1. Introduction

Rural areas in Europe are home to 137 million people, accounting for 30% of the continent’s population and covering 80% of its territory [

1]. These areas are well acknowledged and esteemed for their agricultural production, natural resource management, conservation of landscapes, and recreational and tourism activities. However, rural areas are facing various changes, such as migration, demographic change, the dismantling of infrastructure [

2], climate change and environmental degradation, agricultural restructuring, decrease in farms, and an aging farming population [

3] with relatively serious consequences affecting the quality of life of the rural population. Nonetheless, in certain areas, these challenges are being tackled through innovative solutions [

2]. Social innovation processes can be considered among these, leading to solutions that, through the voluntary involvement of the local community, revitalize the rural fabric [

4] and ameliorate their socio-economic situation [

5]. It is important to emphasize that there is a growing body of research that recognizes the importance of the concept of social innovation in rural areas and highlights its crucial role in sustainable rural development processes [

6]. Several European research projects have also focused on these issues. Some examples are the European projects “Social Innovation in Marginalized Rural Areas (SIMRA)” and “Enhancing Social Innovation in Rural Areas” (ESIRA).

There are different interpretations of the concept of social innovation [

6,

7,

8], and although there is no universally accepted definition, there is broad consensus that social innovation encompasses both the process of transforming social practices (such as attitudes, behaviors, and collaborative networks) and the resulting outcomes, including new products and services (such as innovative ideas, models, services, and new organizational forms) [

9]. The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) also recognizes the role of social innovation in rural areas. With its report, “Assessing the Framework Conditions for Social Innovation in Rural Areas [

10],” the OECD aims to provide policymakers with guidance on these issues. The OECD document defines social innovation as “seeking new answers to social and societal problems and referring to new solutions that aim primarily to improve the quality of life of individuals and communities by increasing their well-being as well as their social and economic inclusion [

10].” This definition shows how the concept of social innovation can be present in various rural sectors, including agriculture, tourism, and medical care. In this vein, government bodies such as the European Union are certainly moving forward with their vision, as an example with the strategy “The long-term vision for the EU’s rural areas [

11]”, focusing the attention on rural areas and seeking to promote actions that will make them stronger, more connected, more resilient, and more prosperous. In this context, social innovation practices can significantly impact both the present and the future of rural areas.

Starting with these important aspects, the research questions that guided this work are the following:

RQ1: What are the main research topics involving the concepts of social innovation and rural areas?

RQ2: Which are the authors more active in these topics?

RQ3: Which countries are more involved in these research topics?

As Ahlmeyer and Volgmann [

3] note, European rural areas can vary significantly from one another, and their heterogeneity can lead them to face different challenges. However, in general, they also possess some shared characteristics. In addition to the significant environmental, social, and economic challenges listed above, such as demographic change, climate change, and agricultural restructuring, rural areas also have considerable potential for regeneration, such as the development of local food chains, the transition to sustainable agriculture, and the diversification of the rural economy. In detail, agriculture is fundamentally connected to rural communities, acting as a foundation for their economic vibrancy, social structure, and environmental sustainability. It offers vital employment and revenue, bolsters ancillary businesses, affects the delivery of public services, and enhances the overall development and resilience of rural communities globally [

12,

13].

For these reasons, several European policies targeting rural areas, such as the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), aim to enhance the vitality and economic sustainability of rural areas through dedicated measures. Key objectives include fostering the competitiveness of agriculture and forestry, promoting the sustainable management of natural resources and climate action, and ensuring balanced territorial development by supporting rural economies and communities [

14]. The CAP support for rural development indeed foresees the need for fundamental social changes and places great importance on social innovation as an essential part of this process [

15].

In this regard, considering the endogenous resources characteristic of many rural areas, such as agriculture and agro-forestry resources, also understood from a multifunctional perspective [

16,

17,

18,

19], we ask the following research question:

RQ4: Is agriculture part of social innovation initiatives in rural areas?

By answering the above research questions, this paper aims to provide researchers with a comprehensive and objective view of the concept of social innovation in rural areas. Compared to similar studies that use bibliometric analysis for similar topics [

20,

21], this article highlights the most recurring themes of social innovation in rural areas from a contemporary perspective. Encompassing various themes such as sustainability and innovation, and the organizational models that can characterize social innovation in rural areas, this review will cover a wide range of topics. The final aim is to highlight the vital role of social innovations in rural areas and provide guidance for future research and policies. Through productivity measurement and a bibliometric analysis, this article addresses the themes around which this research revolves, analyzing their positioning and evolution over time.

The outline of the paper is as follows:

Section 2 presents the methodology;

Section 3 presents the main results obtained.

Section 4 explores the results through discussion.

Section 5 presents the conclusions and suggestions for future work.

2. Materials and Methods

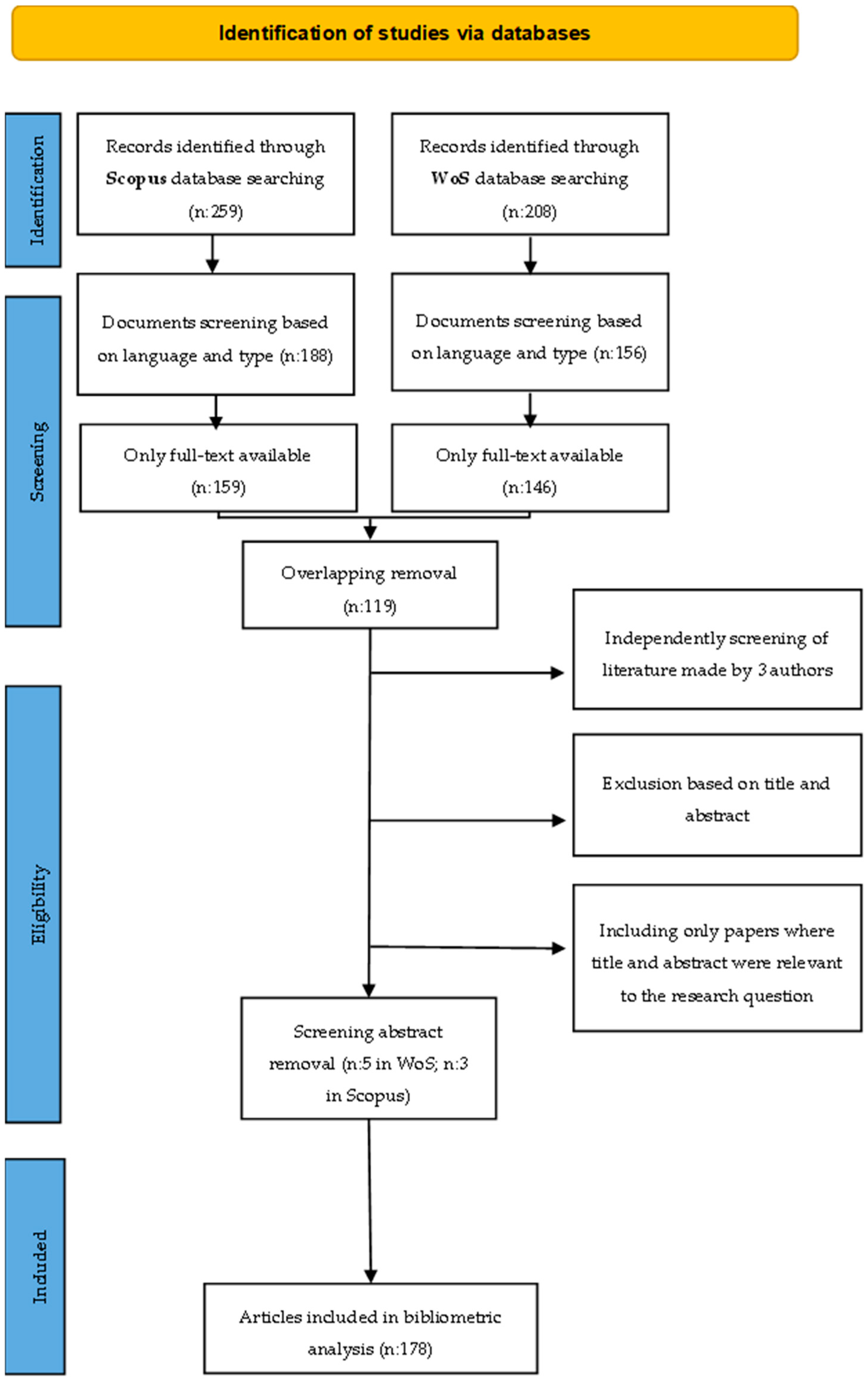

This research was carried out considering two different databases, Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus. The two platforms were selected because they are widely acknowledged for their extensive coverage of prestigious, peer-reviewed journals and articles of exceptional quality [

22]. By adopting these two reliable databases, we have expanded the range of suitable documents [

23]. To conduct this study, a sequence of keywords able to answer the research questions was developed. In this case, considering the present interest in the research topic and its wide range of action, the research string was kept as general as possible, with the aim of including all the published works. The research string, using Boolean operators, was the following: “social innov*” AND “rural area*.” Following Van der Have & Rublanca [

20] and Fernandes da Silva et al. [

21], the character (*) was used to recuperate the variations in social innovation, or innovations and social innovator, and rural area or areas. In Scopus, the search was applied for “Article Title, Abstract, Keywords,” while in WoS it was applied for “Topic,” because, in this way, the database would be capable of searching for the title, abstract, keyword plus, and author keywords. The data collection was performed on 27 May 2025. This first step highlighted a total of 467 documents, 208 in WoS and 259 in Scopus. Consequently, a series of filters were applied. Papers were limited according to the type of publication, such as article, review, and book chapter, only published in English, and under the final stage of publication, bringing our sample down to 344 documents (156 for WoS and 188 for Scopus). Subsequently, to continue the selection process, only documents where the full text was available to read were selected, resulting in 305 documents obtained (146 for WoS and 159 for Scopus). To avoid cases of overlapping articles between the two databases, a review was also carried out in this regard, noting 119 overlaps. Finally, only documents where the title and abstract were relevant to the research question were selected, resulting in a total of 178 documents obtained (141 from WoS and 37 from Scopus). This last action was a screening procedure performed independently by three authors [

23], and from this moment (3 June 2025) the two databases were merged as one [

22]. The database includes papers that range from 2013 to 2025, principally in top-tier scientific journals dedicated to rural studies (i.e., the

Journal of Rural Studies,

Sociologia Ruralis, and

European Countryside).

For the aim of this study, a productivity measurement was applied to analyze the number of documents published each year, the most productive countries, the principal publishing sources, and the main research areas. Productivity measures are useful for evaluating the status of specific topics in the literature, as well as its research trends and evolution over time [

22]. Moreover, through the software VOSviewer (version 1.620, developed by Nees Jan van Eck and Ludo Waltman at Leiden University’s Centre for Science and Technology Studies (CWTS)), the database was used to conduct bibliometric analysis [

24], highlighting the networks created with co-authorship analyses of countries and authors, co-occurrence analyses relating to keywords, and concluding with a citation analysis of sources, authors, documents, and countries. This type of analysis was chosen because it is relevant to our research question, and, using computational algorithms and visualization tools, it can reveal relevant information from the literature, providing a more structured review [

23].

Figure 1 shows a complete overview of the document selection process.

3. Results

In the following section, the main results obtained from the productivity measurement and the bibliometric analysis are presented.

3.1. Productivity Measurement: Years, Countries, Journals, and Research Areas

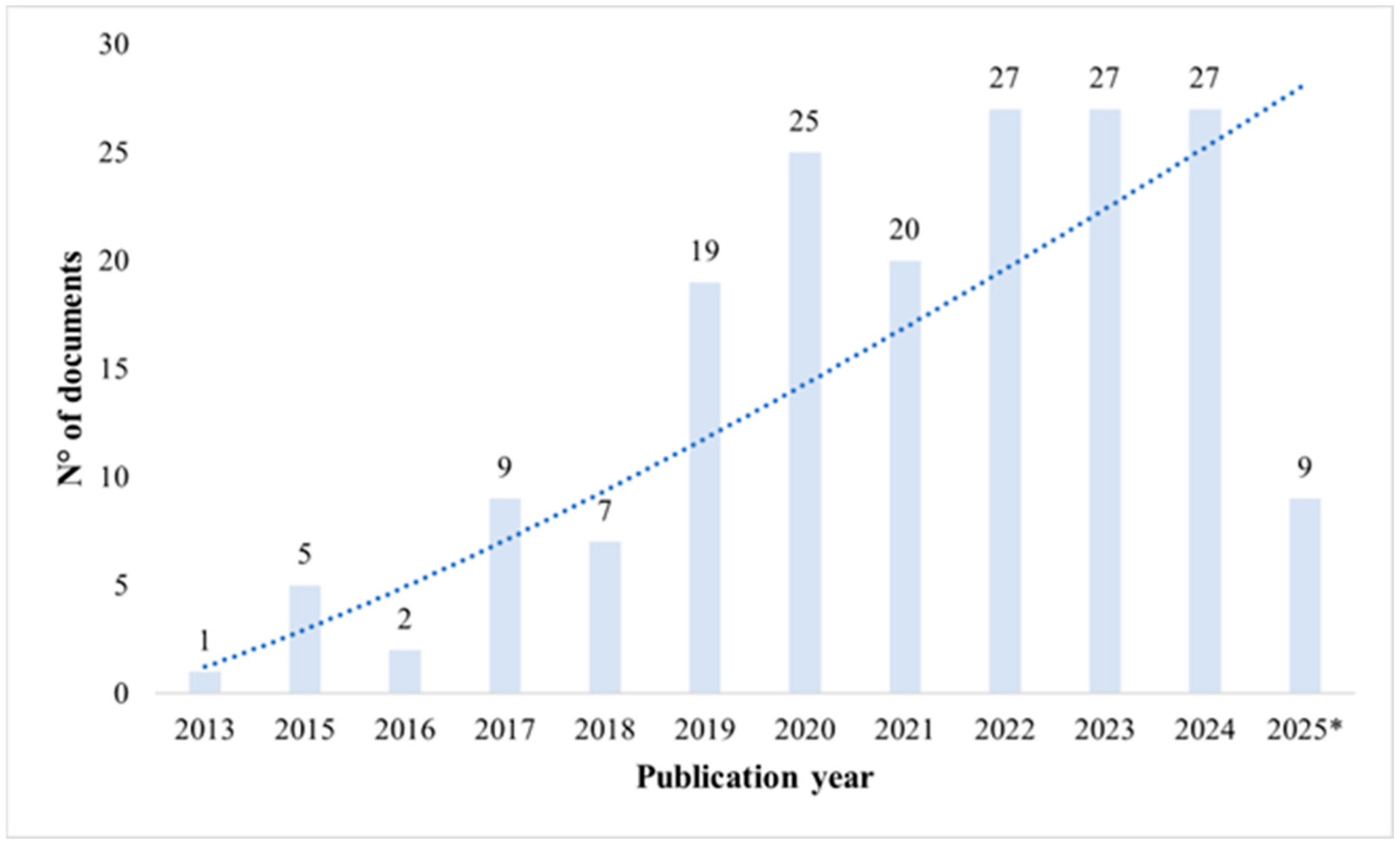

Figure 2 shows the number of papers published on social innovation implemented within the rural areas in each year. It is noticed that a growing trend is highlighted, revealing a steady increase in interest among scholars in these topics of social innovation and rural areas. From 2017 onwards, these topics began to attract significant attention from the scientific community, a trend which continues to this day, with a level of interest that seems to have stabilized at significant levels in recent years. The intersection between these topics is gaining more credibility year after year.

Figure 3 illustrates the top ten countries with the highest number of publications; specifically, Italy is the most productive country (47 publications), followed by Germany (26) and Spain (23). In addition, the figure clearly shows that Europe is currently responsible for most of the scientific production in this field. This also confirms the growing institutional and political interest in these topics that have been developing in recent years [

11].

Figure 4 presents the top ten journals with the highest number of published documents in the field of social innovation and rural areas. Altogether, these sources published 99 articles, representing 56% of the 178 papers in the database. The journal with the most publications is

Sustainability with 34 publications, followed by the

Journal of Rural Studies with 19 and

Forest Policy and Economics. Afterwards, we found

European Countryside to have nine documents and

Sociologia Ruralis to have eight documents. The distribution of the articles indicates that the research has been published in a wide range of high-level journals, reflecting the interdisciplinary nature of the topics and their widespread interest.

Lastly, according to the Scopus and WoS classifications, the most important research areas in relation to social innovation and rural areas are environmental science (69 documents), social sciences (44 documents), business and economics (32 documents), agriculture (11 documents), and forestry (10 documents). The heterogeneity of the main research areas highlights the transdisciplinary nature of these subjects, emphasizing the need for comprehensive approaches to analysis.

3.2. Bibliometric Analysis: Co-Authorship by Countries

Figure 5 presents the network visualization map for the co-authorship, regarding the number of documents of a country. In this representation, the size of the circle indicates the number of documents produced, and the proximity of the labels reflects the correlation between the number of co-authored documents. Only countries that published at least three documents were considered. A total of 27 countries were identified. The figure only presents the elements connected within the network.

In this case, the criterion of co-authorship indicates the collaboration between countries in the development of articles. Italy is the country with the highest number of articles published (47), followed by Germany (26) and Spain (23). Italy is also characterized by strong cooperative dynamics, with links to 18 other countries in the network; similar dynamics also characterize Germany and Spain. From this perspective, the countries that seem to remain the most isolated are those outside the European zone, such as Brazil, China, and Colombia. Perhaps future research will also lead to new partnerships in this direction.

One of the key features of VOSviewer is the ability to apply overlay visualizations to the network. In this overlay, darker colors represent older items, while brighter colors indicate newer ones. The score of the item is represented by the average publication year of the documents. Darker colors (blue) represent items published earlier. Brighter colors (greenish and yellow) mean that the country started publishing later.

Figure 6 displays an overlay visualization of co-authorship among countries.

The countries that initially began publishing on the topic of social innovation and rural areas are primarily members of the European Union, specifically Greece, the Netherlands, and Austria. The most productive countries in this field, including Italy, Germany, and Spain, have more recent publications. Additionally, Colombia and Brazil have more recently written about these issues on average. This pattern may help explain the results shown in

Figure 5, which indicate their relatively low scientific output and limited networking capacity.

3.3. Bibliometric Analysis: Co-Authorship by Authors

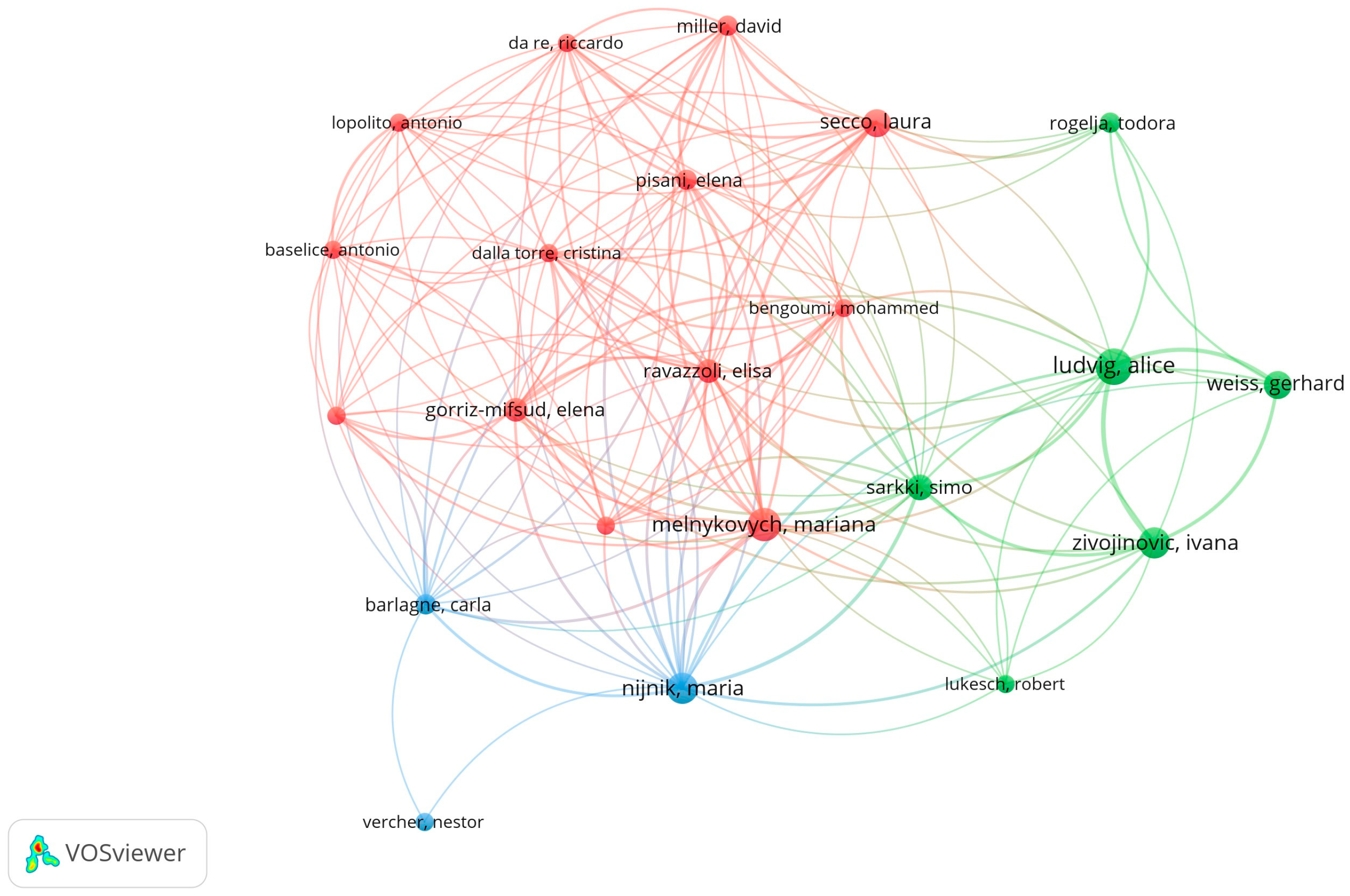

Figure 7 presents a network visualization map of the authors’ co-authorship. Like the other networks presented before, the size of the circle indicates the number of documents produced, and the proximity of the labels reflects the correlation between the number of co-authored documents.

In this case, the criterion of co-authorship indicates the collaboration between authors in the development of the articles. It is possible to note three main clusters. The red one is represented by 13 items, or authors, where the most productive author is Melnykovych Mariana with 10 documents, followed by Secco Laura with 7 documents. It should also be noted that most authors in this cluster are Italian. The green cluster is composed of six items and in this case the most productive author is Ludvig Alice with 12 documents, thus also proving to be the most productive in the entire network. The last cluster, the blue one, is composed of three items, where Nijnik Maria is the most active author with nine documents.

3.4. Bibliometric Analysis: Co-Occurrence

The co-occurrence analysis highlights the most frequently appearing keywords, offering insight into the core topics and research trends.

Figure 8 illustrates how often each keyword appears, with the size of the circles representing their frequency, while the links between keywords indicate how many documents they appear in together [

23]. These connections are depicted through lines joining the terms. In this case, only keywords that appeared at least three times were included in the analysis. Subsequently, repeated keywords were removed (plural instead of singular, hyphenated instead of unhyphenated), and those that were out of context were removed, leading to the identification of 51 keywords (items) grouped into seven clusters. It is important to highlight that the map shows only those items that are interconnected.

At first glance, we can see that the central node is represented by “social innovation” (appearing 90 times), followed by “rural development” (40). This node seems to act as a bridge to “rural areas” (22), demonstrating the important role that social innovation can play in the development of rural areas. Other keywords close to the center of the map and with significant networks are “governance” (24), “challenges” (9), “resilience” (7), “policy” (15), “sustainability” (17), “entrepreneurship” (11), “management” (12), and “agriculture” (12). Slightly behind these, but still representing an important node, we find “innovation” (15). Analyzing each individual cluster, we can see that the “red” cluster with 13 items is the largest. Within this, five keywords stand out: “agriculture,” “management,” “innovation,” “sustainability,” and “entrepreneurship.” This highlights the fact that the agricultural sector undoubtedly represents a central aspect of social innovation in rural areas. Also in the red cluster are keywords that are slightly more distant but may represent important topics for research and connection, such as “ecosystem services,” “sustainable development,” “strategies,” “transitions,” and “living lab.” The words highlighted in this cluster demonstrate the significance of the agricultural sector as a key aspect of social innovation in rural areas. The synergistic interaction between agricultural practices, resource management, and innovative processes connected with sustainable development underscores an agricultural development model capable of integrating social, environmental, and economic values to develop rural areas. On the opposite side is the “green” cluster, consisting of eight items. It brings together concepts that are closely linked to the management and promotion of rural areas, with the most representative items being “rural development,” “governance,” and “policy.” Continuing with the description in descending order of cluster size, we identify the “blue” cluster with seven items. This cluster focuses on the collaborative dynamics that characterize social innovation practices. Among the highlighted words, we find “cooperation,” “collective action,” and “empowerment.” The word “forestry” is also present, demonstrating how the initiatives considered by the search string can be placed in natural and environmental contexts specific to certain areas. The terms in this cluster highlight how forestry, for all intents and purposes, is part of a broad socio-ecological resilience framework, where environmentally sustainable practices are accompanied by a greater ability to respond to the socio-economic needs of a territory and its community. Next, it is possible to identify three clusters, each containing six items. The “yellow” cluster emphasizes once again how social innovation involves participatory and community-based practices with strong links to capital, with the aim of promoting the resilience of rural areas, especially marginal ones. The principal words that comprise the cluster are “resilience,” “community,” “participation,” and “social capital.” Next, it is possible to identify the “purple” cluster, consisting of keywords such as “rural areas,” “embeddedness,” “digitalization,” and “smart villages.” This cluster demonstrates how technological innovation is a fundamental aspect for rural areas and, at the same time, how it can be promoted by cases of social innovation closely linked to local contexts. The penultimate cluster is the “light blue” one, where the central node of the entire map is located: “social innovation.” This is related to other words, such as “challenges,” “co-production,” and “migration,” which highlight the fundamental role of social innovation in addressing challenges and changes in rural areas. The last cluster is the “orange” cluster with five items. In this case, the most representative words are “growth,” “social enterprise,” and “economy,” indicating how social innovation can also be a source of economic and inclusive growth.

Figure 9 represents the overlay visualization of the co-occurrence network. The different colors of the items indicate the average year of publication of the different research topics.

In general, the average time frame is recent, concentrated between 2020 and 2023. Darker colors (blue) indicate the earliest topics studied, which include subjects such as “management”, “ecosystem services”, and “living lab”. At the same time, the brighter colors (greenish to yellow), representing most of the map, highlight the newest areas of interest within the scientific community. In this case, it is possible to locate keywords such as “social innovation,” “rural areas,” “networks,” and “social capital,” up until items in yellow such as “agency,” “health,” and “rural communities.”

3.5. Bibliometric Analysis: Citation

Figure 10 illustrates the citation map created by VOSviewer for the journals (a), authors (b), publications (c), and countries (d). The size of the circles represents the number of documents for figures a, b, and d, while for figure c it represents the number of citations. Closeness indicates how frequently they cite each other. Documents with at least one citation were included; sources, authors, and countries with at least one document were considered. In this case, unlike co-author and co-occurrence maps, not only are the networked elements presented but also all clusters. Since the analysis software is currently unable to cluster them all and present a representative image, all the elements analyzed have been reported to provide as complete a picture as possible, where, highlighted in color, we determine the most important networks. The

Journal of Rural Studies is the source with the most citations (432), followed by

Sustainability (427) and

Sociologia Ruralis (384); this group is followed by the journal of

Forest Policy and Economics (241). The high number of citations from authoritative sources emphasizes the central importance of these issues in current research debates. Bock Bettina (290) is highlighted as the author with the highest number of total citations, followed by Nijnik Maria (257), Ludvig Alice (248), Melnykovych Mariana (224), Zivojinovic Ivana (181), and Secco Laura (172). To these authors also belong some of the documents with the highest number of citations, in line with the previous results shown in

Figure 7. The network of items will expand in the coming years due to the growing number of searches in these areas. Following the analysis of country productivity, Italy (47 documents published) represents the country with the most citations (582), followed by the Netherlands (11 documents) with 538 citations, and Spain (23 documents) with 465 citations. These results further confirm that Europe is currently the focal point for research in these areas.

4. Discussion

This section discusses the key findings of this study, highlighting significant results about the main authors active in social innovation within rural areas, the countries where these aspects are most researched, the principal research topics, and the role of agriculture in social innovation initiatives in rural areas.

Based on the productivity measurement and the VOSviewer analysis results, research on social innovation in rural areas is gaining increasing attention across various fields. The larger node on the map highlights the central theme of social innovation, around which the primary connections radiate.

Figure 3,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 indicate that these topics are primarily discussed within the European context, with Italy, Germany, and Spain serving as the main contributors. These nations are represented by relatively recent studies, highlighting their significance and prominence during this historical period. Additionally, it is noteworthy to see the inclusion of two South American countries, Colombia and Brazil, in these maps. While these countries do not constitute the core of research in these fields, their presence underscores the growing global interest in social innovation practices in rural areas. Social innovation is vital in rural areas of developing countries because it addresses gaps in healthcare, education, energy, and livelihoods where traditional systems often fail. Through the engagement of local communities, the utilization of cost-effective technology, and the promotion of sustainability, social innovation empowers individuals, enhances inclusive economic growth, and advances critical development objectives such as poverty alleviation and climate resilience [

25]. Prior to any political discourse, an academic and scientific dialogue among various countries and continents presents a valuable opportunity.

Figure 7 illustrates co-authorship among authors, revealing a generally strong interconnection among them. The resulting network indicates considerable collaboration, particularly within the “red” cluster, which is primarily composed of Italian authors. Comparative studies between different European countries are already available and represent evidence of collaboration between authors of different nationalities and backgrounds [

9,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33]. In other cases, it is important to highlight that there is comparison [

34] and collaboration at the trans-continental level [

35].

Figure 8, representing the analysis of co-occurrence, is the tentative response to “RQ1: What are the main research topics involving the concepts of social innovation and rural areas?” In this regard, the division of clusters has already demonstrated how broad and diverse the topics involved are. Nevertheless, it is possible to identify common threads that can serve as a guide and provide valuable assistance in interpreting the complex relationships between social innovation and rural areas. Four keywords represent the main sectors involved, which can be identified as health, digitalization, agriculture, and forestry. The first two aspects reflect the scarcity of services and the lack of social and technological infrastructure which rural residents may experience [

36,

37]. In terms of health, particular attention is paid to the well-being of the most vulnerable and the elderly [

38,

39,

40] and, in certain specific cases, the welfare of farmers [

41] and how forms of social innovation that directly involve communities and their needs can develop in response [

42]. As proof that these challenges facing rural areas can be addressed using local resources, there are several cases in which agricultural resources are being used to develop projects promoting mental health and social inclusion. In this regard, some examples worth highlighting are the cases of social farming [

43,

44,

45,

46], where agricultural environments and activities become tools for inclusion and therapy.

The field of digitalization is a critical issue for rural areas in Europe and elsewhere, which in many cases lack adequate Internet connectivity [

36]. Consequently, its implementation, particularly in cases of digital social innovation characterized by bottom–up participation, learning, and empowerment, represents an opportunity to promote development in rural areas, generating impacts that go beyond individual cases of implementation [

47,

48]. The adoption of advanced digital technologies and their appropriate applications, such as in precision agriculture, water purification, or mobility and healthcare can be a source of sustainable development for rural communities [

47,

49]. Furthermore, the digitization of rural areas, especially the most marginal ones, requires the participation of all stakeholders, thus creating new knowledge networks [

50].

The co-occurrence map in

Figure 8 also helps us find an answer to the question “RQ4: Is agriculture part of social innovation initiatives in rural areas?”. The agricultural sector shown on the map is part of a large cluster.

Figure 8 (the co-occurrence map) reveals the existence of a complex, interconnected ecosystem in which social innovation simultaneously manifests itself as a response to economic and environmental needs and also as a tool for social cohesion and territorial development. In this context, agriculture plays a multifaceted role that extends beyond food production, becoming a space for social experimentation. Thanks to its connections, represented in

Figure 11, this item extends strongly into other clusters, demonstrating a remarkable range of relationships.

In response to our research question, agriculture appears to play a central role in social innovation in rural areas. The item “agriculture” shows strong connections with its cluster but at the same time branches out to all the others on the map. It is connected directly to “social innovation”, which represents the central node of the map. This highlights the integral role of agriculture in social innovation processes, and vice versa [

51]. Furthermore, “agriculture” has very strong links with “sustainability”, “innovation” and “sustainable development”. The proximity of these topics highlights how economic, environmental, and social aspects are strongly linked to the concept of sustainable development and social innovation in the literature [

52]. The agricultural sector is an example of this innovative aspect, which in turn represents a major challenge. Forms of social innovation are certainly a driving force for the implementation of these sustainable directions. As an example, agroecological farming practices are recognized as potentially significant, as they demonstrate the ability to integrate social and environmental aspects. They are characterized by agricultural entrepreneurs with a strong ethical commitment, aspirations for environmental sustainability, and a better quality of life [

53]. Moreover, in the agricultural sector, sustainable development directly involves social innovation practices, such as multi-stakeholder collaboration. Examples include collaboration between farmers and local decision-makers to create alternative food networks, such as community-supported agriculture [

54], and opportunities or collaboration between universities and wine producers to facilitate sustainable processing in rural areas [

55]. These considerations also reinforce and justify the link between the terms “agriculture” and “networks”, demonstrating that the involvement of multiple stakeholders is a crucial factor for the implementation of social innovation initiatives [

4]. These networks foster community involvement, food equity, and sustainability by bolstering local economies, minimizing environmental damage, and empowering individuals to contribute to the development of equitable food systems. In addition, the links associated with the term “agriculture” also emphasize the significant role of politics and associated implementation tools, such as the

Liaison entre actions de développement de l’économie rurale (L.E.A.D.E.R). These tools can promote social innovation in rural areas by encouraging different stakeholders to collaborate on joint planning, enabling the agricultural sector to become part of multisectoral networks [

56]. Although other items in

Figure 11 appear to play a more marginal role, they can still provide valuable insights into highly topical concepts. The term “ecosystem services” highlights the importance of a multifunctional agricultural sector that addresses not only primary production but also social and environmental issues. It also demonstrates how participatory approaches that facilitate recognition of these aspects can facilitate agroecological transitions within the agricultural sector [

57]. Social innovation in agriculture improves ecosystem services by fostering sustainable practices such as agroecology, community-driven research, and social farming. These strategies safeguard biodiversity, enhance soil and water quality, and fortify rural communities through inclusive, collaborative solutions that link individuals, ecosystems, and food systems.

Figure 11 also illustrates some models that could encourage social innovation in these sectors. Among the listed items, we find “living lab” and “rural hub”, for example. Although there is no commonly accepted definition of living labs, they can generally be recognized as real spaces for research, development, and innovative participatory activities that use multidisciplinary approaches and promote the co-creation paradigm [

58]. These realities can be applied in various contexts, including agriculture, to promote the adoption of socio- and agro-ecological principles [

57]. Rural hubs are centers that promote collaboration between farmers, helping them to tackle common problems and challenges together [

6,

59].

The term “forestry” is among the items that are related to the term “agriculture” but remain graphically distant, although the two sectors are deeply interconnected and interdependent. To pair them, it is important to highlight the growing focus on forms of social innovation that characterize agriculture and forestry in many rural areas, which share territories, natural resources, and social dynamics [

9,

60]. Furthermore, as shown in

Figure 12, the item “forestry” is also linked to the terms “collective action” and “cooperation”.

These links demonstrate that forest resource management is often a collective process involving various community members in a context of social innovation [

6,

61,

62].

In fact, the items “agriculture” and “forestry” share a particularly interesting link, namely “community”. This connection reminds and reinforces participatory and collective approaches that can characterize both sectors. Agricultural and forestry activities can act as real drivers for social cohesion, enhancing the social and territorial capital available. The community emerges as an entity capable of self-determination and of managing its own resources. In this regard, it is important to highlight that there are various initiatives of social innovation based on community mobilization that are spreading across Europe [

63,

64]. One of these is community cooperatives, examples of which can be found in Germany [

65] and in Italy [

66]. In both cases, there is no single definition of these entities. In Italy, there is no national law regulating them, but there are various regional laws [

67]. They are first and foremost cooperatives [

68,

69]; Sforzi and Tellarini [

70] say that community cooperatives represent a model of social innovation in which citizens serve as both producers and users of goods and services, taking on the dual role of entrepreneur and enterprise. These cooperatives are locally rooted economic entities, established by people to generate goods and services across various sectors, with the goal of improving the community’s economic and social well-being. They represent a resilient model capable of effectively addressing the current needs of rural areas, thanks to their ability to internalize social challenges, employment issues, and emerging needs [

71]. They can be engaged in various activities, even simultaneously, including new models of multifunctional and social agriculture. Agricultural resource use is particularly combined with social activities and land protection in response to a broader welfare system and to promote local development. This recognizes and enhances the knowledge, values, and natural and material assets that characterize the heritage of the primary sector [

66]. By promoting agriculture that generates social wealth and can be combined with other services distributed throughout the territory, community cooperatives take on new functions and activities necessary to address social change and structural constraints in rural areas [

71].

5. Conclusions

The aim of this study was to conduct an extensive literature review alongside a productivity measurement and a bibliometric analysis, utilizing mainly the VOSviewer software. The search of Scopus and WoS highlighted 178 relevant documents focused on the concepts of social innovations and rural areas. The analysis underlines that social innovation in rural areas is a heterogeneous and multidisciplinary field of research, characterized also by international collaboration. The results highlight how these topics are predominantly explored in Europe. At the same time, there are emerging contributors at the global level, in developing countries like Colombia and Brazil. The map of the co-occurrence of keywords reveals a complex and interconnected research landscape, where social innovation in rural areas is related to several sectors, such as health, digitalization, agriculture, and forestry. In this network, agriculture emerges as an important component linked to other aspects such as sustainability, innovation, and rural development. Through practices such as social farming, community-supported agriculture, agroecology, and the provision of ecosystem services, agriculture is proving to be a fertile ground for social innovation. Furthermore, local communities play a fundamental role in promoting social innovation initiatives. Particularly, community cooperatives, as a model of social innovation, are identified as an opportunity for rural areas, where, through participatory governance and multisectoral approaches, which may also include agriculture, they can effectively respond to the diverse needs of rural populations.

This study, even if purely theoretical, can serve as a valuable springboard for future research. By exploring the topic of social innovation in the context of rural development, particularly through agricultural initiatives, it is possible to achieve a sustainable and resilient future for areas often viewed as marginal or abandoned. It would be beneficial to investigate the distribution of innovative projects aimed at enhancing livability in these areas, mapping the effective practices that have already been implemented. Furthermore, if policymakers recognize the significance of social innovation in agriculture for rural communities, it will become increasingly feasible to introduce targeted policies designed to foster their development.

It is important, however, to also consider the limitations of this analysis. It should be acknowledged that, despite the rigorous selection process, the sample may not fully capture all relevant contributions to the field. This limitation is mainly due to the exclusive use of two databases (Scopus and WoS), which may overlook some pertinent sources. Also, the search string could be changed to refine or expand the research with insights from the current bibliometric work.