The Impact of Tourism on the Resilience of the Turkish Economy: An Asymmetric Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Data, Method and Hypotheses

4. Empirical Findings

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UNWTO. UN Tourism World Tourism Barometer|Global Tourism Statistics. 2024. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/un-tourism-world-tourism-barometer-data (accessed on 11 October 2024).

- UNWTO. World Tourism Barometer; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2024; Volume 22, pp. 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frechtling, D.C.; Horváth, E. Estimating the Multiplier Effects of Tourism Expenditures on a Local Economy through a Regional Input-Output Model. J. Travel Res. 1999, 37, 324–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathouraparsad, S.; Maurin, A. Measuring the Multiplier Effects of Tourism industry to the Economy. Adv. Manag. Appl. Econ. 2017, 7, 1792–7552. [Google Scholar]

- Nugraha, Y.E.; Flora, V.A.S.M. Economic Impact of Tourism Development in Coastal Area: A Multiplier Effect Analysis Approach. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Applied Science and Technology on Social Science (ICAST-SS 2021), Online, 4 March 2022; Atlantis Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascariu, G.C.; Ibănescu, B.C. Determinants and Implications of the Tourism Multiplier Effect in EU Economies. Towards a Core-Periphery Pattern? Amfiteatru Econ. 2018, 20, 982–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WTTC. Travel & Tourism Economic Impact|World Travel & Tourism Council (WTTC). Travel & Tourism Economic Impact. 2024. Available online: https://wttc.org/research/economic-impact (accessed on 11 October 2024).

- Fiksel, J. Sustainability and resilience: Toward a systems approach. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2006, 2, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oprisan, O.; Pirciog, S.; Ionascu, A.E.; Lincaru, C.; Grigorescu, A. Economic Resilience and Sustainable Finance Path to Development and Convergence in Romanian Counties. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, M.M. The Relationship Between Resilience and Sustainability in the Organizational Context—A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holling, C.S. Resilience and Stability of Ecological Systems. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1973, 4, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stallins, J.A.; Mast, J.N.; Parker, A.J. Resilience Theory and Thomas Vale’s Plants and People: A Partial Consilience of Ecological and Geographic Concepts of Succession. Prof. Geogr. 2015, 67, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brida, J.G.; Cortes-Jimenez, I.; Pulina, M. Has the tourism-led growth hypothesis been validated? A literature review. Curr. Issues Tour. 2016, 19, 394–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasool, H.; Maqbool, S.; Tarique, M. The relationship between tourism and economic growth among BRICS countries: A panel cointegration analysis. Future Bus. J. 2021, 7, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granger, C.W.; Yoon, G. Hidden Cointegration; Economics Working Paper, 02; University of California: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Cetin, M.K.; Sekreter, M.S.; Mert, M. The Effect of Price and Security on Tourism Demand: Panel Quantile Regression Approach. Adv. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2023, 11, 256–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, V. A study of the non-economic determinants in tourism demand. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2010, 12, 307–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, L.F.; Gan, Y.; Ferreira-Lopes, A. An empirical analysis of the influence of macroeconomic determinants on World tourism demand. Tour. Manag. 2017, 61, 248–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulucak, R.; Yücel, A.G.; İlkay, S.Ç. Dynamics of tourism demand in Turkey: Panel data analysis using gravity model. Tour. Econ. 2020, 26, 1394–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dȩbski, M.; Nasierowski, W. Criteria for the Selection of Tourism Destinations by Students from Different Countries. Found. Manag. 2017, 9, 317–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seddighi, H.R.; Theocharous, A.L. A model of tourism destination choice: A theoretical and empirical analysis. Tour. Manag. 2002, 23, 475–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. COVID-19 and Tourism|2020: A Year in Review. 2024. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/covid-19-and-tourism-2020 (accessed on 11 October 2024).

- TMCT. Republic of Turkiye Ministry of Culture and Tourism. 2024. Available online: https://yigm.ktb.gov.tr/TR-201121/isletme-bakanlik-belgeli-tesis-konaklama-istatistikleri.html (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- TUIK. TÜİK Kurumsal. 2024. Available online: https://data.tuik.gov.tr/Bulten/Index?p=Dis-Ticaret-Istatistikleri-Aralik-2023-49630 (accessed on 11 October 2024).

- TMCT. 2023 Turizmde Rekor Yılı Oldu, Republic of Turkiye Ministry of Culture and Tourism. 2024. Available online: https://basin.ktb.gov.tr/TR-365098/2023-turizmde-rekor-yili-oldu.html (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Buyuksarikulak, A.M.; Suluk, S. The Misery Index: An Evaluation on Fragile Five Countries. Abant Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi 2022, 22, 1108–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.P.; Wu, H.C.; Liu, S.B.; Wu, C.F.; Wu, Y.Y. Causality between global economic policy uncertainty and tourism in fragile five countries: A three-dimensional wavelet approach. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2022, 47, 608–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Review. Hanke’s 2023 Misery Index. 2024. Available online: https://www.nationalreview.com/2024/03/hankes-2023-misery-index/ (accessed on 5 November 2024).

- Scoones, I. Sustainability. Dev. Pract. 2007, 17, 589–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcuse, P. Sustainability is not enough. Environ. Urban. 1998, 10, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derissen, S.; Quaas, M.F.; Baumgärtner, S. The relationship between resilience and sustainability of ecological-economic systems. Ecol. Econ. 2011, 70, 1121–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiksel, J. Designing Resilient, Sustainable Systems. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2003, 37, 5330–5339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamieson, D. Sustainability and beyond. Ecol. Econ. 1998, 24, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kays, H.M.I.; Sadri, A.M. Towards Unifying Resilience and Sustainability for Transportation Infrastructure Systems: Conceptual Framework, Critical Indicators, and Research Needs. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2208.10039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, A. Resilience and sustainability in the face of disasters. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2011, 1, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, R.K.; Edwards, W.C.; Farrar, A.; Plodinec, M.J. A Practical Approach to Building Resilience in America’s Communities. Am. Behav. Sci. 2015, 59, 200–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchese, D.; Reynolds, E.; Bates, M.E.; Morgan, H.; Clark, S.S.; Linkov, I. Resilience and sustainability: Similarities and differences in environmental management applications. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 613–614, 1275–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carpenter, S.; Walker, B.; Anderies, J.M.; Abel, N. From Metaphor to Measurement: Resilience of What to What? Ecosystems 2001, 4, 765–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.L.; Zanotti, L.; Ma, Z.; Yu, D.J.; Johnson, D.R.; Kirkham, A.; Carothers, C. Interplays of Sustainability, Resilience, Adaptation and Transformation. In Handbook of Sustainability and Social Science Research; World Sustainability Series; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrings, C. Resilience in the dynamics of economy-environment systems. Environ. Resour. Econ. 1998, 11, 503–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations (UN). Sustainable Development Goals Report 2020; UN Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bogdański, M. Employment diversification as a determinant of economic resilience and sustainability in provincial cities. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lew, A.A.; Ng, P.T.; Ni, C.C.; Wu, T.C. Community sustainability and resilience: Similarities, differences and indicators. Tour. Geogr. 2016, 18, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, P.; Galaz, V.; Boonstra, W.J. Sustainability transformations: A resilience perspective. Ecol. Soc. 2014, 19, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutter, S.L.; Burton, C.G.; Emrich, C.T. Disaster resilience indicators for benchmarking baseline conditions. J. Homel. Secur. Emerg. Manag. 2008, 5, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallegatte, S. Economic Resilience: Definition and Measurement; World Bank Policy Research Working Paper; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2014; pp. 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cellini, R.; Cuccia, T. The economic resilience of tourism industry in Italy: What the “great recession” data show. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2015, 16, 346–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, E.W.; Wial, H.; Wolman, H. Exploring Regional Economic Resilience, Working Paper No. 2008,04. Institute of Urban and Regional Development. 2008. Available online: http://www.econstor.eu/handle/10419/59420 (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Alcalá-Ordóñez, A.; Brida, J.G.; Cárdenas-García, P.J. Has the tourism-led growth hypothesis been confirmed? Evidence from an updated literature review. Curr. Issues Tour. 2023, 27, 3571–3607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, L.; Forsyth, P. Measuring the benefits and yield from foreign tourism. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 1997, 24, 223–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, D.; Lew, A.A.; Ng, P.T. Tourism and Economic Growth. J. Travel Res. 2016, 55, 454–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwenhure, Y.; Odhiambo, N.M. Tourism and economic growth: A review of international literature. Tour. Int. Interdiscip. J. 2017, 65, 33–44. [Google Scholar]

- Calero, C.; Turner, L.W. Regional economic development and tourism: A literature review to highlight future directions for regional tourism research. Tour. Econ. 2020, 26, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.; Song, H.; Pyun, J.H. The relationship among tourism, poverty, and economic development in developing countries: A panel data regression analysis. Tour. Econ. 2016, 22, 1174–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deger, M.K. Turizme ve Ihracata Dayalı Büyüme: 1980–2005 Türkiye Deneyimi. Atatürk Üniversitesi İktisadi ve İdari Bilimler Dergisi 2006, 20, 67–86. [Google Scholar]

- Pablo-Romero, M.P.; Molina, J.A. Tourism and economic growth: A review of empirical literature. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2013, 8, 28–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brau, R.; Lanza, A.; Pigliaru, F. How Fast Are Tourism Countries Growing? The Cross Country Evidence; Working Paper CRENoS 2003(09); Centre for North South Economic Research, University of Cagliari and Sassari: Sardinia, Italy, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Songling, Y.; Ishtiaq, M.; Thanh, B.T. Tourism Industry and Economic Growth Nexus in Beijing, China. Economies 2019, 7, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, S.F.; Brida, J.G.; Risso, W.A. The impacts of international tourism demand on economic growth of small economies dependent on tourism. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assaf, A.G.; Josiassen, A. Identifying and Ranking the Determinants of Tourism Performance: A Global Investigation. J. Travel Res. 2012, 51, 388–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chomać-Pierzecka, E.; Stasiak, J. Domestic Tourism Preferences of Polish Tourist Services’ Market in Light of Contemporary Socio-economic Challenges. In Strategic Innovative Marketing and Tourism. ICSIMAT 2023; Kavoura, A., Borges-Tiago, T., Tiago, F., Eds.; Springer Proceedings in Business and Economics; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuković, D.B.; Maiti, M.; Petrović, M.D. Tourism Employment and Economic Growth: Dynamic Panel Threshold Analysis. Mathematics 2023, 11, 1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, P.; Deller, S. Tourism and economic resilience. Tour. Econ. 2022, 28, 1193–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.P.; Wu, H.C.; Liu, Y.T.; Wu, Y.Y. An empirical asymmetric effect of the tourism-led growth hypothesis in the Chinese economy. J. Policy Res. Tour. Leis. Events 2023, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R.; Seetanah, B.; Jaffur, Z.R.K.; Moraghen, P.G.W.; Sannassee, R.V. Tourism and Economic Growth: A Meta-regression Analysis. J. Travel Res. 2020, 59, 404–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsalobre-Lorente, D.; Driha, O.M.; Bekun, F.V.; Adedoyin, F.F. The asymmetric impact of air transport on economic growth in Spain: Fresh evidence from the tourism-led growth hypothesis. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 503–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyuboglu, S.; Eyuboglu, K. Tourism development and economic growth: An asymmetric panel causality test. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 659–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.N.; Patel, A.; Kimpton, S.; Andrews, A. Asymmetric reactions in the tourism-led growth hypothesis. Aust. Econ. Pap. 2022, 61, 661–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gülbahar, Y. 1990’lardan Günümüze Türkiye’de Kitle Turizminin Gelişimi ve Alternatif Yönelimler. Süleyman Demirel Üniversitesi İktisadi Ve İdari Bilimler Fakültesi Dergisi 2009, 14, 151–177. [Google Scholar]

- Okuyucu, A.; Akgiş, Ö. Türkiye’de Konaklama Sektörünün Yapisal ve Mekânsal Değişimi: 1990–2013. Türkiye Sos. Araştırmalar Derg. 2016, 20, 249–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Işik, C. The USA’s International Travel Demand and Economic Growth in Turkey: A Causality Analysis: (1990–2008). Tourismos 2012, 7, 235–252. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, P.C.B.; Perron, P. Testing for a Unit Root In Time Series Regression. Biometrika 1988, 75, 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zivot, E.; Andrews, D.W.K. Further Evidence on the Great Crash, the Oil-Price Shock, and the Unit-Root Hypothesis. J. Bus. Econ. Stat. 2002, 20, 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enders, W.; Lee, J. The flexible Fourier form and Dickey-Fuller type unit root tests. Econ. Lett. 2012, 117, 196–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatemi-J, A. Asymmetric Causality Tests with an Application. Empir. Econ. 2012, 43, 447–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mert, M.; Çağlar, A.E. Testing pollution haven and pollution halo hypotheses for Turkey: A new perspective. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 32933–32943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engle, R.F.; Granger, C.W.J. Co-integration and error correction: Representation, estimation, and testing. Econom. J. Econom. Soc. 1987, 55, 251–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honarvar, A. Asymmetry in retail gasoline and crude oil price movements in the United States: An application of hidden cointegration technique. Energy Econ. 2009, 31, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mert, M.; Çağlar, A.E. Eviews ve Gauss Uygulamalı Zaman Serileri Analizi, 2nd ed.; Detay Yayıncılık: Ankara, Turkey, 2023; ISBN 978-605-254-126-5. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalo, J.; Granger, C. Estimation of common long-memory components in cointegrated systems. J. Bus. Econ. Stat. 1995, 13, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, M.C. Does tourism development promote economic growth in transition countries? A panel data analysis. Econ. Model. 2013, 33, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dritsakis, N. Tourism development and economic growth in seven Mediterranean countries: A panel data approach. Tour. Econ. 2012, 18, 801–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eugenio-Martin, J.L.; Martín Morales, N.; Scarpa, R. Tourism and Economic Growth in Latin American Countries: A Panel Data Approach. SSRN Electron. J. 2011, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.C.; Chang, C.P. Tourism development and economic growth: A closer look at panels. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 180–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seetanah, B. Assessing the dynamic economic impact of tourism for island economies. Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 291–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Turkey Overview: Development News, Research, Data|World Bank. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/turkey/overview (accessed on 25 December 2024).

- Ernst & Young. Tourism Update 2023—Türkiye and İstanbul. Tourism Update 2023. 2023. Available online: https://www.ey.com/tr_tr/technical/ey-turkiye-yayinlar-raporlar/ey-turizm-sektoru-2023-degerlendirmesi (accessed on 11 October 2024).

- Ibrar, H. An analysis of the asymmetric effect of fiscal policy on economic growth in Pakistan: Insights from Non-Linear ARDL. IBA Bus. Rev. 2020, 15, 19–49. [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal, J.; Nosheen, M.; Ahmed, S.; Shil, N.C. Beyond symmetry: Investigating the asymmetric impact of exchange rate misalignment on economic growth dynamics in Bangladesh. Macroecon. Financ. Emerg. Mark. Econ. 2024, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.-Y.L. Reexamining Asymmetric Effects of Monetary and Government Spending Policies on Economic Growth Using Quantile Regression. J. Dev. Areas 2009, 43, 137–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruf, A.; Masih, M. Is the Relationship Between Infrastructure and Economic Growth Symmetric or Asymmetric? Evidence from Indonesia Based on Linear and Non-Linear ARDL; MPRA Paper, 94663; University Library of Munich: Munich, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Olya, H. The combined use of symmetric and asymmetric approaches: Partial least squares-structural equation modeling and fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 33, 1571–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.J.A.; Kim, J.; Jang, S.; Ash, K.; Yang, E. Tourism and economic resilience. Ann. Tour. Res. 2021, 87, 103024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, S.J.H.; Shahbaz, M.; Ferrer, R.; Kumar, R.R. Tourism-led growth hypothesis in the top ten tourist destinations: New evidence using the quantile-on-quantile approach. Tour. Manag. 2017, 60, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslan, A. Tourism development and economic growth in the Mediterranean countries: Evidence from panel Granger causality tests. Curr. Issues Tour. 2014, 17, 363–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunduz, L.; Hatemi-J, A. Is The Tourism-Led Growth Hypothesis Valid for Turkey? Appl. Econ. Lett. 2005, 12, 499–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ongan, S.; Demiröz, D.M. The contribution of tourism to the long-run Turkish economic growth. Ekon. Cas. 2005, 53, 880–894. [Google Scholar]

- Arslanturk, Y.; Balcilar, M.; Ozdemir, Z.A. Time-varying linkages between tourism receipts and economic growth in a small open economy. Econ. Model. 2011, 28, 664–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katircioglu, S.T. Revising the tourism-led-growth hypothesis for Turkey using the bounds test and Johansen approach for cointegration. Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.T.; Saboori, B.; Ranjbar, O.; Can, M. Global Perspective on Tourism-Economic Growth Nexus: The Role of Tourism Market Diversification. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2023, 20, 919–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agazade, S. The effect of tourism source market structure on international tourism revenues in Turkey. Tour. Econ. 2021, 28, 714–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romão, J. Tourism, smart specialisation, growth, and resilience. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 84, 102995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNEP; WTO. Making Tourism More Sustainable: A Guide for Policy Makers. United Nations Environment Programme and World Tourism Organization. 2005. Available online: https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/8741/-Making%20Tourism%20More%20Sustainable_%20A%20Guide%20for%20Policy%20Makers-2005445.pdf?sequence=3&%3BisAllowed= (accessed on 31 December 2024).

- Butler, R.W. Sustainable tourism: A state-of-the-art review. Tour. Geogr. 1999, 1, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

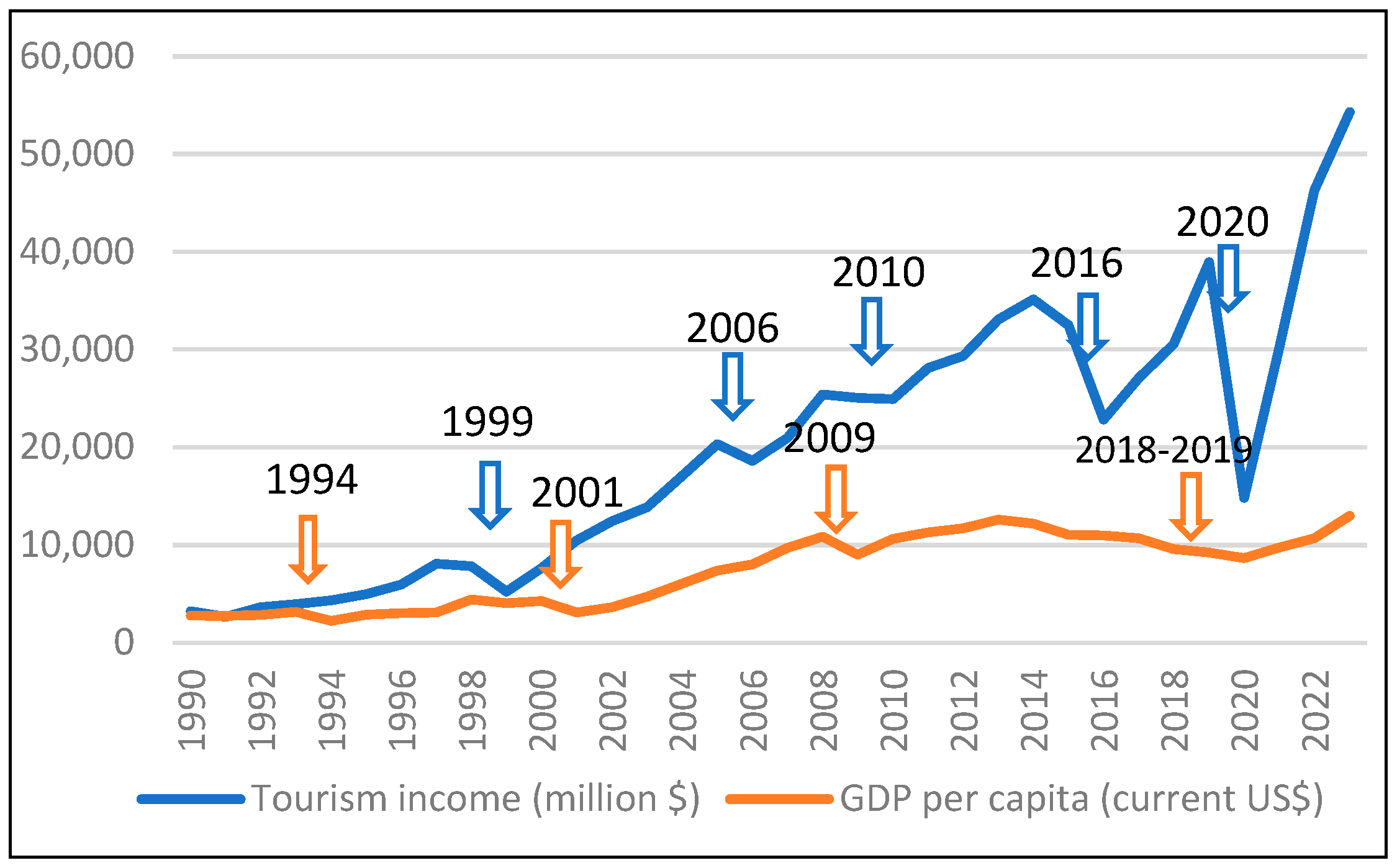

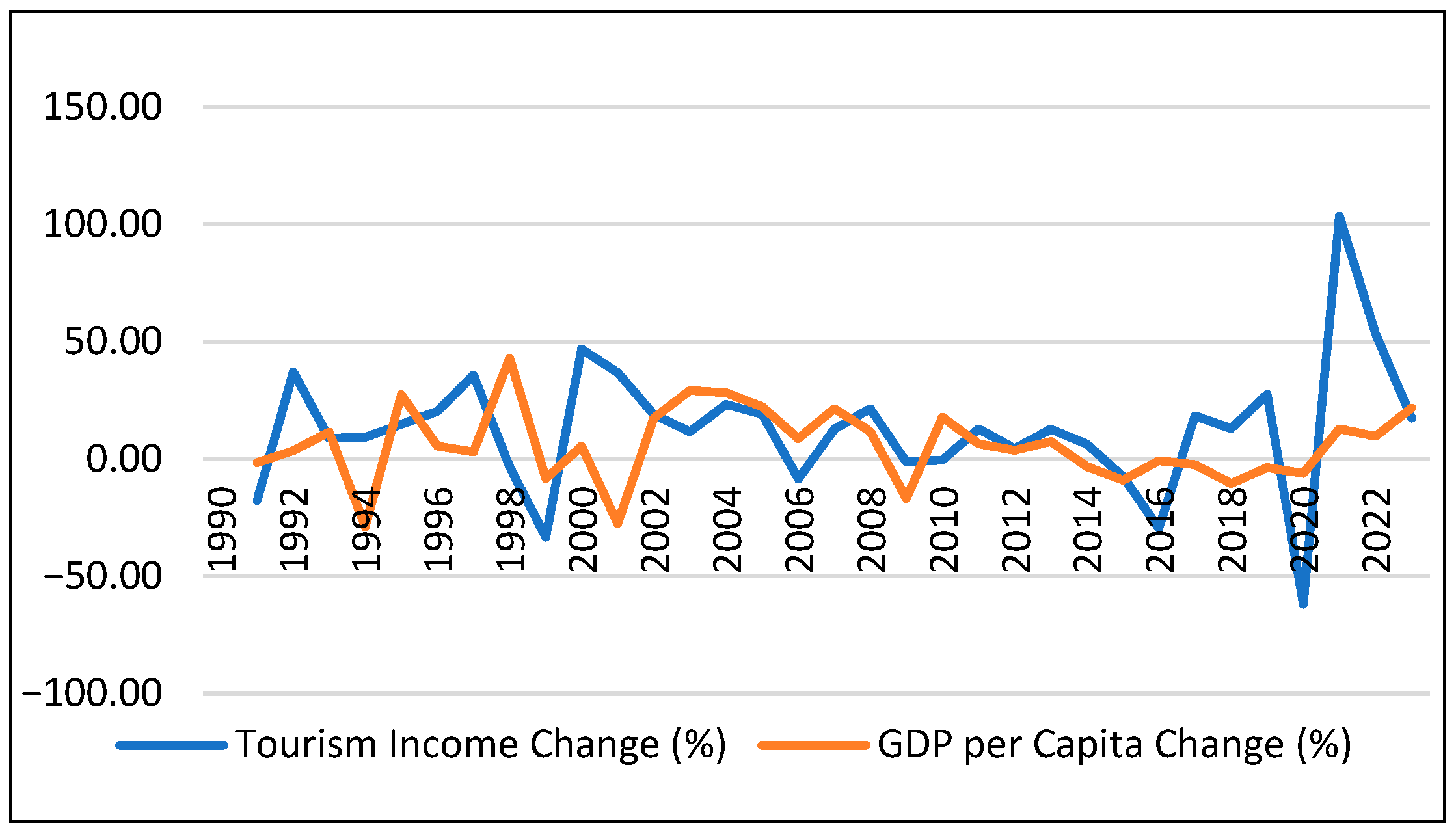

| Year | Crisis or Events |

|---|---|

| 1994 | Turkey’s economic crisis Political instability High inflation Currency crisis High borrowing costs of government |

| 1999 | Marmara earthquake Political and economic stability Security concerns—terrorist activities 1998 Asian financial crisis |

| 2001 | Turkey’s economic crisis Global economic slowdown (dot-com bubble burst) September 11 attacks—security concerns globally Regional instability Middle-East |

| 2006 | Health concerns avian flu outbreak Regional instability Middle-East Security concerns—terrorist activities Increased competition (such as Greece, Spain, Croatia) Exchange rate fluctuations |

| 2009 | Impact of 2008 global financial crisis Export crisis (esp. to European Union) Reduction in investments/decline in capital flows Decline in domestic demand/industrial production |

| 2010 | Global economic uncertainty Low-budget tourism Increased competition (such as Greece, Spain, Egypt) Currency fluctuations (expensive destination) |

| 2016 | Security concerns—terrorist activities—failed coup attempt Turkey–Russia tensions Regional instability—Middle East Economic and political uncertainty |

| 2018–2019 | Political tension with US High external debt Inflation and current account deficit |

| 2020 | COVID-19 pandemic restrictions Economic recession and financial uncertainty Shift in travel behavior to local tourism |

| Case | Sign * | Shocks of TOI | Shocks of GDP | Hypothesis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Enhancing effect | |||

| 2 | Inhibiting effect | |||

| 3 | Parachute effect | |||

| 4 | Exacerbating effect |

| PP Test | Adj. t-stat | Critical Value | |||

| −1.781 | −4.27 | ||||

| −5.761 * | −4.28 | ||||

| −2.584 | −4.27 | ||||

| −14.836 * | −4.28 | ||||

| ZA Test | t-stat | Lag | Critical Value | ||

| −3.668 | 2004 | 0 | −5.57 | ||

| −4.388 | 2008 | 0 | −5.57 | ||

| F-ADF Test | Lag | Critical Value | |||

| 0 | 1 | 3.848 | 12.21 | −2.627 | |

| 0 | 1 | 6.162 | 12.21 | −4.371 |

| Bootstrap Critical Values (10,000 Replications) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HJ Test | Wald Stat. | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.10 |

| 90.728 ** | 115.198 | 39.177 | 22.361 | |

| 0.852 | 10.522 | 5.288 | 3.422 | |

| 4.617 * | 12.760 | 5.605 | 3.608 | |

| 110.986 ** | 32.147 | 11.797 | 7.433 | |

| 14.184 | 81.277 | 25.765 | 15.238 | |

| 0.380 | 87.651 | 26.493 | 16.010 | |

| 5.334 | 92.034 | 29.228 | 17.405 | |

| 0.020 | 24.876 | 10.007 | 6.529 | |

| Null: No Co-Integration | ||||

| tau Stat. | p-Value | z Stat | p-Value | |

| −2.99 | 0.139 | −16.36 * | 0.063 | |

| Long run equation | ||||

| Coeff. | HAC St. Error | t Stat | p-Value | |

| Cons. | −0.0835 | 0.206 | −0.40 | 0.687 |

| −0.2932 ** | 0.123 | −2.37 | 0.023 | |

| CECM | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sekreter, M.S.; Mert, M.; Cetin, M.K. The Impact of Tourism on the Resilience of the Turkish Economy: An Asymmetric Approach. Sustainability 2025, 17, 591. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17020591

Sekreter MS, Mert M, Cetin MK. The Impact of Tourism on the Resilience of the Turkish Economy: An Asymmetric Approach. Sustainability. 2025; 17(2):591. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17020591

Chicago/Turabian StyleSekreter, Mehmet Serhan, Mehmet Mert, and Mustafa Koray Cetin. 2025. "The Impact of Tourism on the Resilience of the Turkish Economy: An Asymmetric Approach" Sustainability 17, no. 2: 591. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17020591

APA StyleSekreter, M. S., Mert, M., & Cetin, M. K. (2025). The Impact of Tourism on the Resilience of the Turkish Economy: An Asymmetric Approach. Sustainability, 17(2), 591. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17020591