1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted family life globally, intensifying economic hardship, social isolation, and psychological distress (

Congressional Research Service, 2022). In the Caribbean, where mental health services are often limited, these challenges were especially acute (

Seon et al., 2023). Yet amid these difficulties, artmaking, a long-standing cultural practice in the region, remained a vital source of comfort and resilience (

Dorchin, 2017). Art served not only as a medium for creative expression but also as a therapeutic outlet to process emotions and sustain familial bonds during times of upheaval.

While the healing potential of the visual arts is documented for families (

Chilton et al., 2024;

Gao et al., 2022;

Sabados, 2024;

Teunissen et al., 2025;

Yang et al., 2023), there remains a gap in understanding how Caribbean families specifically utilized creative practices to navigate the pandemic. Bridging this gap is critical for understanding how art illuminates and supports resilience and emotional well-being in underrepresented, resource-limited communities, an area that remains underexplored in family resilience research more broadly.

The study investigates how Caribbean families used visual art to represent resilience before and after the onset of COVID-19 pandemic. With Caribbean populations historically underrepresented in resilience research (

Walker et al., 2022), this study offers a culturally specific and timely contribution. The inquiry is guided by two core objectives: (1) to explore how families visually depict resilience across different phases of the pandemic and (2) to analyze how these expressions reflect adaptive and coping processes within a family systems framework. The central research question asks: How do Caribbean families visually represent resilience and emotional coping before and after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic?

1.1. Family Disruption and Adaptation in COVID-19

The pandemic introduced widespread disruptions to family life, exposing families to multiple, and often simultaneous, stressors. Heightened caregiving demands, isolation, and health anxieties coexisted with moments of unexpected bonding and strengthened routines, illustrating the duality of strain and growth during crises (

Lucia La Rosa et al., 2024;

McLoone et al., 2022).

International studies in countries such as Australia and Italy reveal that, even amid diminished quality of life and cohesion, many families adapted by enhancing communication and problem-solving strategies (

McLoone et al., 2022). These findings underscore that resilience encompasses more than endurance; it involves the reorganization of roles and systems in response to changing circumstances.

However, this adaptive capacity was not experienced equally. Sociodemographic factors, including race, gender, and income, significantly influenced how families coped with pandemic stressors. Marginalized families faced compounded pressures: financial insecurity, limited access to care, and greater psychological strain (

Andrade et al., 2022;

Vélez-Grau et al., 2024). For example, Latinx families experienced intensified grief, deteriorating adolescent mental health, and elevated parental stress (

Vélez-Grau et al., 2024).

Gender roles also shaped how caregiving was distributed within households. While some fathers increased involvement during the pandemic, studies show that these shifts were often superficial and temporary. Structural gender norms continued to assign greater caregiving responsibility to women, even at the cost of their professional aspirations (

Rinaldo & Whalen, 2023). These dynamics highlight the uneven burden of adaptation and the need for more equitable structural support.

1.2. Resilience as a Multisystem Process

Resilience is increasingly recognized as a dynamic process that unfolds across individual, familial, and societal systems. Emotional regulation, stability of routines, and meaning-making emerged as central mechanisms for resilience during COVID-19 (

Carpenter et al., 2022). For marginalized families, in particular, meaning-making offered a powerful tool to reframe adversity and cultivate growth.

Masten and Motti-Stefanidi (

2020) describe the pandemic as a multisystem disaster, disrupting schools, healthcare, and social supports, thereby threatening child and family well-being. In this context, resilience depends on interdependent systems: children on families, families on communities, and communities on institutions.

Research by

Ungar et al. (

2021) and

Van Breda (

2018) supports this view by emphasizing the role of strong family relationships, open communication, and extended caregiving networks in promoting emotional stability. These relational and cultural dimensions are particularly relevant in the Caribbean, where resilience often emerges from collective, not individual, strength.

1.3. Caribbean Family Resilience

Caribbean families have historically demonstrated an impressive capacity for resilience amid economic instability, frequent natural disasters, and limited healthcare infrastructure (

Power et al., 2015;

Wilkinson et al., 2016). This strength is rooted in expansive kinship networks, cultural traditions, and spiritual practices.

Unlike Western nuclear family models, Caribbean households are often multigenerational and communal. Women frequently assume central roles in both childrearing and economic provision, supported by extended relatives and close friends regarded as kin (

Donald & Brock, 2023;

Mohammed, 2002). These fluid and adaptive structures facilitate shared caregiving, emotional support, and resource pooling, particularly during crises (

Navara & Lollis, 2009). Consequently, resilience within Caribbean families is not solely an individual or nuclear family process but a community-oriented one, reflecting culturally specific pathways of coping and adaptation.

Spirituality and cultural rituals further strengthen these networks. Faith-based practices, ranging from prayer to interfaith ceremonies, offer emotional grounding and foster community cohesion (

CARICOM, 2023). These traditions provide a collective framework for navigating uncertainty, imbuing families with a sense of hope and purpose.

Artistic expressions and storytelling also play an essential role. Oral traditions have long helped Caribbean families transmit values and process trauma (

Lowery, 2013). Contemporary research affirms that visual and verbal storytelling enhances resilience by connecting individuals to their cultural heritage and family identity (

Donald & Brock, 2023).

Nature-based practices round out this ecosystem of resilience. Families often turn to natural environments, beaches, forests, and gardens for emotional restoration. When access to such spaces is limited, they adapt by engaging in gardening or creating nature-inspired art, illustrating how ecological connectedness supports spiritual and emotional healing (

Donald & Brock, 2023).

Interestingly, economic hardship can also foster resilience. Families with fewer resources often rely more heavily on communal support and adaptive strategies, challenging the assumption that higher income equals greater resilience (

Donald & Brock, 2023).

1.4. Nature and Family Resilience

Building on these cultural frameworks, nature emerges as a critical yet often underexplored component of family resilience in the Caribbean. More than a passive backdrop, nature actively contributes to emotional regulation, social bonding, and spiritual well-being (

Donald & Brock, 2023).

The Nature-Based Biopsychosocial Resilience Theory (

White et al., 2023) provides a useful framework for understanding these effects. It posits that nature enhances resilience across physiological (e.g., reduced stress), psychological (e.g., emotional clarity), and social (e.g., family connection) domains. Empirical studies support this theory.

Jimenez et al. (

2021) found that access to green space improves emotional regulation, sleep, and social cohesion, factors that support healthy family functioning. Similarly,

Kuo (

2015) identified over 20 mechanisms through which nature contributes to mental and physical health.

Evidence from programs like South Africa’s Kinship Programme further demonstrates that shared nature experiences can strengthen parent–child relationships and foster emotional healing (

Duff et al., 2024). These findings affirm that ecological connection is not peripheral but central to family resilience, especially in culturally grounded communities.

1.5. Artmaking and COVID-19

Alongside ecological coping, artmaking has served as a transformative resilience tool during the pandemic. Situated within the broader discourse of multisystemic resilience, creative expression operates across emotional, cognitive, and cultural domains. Studies confirm that artistic engagement, whether through active creation or appreciation, helps regulate emotion, process trauma, and cultivate psychological stability (

Chmiel et al., 2022;

Fancourt et al., 2019). Theories such as

Siegel’s (

2010) intrapersonal attunement and

Csíkszentmihályi’s (

1990,

1996) flow further support the idea that art fosters coherence and emotional control during stress.

At the family level, collaborative art projects mirror adaptive shifts in household dynamics. These practices function as symbolic rituals that reinforce unity, echoing the communal and spiritual foundations of Caribbean family life (

Fraenkel & Cho, 2020). Formal art therapy interventions, such as directed drawing or mandala-making, have proven especially helpful for children in navigating grief and anxiety (

Le Vu et al., 2022). These structured practices offer nonverbal modes of healing that complement traditional mental health support. Integrating these insights, artmaking aligns with the multisystem resilience framework (

Masten & Motti-Stefanidi, 2020), affirming that adaptive recovery must span individual, familial, and cultural dimensions.

1.6. Family Resilience Process Theory

To synthesize the aforementioned ideas from the literature, the family resilience process theory (

Walsh, 2016) is used as the primary theory for the study. It offers a comprehensive lens for understanding how families confront adversity through shared strengths. Rather than emphasizing individual traits, this theory highlights how families collectively adapt through three interrelated pillars, belief systems, organizational patterns, and communication processes, that enable families to adapt in the face of crisis. Within these pillars, belief systems consist of meaning-making, positive outlook, and transcendence or spirituality, which help families interpret adversity within broader moral, cultural, and/or spiritual narratives. Communication processes involve emotional sharing, clarity, and collaborative problem solving, which foster trust and creativity in navigating stress. Organizational patterns emphasize flexibility, connectedness, and the mobilization of social and economic resources that enable families to sustain functioning and cohesion in the midst of challenges.

In the context of COVID-19,

Walsh (

2020) describes families as navigating both acute loss and chronic stress. Many relied on meaning-making, spiritual connection, and collective hope to maintain coherence and psychological stability. Everyday practices, such as creating a home shrine to honor deceased loved ones, exemplify how personal rituals can support communal healing and affirm resilience.

Within this framework, several processes are especially pertinent to the present study’s focus on Caribbean family artmaking before and during the pandemic. Meaning-making allows families to reinterpret grief and disruption through culturally rooted visual narratives that reflect shared values of endurance and kinship (

Carpenter et al., 2022;

Walsh, 2020). Hope functions as a sustaining force that nurtures optimism and emotional persistence in the face of uncertainty. Transcendence, often expressed through spiritual or artistic practices, enables families to symbolically rise above challenges and envision healing. Finally, collaborative problem solving, a form of creative adaptability (

Walsh, 2021), presents in collective artmaking where families co-create images of stability, continuity, and transformation.

These insights align directly with the goals of the present study, which seek to understand how Caribbean families visually represent resilience and emotional coping before and during the pandemic. The theory provides a valuable interpretive framework for analyzing the visual artwork created by families that highlight how artistic expression serves not only as a coping mechanism but also as a vehicle for constructing shared meaning, preserving hope, and embodying transcendent values during crisis.

2. Materials and Methods

This study employed an arts-based research (ABR) methodology to explore the central research question: How do Caribbean families visually represent resilience and emotional coping before and after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic? ABR integrates creative processes and artistic media, such as visual arts, performance, and narrative, into the research process to explore complex human experiences and emotional realities (

Leavy, 2020). Diverging from traditional, text-centered approaches, ABR privileges sensory, affective, and symbolic forms of expression, providing a means to engage with embodied and nonverbal dimensions of meaning (

Tian, 2023).

This methodology was particularly suited for engaging Caribbean families whose cultural expressions often emphasize visual storytelling, collective creativity, and spiritual symbolism. ABR enabled researchers to access layered and culturally grounded representations of resilience, fostering deeper insight into families’ lived experiences of stress, coping, and adaptation. The approach also aligned with critical and emancipatory research aims, challenging dominant discourses and amplifying marginalized voices (

Baart & Roos, 2022;

Straka, 2019).

2.1. Participants and Sampling

Participants included 25 English-speaking Caribbean families from Trinidad, Jamaica, and Grenada, recruited as part of a broader study on resources that support Caribbean family resilience. The rationale for focusing on English-speaking Caribbean families was due to the researchers’ accessibility and linguistic consistency of data. Recruitment occurred through gatekeepers, who were individuals known to the researcher and identified eligible and willing families, direct researcher engagement during participant observation, and snowball sampling. Thirteen families contributed data prior to the pandemic (November 2019–March 2020), and thirteen participated after the onset of COVID-19 (March 2020–July 2022). One family participated before the pandemic and after the onset. Families varied in composition (e.g., nuclear, extended, single-parent) and socioeconomic status. Eligibility required that all family members be born in the Caribbean and currently reside in an English-speaking Caribbean nation (

Table 1).

2.2. Data Collection

Data were drawn from de-identified visual artworks and accompanying descriptions created by participating families. The study received approval from the Institutional Review Board at Florida State University on 11 May 2023, with approval code STUDY00003034. All participants provided informed consent. Identifying details were removed from all data prior to analysis to ensure confidentiality and cultural sensitivity. The COVID-19 pandemic coincided with the ongoing research timeline, allowing for a natural comparison of pre- and post-pandemic experiences. Each participating family was invited to create a collective artwork representing their shared emotional and relational experiences in response to the most stressful situation that they had experienced together as a family, using a range of materials (e.g., 18 × 24-inch paper, markers, colored pencils, watercolor paints, clay, and natural objects). The level of participation varied: some families collaborated as a unit, others delegated artwork to one or two members, while a few had one member create art reflecting broader family narratives.

Families were encouraged, but not required, to discuss and describe their creations, providing interpretive context. These descriptions, where available, were recorded and transcribed as part of the qualitative data.

2.3. Analysis

The data analysis process for this study was iterative and collaborative, involving multiple stages of engagement and interpretation. The coding team comprised the authors, along with two trained undergraduate research assistants. All members underwent analysis training to ensure consistency in approach and familiarity with the methodology. A key component of this training included reflective artmaking (

Gerber et al., 2018), a process in which researchers created their own visual responses to the participants’ artworks. This approach fostered deeper emotional engagement with the data and supported a more empathetic and embodied understanding of the families’ visual narratives.

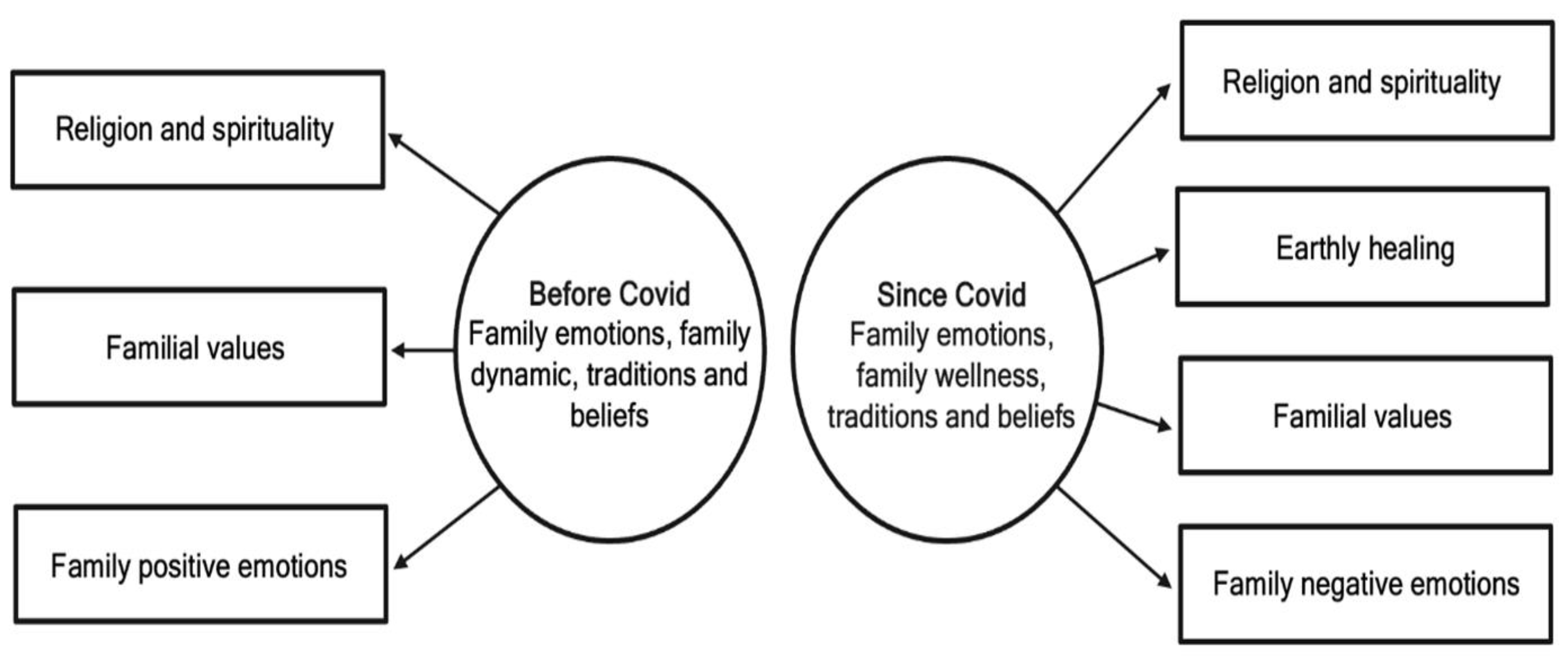

The analysis unfolded in three primary phases, examining both families’ completed artworks and their accompanying descriptions. In the first phase, initial coding and interpretation, the team employed open coding techniques, drawing from both visual and textual data. The team identified recurring motifs, color schemes, compositional elements, and themes embedded in the families’ artworks and their accompanying descriptions. Collaborative discussions were held regularly to resolve interpretive differences and refine the codebook, ensuring a shared language and approach across coders with the first author making final decisions when discrepancies occurred. When discrepancies arose, the first author made final determinations to ensure analytic consistency.

The second phase, thematic development, involved revisiting and revising the initial codes. Codes were renamed and grouped into broader conceptual categories that captured the complexity of family resilience before and during the pandemic. This stage included ongoing peer debriefing and memo-writing, which allowed the team to document emerging insights and critically reflect on the evolving coding framework. Special attention was paid to shifts in visual symbols and narrative emphasis across the pre- and post-pandemic timepoints.

In the third phase, trustworthiness and member reflections, preliminary themes were shared with three participating families who had consented to be contacted for follow-up if needed. These families reviewed the researchers’ interpretations and offered feedback that led to the renaming, affirmation, or refinement of several codes. Although reflections were obtained from only three families, they were the only participants who had agreed to be contacted. Their insights contributed meaningfully to the credibility of the researchers’ interpretations.

Throughout the analysis, the research team employed strategies to ensure methodological rigor, including analysts’ triangulation, peer debriefing, and participant member checks (completed by the first author in collaboration with the three families). These practices reinforced the credibility and depth of the study’s conclusions.

4. Discussion

This study examined how Caribbean families visually represent resilience and emotional coping before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, using an arts-based research methodology. In doing so, it expands the existing frameworks of family resilience by centering cultural specificity, emotional duality, and visual storytelling. The findings intersect

Walsh’s (

2020) family resilience theory and emerging theory on nature-based healing (

White et al., 2023) while challenging overly linear and individualistic models of coping.

Much of the existing literature on family stress and resilience has been developed within Western cultural contexts, emphasizing nuclear family structures, individual agency, and psychological regulation as primary markers of resilience (

Masten & Motti-Stefanidi, 2020;

Walsh, 2016). These frameworks often overlook the communal, spiritual, and historically grounded dimensions of resilience that characterize Caribbean family life. For instance, models that equate resilience with emotional positivity or rapid recovery may fail to recognize how Caribbean families navigate adversity through collective endurance, cyclical adaptation, and expressive creativity rather than through linear recovery or emotional suppression.

Caribbean families have long developed coping mechanisms shaped by histories of colonization, migration, and economic instability; contexts that demand flexible kinship systems, shared caregiving, and intergenerational solidarity (

Donald & Brock, 2023;

Mohammed, 2002). As such, resilience within these families is not merely a response to stress but a culturally embedded mode of survival and meaning-making. Existing theories often treat culture as a moderating variable, whereas in Caribbean contexts, culture functions as the very mechanism through which resilience is enacted (

Donald, 2025).

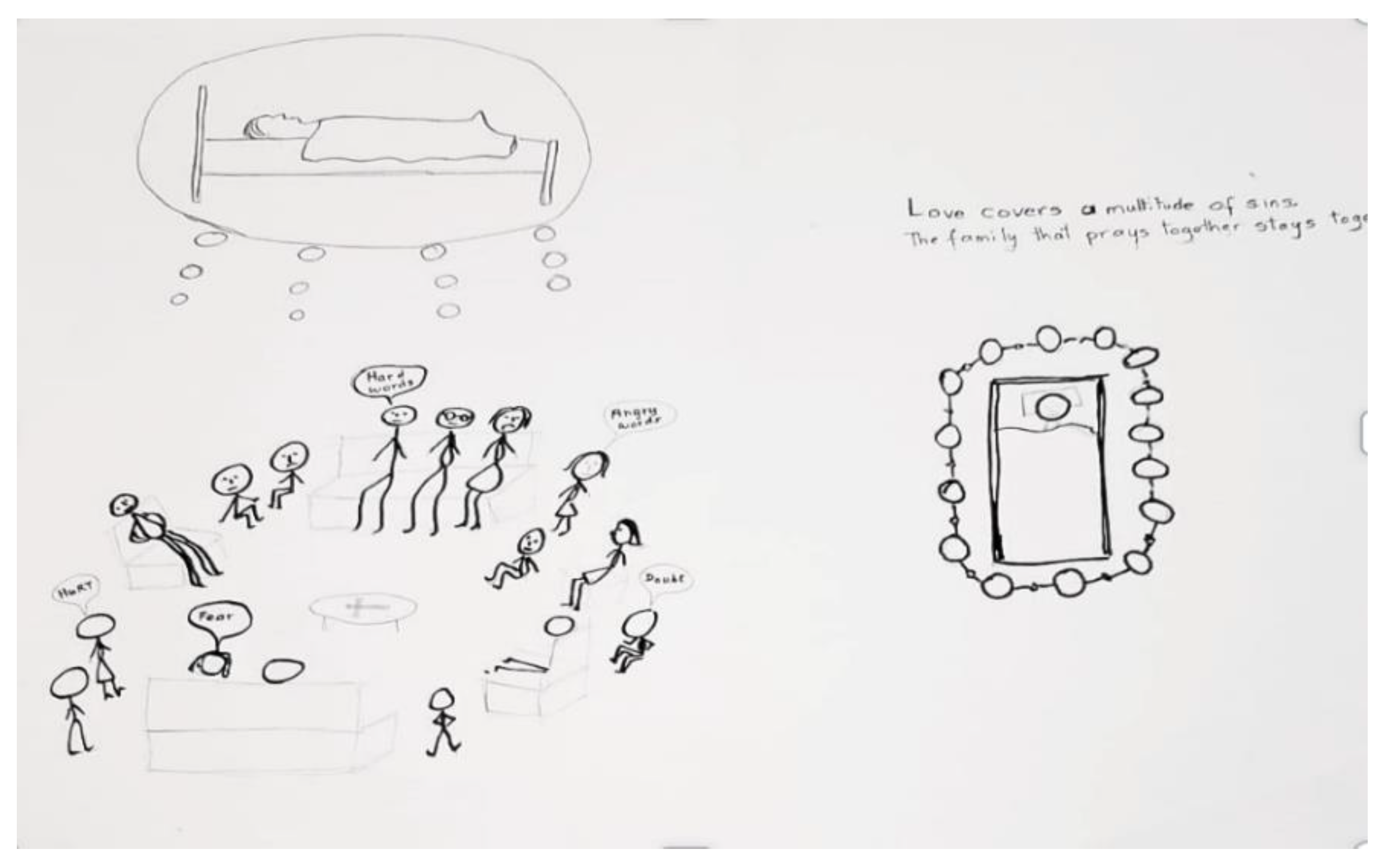

4.1. Emotional Transformation: A Dynamic and Systemic Process of Resilience

The findings of this study reinforce that resilience, as expressed by Caribbean families through visual art, is neither a fixed psychological trait nor an uncritical celebration of strength. Rather, it emerges as a dynamic, emotionally layered, and culturally situated process of adaptation. This conceptualization aligns with

Walsh’s (

2016,

2020) family resilience framework, which views resilience as a relational, nonlinear journey, shaped by meaning-making and collective coping strategies. In contrast to conventional models that emphasize individual emotional regulation or positive affect (

Masten & Motti-Stefanidi, 2020), the artistic depictions in this study reveal the coexistence of joy, anxiety, hope, and grief, challenging binary constructions of emotional experience.

The simultaneous presence of distress and optimism in the artwork underscores the emotional duality inherent in the resilience process. Families did not suppress difficult emotions but rather integrated them into visual narratives that reflected ongoing negotiations of meaning. This is consistent with

Ungar et al.’s (

2021) multisystemic resilience theory, which emphasizes the role of adaptive systems that enable individuals and families to engage with, rather than eliminate, emotional adversity. Post-pandemic artworks illustrated complex emotional experiences in which symbols of loss, uncertainty, and fear were juxtaposed with imagery of spiritual strength, familial closeness, and hope for renewal.

This emotional complexity is also reflected in

Carpenter et al.’s (

2022) emotional trajectory model, which describes families’ movement through stages of anxiety, adaptation, and reconstruction. Caribbean families’ artistic expressions mirrored this trajectory by visualizing resilience as a process of transformation, not recovery. Resilience was depicted not as a return to a previous state of normalcy but as an evolving state of being that is formed through the reconfiguration of values, reinterpretation of traditions, and reaffirmation of emotional bonds.

Importantly, these findings suggest that resilience, in this context, operates as a systemic and cultural process rather than a solely individual psychological outcome. The artworks reveal that emotional resilience is cultivated through shared belief systems, spiritual practices, and intergenerational connections, aligning with the systemic coping strategies emphasized in the literature on Caribbean family resilience (

Donald & Brock, 2023;

Navara & Lollis, 2009). Visual art served not only as a reflective medium but also as an active process of resilience building, enabling families to process trauma, celebrate survival, and construct shared meaning.

Recognizing this emotionally transformative dimension of resilience has practical implications for family scholarship and practice. It calls for the integration of culturally grounded, arts-based methodologies into family studies, mental health services, and community interventions. Such approaches can illuminate the lived emotional experiences of marginalized families and foster inclusive strategies for supporting resilience in culturally diverse contexts.

4.2. Reconfiguring Family Roles and Dynamics

The pandemic prompted significant shifts in family organization, reflected in visual representations of shared activities and cooperative roles. These shifts suggest strengthened familial bonds but also reveal enduring structural inequalities. While some artwork illustrated increased collaboration, the study did not find clear evidence that traditional gender roles were disrupted. It is therefore likely that women continued to bear disproportionate caregiving responsibilities, a pattern echoed in broader literature (

Andrade et al., 2022;

Rinaldo & Whalen, 2023).

One possible explanation for this discrepancy between existing literature and the visual data lies in the composition of participant families across the two collection periods. The family demographics were not identical pre- and post-COVID, with unequal representation of family types and household structures that may have influenced how gendered responsibilities were distributed and portrayed. For example, a higher number of single-parent or female-headed households in the post-COVID sample may have shaped the visual emphasis on resilience and togetherness rather than on shifting gender norms.

Another explanation may be cultural. Despite the documented stressors of the pandemic, gendered caregiving expectations among Caribbean families may have remained relatively stable. In many Caribbean contexts, caregiving and domestic responsibilities are embedded within cultural scripts of womanhood and kinship, which persist even amid crises. Thus, the absence of explicit depictions of changing gender roles in the artwork does not necessarily indicate a lack of adaptation but rather reflects the enduring cultural logic through which family resilience is expressed and maintained.

This dynamic illustrates that crises do not inherently lead to structural transformation. Rather, resilience may occur alongside the reinforcement of existing inequalities. The art captured this tension: solidarity and care were evident, but so too were the limitations of systemic change. These findings challenge assumptions that shared adversity produces equitable redistribution of labor and underscore the need for gender-sensitive family interventions in times of crisis.

4.3. Wellness as a Relational and Ecological Practice

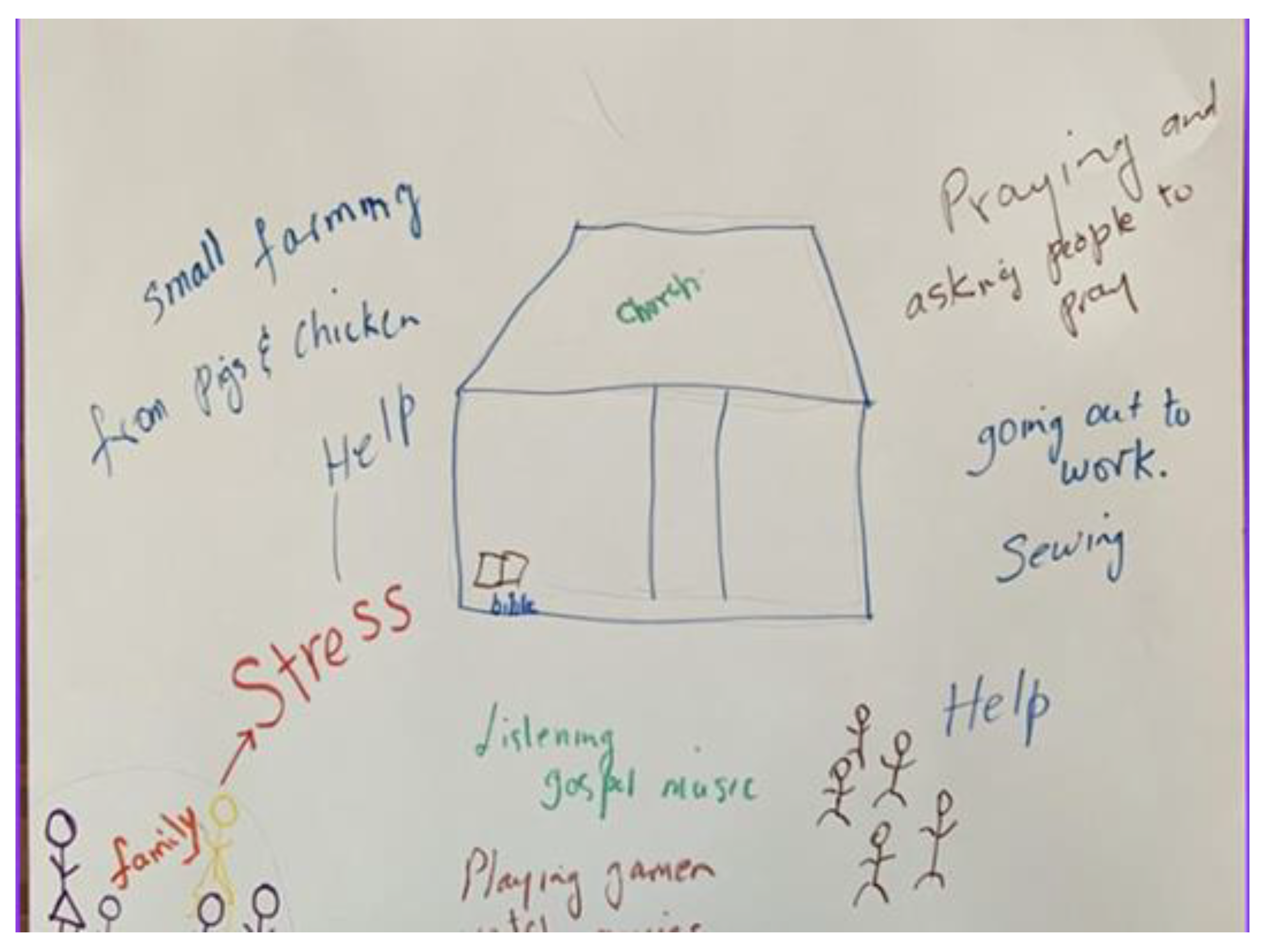

Family wellness transcended individual well-being and reflected a holistic, communal, and environmental approach. The presence of nature, spiritual imagery, and references to healing suggest that Caribbean families do not view wellness in isolation but as an interconnected experience. This aligns with literature on non-Western resilience frameworks, which emphasize community and ecological harmony over individual psychological coping (

Jimenez et al., 2021).

The shift toward reliance on nature for healing in post-pandemic artistic expressions suggests that families sought restoration not only through faith but also through engagement with nature, highlighting an expansion of coping strategies beyond traditional religious frameworks. This aligns with the Nature-Based Biopsychosocial Resilience Theory (

White et al., 2023), which posits that contact with nature can help individuals build and maintain biological, psychological, and social resilience-related resources, particularly in challenging times.

This finding broadens existing resilience research, as traditional literature on resilience often prioritizes psychological resilience while overlooking the role of natural and spiritual environments in coping with stress. The integration of faith and natural elements in artistic expressions suggests a more inclusive and multidimensional conceptualization of resilience, emphasizing diverse sources of strength.

4.4. Traditions Reimagined as Spirituality and Adaptation

Religious and spiritual imagery remained a prominent feature of artistic expression, reaffirming the centrality of faith in Caribbean resilience. However, rather than serving as static artifacts of tradition, these symbols evolved to “transcend” (

Walsh, 2020) new coping mechanisms, demonstrating that faith-based resilience is dynamic rather than fixed. Families reinterpreted spiritual practices to accommodate new realities, expanding their resilience strategies beyond traditional religious frameworks. The emergence of Earthly Healing as a post-pandemic theme suggests that spirituality was not only preserved but also adapted, blending religious belief with nature-based healing practices. This fluidity in spiritual expression aligns with family resilience theory (

Walsh, 2020), which posits that shared belief systems serve as a critical mechanism for navigating adversity.

At the same time, the evolving nature of these traditions challenges the notion that resilience is solely about maintaining cultural continuity. Instead, the findings highlight the capacity of families to reinterpret traditions in ways that respond to contemporary challenges. This pattern aligns with broader post-pandemic recovery trends (

Duff et al., 2024), where natural environments are increasingly integrated into mental and emotional well-being strategies. The reliance on nature suggests an expansion of coping strategies that blend spirituality with nature-based healing, demonstrating that family resilience is not only about preserving cultural heritage but also about innovating within it. Ultimately, these findings reinforce that resilience is a dynamic process—one that involves growth, adaptation, and the continuous reimagining of traditions to sustain and strengthen the family system.

4.5. Creative Storytelling as Resilience Practice

A core contribution of this study is its demonstration that visual art is not simply a reflection of resilience but a practice through which resilience is constructed. In the Caribbean, where storytelling, ritual, and symbolism are central to family life (

Lowery, 2013), artmaking provided a culturally congruent method for processing trauma, asserting identity, and building emotional continuity.

As noted in

Gerber et al. (

2018) and

Leavy (

2020), creative expression facilitates emotional integration and offers a non-verbal space for healing. For Caribbean families, visual storytelling enabled the articulation of complex emotions and fostered intergenerational connection. These findings support the integration of arts-based methods into resilience research and practice, particularly in culturally rich yet under-resourced contexts.

4.6. Implications

The present study contributes to a growing body of family scholarship that calls for culturally grounded and context-specific approaches to understanding resilience. The use of visual art as a research and interpretive tool offers a novel pathway for identifying both resilience and distress within Caribbean families, especially during periods of acute societal disruption, such as the COVID-19 pandemic. The arts-based methodology illustrates the potential of creative expression to access emotional and relational dimensions of family life that are often obscured by more conventional, text- or speech-based methods.

By capturing how families used visual metaphors, shared symbolism, and collaborative creation, the study advances the understanding of resilience as an enacted and observable process. These visual narratives offer entry points for family scholars and practitioners to engage with the complexities of emotion, adaptation, and connection in culturally meaningful ways. In contexts where verbal expressions of distress may be limited by stigma or generational norms, artwork can offer a safe medium for surfacing internal and interpersonal experiences.

This work also has practical relevance for family life education, therapy, and resilience-building programs. Incorporating visual art into therapeutic settings can foster self-reflection, intergenerational dialogue, and collective healing. In family life education programs, art-based exercises may serve as tools to build empathy, strengthen communication, and encourage resilience practices that extend beyond crisis contexts. Community-based initiatives could similarly employ arts-based approaches to nurture cohesion, cultural pride, and coping strategies that resonate with local traditions. These applications highlight the value of treating art not only as a research tool but also as an intervention strategy adaptable to diverse family contexts.

Importantly, this study fills a critical gap in family science by centering the lived experiences of underrepresented Caribbean families. In doing so, it broadens the global scope of resilience scholarship and underscores the necessity of incorporating perspectives from low-resource regions that are often marginalized in academic discourse. The ecological, spiritual, and cultural dimensions of resilience evident in families’ artwork challenge Western-centric models that privilege verbal or individualistic accounts, pointing toward more inclusive frameworks for studying family resilience.

Finally, the findings carry implications for public health and educational policy. Arts-based resilience practices could be integrated into school curricula, community programming, or public health campaigns to promote emotional well-being and family connectedness, particularly in contexts with limited access to formal mental health services. By acknowledging and supporting the creative strategies that families already use to endure and adapt, policymakers can design interventions that are both culturally responsive and sustainable. In this way, this research on Caribbean families’ visual storytelling offers broader lessons for how art can inform resilience-oriented policies and practices in other low-resource settings worldwide.

4.7. Limitations and Future Possibilities

While this study provides important insights into the visual expressions of resilience among Caribbean families during the COVID-19 pandemic, several limitations must be considered when interpreting the findings. To begin, the study was geographically limited to families from three English-speaking Caribbean countries: Trinidad, Jamaica, and Grenada. Given the cultural, linguistic, and historical diversity of the broader Caribbean region, these findings may not fully represent the experiences of families in other nations or among diaspora communities. Broader regional sampling would allow future research to better capture the range of artistic and cultural expressions related to family resilience.

In addition, the relatively small dataset of 25 family-generated artworks may restrict the depth and variability of thematic exploration. While rich in meaning, the sample size limits the ability to generalize findings or identify statistically robust patterns. Moreover, as shown in

Table 1, the demographic composition of families differed between the pre- and post-COVID periods, which may have influenced the visual and thematic outcomes. For example, the post-COVID sample included a higher proportion of single-parent and Afro-Caribbean households, while Indo-Caribbean families were only represented in the pre-COVID group. These variations may reflect differences in socioeconomic circumstances, caregiving structures, or cultural expressions of resilience, making it difficult to attribute observed shifts in the artwork solely to the pandemic’s effects. Future studies should therefore aim to include a larger and more demographically balanced sample to enhance analytic rigor and capture subtler or less dominant resilience themes across diverse Caribbean family contexts.

Another methodological consideration is the inconsistency in accompanying descriptive narratives. Although participants were encouraged to provide contextual descriptions, not all families chose to do so. This occasionally constrained interpretive depth, particularly when visual symbolism lacked explicit explanation. Encouraging or requiring artist commentary in future studies may help mitigate this issue and support more nuanced, culturally contextual analysis.

The composition of the analysis team also introduced potential interpretive variation. Researchers brought diverse academic and experiential backgrounds to the project, which is an asset for reflexivity, but one that also carried a risk of inconsistent analysis. While collaborative coding and regular debriefing were employed to ensure rigor, future research would benefit from enhanced strategies, such as structured coding protocols or training modules, to support consistency across team members.

These limitations open several avenues for future inquiry. As Caribbean societies continue to recover and adapt post-pandemic, it would be valuable to explore how families’ creative expressions have evolved in the absence of severe stress. Longitudinal research, particularly involving the same families over time, could offer insight into how visual expressions of resilience shift alongside changing emotional and relational dynamics.

Further, comparative studies involving additional Caribbean nations and diaspora populations could illuminate how migration, displacement, and transnational ties shape artistic coping strategies. Exploring a wider variety of artistic media, including digital art, sculpture, or performance, could also expand the methodological range of future research and offer a fuller picture of creative adaptation.

Incorporating qualitative methods, such as interviews, narrative elicitation, or arts-based participatory workshops, would deepen the interpretive process and offer insight into the personal and collective meanings behind the artworks. These approaches could enrich understandings of how families use art not only to document experiences but to actively process, resist, and transform hardship.

Finally, exploring the role of institutional, governmental, and community-based support for the arts could reveal how broader systems contribute to or hinder creative family coping. Assessing the reach and impact of public health campaigns, cultural initiatives, or school-based art programs may generate useful policy recommendations for supporting resilience through creative expression in future crises. Importantly, this line of research can also guide comparative family science across cultures, helping to identify both culturally specific and cross-cultural dimensions of how art mediates family resilience. By situating Caribbean experiences alongside those of families in other global contexts, scholars can advance a more inclusive and culturally attuned understanding of resilience in family science.

5. Conclusions

This study contributes to the growing body of literature on culturally relevant understandings of family resilience by examining visual creative expressions of Caribbean families before and after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. In a period marked by widespread disruption, uncertainty, and emotional strain, families turned to creative methods as a means of coping, connection, and communication. The findings illustrate that resilience is not a static trait but a dynamic process of creative adaptation, rooted in cultural values, collective rituals, and emotionally expressive artmaking.

Amid the COVID-19 crisis, visual art served as more than a coping strategy; it became a vehicle for emotional integration, family bonding, and intergenerational dialogue. Through shared artistic practices, families transformed distress into symbols of hope, spiritual continuity, and ecological connection. These creative behaviors reflect a multisystemic process of resilience, in which individuals, relationships, and cultural systems interact to support recovery and meaning-making.

Key themes such as spiritual grounding, familial cohesion, and communal care persisted throughout the pandemic, while emergent motifs, such as nature-based healing and the open expression of negative emotion, signaled innovative responses to novel challenges. These shifts demonstrate how families used creative adaptation to respond flexibly to the psychological and relational demands of the pandemic. Artmaking, in this context, was not merely reflective but generative. It enabled families to imagine new ways of being together in the face of hardship.

Importantly, the study reinforces the need for a broader conceptualization of resilience, particularly in underrepresented and resource-limited communities. Rather than emphasizing individual psychological traits, the findings highlight the power of culturally embedded, symbolic, and non-verbal expressions of strength. Creative behavior, whether through visual metaphor, collaborative creation, or spiritual symbolism, emerged as a vital resilience practice during COVID-19, revealing new dimensions of healing that are often overlooked in conventional models.

For scholars and practitioners in family studies, psychology, and the creative arts, these insights underscore the value of integrating arts-based methodologies into research and intervention design. As families continue to navigate the long-term social and emotional impacts of COVID-19, future inquiry should deepen this work by examining how creative behavior evolves over time, across regions, and within diverse media. Doing so will expand our understanding of how art functions not just as expression but as action that transforms crisis into connection and loss into meaning.