The Study of the Urban Heat Island Effect in Cyprus for the Period 2013–2023 by Using Google Earth Engine †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- Surface Temperature: This refers to the temperature of the Earth’s surface, which can be measured using remote sensing technologies like satellites. It reflects how much heat is being absorbed or emitted by the ground, buildings, roads, and other surfaces in an urban area. Urban surfaces, such as asphalt or concrete, tend to absorb and retain more heat compared to natural land cover like vegetation or soil. This leads to higher surface temperatures in urban areas, contributing to the Urban Heat Island effect.

- Air Temperature: This refers to the temperature of the atmosphere at a particular height above ground (often at 1.5 m). It measures the warmth of the air that people experience and can be influenced by various factors such as wind, humidity, and the underlying surface. In cities, air temperatures are typically higher than in rural areas due to the heat retained by buildings and roads and the lack of vegetation to cool the air through evapotranspiration.

3. Results

4. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gluch, R.; Quattrochi, D.A.; Luvall, J.C. A multi-scale approach to urban thermal analysis. Remote Sens. Environ. 2006, 104, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjimitsis, D.G.; Retalis, A.; Michaelides, S.; Tymvios, F.; Paronis, D.; Themistocleous, K.; Agapiou, A. Satellite and ground measurements for studying the Urban Heat Island Effect in Cyprus. In Remote Sensing of Environment-Integrated Approaches, Chapter 1; Hadjimitsis, D., Ed.; InTech: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Cheng, J. Spatio-temporal analysis of urban heat island using multisource remote sensing data: A case study in Hangzhou, China. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2019, 12, 3317–3326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, G. Evaluating the roles of green and built-up areas in reducing a surface urban heat island using remote sensing data. Urbani Izziv 2019, 2, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecinati, F.; Amitrano, D.; Leoncio, L.B.; Walugendo, E.; Guida, R.; Iervolino, P.; Natarajan, S. Exploitation of ESA and NASA heritage remote sensing data for monitoring the heat island evolution in Chennai with the Google Earth Engine. In Proceedings of the IGARSS 2019–2019 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, Yokohama, Japan, 28 July–2 August 2019; pp. 6328–6331. [Google Scholar]

- Liebowitz, A.; Sebastian, E.; Yanos, C.; Bilik, M.; Blake, R.; Norouzi, H. Urban Heat Islands and Remote Sensing: Characterizing Land Surface Temperature at the Neighborhood Scale. In Proceedings of the IGARSS 2020–2020 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 26 September–2 October 2020; pp. 4407–4409. [Google Scholar]

- Li, N.; Li, X. The Impact of Building Thermal Anisotropy on Surface Urban Heat Island Intensity Estimation: An Observational Case Study in Beijing. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2020, 17, 2030–2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, Q.; Rajasekar, U.; Hu, X. Modeling Urban Heat Islands and their relationship with impervious surface and vegetation abundance by using ASTER images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2011, 49, 4080–4089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliades, M.; Michaelides, S.; Evagorou, E.; Fotiou, K.; Fragkos, K.; Leventis, G.; Theocharidis, C.; Panagiotou, C.F.; Mavrovouniotis, M.; Neophytides, S.; et al. Earth Observation in the EMMENA region: Scoping review of current applications and knowledge gaps. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 4202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorelick, N.; Hancher, M.; Dixon, M.; Ilyushchenko, S.; Thau, D.; Moore, R. Google Earth Engine: Planetary-scale geospatial analysis for everyone. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 202, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oke, T.R. The energetic basis of the urban heat island. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 1982, 108, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voogt, B.; Oke, T. Thermal remote sensing of urban climates. Remote Sens. Environ. 2003, 86, 370–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imhoff, M.L.; Zhang, P.; Wolfe, R.E.; Bounoua, L. Remote sensing of the urban heat island effect across biomes in the continental USA. Remote Sens. Environ. 2010, 114, 504–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

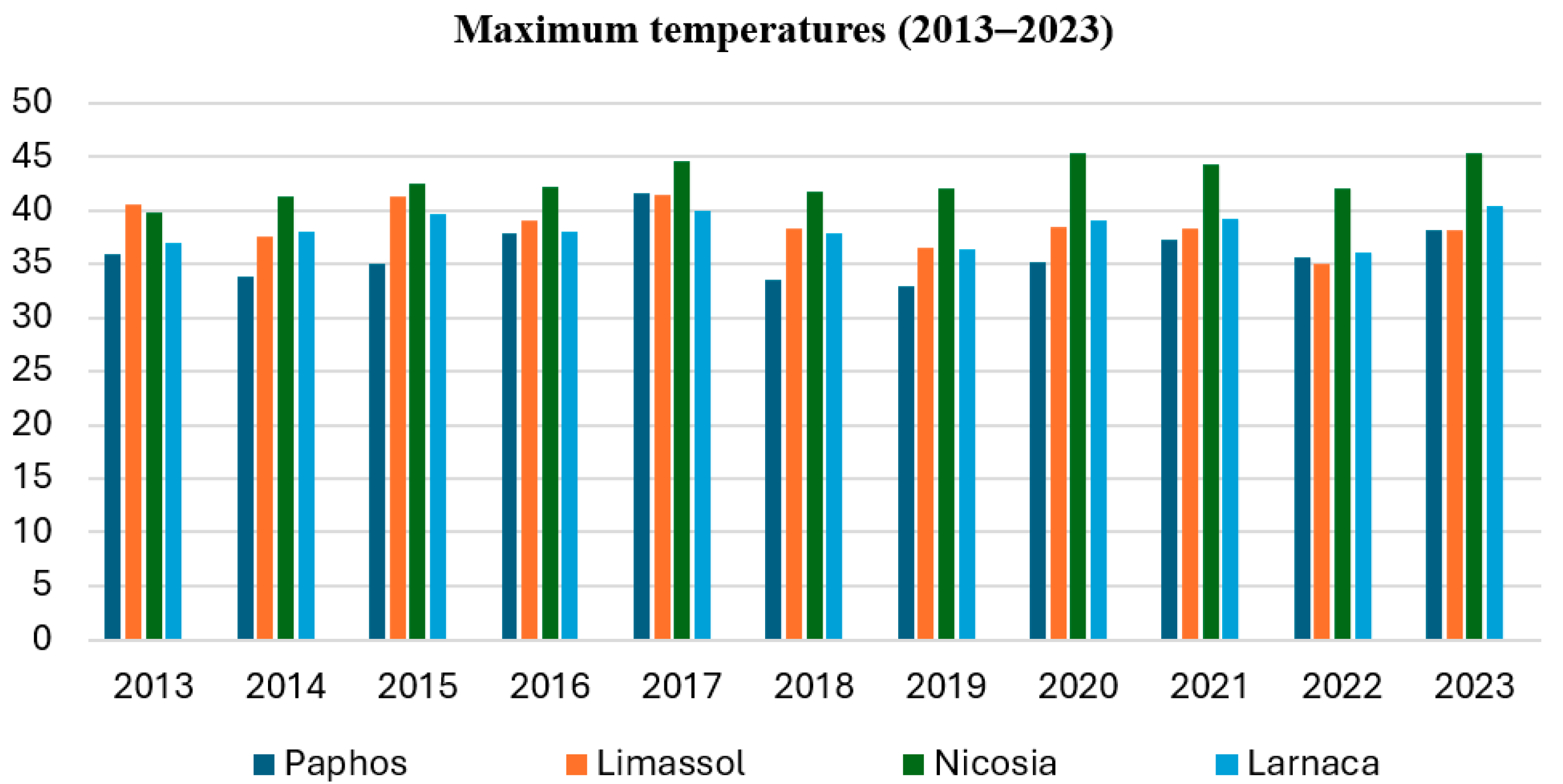

| Year | Pafos | Limassol | Nicosia | Larnaca | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature | Date | Temperature | Date | Temperature | Date | Temperature | Date | |

| 2023 | 38.1 | 24/7 | 38.2 | 24/7 | 45.3 | 14/8 | 40.4 | 24/7 |

| 2022 | 35.6 | 22/6 | 35.1 | 19/7 | 42 | 28/7 | 36.1 | 18/7 |

| 2021 | 37.3 | 28/7 | 38.3 | 16/7 | 44.3 | 4/8 | 39.2 | 6/8 |

| 2020 | 35.2 | 22/8 | 38.5 | 31/8 | 45.3 | 4/9 | 39.1 | 31/8 |

| 2019 | 33 | 8/8 | 36.6 | 3/6 | 42.1 | 25/6 | 36.4 | 21/7 |

| 2018 | 33.5 | 5/7 | 38.3 | 23/7 | 41.7 | 14/8 | 37.8 | 6/7 |

| 2017 | 41.6 | 1/7 | 41.4 | 2/7 | 44.6 | 2/7 | 39.9 | 1/7 |

| 2016 | 37.8 | 17/6 | 39.1 | 20/6 | 42.2 | 23/6 | 38 | 20/6 |

| 2015 | 35 | 3/8 | 41.3 | 4/8 | 42.5 | 3/8 | 39.6 | 3/8 |

| 2014 | 33.8 | 24/8 | 37.5 | 24/8 | 41.3 | 28/6 | 38 | 28/6 |

| 2013 | 36 | 19/6 | 40.5 | 17/6 | 39.8 | 15/8 | 37 | 17/8 |

| 2012 | 35.6 | 18/7 | 39.5 | 6/8 | 43.6 | 17/7 | 38.5 | 7/8 |

| 2011 | 34.8 | 27/7 | 38 | 10/6 | 41.3 | 9/8 | 37.1 | 17/7 |

| 2010 | 35.2 | 17/6 | 39.6 | 18/8 | 45.6 | 1/8 | 38.6 | 2/8 |

| Pearson | Spearman | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FVC-UHI | FVC-UTFVI | FVC-UHI | FVC-UTFVI | |

| Rural areas | −0.446 | −0.382 | −0.391 | −0.372 |

| City centre | −0.287 | −0.214 | −0.581 | −0.214 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Soteriades, C.; Michaelides, S.; Hadjimitsis, D. The Study of the Urban Heat Island Effect in Cyprus for the Period 2013–2023 by Using Google Earth Engine. Environ. Earth Sci. Proc. 2025, 35, 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/eesp2025035080

Soteriades C, Michaelides S, Hadjimitsis D. The Study of the Urban Heat Island Effect in Cyprus for the Period 2013–2023 by Using Google Earth Engine. Environmental and Earth Sciences Proceedings. 2025; 35(1):80. https://doi.org/10.3390/eesp2025035080

Chicago/Turabian StyleSoteriades, Charalampos, Silas Michaelides, and Diofantos Hadjimitsis. 2025. "The Study of the Urban Heat Island Effect in Cyprus for the Period 2013–2023 by Using Google Earth Engine" Environmental and Earth Sciences Proceedings 35, no. 1: 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/eesp2025035080

APA StyleSoteriades, C., Michaelides, S., & Hadjimitsis, D. (2025). The Study of the Urban Heat Island Effect in Cyprus for the Period 2013–2023 by Using Google Earth Engine. Environmental and Earth Sciences Proceedings, 35(1), 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/eesp2025035080