Millennials’ Awareness and Approach to Social Responsibility and Investment—Case Study of the Czech Republic

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Corporate Social Responsibility vs Sustainable and Responsible Investing

2.2. Millennials and Their Approach to Sustainable and Responsible Investing

3. Materials and Methods

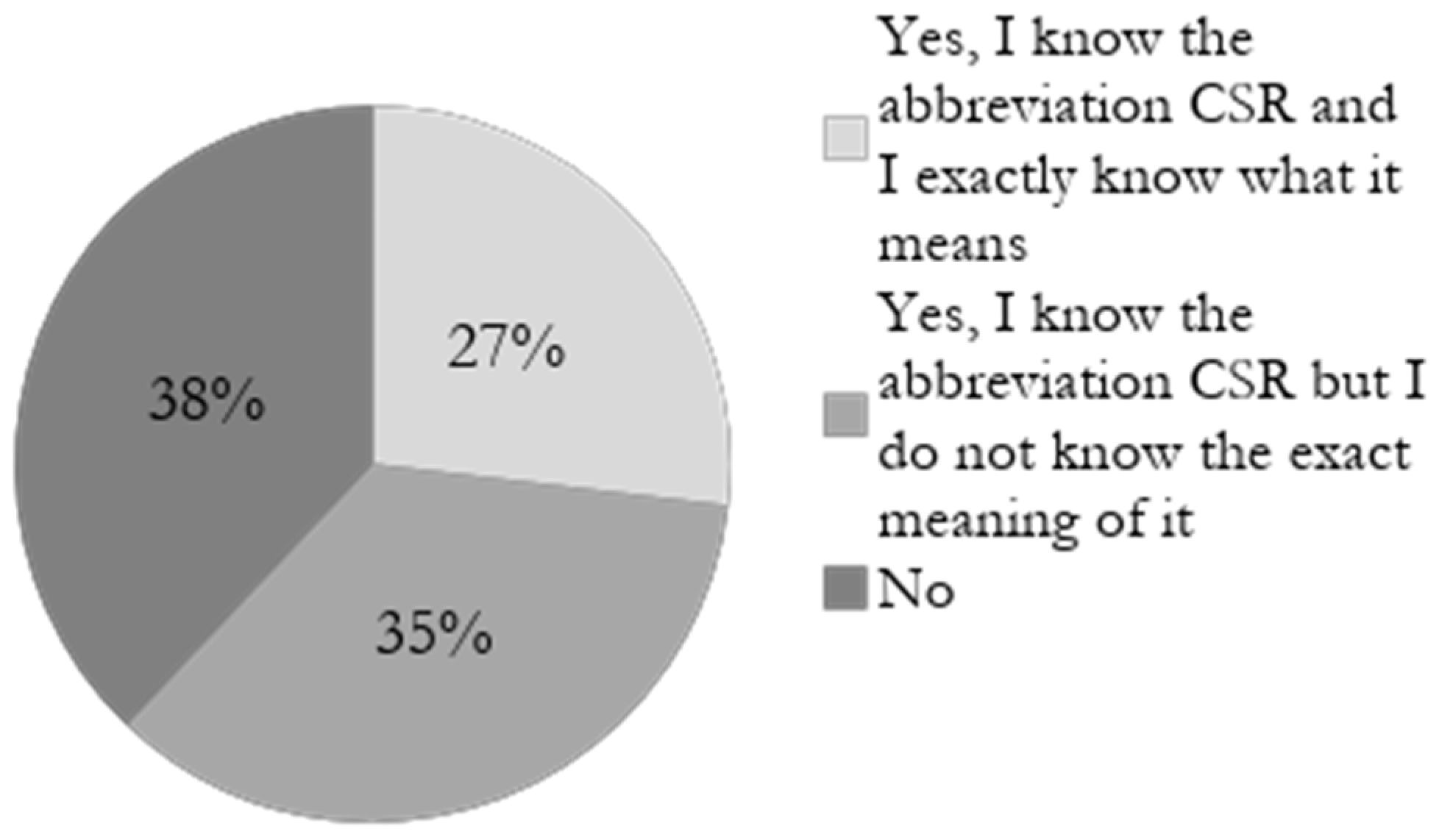

3.1. Research Methodology No.1: The Awareness of the Term CSR

3.1.1. The Sample

3.1.2. Data Collection and Analysis

- RQ1:

- Are the students of economically oriented high education institutions familiar with the term CSR and do they know exactly what it means?

- RQ2:

- Does the level of education influence the awareness of CSR?

- (ΣA)2: Sum of data set A, squared,

- (ΣB)2: Sum of data set B, squared,

- μA: Mean of data set A,

- μB: Mean of data set B,

- ΣA2: Sum of the squares of data set A,

- ΣB2: Sum of the squares of data set B,

- nA: Number of items in data set A,

- nB: Number of items in data set B.

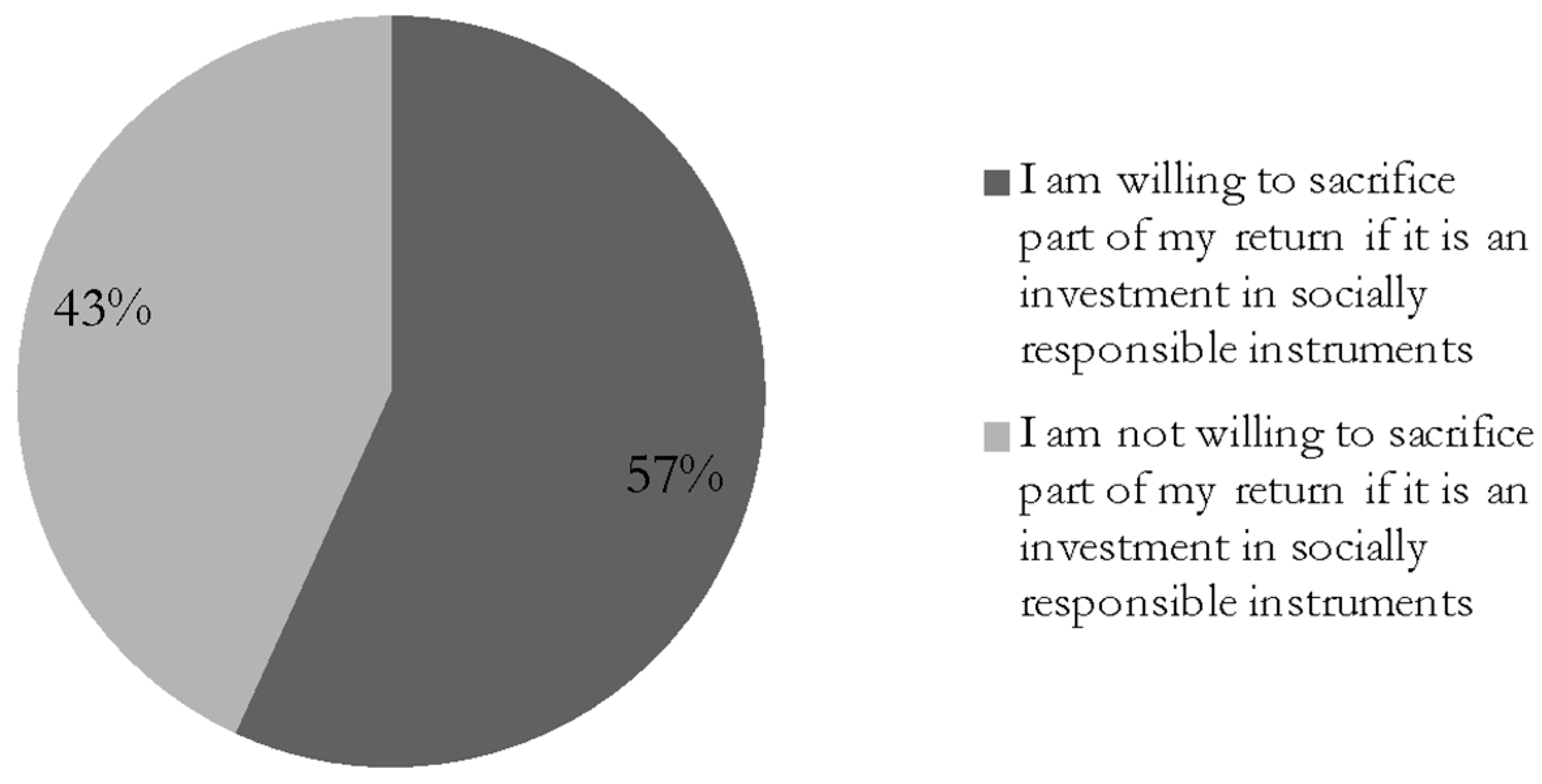

3.2. Research Methodology No.2: The Attitude of Millennials to Sustainable and Responsible Investing

3.2.1. The Sample

3.2.2. Data Collection and Analysis

- RQ1:

- Whether or not the respondents have already considered investing their funds.

- RQ2:

- What criteria for investment decision-making are crucial for them.

- RQ3:

- To what extent is it important for them, when making investment decisions.

- RQ4:

- Whether or not the instrument in which the money is invested (fund, etc.) is sustainable and socially responsible.

- RQ5:

- Whether or not they are willing to risk more in order to achieve a higher return.

- RQ6:

- Whether or not they are willing to sacrifice part of the return if it is an investment in socially responsible instruments.

4. Results

4.1. Millennials’ Awareness of Corporate Social Responsibility

4.2. The Attitude of Millennials to Investing

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Blowfield, M.; Murray, A. Corporate Responsibility; Oxford University Press: Cary, NC, USA, 2011; 431p, ISBN 978-0-19-958107-8. [Google Scholar]

- Pavlík, M.; Bělčík, M. Společenská Odpovědnost Organizace (=Corporate Social Responsibility); Grada Publishing: Praha, Czech Republic, 2010; 176p, ISBN 978-80-247-3157-5. [Google Scholar]

- Otman, J.A. The New Rules of Green Marketing: Strategies, Tools, and Inspiration for Sustainable Branding; Berrett-Koehler Publishers: Oakland, CA, USA, 2011; 272p, ISBN 978-1605098661. [Google Scholar]

- Millennials Drive Growth in Sustainable Investing. Morgan Stanley. 2017. Available online: https://www.morganstanley.com/ideas/sustainable-socially-responsible-investing-millennials-drive-growth (accessed on 31 December 2018).

- Sustainable Signals. New Data from the Individual Investor. Morgan Stanley. Institute for Sustainable Investing. 2017. Available online: https://www.morganstanley.com/pub/content/dam/msdotcom/ideas/sustainable-signals/pdf/Sustainable_Signals_Whitepaper.pdf (accessed on 31 December 2018).

- Sustainable Investing: The Millennial Investor. Key Ernst & Young LLP, 2017. Available online: https://www.ey.com/Publication/vwLUAssets/ey-sustainable-investing-the-millennial-investor-gl/$FILE/ey-sustainable-investing-the-millennial-investor.pdf (accessed on 31 December 2018).

- Marston, C. The Millennials are Coming! The millennials are coming! Investig. Advis. 2016, 36, 48. [Google Scholar]

- Kontio, U.G.; Tapio, P. Four Mexican dreams: What will drive the Mexican millennial to invest? Futures 2017, 93, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Official Website of the Database Web of Science Core Collection. Available online: https://clarivate.com/products/web-of-science/web-science-form/web-science-core-collection/ (accessed on 7 January 2019).

- Bejtkovský, J. Factors influencing the job search and job selection in students of Generation Y in the Czech Republic in the employer branding context. Manag. Mark. 2018, 13, 1133–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimkiewicz, K.; Oltra, V. Does CSR Enhance Employer Attractiveness? The Role of Millennial Job Seekers’ Attitudes. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2017, 24, 449–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catano, V.M.; Hines, H.M. The Influence of Corporate Social Responsibility, Psychologically Healthy Workplaces, and Individual Values in Attracting Millennial Job Applicants. Can. J. Behav. Sci. 2016, 48, 142–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krbova, P.K. Generation Y Attitudes towards Shopping: A Comparison of the Czech Republic and Slovakia. JOC 2016, 8, 38–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Velčovská, Š.; Hadro, D. Generation Y Perceptions and Expectations of Food Quality Labels in the Czech Republic and Poland. Acta Univ. Agric. Silv. Mendel. Brun. 2018, 66, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olšavský, F. Ethnocentrism of Slovak and Czech consumers—Generation Approach. In Proceedings of the Vision 2020: Innovation Management, Development Sustainability, and Competitive Economic Growth, Seville, Spain, 9–10 November 2016; pp. 3458–3466. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, M.S. Corporate Social Responsibility. An Ethical Approach; Broadview Press: Peterborough, ON, Canada, 2011; 176p, ISBN 978-1-55111-294-7. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, H. The Social Responsibilities of the Businessman; University of Iowa Press: Iowa City, IA, USA, 2013; 266p. [Google Scholar]

- Válová, A.; Formánková, S. Corporate Philanthropy in the Czech Republic. Enterp. Compet. Environ. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR). Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/growth/industry/corporate-social-responsibility_en (accessed on 30 December 2018).

- Národní Akční Plán Společenské Odpovědnosti Organizací v České Republice (National Action Plan CSR of Organizations in the Czech Republic). Available online: https://www.mpo.cz/assets/dokumenty/54688/62494/648340/priloha002.pdf (accessed on 30 December 2018).

- Skýpalová, R.; Kučerová, R.; Blašková, V. Development of the Corporate Social Responsibility Concept in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises. Prague Econ. Pap. 2016, 25, 287–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shpak, N.O.; Stanasiuk, N.S.; Hlushko, O.V.; Sroka, W. Assessment of The Social and Labor Components of Industrial Potential in the Context of Corporate Social Responsibility. Pol. J. Manag. Stud. 2018, 17, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmazdogan, O.C.; Seçilmiş, C.; Cicek, D. The Effect of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Perception on Tourism Students’ Intention to Work in Sector. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2015, 23, 1340–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lindgreen, A.; Kotler, P.; Vanhamme, J.; Maon, F. A Stakeholder Approach to Corporate Social Responsibility: Pressures, Conflicts, Reconciliation; Gower Publishing Limited: Aldershot, UK, 2012; 418p, ISBN 978-1-4094-1839-9. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, G.; Joyce, M. Increasing customer loyalty: The impact of corporate social responsibility and corporate image. Ann. Soc. Responsib. 2017, 3, 59–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, D.; Lee, J. The Effects of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Fit and CSR Consistency on Company Evaluation: The Role of CSR Support. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickle, G. Extending the Boundaries: An Assessment of the Integration of Extended Producer Responsibility Within Corporate Social Responsibility. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2015, 26, 112–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Landrum, N.E.; Ohsowski, B. Identifying Worldviews on Corporate Sustainability: A Content Analysis of Corporate Sustainability Reports. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2017, 27, 128–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mohelska, H.; Sokolova, M. Innovative Culture of the Organization and Its Role in the Concept of Corporate Social Responsibility—Czech Republic Case Study. Amfiteatru Econ. 2017, 19, 853–865. [Google Scholar]

- Combs, K. More than just a trend: The importance of impact investing. Corp. Financ. Rev. 2014, 18, 12–18. [Google Scholar]

- Sroka, W.; Szántó, R. Corporate Social Responsibility and Business Ethics in Controversial Sectors: Analysis of Research Results. J. Entrep. Manag. Innov. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lőrinczy, M.; Formánková, S. Business Ethics and CSR in Pharmaceutical Industry in the Czech Republic and Hungary? Acta Univ. Agric. Silvic. Mendel. Brun. 2015, 63, 218–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurská, S.; Válová, A. Corporate social responsibility in mining industry. Acta Univ. Agric. Silv. Mendel. Brun. 2013, 61, 2163–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Woźniak, J.; Pactwa, K. Environmental Activity of Mining Industry Leaders in Poland in Line with the Principles of Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pactwa, K.; Woźniak, J.; Strempski, A. Sustainable Mining—Challenge of Polish Mines. Resour. Policy 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woźniak, J.; Pactwa, K. Responsible Mining—The Impact of the Mining Industry in Poland on the Quality of Atmospheric Air. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliapulios, J. Ohleduplné Fondy Jsou Marketingový Tah, Říká Investor Jan Pravda. Economia a.s. 9 January 2018. Available online: https://archiv.ihned.cz/c1-66011290-ohleduplne-fondy-jsou-marketingovy-tah-rika-investor-jan-pravda (accessed on 8 February 2018).

- Michelson, G.; Wailes, N.; Van Der Laan, S.; Frost, G. Ethical Investment Processes and Outcomes. J. Bus. Ethics 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benn, S.; Bolton, D. Key Concepts in Corporate Social Responsibility; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2011; 246p, ISBN 978-1-84787-929-5. [Google Scholar]

- European SRI Study. 2016. Available online: http://www.eurosif.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/SRI-study-2016-HR.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2018).

- Ballestero, E.; Pérez-Gladish, B.; Garcia-Bernabeu, A. Socially Responsible Investment. A Multi-Criteria Decision Making Approach; Springer International Publishing: Basel, Switzerland, 2015; 301p, ISBN 978-3-319-11835-2. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, J.A. Educating the workforce through CSR: Corporate social responsibility as the key to coordinated workforce improvement. Ann. Soc. Responsib. 2017, 3, 70–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nillson, J. Investment with a conscience: Examining the impact of pro-social attitudes and perceived financial performance on socially responsible behavior. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 83, 307–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohin, T.J. Changing Business from the Inside Out. A Treehugger´s Guide to Working in Corporations; Greenleaf Publishing Limited: Sheffield, UK, 2012; 262p, ISBN 978-1-60994-640-1. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, G.; Feiner, A.; Viehs, M. From the Stockholder to The Stakeholder; Arabesque Partners & University of Oxford: London, UK, 2015; Available online: https://arabesque.com/research/From_the_stockholder_to_the_stakeholder_web.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2018).

- Donovan, W.A. Short History of Socially Responsible Investing. The Balance. 7 February 2018. Available online: https://www.thebalance.com/a-short-history-of-socially-responsible-investing-3025578 (accessed on 13 February 2018).

- 3 Největší Mýty o Sociálně Odpovědném Investování (3 Greatest Myths about Socially Responsible Investing). Investiční web s.r.o. 20 June 2017. Available online: http://www.investicniweb.cz/3-nejvetsi-myty-o-socialne-odpovednem-investovani/ (accessed on 7 February 2018).

- Společensky Odpovědné Investování Získává na Popularitě (Socially Responsible Investing Gains Popularity). Investiční web s.r.o. 9 August 2017. Available online: http://www.investicniweb.cz/spolecensky-odpovedne-investovani-ziskava-na-popularite/ (accessed on 7 February 2018).

- Pactwa, K.; Woźniak, J. Environmental reporting policy of the mining industry leaders in Poland. Resour. Policy 2017, 53, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Česká Spořitelna Nabízí Jako První na Trhu Možnost Penzijního Spoření do Etického Fondu (Česká Spořitelna Offers, Being the First Company on the Market, the Option of Pension Savings into the Ethical Fund). 16 January 2018. Available online: https://www.bankovnipoplatky.com/ceska-sporitelna-nabizi-jako-prvni-na-trhu-moznost-penzijniho-sporeni-do-etickeho-fondu-36264 (accessed on 6 February 2018).

- Vznikl První Český Fond se Zaměřením na Investice se Silným Společenským Dopadem (The First Czech Fund with a Focus on Investments with a Strong Social Impact Was Founded). 2018. Investiční web s.r.o. 27 November 2018. Available online: https://www.investicniweb.cz/news-vznikl-prvni-cesky-fond-se-zamerenim-na-investice-se-silnym-spolecenskym-dopadem/ (accessed on 30 December 2018).

- Index Českého Investora CII750 (Czech Investor INDEX CII750). 2018. Available online: http://www.cii750.cz/InvestorIndex/FS78InvestorIndex/ (accessed on 30 December 2018).

- Čem Musíte Přemýšlet, Než Začnete se Sociálně Odpovědným Investováním (What You Need to Think About to Get Started in Socially Responsible Investing). Investiční web s.r.o. 26 October 2017. Available online: http://www.investicniweb.cz/o-cem-musite-premyslet-nez-zacnete-se-socialne-odpovednym-investovanim/ (accessed on 7 February 2018).

- O’Brian, A.; Liao, L.; Campagna, J. Responsible Investing: Delivering Competitive Performance. Nuveen Investments. 2017. Available online: https://www.tiaa.org/public/pdf/ri_delivering_competitive_performance.pdf (accessed on 9 February 2018).

- Trnková, J. Společenská Odpovědnost Firem: Kompletní Průvodce Tématem & Závěry z Průzkumu v ČR. Business Leaders Forum. 2004. Available online: http://www.Neziskovky.Cz/Data/Vyzkum_CSR_BLF_2004txt8529.Pdf (accessed on 4 February 2018).

- Bauer, R.; Koedijk, K.; Otten, R. International evidence on ethical mutual fund performance and investment style. J. Bank. Financ. 2005, 29, 1751–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Foot, D.K.; Stoffman, D. Boom, Bust and Echo 2000: Profiting from the Demographic Shift in the New Millennium; Macfarlane, Walter & Ross: Toronto, ON, Canada, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Píchová, K.; Janiš, V.; Dřínovská, E.; Lisický, A.; Generation, Y. Attitudes to Future Employment; Mendel University in Brno: Brno, Czech Republic, 2016; p. 43. ISBN 978-80-7509-445-2. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, S.; Todd, S. Acquiring status through the consumption of adventure tourism. In Taking Tourism to the Limits: Issues, Concepts and Managerial Perspectives; Ryan, C., Page, S.J., Aicken, M., Eds.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2005; pp. 149–154. [Google Scholar]

- Karakas, F.; Manisaligil, A.; Sarigollu, E. Management learning at the speed of life: Designing reflective, creative, and collaborative spaces for millennials. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2015, 13, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Griffiths, M.A. Share more, drive less: Millennials value perception and behavioral intent in using collaborative consumption services. J. Consum. Mark. 2017, 34, 132–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede Insights. Available online: https://www.hofstede-insights.com/models/national-culture/ (accessed on 7 January 2019).

- Schewe, C.D.; Debevec, K.; Madden, T.J.; Diamond, W.D.; Parment, A.; Murphy, A. If You’ve Seen One, You’ve Seen Them All! Are Young Millennials the Same Worldwide? J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2013, 25, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crane, A.; Matten, D.; Spence, L. Corporate Social Responsibility: Readings and Cases in Global Context; Routledge: London, UK, 2008; pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Crane, A.; Matten, D. Business Ethics; Oxford University Press: Cary, NC, USA, 2010; 614p, ISBN 978-0-19-956433-0. [Google Scholar]

- Kohlberg, L. Stage and Sequence: The Cognitive Developmental Approach to Socialization. In Handbook of Socialization Theory and Research; Goslin, D., Ed.; Rand McNally: Chicago, IL, USA, 1969; pp. 347–480. [Google Scholar]

- Trevino, L.K. Ethical Decision Making in Organizations: A Person-Situation Interactionist Model. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez-Rodríguez, P.; Galguera, L.; Bravo, M.; Benson, K.; Faff, R.; Pérez-Gladish, B. Profiling Ethical Investors. In Socially Responsible Investment. A Multi-Criteria Decision Making Approach; Springer: Basel, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 23–52. ISBN 978-3-319-11835-2. [Google Scholar]

- Credit Suisse. Impact Investing: Building Bridges across Generations. 26 January 2018. Available online: https://www.credit-suisse.com/corporate/en/articles/news-and-expertise/impact-investing-building-bridges-across-generations-201801.html (accessed on 6 February 2018).

- Umbrela system. Available online: https://umbrela.mendelu.cz (accessed on 17 January 2018).

- Simpson, S.N.I.; Aprim, E.K. Do corporate social responsibility practices of firms attract prospective employees? Perception of university students from a developing country. Int. J. Corp. Soc. Responsib. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plotly. Available online: https://plot.ly/python/t-test (accessed on March–June 2018).

- Statistica.pro. Available online: http://www.statistica.pro (accessed on December 2018–January 2019).

- Aankul, A. T-Test Using Python and Numpy. Towards Data Science. Available online: https://towardsdatascience.com/inferential-statistics-series-t-test-using-numpy-2718f8f9bf2f (accessed on 21 June 2018).

- Stonkute, E.; Vveinhard, J.; Sroka, W. Training the CSR Sensitive Mind-Set: The Integration of CSR into the Training of Business Administration Professionals. Sustainability 2018, 10, 754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adámek, P. Corporate Social Responsibility Education in the Czech Republic. Procedia Soc. Behave. Sci. 2013, 730–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srpová, J.; Kunz, V.; Mísař, J. Applying the Principles of CSR in Enterprises in the Czech Republic. Ekon. Manag. 2012, 6, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Business Leaders Forum. Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) in the Czech Republic: Current Situation and Trends. 2013. Available online: http://reportingcsr.org/force_document.php?fichier=document_861.pdf&fichier_old=CSR_in_the_Czech_Republic_v2.pdf (accessed on 7 February 2018).

- Berényi, L.; Deutsch, N. Changing attitudes of Hungarian business students towards Corporate Social Responsibility. Int. J. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2017, 11, 58–67. [Google Scholar]

- Tormo-Carbó, G.; Seguí-Mas, E.; Oltra, V. Business Ethics as a Sustainability Challenge: Higher Education Implications. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlíková, E.; Šmídová, M. Do We Know the Attitudes of Future Managers and Other Professions? Enterprise and Competitive Environment: Conference Proceedings; Mendelova Univerzita v Brně: Brno, Czech Republic, 2018; pp. 3–12. ISBN 978-80-7509-499-5. Available online: https://ece.pefka.mendelu.cz/sites/default/files/imce/ECE2017_fin.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2018).

- Culiberg, B.; Mihelič, K. Three ethical frames of reference: Insights into Millennials’ ethical judgements and intentions in the workplace. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 25, 94–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The 2006 Millennial Cause Study. The Millennial Generation: Pro-Social and Empowered to Change the World. 2006. Available online: http://www.centerforgiving.org/Portals/0/2006%20Cone%20Millennial%20Cause%20Study.pdf (accessed on 30 December 2018).

- Pironon, J. The Millennials Generation in the Working Environment. Innovation & Knowledge: Society. 21 September 2016. Available online: https://www.ipsos.com/en/millennials-generation-working-environment (accessed on 30 December 2018).

- Pružinová, K. Mileniálové Chtějí Vidět Dopad Své Práce. Musel Jsem se s Nimi Naučit Pracovat, Říká Šéf Marketingu v Googlu Petr Šmíd. (The Milenials Want to See the Impact of Their Work. I Had to Learn How to Work with Them, Says Petr Šmíd, Head of Marketing in Google). Hospodářské Noviny. 5 October 2018. Available online: https://byznys.ihned.cz/c1-66275920-milenialove-chteji-videt-dopad-sve-prace-musel-jsem-se-s-nimi-naucit-pracovat-rika-sef-marketingu-v-googlu-petr-smid (accessed on 30 December 2018).

- Bonadonna, A.; Giachino, C.; Truant, E. Sustainability and Mountain Tourism: The Millennial’s Perspective. Sustainabillity 2017, 9, 1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Rodríguez, M.R.; Díaz-Fernández, M.C.; Pawlak, M.; Simonetti, B. Perceptions of students university of corporate social responsibility. Qual. Quant. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The 2016 Deloitte Millennial Survey Winning over the Next Generation of Leaders. Available online: https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/global/Documents/About-Deloitte/gx-millenial-survey-2016-exec-summary.pdf (accessed on 31 December 2018).

- Larson, L.R.L.; Eastman, J.K.; Bock, D.E. A Multi-Method Exploration of the Relationship between Knowledge and Risk: The Impact on Millennials’ Retirement Investment Decisions. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debevec, K.; Schewe, C.D.; Madden, T.J.; Diamond, W.D. Are Today’s Millennials Splintering into a New Generational Cohort? Maybe. J. Consum. Behav. 2013, 12, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, K.; Johanson, G. Research Methods. Information, Systems, and Contexts; Chandos Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2018; 622p, ISBN 9780081022207. [Google Scholar]

- Gulavani, S.; Nayak, N.; Nayak, M. CSR in Higher Education. J. Bus. Manag. 2016, 18, 37–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viederman, S. Barriers to Sustainable Investing. In Evolutions in Sustainable Investing; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 211–215. ISBN 978-0-470-88849-0. [Google Scholar]

- Hoefel, F.; Francis, T. ‘True Gen’: Generation Z and Its Implications for Companies. 2018. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/consumer-packaged-goods/our-insights/true-gen-generation-z-and-its-implications-for-companies (accessed on 31 December 2018).

| Key Words | Number of Issues Found | Relevant | Irrelevant | Number of Issues Written in the Czech Republic |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Millennial | 2083 | 452 | 1631 | 0 |

| Millennial + behavior | 192 | 98 | 94 | 0 |

| Millennial + investing | 7 | 1 | 6 | 0 |

| Millennial + investment | 12 | 2 | 10 | 0 |

| Millennial + social responsibility | 21 | 5 | 16 | 0 |

| Millennial + CSR | 8 | 5 | 3 | 0 |

| Millennial + Czech Republic | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Generation Y + social responsibility | 21 | 4 | 17 | 1 |

| Generation Y + invest | 7 | 2 | 5 | 0 |

| Generation Y + CSR | 6 | 1 | 5 | 1 |

| Generation Y + Czech Republic | 21 | 8 | 13 | 20 |

| Sequence | Criterion |

|---|---|

| 1 | Expected return |

| 2–3 | Guaranteed rate of return |

| 2–3 | Rate of loss risk |

| 4 | Return-to-loss ratio |

| 5 | Whether or not the investment is time-limited, or whether there is the option of immediate withdrawal of funds |

| 6 | Whether or not my funds are invested in investment instruments that do not affect society and the environment negatively (tobacco industry, alcohol, etc.) |

| 7 | Maximum possibility of fund control and handling (“I want to manage everything myself”) |

| 8 | Whether or not my funds are invested in socially responsible and sustainable instruments (i.e., in funds preventing negative impact on society and promoting socially responsible activities) |

| 9 | Services provided by an investment intermediary (“I do not have to worry about anything”) |

| H0 | t-test | Statistic = −1.6528 | p-Value = 0.099 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Formánková, S.; Trenz, O.; Faldík, O.; Kolomazník, J.; Sládková, J. Millennials’ Awareness and Approach to Social Responsibility and Investment—Case Study of the Czech Republic. Sustainability 2019, 11, 504. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11020504

Formánková S, Trenz O, Faldík O, Kolomazník J, Sládková J. Millennials’ Awareness and Approach to Social Responsibility and Investment—Case Study of the Czech Republic. Sustainability. 2019; 11(2):504. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11020504

Chicago/Turabian StyleFormánková, Sylvie, Oldřich Trenz, Oldřich Faldík, Jan Kolomazník, and Jitka Sládková. 2019. "Millennials’ Awareness and Approach to Social Responsibility and Investment—Case Study of the Czech Republic" Sustainability 11, no. 2: 504. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11020504