Effect of Contamination by Phosphate Mining Effluent on Biocrust Microbial Community Structure and Cyanobacterial Diversity in a Hot Dry Desert

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

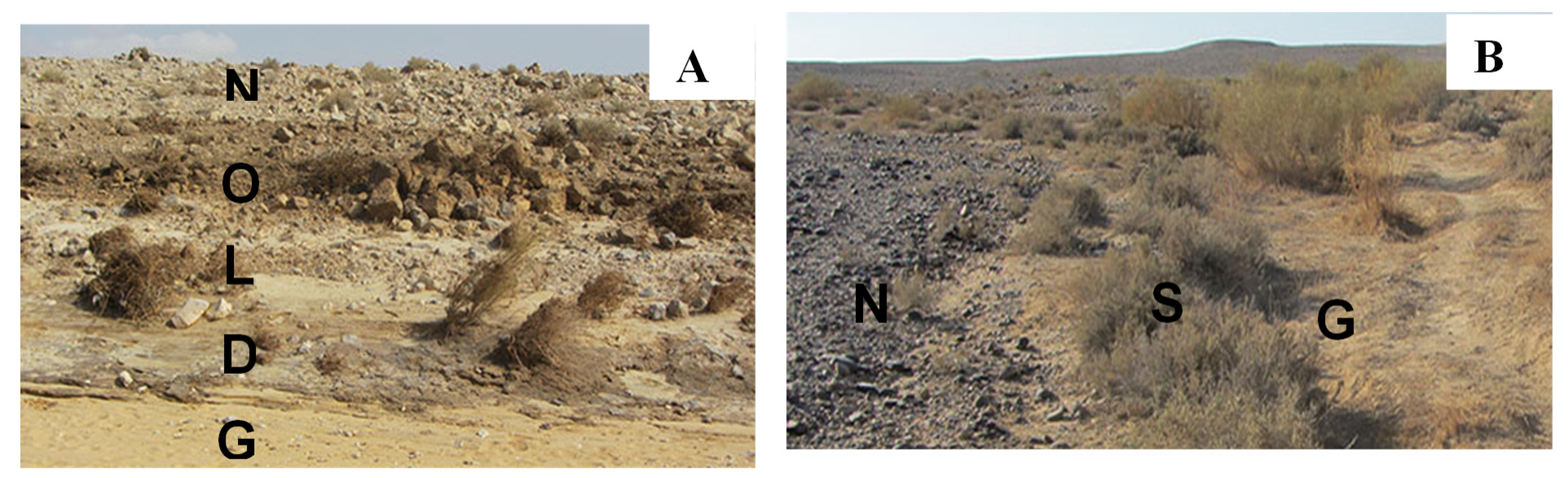

2.1. Site Description and Sample Collection

2.2. Chemical Characterization of Biocrust Samples

2.3. DNA Extraction, qPCR Assays and High-Throughput Sequencing

3. Results

3.1. Biocrust Chemical Characteristics

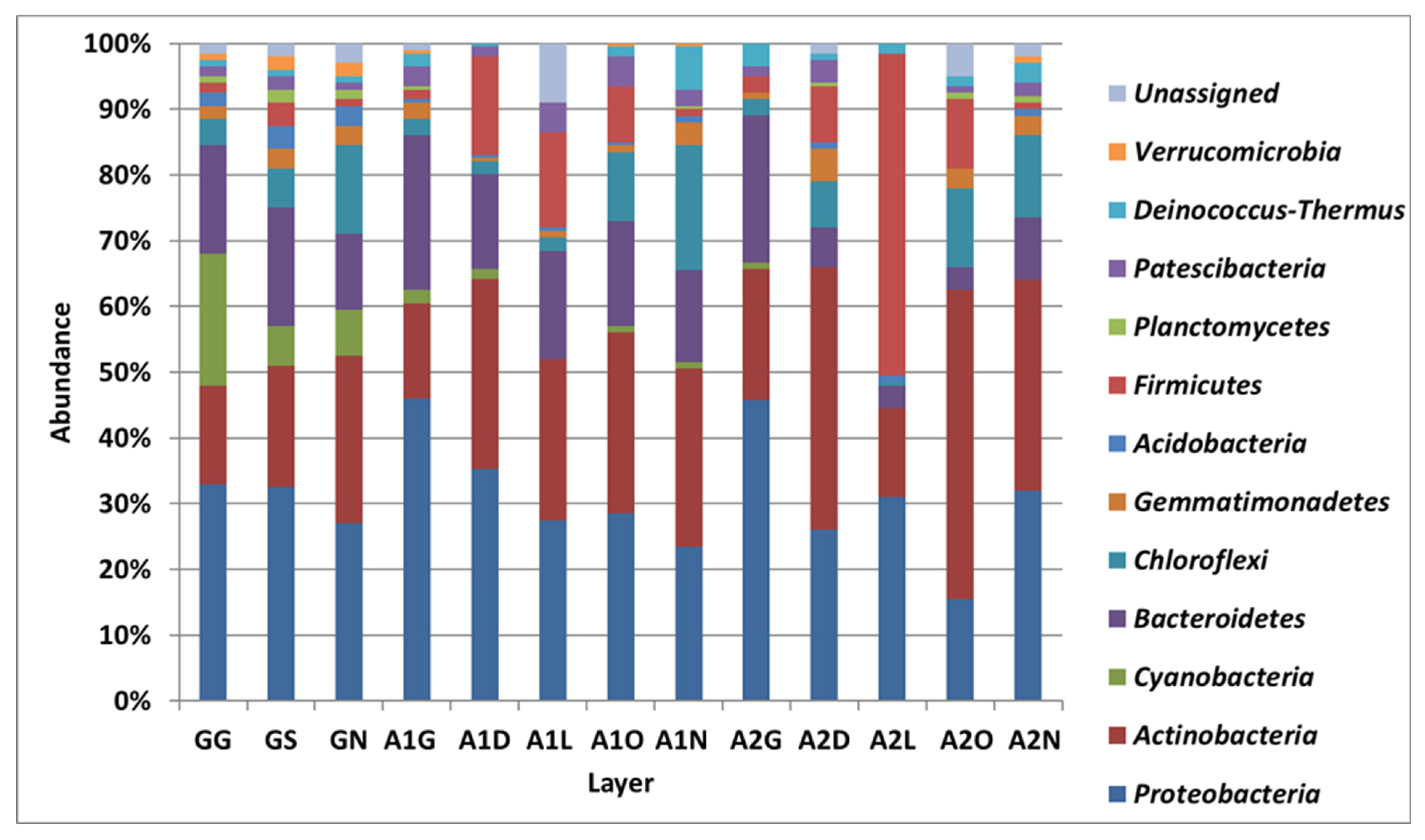

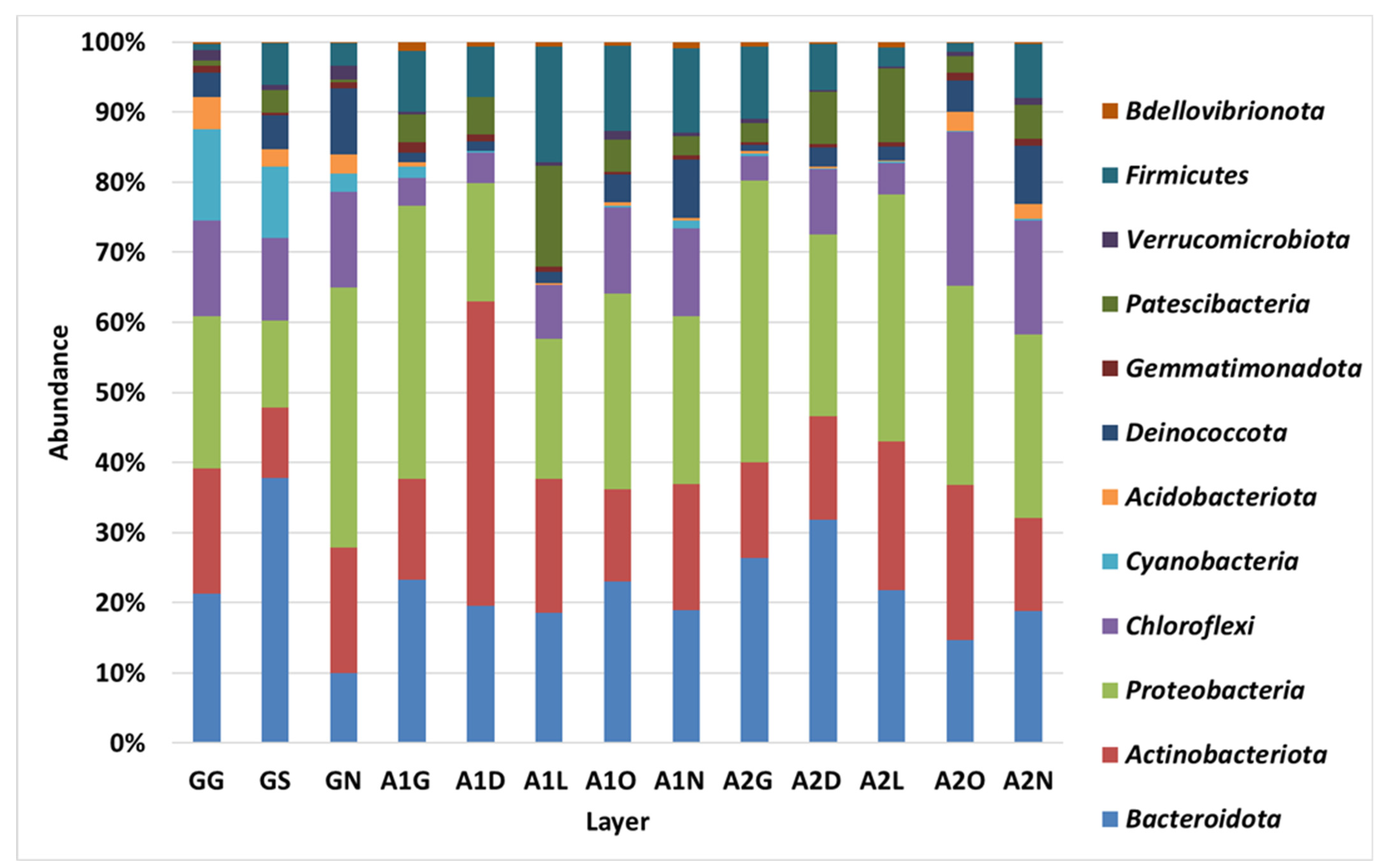

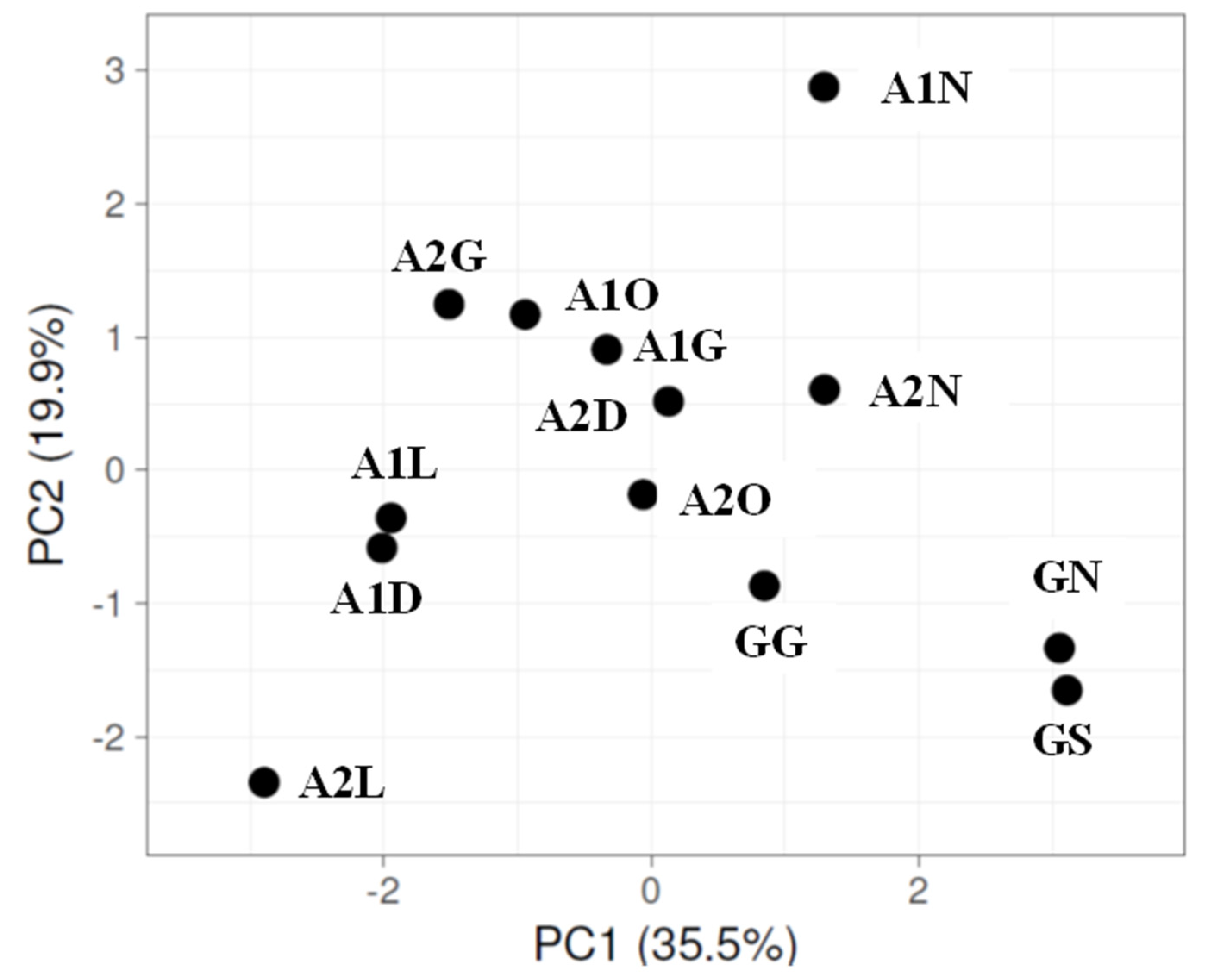

3.2. Bacterial Diversity in the Biocrust Strips: Phylum Level

3.3. Bacterial Diversity in the Biocrust Strip: Genus Level

3.4. Cyanobacteria and nifH Abundance

4. Discussion

4.1. Bacterial Diversity: Phylum Level

4.2. Bacterial Diversity: Genus Level

4.3. Cyanobacteria and the Potential for Nitrogen Fixation

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schlesinger, W.H.; Reynolds, J.F.; Cunningham, G.L.; Huenneke, L.F.; Jarrell, W.M.; Virginia, R.A.; Whitford, W.G. Biological feedbacks in global desertification. Science 1990, 247, 1043–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Austin, A.; Yahdjian, L.; Stark, J.M.; Belnap, J.; Porporato, A.; Norton, U.; Damián, A.; Ravetta, D.A.; Schaeffer, S.M. Water pulses and biogeochemical cycles in arid and semiarid ecosystems. Oecologia 2004, 141, 221–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maestre, F.T.; Salguero-Gomez, R.; Quero, J.L. It is getting hotter in here: Determining and projecting the impacts of global environmental change on drylands. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 2012, 367, 3062–3075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowker, M.A.; Reed, S.C.; Maestre, F.T.; Eldridge, D.J. Biocrusts: The living skin of the earth. Plant Soil 2018, 429, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, B.; Belnap, J.; Büdel, B.; Antoninka, A.J.; Barger, N.N.; Chaudhary, V.B.; Darrouzet-Nardi, A.; Eldridge, D.J.; Faist, A.M.; Ferrenberg, S.; et al. What is a biocrust? A refined, contemporary definition for a broadening research community. Biol. Rev. 2022, 97, 1768–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, N.E. Structure and function of microphytic soil crusts in wildland ecosystems of arid to semi-arid regions. Adv. Ecol. Res. 1990, 20, 179–223. [Google Scholar]

- Belnap, J.; Büdel, B.; Lange, O.L. Biological soil crusts: Characteristics and distribution. In Biological Soil Crusts: Structure, Function, and Management. Ecological Studies (Analysis and Synthesis); Belnap, J., Lange, O.L., Eds.; Springer Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2001; pp. 3–30. [Google Scholar]

- Belnap, J.; Welter, J.R.; Grimm, N.B.; Barger, N.; Ludwig, J.A. Linkages between microbial and hydrologic processes in arid and semiarid watersheds. Ecology 2005, 86, 298–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Pichel, F. Desert environments: Biological soil crusts. In Encyclopedia of Environmental Microbiology; Bitton, G., Ed.; John Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 1019–1023. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Caballero, E.; Canton, Y.; Chamizo, S.; Ashraf Afana, A.; Solé-Benet, A. Effects of biological soil crusts on surface roughness and implications for runoff and erosion. Geomorphology 2012, 145–146, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaady, E.; Groffman, P.; Shachak, M. Nitrogen fixation in macro and microphytic patches in the Negev desert. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1998, 30, 449–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, R.; Lange, O. Biological soil crusts and ecosystem nitrogen and carbon dynamics. In Biological Soil Crusts: Structure, Function, and Management; Benlap, J., Lange, O.L., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2003; pp. 263–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.L.; Neuer, S.; Garcia-Pichel, F. Export of nitrogenous compounds due to incomplete cycling within biological soil crusts of arid lands. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 9, 680–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yair, A.; Veste, M.; Almog, R.; Breckle, S.W. Sensitivity of a sandy area to climate change along a rainfall gradient at a desert fringe. In Arid Dune Ecosystems—The Nizzana Sands in the Negev Desert; Ecological Studies Series; Breckle, S.W., Yair, A., Veste, M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; Volume 200, pp. 425–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejidat, A.; Potrafka, R.M.; Zaady, E. Successional biocrust stages on dead shrub soil mounds after severe drought: Effect of micro-geomorphology on microbial community structure and ecosystem recovery. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2016, 103, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belnap, J.; Lange, O.L. Biological Soil Crusts: Structure, Function, and Management; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2001; 503p. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, F.P. Mining industry and sustainable development: Time for change. Food Energy Secur. 2017, 6, 61–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virah-Sawmy, M.; Ebeling, J.; Taplin, R. Mining and biodiversity offsets: A transparent and science-based approach to measure “no-net-loss”. J. Environ. Manag. 2014, 143, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abed, R.M.M.; Al-Kindi, S. Diversity of bacterial communities along a petroleum contamination gradient in desert soils. Environ. Microbiol. 2015, 69, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abed, R.M.M.; Al-Kindi, S. Effect of disturbance by oil pollution on the diversity and activity of bacterial communities in biological soil crusts from the Sultanate of Oman. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2017, 110, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y. Environmental problems in the mining of metal minerals. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 384, 012195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luckeneder, S.; Giljum, S.; Schaffartzik, A.; Maus, V.; Tost, M. Surge in global metal mining threatens vulnerable ecosystems. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2021, 69, 102303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsin, M.; Zhu, Q.; Naseem, S.; Sarfraz, M.; Ivascu, L. Mining industry impact on environmental sustainability, economic growth, social interaction, and public health: An application of semi-quantitative mathematical approach. Processes 2021, 9, 972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejidat, A.; Meshulam, M.; Diaz-Reck, D.; Ronen, Z. Emergence of hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria in crude oil-contaminated soil in a hyperarid ecosystem: Effect of phosphate addition and augmentation with nitrogen-fixing cyanobacteria on oil bioremediation. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2023, 178, 105556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerem, T.; Nejidat, A.; Zaady, E. Monitoring dynamics of biocrust rehabilitation in acid-saturated desert soils. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2024, 196, 715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Even-Danan, R.; Shalom, H.; Blitman, R.; Nassar, H.; David, R.; Fadlon, L.; Miller, A. Policy Document for the Treatment of Current Waste from Phosphoric Acid Production Plants; Israel Ministry of Environmental Protection: Jerusalem, Israel, 2014. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Tzoar, A. Description of the Nahal Ashalim c ase. In Literature Survey on the Nahal Ashalim Pollution: Risk Assessment and Possible Treatment Methods; Shapira, A., Chen, R., Eds.; Hamaarag, Tel Aviv University: Tel Aviv, Israel, 2018; pp. 6–9. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- APHA. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater, 17th ed.; American Public Health Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Ferree, M.A.; Shannon, R.D. Evaluation of a second derivative UV/visible spectroscopy technique for nitrate and total nitrogen analysis of wastewater samples. Water Res. 2001, 35, 327–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mevarech, M.; Rice, D.; Haselkorn, R. Nucleotide sequence of a cyanobacterial nifH gene coding for nitrogenase reductase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1980, 77, 6476–6480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeager, C.M.; Kornosky, J.L.; Housman, D.C.; Grote, E.E.; Belnap, J.; Kuske, C.R. Diazotrophic community structure and function in two successional stages of biological soil crusts from the Colorado Plateau and Chihuahuan Desert. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004, 70, 973–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nubel, U.; Garcia-Pichel, F.; Muyzer, G. PCR primers to amplify rRNA genes from cyanobacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1997, 63, 3327–3332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muyzer, G.; De Waal, E.C.; Uitterlinden, A.G. Profiling of complex microbial populations by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis analysis of polymerase chain reaction-amplified genes coding for 16S rRNA. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1993, 59, 695–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klindworth, A.; Pruesse, E.; Schweer, T.; Peplies, J.; Quast, C.; Horn, M.; Glöckner, F.O. Evaluation of general 16S ribosomal RNA gene PCR primers for classical and next-generation sequencing-based diversity studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 41, e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ionescu, D.; Overholt, W.; Lynch, M.D.J.; Neufeld, J.D.; Naqib, A.; Green, S.J. Microbial community analysis using high-throughput amplicon sequencing. In Manual of Environmental Microbiology, 4th ed.; ASM Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; pp. 2–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolyen, E.; Rideout, J.R.; Dillon, M.R.; Bokulich, N.A.; Abnet, C.C.; Al-Ghalith, G.A.; Alexander, H.; Alm, E.J.; Arumugam, M.; Asnicar, F.; et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 852–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, B.J.; McMurdie, P.J.; Rosen, M.J.; Han, A.W.; Johnson, J.A.; Holmes, S.P. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 2016, 13, 581–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokulich, N.A.; Kaehler, B.D.; Rideout, J.R.; Dillon, M.; Bolyen, E.; Knight, R.; Huttley, G.A.; Caporaso, J.G. Optimizing taxonomic classification of marker-gene amplicon sequences with QIIME 2’s q2-feature-classifier plugin. Microbiome 2018, 6, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

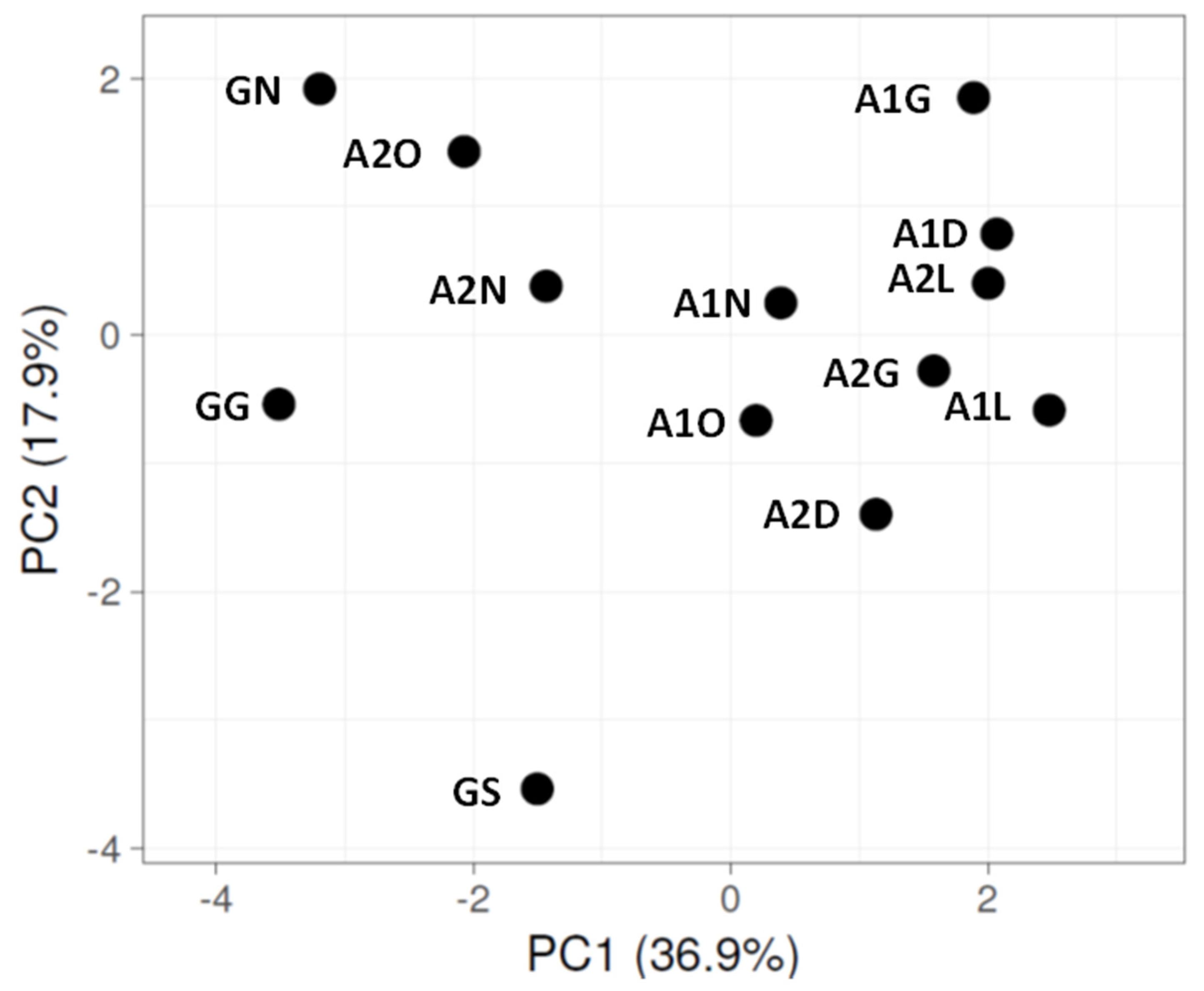

- Tauno, M.; Jaak, V. Clustvis: A web tool for visualizing clustering of multivariate data using Principal Component Analysis and heatmap. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, W566–W570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Shi, Y.; Cui, X.; Yue, P.; Li, K.; Liu, X.; Tripathi, B.M.; Chu, H. Salinity is a key determinant for soil microbial communities in a desert ecosystem. mSystems 2019, 4, e00225-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banda, J.F.; Zhang, Q.; Ma, L.; Pei, L.; Du, Z.; Hao, C.; Dong, H. The effects of salinity and pH on microbial community diversity and distribution pattern in the brines of soda lakes in Badain Jaran Desert, China. Geomicrobiol. J. 2020, 37, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banda, J.F.; Zhang, Q.; Ma, L.; Pei, L.; Du, Z.; Hao, C.; Dong, H. Both pH and salinity shape the microbial communities of the lakes in Badain Jaran Desert, NW China. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 791, 148108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, J.; Wyness, A.J.; Claire, M.W.; Zerkle, A.L. Spatial variability of microbial communities and salt distributions across a latitudinal aridity gradient in the Atacama Desert. Microb. Ecol. 2021, 82, 442–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, M.L.; Pérez, A.; Garcia-Pichel, F. The prokaryotic diversity of biological soil crusts in the Sonoran Desert (Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, AZ). FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2005, 54, 233–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barka, E.A.; Vatsa, P.; Sanchez, L.; Gaveau-Vaillant, N.; Jacquard, C.; Klenk, H.; Clément, C.; Ouhdouch, Y.; van Wezel, G.P. Taxonomy, physiology, and natural products of Actinobacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2015, 80, 1–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippidou, S.; Wunderlin, T.; Junier, T.; Nicole, J.; Cristina, D.; Veronica, M. Combination of extreme environmental conditions favor the prevalence of endospore-forming Firmicutes. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulze-Makuch, D.; Wagner, D.; Kounaves, S.P.; Zamorano, P. Transitory microbial habitat in the hyperarid Atacama Desert. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 2670–2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fierer, N.; Lauber, C.L.; Ramirez, K.S.; Zaneveld, J.; Bradford, M.A.; Knight, R. Comparative metagenomic, phylogenetic and physiological analyses of soil microbial communities across nitrogen gradients. ISME J. 2012, 6, 1007–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrshad, M.; Salcherm, M.M.; Okazaki, Y.; Nakano, S.; Šimek, K.; Andrei, A.S.; Ghai, R. Hidden in plain sight—Highly abundant and diverse planktonic freshwater Chloroflexi. Microbiome 2018, 6, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speirs, L.B.M.; Rice, D.T.F.; Petrovski, S.; Seviour, R.J. The phylogeny, biodiversity, and ecology of the Chloroflexi in activated sludge. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, J.S.; Campbell, J.H.; Grizzle, H.; Acosta-Martìnez, V.; Zak, J.C. Soil microbial community response to drought and precipitation variability in the Chihuahuan Desert. Microb. Ecol. 2009, 57, 248–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, D.S.; Lee, H.G.; Im, W.T.; Liu, Q.M.; Lee, S.T. Segetibacter koreensis gen. nov., sp. nov., a novel member of the phylum Bacteroidetes, isolated from the soil of a ginseng field in South Korea. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2007, 57, 1828–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulichevskaya, I.S.; Suzina, N.E.; Liesack, W.; Dedysh, S.N. Bryobacter aggregatus gen. nov., sp. nov., a peat-inhabiting, aerobic chemo-organotroph from subdivision 3 of the Acidobacteria. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2010, 60, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Pichel, F.; Wojciechowski, M.F. The evolution of a capacity to build supra-cellular ropes enabled filamentous cyanobacteria to colonize highly erodible substrates. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e7801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazor, G.; Kidron, G.J.; Vonshak, A.; Abeliovich, A. The role of cyanobacterial exopolysaccharides in structuring desert microbial crusts. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 1996, 21, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dal-Ferro, L.S.; Schenider, A.; Missiaggia, D.G.; Silva, L.J.; Maciel-Silva, A.S.; Figueredo, C.C. Organizing a global list of cyanobacteria and algae from soil biocrusts evidenced great geographic and taxonomic gaps. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2024, 100, fiae086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaady, E.; Ben-David, E.A.; Sher, Y.; Tzirkin, R.; Nejidat, A. Inferring biological soil crust successional stage using combined PLFA, DGGE, physical and biophysiological analyses. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2010, 42, 842–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panigada, C.; Tagliabue, G.; Zaady, E.; Rozenstein, O.; Garzonio, R.; Di Mauro, B.; De Amicis, M.; Colombo, R.; Cogliati, S.; Miglietta, F.; et al. A new approach for biocrust and vegetation monitoring in drylands using multi-temporal Sentinel-2 images. Prog. Phys. Geogr. 2019, 43, 496–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagemann, M.; Henneberg, M.; Felde, V.J.M.N.; Drahorad, S.L.; Berkowicz, S.M.; Felix-Henningsen, P.; Kaplan, A. Cyanobacterial diversity in biological soil crusts along a precipitation gradient, Northwest Negev Desert, Israel. Microb. Ecol. 2015, 70, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mühlsteinová, R.; Johansen, J.R.; Pietrasiak, N.; Martin, P.M.; Osorio-Santos, K.; Warren, S.D. Polyphasic characterization of Trichocoleus desertorum sp. nov. (Pseudanabaenales, Cyanobacteria) from desert soils and phylogenetic placement of the genus Trichocoleus. Phytotaxa 2014, 163, 241–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeager, C.M.; Kornosky, J.L.; Morgan, R.E.; Cain, E.C.; Garcia-Pichel, F.; Housman, D.C.; Belnap, J.; Kuske, C.R. Three distinct clades of cultured heterocystous cyanobacteria constitute the dominant N2-fixing members of biological soil crusts of the Colorado Plateau. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2007, 60, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kidron, G.J.; Posmanik, R.; Brunner, T.; Nejidat, A. Spatial abundance of microbial nitrogen-transforming genes and inorganic nitrogen in biocrusts along a transect of an arid sand dune in the Negev Desert. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2015, 83, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barger, N.; Weber, B.; Garcia-Pichel, F.; Zaady, E.; Belnap, J. Patterns and controls on nitrogen cycling of biological soil crusts. In Biological Soil Crusts: An Organizing Principle in Drylands; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 257–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, S.; Thomas, A.D.; Rakes, J.B.; Garcia-Pichel, F.; Wu, L.; Hu, C. Cyanobacterial community composition and their functional shifts associated with biocrust succession in the Gurbantunggut Desert. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2021, 13, 884–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaady, E.; Offer, Z.Y.; Shachak, M. The content and contributions of deposited aeolian organic matter in a dry land ecosystem of the Negev Desert, Israel. Atmos. Environ. 2001, 35, 769–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenhoudt, O.; Vanderleyden, J. Azospirillum, a free-living nitrogen-fixing bacterium closely associated with grasses: Genetic, biochemical and ecological aspects. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2000, 24, 487–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogul, R.; Vaishampayan, P.; Bashir, M.; McKay, C.P.; Schubert, K.; Bornaccorsi, R.; Gomez, E.; Tharayil, S.; Payton, G.; Capra, J.; et al. Microbial community and biochemical dynamics of biological soil crusts across a gradient of surface coverage in the Central Mojave Desert. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabay, T.; Rotem, G.; Gillor, O.; Ziv, Y. Understanding changes in biocrust communities following phosphate mining in the Negev Desert. Environ. Res. 2022, 207, 112200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| November 2018 Samplings | July 2022 Samplings | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH | EC | TAN | NO3−N | pH | EC | TAN | NO3−N | |

| Site 1—Ashalim 1 | ||||||||

| G | 6.8 ± 0.0 b * | 2014 ± 999 ab | 6.5 ± 1.5 b | 3.0 ± 2.0 b | 7.2 ± 0.1 b | 857 ± 111 a | 5.7 ± 8.1 ab | 14.2 ± 4.9 a |

| D | 7.0 ± 0.1 a | 1597 ± 814 b | 14.8 ± 9.4 ab | 66.8 ± 76.4 ab | 6.1 ± 0.2 c | 443 ± 299 bc | 14.2 ± 7.3 a | 4.0 ± 2.9 b |

| L | 7.0 ± 0.1 a | 856 ± 296 c | 16.1 ± 7.5 a | 23.3 ± 31.0 ab | 7.9 ± 0.2 ab | 239 ± 151 c | 13.7 ± 5.6 a | 3.0 ± 4.7 b |

| O | 6.7 ± 0.0 c | 3322 ± 481 a | 7.0 ± 4.6 ab | 12.0 ± 7.5 ab | 7.9 ± 0.1 ab | 479 ± 245 bc | 1.2 ± 1.8 b | 9.7 ± 7.0 ab |

| N | 7.1 ± 0.1 a | 1412 ± 539 bc | 6.6 ± 2.2 b | 55.5 ± 37.3 a | 8.3 ± 0.3 a | 415 ± 365 bc | 6.7 ± 5.7 b | 15.0 ± 20.2 ab |

| Site 2—Ashalim 2 | ||||||||

| G | 7.1 ± 0.1 a | 1400 ± 606 b | 8.2 ± 2.1 ab | 2.5 ± 1.7 c | 7.8 ± 0.1 b | 531 ± 125 a | 2.7 ± 4.8 abc | 15.5 ± 5.4 a |

| D | 6.8 ± 0.0 b | 2457 ± 73 ab | 8.8 ± 2.6 ab | 28.7 ± 44.4 ab | 8.1 ± 0.3 ab | 319 ± 150 ab | 17.0 ± 11.5 a | 6.7 ± 6.4 ab |

| L | 6.6 ± 0.1 c | 2667 ± 176 ab | 12.6 ± 3.0 a | 9.9 ± 8.8 abc | 8.0 ± 0.5 ab | 395 ± 386 ab | 8.5 ± 5.1 ab | 7.0 ± 2.3 b |

| O | 6.9 ± 0.2 b | 3237 ± 849 a | 2.9 ± 2.5 c | 22.8 ± 9.3 ab | 8.4 ± 0.0 a | 142 ± 28 b | 6.5 ± 3.6 ab | 16.2 ± 9.6 ab |

| N | 7.1 ± 0.1 a | 668 ± 166 c | 5.0 ± 2.2 bc | 20.6 ± 12.1 ab | 8.2 ± 0.2 ab | 334 ± 151 ab | 0.25 ± 0.5 c | 33.0 ± 32.3 abc |

| Control—Gmalim | ||||||||

| G | 6.4± 0.0 c | 112 ± 28 c | 0.1 ± 0.0 a | 2.4 ± 1.4 b | 8.3 ± 0.2 b | 262 ± 210 a | 1.75 ± 0.95 b | 4.3 ± 1.5 b |

| S | 8.75 ± 0.2 a | 468 ± 276 b | 1.5 ± 1.9 a | 33.8 ± 23.8 a | 8.9 ± 0.2 a | 209 ± 79 a | 1.5 ± 2.6 b | 31.7 ± 12.2 a |

| N | 8.15 ± 0.3 b | 1581 ± 1080 a | 0.6 ± 1.2 a | 27.2 ± 11.3 a | 8.6 ± 0.4 ab | 267 ± 191 a | 8.75 ± 3.8 a | 13.0 ± 10.4 ab |

| Control—Gmalim | Site 1-Ashalim 1 | Site 2-Ashalim 2 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Stream Bed | Shrubs | Stream Banks | Stream Bed | Dark Soil | Bright Soil | OM Foam | Stream Banks | Stream Bed | Dark Soil | Bright Soil | OM Foam | Stream Banks |

| Relative abundance of Cyanobacteria phylum | |||||||||||||

| 2018 | 20.0 | 6.0 | 7.0 | 2.0 | 1.5 | 0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2022 | 13.0 | 10.1 | 2.5 | 1.6 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 1.1 | 0.4 | 0.17 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.3 |

| Relative abundance of Cyanobacteria genera (2022) | |||||||||||||

| Leptolyngbya | 54.64 | 39.97 | 69.37 | 93.62 | 67.9 | 88.5 | 94.23 | 94.21 | 91.85 | 95.29 | 84.37 | 64.32 | 91.47 |

| Tychonema_CCAP_1459-11B | 11.27 | 18.09 | 27.02 | 2.44 | 23.93 | 0.44 | 0.76 | 0.70 | 0.92 | 2.11 | 0.81 | 15.54 | 0.07 |

| Trichocoleus_SAG_26.92 | 1.25 | 1.83 | 0.54 | 0.64 | 3.59 | 0.00 | 0.63 | 2.13 | 0.28 | 0.09 | 1.68 | 2.69 | 3.10 |

| Nostoc | 0.21 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Scytonema | 1.03 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.54 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Symplocastrum_ | 1.85 | 0.06 | 0.43 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.09 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| CENA518 | 8.87 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Calothrix_PCC-6303 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.49 | 0.00 |

| Sericytochromatia | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.61 | 0.05 |

| Microcoleus | 0.16 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Nodosilinea_ | 14.11 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.15 |

| Crinalium | 2.64 | 0.33 | 1.16 | 0.29 | 0.00 | 5.48 | 0.53 | 0.61 | 1.15 | 0.00 | 1.95 | 8.32 | 0.39 |

| LWQ8 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 4.08 | 0.98 | 0.12 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 1.68 | 2.02 | 0.39 |

| Aliterella | 0.15 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.28 | 0.43 | 0.16 | 0.28 | 0.07 | 0.75 | 1.16 | 0.22 |

| Pleurocapsa | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.28 | 0.25 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.12 | 1.14 |

| Loriellopsis | 0.22 | 0.07 | 0.27 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.35 | 0.61 | 0.48 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 1.53 | 0.19 |

| Vampirovibrio | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.67 | 0.09 | 0.12 | 0.04 | 0.23 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.10 |

| Uncultured | 3.37 | 39.39 | 1.02 | 2.66 | 0.00 | 3.33 | 2.14 | 1.29 | 4.87 | 1.15 | 8.03 | 1.52 | 2.28 |

| Layer | nifH 2018 | Cyanobacteria 2018 | nifH 2022 | Cyanobacteria 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ashalim 1 | ||||

| G | 31,300 ± 3535 | 2.0 | 5500 ± 2380 | 1.6 |

| D | 27,700 ± 39,173 | 1.5 | 5750 ± 2500 | 0.2 |

| L | 30,429 ± 43,033 | 0 | 7250 ± 3095 | 0.1 |

| O | - | 1.0 | 4252 ± 3496 | 0.2 |

| N | 22,228 ± 31,436 | 1.0 | 106,000 ± 19,602 | 1.1 |

| Ashalim 2 | ||||

| G | 16,630 ± 23,518 | 1.0 | 13,250 ± 17,876 | 0.4 |

| D | 41,675 ± 10,720 | 0 | 5000 ± 1825 | 0.17 |

| L | 45,712 ± 12,444 | 0 | 3100 ± 3450 | 0.2 |

| O | 17,490 ± 24,734 | 0 | 1375 ± 750 | 0.1 |

| N | 29,296 ± 3247 | 0 | 14,000 ± 10,708 | 0.3 |

| Gmalim | ||||

| G | 157,462 ± 15,084 | 20.0 | 518,000 ± 98,813 | 13.0 |

| S | 28,100 ± 19,657 | 6.0 | 1575 ± 1650 | 10.1 |

| N | 7900 ± 11,172 | 7.0 | 6500 ± 3696 | 2.5 |

| November 2018 | July 2022 | |

|---|---|---|

| Dominant genera in the Ashalim stream | Blastococcus, Geodermatophilus, Modestobacter, Arthrobacter, Kocuria, Pseudoarthrobacter, Marmoricola, Rubrobacter, Solirubrobacer, Flaviaesturariibacter, Rhodocytophaga, Adhaeribacter, Hymenobacter, Pontibactor, Truepera, Bacillus, Paenibacillus, Planomicrobiom, Pulluanibacillus, Skermanella, Microvirga, Rubellimicrobium, Ellin6055, Sphingomonas, Massilia, Noviherbaspirillum. | Bryobacter, Blastococcus, Arthrobacter, Kocuria, Pseudoarthrobacter, Rubrobacter, Flaviaesturariibacter, Rhodocytophaga, Adhaeribacter, Nitrobacter, Pontibactor, AKIW781, AKYG1722, JG30-KF-CM45, Truepera, Bacillus, Planococcus, LWQ8, TM7a, Saccharimonadales, Skermanella, Microvirga, Devosia, Rubellimicrobium, Sphingomonas, Nitrosospira. |

| Dominant genera in the control stream | Bryobacter, Blastococcus, Geodermatophilus, Arthrobacter, Pseudoarthrobacter, Rubrobacter, Flaviaesturariibacter, Segetibacter, Rhodocytophaga, Adhaeribacter, Hymenobacter, Pontibactor, Truepera, Planomicrobiom, Skermanella, Microvirga, Rubellimicrobium, Ellin6055, Sphingomonas, Massilia, Noviherbaspirillum | Bryobacter, Blastococcus, Arthrobacter, Pseudoarthrobacter, Rubrobacter, Flaviaesturariibacter, Segetibacter, Rhodocytophaga, Adhaeribacter, Pontibactor, AKIW781, AKYG1722, JG30-KF-CM45, Truepera, Planococcus, Saccharimonadales, Skermanella, Microvirga, Rubellimicrobium, Sphingomonas |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nejidat, A.; Diaz-Reck, D.; Zaady, E. Effect of Contamination by Phosphate Mining Effluent on Biocrust Microbial Community Structure and Cyanobacterial Diversity in a Hot Dry Desert. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2580. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13112580

Nejidat A, Diaz-Reck D, Zaady E. Effect of Contamination by Phosphate Mining Effluent on Biocrust Microbial Community Structure and Cyanobacterial Diversity in a Hot Dry Desert. Microorganisms. 2025; 13(11):2580. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13112580

Chicago/Turabian StyleNejidat, Ali, Damiana Diaz-Reck, and Eli Zaady. 2025. "Effect of Contamination by Phosphate Mining Effluent on Biocrust Microbial Community Structure and Cyanobacterial Diversity in a Hot Dry Desert" Microorganisms 13, no. 11: 2580. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13112580

APA StyleNejidat, A., Diaz-Reck, D., & Zaady, E. (2025). Effect of Contamination by Phosphate Mining Effluent on Biocrust Microbial Community Structure and Cyanobacterial Diversity in a Hot Dry Desert. Microorganisms, 13(11), 2580. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13112580