1. Introduction

In the prevailing competitive and challenging international economic situation, a viable and dynamic small and medium enterprises (SMEs) sector is essential to the economic progress of the respective country [

1]. Similarly, small and medium firms are considered as the engine of growth and play a significant part in creating economic development [

2]. In an earlier study, Hashim et al. described that mostly countries reply on the performance of small and medium-sized firms for the growth and uplift of the economy [

3]. However, business firms face uncertainty and challenges in the competitive business environment, and unfavorable circumstances in recent years have raised the challenges to improve the performance of small firms and SMEs [

4]. Small firms and SMEs emphasize the main objective to secure the competitive advantages by attaining sustainable business growth [

5]. Unfortunately, small businesses face a high rate of failure worldwide. Previous literature indicated that almost 40% of firms face failure during the first two years of their business startups in various countries worldwide [

3]. In the same manner, researchers have strongly argued that small firms’ failure rate is also higher in developing countries than in the first world nations [

6]. The environment of doing business in the ecosystem industry of Pakistan is challenging and competitive, and the business environment is neither ideal nor favorable for small firms, and other SMEs [

7]. Small firms and SMEs have to adopt the best utilization strategy of their available resources to ensure firms sustainable growth in challenging and competitive business environment as they face challenging and competitive business environment and uncertainty in the business industry in Pakistan [

8]. These unfavorable circumstances encourage the small and medium-sized firms to overcome the unhealthy business environment in achieving their sustainable business growth [

9].

The entrepreneurial business network is a multifaceted business network of business firms, working together to achieve firm business objectives [

10,

11]. These objectives typically are operational and strategic, and business networks adopt it based on their role in the competitive environment in the market [

12]. There are two central categories of entrepreneurial business networks namely business associations and business firm aggregations, which help small and medium-sized enterprises to become more dynamic, innovative and competitive [

13]. An entrepreneurial business network is the socioeconomic business activity and a platform by which business executives and entrepreneurs meet with each other to discuss available business network opportunities. The entrepreneurial business network (EBN) also provides a platform to build relationships, identify, develop or act upon opportunities of business, share information and seek potential business partners for ventures [

14]. The entrepreneurial business network is a business social networking, which helps business people to connect and communicate with other entrepreneurs and managers to expand business interests by forming mutually beneficial business relationships [

15]. An entrepreneurial business network is a way of leveraging your business network and personal networks and relations to help bring you a regular supply of new business opportunities [

16]. The leading firms are nowadays gaining competitive business advantages through networked business models and tapping into talent from external sources to increase their growth [

17]. Rather than implementing rigid “built-to-last” processes, business firms are now constructing additional fluid “built-to-adapt” business networks in which each member firm focuses on its differentiation, relies and trusts increasingly on its business partners, suppliers, retailers and consumers to provide the rest [

18]. The entrepreneurial business network is one of the strategically essential resources, which permits small firms to grow in a dynamic and competitive business environment. Entrepreneurial business networks are contacts of small business owners and SMEs with other individuals or firms to obtain and share information and resources [

19].

Small and medium-sized business firms set up the long-term entrepreneurial business network to strengthen and enhance their dynamic capabilities in a competitive business environment [

16,

20]. The survival of small firms and small and medium enterprises SMEs depend on their business performance, which is associated with its economic growth and vice versa [

21]. The growth and sustainable performance of the small firms and SMEs do not rely on the outcome of a particular factor; however, it relies on the available resources and the combination of its dynamic capabilities, which fit all these factors together [

22]. Minai, Ibrahim and Law [

23] also stated that entrepreneurial networks are an intangible resource, which increases the efficiency of the small firm and SMEs. Scholars believed that entrepreneurial-network (EBN) is helpful to the entrepreneurs and small and medium-sized firms and enterprises might receive potential business benefits from business networking, such as an exchange of relationships, the latest information and the value-added credibility [

24]. However, it is a significant point to note that business networks are not static; instead, they are dynamic. The business network power determines the success of a small firm and its survival as a new venture or current business operation. Entrepreneurial networking contributes and leads to business growth [

25]. Thus, to encounter a fiercer business competition, it is critical for small firms to manage business networks for their growth and profitability [

26]. Therefore, it is one of the motives of this study to discover the impact, which might have on entrepreneurial networks and it could influence the sustainable performance of the small firms’ [

27]. Thus, small and medium-sized firms prefer to act as competitive by strengthening the entrepreneurial business network for their survival and growth in a specific era of an uncertain business environment [

28]. However, the existing body of literature support and evidence based on the resource-based view, small and medium enterprises achieve growth and sustainable performance through their resources and dynamic capabilities [

29].

Typically, small and medium-sized enterprises face a challenging and competitive business environment to maintain sustainable performance to pursue sustainable growth by utilizing their entrepreneurial business networks [

30]. Generally, small and medium-sized firms practice resources-based view guidelines for establishing and managing their dynamic capabilities to achieve sustainable performance [

31]. Small firms and enterprises dynamic capabilities are the higher order capabilities that reconfigure, integrate and coordinate the specific resources to face the turbulent, challenging and competitive business environment [

32]. Thus, dynamic capabilities play a central role to combat the rapidly changing and competitive environment, which influences SMEs and small firms’ sustainable performance [

33]. However, previous studies just focused on the acquisition of network resources, business networks density and its size [

34,

35]. The existing body of scientific literature lacks the studies examining the relationship between entrepreneurial business networks (EBN) and sustainable performance of small firms with the mediating role of dynamic capabilities.

This proposed study aims to address the gap of earlier studies by considering the dimensions of entrepreneurial business networks (entrepreneurial supplier interactions, entrepreneurial customer connections and entrepreneurial competitors’ interactions). This study offered the persistent effort to address the gaps and limitations identified from the previous studies in a connection of entrepreneurial business network, sustainable performance of small firms through dynamic capabilities of the firms. Furthermore, Pavlou and EI Sawy, established the model of dynamic capabilities with four dimensions sensing/identifying, integrating, learning and coordinating [

36]. However, Singh and Rao identified the dimensions of dynamic capabilities including combining capability, learning capacity, reconfiguration capability and alliance management capability [

37], and expanded the model of the dynamic capabilities of Pavlou and EI Sawy [

36]. Two dimensions are not available in each model, and that is the reason for combining both models to fill the likely knowledge gap in the existing body of literature. Therefore, this study hypothesizes the logical reasoning on the relationship between entrepreneurial business networks and small firms’ sustainable performance. The model of this study theorizes that entrepreneurial business network (EBN) enhances the sustainable performance of small firms and its dynamic capabilities mediate the relationship between EBN and small firms’ sustainable performance. However, an in-depth review indicated that the existing body of literature lacks this gap and there are some prominent limitations. Past literature evidenced that most of the studies central emphasis was on a large sample size.

5. Discussion

This study planned a purposeful effort to examine the relationship between the entrepreneurial business network and small firms’ sustainable performance with the mediating role of dynamic capabilities [

1,

4,

9,

10,

15,

24]. There is an absolute requirement of future studies to investigate the social dimensions of entrepreneurship primarily highlighting the findings of entrepreneurial activities in response to social interaction and communication within small firms’ mechanisms [

38]. The background information has provided a platform to small firms and small and medium enterprises (SMEs) for conducting a study to examine how dynamic capabilities mediate the relationship between the entrepreneurial business network and small firms. This study bridges it to a better level of information development. We have designed this proposed study addressing and bridging the literature gap based on an intensive literature review. This study examined how a small firm’s dynamic capabilities mediated the relationship between a small firm’s business performance and entrepreneurial business network. The findings contributed to the existing scientific knowledge by viewing the link of entrepreneurial business network and dynamic capabilities with a small firm’s performance. The results are beneficial for the owners and managers to address the problems and enhance firms’ competitiveness for business growth [

102]. The existing body of literature lacks the proper examination in the context of Pakistan, and the main reason was the unavailability of exact information on small firms [

103]. Ul Haq et al. explained that limited research existed on small firms and they recommended further work on entrepreneurial research and small firms sustainable performance [

104]. McDonald, Gan, Fraser, Oke and Anderson [

105] reviewed the entrepreneurship research methods and they identified that there were fewer designs at the micro-level and this research aimed to explore the relationship between entrepreneurial business network (EBN) firms sustainable performance; however, it was surprisingly limited [

106].

In the existing body of literature, dynamic capabilities is an essential and complex concept, which occupies a notable significance in competitive strategy entrepreneurial network literature. However, managerial choices play a vital role in the selection of resources. These procedures have posited that dynamic capabilities value realization depends on the conditions of the business environment and organizational knowledge. Indeed, the main reason for the ongoing interests in firms’ dynamic capabilities is the potential influence on firms’ performance. The results of the study are also consistent with Eisenhardt and Martin’s (2000) view as they recognized that dynamic capabilities do not guarantee superior firm performance [

10]. Dynamic capabilities are necessary but not sufficient to maintain sustained advantages to achieve sustainable performance. Firms with excellent abilities would be more likely to meet tough emerging challenges promptly. However, it depends on firms’ ability to respond to meet tough emerging challenges on time though they have equivalent substantive dynamic capabilities. Indeed, different firms face different processes and potential advantages when firms have the abilities to adjust rapidly, reconfigure and change the processes as desired in a competitive business environment. Anand and Vassolo (2008) identified that dynamic capabilities enable the business firm to select better and reliable business partners and structure their network relationships efficiently. Firms’ achieve new knowledge, which improves their sustainable performance [

107]. Teece, Pisano and Shuen (1998) identified that firms’ dynamic capabilities renew firms’ capabilities, which in turn improve performance, especially in competive and dynamic markets [

10,

32]. In an earlier study, Rindova and Kotha (2001) recognized that dynamic capabilities are essential for elevating firms’ managerial capabilities to spot and exploit business opportunities in evolving and competitive environments [

108]. In another study, Daniel and Wilson (2003) recommend that firms’ dynamic capabilities improve the success of firms transformational efforts [

109]. Lee et al. (2002) observed that new sources of competitive benefit lie in small firms’ capability to conceptualize how small firms might cope with competitive environmental changes by recognizing and exploiting business opportunities. These views present the general literature tenor on the significance of firms’ dynamic capabilities to developing and sustaining a competitive business advantage [

110].

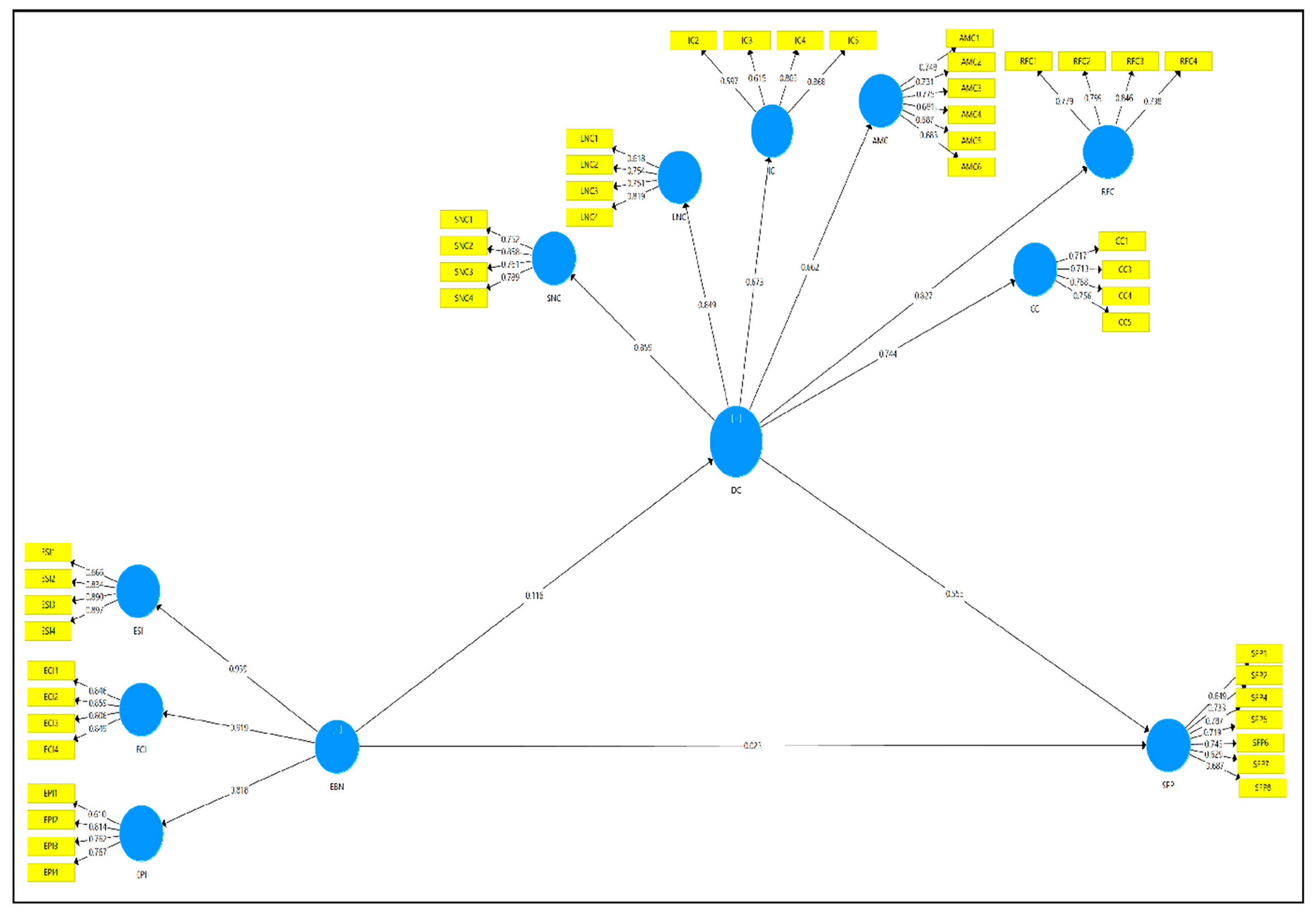

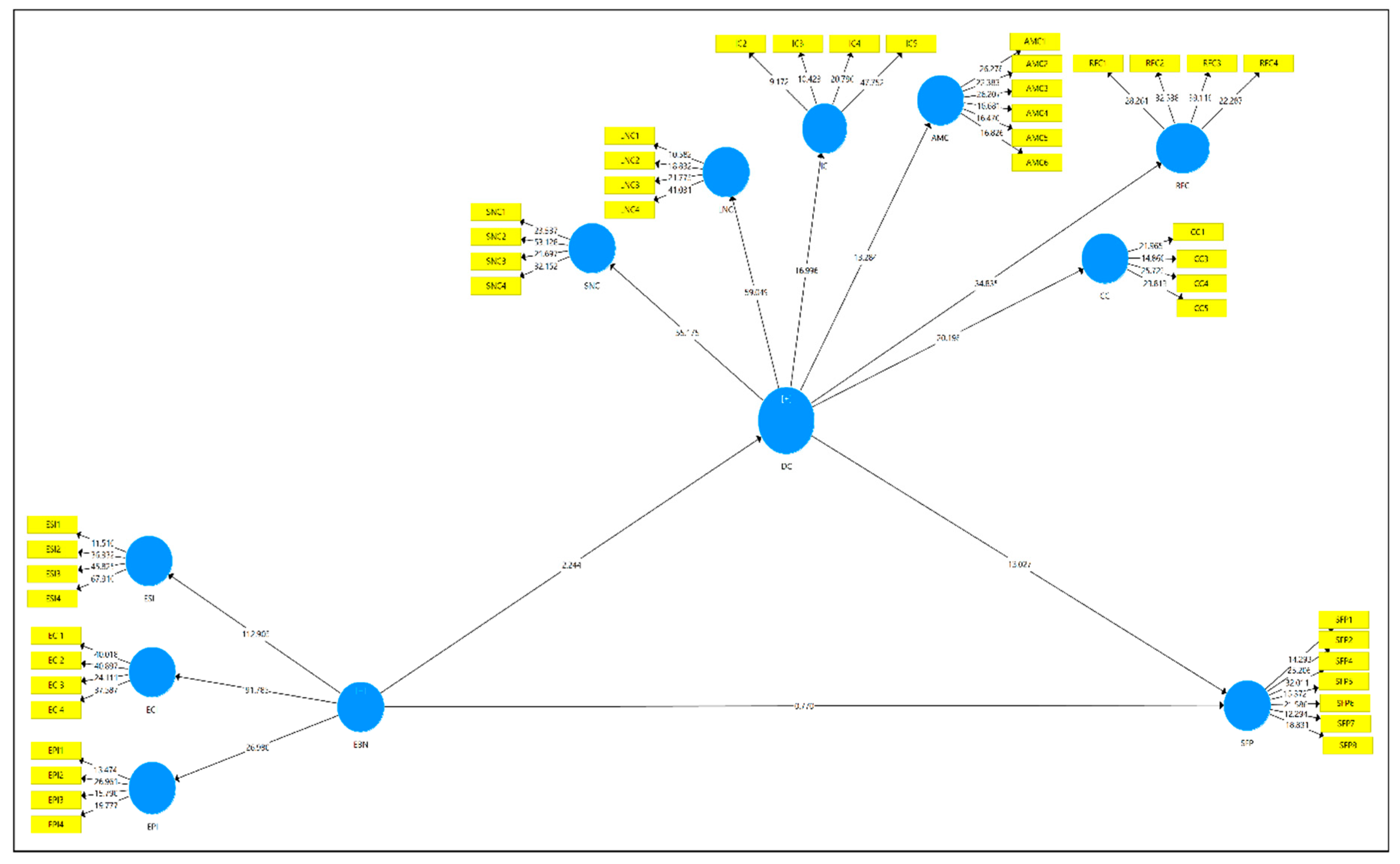

The results of this model specified that the business network is helpful to access and acquire valued resources from the entrepreneurial network resource and it contributes to small firms improved performance. The findings of this study showed that the relationship between the small firm’s performance and entrepreneurial business network (EBN) was not significant. Rao and Singh (2016) and Pavlou and El Sawy (2011) described that the ‘reliability’ of dynamic capabilities measures value should be higher than 0.70 and it will indicate an appropriate level of ‘reliability’ for the construct. [

36,

37]. We selected items from Spillan and Parnell (2006) to measure the sustainable performance of small firms [

80]. Spillan and Parnell (2006) reported that the measures of sustainable performance provided a satisfactory level of validity and reliability [

80]. The measures of alpha coefficient shown reliability value 0.761 and it indicated a reliable, sustainable performance of small firms. In this study, we applied the smart PLS-SEM technique, and through a comprehensive analysis of the structural and measurement models, study results affirmed both models. We implemented an advanced method using PLS-SEM software V-3.2.8, which is a commonly used multivariate analysis approach to calculate and assess the variance-based structural equations models by performing a statistical analysis [

94,

111]. It can test the relationships of a selected model’s latent and manifest variables simultaneously by using measurement and structural models. We designated this technique because of its assessment ability concerning the psychometric properties of each latent construct, determining which the most significant construct is and how it affects sustainable performance [

91,

94].

Table 5 presents the analysis of the structural model of this proposed study. This study argued in Hypothesis 1, “the entrepreneurial business network has a significant positive relationship with a small firm’s sustainable performance”. The findings from this study (see

Table 5) indicated no support for Hypothesis 1 as follows: The entrepreneurial business network (EBN) → small firms performance relationship is not significant in the proposed model of this study as indicated by the results in

Table 5 (β = 0.0232,

t = 0.7698,

p = 0.2209). Thus, findings revealed in this study did not confirm Hypothesis 1 as indicated in

Table 5. Results affirmed that the entrepreneurial business network (EBN) was not positively related to the sustainable performance of small firms’ and statically was not significant at the 5% level (β = 0.0232,

t = 0.7698,

p = 0.2209). Thus, results have not approved Hypothesis 1. This outcome of Hypothesis 1 was in line with the support of previous literature surprisingly because Kregar and Antoncic (2014) and Parker (2018) also viewed the same finding that there was not a significant relationship between the variables of entrepreneurial business network and a small firm’s sustainable performance in their studies [

40,

47].

The plausible explanation of the non-significant relationship between variables of business networks (EBN) and sustainable performance of the small firms’ might be due to business firms entrepreneurial dependency on entrepreneurs’ capabilities. These capabilities are dynamic to combat with the turbulent competitive business environment. It seems that the effect of the entrepreneurial business networks has not shown a direct impact on the small firms’ sustainable performance. However, it could be significant with the indirect effect through other capabilities. In the next stream, to test the mediation effect, the study found a meaningful relationship between the entrepreneurial business network and firms’ dynamic capabilities. Numerous researchers have tried to find the relationship between business networks and a firm’s survival or sustainable performance; however, their studies could not explore such relationships [

50,

51,

52,

53,

54]. Aldrich (1994), Kregar (2014) and other scholars claimed that there was no significant positive relationship between entrepreneurial business networks and firms performance [

39,

40,

55,

56]. Likewise, Golden and Dollinger (1993) and others also could explore the empirical shreds of evidence to prove the relationship between business networks and sustainable performance of firms [

57,

58,

59]. Rare studies observed the ties that entrepreneurial business networks might influence firms’ performance. Thus, this concept is uncertain, equivocal and it requires further investigations to discover the potential impact of entrepreneurial business networks on the firm’s performance. In the next phase, this study examined how dynamic capabilities mediated the relationship between entrepreneurial business networks (EBN) and small firms’ performance.

The study then argued in Hypothesis 2 that dynamic capabilities mediated the relationship between entrepreneurial business networks (EBN) and firms’ sustainable performance, which was a competing hypothesis as compared to Hypothesis 1. Entrepreneurial networks (EBN) → firms’ performance relationship was non-significant (β = 0.0232,

t = 0.7698,

p = 0.2209), while firms’ dynamic capabilities → small firms’ performance exhibited a significant positive relationship (β = 0.1161,

t = 2.2442,

p = 0.0126). Thus, findings of this study confirmed Hypothesis 2, which stated “the entrepreneurial business network has a significant positive relationship with the firm’s dynamic capabilities”. This outcome endorsed that entrepreneurial business networks (EBN) showed a significant positive relationship (

t = 2.2442,

p = 0.0126, <0.05) with dynamic capabilities of small firms. The findings of the study confirmed and supported Hypothesis 2 as it has proved entrepreneurial business networks had a significant positive relationship with the firm’s dynamic capabilities. The findings of Hypothesis 2 was also consistent with the previous study of Eriksson (2014), which described these results and highlighted the outcome that the entrepreneurial business network was antecedent of dynamic capabilities [

75]. Therefore, it has confirmed this statement with empirical evidence. Scholars argued that firms adequately equipped with dynamic capabilities, business firms might reconfigure, build and integrate the available internal resources besides firm-specific external available resources in responding the turbulent and challenging environment [

63,

64], as dynamic capabilities are efficient execution and exploration of new prospects [

65,

66]. The organizational theory, described dynamic capability as the competence of firms to purposefully adopt the available resource base [

67]. In 1997, David Teece, Gary Pisano and Amy Shuen defined this concept that firms’ capabilities to build, integrate, develop and reconfigure its internal/external capabilities to address the rapidly changing competitive business environments. Dynamic capabilities help business firms to react adequately, efficiently and timely to external changes that require a combination of multiple capabilities [

67,

68].

This study argued in Hypothesis 3, which claimed “dynamic capabilities have a significant positive relationship with small firms’ sustainable performance”. Results (β = 0.5546,

t = 13.027,

p = < 0.001) endorsed Hypothesis 3 as indicated in the

Table 5. It also proved that dynamic capabilities (t = 13.027,

p = 0.0000, <0.05) presented a significant positive relationship with sustainable performance of small firms. The findings have confirmed this relationship by endorsing Hypothesis 3. The findings of this study are also consistent with the previous study of Lin and Wu [

74], which provided similar results. Many researchers have argued and debated the significance of dynamic capabilities and explained how business networks get influences on dynamic capabilities [

75,

76,

77]. The entrepreneurial business networks provide a variety of benefits to firms, which, in turn, bring core capabilities to boost up the sustainable performance [

26,

78]. Lin and Wu (2014) described that dynamic capabilities are a transformer of available resources of business firms and typically, firms convert these resources as their tools to achieve enhanced performance [

74].

Finally, Hypothesis 4 stated “dynamic capabilities mediated the relationship between business networks and small firm’s sustainable performance.” The findings of this study confirmed Hypothesis 4 as indicated in

Table 5 (β = 0.0644,

t = 2.095,

p = 0.0181). Thus, Hypothesis 4 exhibited that the dynamic capabilities of small firms mediated the relationship between the entrepreneurial business network (EBN) and sustainable performance of the small business firm. The result of Hypothesis 4 indicated that the mediating impact was significant at the level of 5% (

t = 2.0995,

p = 0.0181, <0.05). This finding of Hypothesis 4 was also in line and consistent with the support of the body of previous literature, interestingly. Based on the existing body of the literature, various scholars have identified firms’ dynamic capabilities as a potent mediator [

21,

79]. The previous literature indicated that firms’ dynamic capabilities could perform a mediating relationship between available resources and sustainable performance [

112]. The plausible explanation of the significant relationship between firms’ dynamic capabilities variable and entrepreneurial business networks and sustainable performance could be in response to business firms’ entrepreneurial reliance on entrepreneurs’ competences. Such capabilities are dynamic to combat with a challenging and competitive environment. It has evidence that firms’ dynamic capabilities have presented a mediating impact on the relationship between entrepreneurial business networks and the sustainable performance of small firms. In this stream, examining the mediation impact, this proposed study explored a significant positive relationship between the entrepreneurial business network and firms’ sustainable performance [

113].

6. Implications

This study has contributed to the existing body of the literature related to the research field of entrepreneurship business network and sustainable performance of small firms in numerous ways. Unlike most of the previous studies explaining the impact of business networks and their relationship with firms’ performance, this study investigated the role of entrepreneurial networks on the sustainable performance of the firms [

105,

114]. This study introduced three variables namely the entrepreneurial business network, firm’s sustainable performance and dynamic capabilities as the mediating variable. The acquisition of a network resource provided an alternative explanation for the deviating outcomes gained from past studies [

115]. Business network improves interaction relationship with business competitors, relationship resources, such as network status, power of resources control, cohesion and trust come from communication and interaction between business industries and other members in the business network. Members of business networks can exchange knowledge, share resources and complement capabilities through business networks [

21,

116]. This outcome is also in line with the explanations of Tseng and Lee (2014), Mahmood (2015) and Lin and Wu (2014), as these studies described that dynamic capabilities (DCs) mediate the relationship significantly between small firms’ valuable resources and sustainable performance of small firms [

72,

74,

79,

104].

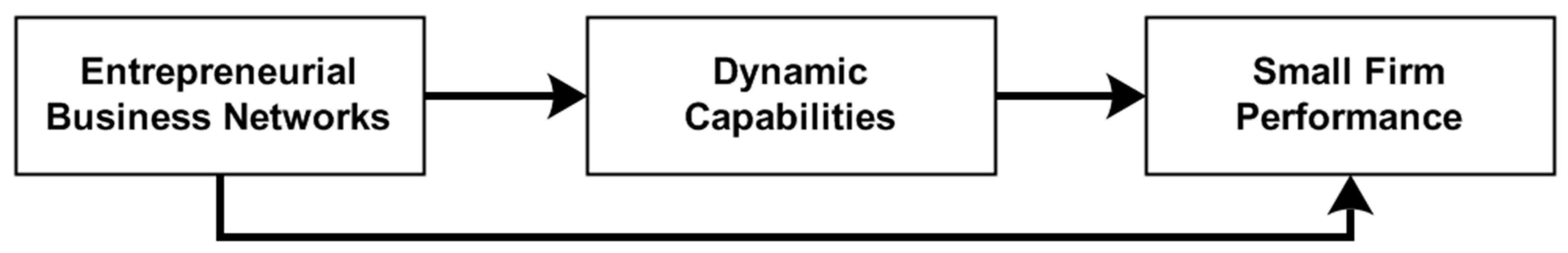

The model of this study in

Figure 1 indicates that the entrepreneurial business network did not prove a direct impact on small firms’ sustainable performance, which provides feedback to entrepreneurial activities choices. However, it has indicated a more complex set of connections among available business opportunities, learning processes, relationships building, developing capabilities and organizational outcomes. The main feature of this research model is that small firms’ dynamic capabilities mediated the relationship between the entrepreneurial business network and sustainable performance of a small firm. This model indicated that implication nature and quality of dynamic capabilities improved performance. The firms’ knowledge stems from available organizational resources and the learning process the venture puts in order early on. When it comes to developing and exploiting available dynamic capabilities, established firms’ and new firms’ ventures might have various types of advantages. However, previous literature has not well cataloged these differences. Future studies can enrich our highlighted understanding of these problems. This understanding might assist us in forming multiple prescriptions for established and new firms. The most broadly held assumption is the malleability of new business ventures’ practices making it easier for small firms’ founders and entrepreneurs to develop new capabilities radically [

117].

The accumulating small firms’ valuable available resources (entrepreneurial business network) and developing small firms’ dynamic capabilities, business companies might refine and enhance competitive advantages. As a result, small firms’ improved their business performance significantly. The significant role of valuable resources and small firms’ dynamic capabilities are interlinked and have revealed the relationship between small firms’ sustainable performance. This model established it on the resource-based view (RBV) besides small firms’ dynamic capabilities view (DCV). This prospective study has fulfilled the ultimate purpose of the theory to accomplish the superior and sustainable performance of small firms. In terms of its contribution to scientific knowledge and novelty, it has contributed to the body of scientific knowledge. It has evaluated both the direct and indirect impact of the entrepreneurial business network (EBN) on small firms’ sustainable performance.

The present study offers many managerial implications to small firms and SMEs operating in Pakistan. The findings showed that entrepreneurial networks inclined to improve the abilities of the small firms to acquire valuable information, business opportunities and resources from surrounding business networks. It might differentiate them from other business networks who do not have this resourceful benefit. The persistent effort and specific role in refining and managing the business network resources acquisition should be in place during the process of strategic planning. Small firms pursue their entrepreneurial initiatives to gain advantages in the competitive business environment. Managers, executive and firms’ owners need to design effective ways to communicate and interact to make their business network more beneficial. They should be aware of an available advantage to develop more resource-based business collaborations. It is essential for small firms operating in a challenging and competitive business environment in emerging economies. They face turbulent situations and experience relatively a shortage of internal resources and competencies [

118,

119]. To enhance the competitive advantage, small firms doing businesses in the emerging economies should acquire and leverage resources across the organizational boundaries to develop the necessary circumstances for their effective exploitation of incoming business opportunities through the entrepreneurial network. The results of this study emphasized the importance of business networks in which small firms enact their available entrepreneurial network posture and develop valuable guidelines for managers, executive and owners on how they might cultivate specific business ties and the configurational combinations. In general, the findings of this study revealed that small firms’ business ties help entrepreneurial businesses to the most efficiently exploit external resources and opportunities for knowledge and technologies.

The practical insinuations of his envisioned study are beneficial for owners and business managers of small firms in Pakistan and the rest of the world. The findings provided a platform of insights to the focused research area and results might help in improving the performance and sustainability of small firms. The findings of this model are advantageous and helpful for small firm owners and managers of the medical sector of Pakistan. They can utilize entrepreneurial business networks properly, and these networks have a positive effect in developing dynamic capabilities of a small firm to enhance sustainable performance. By an overall scenario, the findings of this research study might help managers and small firms’ owners to consider results applications in various emerging and to develop markets around the world. These present markets a majority of small firms and the entrepreneurial business network (EBN) might have a significant impact on small firms’ sustainable performance through small firms’ dynamic capabilities. Correctly, for small and medium-sized firms’ sustainability, these findings might apply to policy-makers and decision-makers to revamp their business design.

7. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study and its structural model have addressed the gap in small business development through an in-depth literature review. We have tested this designed model, examined the effect of the entrepreneurial business network (EBN) on the sustainable performance of small firms. The developed model emphasized to investigate how dynamic capabilities of small firms, mediated the relationship between the entrepreneurial business network and ‘sustainable performance’ of small business firms. The introduction section of this proposed study discussed earlier that small business firms are not performing at satisfactory levels and results found it stagnant. Besides, the existing body of literature recognized that efficient, reliable and dynamic small firms contribute to sustainable economic development. It develops essential improvement by creating a competitive advantage for small firms in a challenging business environment. This research study used the Smart PLS-SEM method, and the results of the structural and measurement models confirmed both models. This study incorporated an advanced approach through the Smart PLS-SEM Version-3.2.8, mostly scholars’ used to perform a multivariate investigation to calculate the variance-based structural equations models by performing a statistical analysis [

94,

111]. This technique is suitable to test relationships of a selected model’s latent and manifest variables simultaneously by using measurement and structural models. We considered this approach because of its assessment capability concerning the psychometric properties of each latent construct, by determining which the most critical construct is and how it affects sustainable performance [

88,

91,

94]. The results of this study provided exciting insights for business managers, decision-makers poly-makers and owners of small and medium-sized firms.

Results did not prove Hypothesis 1 (β = 0.0232,

t = 0.7698,

p = 0.2209), stating that the entrepreneurial business network (EBN) did not show a positive relationship with the sustainable performance of the small firms. Therefore, findings did not confirm Hypothesis 1, stating “the entrepreneurial business network (EBN) has a significant positive relationship with sustainable performance of small firms”. This outcome is in line with earlier studies [

40,

47]. Hypothesis 2 claimed “the entrepreneurial business network has a significant positive relationship with the firm’s dynamic capabilities”. The findings endorsed the significant positive relationship (β = 0.1161,

t = 2.2442,

p = 0.0126), and affirmed Hypothesis 2 of this study. It permitted that the entrepreneurial business network had a significant positive correlation with dynamic capabilities. The results proved it empirically, and findings are consistent with previous literature [

75]. Hypothesis 3 stated “dynamic capabilities have a significant positive relationship with the small firm’s sustainable performance”. The results of this study (β = 0.5546,

t = 13.027,

p = 0.000) proved Hypothesis 3. It also proved that small firms’ dynamic capabilities (

t = 13.027,

p = 0.0000, <0.05) showed a significant positive relationship with the sustainable performance. This result is also consistent with the body of existing literature [

74,

120]. Finally, Hypothesis 4 claimed “dynamic capabilities mediated the relationship between the entrepreneurial business network and small firm’s sustainable performance”. The results of this study (β = 0.0644,

t = 2.095,

p = 0.0181) affirmed Hypothesis 4. Thus, Hypothesis 4 exhibited that the dynamic capabilities of small firms’ mediated the relationship between the entrepreneurial business network and sustainable performance of the small business firms. The results indicated that the mediating impact was significant and confirmed the statement. This finding is also in line with the findings of previous studies [

72,

74,

79,

104,

120,

121,

122]. The accruing small firms’ valuable available resources such as the entrepreneurial business network and dynamic capabilities, small firms’ could improve competitive advantages. This model established the resource-based view (RBV) besides the small firms’ dynamic capabilities view (DCV). This study has addressed the final drive of the theory to achieve sustainable performance. The findings of this study contributed to the body of scientific knowledge. It has assessed both the direct and indirect influence of the entrepreneurial business network on the sustainable performance of the small firms’ operating in the Pakistani manufacturing industry of medical products.