1. Introduction

The automobile sector is considered as a strategic support for the global economy. It is among one of the most challenging manufacturing sectors, with over three million workers in Europe alone [

1]. Working conditions in the automobile sector are characterized by high production pressure, rapid technological change, repetitive work, and irregular shift work. These factors could lead to both physical and mental problems among workers. Physically, employees are particularly exposed to musculoskeletal disorders and fatigue due to repetitive and physically demanding work [

1,

2]. Psychologically, research has shown elevated stress levels and burnout among factory workers, highlighting the negative impact of job demands on workers’ well-being [

3]. Such outcomes not only affect employees’ health but also contribute to absenteeism and lower job satisfaction at the organizational level [

1,

4]. In such environments, support from workers, particularly in the workplace, can constitute an important source of protection, therefore capable of counteracting the negative effects of job demands on stress and on Satisfaction with Life [

4].

The organizational support function in safeguarding employee health in high-demand sectors such as automotive assembly can be described from several synergistic theoretical perspectives. The Job Demands–Resources model emphasizes how organizational support functions as a job resource that counterbalances the stress caused by high production demands, irregular schedules, and rapid technological change—all typical characteristics of the sector [

5]. Social Support Theory complements this framework by identifying the distinct modalities of support (emotional, instrumental, informational, and appraisal) that can address different facets of stress and foster well-being. Conservation of Resources Theory (COR) extends this view by conceptualizing support as a reservoir of psychological and social resources that not only buffer strain but also sustain Satisfaction with Life over time [

6]. These three models were selected because, together, they provide complementary insights into both the immediate and the enduring protective effects of organizational support in the automotive industry.

These arguments are theoretically supported by empirical studies in automobile factory environments. As such, workers tend to report lower stress levels and high job satisfaction amidst high production demands when the organizational environment promotes safety, open communication, and availability of resources [

7]. Likewise, similar findings in large factories show that positive practices can undermine the adverse connection between job stress and Satisfaction with Life, enabling employees to retain a more optimistic attitude in spite of challenging circumstances [

8].

Previous research in the automotive sector has shown high exposure to stress, burnout, and psychosocial risks, with organizational practices playing a critical role in mitigating adverse outcomes [

3,

7,

8]. In parallel, studies across different occupational groups confirm that organizational support is a key protective factor against work-related stress and a predictor of well-being [

4,

9,

10,

11]. However, evidence remains scarce regarding the interplay between organizational support, perceived stress, and Satisfaction with Life in the automotive industry. In Portugal, research has examined coping, mental health, and Satisfaction with Life in broader worker samples [

12], but not in automotive settings, where production pressures and organizational demands are more dynamic and intense. Furthermore, while economic and industrial aspects of the Portuguese automotive sector have been well studied [

13], psychosocial correlates remain largely overlooked. Addressing this gap, the present study investigates the potential indirect effect of organizational support on the association between stress and Satisfaction with Life among Portuguese automotive workers, thereby contributing novel evidence to both the national and European contexts.

In addition, studies that examine organizational support in the work environment tend to investigate its effect on stress or Satisfaction with Life rather than examining potential variables that could also indirectly affect the relationship between Satisfaction with Life and Perceived Stress [

14]. Although the relevance of studies that attempt to robustly gather information on variables that could enhance employees’ well-being cannot be neglected, the empirical examination and hypothesis testing of potential mitigators could be useful for both theory and practice. To assist in achieving this goal, the present study investigates the associations between work support, Satisfaction with Life, and perceived stress among automotive industry employees. Building upon past research, we predicted that higher levels of Work Support would exert an indirect link on the relationship between Perceived Stress and Satisfaction with Life [

9,

10].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants, Procedures, and Design

This is a cross-sectional study carried out with workers within the car industry. Data were collected in one automotive-parts factory located in Portugal. After contacting multiple companies by email using public listings (e.g., InfoEmpresas) during the first semester of 2023, one factory agreed to participate. Recruitment took place in June 2023. Participation occurred during work time, with tablets provided by management to facilitate completion. The survey was hosted on Qualtrics, responses were anonymous, and no IP or identifying data were stored. Before starting the questionnaire, each participant had access to the informed consent form, which outlined this study’s objectives and ensured the confidentiality and anonymity of all responses. Participants were required to be employees of the participating automotive parts factory at the time of data collection, aged 18 years or older, with a minimum tenure of six months to ensure adequate familiarity with the work environment and organizational practices. Only individuals with sufficient proficiency in Portuguese to complete the questionnaire were included. Temporary agency workers or interns with less than six months of employment, employees on extended leave (e.g., medical, parental, or unpaid leave) during the data collection period, and those who submitted incomplete or invalid questionnaires (e.g., missing more than 20% of responses or failing attention check items) were excluded from this study. We used a non-probabilistic convenience sample via corporate gatekeeper at the participating site. All eligible employees were invited.

We estimated the sample size a priori in G*Power 3.1 [

15]. considering a medium effect (f

2 = 0.15), α = 0.05, power of 0.95, one tested predictor, and two predictors in total. The result indicated the need for at least 89 participants.

The study sample comprised 672 participants. Regarding age, the largest age group was 30 to 39 years, representing 33.48% (

n = 225) of the participants. This was followed by the 40 to 49 years age group (29.46%,

n = 198) and the 20 to 29 years age group (27.23%,

n = 183). Older age groups, specifically 50 to 59 years and 60 years or more, constituted smaller proportions of the sample (8.33%,

n = 56 and 0.45%,

n = 3, respectively), while the youngest group, up to 19 years, was 1.04% (

n = 7). In terms of gender, the sample was marked by female individuals (52.98%;

n = 356).

Table 1 shows the sociodemographic detailed.

2.2. Measures

Survey of Perceived Organizational Support (SPOS), developed by Eisenberger et al., is a widely used instrument for assessing workers’ perceptions of the support offered by the organization [

16]. Based on social exchange theory, the SPOS measures the extent to which employees believe that the organization values their contributions and cares about their well-being. For this study, the shortened version validated for Portugal by Santos and Gonçalves (2010) [

17] was used. The items are rated on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Psychometric studies show that the SPOS has high internal consistency and predictive validity, making it a suitable instrument for investigating organizational commitment, work engagement, and employee well-being. Our industrial sample presented a unidimensional structure, with good fit after two theoretically justified residual covariances between the errors of items 2–3 and 6–8, CFI = 0.995, TLI = 0.992, RMSEA = 0.096, SRMR = 0.042, surpassing the two-factor alternative previously reported in Portugal. Reliability was high (McDonald’s ω = 0.914; α = 0.90; AVE = 0.571).

The Perceived Stress Scale (PSS, short version): It is one of the most used self-report instruments for measuring global stress. The scale aimed to measure whether respondents perceived ordinary life events with stress because of their uncertain, uncontrollable, or overwhelming nature. The scale is composed of 10 items using a 5-point Likert scale (0—never; 1—almost never; 2—sometimes; 3—often; and 4—very often). The validated Portuguese version, as adapted by Trigo et al. [

18], was used for the current study. The national validation study identified a unifactorial structure and reported good internal consistency (α = 0.87). In the present sample, the PSS-10 also showed adequate internal consistency (McDonald’s ω = 0.87; α = 0.87).

The Personal Wellbeing Index. Developed by the International Well-being Group and adapted to Portugal by Pais-Ribeiro and Cummins [

19]. Satisfaction with Life has been assessed through several domains. Seven items correspond to seven different domains of satisfaction: standard of living; health; personal achievements, personal relationship; sense of safety; community connectedness; and future security. These items aim at providing an explanation for an individual’s overall Satisfaction with Life, which one would suggest is captured by a single item of “general Satisfaction with Life”. The respondents rate their satisfaction in each domain on a scale from 0 (extremely dissatisfied) to 10 (extremely satisfied) for each domain, with a midway neutral point. The calculation of the total scores averaged the responses, ranging from 0 to 10, which represents the maximum possible score on the scale. The validation study in Portugal indicated a unifactorial structure with adequate internal consistency (α = 0.81; CFI = 0.90; RMSEA = 0.09). In the present sample, the scale also showed good internal consistency (McDonald’s ω = 0.87; α = 0.87).

Sociodemographic questionnaire: the sociodemographic questionnaire was used to characterize the sample in this study and provided information such as gender, age, schooling (educational level), job tenure (years), occupation/profession, job function, contract type, work schedule/shift, department, and absenteeism (self-reported days in the last 12 months).

2.3. Ethical Aspects

This study received approval from Ethics Committee for Research in Social Sciences and Humanities at the University of Minho (approval number: CEICSH 012/2023 on 6 March 2023)). All participants provided informed consent prior to their involvement, following the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and adhering to applicable national regulations governing research with human participants.

2.4. Data Analysis

Analyses were conducted to examine the indirect and direct effects of Satisfaction with Life on Perceived Stress through Work Support. The analysis of the indirect and direct effects employed bootstrapping with 10,000 resamples and percentile-based confidence intervals, with an alpha level set at 0.05. Prior to running these analyses, the assumptions underpinning the regression models were assessed. The assumption of normality for the model residuals was evaluated using several methods. Initially, the quantiles of the model residuals were plotted against the quantiles of a Chi-square distribution, commonly referred to as a Q-Q scatterplot, combined with the Shapiro–Wilk test. The results of this test were not statistically significant (W = 1.00, p = 0.077). The presence of multicollinearity between the predictors in the model was assessed by calculating Variance Inflation Factors (VIFs). High VIF values can indicate an increased effect of multicollinearity, which might compromise the stability and interpretation of regression coefficients. According to established guidelines, VIFs greater than 5 warrant concern. In this analysis, all predictors in the regression model demonstrated VIFs considerably below this threshold, suggesting no issue with multicollinearity. Specifically, the VIF for Satisfaction with Life was 1.25, and the VIF for Work Support was 1.25. Influential data points, or outliers, were identified by analyzing Studentized residuals. The analysis did not report any observations exceeding established thresholds. Analyses were conducted in Jasp (version 0.9.1) and Jamovi (version 2.6.44).

3. Results

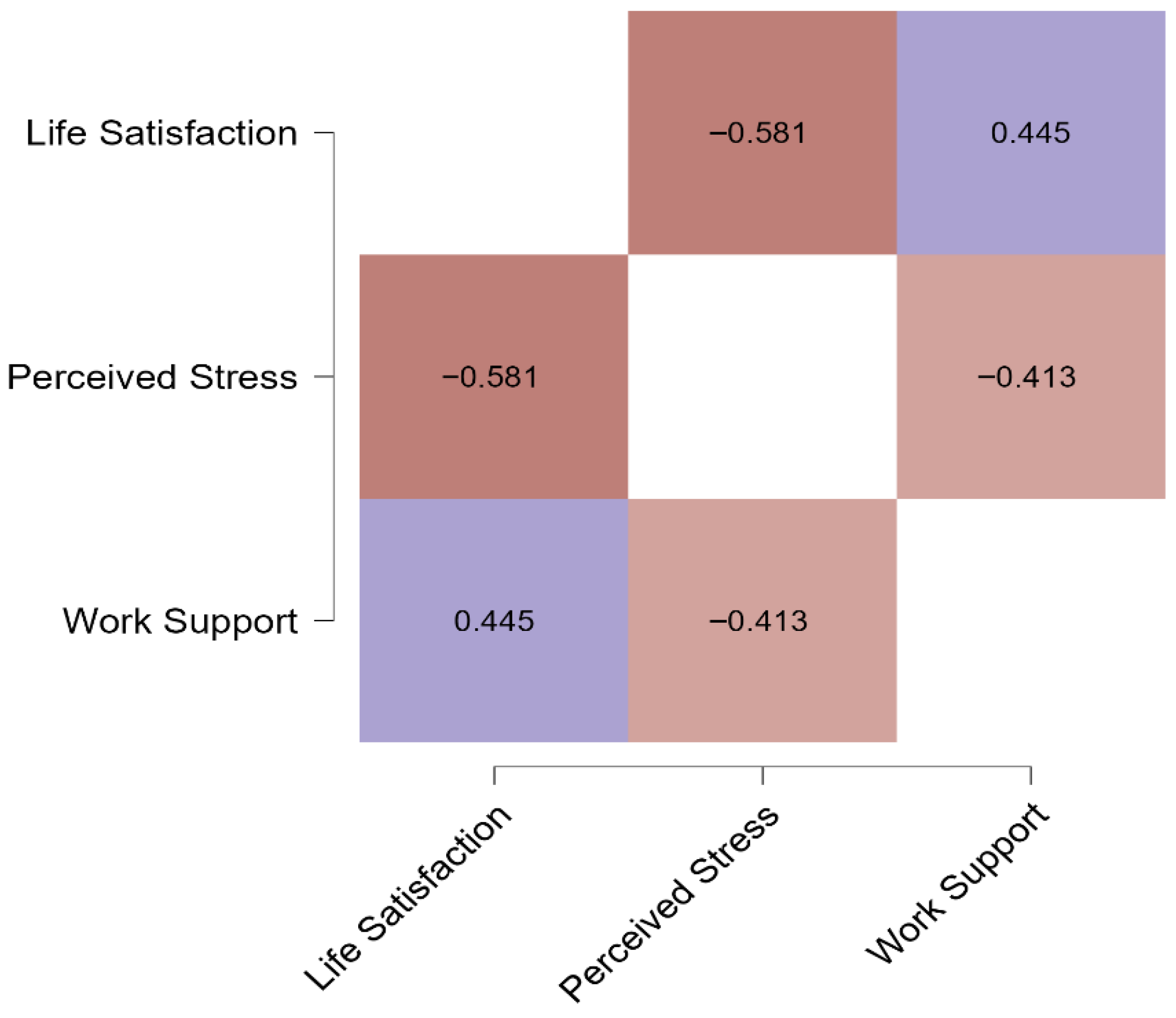

The results of the statistical analyses are presented in this section, beginning with bivariate correlations between key study variables and concluding with the findings from the analysis of indirect effects. Pearson’s correlations with Holm correction were calculated to examine the relationships between Work Support, Satisfaction with Life, and Perceived Stress (

Figure 1). Significant correlations were found, namely a positive and moderate correlation between Work Support and Satisfaction with Life (r = 0.445,

p < 0.001) and a negative and moderate correlation between Work Support and Perceived Stress (r = −0.413,

p < 0.001). Furthermore, a significant, a negative and moderate correlation was observed between Satisfaction with Life and Perceived Stress (r = −0.581,

p < 0.001).

Significant findings emerged from analyses of both direct and indirect effects. The average direct effect of Satisfaction with Life on Perceived Stress was statistically significant (B = −0.210, 95% CI [−0.245, −0.177],

p < 0.001). This indicates that, even after accounting for the influence of Work Support, Satisfaction with Life continues to exert a negative impact on Perceived Stress.

Table 2 summarizes the decomposition of effects. The indirect effect of Satisfaction with Life on Perceived Stress through Work Support was statistically significant, albeit small in size (B = −0.036, SE = 0.008, 95% CI [−0.051, −0.020],

p < 0.001), indicating that Work Support partially accounted for this relationship. The total effect (B = −0.246, SE = 0.014, 95% CI [−0.276, −0.218],

p < 0.001) reflects the combined influence of direct and indirect pathways.

Subsequent analyses were conducted to estimate a reversed indirect model, taking Work Support as a predictor.

To better understand the mechanisms,

Table 3 presents the individual path coefficients. Satisfaction with Life positively predicted Work Support (a = 0.343, SE = 0.030, 95% CI [0.286, 0.401],

p < 0.001), and Work Support was negatively associated with Perceived Stress (b = −0.105, SE = 0.021, 95% CI [−0.146, −0.060],

p < 0.001). Taken together, these estimates suggest that Work Support had a significant indirect effect on the links between Satisfaction with Life and Perceived Stress, even though the direct path from Satisfaction with Life to Perceived Stress remained strong.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to examine the relationship between Satisfaction with Life, Work Support and Perceived Stress among workers in the motor vehicle sector. Importantly, we further tested the applicability of Work Support as a variable exerting indirect effects between Satisfaction with Life and Perceived Stress. To the best of our knowledge, such analyses have not been explored in the Portuguese context so far.

The cross-sectional findings suggest that employees who see more Work Support have higher job satisfaction and reduced stress, and that job satisfaction itself is highly interrelated with stress experience. In addition, the findings suggest that part of this is indirectly affected by Work Support, thus highlighting the interdependence of personal welfare and work resources in influencing employees’ stress outcomes.

4.1. Work Support and Satisfaction with Life

Our cross-sectional findings suggest that employees who feel supported at work tend to be more satisfied with their lives. However, when examining the correlation between the two constructs, it must be emphasized that this depiction is not causal and must be interpreted as preliminary. Despite this, results are in line with recent evidence showing that supportive relationships in the workplace not only improve well-being but also help reduce stress, partly because they strengthen the sense of belonging to the team and the organization, and act as a buffer against everyday pressures [

11]. The spillover theory helps explain this link by proposing that what happens in the work domain often spills over to influence how people feel in other areas of life [

5]. The Conservation of Resources theory offers another perspective. According to Hobfoll [

20], people are motivated to seek out, protect, and grow valuable resources. Supportive colleagues and supervisors are among the most important of these resources, because they help employees conserve energy, manage challenges, and maintain a positive outlook.

Zhai et al. [

21] have shown that work support promotes “thriving at work,” a state characterized by both vitality and learning, which acts as an intermediary process linking workplace resources to overall Satisfaction with Life. Supportive work environments foster trust, cooperation and a sense of belonging, all of which contribute to more positive spillover from the work domain into life outside of work. In the Portuguese automotive industry, where employees frequently face tight production targets, repetitive tasks and physical strain, these mechanisms may be especially important, as the availability of practical and emotional support can help workers sustain their overall well-being despite the pressures inherent to the job.

In environments like the Portuguese automotive industry, where production targets are demanding and the work can be both repetitive and physically taxing, these resources may be even more critical. Having supervisors and peers who are willing to listen, help with problem-solving, and provide emotional reassurance can make it easier to manage work demands and prevent them from spilling over negatively into personal life. This kind of support can also help reduce work–family conflict [

22] making it easier for employees to maintain a healthier balance between professional and personal well-being.

4.2. Work Support and Perceived Stress

The results of this study suggest that employees who perceive higher levels of support in the workplace tend to experience lower levels of stress, although no causal links could be established from this research cross-sectional design. This finding aligns with the stress-buffering hypothesis, which proposes that social support can protect individuals from the harmful effects of stressors [

23]. Recent research has reinforced this view. For instance, Acoba found that perceived social support significantly reduces perceived stress, partly by influencing how individuals appraise and respond to stressful events, which in turn enhances positive affect and lowers symptoms of anxiety and depression [

24]. Similarly, Gillman et al. observed that strong social identification with colleagues, combined with workplace support, is linked to lower perceived stress and higher Satisfaction with Life, suggesting that both emotional and identity-based connections at work can mitigate stress responses [

11].

However, while workplace support emerged as a significant factor in stress reduction, its contribution explains only part of the variation in perceived stress. This points to the influence of other elements, such as workload, job control, and external life stressors, in shaping employees’ stress experiences. As highlighted by Berglund et al. (2025), the protective effect of social support may weaken under intense or chronic stress conditions, underscoring the importance of tailoring support strategies to the specific pressures employees face [

25].

4.3. Satisfaction with Life and Perceived Stress

The negative association between Satisfaction with Life and Perceived Stress observed in this study is well aligned with existing evidence showing that individuals who are more satisfied with their lives tend to perceive lower levels of stress. Recent studies indicate that Satisfaction with Life can function as a psychological resource, improving emotional regulation and fostering more adaptive coping strategies, which in turn reduce stress perceptions [

26]. Padmanabhanunni et al. further suggest that Satisfaction with Life may operate on the impact of stress on mental health outcomes, acting as a buffer against symptoms such as anxiety and hopelessness [

27].

The transactional model of stress helps explain this link, proposing that how individuals appraise potentially stressful situations depends on their available resources, including stable emotional and cognitive resources associated with greater Satisfaction with Life [

28]. There is also evidence of a reciprocal dynamic, where higher Satisfaction with Life reduces stress exposure and reactivity, while lower stress facilitates a more positive evaluation of life circumstances [

29]. In the context of our findings, this suggests that Satisfaction with Life may not only reflect general well-being but may also enhance the capacity to mobilize and benefit from workplace resources such as social support.

4.4. Indirect Effect of Work Support

The results of this study suggest that Work Support exerted an indirect effect in the association between Satisfaction with Life and Perceived Stress, indicating that part of the beneficial effect of Satisfaction with Life on stress operates through the availability of supportive relationships in the workplace. Recent evidence supports this mechanism. For example, Hu et al. [

30] found that perceived social support showed indirect effects on the relationship between stress and Satisfaction with Life among college students during the COVID-19 pandemic, underscoring its role in buffering stress and enhancing well-being. Similarly, Wang et al. reported that family and friend support also indirectly affected the link between parenting stress and Satisfaction with Life, suggesting that support resources are instrumental across diverse contexts [

31].

From the perspective of the Conservation of Resources theory [

20,

32], social support represents a resource that individuals can invest to protect against resource loss, such as emotional energy, caused by stressors, while also enabling the accumulation of additional resources, like positive affect and resilience. In workplace contexts, individuals with higher Satisfaction with Life may be more proactive in cultivating and maintaining supportive relationships, which in turn help mitigate the negative impact of stress [

21].

The fact that the analysis of indirect effect was partial indicates that other mechanisms may also explain how Satisfaction with Life relates with stress, which warrants additional examinations. These may include enhanced coping strategies, adaptive cognitive appraisals, or higher resilience, all of which are linked to greater overall well-being. Future research could explore these pathways to develop a more comprehensive model of how personal and workplace resources jointly shape stress outcomes.

4.5. Implications

The present findings contribute to a deeper theoretical understanding of how Work Support and Satisfaction with Life might jointly influence stress outcomes, underscoring the value of integrating perspectives from occupational health psychology and positive psychology. The recent literature highlights that a comprehensive approach to workplace well-being requires not only the prevention of harm but also the active promotion of positive psychological resources, such as trust, engagement, and resilience, to foster thriving environments [

33]. Positive psychology interventions, for instance, have been shown to improve satisfaction, strengthen social bonds, and reduce strain, which aligns with our findings that Satisfaction with Life can enhance the perception of supportive resources at work [

34].

This integrated lens also challenges traditional occupational stress models like the Job Demands-Resources framework, which often center on job characteristics as primary stress drivers. Our results indicate that broader life circumstances, particularly overall Satisfaction with Life, can shape the way employees perceive and benefit from workplace resources. This supports the resource investment principle of the Conservation of Resources theory, which proposes that individuals with more initial resources, such as strong well-being, are better equipped to acquire additional resources and prevent losses [

20].

From a practical standpoint, these insights could encourage organizations to adopt strategies that not only improve job design and reduce demands but also bolster employees’ Satisfaction with Life outside work, for example, through flexible policies, community engagement, and personal development programs. Evidence shows that such approaches create the conditions for sustained support networks at work, which in turn help with stress management and in maintaining performance over time [

35].

4.6. Limitations and Future Directions

This study offers useful insights into the connections between Work Support, Satisfaction with Life, and Perceived Stress, but several limitations need to be recognized. The cross-sectional design means that conclusions about cause are impossible to estimate. The model of direct and indirect effects suggests a directional relationship from Satisfaction with Life to Work Support and then to Perceived Stress, but other causal sequences remain possible. Cross-sectional analyses of indirect effect can yield biased estimates, in contrast to longitudinal study designs [

36].

Moreover, this study defined Work Support as a single concept, potentially masking the varying impacts of different support sources, such as supervisors, coworkers, and the organization itself, which could have different effects on employee outcomes [

10]. The indirect effect of Work Support on the relationship between Satisfaction with Life and Perceived Stress was statistically significant, yet its size was relatively modest (B = −0.036). The results suggest that additional indirect factors are probably present, but they were not accounted for in this investigation. This study nonetheless reveals several promising areas for future research, including the necessity for longitudinal studies in order to establish the temporal sequence of relationships between Satisfaction with Life, Work Support, and Perceived Stress. Collecting data from multiple sources is also crucial, as researchers should gather data from various sources to decrease common method bias. Supervisor ratings of support provision could be compared with employee perceptions, while objective stress indicators could also complement self-reported measures. Industry-specific investigations could also enhance the value of our results. Studies could then compare observed relationships across various industries and occupations [

37].