Conservancies: A Demonstrable Local-Level Action for the Sustainable Development Goals in an African Indigenous Frontier †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

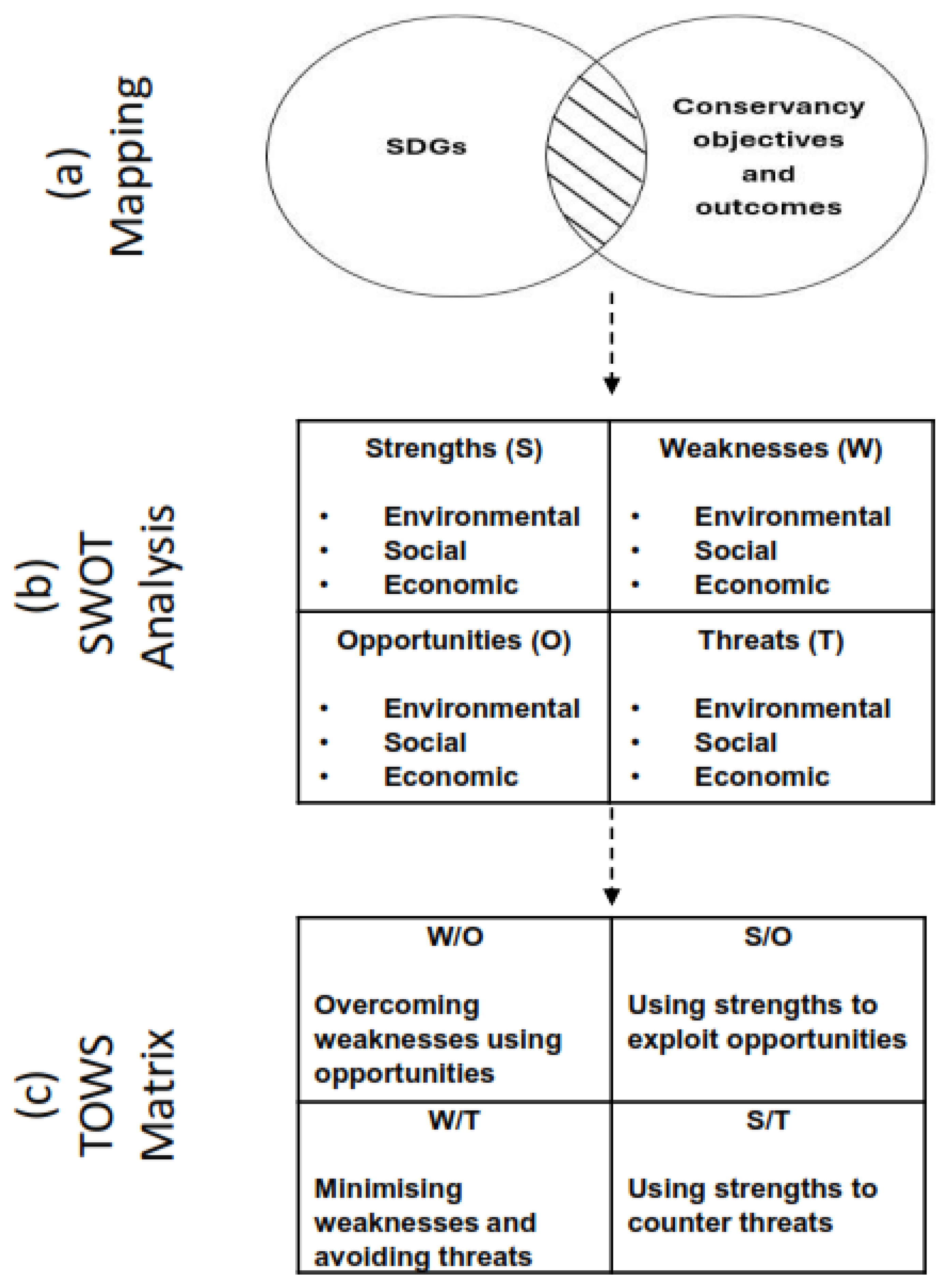

2.1. Analytical Framework

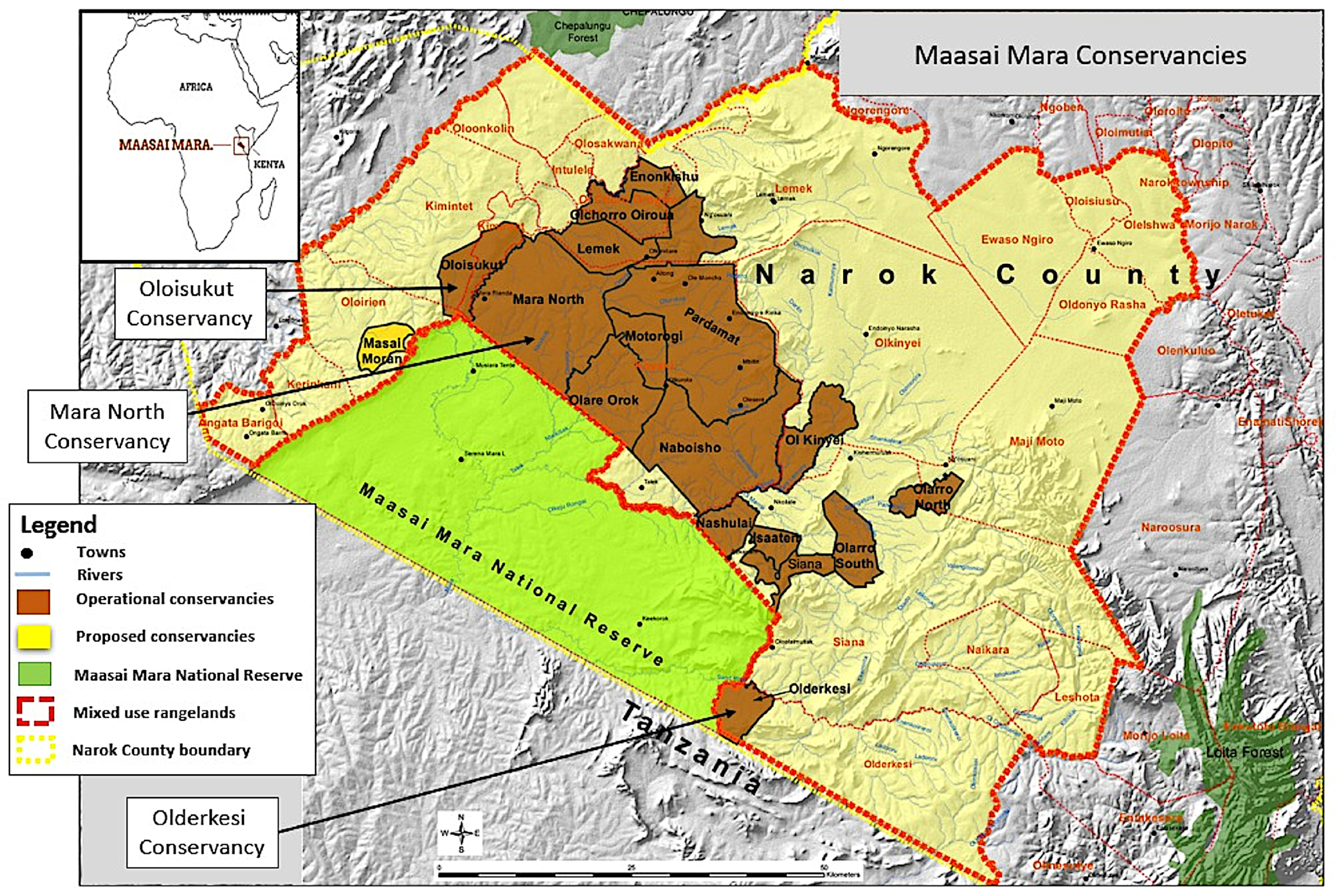

2.2. Study Site

2.3. Data Collection and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. How Relevant SDGs Are Addressed by Conservancies

3.2. SWOT Analysis

3.3. TOWS Analysis

4. Discussion

- (i)

- Strengthening local governance systems—Strengthening of conservancy governance can be usefully directed not only at improving their technical and administrative capacities, but also at embedding core principles of inclusivity, equity, transparency, and accountability within their institutional and operational frameworks. Efforts at empowering women by including them in conservancy management should be bolstered with initiatives that critically challenge social norms. Environmental education to reinforce existing cultural and environmental values in order to enhance collective action should be incorporated in conservancy capacity building. Development partners, especially the government, should also commit to providing sustained, long-term financial support to conservancies.

- (ii)

- Diversification of revenue streams—Conservancies need to broaden their income sources to enhance resilience and minimize risk and vulnerability. This may include promoting alternative payments for ecosystem services (e.g., carbon credits) and developing nature-based enterprises such as eco-certification and niche marketing of natural products like honey, resins, and medicinal plants.

- (iii)

- Reducing resource dependence—Conservancies need to pursue strategies to alleviate resource dependence in the long term, e.g., livestock destocking through the introduction of higher-quality breeds, in order to enhance the capacity of local communities to participate in conservation.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AGM | Annual General Meeting |

| CBNRM | Community-Based Natural Resource Management |

| HWC | Human wildlife conflict |

| KES | Kenya Shillings |

| NGOs | Non-governmental organizations |

| PES | Payment for Ecosystem Services |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| SWOT | Strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats |

| TOWS | Threats, opportunities, weaknesses and strengths |

| USD | United States Dollar |

| USAID | United States Agency for International Development |

References

- UN. Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. RES/70/1, Resolution Adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2015. 2015. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/ (accessed on 3 April 2020).

- Annan-Aggrey, E.; Kyeremeh, E.; Kutor, S.; Atuoye, K. Harnessing ‘communities of practice’ for local development and advancing the Sustainable Development Goals. Afr. Geogr. Rev. 2022, 41, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, J.D.; Lafortune, G.; Fuller, G.; Iablonovski, G. Financing Sustainable Development to 2030 and Mid-Century. Sustainable Development Report 2025; SDSN: Paris, France; Dublin University Press: Dublin, Ireland, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sever, S.D.; Tok, E.; Sellami, A.L. Sustainable Development Goals in a Transforming World: Understanding the Dynamics of Localization. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satterthwaite, D. Who can implement the sustainable development goals in urban areas? In Urban Planet: Knowledge towards Sustainable Cities; Thomas, E., Xuemei, B., Niki, F., Corrie, G., David, M., Timon, M., Susan, P., Patricia, R., David, S., Mark, W., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018; pp. 408–410. [Google Scholar]

- Satterthwaite, D. Where are the Local Indicators for the SDGs. Blog of the IIED. 2016. Available online: https://www.iied.org/where-are-local-indicators-for-sdgs (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Palmer, D.; Fricska, S.; Wehrmann, B. Towards Improved Land Governance; Land Tenure Working Paper 11; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO): Rome, Italy, 2009; p. 781. [Google Scholar]

- Ndugwa, R.P.; Omusula, C.K. Institutional Frameworks, Policies, and Land Data: Insights from Monitoring Land Governance and Tenure Security in the Context of Sustainable Development Goals in Kenya, Rwanda, Uganda, and Zambia. Land 2025, 14, 960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.F.; Sánchez-Hernández, M.I.; Carvalho, L.C. Local public administration in the process of implementing sustainable development goals. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesso, T.; Nzengya, D. The role of local governments in localizing and implementing the SDGs: A systematic review of challenges and opportunities in the Sub-Saharan context. Afr. Multidiscip. J. Res. 2023, 1, 366–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, A.; Mc Guinness, S.; Murphy, E.; Kelliher, G.; Hagin-Meade, L. Priorities, scale and insights: Opportunities and challenges for community involvement in SDG implementation and monitoring. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Aceituno, A.; Peterson, G.D.; Norström, A.V.; Wong, G.Y.; Downing, A.S. Local lens for SDG implementation: Lessons from bottom-up approaches in Africa. Sustain. Sci. 2020, 15, 729–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmail, N.; McPherson, J.M.; Abulu, L.; Amend, T.; Amit, R.; Bhatia, S.; Bikaba, D.; Brichieri-Colombi, T.A.; Brown, J.; Buschman, V. What’s on the horizon for community-based conservation? Emerging threats and opportunities. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2023, 38, 666–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozaki, Y.; Shaw, R. Citizens’ social participation to implement sustainable development goals (SDGs): A literature review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ningrum, D.; Malekpour, S.; Raven, R.; Moallemi, E.A.; Bonar, G. Three perspectives on enabling local actions for the sustainable development goals (SDGs). Glob. Sustain. 2024, 7, e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, F.; Muyamwa-Mupeta, P.; Muyengwa, S.; Sulle, E.; Kaelo, D. Progress or regression? Institutional evolutions of community-based conservation in eastern and southern Africa. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 2021, 3, e302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, L.W.; Eba, B.; Flintan, F.; Frija, A.; Nganga, I.N.; Ontiri, E.M.; Sghaier, M.; Abdu, N.H.; Moiko, S.S. The Challenges of Community-Based Natural Resource Management in Pastoral Rangelands. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2021, 34, 1213–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roe, D.; Nelson, F. The origins and evolution of community-based natural resource management in Africa. In Community Management of Natural Resources in Africa: Impacts, Experiences and Future Directions; Dilys, R., Nelson, F., Sandbrook, C., Eds.; International Institute for Environment and Development: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Roe, D.; Nelson, F.; Sandbrook, C. (Eds.) Community Management of Natural Resources in Africa: Impacts, Experiences and Future Directions; International Institute for Environment and Development: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, L.A.; Avery, K.; Borgerhoff Mulder, M.; Gohil, D.; King, J.; Lalampaa, T.; Letaapo, T.; Moiko, S.S.; Njeru Njagi, T.; Ontiri, E.M. Supporting Community-Based Natural Resource Management in Pastoralist Societies in East Africa to Achieve the UN Sustainable Development Goals; University of Exeter: Exeter, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- KWCA. State of Wildlife Conservancies in Kenya Report; Kenya Wildlife Conservancies Association: Nairobi, Kenya, 2016; Available online: https://kwcakenya.com/download-category/publications/ (accessed on 16 January 2018).

- Oduor, A.M. Livelihood impacts and governance processes of community-based wildlife conservation in Maasai Mara ecosystem, Kenya. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 260, 110133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedelian, C.; Ogutu, J.O. Trade-offs for climate-resilient pastoral livelihoods in wildlife conservancies in the Mara ecosystem, Kenya. Pastoralism 2017, 7, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, D.M.; Serneels, S.; Kaelo, D.O.; Trench, P.C. Maasai Mara—Land privatization and wildlife decline: Can conservation pay its way? In Staying Maasai? Livelihoods, Conservation and Development in East African Rangelands; Homewood, K., Kristjanson, P., Trench, P.C., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 77–114. [Google Scholar]

- Homewood, K.; Kristjanson, P.; Trench, P.C. Changing land use, livelihoods and wildlife conservation in Maasailand. In Staying Maasai? Livelihoods, Conservation and Development in East African Rangelands; Homewood, K., Kristjanson, P., Trench, P.C., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 1–42. [Google Scholar]

- Bashir, M.A.; Wanyonyi, E. Winning space for conservation: The growth of wildlife conservancies in Kenya. Front. Conserv. Sci. 2024, 5, 1385959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KWCA. Strategic Plan 2019-2024; Kenya Wildlife Conservancies Association: Nairobi, Kenya, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Western, D.; Waithaka, J.; Kamanga, J. Finding space for wildlife beyond national parks and reducing conflict through community-based conservation: The Kenya experience. Parks 2015, 21, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leigh, D. SWOT Analysis. In Handbook of Improving Performance in the Workplace: Selecting and Implementing Performance Interventions; Ryan, W., Doug, L., Eds.; Pfeifer: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2009; Volume 3, pp. 115–140. [Google Scholar]

- Sammut-Bonnici, T.; Galea, D. SWOT Analysis. In Wiley Encyclopedia of Management; Cooper, C.L., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; Volume 12, pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- MMWCA. State of the Mara Conservancies; Maasai Mara Wildlife Conservancies Association: Narok, Kenya, 2019; Available online: https://maraconservancies.org/resources/ (accessed on 15 January 2020).

- NCG. Narok County Integrated Development Plan 2018–2022; County Government of Narok: Narok, Kenya, 2018. Available online: https://narok.go.ke/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/NAROK-CIDP-2018-2022.pdf (accessed on 11 March 2020).

- NCG. Greater Maasai Mara Ecosystem Management Plan, 2023–2032; County Government of Narok: Narok, Kenya, 2023. Available online: https://narok.go.ke/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/GMME-Management-Plan-200320238_compressed.pdf (accessed on 9 March 2024).

- Thompson, M.; Homewood, K. Entrepreneurs, elites, and exclusion in Maasailand: Trends in wildlife conservation and pastoralist development. Human. Ecol. 2002, 30, 107–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedelian, C. Conservation and Ecotourism on Privatised Land in the Mara, Kenya: The Case of Conservancy Land Leases; Working Paper No. 9; The Land Deal Politics Initiative: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Løvschal, M.; Håkonsson, D.D.; Amoke, I. Are goats the new elephants in the room? Changing land-use strategies in Greater Mara, Kenya. Land Use Policy 2019, 80, 395–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galaty, J.G. “The land is yours”: Social and economic factors in the privatization, sub-division and sale of Maasai ranches. Nomad. Peopl. 1992, 30, 26–40. [Google Scholar]

- Tarayia, G.N. The legal perspectives of the Maasai culture, customs, and traditions. Ariz. J. Int’l Comp. L. 2004, 21, 183. [Google Scholar]

- Keane, A.; Gurd, H.; Kaelo, D.; Said, M.Y.; de Leeuw, J.; Rowcliffe, J.M.; Homewood, K. Gender differentiated preferences for a community-based conservation initiative. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0152432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weldemichel, T.; Lein, H. Land Division, Conservancies, Fencing and Its Implications in the Maasai Mara, Kenya; WP 5.2: Policy Analysis, AfricanBioServices; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lamprey, R.H.; Reid, R.S. Expansion of human settlement in Kenya’s Maasai Mara: What future for pastoralism and wildlife? J. Biogeogr. 2004, 31, 997–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MMWCA. Maasai Mara Wildlife Conservancies Association: Strategic Plan 2017–2020; Maasai Mara Wildlife Conservancies Association: Narok, Kenya, 2017; Available online: https://maraconservancies.org/resources/ (accessed on 20 April 2019).

- KWCA. Maasai Mara Conservancies. Kenya Wildlife Conservancies Association. (n.d.). Available online: https://kwcakenya.com/ (accessed on 18 July 2020).

- Shenton, A.K. Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Educ. Inf. 2004, 22, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osano, P.M.; Said, M.Y.; de Leeuw, J.; Ndiwa, N.; Kaelo, D.; Schomers, S.; Birner, R.; Ogutu, J.O. Why keep lions instead of livestock? Assessing wildlife tourism-based payment for ecosystem services involving herders in the Maasai Mara, Kenya. Proc. Nat. Resour. Forum 2013, 37, 242–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MMWCA. A Thriving Landscape: A Decade of Transforming Community Conservation in the Maasai Mara. An Impact Report. Maasai Mara Wildlife Conservancies Association: Narok, Kenya, 2023. Available online: https://maraconservancies.org/resources/ (accessed on 11 February 2024).

- Osano, P.M.; Said, M.Y.; de Leeuw, J.; Moiko, S.S.; Ole Kaelo, D.; Schomers, S.; Birner, R.; Ogutu, J.O. Pastoralism and ecosystem-based adaptation in Kenyan Masailand. Int. J. Clim. Change Strateg. Manag. 2013, 5, 198–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyrrell, P.; Evans, L.; Brehony, P.; Wood, P.; Karimi, R.; Ole Kaelo, D.; Hunter, F.; Muiyuro, R.; Kang’ethe, E.; Perry, B. Bridging the conservation and development trade-off? A working landscape critique of a conservancy in the Maasai Mara. Ecol. Solut. Evid. 2024, 5, e12369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mureithi, S.M.; Verdoodt, A.; Njoka, J.T.; Gachene, C.K.; Warinwa, F.; Van Ranst, E. Impact of community conservation management on herbaceous layer and soil nutrients in a Kenyan semi-arid savannah. Land Degrad. Dev. 2016, 27, 1820–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadupoi, P. Mara Conservancies Lead the Way in Biodiversity Conservation. In The Evolution of a Landscape: A Decade of Leading Community Conservation in the Maasai Mara; Voice of the Mara 8th Edition; Sopia, D., Nadupoi, P., Kereto, L.O., Eds.; MMWCA: Narok, Kenya, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bii, J. One Mara Carbon Project: Leveraging local knowledge to address climate change. In The Next Decade: The Impact of Community-Based Conservation in the Maasai Mara; Voice of the Mara 9th Edition; Peshut, W.M., Ed.; Maasai Mara Wildlife Conservancies Association: Narok, Kenya, 2024. [Google Scholar]

| SDGs | Examples of Corresponding Conservancy Goals and Outcomes |

|---|---|

| Goal 1: Ending poverty | Livelihood diversification and income supplementation; business enterprises development; employment; loan facilities; pastoral development; human–wildlife conflict compensation; trust funds for social protection |

| Goal 2: Ending hunger | Income for provision of food, livestock management, livestock market access, pasture management; compensation for livestock predation; income-generating activities such as honey production |

| Goal 3: Health and well-being | Investment in health facilities; provision of medicine and ambulance services. |

| Goal 4: Inclusive and equitable quality education | Investment in schools; provision of bursaries; employment of teachers; school-feeding programmes |

| Goal 5: Gender equality | Inclusion of women in conservancy committees; formation of women self-help groups; women income income-generating activities such as beadwork; bursaries for female children |

| Goal 6: Clean water | Water supply projects like water pans and boreholes, protection of natural water sources |

| Goal 7: Affordable and clean energy | Introduction of solar power, biogas projects, use of clean energy in tourist facilities |

| Goal 8: Inclusive and sustainable economic growth | Tourism enterprise development and employment opportunities |

| Goal 9: Resilient infrastructure | Infrastructure development such as roads, bridges, schools |

| Goal 10: Reduced inequalities | Financial flow from tourism and foreign aid; local participation in conservation decision making |

| Goal 11: Sustainable communities | Building social capital and cohesion; enhanced physical security; provision of social amenities and infrastructure; cultural preservation |

| Goal 12: Sustainable consumption and production | Controlled utilization of natural resources; low volume- high end tourism models; wildlife compatible livelihood activities such as rotational grazing and beekeeping; conservation education |

| Goal 13: Climate action | Restoration of grasslands and forests for carbon sequestration; climate change resilience building through livelihood diversification; participation in carbon markets; climate change awareness |

| Goal 15: Sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems | Ecotourism; rangelands and wildlife restoration and conservation; integration of ecosystem and biodiversity values in local land management plans; mobilization of financial resources for conservation; wildlife security measures |

| Goal 16: Strong institutions | Development of local institutions for participation in resource governance |

| Goal 17: Partnerships for the goals | Collaborations with the private sector, non-governmental organizations and government organisations from local to international levels; resource mobilization; capacity building |

| Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|

Environmental

| Environmental

|

| Opportunities | Threats |

Environmental

| Environmental

|

| TOWS Strategy | Proposed Action |

|---|---|

| WO (overcoming weakness using opportunities) |

|

| SO (using strengths to exploit opportunities) |

|

| ST (using strengths to counter threats) |

|

| WT (minimizing weaknesses and avoiding threats) |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Imbo, A.O.; Wehn, U.; Irvine, K. Conservancies: A Demonstrable Local-Level Action for the Sustainable Development Goals in an African Indigenous Frontier. Environ. Earth Sci. Proc. 2025, 36, 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/eesp2025036008

Imbo AO, Wehn U, Irvine K. Conservancies: A Demonstrable Local-Level Action for the Sustainable Development Goals in an African Indigenous Frontier. Environmental and Earth Sciences Proceedings. 2025; 36(1):8. https://doi.org/10.3390/eesp2025036008

Chicago/Turabian StyleImbo, Alexander Omondi, Uta Wehn, and Kenneth Irvine. 2025. "Conservancies: A Demonstrable Local-Level Action for the Sustainable Development Goals in an African Indigenous Frontier" Environmental and Earth Sciences Proceedings 36, no. 1: 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/eesp2025036008

APA StyleImbo, A. O., Wehn, U., & Irvine, K. (2025). Conservancies: A Demonstrable Local-Level Action for the Sustainable Development Goals in an African Indigenous Frontier. Environmental and Earth Sciences Proceedings, 36(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/eesp2025036008