Eucalyptus nitens Wood of Spanish Origin as Timber Bioproduct: Fiber Saturation Point and Dimensional Variations

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Raw Material and Measurement

2.2. Experimental Method

2.3. Calculations and Analytical Tools of Analyzed Properties

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hamilton, M.G.; Blackburn, D.P.; McGavin, R.L.; Baillères, H.; Vega, M.; Potts, B.M. Factors affecting log traits and green rotary-peeled veneer recovery from temperate eucalypt plantations. Ann. For. Sci. 2015, 72, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consellería Medio Rural. Xunta de Galicia. Law 140/2021, of September 30. First Revision of the Galicia Forestry Plan 2021–2040, Towards Carbon Neutrality. Revisión de Plan Forestal de Galicia. 2021. Available online: https://mediorural.xunta.gal/sites/default/files/temas/forestal/plan-forestal/PFG-DEFINITIVO_castelan.pdf (accessed on 29 July 2025). (In Spanish).

- Muñoz Saez, F. Evaluation of Silvicultural Practices in Eucalyptus nitens Deane & Maiden Plantations (Evaluación de Prácticas Silvícolas en Plantaciones de Eucalyptus nitens Deane & Maiden Maiden). Ph.D. Thesis, University of Granada, Granada, Spain, 2006. Available online: https://www.educacion.gob.es/teseo/imprimirFichaConsulta.do?idFicha=130037 (accessed on 15 April 2025). (In Spanish).

- González-García, M.; Hevia, A.; Majada, J.; Rubiera, F.; Barrio-Anta, M. Nutritional, carbon and energy evaluation of Eucalyptus nitens short rotation bioenergy plantations in northwestern Spain. iForest-Biogeosciences For. 2015, 9, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ananías, R.; Sepúlveda-Villarroel, V.; Pérez-Peña, N.; Torres-Mella, J.; Salvo-Sepúlveda, L.; Casti-llo-Ulloa, D.; Salinas-Lira, C. Radio Frequency Vacuum Drying of Eucalyptus nitens Juvenile Wood. BioResources 2020, 15, 4886–4897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-García, M. Modeling the Biomass Production of Eucalyptus nitens (Deane & Maiden) Maiden in Short Rotation for Energy Crop (Modelización de la Producción de Biomasa de Eucalyptus nitens (Deane & Maiden) Maiden en Corta Rotación para Cultivo Energético). Ph.D. Thesis, University of Oviedo, Oviedo, Sapin, 2015. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10651/33202 (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Cheng, Y.; Nolan, G.; Holloway, D.; Kaur, J.; Lee, M.; Chan, A. Flexural characteristics of Eucalyptus nitens timber with high moisture content. Bioresources 2021, 16, 2921–2936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmann, F.F.P.; Côté, W.A. Principles of Wood Science and Technology: I, Solid Wood; Springer-Verlag: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1968; 592p, ISBN 9783642879302. Available online: https://www.springer.com/gp/book/9783642879302 (accessed on 28 October 2024).

- Dinwoodie, J.M. Timber: Its Nature and Behavior, 2nd ed.; Taylor & Francis Group: Abingdon, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiemann, H.D. Effect of Moisture Upon the Strength and Stiffness of Wood; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service: Washington, DC, USA, 1906; 144p. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/2027/hvd.32044102823747 (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Babiak, M.; Kúdela, J. A contribution to the definition of the fiber saturation point. Wood Sci. Technol. 1995, 29, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glass, S.V.; Zelinka, S.L. Moisture relations and physical properties of wood. In Wood Handbook: Wood as an Engineering Material; Centennial Edition; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Forest Products Laboratory: Madison, WI, USA, 2010; Chapter 4. Available online: https://research.fs.usda.gov/treesearch/62243 (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Passarini, L.; Malveau, C.; Hernandez, R.E. Water state study of wood structure of four hardwoods below fiber saturation point with nuclear magnetic resonance. Wood Fiber Sci. 2014, 46, 480–488. Available online: https://wfs.swst.org/index.php/wfs/article/view/915/915 (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- Almeida, G.; Hernandez, R.E. Influence of the pore structure of wood on moisture desorption at high relative humidities. Wood Mat. Sci. Eng. 2007, 2, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, G.; Hernandez, R.E. Changes in physical properties of tropical and temperate hardwoods below and above the fiber saturation point. Wood Sci. Technol. 2006, 40, 599–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, J.R. Wood Handbook: Wood as an Engineering Material; General Technical Report FPL-GTR-190; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Forest Products Laboratory: Madison, WI, USA, 2010; Volume 1, 509p. [CrossRef]

- Ananías, R.A.; Sepúlveda-Villarroel, V.; Pérez-Peña, N.; Leandro-Zuñiga, L.; Salvo-Sepúlveda, L.; Salinas-Lira, C.; Cloutier, A.; Elustondo, D.M. Collapse of Eucalyptus nitens wood after drying depending on the radial location within the stem. Dry. Technol. 2014, 32, 1699–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chafe, S.C.; Barnacle, J.E.; Hunter, A.J.; Ilic, J.; Northway, R.L.; Rozsa, A.N. Collapse: An Introduction; CSIRO Division of Forest Products: Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 1992; p. 9. ISBN 9780643054417. Available online: https://books.google.es/books?id=SYzdAAAACAAJ (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- Berry, S.L.; Roderick, M.L. Plant–water relations and the fibre saturation point. New Phytol. 2005, 168, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredriksson, M.; Thybring, E.E.; Zelinka, S.L.; Glass, S.V. The fiber saturation point: Does it mean what you think it means? Cellulose 2025, 32, 2901–2918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahri, H.; Jusoh, Z.; Ashaari, Z.; Apin, L. Fibre Saturation Point of Lesser-Known Timbers from Sabah. Pertanika J. Trop. Agric. Sci. 1998, 21, 67–71. [Google Scholar]

- Montero, C.; Rozas, C. Exploratory study for the characterization of the wood drying rate of Eucalyptus nitens timber, applying multiple regression models—Estudio exploratorio para la caracterización de la tasa de secado de la madera de Eucalyptus nitens, aplicando modelos de regresión multiple. Sci. For. 2019, 47, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ananias, R.A.; Díaz, C.; Leandro, L. Preliminary study of shrinkage and collapse in Eucalyptus nitens—Estudio preliminar de la contracción y el colapso en Eucalyptus nitens. Maderas-Cienc. Tecnol. 2009, 11, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Esteban, L. La Madera y Su Tecnología: Aserrado, Chapa, Tableros Contrachapados, Tableros de Partículas y de Fibras, Tableros OSB y LVL, Madera Laminada, Carpintería, Corte y Aspiración; Mundi-Prensa: Madrid, Spain, 2002; 336p, ISBN 9788484760368. Available online: https://books.google.es/books?id=NfQxAAAACAAJ (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Jankowska, A.; Kozakiewicz, P. Determination of fibre saturation point of selected tropical wood species using different methods. Drewno 2016, 59, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igartúa, D.V.; Monteoliva, S.; Piter, J.C. Estudio de algunas propiedades físicas de la madera de Acacia melanoxylon en Argentina. Maderas-Cienc. Tecnol. 2009, 11, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Prieto, O.; Medina, G. Mermas longitudinales en tarimas de exterior (deckings). Boletín Inf. Técnica AITIM 2011, 276, 42–44. [Google Scholar]

- Stamm, A.J. Review of nine methods for determining the fiber saturation points of wood and wood products. Wood Sci. 1971, 4, 114–128. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, G. Influence of wood structure on moisture desorption and changes in its properties above the fiber saturation point. In Proceedings of the SWST 48th Annual Convention, Québec City, QC, Canada, 19 June 2005; Available online: http://www.swst.org/wp/meetings/AM05/almeida.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Hernández, R.E.; Bizoň, M. Changes in shrinkage and tangential compression strength of sugar maple below and above the fiber saturation point. Wood Fiber Sci. 2007, 26, 360–369. [Google Scholar]

- Siau, J.F. Wood: Influence of Moisture on Physical Properties; Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University: Blacksburg, VA, USA, 1995; 227p, ISBN 9780962218101. Available online: https://books.google.es/books?id=fErxAAAAMAAJ (accessed on 8 February 2025).

- Fernández-Golfín Seco, J.I.; Conde García, M. Manual Técnico de Secado de la Madera; AITIM: Madrid, Spain, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Opazo-Vega, A.; Rosales-Garcés, V.; Oyarzo-Vera, C. Non-Destructive assessment of the dynamic elasticity modulus of Eucalyptus nitens timber boards. Materials 2021, 14, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinley, R.B.; Shelbourne, C.J.A.; Low, C.B.; Penellum, B.; Kimberley, M.O. Wood properties of young Eucalyptus nitens, E. globulus, and E. maidenii in Northland, New Zealand. NZJ For. Sci. 2002, 32, 334–356. [Google Scholar]

- García Esteban, L.; Guindeo Casasús, A.; Peraza Oramas, C.; De Palacios, P. La Madera y su Tecnología; AITIM: Madrid, Spain, 2002; ISBN 9788484760368. [Google Scholar]

- IRAM 9543; Método de Determinación de las Contracciones Totales, Radial y Tangencial y el Punto de Saturación de las Fibras. Instituto Argentino de Racionalización de Materiales: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1966. Available online: https://catalogo.iram.org.ar/#/normas/detalles/7169 (accessed on 14 November 2024).

- DIN 52184; Testing of Wood; Determination of Swelling and Shrinkage. German Institute for Standardisation: Berlin, Germany, 1979. Available online: https://www.din.de/de/mitwirken/normenausschuesse/nhm/wdc-beuth:din21:625145 (accessed on 14 November 2024).

- Calvo, C.F.; Cotrina, A.D.; Cuffré, A.G.; Piter, J.C.; Stefani, P.M.; Torrán, E.A. Radial and axial variation of swelling, anisotropy and density in Argentinean Eucalyptus Grandis. Maderas-Cienc. Tecnol. 2006, 8, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, G. El concepto estadístico de centro de gravedad. Números. Rev. Didáct. Mat. 2003, 53, 43–53. [Google Scholar]

- García, N.A. Elementos de Bioestadística. In Colección Manual UEX, 3rd ed.; Universidad de Extremadura, Servicio de Publicaciones: Cáceres, Spain, 2011; Volume 79, p. 29. ISBN 978-84-694-9432-5. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/libro?codigo=678354 (accessed on 17 March 2025). (In Spanish)

- Keey, R.; Langrish, T.; Walker, J. Kiln-Drying of Lumber; Springer Verlag: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2000; 289p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, B.S.W.; Pearson, H.; Kimberley, M.O.; Davy, B.; Dickson, A.R. Effect of supercritical CO2 treatment and kiln drying on collapse in Eucalyptus nitens wood. Eur. J. Wood Wood Prod. 2020, 78, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Cheng, Y.; Chan, A.; Holloway, D.; Nolan, G. Anisotropic Tensile Characterisation of Eucalyptus nitens Timber above Its Fibre Saturation Point, and Its Application. Polymers 2022, 14, 2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redman, A.L.; Bailleres, H.; Turner, I.; Perre, P. Characterisation of wood–water relationships and transverse anatomy and their relationship to drying degrade. Wood Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 739–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslett, A.N. Properties and utilisation of exotic speciality timbers grown in New Zealand. Part VI: Eastern blue gums and stringy barks. Eucalyptus botryoides Sm. Eucalyptus saligna Sm. Eucalyptus globoidea Blakey. Eucalyptus muellerana Howitt. Eucalyptus pilularis Sm. FRI Bull. 1990, 119, 21. [Google Scholar]

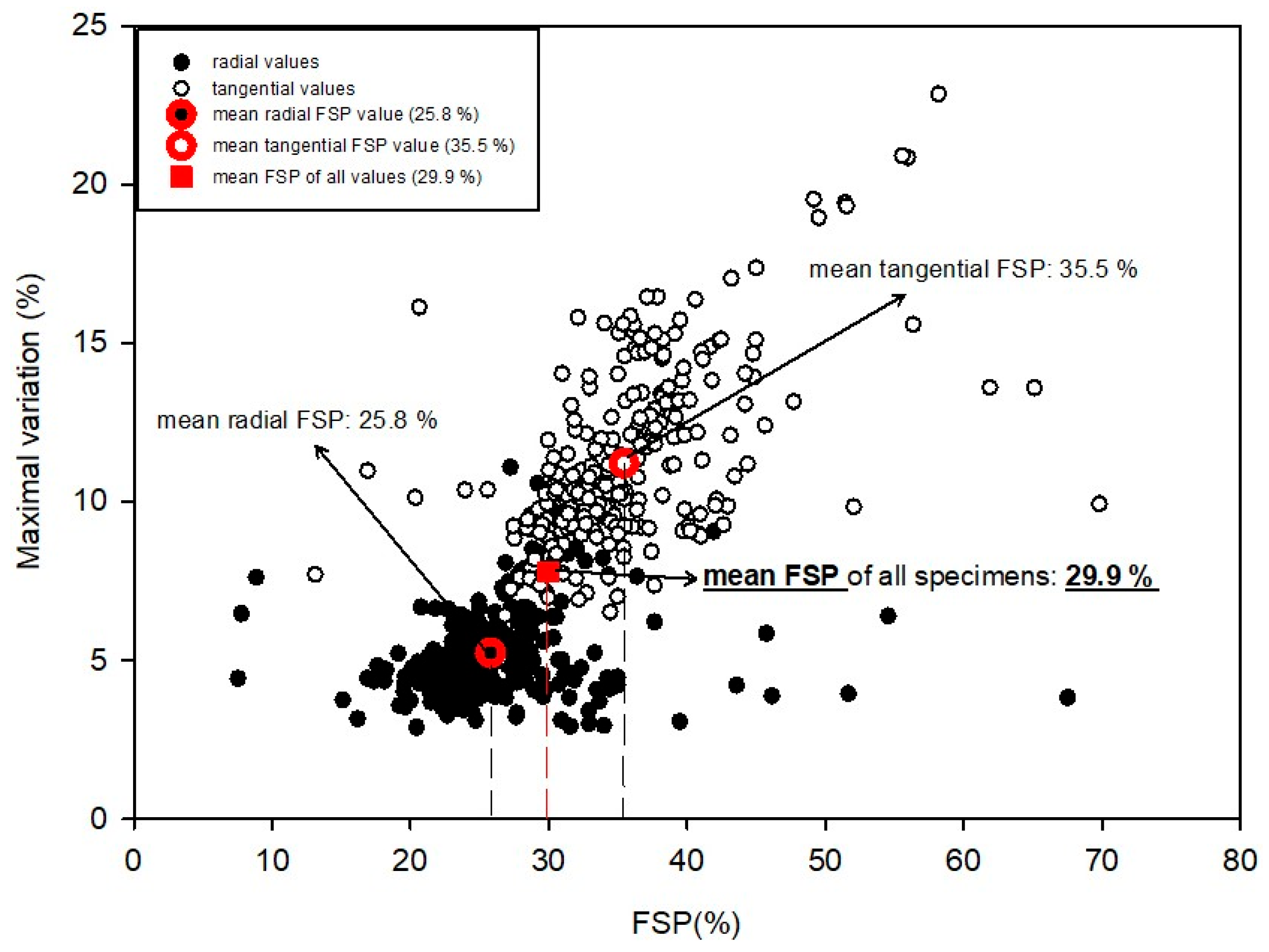

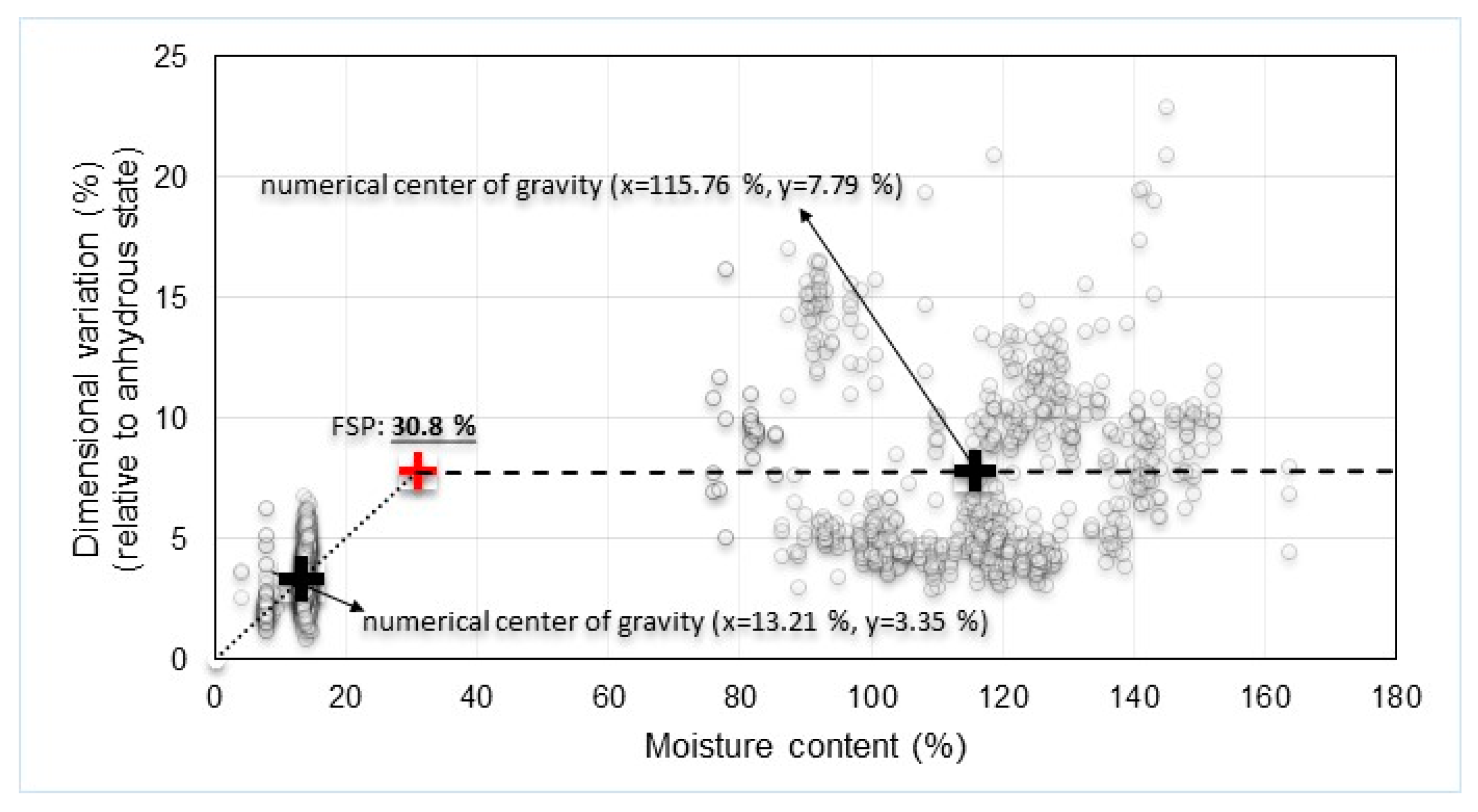

| Mean Values with Anomalous Data | Equation | Radial Direction | Tangential Direction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total variation, saturated * to anhydrous ** (%) | 1 | 5.2 [±1.53] | 11.2 [±2.84] |

| Saturated MC (%) | 4 | 116.0 [±15.08] | 115.5 [±23.34] |

| Normal conditions *** to anhydrous ** state variation (%) | 2 | 2.8 [±0.70] | 4.0 [±1.27] |

| Normal conditions *** MC (%) | 4 | 13.8 [±0.96] | 12.5 [±2.63] |

| Average FSP | 3 | 25.8 [±5.46] | 35.5 [±7.38] |

| Average FSP of all values | 29.9 [±7.95] | ||

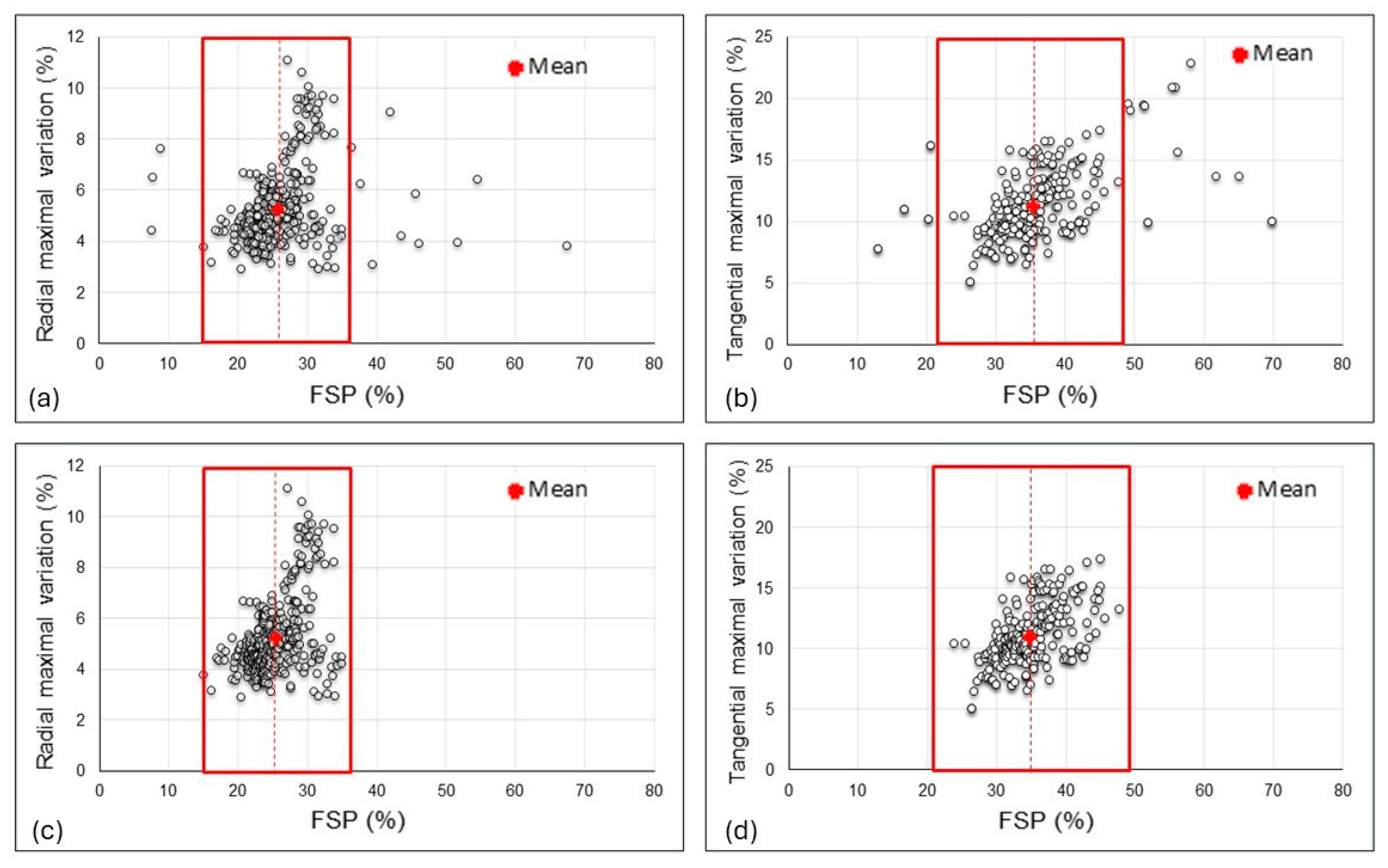

| Mean Values Without Anomalous Data | Equation | Radial Direction | Tangential Direction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total variation, saturated * to anhydrous ** (%) | 1 | 5.2 ± [1.52] | 10.9 ± [2.42] |

| Saturated MC (%) | 4 | 115.8 ± [14.86] | 116.5 ± [22.58] |

| Normal conditions *** to anhydrous ** state variation (%) | 2 | 2.9 ± [0.67] | 4.0 ± [1.22] |

| Normal conditions *** MC (%) | 4 | 13.9 ± [0.36] | 12.7 ± [2.50] |

| Average FSP | 3 | 25.3 ± [3.61] | 34.8 ± [4.35] |

| Average FSP of all values | 29.3 ± [6.10] | ||

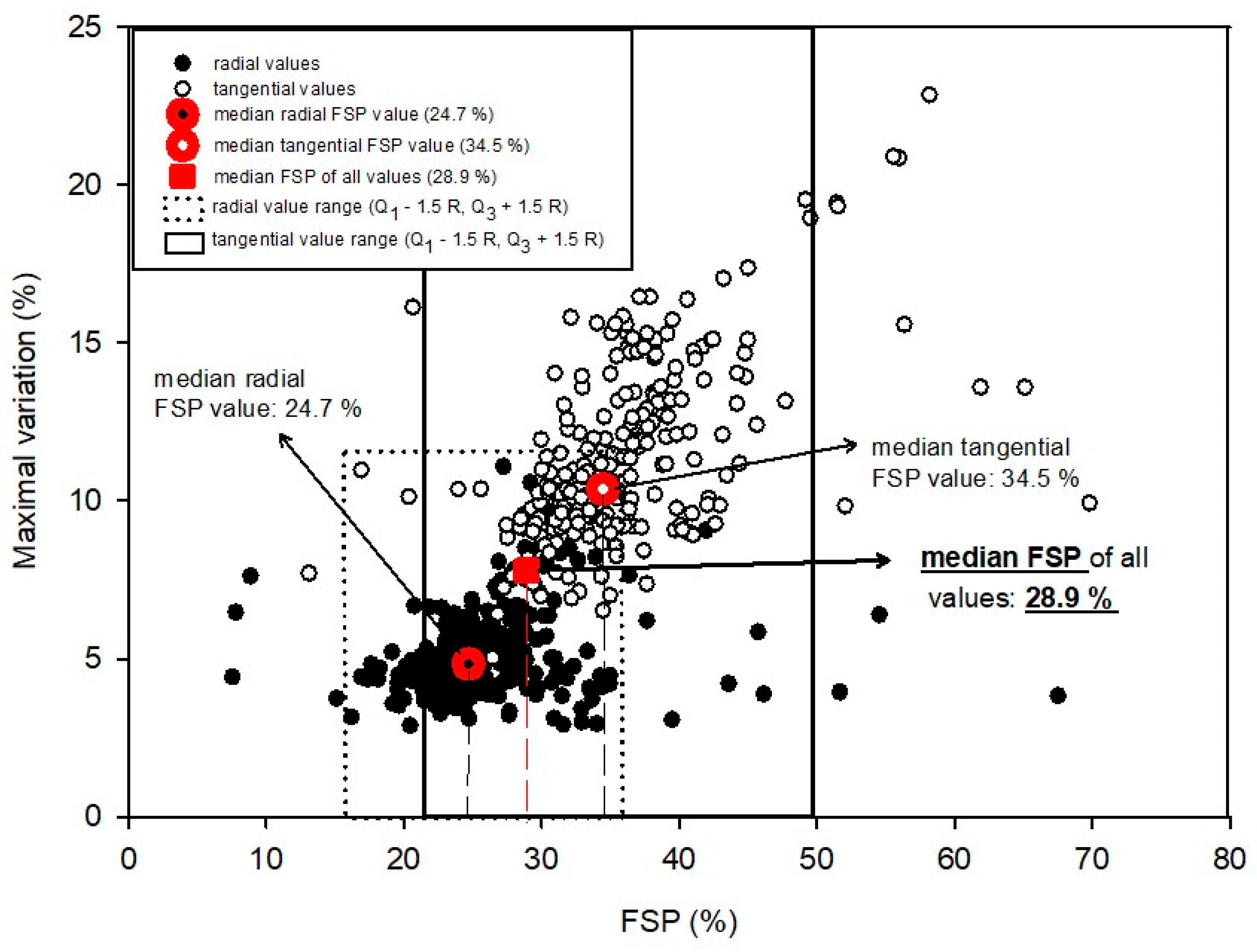

| Values of Median Data | Equation | Radial Direction | Tangential Direction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total variation, saturated * to anhydrous ** (%) | 1 | 4.8 | 10.4 |

| Saturated MC (%) | 4 | 116.8 | 121.4 |

| Normal conditions *** to anhydrous ** state variation (%) | 2 | 2.8 | 4.3 |

| Normal conditions *** MC (%) | 4 | 13.9 | 13.9 |

| Average FSP | 3 | 24.7 | 34.5 |

| Average FSP of all values | 28.9 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

González-Prieto, Ó.; Casais Goimil, D.; Ortiz Torres, L. Eucalyptus nitens Wood of Spanish Origin as Timber Bioproduct: Fiber Saturation Point and Dimensional Variations. Bioresour. Bioprod. 2025, 1, 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioresourbioprod1020009

González-Prieto Ó, Casais Goimil D, Ortiz Torres L. Eucalyptus nitens Wood of Spanish Origin as Timber Bioproduct: Fiber Saturation Point and Dimensional Variations. Bioresources and Bioproducts. 2025; 1(2):9. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioresourbioprod1020009

Chicago/Turabian StyleGonzález-Prieto, Óscar, David Casais Goimil, and Luis Ortiz Torres. 2025. "Eucalyptus nitens Wood of Spanish Origin as Timber Bioproduct: Fiber Saturation Point and Dimensional Variations" Bioresources and Bioproducts 1, no. 2: 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioresourbioprod1020009

APA StyleGonzález-Prieto, Ó., Casais Goimil, D., & Ortiz Torres, L. (2025). Eucalyptus nitens Wood of Spanish Origin as Timber Bioproduct: Fiber Saturation Point and Dimensional Variations. Bioresources and Bioproducts, 1(2), 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioresourbioprod1020009