Abstract

The fashion industry, despite its global economic importance, is a major contributor to environmental degradation and social inequality. In response, sustainable fashion has emerged as a growing movement advocating ethical, ecological, and socially responsible practices. This study presents a comprehensive bibliometric analysis of 1134 peer-reviewed journal articles on sustainable fashion indexed in Scopus from 1986 to 2025. Results show an exponential rise in research output after 2015, with interdisciplinary contributions from social sciences, business, environmental science, and engineering. By applying performance analysis and science mapping techniques, the study identifies five major research themes: “Consumer Behavior,” “Design Ethics,” “Circular Economy,” “Innovation,” and “Digital Media.” The geographic distribution reveals strong outputs from both developed and emerging economies. This study provides an integrative overview of the intellectual landscape of sustainable fashion and serves as a roadmap for researchers, policymakers, and practitioners who are interested in the development of sustainable fashion.

1. Introduction

Fashion shapes trends, influences consumer lifestyles, and generates trillions in revenue annually [1]. However, its meteoric growth and fast-paced dynamics conceal a far-reaching environmental footprint. Often referred to as one of the most polluting industries, fashion is implicated in numerous ecological issues, including excessive water and energy use, high greenhouse gas emissions, chemical pollution, and waste generation [2]. The global fashion industry is responsible for around 10% of total carbon dioxide emissions and consumes more water than any other industry aside from agriculture [3]. Washing synthetic fabrics annually releases over half a million tons of plastic microfibers into the ocean, which is the same as more than 50 billion plastic bottles [4].

A major driver of this environmental crisis is the fast fashion consumption model [5]. Fast fashion is defined by rapid production cycles, low-cost garments, and a relentless push to replicate trends and introduce new collections at high frequency [6]. This approach not only fuels overproduction and overconsumption, but also generates vast quantities of textile waste, as garments are often discarded after only a few uses [7]. The lifecycle of fast fashion is short and linear, moving quickly from production to consumption to disposal, which makes it inherently unsustainable. This accelerates problems such as landfill overflow, the release of toxic chemicals, and the proliferation of unethical labor practices [2]. The social consequences are equally alarming, with labor rights violations, unsafe working conditions, and exploitative wages continuing to plague garment factories, particularly in developing countries [8].

In response to these growing concerns, sustainable fashion has emerged as a promising and necessary alternative [9]. Sustainable fashion, also referred to interchangeably as ethical fashion, green fashion, slow fashion, and eco-fashion, advocates for an industry grounded in environmental conservation, social justice, and long-term financial sustainability [10]. It encompasses a wide array of practices, including the use of organic and biodegradable materials, energy-efficient production processes, fair trade certification, transparency in supply chains, and consumer education on conscious purchasing [11]. Importantly, sustainable fashion promotes a shift from quantity to quality, encouraging consumers to buy less but better, and to value durability, repairability, and recyclability in clothing [12].

Globally, the sustainable fashion movement is gaining traction, though its adoption remains uneven across regions and market segments [13]. In developed countries, particularly in Europe and North America, sustainable fashion has made significant inroads through policy initiatives, consumer advocacy, and corporate responsibility programs [14]. The European Union, for instance, has launched the Circular Economy Action Plan, which includes measures targeting textiles as a priority sector [15]. Leading fashion brands have introduced eco-conscious lines, increased the use of recycled materials, and implemented take-back schemes [16].

The growing discourse on sustainability in fashion has sparked academic interest across a wide range of disciplines, including environmental science, economics, marketing, sociology, design, and political science [17]. This cross-disciplinary engagement underscores the complex and multifaceted challenges that sustainability presents within the fashion sector [11]. Some existing reviews have examined specific aspects of sustainable fashion, such as consumer behavior [18], designer’s contributions [19] marketing [20], retailing [21], supply chain management [22], and sustainability [23], but comprehensive and data-driven syntheses of the broader intellectual landscape remain limited. Therefore, this study seeks to explore and map the contours of scholarly research on sustainable fashion through a bibliometric analysis. Specifically, it aims to examine major publication trends, research patterns, and thematic structures that have emerged over the past two decades. Using co-occurrence, co-citation, bibliographic coupling, and co-authorship analysis, the study endeavors to uncover the intellectual foundations, collaborative dynamics, and emerging hotspots of knowledge production in the domain of sustainable fashion.

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Research Field of Sustainable Fashion

The concept of sustainable fashion has undergone a significant transformation over the past two decades, evolving from a marginal, eco-conscious niche into a prominent research domain and commercial priority [9,24]. This shift is grounded in growing awareness of the environmental degradation and social injustices associated with the conventional fashion industry, particularly the fast fashion model [5]. By the 2010s, sustainable fashion had gained increasing recognition as a legitimate field of inquiry, propelled by parallel developments in environmental activism, ethical consumerism, and global policy discourse [14]. The conversation around sustainable fashion gradually expanded to incorporate broader theoretical frameworks, such as the triple bottom line, circular economy, life cycle thinking, and cradle-to-cradle design [11]. As a result, sustainable fashion came to be viewed not merely as a critique of fast fashion, but as a constructive alternative that is design-led, innovation-driven, and socially responsible, with the aim of reconciling style with sustainability [25].

Significantly, the evolution of the field reflects shifts not only in discourse but also in practice [26]. Design thinking and sustainability became central to curricula in fashion schools, and major fashion brands began adopting sustainability-oriented innovations [13,17]. Examples include the use of recycled fibers, organic cotton, plant-based dyes, waterless dyeing technologies, and modular or convertible garment design [26,27]. At the same time, the fashion industry began engaging with sustainability reporting, aligning with standards such as the Global Reporting Initiative and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals [28].

Building on these developments, the scholarly literature in sustainable fashion is diverse but can be broadly categorized into five key research streams:

- Environmental Sustainability: This stream focuses on the environmental impacts of fashion production and consumption, examining topics such as water and energy use, carbon emissions, pollution, and waste management. Researchers investigate life cycle assessment of garments, biodegradable materials, and the use of renewable resources in textile production [24]. Studies also explore ecological indicators, circular economy frameworks, and the integration of environmental sustainability in fashion design and policy [2]. This stream provides an understanding of the ecological footprint of fashion and the mitigation strategies required to reduce it [3].

- Production and Supply Chain, Including Materials and Design: This stream covers sustainable production processes, ethical sourcing, labor rights, and innovations in fashion design. Research addresses issues such as supply chain transparency, traceability, and the adoption of certifications (e.g., Global Organic Textile Standard, Fair Trade) [22]. It also includes design-based strategies like zero-waste pattern cutting, modular design, and the use of innovative eco-materials [26]. This research stream examines the role of design thinking and technological innovation in transforming production models and fostering sustainability from the earliest stages of product development [25].

- Retail and Marketing: Research in this stream investigates how sustainable fashion is positioned, promoted, and perceived in the marketplace [29]. Topics include green branding, corporate social responsibility communications, marketing ethics, and the effectiveness of sustainability labels [30]. Scholars also examine retail formats, digital platforms, and social media campaigns that support or hinder the adoption of sustainable products [13]. This stream highlights the commercial and strategic aspects of promoting sustainability in a competitive fashion market [14].

- Consumer Psychology and Behaviors: This stream explores consumer attitudes, values, motivations, and behavioral intentions related to sustainable fashion [31]. Theoretical frameworks, such as the Theory of Planned Behavior [32], are frequently employed. Research focuses on factors influencing purchasing decisions, such as environmental concern, ethical beliefs, price sensitivity, social norms, and perceived consumer effectiveness [33]. It also investigates the barriers to sustainable behavior, including the widely observed attitude–behavior gap [34].

- Policy and Socioeconomic Implications: This stream examines the role of governmental and institutional frameworks in promoting sustainable practices within the fashion industry [35]. Topics include policy instruments, regulatory approaches, economic incentives, and international cooperation on sustainability standards [15]. Research also explores the socioeconomic dimensions of sustainable fashion, including labor conditions, community development, and social equity [36]. This stream situates sustainable fashion within broader discussions of development, governance, and global justice.

The above literature groups reflect major streams of research inquiry observed across the body of research, although they are not always explicitly labeled in individual studies. Rather, researchers often approach sustainable fashion through specific lenses such as technological innovation, consumer engagement, or corporate responsibility. These thematic categories are not mutually exclusive and frequently intersect in multidisciplinary studies. For instance, an investigation of sustainable supply chains may also address consumer transparency, digital tracking tools, and regulatory compliance [22,36]. The complexity and interconnectedness of sustainability challenges in fashion necessitate such integrative perspectives [2]. Recognizing these streams helps to structure the field conceptually, facilitating more systematic exploration and identification of patterns through bibliometric methods.

2.2. Previous Reviews of Sustainable Fashion Research

While the five key research areas help classify the broad scientific focus in sustainable fashion, authors tend to approach the field from a topical or technology-specific perspective rather than strictly aligning with these thematic categories. Numerous review papers have been published to consolidate findings on specific domains of sustainable fashion. For example, Busalim et al. [18] conducted a systematic review on sustainable consumption in fashion, offering insights into consumer motivations and barriers. Wang and Zakaria [19] explored how designers affected sustainable fashion. Ray and Nayak [20] reviewed the literature on sustainable fashion marketing. Yang et al. [21] examined sustainable retailing in the fashion industry. Köksal et al. [22] discussed the supply chain management in the textile industry. Daukantiene [23] examined the sustainability of global fashion industry, focusing on environmental, technological, and social implications. These reviews provide valuable syntheses but are often constrained by narrow scopes and selective literature inclusion.

These narrative reviews, while insightful, are subject to limitations in objectivity and comprehensiveness [37]. Their reliance on manual selection and thematic interpretation can introduce bias and limit reproducibility [38]. Furthermore, as the field has expanded rapidly, it has become increasingly difficult to capture the full breadth of research using traditional qualitative methods alone. The diversification of topics, methodologies, and disciplinary perspectives complicates efforts to draw generalizable conclusions or identify overarching patterns in the literature.

In response to these limitations, bibliometric approaches have gained prominence for their ability to systematically map research landscapes [39]. Bibliometric methods utilize quantitative data such as citation counts, co-authorship networks, and keyword frequencies to uncover structural trends, thematic clusters, and intellectual linkages [40]. Referring to the sustainable fashion, Özdil and Konuralp [41] applied bibliometric techniques to visualize the interplay between sustainability and fashion studies amidst the neoliberal era. Ruslan et al. [42] mapped some characteristics and patterns of sustainable fashion consumption in the Muslim context. Meanwhile, Prado et al. [43] reviews the sustainability issues in fashion retail.

However, bibliometric studies on sustainable fashion remain limited in number and exclusively focus on specific aspects or domains of sustainable fashion. As a result, existing bibliometric reviews provide fragmented insights and lack a comprehensive perspective on the evolution and structure of sustainable fashion research. Therefore, this situation calls for a comprehensive, macro-level bibliometric analysis that maps the emerging research themes and trends, intellectual structures and foundations, and global collaboration networks across the entire sustainable fashion field.

This study aims to fill the knowledge gap by offering a holistic bibliometric mapping of the sustainable fashion literature. To guide this endeavor, the following research questions are posed:

- (1)

- What are the main research themes in sustainable fashion, and how have these topics evolved over time?

- (2)

- What are the seminal foundations of sustainable fashion research, and how are they conceptually structured and organized within the field?

- (3)

- What are the key publication venues for disseminating sustainable fashion research, and how do these outlets shape scholarly discourse?

- (4)

- What are the geographic patterns of research output and collaboration, and how do these patterns influence the global development of sustainable fashion scholarship?

By providing answers to these questions, this study serves as a roadmap for scholars, practitioners, and policymakers by offering a systematic overview of the knowledge landscape of sustainable fashion. In doing so, it supports the advancement of a more coherent, collaborative, and impactful scholarly discourse, ultimately contributing to the transformation of sustainable fashion toward greater sustainability and social responsibility.

3. Methods

3.1. Data Source and Search Strategy

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) methodology is used in this study [44]. The PRISMA framework consists of four key phases: identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion. These steps guide the transparent and replicable retrieval and refinement of the bibliographic dataset.

- Identification: The Scopus database was selected as the primary data source due to its broad coverage of peer-reviewed journals across diverse academic disciplines, robust citation indexing capabilities, and widespread use in bibliometric research. Scopus is particularly suitable for capturing literature related to sustainability, business, environmental science, and social sciences, which are key domains intersecting with sustainable fashion. To retrieve relevant literature, a keyword-based search strategy was developed to reflect the multifaceted terminology commonly used in the field. The search string used in the Scopus query was: TITLE-ABS-KEY (“sustainable fashion” OR “ethical fashion” OR “eco-fashion” OR “slow fashion” OR “green fashion”). This query was designed to capture articles containing the relevant terms in their title, abstract, or keywords, yielding 1964 documents. The search was performed on 18 May 2025.

- Screening: To ensure data consistency and relevance, the following screening filters were applied: (1) source type limited to journals; and (2) document type restricted to journal articles. In addition, duplicate entries were identified and excluded by comparing document titles, DOIs, and associated metadata. No restrictions were placed on language or publication date. This inclusive approach enhances comprehensiveness and helps minimize selection bias, which is especially important in an interdisciplinary and globally oriented field such as sustainable fashion.

- Eligibility: After the initial screening, the remaining documents were reviewed for relevance based on their titles and abstracts. Only those with a substantive focus on sustainable fashion were deemed eligible, specifically studies that addressed environmental, ethical, economic, or policy-related aspects within the context of fashion. Articles that mentioned relevant keywords only in passing or in unrelated contexts were excluded during this stage.

- Inclusion: The final inclusion phase yielded 1134 articles that met all predefined criteria and were deemed suitable for bibliometric analysis.

3.2. Bibliometric Analysis and Visualization

The dataset was refined by standardizing spelling variations, consolidating synonymous terms, and ensuring consistency in phrasing. In addition, journal titles and volume/issue numbers were harmonized to enable accurate analysis of publication sources. This cleaned and standardized dataset provided a reliable base for generating bibliometric maps and calculating performance metrics.

The analytical scheme combines performance analysis and science mapping to provide a comprehensive overview of the field:

- Performance analysis was employed to assess basic publication metrics, including annual publication output, the most productive journals, leading authors, institutions, and countries. Citation-based indicators such as total citations and average citations per document were also examined to evaluate scholarly impact.

- Keyword co-occurrence analysis was conducted to identify the main research themes and conceptual structures within the field. Keywords were analyzed using fractional counting and a minimum occurrence threshold to generate thematic clusters. This method reveals the frequency and strength of keyword co-occurrences, helping to identify emerging topics and research hotspots.

- Co-citation analysis was applied to uncover the intellectual structure of the field by analyzing how often pairs of articles or authors are cited together. This approach enables the identification of seminal works and the core knowledge bases that underpin the field.

- Bibliographic coupling was used to explore the cognitive proximity among documents based on shared references. This technique highlights thematic similarities and connections between journals that contribute to knowledge dissemination.

- Co-authorship analysis examined collaborative relationships among countries. By mapping these networks, the study identified key international collaborations and assessed the extent of global research integration.

VOSviewer 1.6.20 was used to visualize relationships among various bibliometric items, including keywords, articles, sources, and authors, based on patterns of co-occurrence, co-citation, bibliographic coupling, and co-authorship. These visualizations reveal thematic clusters and collaboration networks, with spatial arrangement and color coding enhancing the interpretation of complex bibliometric structures.

Although various tools are available for bibliometric analysis and visualization, such as Bibliometrix (R package), Gephi, and CiteSpace, etc., VOSviewer was selected because of its robust capabilities in generating science mapping visualizations for large datasets. VOSviewer effectively supports co-authorship, co-occurrence, co-citation, and bibliographic coupling analyses, offering clear and well-structured clustering outputs suitable for exploratory field-level reviews. Although it does not calculate network centrality indicators, the tool’s visual clustering was deemed sufficient to uncover and interpret meaningful patterns in the sustainable fashion literature. The choice of software was guided by the study’s objective to deliver a comprehensive, interpretable, and reproducible overview of the intellectual landscape.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Overview

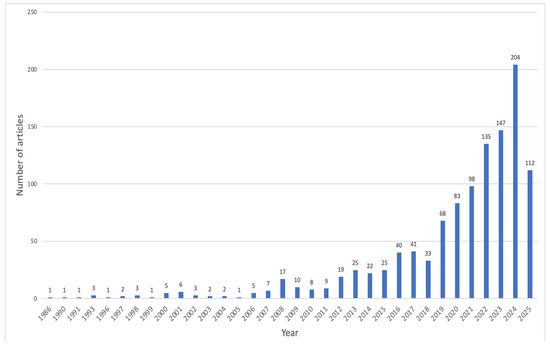

The temporal distribution of articles on sustainable fashion reveals an accelerating growth trend over the last four decades (Figure 1). From the late 1980s to the early 2000s, research output on sustainable fashion remained sporadic and marginal, with the annual number of publications rarely exceeding five. During this period, sustainable fashion was still a nascent concept that had not yet materialized into a clearly defined field of academic inquiry [24].

Figure 1.

Numbers of articles on sustainable fashion (1986–2025).

A moderate increase began around 2007–2015, with publication counts gradually rising yet remaining below 30 articles per year. This period reflects the initial institutionalization of sustainability concerns within the fashion domain, coinciding with growing global awareness of environmental issues [9]. Nevertheless, sustainable fashion research was still in its formative stage during these years.

A marked inflection point is observed from 2016 onwards. Between 2016 and 2019, the number of publications further rose and the steepest surge occurred from 2020 onward, with publication counts exceeding 80 per year. In 2024, the field reached its peak to date, with more than 200 articles published in a single year. The exceptional growth between 2020 and 2023 can be attributed to several factors. First, sustainability has become a central theme in fashion industry strategy, consumer activism, and regulatory policy, thereby drawing scholarly interest from diverse disciplines [2]. Second, the COVID-19 pandemic likely prompted a broader societal reflection on sustainability, resilience, and responsible consumption, further catalyzing research activity [45]. Finally, increased funding opportunities and journal Special Issues dedicated to sustainability may have contributed to this surge [46].

The dip observed in 2025 is due to incomplete data at the time of data collection, as not all articles for the year had been indexed in the database. This temporal lag is common in bibliometric studies conducted mid-year and should not be interpreted as a real decline in scholarly interest.

The disciplinary distribution of sustainable fashion research underscores the field’s interdisciplinary nature and highlights the diverse academic communities contributing to its development. Table 1 shows the subject areas with at least 100 articles, reflecting a broad range of intellectual traditions which encompass social sciences, engineering, environmental studies, and beyond.

Table 1.

Subject areas of articles on sustainable fashion.

The most dominant subject area is “Social Sciences,” accounting for 473 articles. This prominence reflects the critical role of sociocultural perspectives in sustainable fashion scholarship, especially regarding consumer behavior, ethical values, societal norms, and policymaking [31]. Social scientists often examine how sustainability is understood, practiced, and institutionalized within different cultural contexts, making them central to the discourse [13].

In second place is “Business, Management and Accounting” (417 articles), underscoring the growing academic focus on corporate sustainability strategies, green marketing, and the integration of ESG (Environmental, Social, Governance) practices in fashion enterprises [22]. This also indicates the business sector’s increasing acknowledgment of sustainability as a strategic priority [14].

“Environmental Science” ranks third with 268 articles, reflecting the ecological concerns of the field. This body of work typically addresses the environmental impacts of textile production, pollution, waste management, and life cycle assessments of clothing materials and processes [2]. The strong representation of this domain confirms the environmental imperative at the core of sustainable fashion [24].

“Arts and Humanities” follows with 216 articles, a testament to the relevance of design philosophies, aesthetics, historical narratives, and cultural critiques in shaping sustainable fashion [25]. This includes discussions on slow fashion, artistic expressions of resistance to consumerism, and the role of fashion as a medium of communication [47].

“Engineering” and “Energy,” with 195 and 172 articles, respectively, contribute technical insights into textile innovation, eco-efficient production technologies, and renewable energy use in manufacturing processes [48]. These two fields are essential in advancing sustainable materials, smart textiles, and energy-saving solutions in the fashion value chain [49].

The contributions of “Computer Science” (139 articles) and “Materials Science” (136 articles) reflect the adoption of digital technologies, such as AI and 3D printing, and the exploration of novel materials, such as biodegradable fibers, in the fashion production signifying the field’s movement toward technological integration and innovation [50].

Also noteworthy is “Economics, Econometrics and Finance” (117 articles). This subject area focuses on sustainability performance metrics, consumer demand modeling, pricing strategies for green products, and the economic impacts of circular business models [51].

4.2. Keywords

There are 3295 keywords in the studied articles on sustainable fashion, 21 of them appeared at least 30 times (Table 2). These keywords provide a snapshot of the breath and core concepts of the research field [52]. Unsurprisingly, the most dominant keyword is “Sustainability,” with 308 occurrences, followed closely by “sustainable fashion” (286 occurrences) and “sustainable development” (110 occurrences). These terms reflect the centrality of sustainability as both a guiding principle and a unifying objective in contemporary fashion discourse. The prominence of sustainable development further suggests alignment with global policy frameworks such as the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), reinforcing the idea that fashion is increasingly seen as a sector with significant environmental and social implications [2].

Table 2.

Keywords on sustainable fashion.

The keywords “fashion” (103 occurrences), “slow fashion” (80 occurrences), “fashion industry” (73 occurrences), and “fast fashion” (61 occurrences) point to a strong interest in the comparative dynamics of traditional and sustainable production-consumption models. The contrast between fast and slow fashion has been widely examined in terms of ecological impact, supply chain speed, and consumer awareness [14].

Other frequently occurring keywords such as “circular economy” (69 occurrences), “textile industry” (49 occurrences), and “clothing Industry” (48 occurrences) indicate a systemic approach to sustainability. These terms suggest a growing body of literature focused on industrial transitions, particularly the shift toward circular production models and more resource-efficient manufacturing practices [53].

Keywords such as “consumption behavior” (51 occurrences), “purchase intention” (42 occurrences), “consumer behavior” (36 occurrences), “perception” (35 occurrences), and “social media” (34 occurrences) highlight the role of individual agency and cultural factors in sustainable fashion. These terms are often linked to studies exploring psychological drivers, decision-making frameworks, and the influence of digital platforms on awareness and engagement [18,31].

The keywords “ethical fashion” (44 occurrences), “ethics” (31 occurrences), and “marketing” (35 occurrences) suggests strong attention to moral considerations and strategic communication. These terms are associated with the ways brands convey their sustainability values and the ethical judgments consumers make when engaging with fashion products [29].

Keywords like “environmental impact” (35 occurrences) and “human” (47 occurrences) emphasize the broader consequences of fashion practices, both ecological and social, indicating a human-centered approach to sustainability that integrates worker rights, social equity, and environmental stewardship [48].

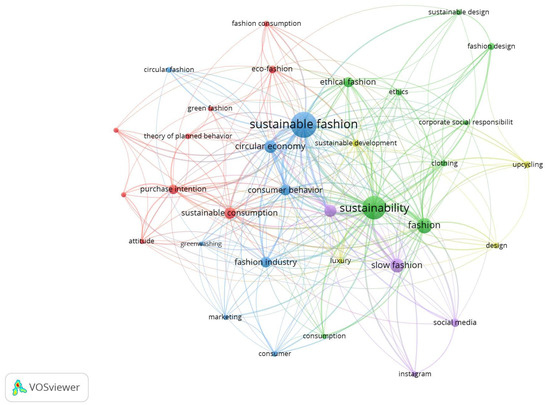

Co-occurrence analysis was conducted to explore the thematic associations between keywords. A total of 34 keywords that co-occurred in the literature at least ten times were grouped into five clusters (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Co-occurrence clusters of keywords on sustainable fashion (Note: Colors indicate the cluster membership assigned by VOSviewer to group related keywords).

The red cluster theme is “Consumer Behavior” as it comprises keywords such as “attitude, “purchase intention,” “perceived value,” “fashion consumption,” “sustainable consumption,” “second-hand clothing,” “eco-fashion,” “green fashion,” and “Theory of Planned Behavior.” These terms are conceptually aligned with individual-level decision-making and motivations to engage in sustainable fashion behaviors. Specifically, the “Theory of Planned Behavior” [32] has been frequently employed to examine the relationship between consumers’ attitudes and their intentions to purchase sustainable products. Other factors shaping purchase intentions in fashion contexts include perceived value, social norms, and environmental concern [31,54]. The presence of “second-hand clothing” and “fashion consumption” underscores interest in alternative forms of consumption that contribute to circularity, while the inclusion of “eco-fashion,” “green fashion,” and “ethical fashion” suggests overlapping terminologies associated with sustainability communication and labeling [10].

The green cluster “Design Ethics” includes keywords such as “sustainability,” “sustainable design,” “fashion design,” “ethics,” “corporate social responsibility,” “consumption,” “clothing,” and “ethical fashion.” These keywords may reflect a focus on production-side considerations and ethical imperatives in the fashion system. The convergence of “fashion design” and “ethical fashion,” with “ethics” and “corporate social responsibility” indicates how design decisions are increasingly framed within ethical and sustainability paradigms [25,29].

The blue cluster “Circular Economy” includes keywords like “circular economy,” “circular fashion,” “consumer,” “consumer behavior,” “fashion industry,” “greenwashing,” “marketing,” and “sustainable fashion.” These keywords collectively highlight the convergence between systemic transformations toward circularity and the challenges of effectively communicating sustainability in the marketplace. The keywords “circular economy” and “circular fashion” reflect a macro-level shift toward regenerative production and consumption models [2,53]. Keywords “greenwashing” and “marketing” suggest ongoing concerns with the authenticity of sustainability claims and their influence on “consumer behavior” [55]. The inclusion of “fashion industry” as a node within this cluster further reinforces the structural perspective of sustainability in commercial and institutional settings.

The yellow cluster “Innovation” has keywords such as “design,” “luxury,” “sustainable development,” and “upcycling,” indicating an innovation-driven approaches to sustainability, particularly in relation to aesthetic, artisanal, and high-value practices. The presence of “luxury” within this cluster reflects the increasing scholarly and industry attention to reconciling exclusivity and craftsmanship with environmental responsibility [14]. “Upcycling” links creative reuse with environmental goals, showcasing how design ingenuity can be mobilized to extend product life and reduce waste [56]. Different from the green cluster “design ethics,” this cluster aligns with the broader discourse on sustainable development framed within global development agendas.

The purple cluster “Digital Media” includes keywords such as “fast fashion,” “slow fashion,” “instagram,” and “social media.” This grouping underscores the juxtaposition of “fast fashion” and “slow fashion” and the tension between accelerated consumption cycles and the emerging countermovement advocating for environmentally responsible fashion choices [57]. The inclusion of “instagram” and “social media” points to the increasing influence of digital communication in spreading sustainability messages, shaping consumer awareness, and influencing identity-driven consumption [58].

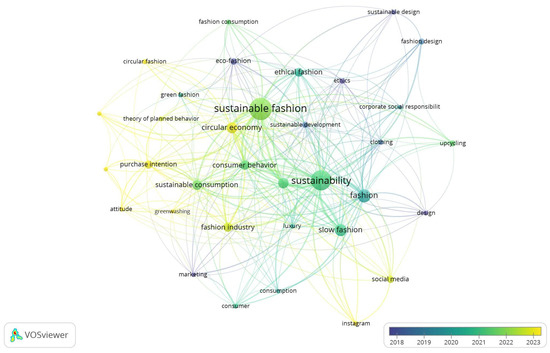

The temporal overlay visualization allows to trace the progression of thematic interests within the field over time. While keywords in purple and blue represent topics that emerged earlier, those in green and yellow are more recent (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Average time of occurrence of keywords on sustainable fashion.

The earlier topics were “fashion design,” “sustainable design,” “corporate social responsibility,” “ethics,” and “clothing.” These keywords indicate that early research primarily focused on production-side sustainability issues and ethical design practices [24].

As the field matured, interest began to expand toward system-level frameworks and consumption-related concerns. Keywords such as “sustainability,” “sustainable fashion,” “circular economy,” “fashion industry,” and “consumer behavior” suggest a broadening of the discourse to include institutional, economic, and behavioral aspects of sustainable fashion. In particular, circular economy and consumer behavior reflect growing scholarly efforts to bridge supply-side transformations with demand-side participation [2].

The most recent keywords include “social media,” “instagram,” “attitude,” “purchase intention,” “sustainable consumption,” and “theory of planned behavior”, pointing to a shift toward consumer psychology, social influence, and digital engagement in shaping sustainable fashion behaviors. The emphasis on social media and instagram also illustrates how the digital environment has become a powerful space for sustainability communication and advocacy [58].

4.3. Documents and Authors

Among the 1134 studied articles, 17 were cited more than 200 times (Table 3). These 23 articles reveal three research orientations, namely ethical and consumer behavior, sustainable business and supply chains, and conceptual development of sustainability-related models, echoing the thematic findings of the keyword analysis.

Table 3.

Highly cited documents on sustainable fashion.

Despite the diversity of topics covered in these articles, several of them can be grouped into related categories. First, McNeill and Moore [31], Joergens [10], Wiederhold and Martinez [59], and Lundblad and Davies [60] focused on ethical consumption and behavioral intention. These studies examine some central themes in understanding sustainable, including consumer attitudes, the attitude–behavior gap, and motivations for sustainable or second-hand fashion choices.

A second group focuses on definitional and theoretical work, such as Henninger et al. [9] on conceptualizing sustainable fashion and Clark [61] on the emergence of the slow fashion movement. The framework of marketing ethics by Hunt and Vitell [62], despite not fashion-specific, appears frequently cited for its relevance to ethical decision-making in marketing contexts.

A third group emphasizes business models, innovation, and supply chain practices, including de Brito et al. [63], Todeschini et al. [64], Choi and Luo [65], and Shen [66]. These papers contribute frameworks for evaluating sustainability performance, implementing blockchain and circular systems, and analyzing strategic practices of large firms, e.g., H&M.

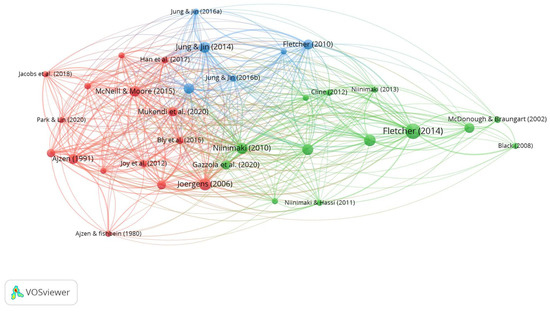

Co-citation analysis was conducted to explore the intellectual associations between articles on sustainable fashion. A total of 34 keywords co-cited in the literature at least 15 times were grouped into three clusters (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Co-citation clusters of documents on sustainable fashion (Note: Colors indicate the cluster membership assigned by VOSviewer to group related documents).

The red cluster includes empirical studies examining sustainable clothing choices, values, and motivations, e.g., Joergens [10], Joy et al. [14], McNeill and Moore [31], Han et al. [51], Bly et al. [67], and Harris et al. [68]. These works establish a psychological and attitudinal lens through which sustainable fashion consumption is understood. This cluster also highlights the contribution of the Theory of Planned Behavior [32] that provides the theoretical explanation of attitude–behavior relations.

The green cluster highlights the broader systems-oriented and sustainability perspectives. Key documents include Ellen MacArthur Foundation [4], Fletcher [24], McDonough and Braungart [69], and Black [70] alongside contributions by Niinimäki and her colleagues [2,11,71,72] on eco-clothing, design strategies, and fast fashion’s environmental toll. Additionally, included are studies on circular economy, retailing, and demographic perceptions of sustainability (e.g., Yang et al. [21], Gazzola et al. [73]). This cluster reflects a macro-level discourse concerned with systemic change, technological innovation, and structural barriers to sustainability.

The blue cluster represents definitional work and knowledge consolidation. It includes review articles and conceptual pieces aimed at framing the boundaries of the field, such as Henninger et al. [9], Fletcher [12,14], and Jung and Jin [74,75]. Sequence of publications also appears prominently, offering a theoretical examination of consumer motivations and sustainable business models. This cluster contributes to the field’s conceptual clarity, taxonomy, and interdisciplinary coherence.

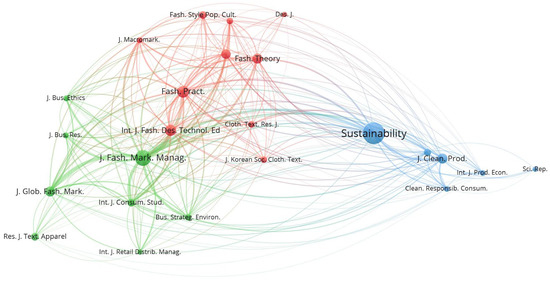

4.4. Journals

In total, 1134 articles on sustainable fashion were published in 557 journals. Table 4 lists the journals that published at least seven papers. The journal with the highest number of articles on sustainable fashion is Sustainability (Switzerland) (100 articles). This dominance can be attributed to the journal’s broad sustainability focus, inclusive editorial scope, and relatively rapid publication cycle, making it a preferred venue for interdisciplinary research on sustainable fashion.

Table 4.

Productive journals on sustainable fashion research.

The second most productive journal, Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management (50 papers), reflects the commercial and branding dimensions of sustainable fashion, particularly studies on ethical consumption, brand perception, and marketing strategy. Similarly, Fashion Practice (29 papers), Fashion Theory (20 papers), and International Journal of Fashion Design, Technology and Education (27 papers) underscore the influence of fashion-specific scholarship that emphasizes aesthetics, design innovation, and cultural critique.

Outlets with a sustainability or environmental orientation such as Journal of Cleaner Production (21 papers), Business Strategy and the Environment (9 papers), and Cleaner and Responsible Consumption (7 papers) indicate strong engagement with industrial ecology, sustainable production, and environmental impact assessment. These journals typically appear in higher Scopus percentiles, with many above the 90th percentile, suggesting both their quality and relevance to scholars aiming to reach broader environmental audiences.

It is also noteworthy that several consumer-focused and interdisciplinary journals such as International Journal of Consumer Studies (13 papers), Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services (10 papers), and Journal of Business Ethics (7 papers) host impactful research on consumption behavior, ethical decision-making, and corporate social responsibility.

To explore the intellectual associations between journals, bibliographic coupling analysis was conducted to group 24 journals coupled at least 15 times into three clusters (Figure 5). The red cluster encompasses a concentration of fashion-specific journals such as Fashion Practice, Fashion Theory, Fashion Style and Popular Culture, International Journal of Fashion Design, Technology and Education, and International Journal of Sustainable Fashion and Textiles. This cluster is characterized by a strong disciplinary alignment with fashion studies, textile design, and aesthetics. It also includes outlets like Clothing and Textiles Research Journal, Design Journal, and Journal of Macromarketing, which collectively suggest a close-knit scholarly network that emphasizes creative practice, cultural critique, and policy issues related to the fashion system. The inclusion of Sustainability Science Practice and Policy and Journal of the Korean Society of Clothing and Textiles also highlights regionally grounded and practice-oriented contributions within this thematic grouping.

Figure 5.

Bibliographic coupling clusters of journals on sustainable fashion (Note: Colors indicate the cluster membership assigned by VOSviewer to group related journals).

The green cluster is anchored in journals focused on consumer behavior, marketing, and business strategy. Key outlets include Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, International Journal of Consumer Studies, Journal of Business Research, Journal of Business Ethics, and Business Strategy and the Environment. This grouping indicates a strong emphasis on consumer decision-making, ethical consumption, retail innovation, and strategic management in the sustainable fashion domain. The presence of Research Journal of Textile and Apparel and Journal of Global Fashion Marketing further broadens this cluster to include global supply chain and branding perspectives.

The blue cluster comprises journals rooted in sustainability science, environmental engineering, and responsible consumption. These include high-impact journals such as Sustainability, Journal of Cleaner Production, Cleaner and Responsible Consumption, and International Journal of Production Economics. The thematic orientation here leans toward life cycle assessment, green production, environmental footprint analysis, and systems-level sustainability evaluations. The presence of Scientific Reports and Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services signals a cross-disciplinary openness and a tendency toward empirical, data-driven research that bridges environmental science and consumer studies.

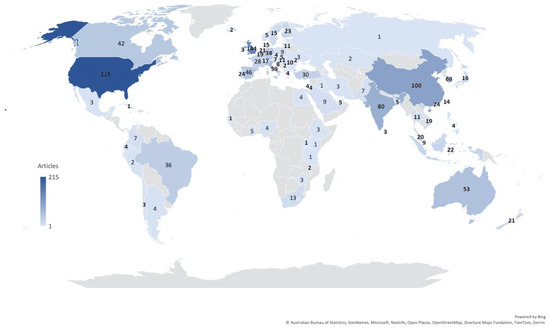

4.5. Countries

Figure 6 illustrates the geographic distribution of research articles on sustainable fashion, revealing a concentration of scholarly activity in economically advanced and industrialized nations. The United States leads the field with 215 articles, reflecting its strong academic infrastructure, significant market influence in fashion retail, and robust funding for sustainability-related research [76]. The dominance of U.S.-based publications may also be attributed to the country’s emphasis on consumer studies, environmental policy, and innovation in sustainable supply chains [77].

Figure 6.

Global distribution of articles on sustainable fashion.

The United Kingdom follows with 144 articles, suggesting its pivotal role in shaping both academic discourse and practical developments in sustainable fashion. UK universities and research centers have historically prioritized sustainability in creative industries, supported by public awareness and policy initiatives promoting responsible consumption [17].

China (100 articles) and India (80 articles) rank next, underscoring the growing research interest in sustainable fashion within the Global South, particularly in countries with significant manufacturing bases. China′s presence reflects increasing scholarly attention to green transformation in the textile industry, regulatory reforms, and technology-driven sustainability practices [78]. India’s contribution is similarly notable due to its rich textile heritage, rising consumer consciousness, and policy engagement with sustainability [79].

South Korea (69 articles) and Italy (59 articles) demonstrate the importance of government support in fostering sustainable fashion industry [80,81].

Countries such as Australia (53 articles), Spain (46 articles), Canada (42 articles), and Germany (38 articles) show consistent output, reflecting established academic ecosystems and active participation in global sustainability debates. Emerging contributors like Brazil, Turkey, Hong Kong, and several European nations (e.g., Portugal, Finland, Netherlands) also reflect a geographically diverse interest in sustainable fashion, suggesting a widening international research network.

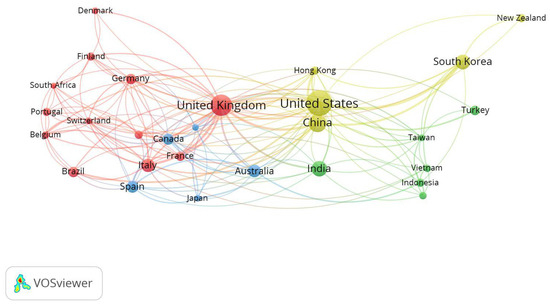

The co-authorship analysis of sustainable fashion research across 28 countries reveals a network of international collaborations organized into three distinct clusters (Figure 7). Each reflecting unique geographic, cultural, and academic synergies.

Figure 7.

International collaboration networks on sustainable fashion research (Note: Colors indicate the cluster membership assigned by VOSviewer to group related countries).

The red cluster comprises primarily Western European countries such as Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom, along with Brazil and South Africa. This grouping reflects a strong European-centered academic collaboration, underpinned by shared policy frameworks such as the European Union’s Green Deal, extensive sustainability mandates, and integrated funding programs like Horizon Europe [15]. The inclusion of Brazil and South Africa indicates their historical and cultural academic ties and knowledge exchange with European institutions, likely due to past colonial links and current EU-funded collaborative networks [82].

The green cluster includes countries such as India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Taiwan, Turkey, and Vietnam. These nations are characterized by their growing role in the global textile and apparel supply chains, which has motivated local research efforts on sustainable production and responsible sourcing [83]. The clustering suggests that these countries tend to collaborate within the regional context of Asia, driven by shared industrial challenges and regional development goals [84].

The blue cluster groups together Australia, Canada, Japan, Spain, and Sweden, nations known for their high research capacities and strong governmental support for sustainability agendas. These industrial countries share a common commitment to addressing sustainable fashion and consumption behaviors through cross-disciplinary scholarship [3].

Lastly, the yellow cluster brings together leading global research producers, including the United States, China, South Korea, New Zealand, and Hong Kong. These countries are positioned at the forefront of sustainable fashion research due to their large academic institutions, vibrant fashion markets, and technological innovation capacities [85]. Their co-authorship network reflects strong bilateral ties and high research volume, facilitating collaborations that transcend regional boundaries. Particularly, the U.S. and China anchor this cluster, indicating a strategic partnership in advancing technological and consumer-driven dimensions of sustainable fashion.

5. Conclusions

5.1. Summary of Findings

In this study, 1134 papers on sustainable fashion indexed in Scopus were examined using bibliometric methods to understand the development of this research field. The following conclusions can be drawn from the results:

- Annual Scientific Production: The trend in annual scientific output illustrates the rapid evolution of sustainable fashion from a niche concern into a vibrant and expanding field of scholarly inquiry, particularly over the past five years. This growth underscores the increasing urgency of sustainability challenges in the fashion industry and reflects a rising academic commitment to addressing these issues through interdisciplinary research.

- Interdisciplinary Subject Areas: The subject areas covered by sustainable fashion articles reveal the field’s inherently interdisciplinary nature. Research spans both qualitative and quantitative traditions, theoretical and applied approaches, and humanistic and scientific perspectives. This diversity highlights the complexity of sustainability challenges in fashion and suggests that effective solutions require collaboration across academic boundaries.

- Keyword Co-occurrence and Thematic Diversity: The frequency and co-occurrence of keywords reflect the multidimensional scope of sustainable fashion scholarship. It encompasses macro-level transformations and micro-level consumer choices, as well as ethical theory and technological innovation. The co-occurrence analysis identifies five major research themes: “Consumer Behavior,” “Design Ethics,” “Circular Economy,” “Innovation,” and “Digital Media.” These themes point to the coexistence of individual, organizational, systemic, and cultural concerns, and the complex interconnections among them. A temporal analysis further shows the evolution of sustainable fashion research, from early emphasis on design and corporate responsibility, to systemic change, and more recently, to individual behavior and digital engagement in response to broader social, technological, and economic transformations.

- Seminal Foundations and Knowledge Bases: Influential articles in the field reflect its multidisciplinary roots, encompassing normative and conceptual discussions as well as empirical investigations of consumer behavior and strategic operations. The prominence of both consumer-focused and practice-oriented studies indicates a dual emphasis on individual agency and organizational responsibility. Co-citation analysis identifies three core knowledge bases: micro-level behavioral research, system-level and policy-driven transformations, and overarching theoretical and conceptual frameworks.

- Dissemination Across Publication Venues: Sustainable fashion research is published across a wide range of outlets, including both domain-specific journals and broader multidisciplinary platforms. While some journals focus on fashion design and cultural inquiry, others are rooted in business, ethics, or environmental science. Each contributes unique perspectives and collectively forms a network of interconnected knowledge communities. This pattern of dissemination reinforces the field’s multidisciplinary character and growing scholarly legitimacy.

- Geographic Distribution and Collaboration Patterns: The geographic distribution of publications reflects the influence of factors such as market size, academic infrastructure, manufacturing capacity, and national sustainability agendas. The participation of Global North and Global South indicates an increasingly diverse global research landscape. Co-authorship analysis further reveals distinct patterns of collaboration shaped by regional, industrial, and academic contexts. These include Europe-centered knowledge networks, production-focused partnerships in the Asia-Pacific region, and global leadership in innovation and high-output research among major economies.

5.2. Theoretical and Practical Implications

This study contributes to the theoretical understanding of sustainable fashion by mapping the intellectual structure, thematic evolution, and collaborative networks in the research field of sustainable fashion. By identifying five keyword clusters, the study reveals that sustainable fashion is not a monolithic construct but a convergence of discourses from consumer psychology, ethical consumption, circular economy, digital media, and fashion design. These insights advance the theoretical foundation by offering a more integrative lens through which scholars can examine sustainability across production, consumption, and communication dimensions. The co-citation and bibliographic coupling analyses further delineate foundational works and emerging paradigms. The findings demonstrate that sustainable fashion draws upon theories from marketing ethics [62], behavioral science [32], and systems thinking [69].

Practically, the findings inform policymakers, educators, and industry practitioners about the knowledge hubs and scholarly trends that have shaped the field. For instance, the increasing attention to keywords like “social media” and “Instagram” underscores the importance of digital platforms in influencing consumer behavior. This suggests that sustainability campaigns may benefit from strategic social media engagement. Likewise, the prominence of “circular economy” and “greenwashing” as contemporary themes indicates a growing need for regulatory frameworks and corporate transparency. The identification of productive journals and countries also provides researchers with targeted venues and potential collaborators, enhancing research visibility and global cooperation.

5.3. Limitations and Recommendations

This study has a few limitations that should be aware of in the future research. First, this study relied solely on the Scopus database and included only English-language journal articles. While Scopus offers comprehensive and high-quality bibliographic data, it excludes non-English publications and other reputable sources such as Web of Science and Google Scholar. This may have led to the omission of valuable regional or non-English contributions to sustainable fashion research. Therefore, future research would be to expand the dataset by incorporating multiple databases such as Web of Science or Google Scholar and to include literature published in other major languages. This would offer a more inclusive and globally representative overview of the field.

Second, the current analysis focused only on peer-reviewed journal articles and excluded other relevant forms of academic and grey literature such as books, conference proceedings, and industry reports. These excluded sources may contain important conceptual developments, practical insights, and emerging trends, especially in a multidisciplinary field like sustainable fashion. To address this limitation, future studies could consider integrating books, theses, and grey literature to enrich the analysis and better capture diverse scholarly and practical contributions.

Third, the bibliometric analysis was based on metadata fields including titles, abstracts, and author keywords, which limits the depth of interpretation. Keyword co-occurrence analysis, while useful for revealing topical relationships, may oversimplify nuanced conceptual developments. Therefore, future research should consider complementing bibliometric analysis with full-text content analysis, topic modeling, or qualitative synthesis. Such approaches would enable a more comprehensive understanding.

Last but not least, this study employed VOSviewer as the primary tool for bibliometric visualization. While its clustering and mapping features are well-suited to the exploratory aims of this study, it does not produce centrality measures or enable advanced graph-theoretical modeling. Future research may consider using complementary tools such as Bibliometrix or CiteSpace to incorporate additional network metrics or test specific hypotheses within focused subdomains of sustainable fashion.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.-L.N.; methodology, S.-L.N.; software, S.-L.N. and S.-H.C.; validation, S.-L.N. and S.-H.C.; formal analysis, S.-L.N.; investigation, S.-L.N.; resources, S.-L.N.; data curation, S.-L.N.; writing—original draft preparation, S.-L.N.; writing—review and editing, S.-L.N. and S.-H.C.; visualization, S.-L.N.; supervision, S.-L.N.; project administration, S.-L.N.; funding acquisition, S.-L.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this paper were obtained from Scopus. Access to the original dataset is subject to the terms and conditions set by Scopus, and interested researchers may acquire the data directly from Scopus (https://www.scopus.com/).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- McKinsey & Company. The State of Fashion 2025. 2024. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/retail/our-insights/state-of-fashion (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Niinimäki, K.; Peters, G.; Dahlbo, H.; Perry, P.; Rissanen, T.; Gwilt, A. The environmental price of fast fashion. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2020, 1, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Environment Programme. Sustainability and Circularity in the Textile Value Chain: A Global Roadmap. 2023. Available online: https://www.unep.org/resources/publication/sustainability-and-circularity-textile-value-chain-global-roadmap (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Circular Business Models: Redefining Growth in the Fashion Industry. 2021. Available online: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/news/circular-business-models-in-the-fashion-industry (accessed on 24 August 2025).

- Bick, R.; Halse, A.; Ekenga, C.C. The global environmental injustice of fast fashion. Environ. Health 2018, 17, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cachon, G.P.; Swinney, R. The value of fast fashion: Quick response, enhanced design, and strategic consumer behavior. Manag. Sci. 2011, 57, 778–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claudio, L. Waste couture: Environmental impact of the clothing industry. Environ. Health Perspect. 2007, 115, A449–A454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Remy, N.; Speelman, E.; Swartz, S. Style That’s Sustainable: A New Fast-Fashion Formula. 2016. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/sustainability/our-insights/style-thats-sustainable-a-new-fast-fashion-formula (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Henninger, C.E.; Alevizou, P.J.; Oates, C.J. What is sustainable fashion? J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2016, 20, 400–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joergens, C. Ethical fashion: Myth or future trend? J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2006, 10, 360–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niinimäki, K.; Hassi, L. Emerging design strategies in sustainable production and consumption of textiles and clothing. J. Clean. Prod. 2011, 19, 1876–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, K. Slow fashion: An invitation for systems change. Fash. Pract. 2010, 2, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beard, N.D. The branding of ethical fashion and the consumer: A luxury niche or mass-market reality? Fash. Theory 2008, 12, 447–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joy, A.; Sherry, J.F., Jr.; Venkatesh, A.; Wang, J.; Chan, R. Fast fashion, sustainability, and the ethical appeal of luxury brands. Fash. Theory 2012, 16, 273–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Circular Economy Action Plan: For a Cleaner and More Competitive Europe. 2020. Available online: https://www.eu2020.de/resource/blob/2429166/156d2d98b66b2ff28b6990161eed91e9/12-17-kreislaufwirtschaftsaktionsplan-bericht-de-data.pdf (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Brydges, T. Closing the loop on take, make, waste: Investigating circular economy practices in the Swedish fashion industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 293, 126245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henninger, C.E.; Alevizou, P.J.; Goworek, H.; Ryding, D. Sustainability in Fashion: A Cradle to Upcycle Approach; Henninger, C.E., Alevizou, P.J., Goworek, H., Ryding, D., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busalim, A.; Fox, G.; Lynn, T. Consumer behavior in sustainable fashion: A systematic literature review and future research agenda. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2022, 46, 1804–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zakaria, N. Designers’ potential in sustainable fashion: A systematic literature review. Ind. Text. 2023, 74, 718–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, S.; Nayak, L. Marketing sustainable fashion: Trends and future directions. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Song, Y.; Tong, S. Sustainable retailing in the fashion industry: A systematic literature review. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köksal, D.; Strähle, J.; Müller, M.; Freise, M. Social sustainable supply chain management in the textile and apparel industry—A literature review. Sustainability 2017, 9, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daukantiene, V. Analysis of the sustainability aspects of fashion: A literature review. Text. Res. J. 2023, 93, 991–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, K. Sustainable Fashion and Textiles: Design Journeys; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 1–288. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher, K.; Tham, M. Earth Logic Fashion Action Research Plan; Fletcher, K., Tham, M., Eds.; The J J Charitable Trust: London, UK, 2019; Available online: https://katefletcher.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Earth-Logic-plan-FINAL.pdf (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Gwilt, A. A Practical Guide to Sustainable Fashion; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 2014; pp. 1–168. [Google Scholar]

- McKinsey & Company. Biodiversity: The Next Frontier in Sustainable Fashion. 2020. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/retail/our-insights/biodiversity-the-next-frontier-in-sustainable-fashion (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- United Nations Economic Commission for Europe. Fashion and the SDGs: What Role for the UN? 2018. Available online: https://unece.org/fileadmin/DAM/RCM_Website/RFSD_2018_Side_event_sustainable_fashion.pdf (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Shen, B.; Wang, Y.; Lo, C.K.Y.; Shum, M. The impact of ethical fashion on consumer purchase behavior. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2012, 16, 234–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.; Jin, B. A theoretical investigation of slow fashion: Sustainable future of the apparel industry. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2014, 38, 510–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeill, L.; Moore, R. Sustainable fashion consumption and the fast fashion conundrum: Fashionable consumers and attitudes to sustainability in clothing choice. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2015, 39, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabas, C.S.; Whang, C. A systematic review of drivers of sustainable fashion consumption: 25 years of research evolution. J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 2022, 13, 151–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnstone, M.L.; Tan, L.P. Exploring the gap between consumers’ green rhetoric and purchasing behavior. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 132, 311–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peleg Mizrachi, M.; Tal, A. Regulation for promoting sustainable, fair and circular fashion. Sustainability 2022, 14, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turker, D.; Altuntas, C. Sustainable supply chain management in the fast fashion industry: An analysis of corporate reports. Eur. Manag. J. 2014, 32, 837–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranfield, D.; Denyer, D.; Smart, P. Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management knowledge by means of systematic review. Br. J. Manag. 2003, 14, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, H. Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 104, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donthu, N.; Kumar, S.; Mukherjee, D.; Pandey, N.; Lim, W.M. How to conduct a bibliometric analysis: An overview and guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 133, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, S.-L.; Wong, F.-M. Recent developments in research on food waste and the circular economy. Biomass 2024, 4, 472–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özdil, M.A.; Konuralp, E. Dressing the future: The bibliometric interplay between sustainability and fashion studies amidst the neoliberal era. Fash. Pract. 2024, 17, 156–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruslan, B.; Maulina, E.; Tahir, R.; Rivani; Muftiadi, R.A. Sustainable consumer behavior: Bibliometric analysis for future research direction in Muslim fashion context. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prado, N.M.; Silva, M.H.P.; Kaneko, C.S.K.; Silva, D.V.; Giusti, G.; Saavedra, Y.M.B.; Silva, D.A.L. Sustainability in fashion retail: Literature review and bibliometric analysis. Gest. Prod. 2022, 29, e13322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, Y.; Srivastava, A. COVID-19 pandemic and sustainability: A bibliometric and literature review. Benchmarking Int. J. 2022, 29, 1991–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Duić, N. Advanced methods and technologies towards environmental sustainability. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2021, 23, 709–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorpe, A. The Designer’s Atlas of Sustainability: Charting the Concept; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2007; pp. 1–223. [Google Scholar]

- Parisi, M.L.; Fatarella, E.; Spinelli, D.; Pogni, R.; Basosi, R. Environmental impact assessment of an eco-efficient production for coloured textiles. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 108, 514–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caniato, F.; Caridi, M.; Crippa, L.; Moretto, A. Environmental sustainability in fashion supply chains: An exploratory case-based research. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2012, 135, 659–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glogar, M.; Petrak, S.; Mahnić Naglić, M. Digital technologies in the sustainable design and development of textiles and clothing—A literature review. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Seo, Y.; Ko, E. Staging luxury experiences for understanding sustainable fashion consumption: A balance theory application. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 74, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aria, M.; Cuccurullo, C. Bibliometrix: An R-tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis. J. Informetr. 2017, 11, 959–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchherr, J.; Reike, D.; Hekkert, M. Conceptualizing the circular economy: An analysis of 114 definitions. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 127, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Seock, Y.K. The roles of values and social norm on personal norms and pro-environmentally friendly apparel product purchasing behavior: The mediating role of personal norms. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 51, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamkiewicz, J.; Kochańska, E.; Adamkiewicz, I.; Łukasik, R.M. Greenwashing and sustainable fashion industry. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2022, 38, 100710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aus, R.; Moora, H.; Vihma, M.; Unt, R.; Kiisa, M.; Kapur, S. Designing for circular fashion: Integrating upcycling into conventional garment manufacturing processes. Fash. Text. 2021, 8, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, M.K. Slow fashion in a fast fashion world: Promoting sustainability and responsibility. Laws 2019, 8, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dantas, B.L.L.; Abreu, N.R. An analysis of the influence of the conspicuous consumption of fast fashion on identity construction on Instagram. Rev. Adm. Mackenzie 2020, 21, eRAMG200043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiederhold, M.; Martinez, L.F. Ethical consumer behaviour in Germany: The attitude–Behaviour gap in the green apparel industry. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2018, 42, 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundblad, L.; Davies, I.A. The values and motivations behind sustainable fashion consumption. J. Consum. Behav. 2016, 15, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, H. SLOW + FASHION—An oxymoron—Or a promise for the future …? Fash. Theory 2008, 12, 427–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, S.D.; Vitell, S. A general theory of marketing ethics. J. Macromark. 1986, 6, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Brito, M.P.; Carbone, V.; Blanquart, C.M. Towards a sustainable fashion retail supply chain in Europe: Organisation and performance. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2008, 114, 534–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todeschini, B.V.; Cortimiglia, M.N.; Callegaro-de-Menezes, D.; Ghezzi, A. Innovative and sustainable business models in the fashion industry: Entrepreneurial drivers, opportunities, and challenges. Bus. Horiz. 2017, 60, 759–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, T.-M.; Luo, S. Data quality challenges for sustainable fashion supply chain operations in emerging markets: Roles of blockchain, government sponsors and environment taxes. Transp. Res. E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2019, 131, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, B. Sustainable fashion supply chain: Lessons from H&M. Sustainability 2014, 6, 6236–6249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bly, S.; Gwozdz, W.; Reisch, L.A. Exit from the high street: An exploratory study of sustainable fashion consumption pioneers. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2015, 39, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, F.; Roby, H.; Dibb, S. Sustainable clothing: Challenges, barriers and interventions for encouraging more sustainable consumer behaviour. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2016, 40, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonough, W.; Braungart, M. Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 1–208. [Google Scholar]

- Black, S. Eco-Chic: The Fashion Paradox; Black Dog Publishing: London, UK, 2008; pp. 1–192. [Google Scholar]

- Niinimäki, K. Eco-clothing, consumer identity and ideology. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 18, 150–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niinimäki, K. Sustainable Fashion: New Approaches; Aalto University: Helsinki, Finland, 2013; pp. 1–176. [Google Scholar]

- Gazzola, P.; Pavione, E.; Pezzetti, R.; Grechi, D. Trends in the fashion industry—The perception of sustainability and circular economy: A gender/generation quantitative approach. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.; Jin, B. From quantity to quality: Understanding slow fashion consumer for sustainability and consumer education. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2016, 40, 410–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.; Jin, B. Sustainable development of slow fashion businesses: Customer value approach. Sustainability 2016, 8, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Hawkins, C.; Berman, E. Financing sustainability and stakeholder engagement: Evidence from U.S. cities. Urban Aff. Rev. 2014, 50, 806–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, K. Environmental preferences and consumer behavior. Econ. Lett. 2016, 148, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Cui, X.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, X.; Li, W. Carbon neutrality and green technology innovation efficiency in Chinese textile industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 395, 136453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellappa, K. Sustainable transition to circular textile practices in Indian textile industries: A review. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2025. advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, Y.; Na, D.K. Investigating the sustainability of the Korean textile and fashion industry. Int. J. Cloth. Sci. Technol. 2015, 27, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoppelletto, A.; Santini, E.; Rossignoli, C.; Ricciardi, F. Interfirm collaboration enhancing twin transition: Evidence from the Italian fashion industry. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2025, 72, 546–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoekman, J.; Frenken, K.; Tijssen, R.J. Research collaboration at a distance: Changing spatial patterns of scientific collaboration within Europe. Res. Policy 2010, 39, 662–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunyemi, A.A.; Diyaolu, I.J.; Awoyelu, I.O.; Bakare, K.O.; Oluwatope, A.O. Digital transformation of the textile and fashion design industry in the Global South: A scoping review. In Towards New e-Infrastructure and e-Services for Developing Countries; Saeed, R.A., Bakari, A.D., Sheikh, Y.H., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; Volume 499, pp. 372–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadhna; Greeshma, S.; Kumar, R.; Mokanaasri, E. Introduction to the Asian textile and garment industry. In Consumption and Production in the Textile and Garment Industry: SDGs and Textiles; Sadhna, Kumar, R., Memon, H., Greeshma, S., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2024; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silobrit, I.; Jureviciene, D. Assessing circular textile industry development. Econ. Cult. 2023, 20, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).