Protein Adsorption and Cell Adhesion on Metallic Biomaterial Surfaces

Abstract

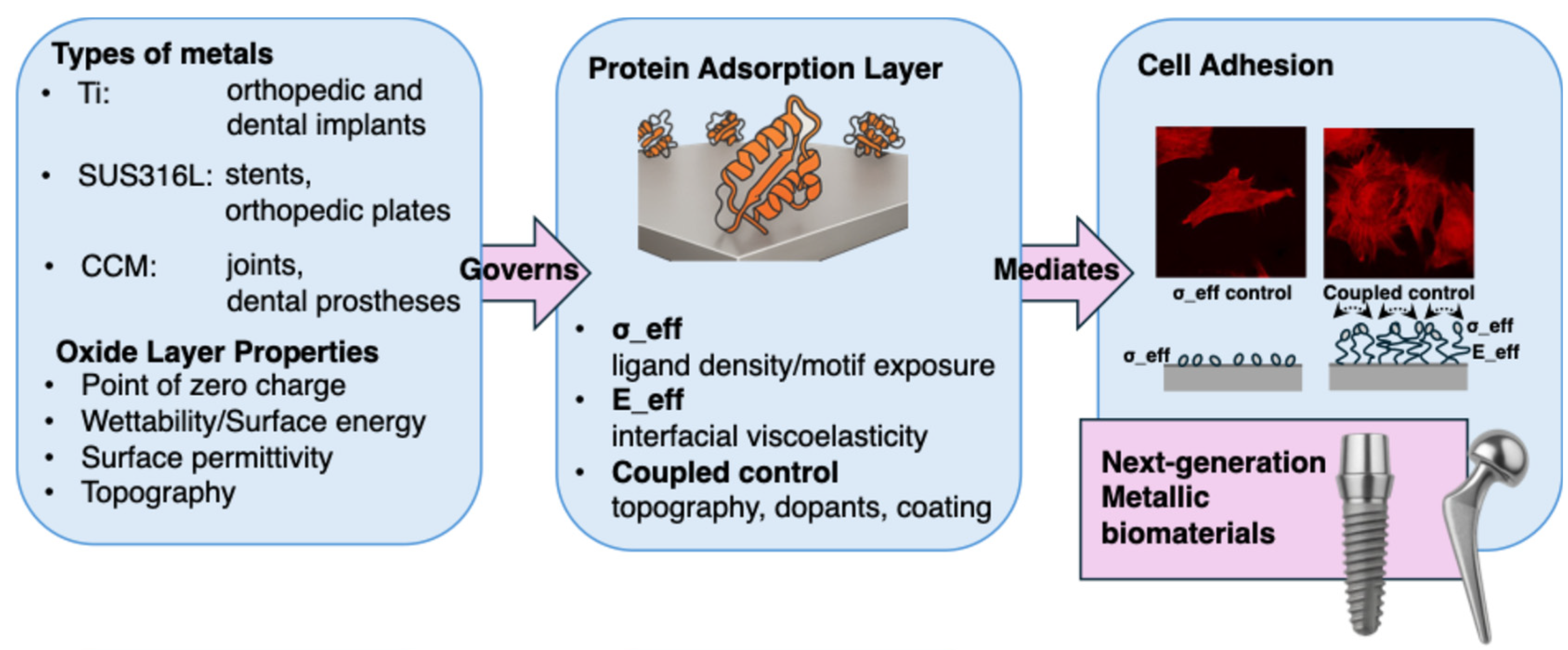

1. Introduction

2. Physicochemical Properties of Surface Affecting Protein Adsorption

3. Protein Adsorption on to Metallic Biomaterials

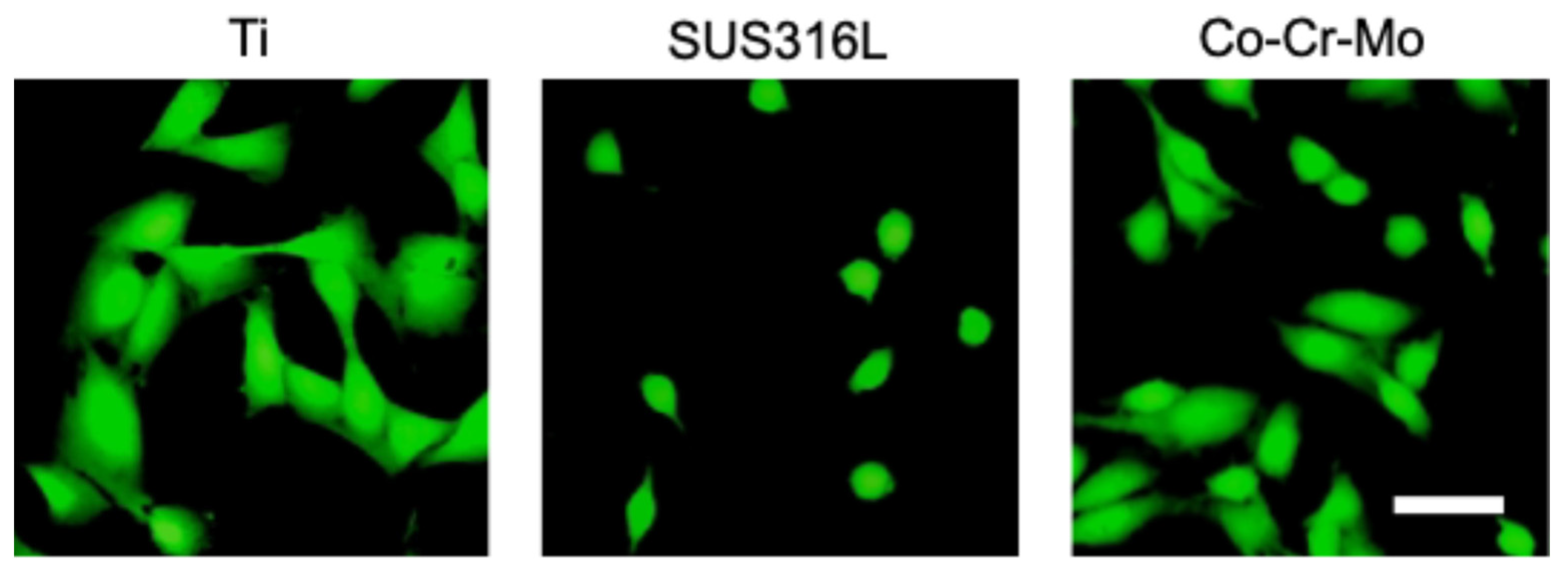

3.1. Titanium

3.2. Stainless Steel

3.3. Co-Cr Alloy

4. Surface Modification Strategies for Controlling Protein Adsorption and Cellular Responses

4.1. Design Principles for σ_eff and E_eff

4.1.1. Geometirical Design of σ_eff

4.1.2. Physicochemical Design of E_eff

4.2. Implementation Strategies to Raise σ_eff

| Strategy | Material | Anchor | Presented Motif | Within-Study Outcomes | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solid binding peptide | Ti | minTBP-1 (RKLPDA) | minTBP-1-RGD | MC3T3-E1: adhesion ↑, spreading ↑; some studies report osteogenic markers ↑ | [89,90] |

| SUS316L | SUS-binding peptide (SBP) | SBP-RGD | HUVEC: adhesion/retention ↑ | [91] | |

| Co-Cr-Mo | CCM-binding peptide (CBP) | CBP-RGD | HUVEC: adhesion ↑; MC3T3-E1: proliferation ↑, osteogenesis markers ↑ | [92,93] | |

| Self-assembled monolayer (SAM) | Au | Alkanetiol SAM | RGD GRGDS GRGDS + PHSRN | Baby hamster kidney: adhesion ↑ 3T3 Swiss fibroblasts: cytoskeleton, focal adhesion ↑ NIH3T3: spreading, focal adhesion ↑ | [96,97] |

| Au Fe-MPN | Click-SAM | RGDSP cRGD | hMSC: adhesion, spreading, focal adhesion ↑ NIH3T3: adhesion, proliferation, migration ↑ | [98,99] | |

| Ionic modification | TiO2 | O ion beam | [100] | ||

| bioactive glass | Ag ion exchange | Albumin Fibronectin | Human gingval fibroblasts: adhesion, differentiation ↑ | [101] | |

| Ti | Ca ion coating | Serum protein | Primary human alveolar osteoblasts: adhesion (ND), osteocalcin, procollagen type I ↑ | [102] |

4.3. Implementation Strategies to Tune E_eff

| Strategy | Material | Coating | Adlayer Metric | Value (vs. Bare) | Within-Study Outcomes | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polyphenol film | Ti | Tannic acid | ΔD/thickness of FBS | ~2×/1.3–1.7× | Fibroblasts: adhesion ↑ | [83] |

| Inorganic layer | Au | Hydroxy apatite | ΔD/thickness of FBS | ~2×/2–4× | Viscoelasticity of FBS ↑ Hepatocyte: morphological change | [104,112] |

| Tether rigidity | Au | cRGD + spacer | Spacer type | Polyproline vs. aminohexanoic acid | Polyproline spacer: adhesion, focal adhesion ↑ | [113] |

| Hydrated brush | Ti | PEG | thickness of PEG-RGD | 1.5–2× in air | MC3T3-E1: differentiation↑ Osteoblast: osteogenesis in vivo ↑ | [107,108] |

| Glass | PEG | PEG length | Long/short = 318 nm/9.5 nm | Longer PEG: focal adhesion, spreading ↓ | [114] | |

| Ti | Zwitter ionic polymer | protein adsorption | 0.1–0.3× | MC3T3-E1: differentiation ↑ | [109] |

4.4. Coupled Control of σ_eff and E_eff

5. Perspective

5.1. Three-Dimensional Modification of Porous Metal Internal Walls: Development of Material-Inspired Biomaterials

5.2. Bridging Hierarchical Understanding Gaps: From Molecular to Tissue Level

5.3. Sustainability-Oriented Design of Metallic Biomaterials

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Marin, E.; Lanzutti, A. Biomedical Applications of Titanium Alloys: A Comprehensive Review. Materials 2024, 17, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, E. History of dental biomaterials: Biocompatibility, durability and still open challenges. Herit. Sci. 2023, 11, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Damaty, S.; Hazubski, S.; Otte, A. ArtiFacts: Creating a 3-D CAD Reconstruction of the Historical Roman Capua Leg. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2021, 479, 1911–1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczęsny, G.; Kaczmarek, M.; Politis, D.J.; Kowalewski, Z.L.; Łazarski, A.; Szolc, T. A review on biomaterials for orthopedic surgery and traumatology: From past to present. Materials 2022, 15, 3622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Thouas, G.A. Metallic implant biomaterials. Mater. Sci. Eng. R 2015, 87, 1–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoellwarth, J.S.; Tetsworth, K.; Akhtar, M.A.; Muderis, M.A. The Clinical History and Basic Science Origins of Osseointegration. Adv. Orthop. 2022, 2022, 7960559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marin, E.; Boschetto, F.; Pezzotti, G. Biomaterials and biocompatibility: An historical overview. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2020, 108, 1617–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarraf, M.; Ghomi, E.R.; Alpour, S.; Ramakrishna, S.; Sukiman, N.L. A state-of-the-art review of the fabrication and characteristics of titanium and its alloys for biomedical applications. Biodes. Manuf. 2021, 5, 371–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GBD 2021 Osteoarthritis Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of osteoarthritis, 1990–2020 and projections to 2050: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Rheumatol. 2023, 5, e508–e522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Xie, S.; Xu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Sun, Q.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, T. From Pain to Progress: Comprehensive Analysis of Musculoskeletal Disorders Worldwide. J. Pain Res. 2024, 17, 3455–3472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chowdhury, A.R.; Graham, P.; Schofield, D.; Costa, D.S.J.; Nicholas, M. Productivity outcomes from chronic pain management interventions in the working-age population: A systematic review. Pain 2024, 165, 1233–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dykhouse, G.L.; Bratescu, R.A.; Kashlan, O.N.; McGrath, L.; Härtl, R.; Elsayed, G.A. Trends in spinal implant utilization and pricing. J. Craniovertebr. Junctio. Spine 2024, 15, 404–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, F.; Romanos, G.E. The role of primary stability for successful immediate loading of dental implants. A literature review. J. Dent. 2010, 38, 612–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tande, A.J.; Patel, R. Prosthetic Joint Infection. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2014, 27, 302–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Chiang, S.Y.V.; Gawkrodger, D.J. The contribution of metal allergy to the failure of metal alloy implants, with special reference to titanium: Current knowledge and controversies. Contact Dermat. 2024, 90, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Zhou, J.; Qian, Y.; Zhao, L. Antibacterial coatings on orthopedic implants. Mater. Today Bio. 2023, 19, 100586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanawa, T. Biocompatibility of titanium from the viewpoint of its surface. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 2022, 23, 457–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsh, S.L.; McKenzie, D.R.; Nosworthy, N.J.; Denman, J.A.; Sezerman, O.U.; Bilek, M.M.M. The Vroman effect: Competitive protein exchange with dynamic multilayer protein aggregates. Colloids Surf. B 2013, 103, 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter-Bisson, Z.W.; Hedberg, Y.S. Revisiting the Vroman effect: Mechanisms of competitive protein exchange on surfaces. Colloids Surf. B 2025, 255, 114927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barberi, J.; Spriano, S. Titanium and protein adsorption: An overview of mechanisms and effects of surface features. Materials 2021, 14, 1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brash, J.L.; Horbett, T.A.; Latour, R.A.; Tengvall, P. The blood compatibility challenge. Part 2: Protein adsorption phenomena governing blood reactivity. Acta Biomater. 2019, 94, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bañuelos, J.L.; Borguet, E.; Brown, G.E., Jr.; Cygan, R.T.; DeYoreo, J.J.; Dove, P.M.; Gaigeot, M.; Geiger, F.M.; Gibbs, J.M.; Grassian, V.H.; et al. Oxide- and silicate-water interfaces and their roles in technology and the environment. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 6413–6544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maleki, F.; Pacchioni, G. Probing the nature of Lewis acid sites on oxide surfaces with 31P(CH3)3 NMR: A theoretical analysis. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2022, 24, 19773–19782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonsson, C.M.; Jonsson, C.L.; Sverjensky, D.A.; Cleaves, H.J.; Hazen, R.M. Attachment of L-glutamate to rutile (alpha-TiO(2)): A potentiometric, adsorption, and surface complexation study. Langmuir 2009, 25, 12127–12135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agosta, L.; Fiore, L.; Colozza, N.; Pérez-Ropero, G.; Lyubartsev, A.; Arduini, F.; Hermansson, K. Adsorption of Glycine on TiO2 in Water from on-the-fly Free-Energy Calculations and In Situ Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy. Langmuir 2024, 40, 12009–12016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barreto, M.S.C.; Elzinga, E.J.; Alleoni, L.R.F. The molecular insights into protein adsorption on hematite surface disclosed by in-situ ATR-FTIR/2D-COS study. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 13441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Laaksonen, A.; Gao, Q.; Ji, X. Molecular mechanistic insights into the ionic-strength-controlled interfacial behavior of proteins on a TiO2 surface. Langmuir 2021, 37, 11499–11507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, G.; Liang, Z.; Yu, Z.; Li, M.; Yang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, C.; Xue, C.; Shi, L.; et al. Engineering the hydroxyl content on aluminum oxyhydroxide nanorod for elucidating the antigen adsorption behavior. npj Vaccines 2022, 7, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosmulski, M. The pH dependent surface charging and points of zero charge. X. Update. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2023, 319, 102973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crago, M.; Lee, A.; Hoang, T.P.; Talebian, S.; Naficy, S. Protein adsorption on blood-contacting surfaces: A thermodynamic perspective to guide the design of antithrombogenic polymer coatings. Acta Biomater. 2024, 180, 46–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Ghannam, A.; Hamazawy, E.; Yehia, A. Effect of thermal treatment on bioactive glass microstructure, corrosion behavior, ζ potential, and protein adsorption. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2001, 55, 387–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabe, M.; Verdes, D.; Seeger, S. Understanding protein adsorption phenomena at solid surfaces. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2011, 162, 87–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komorek, P.; Martin, E.; Jachimska, B. Adsorption and Conformation Behavior of Lysozyme on a Gold Surface Determined by QCM-D, MP-SPR, and FTIR. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva-Bermudez, P.; Rodil, S.E. An overview of protein adsorption on metal oxide coatings for biomedical implants. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2013, 233, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piontek, S.M.; Borguet, E. Vibrational spectroscopy of geochemical interfaces. Surf. Sci. Rep. 2023, 78, 100606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oosterlaken, B.M.; van den Bruinhorst, A.; de With, G. On the use of probe liquids for surface energy measurements. Langmuire 2023, 39, 16701–16711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lößlein, S.M.; Merz, R.; Müller, D.W.; Kopnarske, M.; Mücklich, F. An in-depth evaluation of sample and measurement induced influences on static contact angle measurements. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 19389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Dong, H.; Wen, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, S. Surface Free Energy of Titanium Disks Enhances Osteoblast Activity by Affecting the Conformation of Adsorbed Fibronectin. Front. Mater. 2022, 9, 840813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, Y.; Meng, H.; Du, Z.; Zhang, W.; Ma, Q.; Huang, Y.; Cui, L.; Lei, Y.; Yang, Z. Bioinspired super-hydrophilic zwitterionic polymer armor combats thrombosis and infection of vascular catheters. Bioact. Mater. 2024, 37, 493–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Dodiuk, H. Effect of protein adsorption on air plastron behavior of a superhydrophobic surface. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 12, 58096–58103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuyama, H.; Sugawara, Y.; Yamaguchi, T. Machine-learning-aided understanding of protein adsorption on zwitterionic polymer brushes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 25236–25245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolivet, A.; Labbé, C.; Frilay, C.; Debieu, O.; Marie, P.; Horcholle, B.; Lemarié, F.; Portier, X.; Grygiel, C.; Duprey, S.; et al. Structural, optical, and electrical properties of TiO2 thin films deposited by ALD: Impact of the substrate, the deposited thickness and the deposition temperature. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2023, 608, 155214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.H.; Chen, Z.H.; Nguyen, D.T.; Tseng, C.M.; Chen, C.S.; Chang, J.H. Blood coagulation on titanium dioxide films with various crystal structures on titanium implant surfaces. Cells 2022, 11, 2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, J. High dielectric constant oxides. Eur. Phys. J. Appl. Phys. 2004, 28, 265–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, K.F.; Frederikse, H.P.R. Compilation of the Static Dielectric Constant of Inorganic Solids. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 1973, 2, 313–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lide, D.R. (Ed.) CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, 85th ed.; Section 12: Properties of solids; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2004; pp. 12-48–12-56. [Google Scholar]

- Nigro, R.L.; Fiorenza, P.; Greco, G.; Schilliro, E.; Roccaforte, F. Structural and insulating behaviour of high-permittivity binary oxide thin films for silicon carbide and gallium nitride electronic devices. Materials 2022, 15, 830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G.E.; Henrich, V.E.; Casey, W.H.; Clark, D.L.; Eggleston, C.; Felmy, A.; Goodman, D.W.; Grätzel, M.; Maciel, G.; McCarthy, M.I.; et al. Metal oxide surfaces and their interactions with aqueous solutions and microbial organisms. Chem. Rev. 1999, 99, 77–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarti, P. Geometry of interaction of metal ions with histidine residues in proteins. Proteins 1990, 8, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, J.C.; Estroff, L.A.; Kriebel, J.K.; Nuzzo, R.G.; Whitesides, G.M. Self-assembled monolayers of thiolates on metals as a form of nanotechnology. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 1103–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muir, J.M.R.; Costa, D.; Idriss, H. DFT Computational Study of the RGD Peptide Interaction with the Rutile TiO2 (110) Surface. Surf. Sci. 2014, 624, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, R.G. Hard and soft acids and bases. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1963, 85, 3533–3539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarano, A.; Postiglione, F.; Khater, A.G.A.; Al-Hamed, F.S.; Lorusso, F. A Novel Technique to Increase the Thickness of TiO2 of Dental Implants by Nd: DPSS Q-sw Laser Treatment. Materials 2020, 13, 4178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinpour, S.; Tang, F.; Wang, F.; Livingstone, R.A.; Schlegel, S.; Ohto, T.; Bonn, M.; Nagata, Y.; Backus, E.H.G. Chemisorbed and physisorbed water at the TiO2/water interface. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2017, 8, 2195–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiji, A.; Hanawa, T.; Yokoi, T.; Chen, P.; Ashida, M.; Kawashita, M. Time transient of calcium and phosphate ion adsorption by rutile crystal facets in Hanks’ solution characterized by XPS. Langmuir 2021, 37, 3597–3604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiji, A.; Hanawa, T.; Shimabukuro, M.; Chen, P.; Ashida, M.; Ishikawa, K. Initial formation kinetics of calcium phosphate on titanium in Hanks’ solution characterized using XPS. Surf. Interface Anal. 2020, 53, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellingsen, J.E. A study on the mechanism of protein adsorption to TiO2. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1991, 142, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barberi, J.; Barberi, J.; Mandrile, L.; Napione, L.; Giovannozzi, A.M.; Rossi, A.M.; Vitale, A.; Yamaguchi, S.; Spriano, S. Albumin and fibronectin adsorption on treated titanium surfaces for osseointegration: An advanced investigation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2022, 599, 154023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki, F.; Liberto, G.D.; Pacchioni, G. pH- and Facet-Dependent Surface Chemistry of TiO2 in aqueous environment from first principles. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 11216–11224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Givens, B.E.; Xu, Z.; Fiegel, J.; Grassian, V.H. Bovine serum albumin adsorption on SiO2 and TiO2 nanoparticle surfaces at circumneutral and acidic pH: A tale of two nano-bio surface. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2017, 493, 334–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Långberg, M.; Örnek, C.; Evertsson, J.; Harlow, G.S.; Linpé, W.; Rullik, L.; Carlà, F.; Felici, R.; Bettini, E.; Kivisäkk, U.; et al. Redefining passivity breakdown of super duplex stainless steel by electrochemical operando synchrotron near surface X-ray analyses. npj Mater. Degrad. 2019, 3, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brüesch, P.; Müller, K.; Atrens, A.; Neff, H. Corrosion of Stainless Steels in Chloride Solution an XPS Investigation of Passive Films. Appl. Phys. A 1985, 38, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanawa, T.; Hiromoto, S.; Asami, K. Characterization of the surface oxide film of a Co–Cr–Mo alloy after being located in quasi-biological environments using XPS. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2001, 183, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgson, A.W.E.; Kurz, S.; Virtanen, S.; Fervel, V.; Olsson, C.-O.A.; Mischler, S. Passive and transpassive behaviour of CoCrMo in simulated biological solutions. Electrochim. Acta 2004, 49, 2167–2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duderija, B.; González-Orive, A.; Ebbert, C.; Neßlinger, V.; Keller, A.; Grundmeier, G. Electrode Potential-Dependent Studies of Protein Adsorption on Ti-6Al-4V Alloy. Molecules 2023, 29, 5109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, Y.; Saito, H.; Tsutsumi, Y.; Doi, H.; Imai, H.; Hanawa, T. Active Hydroxyl Groups on Surface Oxide Film of Titanium, 316L Stainless Steel, and Cobalt-Chromium-Molybdenum Alloy and Its Effect on the Immobilization of Poly(Ethylene Glycol). Mater. Trans. 2008, 49, 805–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundin, M.; Hedberg, Y.; Jiang, T.; Johnson, C.M.; Blomberg, E.; Wallinder, I.O. Adsorption and protein-induced metal release from chromium metal and stainless steel. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2012, 366, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merritt, K.; Brown, S.A. Effect of proteins and pH on fretting corrosion and metal ion release. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1988, 22, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atapour, M.; Wallinder, I.O.; Hedberg, Y. Stainless steel in simulated milk and whey protein solutions—Influence of grade on corrosion and metal release. Electrochim. Acta 2020, 331, 135428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varmaziar, S.; Atapour, M.; Hedberg, Y.S. Corrosion and metal release characterization of stainless steel 316L weld zones in whey protein solution. npj Mater. Degrad. 2022, 6, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Yan, H.; Zhang, B.; Tang, A.; Li, Y. Unveiling the effect of bovine serum albumin on the corrosion resistance of high nitrogen stainless steel for cardiac stents. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 33, 7113–7122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Yang, H.; Su, Y.; Qiao, L. Albumin adsorption on CoCrMo alloy surfaces. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 18403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, K.; Chen, J.; Wang, T.; Su, Y.; Qiao, L.; Yan, Y. Effect of surface energy on protein adsorption behaviours of treated CoCrMo alloy surfaces. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 520, 146354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engler, A.; Bacakova, L.; Newman, C.; Hategan, A.; Griffin, M.; Discher, D. Substrate compliance versus ligand density in cell on gel responses. Biophys. J. 2004, 86, 617–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagöz, Z.; Rijns, L.; Dankers, P.Y.W.; van Griensven, M.; Carlier, A. Towards understanding the messengers of extracellular space: Computational models of outside-in integrin reaction networks. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2020, 19, 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, K.; Pandey, A.; Wang, H.; Chung, T.; Nemati, A.; Kanchanawong, P.; Sheetz, M.P.; Cai, H.; Changede, R. TiO2 nano-biopatterning reveals optimal ligand presentation for cell–matrix adhesion formation. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, e2309284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, O.; Cooper-White, J.; Janmey, P.A.; Mooney, D.J.; Shenoy, V.B. Effect of extracellular matrix viscoelasticity on cellular behaviour. Nature 2020, 584, 535–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blache, U.; Ford, E.M.; Ha, B.; Rijns, L.; Chaudhuri, O.; Dankers, P.Y.W.; Kloxin, A.M.; Snedeker, J.G.; Gentleman, E. Engineered hydrogels for mechanobiology. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers 2022, 2, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Ling, S.D.; Liang, K.; Chen, Y.; Niu, Y.; Sun, L.; Li, J.; Du, Y. Viscoelasticity of ECM and cells—Origin, measurement and correlation. Mechanobiol. Med. 2024, 2, 100082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nour, S.; Shabani, S.; Swiderski, K.; Lynch, G.S.; O’Connor, A.J.; Qiao, G.; Heath, D.E. Engineering nanoclusters of cell adhesive ligands on biomaterial surfaces: Superior cell proliferation and myotube formation for skeletal muscle tissue regeneration. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2025, 14, 2402991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, P.; Zhang, L.; Xu, T.; Ahn, S.; Sharma, U.; Yu, H.; Strohmeyer, N.; Müller, D.J. Mammalian cells measure the extracellular matrix area and respond through switching the adhesion state. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 6870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oria, R.; Wiegand, T.; Escribano, J.; Elosegui-Artola, A.; Uriarte, J.J.; Moreno-Pulido, C.; Platzman, I.; Delcanale, P.; Albertazzi, L.; Navajas, D. Force loading explains spatial sensing of ligands by cells. Nature 2017, 552, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogala, A.; Zaytseva-Zotova, D.; Oreja, E.; Barrantes, A.; Tiainen, H. Combining QCM-D with live-cell imaging reveals the impact of serum proteins on the dynamics of fibroblast adhesion on tannic acid-functionalised surfaces. Biomater. Sci. 2024, 12, 3345–3359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreeva, T.; Akbas, O.; Jahm, A.; Greuling, A.; Winkel, A.; Stiesch, M.; Krastev, R. Controlling cellular behavior by surface design of titanium-based biomaterials. In Vivo 2025, 39, 1786–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.S.; Pham, D.A.; Zhang, H.; Rabanel, J.M.; Hassanpour, N.; Banquy, X. Layer-by-Layer deposition of a polycationic bottlebrush polymer with hyaluronic acid reveals unusual assembly mechanism and selective effect on cell adhesion and fate. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2402960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilanova, O.; Martinez-Serra, A.; Monopoli, M.P.; Franzese, G. Characterizing the hard and soft nanoparticle-protein corona with multilayer adsorption. Front. Nanotechnol. 2025, 6, 1531039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, L.; Li, T.; Wang, L.; Shi, X.; Fan, Y.; Du, C.; Wang, Y. Mechanistic insights into the adsorption and bioactivity of fibronectin on surfaces with varying chemistries by a combination of experimental strategies and molecular simulations. Bioact. Mater. 2021, 6, 3125–3135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migita, S. Solid-binding peptide for enhancing biocompatibility of metallic biomaterials. SynBio 2024, 2, 329–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sano, K.; Shiba, K. A hexapeptide motif that electrostatically binds to the surface of titanium. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 14234–14235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal, G.; Blanchi, T.; Mieszawska, A.J.; Calabrese, R.; Rossi, C.; Vigneron, P.; Duval, J.-L.; Kaplan, D.L.; Egles, C. Enhanced cellular adhesion on titanium by silk functionalized with titanium binding peptides. Acta Biomater. 2013, 9, 4935–4943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakaguchi-Mikami, A.; Fujimoto, K.; Taguchi, T.; Karube, I.; Yamazaki, T. A novel biofunctionalizing peptide for metallic alloy. Biotechnol. Lett. 2020, 42, 747–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migita, S.; Sakashita, K.; Saito, Y.; Suyalatu; Yamazaki, T. Co–Cr–Mo alloy binding peptide as molecular glue for constructing biomedical surfaces. J. Appl. Biomater. Funct. Mater. 2020, 18, 2280800020924739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migita, S.; Wakabayashi, K.; Yamazaki, T. Binding stability of peptides to Co–Cr–Mo alloy affects proliferation and differentiation of osteoblast. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2022, 119, 1157–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redondo-Gómez, C.; Parreira, P.; Martins, M.C.L.; Azevedo, H.S. Peptide-based self-assembled monolayers (SAMs): What peptides can do for SAMs and vice versa. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2024, 53, 3714–3773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Mrksich, M. The synergy peptide PHSRN and the adhesion peptide RGD mediate cell adhesion through a common mechanism. Biochemistry 2004, 43, 15811–15821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.H.; Mofrad, M.R.K. Cell adhesion and detachment on gold surfaces modified with a thiol-functionalized RGD peptide. Biomaterials 2011, 32, 7286–7296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nöth, M.; Zou, Z.; El-Awaad, I.; de Lencastre Novaes, L.C.; Dilarri, G.; Davari, M.D.; Ferreira, H.; Jakob, F.; Schwaneberg, U. A peptide-based coating toolbox to enable click chemistry on polymers, metals, and silicon through sortagging. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2021, 118, 1520–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shou, Z.; Bai, Z.; Huo, K.; Zheng, S.; Shen, Y.; Zhou, H.; Huang, X.; Meng, H.; Xu, C.; Wu, S.; et al. Immobilizing c(RGDfc) on the surface of metal-phenolic networks by thiol-click reaction for accelerating osteointegration of implant. Mater. Today Bio. 2024, 25, 101017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hudalla, G.A.; Murphy, W.L. Using “click” chemistry to prepare SAM substrates to study stem cell adhesion. Langmuir 2009, 25, 5737–5746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, M.; Mo, W.; Qi, H.; Ni, Y.; Wang, R.; Shen, K.; Zhang, F.; Jiang, S.; Zhang, X.; Chen, L.; et al. Oxygen ion implantation improving cell adhesion on titanium surfaces through increased attraction of fibronectin PHSRN domain. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2022, 11, 2101983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacopo Barberi, J.; Mandrile, L.; Giovannozzi, A.M.; Miola, M.; Napione, L.; Rossi, A.M.; Vitale, A.; Yamaguchi, S.; Spriano, S. Effect on albumin and fibronectin adsorption of silver doping via ionic exchange of a silica-based bioactive glass. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 13728–13741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Gavilán, F.; Cerqueira, A.; Anitua, E.; Tejero, R.; García-Arnáez, I.; Martinez-Ramos, C.; Ozturan, S.; Izquierdo, R.; Azkargorta, M.; Elortza, F.; et al. Protein adsorption/desorption dynamics on Ca-enriched titanium surfaces: Biological implications. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2021, 26, 715–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anitua, E.; Tejero, R. Provisional matrix formation at implant surfaces-the bridging role of calcium ions. Cells 2022, 29, 3048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tagaya, M.; Ikoma, T.; Migita, S.; Okuda, M.; Takemura, T.; Hanagata, N.; Yoshioka, T.; Tanaka, J. Fetal bovine serum adsorption onto hydroxyapatite sensor monitoring by quartz crystal microbalance with dissipation technique. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2010, 173, 176–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; van Rijt, S. DNA modified MSN-films as versatile biointerfaces to study stem cell adhesion processes. Colloids Surf. B 2022, 215, 112495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosatti, S.; Schwartz, Z.; Campbell, C.; Cochran, D.L.; VandeVondele, S.; Hubbell, J.A.; Denzer, A.; Simpson, J.; Wieland, M.; Lohmann, C.H.; et al. RGD-containing peptide GCRGYGRGDSPG reduces enhancement of osteoblast differentiation by poly(L-lysine)-graft-poly(ethylene glycol)-coated titanium surfaces. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2004, 68, 458–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.W.; Kurashima, K.; Tsutsumi, Y.; An, C.H.; Suh, J.Y.; Doi, H.; Nomura, N.; Noda, K.; Hanawa, T. Bone healing of commercial oral implants with RGD immobilization through electrodeposited poly(ethylene glycol) in rabbit cancellous bone. Acta Biomater. 2011, 7, 3222–3229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oya, K.; Tanaka, Y.; Saito, H.; Kurashima, K.; Nogi, K.; Tsutsumi, H.; Tsutsumi, Y.; Doi, H.; Nomura, N.; Hanawa, T. Calcification by MC3T3-E1 cells on RGD peptide immobilized on titanium through electrodeposited PEG. Biomaterials 2009, 30, 1281–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Jia, E.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, H.; Tan, Y.; Deng, Z. Titanium surface-grafted zwitterionic polymers with an anti-polyelectrolyte effect enhances osteogenesis. Colloids Surf. B 2023, 226, 113293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Shi, J.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, W.; Liao, H.; Liu, G. Rapid fabrication of zwitterionic coating on 316 L stainless steel surface for marine biofouling resistance. Prog. Org. Coat. 2021, 161, 106552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Es-Souni, M.; Es-Souni, M.; Bakhti, H.; Gülses, A.; Fischer-Brandies, H.; Açil, Y.; Wiltfang, J.; Flörke, C. A bacteria and cell repellent zwitterionic polymer coating on titanium base substrates towards smart implant devices. Polymers 2021, 13, 2472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagaya, M.; Yamazaki, T.; Migita, S.; Hanagata, N.; Ikoma, T. Hepatocyte adhesion behavior on modified hydroxyapatite nanocrystals with quartz crystal microbalance. Bioceram. Dev. Appl. 2011, 1, 110157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallarola, D.; Bochen, A.; Boehm, H.; Rechenmacher, F.; Sobahi, T.R.; Spatz, J.P.; Kessler, H. Interface immobilization chemistry of cRGD-based peptides regulates integrin mediated cell adhesion. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2014, 24, 943–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attwood, S.J.; Cortes, E.; Haining, A.W.M.; Robinson, B.; Li, D.; Gautrot, J.; del Río Hernández, A. Adhesive ligand tether length affects the size and length of focal adhesions and influences cell spreading and attachment. Sci. Res. 2016, 6, 34334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegelmeyer, T.; de Sousa, K.M.; Liao, T.Y.; Lartizien, R.; Delay, A.; Vollaire, J.; Josserand, V.; Linklater, D.; Le, P.H.; Coll, J.L.; et al. Multifunctional micro/nano-textured titanium with bactericidal, osteogenic, angiogenic and anti-inflammatory properties: Insights from in vitro and in vivo studies. Mater. Today Bio. 2025, 32, 101710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janco, E.W.; Hulander, M.; Andersson, M. Curvature-dependent effects of nanotopography on classical immune complement activation. Acta Biomater. 2018, 74, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehm, R.D.; Skoog, S.A.; Diaz-Diestra, D.M.; Goering, P.L.; Dair, B.J. Influence of titanium nanoscale surface roughness on fibrinogen and albumin protein adsorption kinetics and platelet responses. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2024, 112, 373–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukaszewska-Kuska, M.; Wirstlein, P.; Majchrowski, R.; Dorocka-Bobkowska, B. The effects of titanium topography and chemical composition on human osteoblast cell. Physiol. Res. 2021, 70, 413–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osman, M.A.; Alamoush, R.A.; Kushnerv, E.; Seymour, K.G.; Shawcross, S.; Yates, J.M. In-vitro phenotypic response of human osteoblasts to different degrees of titanium surface roughness. Dent. J. 2022, 10, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matos, G.R.M. Surface roughness of dental implant and osseointegration. J. Maxillofac. Oral Surg. 2021, 20, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migita, S.; Wakabayashi, K. Analysis of disordered abrasive scratches on titanium surfaces and their impact on nuclear translocation of yes-associated protein. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 21705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migita, S.; Yamaguchi, T. Initial adhesion behavior of osteoblast on titanium with sub-micron scale roughness. Recent Prog. Mater. 2020, 2, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migita, S.; Araki, K. Effect of nanometer scale surface roughness of titanium for osteoblast function. AIMS Bioeng. 2017, 4, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migita, S.; Okuyama, S.; Araki, K. Sub-micrometer scale surface roughness of titanium reduces fibroblasts function. J. Appl. Biomater. Funct. Mater. 2016, 14, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komatsu, K.; Matsuura, T.; Cheng, J.; Kido, D.; Park, W.; Ogawa, T. Nanofeatured surfaces in dental implants: Contemporary insights and impending challenges. Int. J. Implant Dent. 2024, 10, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shu, T.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, G.; Pan, Y.; He, G.; Cheng, Y.; Li, A.; Pei, D. Enhanced osseointegration by the hierarchical micro-nano topography on selective laser melting Ti-6Al-4V dental implants. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 8, 621601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Wu, J.; Lv, S.; Xu, D.; Li, S.; Hou, W.; Wang, C.; Yu, D. Synergistic effect of hierarchical topographic structure on 3D-printed Titanium scaffold for enhanced coupling of osteogenesis and angiogenesis. Mater. Today Bio. 2023, 23, 100866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Tang, Y.; Wang, K.; Zhou, X.; Xiang, L. Nanostructured titanium implant surface facilitating osseointegration from protein adsorption to osteogenesis: The example of TiO2 NTAs. Int. J. Nanomed. 2022, 17, 1865–1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Bauer, S.; von der Mark, K.; Schmuki, P. Nanosize and vitality: TiO2 nanotube diameter directs cell fate. Nano Lett. 2007, 7, 1686–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.; Brammer, K.S.; Li, Y.S.J.; Teng, D.; Engler, A.J.; Chien, S.; Jin, S. Stem cell fate dictated solely by altered nanotube dimension. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 2130–2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Kong, K.; Tong, Z.; Qiao, H.; Jin, M.; Wu, X.; Ouyang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zhai, Z.; Li, H. TiO2 nanotube topography enhances osteogenesis through filamentous actin and XB130-protein-mediated mechanotransduction. Acta Biomater. 2024, 177, 525–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negrescu, A.M.; Ionascu, I.; Necula, M.G.; Tudor, N.; Kamaleev, M.; Zarnescu, O.; Mazare, A.; Schmuki, P.; Cimpean, A. Lateral spacing of TiO2 nanotube coatings modulates in vivo early new bone formation. Biomimetics 2025, 10, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brammer, K.S.; Oh, S.; Cobb, C.J.; Bjursten, J.M.; van der Heyde, H.; Jin, S. Improved bone-forming functionality on diameter-controlled TiO2 nanotube surface. Acta Biomater. 2009, 8, 3215–3223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hengel, I.A.J.; Laçin, M.; Minneboo, M.; Fratila-Apachitei, L.E.; Apachitei, I.; Zadpoor, A.A. The effects of plasma electrolytically oxidized layers containing Sr and Ca on the osteogenic behavior of selective laser melted Ti6Al4V porous implants. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2021, 124, 112074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, X.; Liu, Y.; Xi, F.; Zhang, X.; Kang, Y. Micro-arc oxidation (MAO) and its potential for improving the performance of titanium implants in biomedical applications. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1282590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.J.; Fuh, L.J.; Chen, W.C. Nano-morphology, crystallinity and surface potential of anatase on micro-arc oxidized titanium affect its protein adsorption, cell proliferation and cell differentiation. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2020, 107, 110204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.J.; Fuh, L.J.; Chen, C.Y.; Chen, W.C.; Lin, J.H.C.; Chen, C.C. Rapid nano-scale surface modification on micro-arc oxidation coated titanium by microwave-assisted hydrothermal process. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2019, 95, 236–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hijazi, K.M.; Dixon, S.J.; Armstrong, J.E.; Rizkalla, A.S. Titanium alloy implants with lattice structures for mandibular reconstruction. Materials 2023, 17, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Distefano, F.; Pasta, S.; Epasto, G. Titanium lattice structures produced via additive manufacturing for a bone scaffold: A review. J. Funct. Biomater. 2023, 14, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Migita, S.; Tsushima, R.; Kishita, T.; Suyalatu. The impact of entrapped air bubbles on cell integration in porous metallic biomaterials. Biosurf. Biotribol. 2025, 11, e12091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; de Barros, N.R.; Zheng, T.; Gomez, A.; Doyle, M.; Zhu, J.; Nanda, H.S.; Li, X.; Khademhosseini, A.; Li, B. 3D printing and surface engineering of Ti6Al4V scaffolds for enhanced osseointegration in an in vitro study. Biomimetics 2024, 9, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, S.; Zhu, J.; Jing, Y.; He, S.; Cheng, L.; Shi, Z. A comprehensive review of surface modification techniques for enhancing the biocompatibility of 3D-printed titanium implants. Coatings 2023, 13, 1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaindl, R.; Homola, T.; Rastelli, A.; Schwarz, A.; Tarre, A.; Kopp, D.; Coclite, A.M.; Görtler, M.; Meier, B.; Prettenthaler, B.; et al. Atomic layer deposition of oxide coatings on porous metal and polymer structures fabricated by additive manufacturing methods (laser-based powder bed fusion, material extrusion, material jetting). Surf. Interfaces 2022, 34, 102361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Wong, J.K.U.; Xia, Y.; Bilek, M.; Yeo, G.; Akhavan, B. Surface biofunctionalised porous materials: Advances, challenges, and future prospects. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2025, 154, 101518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmati, M.; Silva, E.A.; Reseland, J.E.; Heyward, C.A.; Haugen, H.J. Biological responses to physicochemical properties of biomaterial surface. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49, 5178–5224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Chen, J.; Huang, N. The structure, formation, and effect of plasma protein layer on the blood contact materials: A review. Biosurf. Biotribol. 2022, 8, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.S.; Kumbar, S.G.; Nukavarapu, S.P. Biomaterial-directed cell behavior for tissue engineering. Curr. Opn. Biomed. Eng. 2021, 17, 100260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayordomo, N.M.; Zatarain-Beraza, A.; Valerio, F.; Álvarez-Méndez, V.; Turegano, P.; Herranz-García, L.; de Aguileta, A.L.; Cattani, N.; Álvarez-Alonso, A.; Fanarraga, M.L. The protein corona paradox: Challenges in achieving true biomimetics in nanomedicines. Biomimetics 2025, 10, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salthouse, D.; Novakovic, K.; Hilkens, C.M.U.; Ferreira, A.M. Interplay between biomaterials and the immune system: Challenges and opportunities in regenerative medicine. Acta Biomater. 2023, 155, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnicer-Lombarte, A.; Chen, S.T.; Maliaras, G.G.; Barone, D.G. Foreign body reaction to implanted biomaterials and its impact in nerve neuroprosthetics. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 622524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loebel, C.; Mauck, R.; Burdick, J.A. Local nascent protein deposition and remodelling guide mesenchymal stromal cell mechanosensing and fate in three-dimensional hydrogels. Nat. Mater. 2019, 18, 883–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latour, R.A. Fundamental principles of the thermodynamics and kinetics of protein adsorption to material surfaces. Colloids Surf. B 2020, 191, 110992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrie, T.A.; Raynor, J.E.; Dumbauld, D.W.; Lee, T.T.; Jagtap, S.; Templeman, K.L.; Collard, D.M.; García, A.J. Multivalent integrin-specific ligands enhance tissue healing and biomaterial integration. Sci. Transl. Med. 2010, 2, 45ra60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, M.N.; Tran, S.D.; Abughanam, G.; Laurenti, M.; Zuanazzi, D.; Mezour, M.A.; Xiao, Y.; Cerruti, M.; Siqueira, W.L.; Tamimi, F. Biomaterial surface proteomic signature determines interaction with epithelial cells. Acta Biomater. 2017, 54, 150–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Mofrad, M.R.K.; Tepole, A.B. On modeling the multiscale mechanobiology of soft tissues: Challenges and progress. Biophys. Rev. 2022, 3, 031303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kersey, A.L.; Nguyen, T.U.; Nayak, B.; Singh, I.; Gaharwar, A.K. Omics-based approaches to guide the design of biomaterials. Mater. Today 2023, 64, 98–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Grrett, A.; Bose, S.; Blocker, S.; Rios, A.C.; Clevers, H.; Shen, X. The frontier of live tissue imaging across space and time. Cell Stem Cell 2021, 28, 603–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, C.D.G.; Alejo-Jacuinde, G.; Sanchez, B.P.; Reyes, J.C.; Onigbinde, S.; Mogut, D.; Hernández-Jasso, I.; Calderón-Vallejo, D.; Quintanar, J.L.; Mechref, Y. Multi omics application in biological systems. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2024, 46, 5777–5793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raabe, D.; Tasan, C.C.; Olivetti, E.A. Strategies for improving the sustainability of structural metals. Nature 2019, 575, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiśniewska, P.; Saeb, M.R.; Bencherif, S.A. Biomaterials recycling: A promising pathway to sustainability. Front. Biomater. Sci. 2023, 2, 1260402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panahi, O. Innovative Biomaterials for Sustainable Medical Implants: A Circular Economy Approach. Eur. J. Innov. Stud. Sustain. 2025, 1, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vyas, J.; Raytthatha, N.; Singh, S.; Prajapati, B.G.; Mohite, P.; Munde, S. Sustainable sources of raw materials as substituting biomaterials for additive manufacturing of dental implants: A review. Periodontal Implant Res. 2024, 8, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putra, N.E.; Zhou, J.; Zadpoor, A.A. Sustainable sources of raw materials for additive manufacturing of bone-substituting biomaterials. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2023, 13, 2301837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholap, S.S.; Kale, K.B. Optimization and analysis of sustainable magnesium-based alloy (Mg-Zn-Ca-Y) for biomedical applications. J. Alloys Metall. Syst. 2024, 6, 100068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radwan-Pragłowska, J.; Legutko, K.; Janus, Ł.; Sierkowska-Byczek, A.; Kuźmiak, K.; Radwan-Pragłowskaet, N. Electrochemical surface modification of fully biodegradable Mg-based biomaterials as a sustainable alternative to non-resorbable bone implants. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Materials | εr | PZC | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| SiO2 | 3.9–4.6 | 2.0–4.6 | [29,44,45,46] |

| Al2O3 | 9.0–11.5 | 6.8–9.9 | [29,44,46,47] |

| Cr2O3 | 11.9–13.3 | 6.0 | [29,45,46] |

| Fe2O3 | 12–16 | 7.1–9.2 | [29,45,46] |

| TiO2 (anatase) | 40–55 | 5.5–6.5 | [29,42] |

| TiO2 (rutile) | 80–170 | 3.6–4.4 | [29,42,45,46] |

| H2O | 79.6 | – | [46] |

| Materials | Thickness (nm) | Oxide/Chemical Composition | Interfacial Features | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ti | 3–7 | Mainly TiO2 (anatase/rutile) | Stable hydration layer in water; readily adsorbs Ca2+, PO43−, H+; hydroxyl density/acidity tunes protein secondary structure and motif exposure; crystal phase controls acid–base equilibrium/PZC; pH controls BSA coverage/orientation | [43,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60] |

| SUS316L | 1–3 | Cr2O3-rich passive film with Fe(III) oxides | Outermost monolayers are water- and hydroxyl-rich | [61,62] |

| Co-Cr-Mo | 2.5–3 | Cr(III) oxide (Cr2O3) with a smaller amount of Cr(III) hydroxide (Cr(OH)3) | Surface contains a large amount of OH− (hydrated/oxyhydroxide character) | [63,64] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Migita, S.; Sato, M. Protein Adsorption and Cell Adhesion on Metallic Biomaterial Surfaces. Adhesives 2025, 1, 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/adhesives1040015

Migita S, Sato M. Protein Adsorption and Cell Adhesion on Metallic Biomaterial Surfaces. Adhesives. 2025; 1(4):15. https://doi.org/10.3390/adhesives1040015

Chicago/Turabian StyleMigita, Satoshi, and Masaki Sato. 2025. "Protein Adsorption and Cell Adhesion on Metallic Biomaterial Surfaces" Adhesives 1, no. 4: 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/adhesives1040015

APA StyleMigita, S., & Sato, M. (2025). Protein Adsorption and Cell Adhesion on Metallic Biomaterial Surfaces. Adhesives, 1(4), 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/adhesives1040015