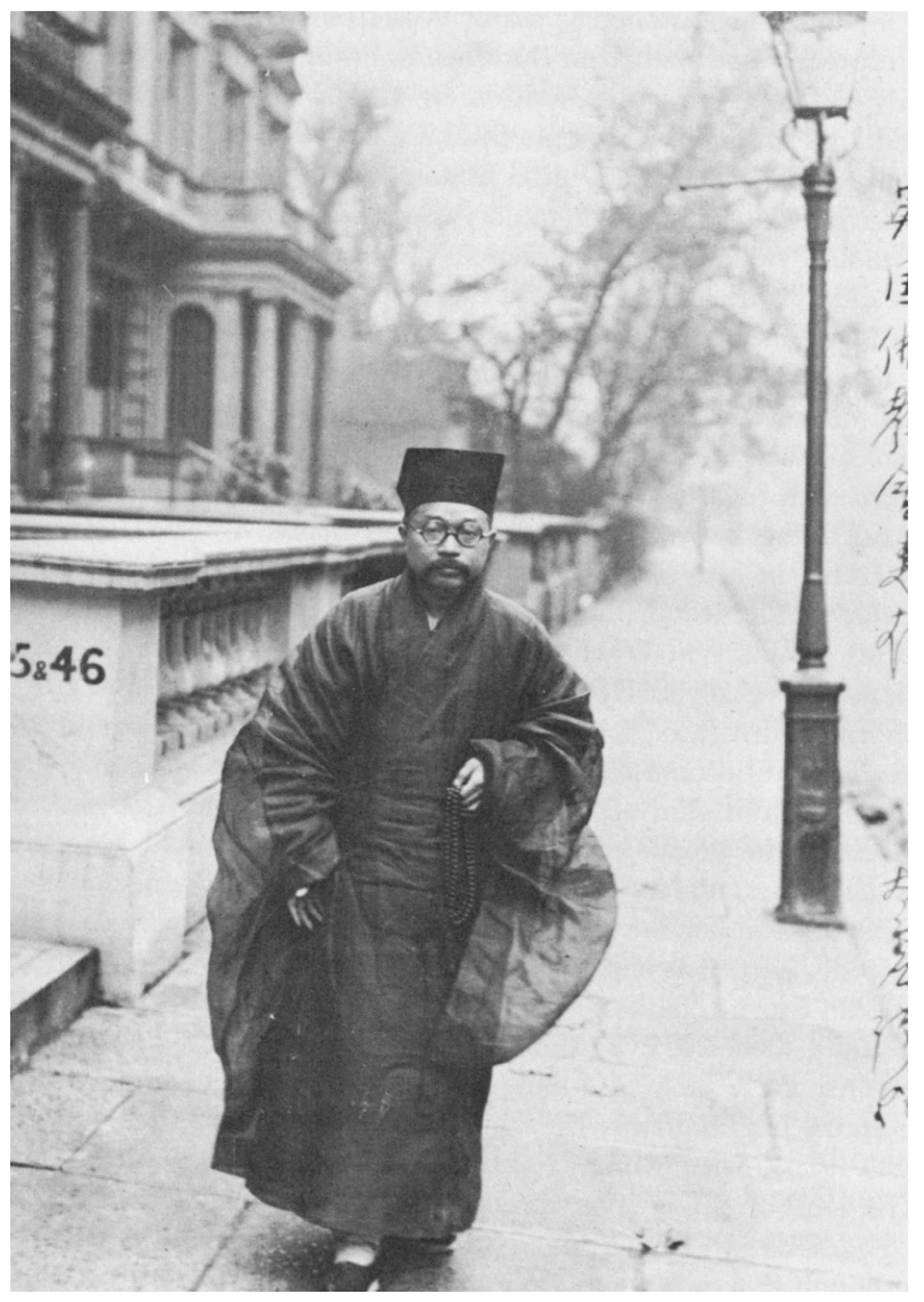

3. Lü Bicheng and the Buddhist Revival

1. From now on, the existing Buddhist associations in England and Ireland should contact and support each other.

英倫及愛爾蘭原有之各佛學會自此互相聯絡,公策進行。

2. A great Buddhist union should be established. Chinese, Japanese, and Thai Buddhist student associations should be affiliated with it.

組織佛教大聯合會,凡中國、日本、暹羅等國之學生佛教研究會皆屬之。

3. According to the lunar calendar, on the fifteenth day of the seventh month of each year, when the full moon appears, a Buddhist assembly should be held in London.

倫敦於每年華曆七月十五,月圓之時,開大會演講佛教。

4. Activities in London should be spread to the counties of England.29

由倫敦推及各行省。

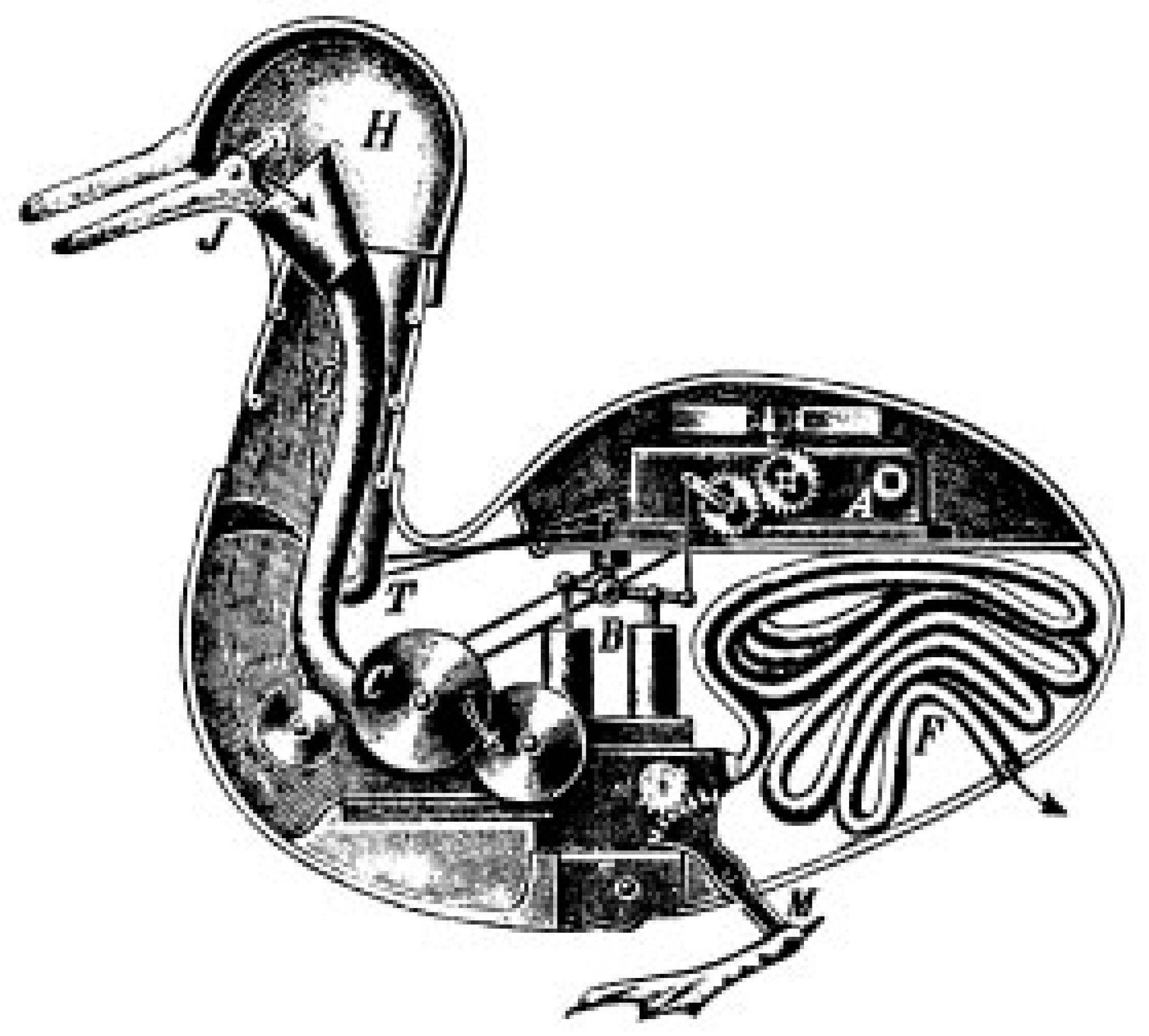

There are such terms as taxin tong 他心通 (telepathy) and tianyan tong 天眼通 (clairvoyance) in Buddhism, which British psychologist W. Medongall discusses in great detail in his book Body and Mind. The reporter [Lü Bicheng] has heard from Mr. Yan Jidao (the person who first translated Evolution and Ethics in our country) that in Britain, two students, A and B, stayed in two different dorms. Student A felt bored. He drew a duck and colored it in silver. He then laughed at it because it did not make any sense. When he entered student B’s room, [he saw] that student B had drawn a silver teapot with an oblate body and a long nozzle, which looked exactly like the duck that student A drew. In Europe, the most famous event was witnessed by a renowned figure. At a banquet, Swedenborg suddenly stood up with a cup in his hand. He looked into the distance and told people that some place six hundred miles away was on fire. Later, people made an inquiry. There was indeed a fire in that place when Swedenborg attended the banquet.33

佛家有他心通 (telepathy) 天眼通 (clairvoyance) 諸法,英國心理家麥當哥爾氏 (W. Medongall) 所著 Body and Mind 一書,亦詳言之。記者曩聞嚴幾道先生 (即吾國首譯天演論者) 言,英國某校甲乙兩生,各居寄宿舍,僅隔一壁。甲生無聊,隨意畫一鴨,而塗以銀色,自笑其無理由。及入乙生舍,則乙生方繪一銀茶壺,壺式扁而嘴長,形極如鴨,與甲生所繪吻合,亦此類也。在歐洲,最著之故事由名宿證得者,即瑞登保 (Swedenborg) 於眾客筵席間,忽停杯遠矚,謂六百里外,某地正肇焚如。後向該地調查,果曾失火,恰當瑞氏宴飲之時也。

It was in the year 1756, as Herr von Swedenborg, at the end of the month of September at four o’clock in the afternoon, returning from a journey to England, disembarked at Gothenburg. Mr. William Castel invited him over along with a company of fifteen persons. That evening around six o’clock Herr von Swedenborg left and then returned to the drawing room pale and agitated. He said that there was even now a dangerous conflagration in Stockholm in the Südermalm [southern suburb] (Gothenburg lies more than fifty miles from Stockholm), and the fire was rapidly spreading. He was restless and went out frequently. He said that the house of one of his friends, whom he named, already lay in ashes and his own house was in danger. At eight o’clock, after he had gone out again, he joyfully exclaimed: “Praise be to God, the conflagration has been extinguished, three doors from my own house!” This report caused a great stir in the whole city and especially in the gathering, and that same evening someone gave a report to the governor. On Sunday morning, Swedenborg was called to the governor. He asked him about the matter. Swedenborg described the conflagration exactly, how it started, how it had been extinguished and the time it lasted. That same day the report spread through the whole city, where it now caused an even greater stir because the governor had taken notice of it, for many were concerned for their friends or for their goods. On Monday evening, a mounted messenger, dispatched by the Stockholm Chamber of Commerce at the time of the fire, arrived in Gothenburg. In his letters, the conflagration was described in the exact manner as it had been related. On Tuesday morning, a royal courier arrived at the governor’s with news of the fire, the damage, its cause, and the houses that it affected; this report did not differ in the least from the one Swedenborg had given at the same time, for the conflagration had been extinguished at eight o’clock.35

In my opinion psychical research is highly relevant to philosophy for the following reasons. There are certain limiting principles which we unhesitatingly take for granted as the framework within which all our practical activities and our scientific theories are confined. Some of these seem to be self-evident. Others are so overwhelmingly supported by all the empirical facts which fall within the range of ordinary experience and the scientific elaborations of it (including under this heading orthodox psychology) that it hardly enters our heads to question them. Let us call these Basic Limiting Principles. Now psychical research is concerned with alleged events which seem prima facie to conflict with one or more of these principles. Let us call any event which seems prima facie to do this an Ostensibly Paranormal Event.37

After the European War, the claim that science is almighty was not as strong as before. Many intellectuals began paying attention to the East and Eastern cultures, which is good news for the future of humans. Everyone should know that European theories may benefit human beings’ material life; however, with regard to the spiritual side, most of the European theories teach people how to behave like animals.40

自歐戰告終,全世界於科學萬能之呼聲,不及曩昔之銳利。許多哲士漸漸注意到東方及東方的文化。這是人類未來的福音。各位要知道,歐洲諸學說其關於物質方面,雖亦有許多裨益於人羣,但於精神方面,則大部分是教人習禽獸。

Nowadays, the Europeans are dissatisfied with the transient nature of life. They want to know where the soul will go after death. This can be seen as an insight into life. Among all the answers to this question, the Buddhist explanation is the most satisfactory and accurate.41

今歐人不滿意於肉體生命之短促,而欲知靈魂之究竟何往,可謂人生觀之一種覺悟,然欲解決此問題,則以佛說最為圓滿精密。

- The visual consciousness (yan shi 眼識)

- The auditory consciousness (er shi 耳識)

- The olfactory consciousness (bi shi 鼻識)

- The gustatory consciousness (she shi 舌識)

- The tactile consciousness (shen shi 身識)

- The mano consciousness (yi shi 意識)

- The manas consciousness (mona shi 末那識)

- The ālayavijñāna consciousness (alaiye shi 阿賴耶識)

4. Lü Bicheng and the Movement for Animal Protection

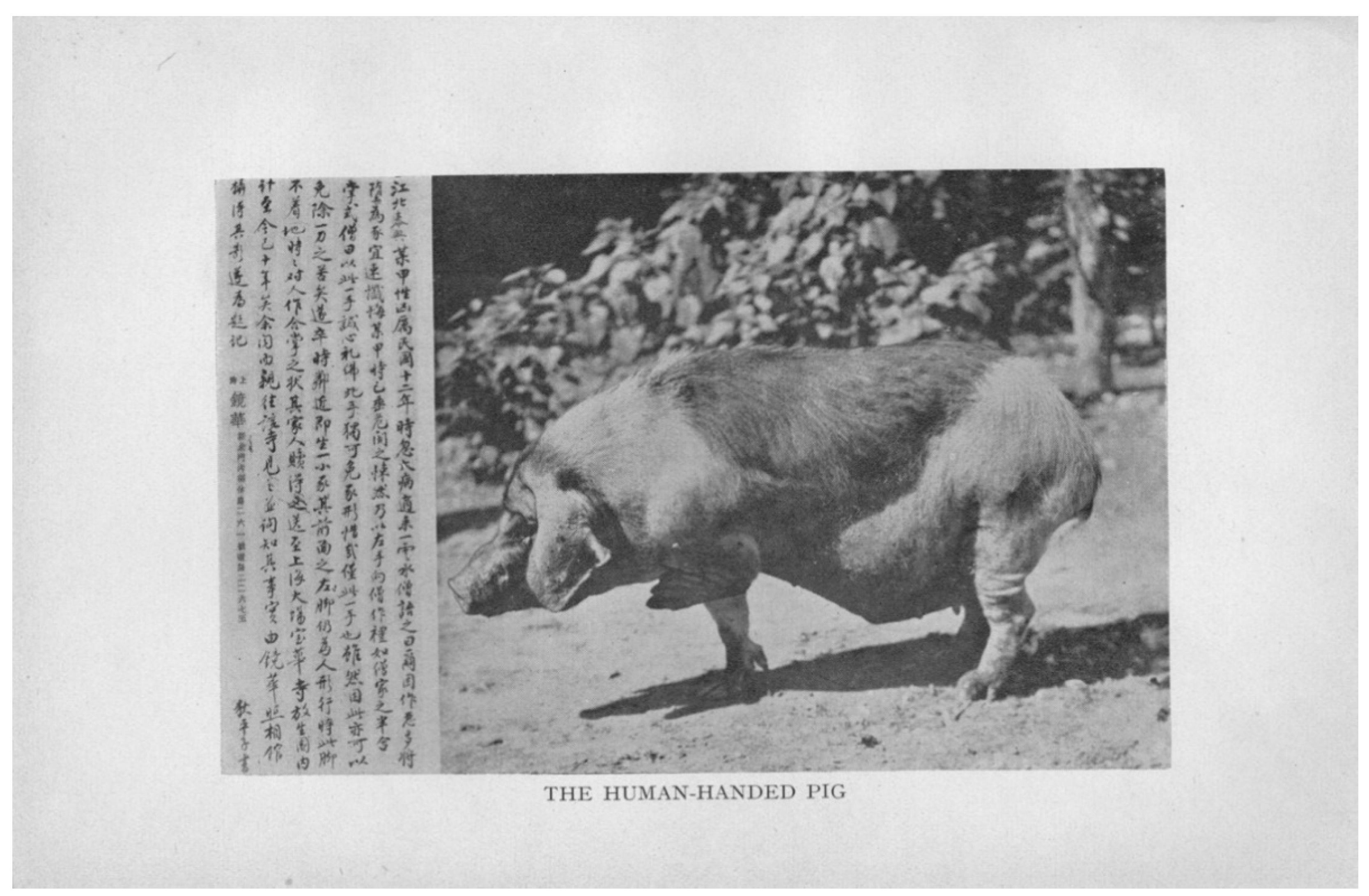

This and the following two kinds of realms i.e. ghost and hell are called “The Three Bad Realms of Existence.” The highest kind of animals are those such as the Garudas (the celestial golden wind birds), royal dragons etc. The common animals but of good nature such as horses, cows, birds etc. The animals of lowest form and of evil nature such as snakes, scorpions, and those which live in darkness or in damp places such as the rats, bugs etc. These unfortunate beings are reincarnated from guilty people according to the nature of their sins who have fallen into various forms of animals under the karmic law. And partly due to Vidjnana the strong mentality especially when one is approaching death, Vidjnana led them temporarily to be involved into the wrong forms of life, such as the case of the Empress of Liong Dynasty. A snake has two small sacs jointed on each of its jaws, in the sacs the poisonous fluids are contained, so it would be fatal when it bites any one. (This proves the falsehood of the theory of Creation, if a Creator is of good nature himself, he would not create such a thing of ill-will.) Those who have a malicious nature and act with the intention of injuring others will be reborn as such harmful animals. All kinds of animals some haired, some feathered, others scaly or reptiled, have latently inhered the Buddha-nature in them. Hence all of them deserve consideration and respect. This is the doctrine of Equality peculiar to Buddhism. No matter if they were reincarnated from guilty ones, millions upon millions of years may pass, but ultimately they will be delivered.48

At that time, the assembled multitude all saw the dragon girl in the space of an instant turn into a man, perfect bodhisattva conduct, straightway go southward to the world sphere Spotless, sit on a jeweled lotus blossom, and achieve undifferentiating, right, enlightened intuition, with thirty-two marks and eighty beautiful features setting forth the fine dharma for all living beings in all ten directions. At that time, in the Saha world sphere bodhisattvas, voice hearers, gods, dragons, the eightfold assembly, humans, and nonhumans, all from a distance seeing that dragon girl achieve Buddhahood and universally preach dharma to the men and gods of the assembly of that time, were overjoyed at heart and all did obeisance from afar. Incalculable living beings, hearing the dharma and understanding it, attained to nonbacksliding.50

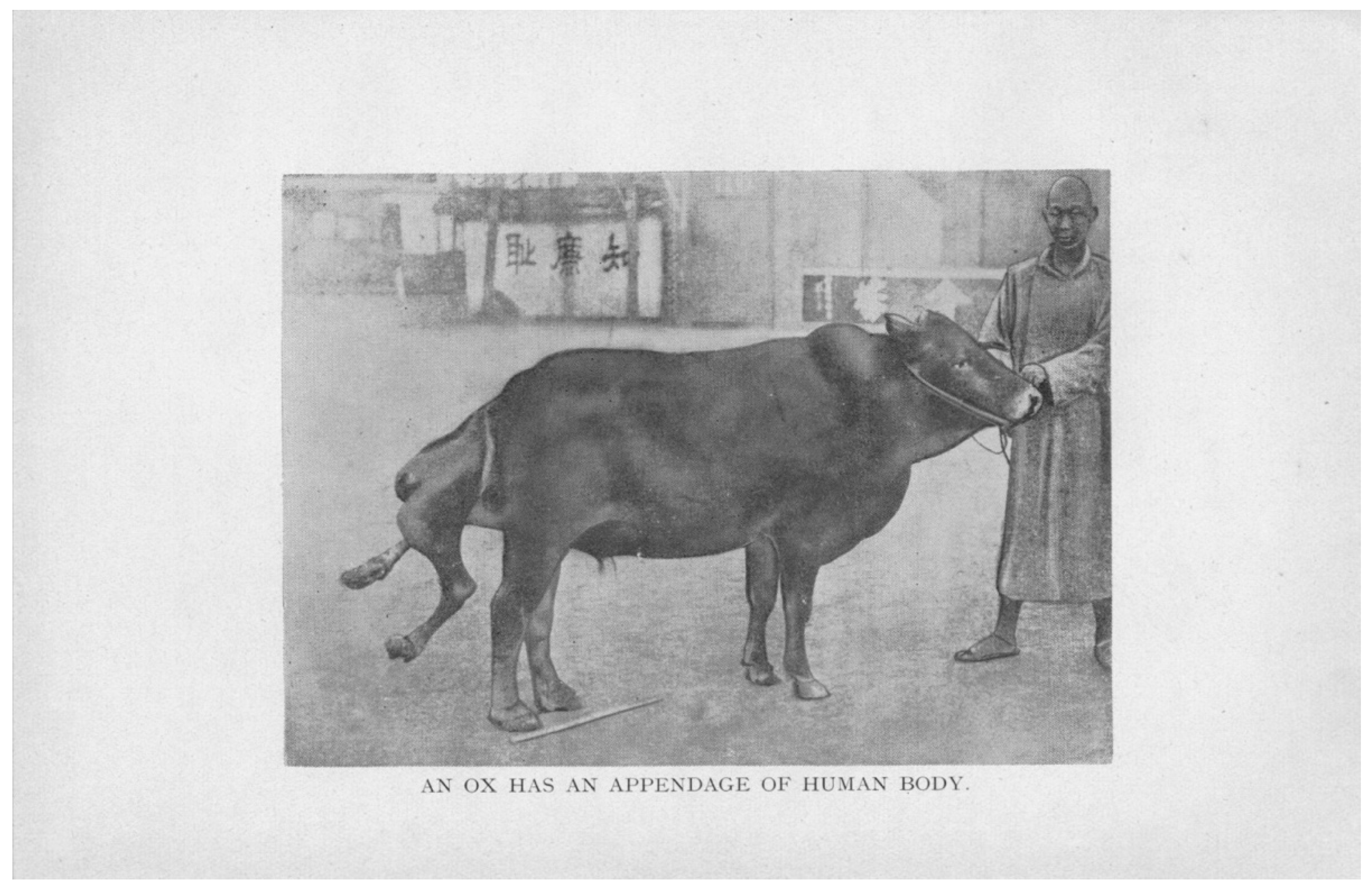

It was born in Tung-Jen city of Sze-Chuan province, China. It is said, there was a man who had committed adultery and murder. When he was approaching death, he confessed what he had done, and stated where he would be born as an ox. According to the address, his family found the newly born ox, two bodies joined together, one part animal and the other human. The fact was thus broadcast. This ox was led to the court, and a photo of it taken by the magistrate’s order.56

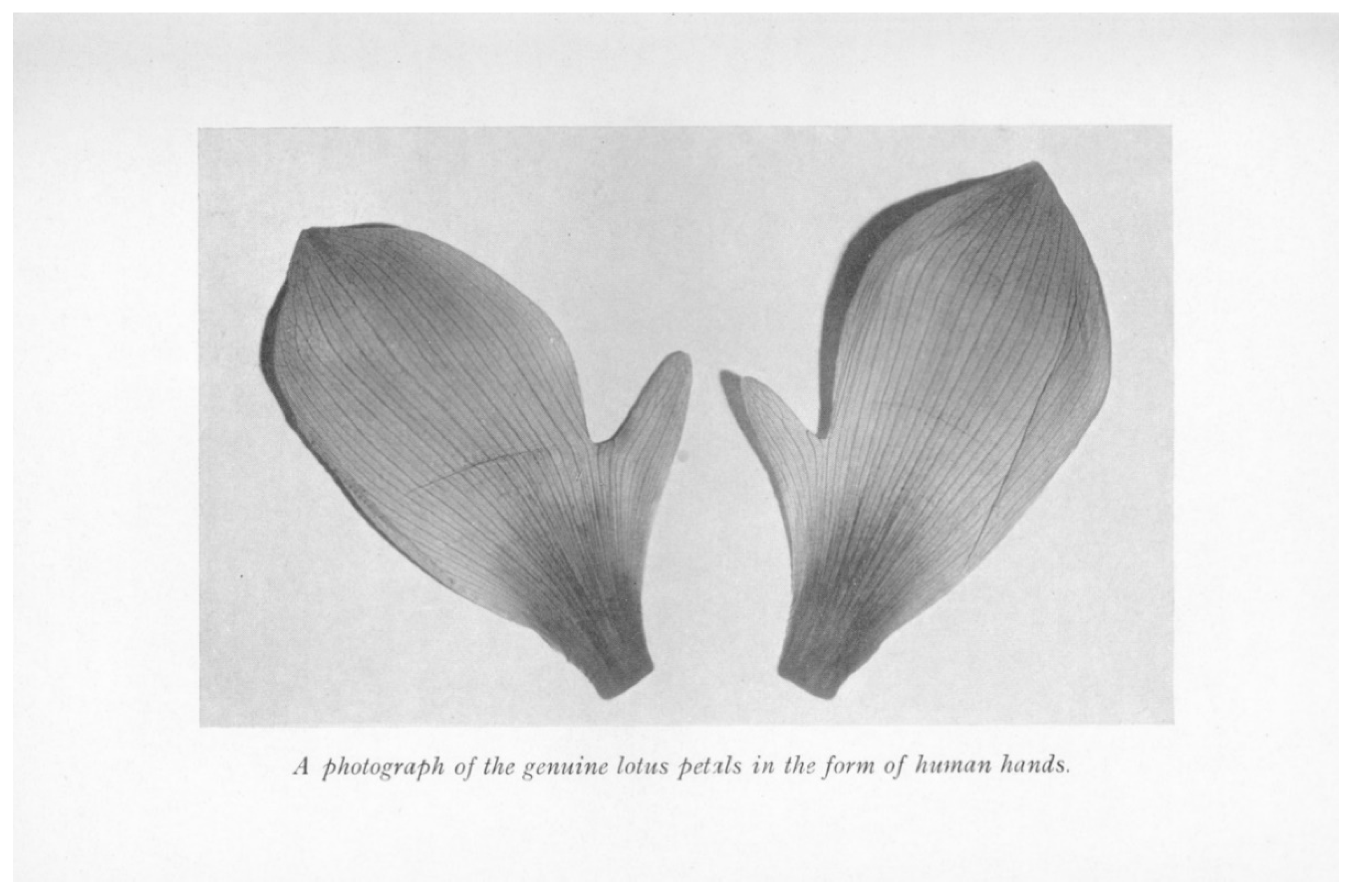

Six months after the discovery of the “Lotus hands” as described in Appendix (I), a further unusual manifestation revealed to me upon my drawing of a portrait representing the King of the Tenfold Vow, namely the Bodhisattva Samantabhadra. The work occupied seven days. On the morning of the last day, after the completion of the drawing, it was the 18th of February 1935 C.E. when I arose from bed, I was surprised to see that the water in the washbasin of my chamber, which I had used to wash my hands on the previous evening, contained much earthy matter, which had sunk to bottom of the basin and formed a picture with a resemblance to a lotus flower. The figure was about seven inches in diameter, and round in shape, fully covered the round bottom of the basin. I counted its petals, which were exactly ten, corresponding to the number of the Ten Vows. I poured the water before I used the basin again. It is a pity that I had not a camera at hand, otherwise a photograph of it could have been taken.58

5. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Broad, Charlie Dunbar. 1953. Religion, Philosophy and Psychical Research. New York: Harcourt, Brace & Company, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Campany, Robert Ford. 2012. Signs from the Unseen Realm: Buddhist Miracle Tales from Early Medieval China. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Hsi-yüan. 2002. “Zongjiao”—Yige Zhongguo jindai wenhuashi shang de guanjian ci 「宗教」—一個中國近代文化史上的關鍵詞 [“Religion”: A keyword in the cultural history of modern China]. Xin shixue 新史學 [New History] 13: 37–66. [Google Scholar]

- Duara, Prasenjit. 1991. Knowledge and Power in the Discourse of Modernity: The Campaigns against Popular Religion in Early Twentieth-Century China. The Journal of Asian Studies 50: 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Chunwu. 2010. Qingmo minchu nü ciren Lü Bicheng yu guoji shushi yundong 清末民初女詞人呂碧城與國際蔬食運動 [Lü Bicheng and the worldwide vegetarian movement in the early twentieth century]. Qingshi yanjiu 清史研究 [The Qing History Journal] 2: 105–13. [Google Scholar]

- Faure, Bernard. 2003. The Power of Denial: Buddhism, Purity, and Gender. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fong, Grace S. 2004. Alternative Modernities, or a Classical Woman of Modern China: The Challenging Trajectory of Lü Bicheng’s (1883–1943) Life and Song Lyrics. Nan Nü: Men, Women & Gender in Early & Imperial China 6: 12–59. [Google Scholar]

- Fong, Grace S. 2008. Reconfiguring Time, Space, and Subjectivity: Lü Bicheng’s Travel Writings on Mount Lu. In Different Worlds of Discourses: Transformations of Gender and Genre in Late Qing and Early Republican China. Edited by Nanxiu Qian, Grace S. Fong and Richard J. Smith. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 87–114. [Google Scholar]

- Fong, Grace S. 2015. Between the Literata and the New Woman: Lü Bicheng as Cultural Entrepreneur. In The Business of Culture: Cultural Entrepreneurs in China and Southeast Asia, 1900–1965. Edited by Christopher Rea and Nicolai Volland. Vancouver: UBC Press, pp. 35–61. [Google Scholar]

- Friess, Horace L. 1957. The Department of Religion. In A History of the Faculty of Philosophy, Columbia University. New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 146–67. [Google Scholar]

- Goossaert, Vincent, and David A. Palmer. 2011. The Religious Question in Modern China. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, Beata. 2003. Daughters of Emptiness: Poems of Chinese Buddhist Nuns. Somerville: Wisdom Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, Beata. 2008a. Da Zhangfu: The Gendered Rhetoric of Heroism and Equality in Seventeenth-Century Chan Buddhist Discourse Records. Nan Nü: Men, Women and Gender in China 10: 177–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, Beata. 2008b. Eminent Nuns: Women Chan Masters of Seventeenth-Century China. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, Beata. 2014. Writing Oneself into the Tradition: Spiritual Autobiographies by Female Chan Buddhist Masters. In Gendering Chinese Religion: Subject, Identity, and Body. Edited by Jinhua Jia, Xiaofei Kang and Ping Yao. Albany: SUNY Press, pp. 47–70. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, Beata. 2015. Women and Gender in the Discourse Records of Seventeenth-Century Sichuanese Chan Masters Poshan Haiming and Tiebi Huiji. The Chinese Historical Review 22: 52–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haichao yin. 2003a. Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe, vol. 1.

- Haichao yin. 2003b. Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe, vol. 19.

- Hammerstrom, Erik J. 2015. The Science of Chinese Buddhism: Early Twentieth-Century Engagements. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Haynes, Renée. 1982. The Society for Psychical Research 1882–1982: A History. London: Macdonald & Co., Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Kewu. 2007. Minguo chunian Shanghai de lingxue yanjiu: Yi “Shanghai lingxue hui” wei li 民國初年上海的靈學研究:以“上海靈學會”為例 [Psychical research in early republican Shanghai: Taking the Society for Psychical Research in Shanghai as an example]. Zhongyang yanjiuyuan jindaishi yanjiusuo jikan 中央研究院近代史研究所集刊 [Academia Sinica Modern History Institute Bulletin] 55: 99–136. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Kewu. 2013. Zhongguo jindai sixiang zhong de “mixin” 中國近代思想中的「迷信」 [“Superstition” in modern Chinese thought]. In Higashi Ajia ni okeru chiteki kōryū: kii konseputo no saikentō 東アジアにおける知的交流:キイコンセプトの再検討 [Intellectual exchange in modern East Asia: Rethinking key concepts]. Edited by Suzuki Sadami and Ryū Kenki. Kyoto: Kokusai Nihon Bunka Kenkyū Sentā. [Google Scholar]

- Hurvitz, Leon. 2009. Scripture of the Lotus Blossom of the Fine Dharma. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, Zhe. 2008. Secularization as Religious Restructuring: Statist Institutionalization of Chinese Buddhism and Its Paradoxes. In Chinese Religiosities: Afflictions of Modernity and State Formation. Edited by Mayfair Mei-hui Yang. Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 233–60. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, Zhe. 2015. Buddhist Institutional Innovations. In Modern Chinese Religion II: 1850–2015. Edited by Vincent Goossaert, Jan Kiely and John Lagerwey. Leiden and Boston: Brill, vol. 2, pp. 731–66. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, Le 康樂. 2005. Sushi yu Zhongguo fojiao 素食與中國佛教 [Vegetarianism and Chinese Buddhism]. In Lisu yu zongjiao 禮俗與宗教 [Custom and religion]. Edited by Lin Fushi. Beijing: Zhongguo da baike quanshu chubanshe, pp. 128–72. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, Xiaofei. 2015. Women and the Religious Question in Modern China. In Modern Chinese Religion II: 1850–2015. Edited by Vincent Goossaert, Jan Kiely and John Lagerwey. Leiden & Boston: Brill, vol. 1, pp. 491–559. [Google Scholar]

- Kant, Immanuel. 2002. Kant on Swedenborg: Dreams of a Spirit-Seer and Other Writings. Translated by Gregory R. Johnson, and Glenn Alexander Magee. Edited by Gregory R. Johnson. West Chester: Swedenborg Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Lydia H., Rebecca E. Karl, and Dorothy Ko, eds. 2013. Birth of Chinese Feminism: Essential Texts in Transnational Theory. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Xun. 2009. Daoist Modern: Innovation, Lay Practice, and the Community of Inner Alchemy in Republican Shanghai. Cambridge: Harvard University Asia Center. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez, Donald S., Jr. 2008. Buddhism and Science: A Guide for the Perplexed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lü, Bicheng. 1929. Lü Bicheng ji 呂碧城集 [The works of Lü Bicheng]. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju. [Google Scholar]

- Lü, Bicheng. 1932. Oumei zhiguang 歐美之光 [The light from Europe and the United States]. Shanghai: Foxue shuju. [Google Scholar]

- Lü, Bicheng. 1939. The Two Buddhist Books in Mahayana. Oxford: Kemp Hall Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lü, Bicheng. 1940. An Outline of Karma, (pamphlet).

- Lü, Bicheng. 2007. Lü Bicheng shiwen jianzhu 呂碧城詩文箋注 [Collated and annotated collection of Lü Bicheng’s poetry and prose]. Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- McGarry, Molly. 2008. Ghosts of Futures Past: Spiritualism and the Cultural Politics of Nineteenth-Century America. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- McMahan, David L. 2008. The Making of Buddhist Modernism. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Monroe, John Warne. 2008. Laboratories of Faith: Mesmerism, Spiritism, and Occultism in Modern France. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Owen, Alex. 1990. The Darkened Room: Women, Power and Spiritualism in Late Victorian England. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Owen, Alex. 2004. The Place of Enchantment: British Occultism and the Culture of the Modern. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pittman, Don Alvin. 2001. Toward a Modern Chinese Buddhism: Taixu’s Reforms. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press. [Google Scholar]

- Poon, Shuk-wah. 2015. Husheng yu tusha: 1930 niandai Shanghai de dongwu baohu yu fojiao yundong 護生與屠殺:1930年代上海的動物保護與佛教運動 [Protecting and slaughtering animals: Animal protection and Buddhist movements in Shanghai in the 1930s]. In Gaibian Zhongguo zongjiao de wushinian: 1898–1948 改變中國宗教的五十年: 1898–1948 [Fifty years that changed Chinese religions: 1898—1948]. Edited by Paul Katz and Vincent Goossaert. Taipei: Institute of Modern History, Academia Sinica, pp. 399–426. [Google Scholar]

- Rowlands, Mark. 2002. Animals Like Us. London and New York: Verso. [Google Scholar]

- Sharp, Lynn L. 2006. Secular Spirituality: Reincarnation and Spiritism in Nineteenth-Century France. Lanham: Lexington Books. [Google Scholar]

- Singer, Peter. 1983. Animal Liberation: Towards an End to Man’s Inhumanity to Animals. Wellingborough and Northamptonshire: Thorsons Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Tarocco, Francesca. 2007. The Cultural Practices of Modern Chinese Buddhism: Attuning the Dharma. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Welch, Holmes. 1968. The Buddhist Revival in China. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Shengqing. 2004. “Old Learning” and the Refeminization of Modern Space in the Lyric Poetry of Lü Bicheng. Modern Chinese Literature and Culture 16: 1–75. [Google Scholar]

- Xueyu. 2015. Buddhism and the State in Modern and Contemporary China. In Modern Chinese Religion II: 1850–2015. Edited by Vincent Goossaert, Jan Kiely and John Lagerwey. Leiden and Boston: Brill, vol. 1, pp. 261–301. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Jinyu. 2013. Lü Bicheng wenxue yu sixiang 呂碧城文學與思想 [The literary works and thoughts of Lü Bicheng]. Gaoxiong: Foguang wenhua shiye youxian gongsi. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Chun-fang. 1981. The Renewal of Buddhism in China: Chu-hung and the Late Ming Synthesis. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Chun-fang. 2013. Passing the Light: The Incense Light Community and Buddhist Nuns in Contemporary Taiwan. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | See (Liu 2009, pp. 59–67). |

| 2 | See (Tarocco 2007, pp. 63–66). |

| 3 | |

| 4 | |

| 5 | |

| 6 | During the same period, Lü’s literary talent also appealed to politicians such as Yuan Shikai 袁世凱 (1859–1916) and Fan Zengxiang 樊增祥 (1846–1931) who hired her as a secretary and supported her activities in the movement for women’s liberation. |

| 7 | These articles were all published in 1904. |

| 8 | This school later became Beiyang Women’s Normal School (Beiyang nüshifan xuetang 北洋女師範學堂). |

| 9 | Liang Qichao, “Lun nüxue,” in (Liu et al. 2013, pp. 189–203). |

| 10 | See (Kang 2015, p. 503). In China, the question of women’s religiosity was subject to male constructions. See (Grant 2008a). |

| 11 | (Duara 1991, p. 76). On the formation and evolution of the notion of “mixin” in the modern period, see (Huang 2013, pp. 185–200). On how “zongjiao” 宗教 was accepted as a modern concept corresponding to the Western term “religion” in the same period, see (Chen 2002). |

| 12 | Chen taught Lü methods specifically designed for women practitioners to improve their health. Nevertheless, Lü soon lost her interest in Daoism probably because female alchemy was not intellectually stimulating to her. |

| 13 | Lü Bicheng, “Yu zhi zongjiao guan” 予之宗教觀 (My Views on Religion), in (Lü 2007, pp. 478–82). |

| 14 | See (Fong 2004, p. 32). |

| 15 | See (Friess 1957, p. 151). |

| 16 | Lü’s travel experiences were recorded in Oumei manyou lu 歐美漫遊錄 (Travel Notes in Europe and the United States), see (Lü 1929). |

| 17 | (Lü 2007, pp. 294–95). This article was published in the Shanghai shibao 上海時報 (Shanghai Times) in December 1930. I translated this paragraph from Chinese into English. |

| 18 | When she was young, Lü exhibited her interest in Buddhism and incorporated Buddhist ideas into poetic writing. Later, her exposure to psychical research strengthened her Buddhist beliefs. |

| 19 | See (Haynes 1982, p. xiii.) |

| 20 | Lü Bicheng, “Gui da dianhua,” (Lü 2007, p. 444). |

| 21 | Lü Bicheng, “Yinguo,” (Lü 2007, pp. 444–45). |

| 22 | Lü Bicheng, “What Becomes of Man after Death,” (Lü 1940, p. 57). An Outline of Karma was written in English and was published by Lü herself. |

| 23 | On spiritualism in Europe and America, see (Owen 1990, 2004; Monroe 2008; Sharp 2006; McGarry 2008). |

| 24 | |

| 25 | On the tension between Buddhism and the state in the modern period, see (Ji 2008; Xueyu 2015). On reforms in the Buddhist community, see (Ji 2015). |

| 26 | See (Hammerstrom 2015, pp. 1–17). |

| 27 | |

| 28 | |

| 29 | Lü Bicheng, “Fojiao zai ouzhou zhi fazhan” 佛教在歐洲之發展 (The Development of Buddhism in Europe), (Lü 2007, pp. 246–50). I translated these four agreements from Chinese into English. |

| 30 | In her later years, Lü published two books in English. One book, The Two Buddhist Books in Mahayana, contains her translations of Buddhist texts from the Huayan and Pure Land traditions. The other book, An Outline of Karma, focuses on the notion of karmic retribution. |

| 31 | |

| 32 | See (Lü 2007, pp. 268–88). |

| 33 | (Lü 2007, p. 298). I translated this part from Chinese into English. |

| 34 | For more about the Society for Psychical Research in Shanghai and Yan Fu’s involvement in it, see (Huang 2007). |

| 35 | “Letter to Charlotte von Knobloch” was written on 10 August 1763. In the letter, the name of Herr von Swedenborg refers to Emanuel Swedenborg. (Kant 2002, pp. 70–71). |

| 36 | On Immanuel Kant’s interest in psychical research, see (Broad 1953, pp. 116–55). |

| 37 | |

| 38 | See (Broad 1953, pp. 27–67). |

| 39 | |

| 40 | Tang Dayuan, “Fojia de xinli jianshe” 佛家的心理建設 (Psychological Development in Buddhism), in (Haichao yin 2003b, pp. 43–45). I translated this paragraph from Chinese into English. |

| 41 | (Lü 2007, p. 299). I translated this part. |

| 42 | Liang mentioned that even though Westerners philosophers such as Henri Bergson (1859–1941) and Rudolf Euken (1846–1926) showed interest in spiritual studies, they were not familiar with the Buddhist Consciousness-Only School and Chan Buddhism. See Liang Qichao, “Kexue wanneng zhi meng” 科學萬能之夢 (Dream of the Omnipotence of Science), in (Haichao yin 2003a, pp. 433–35). |

| 43 | |

| 44 | Lü’s ideas of animal protection and non-killing (Jiesha fangsheng 戒殺放生) were inspired by the Pure Land doctrine. See (Lü 1939, pp. 85–149). For more about Lü’s contribution to the movement for animal protection, see (Fan 2010; Fong 2015; Poon 2015). |

| 45 | Lü Bicheng, “Zhi Lundun jinzhi nuedai shengchu hui han” 致倫敦禁止虐待牲畜會函 (A Letter to the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals in London), (Lü 2007, pp. 242–43). |

| 46 | |

| 47 | |

| 48 | Lü Bicheng, “The Ten Dharma-dhatus,” (Lü 1940, pp. 49–50). The original text was written in English. |

| 49 | These six realms refer to the realms of hell, hungry ghost, animal, asura, human, and god. |

| 50 | |

| 51 | On various interpretations of the story of the dragon girl, see (Faure 2003, pp. 94–95). It is unclear how Lü understood the dragon girl’s gender transformation. |

| 52 | Lü Bicheng, “Mouchuang Zhongguo baohu dongwu hui zhi yuanqi” 謀創中國保護動物會之緣起 (Reasons to Create the Society for the Protection of Animals in China), (Lü 2007, pp. 237–41). |

| 53 | This book was printed by the Buddhist Book Store (Foxue shuju 佛學書局) and was circulated as a morality book (cishan shuji 慈善書籍, or simply, shanshu 善書). |

| 54 | “Shi renzhong ehua zhi kexue” 使人種惡化之科學 (Science That Debauches the Human Species), (Lü 1932, pp. 78–79). |

| 55 | |

| 56 | |

| 57 | On Buddhist miracle tales in medieval China, see (Campany 2012). On advocacy of vegetarianism in pre-modern China, see (Kang 2005; Yu 1981, pp. 76–90). |

| 58 | (Lü 1939, p. 50). The original text was written in English. |

| 59 | Beata Grant’s and Chun-fang Yu’s pioneering studies on women and religion in pre-modern China and present-day Taiwan have set great examples for scholars who study gender in Chinese religions. Following their works, scholars have begun to focus on women and religion in modern China. See (Grant 2003, 2008a, 2008b, 2014, 2015; Yu 2013). |

| 60 |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, P. Seeking the Dharma on the World Stage: Lü Bicheng and the Revival of Buddhism in the Early Twentieth Century. Religions 2019, 10, 558. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10100558

Liu P. Seeking the Dharma on the World Stage: Lü Bicheng and the Revival of Buddhism in the Early Twentieth Century. Religions. 2019; 10(10):558. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10100558

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Peng. 2019. "Seeking the Dharma on the World Stage: Lü Bicheng and the Revival of Buddhism in the Early Twentieth Century" Religions 10, no. 10: 558. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10100558

APA StyleLiu, P. (2019). Seeking the Dharma on the World Stage: Lü Bicheng and the Revival of Buddhism in the Early Twentieth Century. Religions, 10(10), 558. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10100558