Canadian Prostate Cancer Trends in the Context of PSA Screening Guideline Changes

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Results

3.1. Age-Standardized Trends

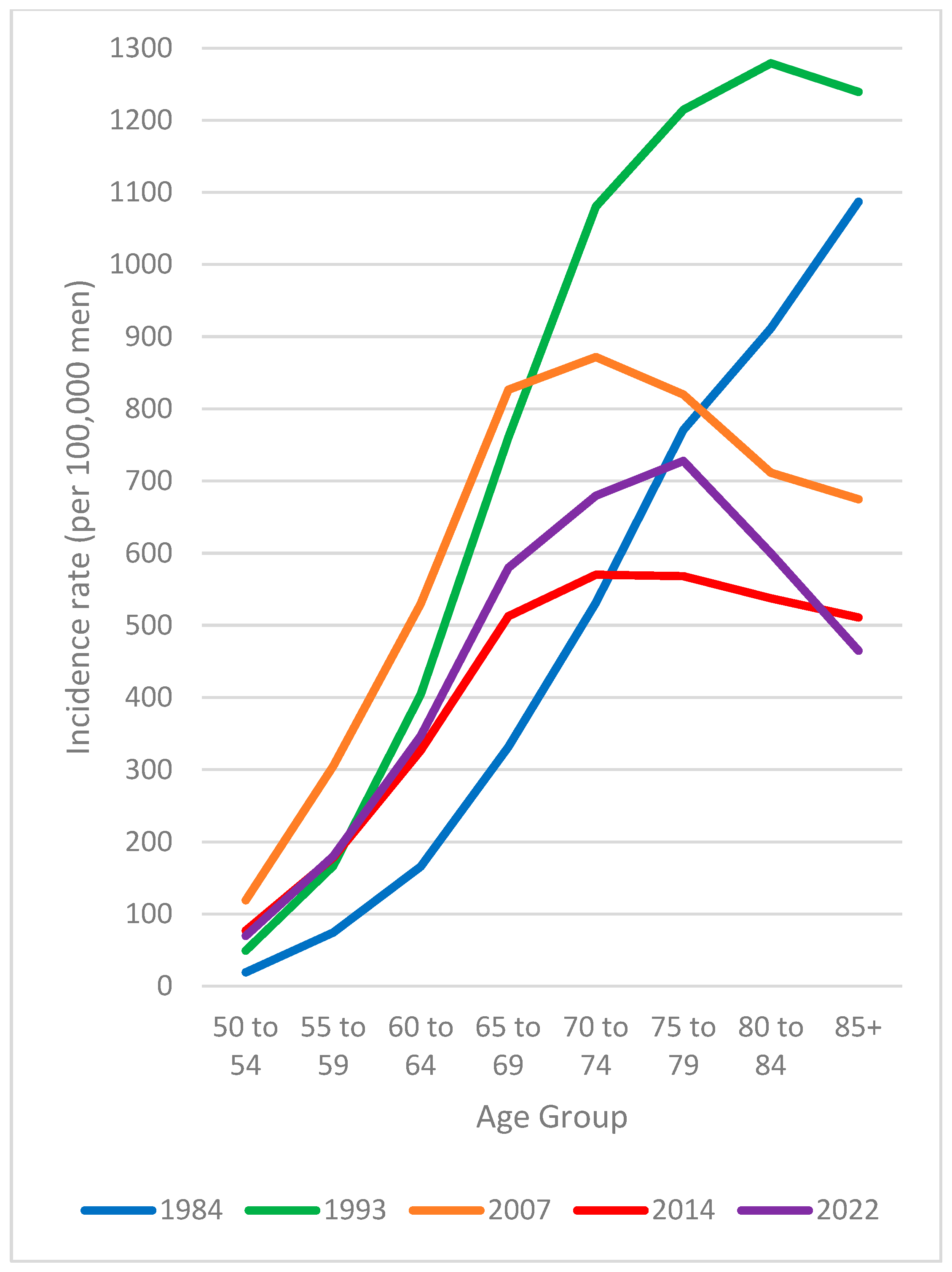

3.2. Age-Specific Trends

3.3. Age-Specific Rate Patterns over Time

3.4. Stage Trends

3.5. Net Survival Trends

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brenner, D.R.; Gillis, J.; Demers, A.A.; Ellison, L.F.; Billette, J.-M.; Zhang, S.X.; Liu, J.L.; Woods, R.R.; Finley, C.; Fitzgerald, N.; et al. Projected estimates of cancer in Canada in 2024. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2024, 196, E615–E623, Correction in Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2024, 196, E890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eastham, J.A.; Auffenberg, G.B.; Barocas, D.A.; Chou, R.; Crispino, T.; Davis, J.W.; Eggener, S.; Horwitz, E.M.; Kane, C.J.; Kirkby, E.; et al. Clinically Localized Prostate Cancer: AUA/ASTRO Guideline, Part I: Introduction, Risk Assessment, Staging, and Risk-Based Management. J. Urol. 2022, 208, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eastham, J.A.; Auffenberg, G.B.; Barocas, D.A.; Chou, R.; Crispino, T.; Davis, J.W.; Eggener, S.; Horwitz, E.M.; Kane, C.J.; Kirkby, E.; et al. Clinically Localized Prostate Cancer: AUA/ASTRO Guideline. Part III: Principles of Radiation and Future Directions. J. Urol. 2022, 208, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristea, O.; Lavallée, L.T.; Montroy, J.; Stokl, A.; Cnossen, S.; Mallick, R.; Fergusson, D.; Momoli, F.; Cagiannos, I.; Morash, C.; et al. Active surveillance in Canadian men with low-grade prostate cancer. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2016, 188, E141–E147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- McAlpine, K.; Forster, A.J.; Breau, R.H.; McIsaac, D.; Tufts, J.; Mallick, R.; Cagiannos, I.; Morash, C.; Lavallée, L.T. Robotic surgery improves transfusion rate and perioperative outcomes using a broad implementation process and multiple surgeon learning curves. Can. Urol. Assoc. J. 2018, 13, 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, D.-D.; Lofters, A.; Wallis, C.J.; Zlotta, A.R.; Fleshner, N.E.; Trinh, Q.-D.; Finelli, A.; Rosella, L.C.; Detsky, A.S.; Roobol, M.J.; et al. Is it time for Canada to revisit its approach to prostate cancer screening? Lancet Reg. Health Am. 2025, 49, 101180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tolis, G.; Ackman, D.; Stellos, A.; Mehta, A.; Labrie, F.; Fazekas, A.T.; Comaru-Schally, A.M.; Schally, A.V. Tumor growth inhibition in patients with prostatic carcinoma treated with luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone agonists. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1982, 79, 1658–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bono, J.S.; Oudard, S.; Ozguroglu, M.; Hansen, S.; Machiels, J.-P.; Kocak, I.; Gravis, G.; Bodrogi, I.; Mackenzie, M.J.; Shen, L.; et al. Prednisone plus cabazitaxel or mitoxantrone for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer progressing after docetaxel treatment: A randomised open-label trial. Lancet 2010, 376, 1147–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scher, H.I.; Fizazi, K.; Saad, F.; Taplin, M.-E.; Sternberg, C.N.; Miller, K.; De Wit, R.; Mulders, P.; Chi, K.N.; Shore, N.D.; et al. Increased Survival with Enzalutamide in Prostate Cancer after Chemotherapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 367, 1187–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bono, J.S.; Logothetis, C.J.; Molina, A.; Fizazi, K.; North, S.; Chu, L.; Chi, K.N.; Jones, R.J.; Goodman, O.B.; Saad, F.; et al. Abiraterone and Increased Survival in Metastatic Prostate Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 1995–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartor, O.; De Bono, J.; Chi, K.N.; Fizazi, K.; Herrmann, K.; Rahbar, K.; Tagawa, S.T.; Nordquist, L.T.; Vaishampayan, N.; El-Haddad, G.; et al. Lutetium-177–PSMA-617 for Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 1091–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, C.; Nilsson, S.; Heinrich, D.; Helle, S.I.; O’Sullivan, J.M.; Fosså, S.D.; Chodacki, A.; Wiechno, P.; Logue, J.; Seke, M.; et al. Alpha Emitter Radium-223 and Survival in Metastatic Prostate Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bono, J.; Mateo, J.; Fizazi, K.; Saad, F.; Shore, N.; Sandhu, S.; Chi, K.N.; Sartor, O.; Agarwal, N.; Olmos, D.; et al. Olaparib for Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 2091–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, P.C.; Donker, P.J. Impotence Following Radical Prostatectomy: Insight Into Etiology and Prevention. J. Urol. 1982, 128, 492–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulati, R.; Tsodikov, A.; Wever, E.M.; Mariotto, A.B.; Heijnsdijk, E.A.M.; Katcher, J.; De Koning, H.J.; Etzioni, R. The impact of PLCO control arm contamination on perceived PSA screening efficacy. Cancer Causes Control. 2012, 23, 827–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsodikov, A.; Gulati, R.; Heijnsdijk, E.A.M.; Pinsky, P.F.; Moss, S.M.; Qiu, S.; De Carvalho, T.M.; Hugosson, J.; Berg, C.D.; Auvinen, A.; et al. Reconciling the Effects of Screening on Prostate Cancer Mortality in the ERSPC and PLCO Trials. Ann. Intern. Med. 2017, 167, 449–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröder, F.H.; Hugosson, J.; Roobol, M.J.; Tammela, T.L.J.; Zappa, M.; Nelen, V.; Kwiatkowski, M.; Lujan, M.; Määttänen, L.; Lilja, H.; et al. Screening and prostate cancer mortality: Results of the European Randomised Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC) at 13 years of follow-up. Lancet 2014, 384, 2027–2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alpert, P.F. New Evidence for the Benefit of Prostate-specific Antigen Screening: Data From 400,887 Kaiser Permanente Patients. Urology 2018, 118, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hugosson, J.; Carlsson, S.; Aus, G.; Bergdahl, S.; Khatami, A.; Lodding, P.; Pihl, C.-G.; Stranne, J.; Holmberg, E.; Lilja, H. Mortality results from the Göteborg randomised population-based prostate-cancer screening trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010, 11, 725–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hugosson, J.; Roobol, M.J.; Månsson, M.; Tammela, T.L.J.; Zappa, M.; Nelen, V.; Kwiatkowski, M.; Lujan, M.; Carlsson, S.V.; Talala, K.M.; et al. European Study of Prostate Cancer Screening—23-Year Follow-up. N. Engl. J. Med. 2025, 393, 1669–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoag, J.E.; Nyame, Y.A.; Gulati, R.; Etzioni, R.; Hu, J.C. Reconsidering the Trade-offs of Prostate Cancer Screening. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 2465–2468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rencsok, E.M.; Bazzi, L.A.; McKay, R.R.; Huang, F.W.; Friedant, A.; Vinson, J.; Peisch, S.; Zarif, J.C.; Simmons, S.; Hawthorne, K.; et al. Diversity of Enrollment in Prostate Cancer Clinical Trials: Current Status and Future Directions. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark. Prev. 2020, 29, 1374–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otiono, K.; Nkonge, B.; Olaiya, O.R.; Pierre, S. Prostate cancer screening in Black men in Canada: A case for risk-stratified care. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2022, 194, E1411–E1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, P.W.; Cousins, M.M.; Tsodikov, A.; Soni, P.D.; Crook, J.M. Mortality reduction and cumulative excess incidence (CEI) in the prostate-specific antigen (PSA) screening era. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 5810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamey, T.A.; Yang, N.; Hay, A.R.; McNeal, J.E.; Freiha, F.S.; Redwine, E. Prostate-Specific Antigen as a Serum Marker for Adenocarcinoma of the Prostate. N. Engl. J. Med. 1987, 317, 909–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalona, W.J.; Smith, D.S.; Ratliff, T.L.; Dodds, K.M.; Coplen, D.E.; Yuan, J.J.J.; Petros, J.A.; Andriole, G.L. Measurement of Prostate-Specific Antigen in Serum as a Screening Test for Prostate Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 1991, 324, 1156–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, R.J.; Marzouk, K.; Finelli, A.; Saad, F.; So, A.I.; Violette, P.D.; Breau, R.H.; Rendon, R.A. UPDATE—2022 Canadian Urological Association recommendations on prostate cancer screening and early diagnosis: Endorsement of the 2021 Cancer Care Ontario guidelines on prostate multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging. Can. Urol. Assoc. J. 2022, 16, E184–E196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, N.; Gorber, S.C.; Shane, A.; Joffres, M.; Singh, H.; Dickinson, J.; Shaw, E.; Dunfield, L.; Tonelli, M. Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care Recommendations on screening for prostate cancer with the prostate-specific antigen test. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2014, 186, 1225–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyer, V.A.; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for Prostate Cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 2012, 157, 120–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Preventive Services Task Force; Grossman, D.C.; Curry, S.J.; Owens, D.K.; Bibbins-Domingo, K.; Caughey, A.B.; Davidson, K.W.; Doubeni, C.A.; Ebell, M.; Epling, J.W.; et al. Screening for Prostate Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA 2018, 319, 1901, Correction in JAMA 2018, 320, 2483. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.7453.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witherspoon, L.; Breau, R.H.; Lavallée, L.T. Evidence-based approach to active surveillance of prostate cancer. World J. Urol. 2020, 38, 555–562, Erratum in World J. Urol. 2020, 38, 563–564. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00345-019-03048-3.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moosavi, B.; Flood, T.A.; Al-Dandan, O.; Breau, R.H.; Cagiannos, I.; Morash, C.; Malone, S.C.; Schieda, N. Multiparametric MRI of the anterior prostate gland: Clinical–radiological–histopathological correlation. Clin. Radiol. 2016, 71, 405–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavallée, L.T.; Binette, A.; Witiuk, K.; Cnossen, S.; Mallick, R.; Fergusson, D.A.; Momoli, F.; Morash, C.; Cagiannos, I.; Breau, R.H. Reducing the Harm of Prostate Cancer Screening: Repeated Prostate-Specific Antigen Testing. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2016, 91, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchir, D.; Farag, M.; Szafron, M. Prostate specific antigen (PSA) screening rates and factors associated with screening in Eastern Canadian men: Findings from cross-sectional survey data. Can. Urol. Assoc. J. 2020, 14, E319–E327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, T.M.; Lau, E.; Newell, K.J. Implications of prostate-specific antigen screening guidelines on clinical practice at a Canadian regional community hospital. Can. Urol. Assoc. J. 2017, 11, 283–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jemal, A.; Fedewa, S.A.; Ma, J.; Siegel, R.; Lin, C.C.; Brawley, O.; Ward, E.M. Prostate Cancer Incidence and PSA Testing Patterns in Relation to USPSTF Screening Recommendations. JAMA 2015, 314, 2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presti, J.; Alexeeff, S.; Horton, B.; Prausnitz, S.; Avins, A.L. Changes in Prostate Cancer Presentation Following the 2012 USPSTF Screening Statement: Observational Study in a Multispecialty Group Practice. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2020, 35, 1368–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, L.; Aldrighetti, C.M.; Ghosh, A.; Niemierko, A.; Chino, F.; Huynh, M.J.; Efstathiou, J.A.; Kamran, S.C. Association of the USPSTF Grade D Recommendation Against Prostate-Specific Antigen Screening With Prostate Cancer–Specific Mortality. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2211869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, J.; Shane, A.; Tonelli, M.; Gorber, S.C.; Joffres, M.; Singh, H.; Bell, N. Trends in prostate cancer incidence and mortality in Canada during the era of prostate-specific antigen screening. CMAJ Open 2016, 4, E73–E79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Canada Canadian Cancer Registry 1992 to 2022. Available online: https://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p2SV.pl?Function=getSurvey&Id=1556562 (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- Fritz, A.; Percy, C.; Jack, A.; Shanmugaratnam, K.; Sobin, L.; Parkin, D.; Whelan, S. International Classification of Disease for Oncology, 3rd ed.; First Revision; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Diseases; Ninth Revision; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1977; Volumes 1 and 2. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada Canadian Vital Statistics—Death Database (CVS: D). Available online: https://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p2SV.pl?Function=getSurvey&Id=1568395 (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- World Health Organization. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems; Tenth Revision; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1992; Volumes 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada Annual Demographic Estimates: Canada, Provinces and Territories 2024. Available online: https://publications.gc.ca/site/archivee-archived.html?url=https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2024/statcan/91-215-x2024001-eng.pdf (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- Brisson, J.; Pelletier, E. Evaluation of the Completeness of the Fichier des Tumeurs du Québec. Available online: https://www.inspq.qc.ca/sites/default/files/publications/254-evaluationcompletenessfichiertumeurs.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Canadian Cancer Statistics Advisory Committee in Collaboration with the Canadian Cancer Society, Statistics Canada and the Public Health Agency of Canada. Canadian Cancer Statistics 2023; Canadian Cancer Society: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2023. Available online: https://cdn.cancer.ca/-/media/files/research/cancer-statistics/2023-statistics/2023_PDF_EN.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Canadian Cancer Statistics Advisory Committee in Collaboration with the Canadian Cancer Society, Statistics Canada and the Public Health Agency of Canada. Canadian Cancer Statistics 2025; Canadian Cancer Society: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2025. Available online: http://cancer.ca/Canadian-Cancer-Statistics-2025-EN (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Joinpoint Regression Program, Version 5.2.0.0. Statistical Methodology and Applications Branch, Surveillance Research Program. National Cancer Institute: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2024.

- Kim, H.-J.; Fay, M.P.; Feuer, E.J.; Midthune, D.N. Permutation tests for joinpoint regression with applications to cancer rates. Stat. Med. 2000, 19, 335–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Canada. 12. Canadian Cancer Registry–Standard Population Used for Age-Standardization. Available online: https://www.statcan.gc.ca/en/statistical-programs/document/3207_D12_V5 (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- Edge, S.B.; Byrd, D.R.; Compton, C.C.; Fritz, A.G.; Greene, F.L.; Trotti, A. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 7th ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Edge, S.; Compton, C.C. The American Joint Committee on Cancer: The 7th edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual and the future of TNM. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2010, 17, 1471–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, M.B.; Edge, S.B.; Greene, F. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 8th ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison, L.F.; Saint-Jacques, N. Five-year cancer survival by stage at diagnosis in Canada. Health Rep. 2023, 34, 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada Social Data Linkage Environment. Available online: https://www.statcan.gc.ca/eng/sdle/index (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- Statistics Canada Life tables, Canada, Provinces and Territories 1980/1982 to 2021/2023 (Three-Year Estimates), and 1980 to 2023 (Single-Year Estimates) (Catalogue No. 84-537-X). Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/84-537-x/84-537-x2024001-eng.pdf (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- Statistics Canada. Special Request Tabulation Completed by Demography Division; Statistics Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison, L.F. Adjusting relative survival estimates for cancer mortality in the general population. Health Rep. 2014, 25, 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- Talbäck, M.; Dickamn, P.W. Estimating expected survival probabilities for relative survival analysis—Exploring the impact of including cancer patient mortality in the calculations. Eur. J. Cancer 2011, 47, 2626–2632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickman, P.W. Estimating and Modelling Relative Survival Using SAS. Available online: http://www.pauldickman.com/software/sas (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- Pohar, M.P.; Stare, J.; Estève, J. On estimation in relative survival. Biometrics 2012, 68, 113–120. [Google Scholar]

- Life Table Methods. Available online: https://github.com/FlexSurv/repo (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- Ellison, L.F. An empirical evaluation of period survival analysis using data from the Canadian Cancer Registry. Ann. Epidemiol. 2006, 16, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.C.; Nguyen, P.; Mao, J.; Halpern, J.; Shoag, J.; Wright, J.D.; Sedrakyan, A. Increase in Prostate Cancer Distant Metastases at Diagnosis in the United States. JAMA Oncol. 2017, 3, 705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kratzer, T.B.; Mazzitelli, N.; Star, J.; Dahut, W.L.; Jemal, A.; Siegel, R.L. Prostate cancer statistics, 2025. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2025, 75, 485–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howlader, N.; Bhattacharya, M.; Scoppa, S.; Miller, D.; Noone, A.-M.; Negoita, S.; Cronin, K.; Mariotto, A. Cancer and COVID-19: US cancer incidence rates during the first year of the pandemic. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2024, 116, 208–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, A.N. Mitigating COVID-19’s impact on missed and delayed cancer diagnoses. Can. Fam. Physician 2022, 68, 323–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negoita, S.; Mariotto, A.; Benard, V.; Kohler, B.A.; Jemal, A.; Penberthy, L. Reply to Annual Report to the Nation on the status of cancer, part II: Recent changes in prostate cancer trends and disease characteristics. Cancer 2019, 125, 318–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, S.S.; Muralidhar, V.; Zhao, S.G.; Sanford, N.N.; Franco, I.; Fullerton, Z.H.; Chavez, J.; D’Amico, A.V.; Feng, F.Y.; Rebbeck, T.R.; et al. Prostate cancer incidence across stage, NCCN risk groups, and age before and after USPSTF Grade D recommendations against prostate-specific antigen screening in 2012. Cancer 2020, 126, 717–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, D.A.; O’Neil, M.E.; Richards, T.B.; Dowling, N.F.; Weir, H.K. Prostate Cancer Incidence and Survival, by Stage and Race/Ethnicity—United States, 2001–2017. Mmwr Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020, 69, 1473–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Lu, B.; He, M.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Du, L. Prostate Cancer Incidence and Mortality: Global Status and Temporal Trends in 89 Countries From 2000 to 2019. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 811044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potosky, A.L.; Kessier, L.; Gridley, G.; Brown, C.C.; Horm, J.W. Rise in prostatic Cancer Incidence Associated With Increased Use of Transurethral Resection. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1990, 82, 1624–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, J.-E. Natural History of Early, Localized Prostate Cancer. JAMA 2004, 291, 2713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etzioni, R.; Tsodikov, A.; Mariotto, A.; Szabo, A.; Falcon, S.; Wegelin, J.; diTommaso, D.; Karnofski, K.; Gulati, R.; Penson, D.F.; et al. Quantifying the role of PSA screening in the US prostate cancer mortality decline. Cancer Causes Control. 2008, 19, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napoli, G.; Arcangeli, S.; Fionda, B.; Munoz, F.; Tebano, U.; Durante, E.; Tucci, M.; Bortolus, R.; Muraro, M.; Rinaldi, G.; et al. A Systematic Review and a Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials’ Control Groups in Metastatic Hormone-Sensitive Prostate Cancer (mHSPC). Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2022, 24, 1633–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulati, R.; Inoue, L.Y.T.; Gore, J.L.; Katcher, J.; Etzioni, R. Individualized Estimates of Overdiagnosis in Screen-Detected Prostate Cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2014, 106, djt367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ankerst, D.P.; Tangen, C.M.; Thompson, I.M. Prostate Cancer Screening; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Gulati, R.; Gore, J.L.; Etzioni, R. Comparative Effectiveness of Alternative Prostate-Specific Antigen–Based Prostate Cancer Screening Strategies: Model Estimates of Potential Benefits and Harms. Ann. Intern. Med. 2013, 158, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björnebo, L.; Discacciati, A.; Abbadi, A.; Falagario, U.G.; Engel, J.C.; Vigneswaran, H.T.; Jäderling, F.; Grönberg, H.; Eklund, M.; Lantz, A.; et al. Prostate-specific Antigen Density as a Selection Tool Before Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Prostate Cancer Screening: An Analysis from the STHLM3MRI Randomized Clinical Trial. Eur. Urol. Focus 2025, 29, S2405456925001750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasivisvanathan, V.; Rannikko, A.S.; Borghi, M.; Panebianco, V.; Mynderse, L.A.; Vaarala, M.H.; Briganti, A.; Budäus, L.; Hellawell, G.; Hindley, R.G.; et al. MRI-Targeted or Standard Biopsy for Prostate-Cancer Diagnosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 1767–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hugosson, J.; Månsson, M.; Wallström, J.; Axcrona, U.; Carlsson, S.V.; Egevad, L.; Geterud, K.; Khatami, A.; Kohestani, K.; Pihl, C.-G.; et al. Prostate Cancer Screening with PSA and MRI Followed by Targeted Biopsy Only. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 387, 2126–2137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandara, N.A.; Vethanayagam, R.; Kim, S.; St-Laurent, M.-P.; Black, P.C.; Mannas, M. Navigating prostate cancer screening in Canada for marginalized men through PSA screening and guidelines adherence: A call to action for policymakers. Can. Urol. Assoc. J. 2024, 18, E291–E294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiciak, A.; Clark, W.; Uhlich, M.; Letendre, A.; Littlechild, R.; Lightning, P.; Vasquez, C.; Singh, R.; Broomfield, S.; Martin, A.M.; et al. Disparities in prostate cancer screening, diagnoses, management, and outcomes between Indigenous and non-Indigenous men in a universal health care system. Cancer 2023, 129, 2864–2870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Agency for Research on Cancer, World Health Organisation, Global Initiative for Cancer Registry Development: The Value of Cancer Data. Available online: https://gicr.iarc.fr/about-the-gicr/the-value-of-cancer-data/ (accessed on 8 May 2025).

| Incidence (Excluding Quebec) | Mortality | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age Group | Trend Period | Annual Percent Change (95% Confidence Limits) | p-Value | Trend Period | Annual Percent Change (95% Confidence Limits) | p-Value |

| 50+ | 1984–1993 | 5.8 (4.1, 9.1) | <0.001 | 1984–1994 | 1.3 (0.7, 2.0) | <0.001 |

| 1993–2009 | −0.2 (−0.8, 0.5) | 0.554 | 1994–2012 | −2.8 (−3.2, −2.6) | <0.001 | |

| 2009–2014 | −7.1 (−8.5, −4.4) | 0.001 | 2012–2023 | −1.4 (−1.8, −0.6) | 0.010 | |

| 2014–2022 | 0.9 (−0.5, 3.3) | 0.154 | ||||

| 50–74 | 1984–1993 | 9.0 (6.9, 13.8) | 0.001 | 1984–1988 | 3.8 (1.0, 5.7) | 0.001 |

| 1993–2007 | 1.8 (0.7, 2.9) | 0.006 | 1988–1994 | −0.8 (−4.4, 0.1) | 0.077 | |

| 2007–2014 | −5.9 (−8.8, −4.0) | 0.005 | 1994–2010 | −4.3 (−5.1, −1.3) | 0.022 | |

| 2014–2022 | 0.2 (−1.6, 3.2) | 0.687 | 2010–2023 | −1.0 (−1.6, −0.3) | 0.023 | |

| 75+ | 1984–1992 | 3.2 (1.6, 5.6) | <0.001 | 1984–1995 | 1.4 (0.9, 2.0) | <0.001 |

| 1992–2015 | −3.2 (−3.7, −3.0) | <0.001 | 1995–2012 | −2.5 (−3.1, −2.3) | 0.001 | |

| 2015–2022 | 1.3 (−0.4, 3.6) | 0.115 | 2012–2023 | −1.6 (−1.9, −0.7) | 0.006 | |

| Incidence (Excluding Quebec) | Mortality | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age Group | Trend Period | Annual Percent Change (95% Confidence Limits) | p-Value | Trend Period | Annual Percent Change (95% Confidence Limits) | p-Value |

| 50–54 | 1984–2001 | 11.3 (9.9, 16.5) | <0.001 | 1984–2023 | −1.6 (−2.3, −0.8) | 0.001 |

| 2001–2007 | 3.4 (−2.4, 8.8) | 0.179 | ||||

| 2007–2022 | −4.2 (−5.8, −3.3) | 0.001 | ||||

| 55–59 | 1984–2001 | 8.9 (7.8, 10.8) | 0.001 | 1984–2002 | −2.0 (−2.9, 1.0) | 0.086 |

| 2001–2009 | 1.0 (−1.1, 4.1) | 0.285 | 2002–2007 | −8.3 (−11.0, −3.2) | 0.028 | |

| 2009–2014 | −8.0 (−9.8, −5.0) | 0.007 | 2007–2023 | 0.1 (−1.2, 3.1) | 0.669 | |

| 2014–2022 | −0.9 (−2.5, 2.1) | 0.555 | ||||

| 60–64 | 1984–1993 | 11.0 (8.5, 16.6) | 0.001 | 1984–1988 | 5.4 (0.0, 9.1) | 0.051 |

| 1993–2007 | 2.9 (1.7, 4.1) | 0.004 | 1988–2011 | −3.6 (−4.7, −3.3) | <0.001 | |

| 2007–2015 | −6.1 (−9.2, −4.5) | 0.006 | 2011–2023 | −0.5 (−1.6, 1.5) | 0.488 | |

| 2015–2022 | 0.1 (−2.1, 3.0) | 0.818 | ||||

| 65–69 | 1984–1993 | 9.2 (7.1, 13.8) | <0.001 | 1984–1993 | 2.2 (0.7, 4.4) | 0.004 |

| 1993–2007 | 1.6 (0.5, 2.7) | 0.008 | 1993–2011 | −4.4 (−5.7, −3.9) | <0.001 | |

| 2007–2014 | −6.0 (−8.9, −4.1) | 0.001 | 2011–2023 | −0.6 (−1.8, 1.3) | 0.359 | |

| 2014–2022 | 0.7 (−0.9, 3.6) | 0.290 | ||||

| 70–74 | 1984–1993 | 7.4 (5.6, 10.8) | 0.002 | 1984–1988 | 4.9 (1.4, 7.9) | 0.010 |

| 1993–2009 | −1.0 (−1.7, 0.0) | 0.055 | 1988–2000 | −2.4 (−3.2, −1.6) | <0.001 | |

| 2009–2014 | −6.5 (−8.3, −3.3) | 0.002 | 2000–2006 | −6.7 (−8.4, −4.7) | 0.009 | |

| 2014–2022 | 1.6 (−0.2, 4.9) | 0.062 | 2006–2023 | −1.6 (−2.0, −0.8) | 0.008 | |

| 75–79 | 1984–1992 | 5.9 (3.4, 9.8) | <0.001 | 1984–1995 | 0.5 (−0.4, 1.6) | 0.274 |

| 1992–2016 | −2.7 (−3.5, −2.4) | <0.001 | 1995–2013 | −4.1 (−5.0, −3.7) | <0.001 | |

| 2016–2022 | 3.2 (−0.3, 6.0) | 0.066 | 2013–2023 | −1.3 (−2.4, 1.0) | 0.126 | |

| 80–84 | 1984–1992 | 3.9 (2.6, 5.9) | <0.001 | 1984–1992 | 2.1 (0.8, 3.9) | 0.001 |

| 1992–1997 | −5.8 (−6.8, −3.5) | 0.002 | 1992–2023 | −2.6 (−2.8, −2.5 | <0.001 | |

| 1997–2016 | −3.0 (−3.5, −2.1) | <0.001 | ||||

| 2016–2022 | 2.0 (0.1, 4.0) | 0.041 | ||||

| 85+ | 1984–1992 | 0.5 (−0.9, 2.9) | 0.442 | 1984–1995 | 1.7 (0.9, 2.9) | <0.001 |

| 1992–2015 | −3.7 (−4.3, −3.5) | <0.001 | 1995–2023 | −1.5 (−1.7, −1.4) | <0.001 | |

| 2015–2022 | −0.8 (−2.4, 1.1) | 0.370 | ||||

| Stage I to III | Stage IV | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age Group | Annual Percent Change (95% Confidence Limits) | p-Value | Annual Percent Change (95% Confidence Limits) | p-Value |

| 50–74 | −4.9 (−11.2, 1.7) | 0.137 | 3.7 (1.0, 6.9) | 0.010 |

| 75+ | −2.4 (−6.7, 2.0) | 0.252 | 3.1 (1.6, 5.0) | <0.001 |

| 50–59 | −5.8 (−11.1, −0.6) | 0.032 | 2.6 (0.3, 5.2) | 0.022 |

| 60–69 | −4.8 (−10.2, 0.9) | 0.093 | 4.1 (3.1, 5.3) | <0.001 |

| 70–79 | −3.3 (−8.8, 2.5) | 0.239 | 3.9 (1.6, 6.7) | <0.001 |

| 70–74 | −3.7 (−10.4, 3.5) | 0.275 | 4.5 (−0.6, 10.9) | 0.079 |

| 75–79 | −2.8 (−8.0, 2.6) | 0.267 | 3.8 (1.2, 6.7) | 0.006 |

| 80+ | −2.3 (−5.4, 1.0) | 0.174 | 3.0 (1.5, 4.6) | <0.001 |

| 80–84 | −1.7 (−4.8, 1.7) | 0.279 | 3.4 (2.3, 4.6) | <0.001 |

| 85+ | −2.7 (−5.1, −0.2) | 0.033 | 2.2 (−0.2, 5.0) | 0.068 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wilkinson, A.N.; Ellison, L.F.; Zhang, S.X.; Ong, M.; Morgan, S.C.; Goldenberg, S.L.; Breau, R.H.; Morash, C. Canadian Prostate Cancer Trends in the Context of PSA Screening Guideline Changes. Curr. Oncol. 2025, 32, 669. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32120669

Wilkinson AN, Ellison LF, Zhang SX, Ong M, Morgan SC, Goldenberg SL, Breau RH, Morash C. Canadian Prostate Cancer Trends in the Context of PSA Screening Guideline Changes. Current Oncology. 2025; 32(12):669. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32120669

Chicago/Turabian StyleWilkinson, Anna N., Larry F. Ellison, Shary X. Zhang, Michael Ong, Scott C. Morgan, S. Larry Goldenberg, Rodney H. Breau, and Christopher Morash. 2025. "Canadian Prostate Cancer Trends in the Context of PSA Screening Guideline Changes" Current Oncology 32, no. 12: 669. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32120669

APA StyleWilkinson, A. N., Ellison, L. F., Zhang, S. X., Ong, M., Morgan, S. C., Goldenberg, S. L., Breau, R. H., & Morash, C. (2025). Canadian Prostate Cancer Trends in the Context of PSA Screening Guideline Changes. Current Oncology, 32(12), 669. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32120669