Parcelas de Agrado in Chile: A Systematic Review of Scientific and Grey Literature

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Historical Context and Initial Definitions

1.2. Suburban Areas: Definition and Characteristics

1.3. Research Problem, Objective, and Reading Plan

2. Materials and Methods of Research

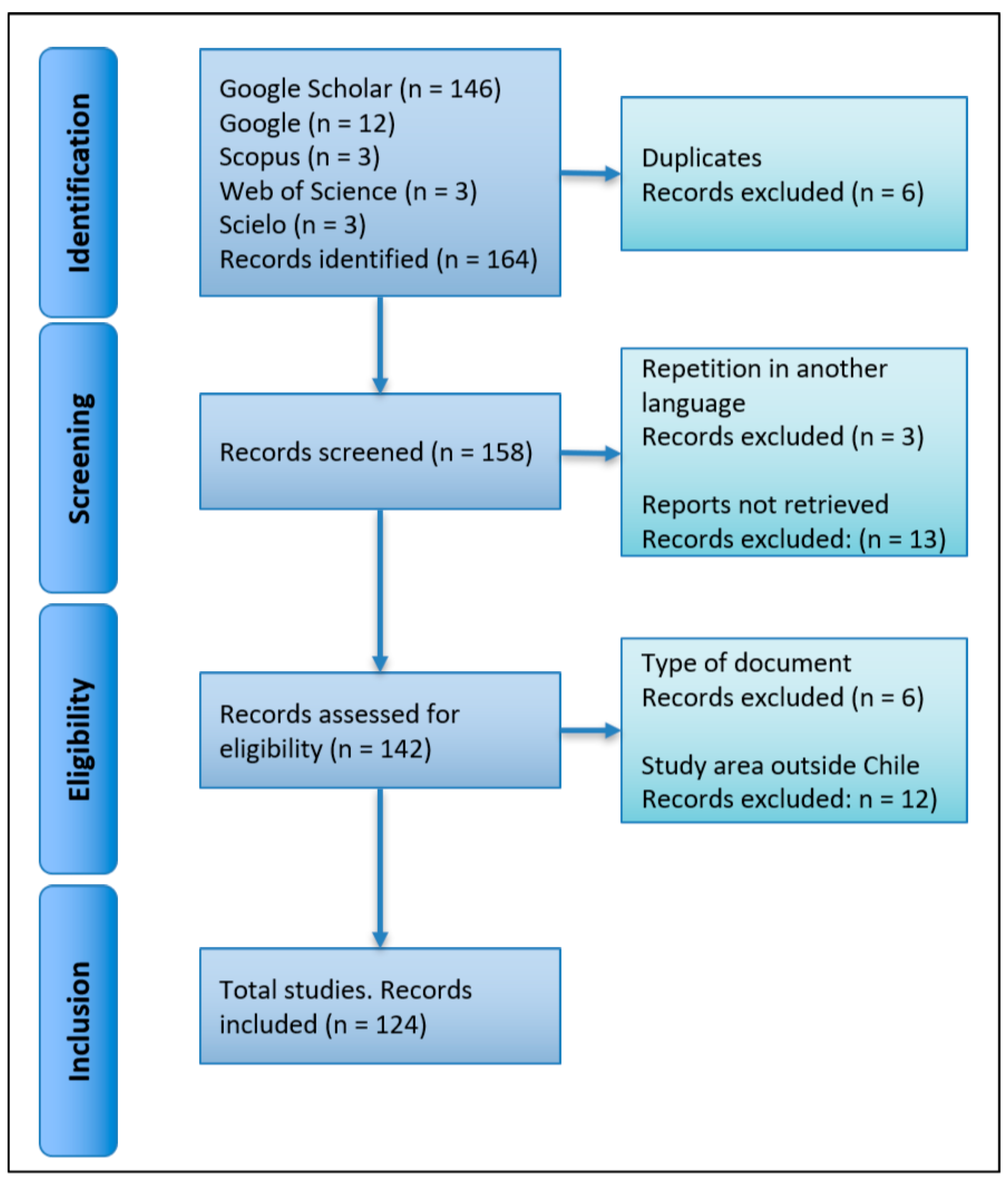

2.1. Stage 1: Data Collection and Selection Using the PRISMA Model

- That the document contains at least one mention of the concept “parcela de agrado”;

- That the type of document be: public institution reports (grey literature [30]), undergraduate dissertations, postgraduate theses (master’s and doctoral dissertations), conference papers, and scientific articles;

- That the language be Spanish, English, French, or Portuguese;

- That the study be applied to an area within Chile.

- That the document is of a different type than those indicated in the inclusion criteria;

- That the language is different from the four specified in the inclusion criteria;

- That it does not contain mentions of the concept parcela de agrado;

- That full access to its content is not possible;

- That the study was not applied to an area within Chile.

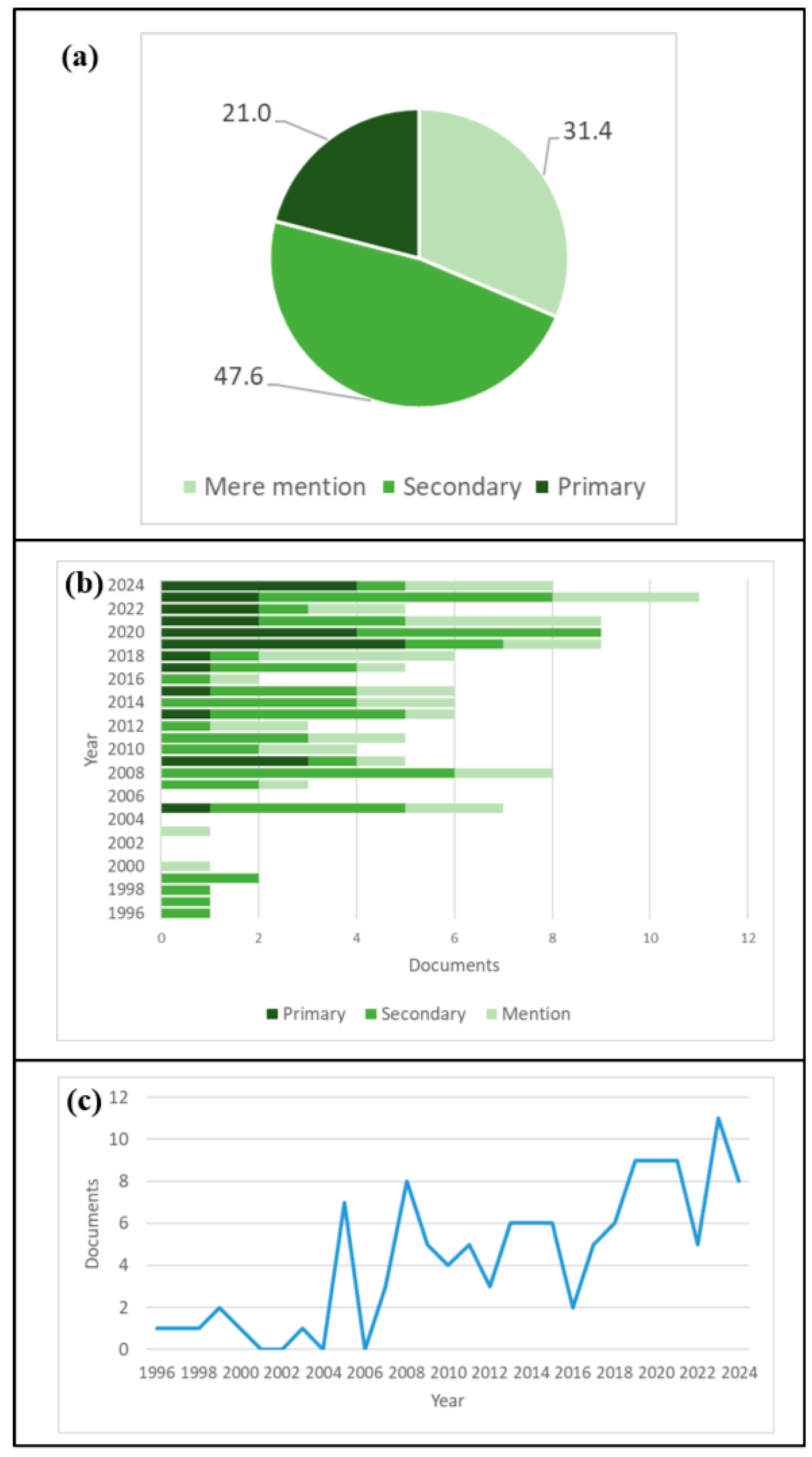

2.2. Stage 2: Definition of Categories and Descriptive Quantitative Bibliometric Analysis

- the “primary” degree addresses parcelas de agrado in depth by characterizing their main features and territorial aspects;

- the “secondary” degree addresses the topic with less attention, within broader themes that focus on rural areas;

- the “mere mention” category means that the concept of parcela de agrado appears in the document but is not further explored, as the focus is mainly on other topics.

2.3. Stage 3: Qualitative Content Analysis

3. Results: Systematic Literature Review on Parcelas de Agrado

3.1. Bibliometric Analysis

3.1.1. Degree of Relevance and Year of Publication

3.1.2. Type of Document

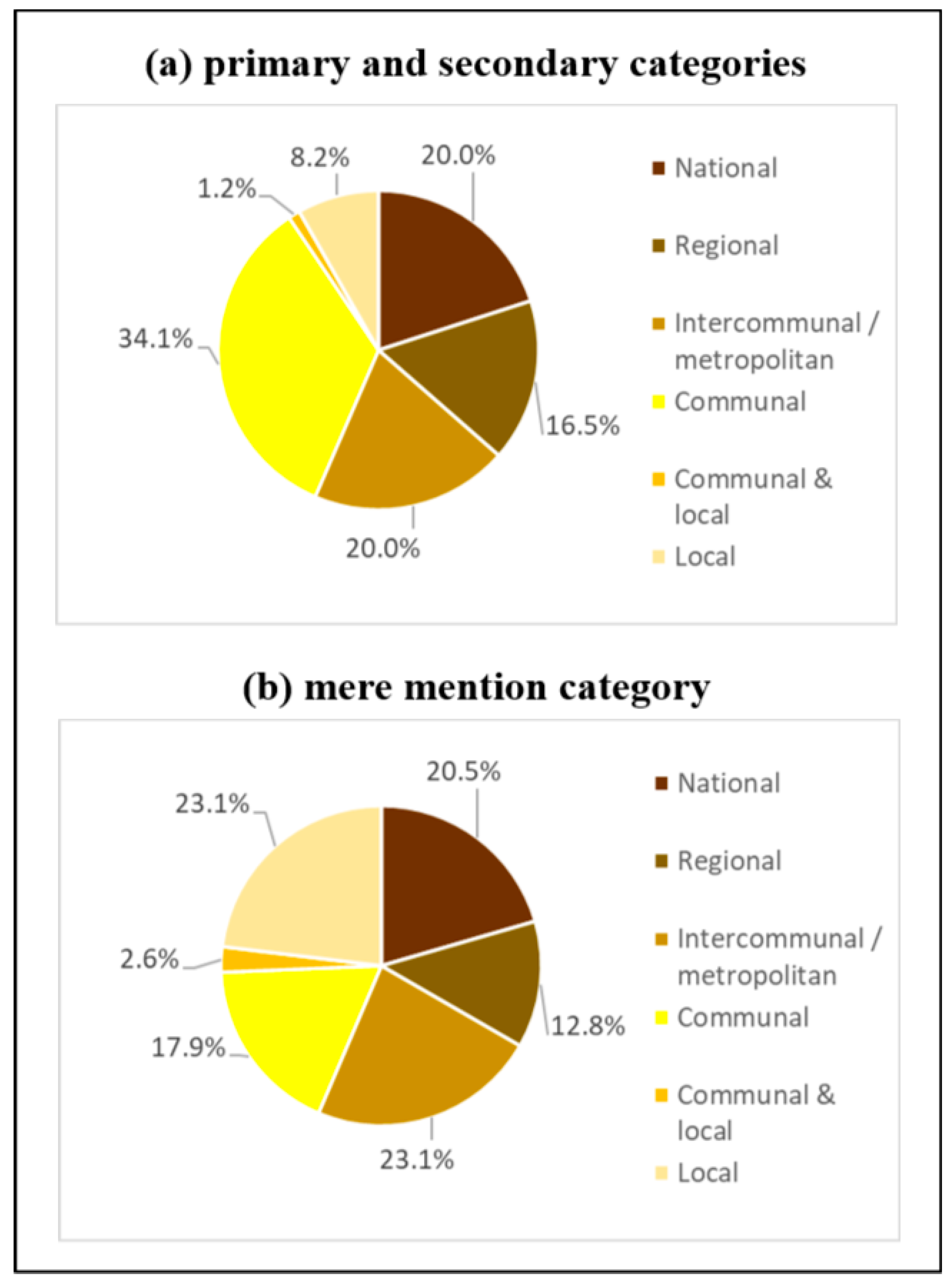

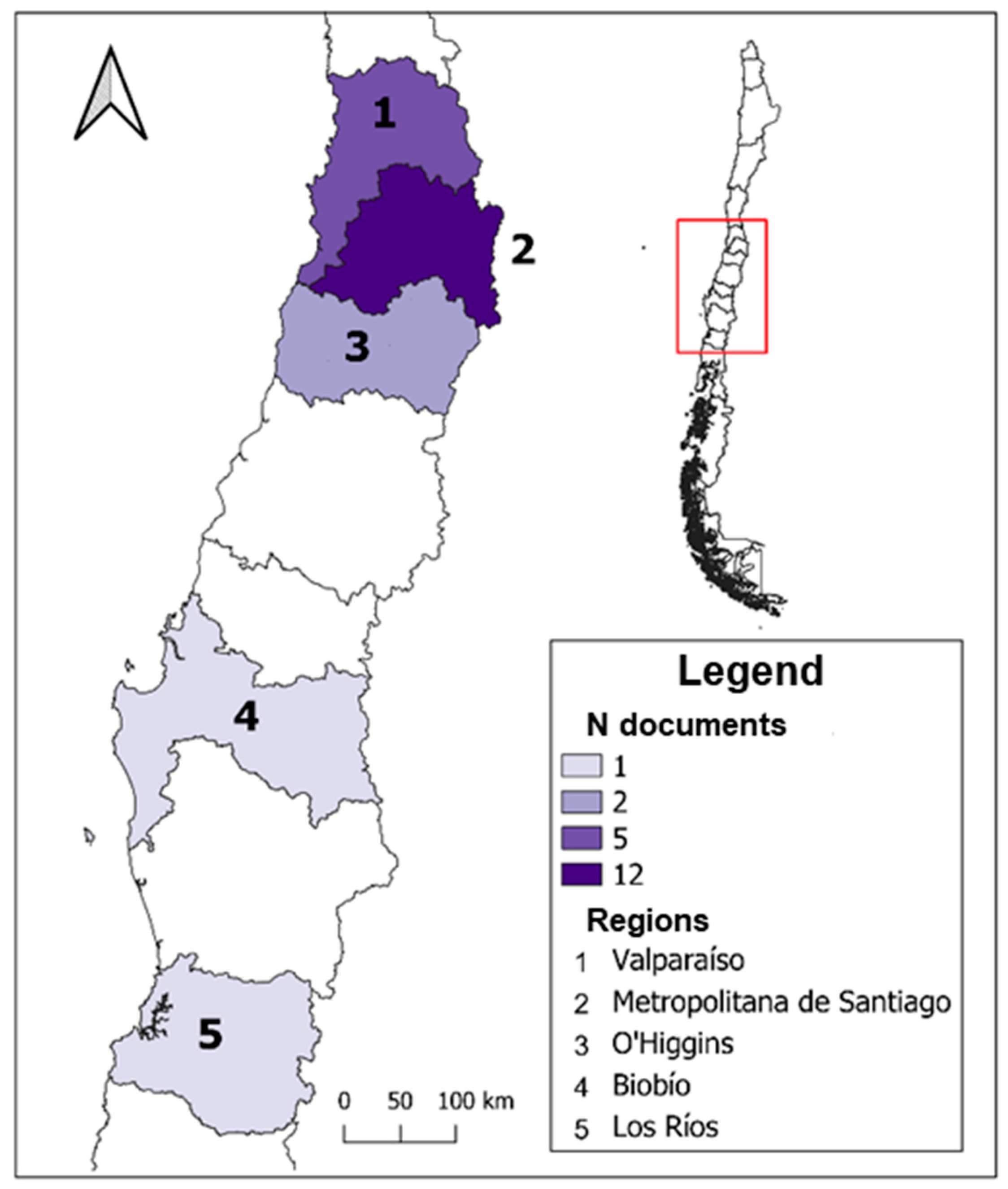

3.1.3. Geographic Scale

3.2. Analysis of Nodes and Conceptual Clusters in Titles and Keywords on Parcelas de Agrado

3.3. Qualitative Content Analysis of Studies on Parcelas de Agrado

4. Discussion and Conclusions

- Diversity and proliferation of studies;

- Facilitating elements and the proliferation of parcelas de agrado in Chile;

- Consequences associated with parcelas de agrado in Chile;

- Territorial planning as a response for the balanced development of land uses;

- Methodological approach and the use of VOSviewer;

- Conclusions and future studies.

4.1. Diversity and Proliferation of Studies

4.2. Facilitating Elements and the Proliferation of Parcelas de Agrado in Chile

4.3. Consequences Associated with Parcelas de Agrado in Chile

4.4. Territorial Planning as a Response for the Balanced Development of Land Uses

4.5. Methodological Approach: Use of VOSviewer

4.6. Conclusions and Future Studies

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mansilla, P. Los instrumentos del desorden: Estado y actores subnacionales en la producción de los espacios periurbanos. Pers. Soc. 2013, 27, 41–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubilla-Bravo, G. Rururbanización, suburbanización y reconcentración de la tierra: Efectos espaciales de instrumentos rurales en las áreas periurbanas de Chile. AGER Rev. Estud. Sobre Despoblac. Desarro. Rural. 2020, 28, 75–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Vivienda y Urbanismo (MINVU). Chile Política Nacional de Desarrollo Urbano; Ministerio de Vivienda y Urbanismo (MINVU): Santiago, Chile, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Decreto Ley, D.L. 3.516 Establece Normas sobre División de Predios Rústicos; Ministerio de Agricultura de Chile: Santiago, Chile, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Naranjo Ramírez, G. Efectos de un instrumento de planificación en el periurbano de Santiago. Caso de estudio: Comuna de TilTil. Scr. Nova Rev. Electron. Geogr. Cienc. Soc. 2005, 9, 38. [Google Scholar]

- INE Chile; IEU+T; OCUC UC. Parcelas de Agrado Desde la Perspectiva Censal y Territorial. Casos Regionales; Set de Publicaciones Post Censales (Censo 2017); Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas: Santiago, Chile, 2020; Available online: https://geoarchivos.ine.cl/File/pub/Parcelas%20de%20agrado%20desde%20la%20perspectiva%20censal%20y%20territorial_%20Regiones.pdf (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- CECT MINVU Chile. Caracterización e Impacto en el Territorio del Fenómeno de las Parcelas de Agrado; Monografía y Ensayos; Ministerio de Vivienda y Urbanismo Chile: Santiago, Chile, 2024; p. 60. Available online: https://catalogo.minvu.cl/cgi-bin/koha/opac-retrieve-file.pl?id=0407961d4b7919ccaaf9221c227ef7ad (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- Hidalgo, R.; Borsdorf, A.; Plaza, F. Parcelas de agrado alrededor de Santiago y Valparaíso: ¿Migración por amenidad a la chilena? Rev. Geogr. Norte Gd. 2009, 44, 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro Martínez, J.J. Transformaciones recientes del espacio rural tradicional de la Región Metropolitana de Santiago de Chile. Entre la agroindustria y la urbanización 1990–2017. Rev. Hist. Geogr. 2019, 41, 151–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubilla-Bravo, G.; Aranda-Cornejo, S.; Valdés-Figueroa, J. Dinámicas actuales de cobertura y uso de suelo en el periurbano de asentamientos humanos intermedios subregionales en Chile central. In Proceedings of the 4to Seminario: Experiencias Sobre Planificación y Ordenamiento Territorial en Chile, Santiago, Chile, 5 May 2023; Zenodo: Santiago, Chile, 2023; p. 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubilla-Bravo, G. A Geospatial Model of Periurbanization—The Case of Three Intermediate-Sized and Subregional Cities in Chile. Land 2024, 13, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boiteux-Orain, C.; Huriot, J.-M. Modéliser la suburbanisation. Rev. D Econ. Reg. Urbaine 2002, 73–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, R. Suburbanization and Suburbanism. In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; Volume 23, pp. 660–666. Available online: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B978008097086874044X (accessed on 30 August 2025).

- Teaford, J.C. Chapter 2. Suburbia and Post-Suburbia: A Brief History. In International Perspectives on Suburbanization: A Post-Suburban World? Phelps, N.A., Wu, F., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 15–34. ISBN 978-0-230-27639-0. [Google Scholar]

- Calenge, C.; Jean, Y. Espaces périurbains: Au-delà de la ville et de la campagne ? [Problématique à partir d’exemples pris dans le Centre-Ouest]. Geo 1997, 106, 389–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champion, T. Chapter 9. Urbanization, Suburbanization, Counterurbanization and Reurbanization. In Handbook of Urban Studies; Paddison, R., Ed.; SAGE: London, UK; Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001; pp. 143–161. ISBN 978-1-84860-837-5. [Google Scholar]

- Ekers, M.; Hamel, P.; Keil, R. Governing Suburbia: Modalities and Mechanisms of Suburban Governance. Reg. Stud. 2012, 46, 405–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, J.R. Suburbanization. Encycl. Sociol. 2000, 5, 3070–3077. [Google Scholar]

- Champion, T. Chapter 25. Urbanisation and Counterurbanisation. In Applied Geography Principles and Practice: An Introduction to Useful Research in Physical, Environmental and Human Geography; Pacione, M., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1999; pp. 347–357. ISBN 0-203-01251-8. [Google Scholar]

- Pieretti, G. Suburbanization. In Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 6468–6470. Available online: http://link.springer.com/referenceworkentry/10.1007/978-94-007-0753-5_2913 (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Lang, R.; Knox, P.K. The New Metropolis: Rethinking Megalopolis. Reg. Stud. 2009, 43, 789–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, J.R.; Molotch, H.L. Urban Fortunes: The Political Economy of Place, 20th ed.; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2007; ISBN 978-0-520-05577-3. [Google Scholar]

- Hirt, S. Suburbanizing Sofia: Characteristics of Post-Socialist Peri-Urban Change. Urban Geogr. 2007, 28, 755–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phelps, N.A.; Wu, F. Chapter 1. Introduction: International Perspectives on Suburbanization: A Post-Suburban World? In International Perspectives on Suburbanization: A Post-Suburban World? Phelps, N.A., Wu, F., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 1–11. ISBN 978-0-230-27639-0. [Google Scholar]

- CECT MINVU Chile. El Impacto de las Parcelas de Agrado en Chile: Antecedentes para la Discusión; Ministerio de Vivienda y Urbanismo: Santiago, Chile, 2024; p. 74. Available online: https://centrodeestudios.minvu.gob.cl/el-impacto-de-las-parcelas-de-agrado-en-chile/ (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- Chigbu, U.E.; Atiku, S.O.; Du Plessis, C.C. The Science of Literature Reviews: Searching, Identifying, Selecting, and Synthesising. Publications 2023, 11, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. PLoS Med. 2021, 18, e1003583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. Declaración PRISMA 2020: Una guía actualizada para la publicación de revisiones sistemáticas. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 2021, 74, 790–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado López-Cózar, E.; Orduña-Malea, E.; Martín-Martín, A. Google Scholar as a Data Source for Research Assessment. In Springer Handbook of Science and Technology Indicators; Glänzel, W., Moed, H.F., Schmoch, U., Thelwall, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 95–127. ISBN 978-3-030-02511-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Editor revista Formación universitaria La Literatura Gris. Form. Univ. 2011, 4, 1. [CrossRef]

- Waltman, L.; van Eck, N.J.; Noyons, E.C.M. A Unified Approach to Mapping and Clustering of Bibliometric Networks. J. Informetr. 2010, 4, 629–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Text Mining and Visualization Using VOSviewer. arXiv 2011, arXiv:1109.2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Visualizing Bibliometric Networks. In Measuring Scholarly Impact: Methods and Practice; Ding, Y., Rousseau, R., Wolfram, D., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 285–320. ISBN 978-3-319-10377-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirby, A. Exploratory Bibliometrics: Using VOSviewer as a Preliminary Research Tool. Publications 2023, 11, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milovanović, A.; Cvetković, N.; Šošević, U.; Janković, S.; Pešić, M. Synergies Between Land Use/Land Cover Mapping and Urban Morphology: A Review of Advances and Methodologies. Land 2024, 13, 2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moral-Munoz, J.A.; López-Herrera, A.G.; Herrera-Viedma, E.; Cobo, M.J. Science Mapping Analysis Software Tools: A Review. In Springer Handbook of Science and Technology Indicators; Glänzel, W., Moed, H.F., Schmoch, U., Thelwall, M., Eds.; Springer Handbooks; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 159–185. ISBN 978-3-030-02511-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijkamp, P.; van den Bergh, C.J.M.; Soeteman, F.J. Regional Sustainable Development and Natural Resource Use. In Proceedings of the World Bank Annual Conference on Development Economics 1990, Washington, DC, USA, 1 January 1990; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 1990; pp. 153–205. Available online: https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/239311468771020043/Regional-sustainable-development-and-natural-resource-use (accessed on 19 April 2025).

- Nijkamp, P.; Ouwersloot, H. A Decision Support System for Regional Sustainable Development: The Flag Model; Tinbergen Institute Discussion Papers; Tinbergen Institute: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1997; p. 28. Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/p/tin/wpaper/19970074.html (accessed on 19 April 2025).

- Ubilla-Bravo, G.; Chia, E. Construcción del periurbano mediante instrumentos de regulación urbana: Caso de ciudades intermedias en la Región Metropolitana de Santiago-Chile. Cuad. Geogr. 2021, 60, 275–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larrain-Suckel, J. La territorialización-desterritorialización del espacio rural: El caso de la colonización residencial en la Provincia de Chacabuco (1980–2020). Rev. Urban. 2024, 51, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina Valeria, M.A. Evaluación del Impacto Económico y Social de las Parcelas de Agrado en la Comuna de Talagante, Región Metropolitana, Chile. Master’s Thesis, Universidad de Chile, Santiago, Chile, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Valdés Figueroa, J.A. Caracterización Geoespacial y Demográfica de las Parcelas de Agrado en Diecisiete Comunas de Chile central. Memoria para Obtención Título Ingeniero en Recursos Naturales Renovables. Universidad de Chile, Santiago, Chile, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Latorre Soto, C.I. Migración por Amenidad: Nuevos Asentamientos en Zonas Rurales en la Comuna de Puerto Varas a Partir de las Parcelas de Agrado. Master’s thesis, Universidad de Concepción, Concepción, Chile, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Zerán Ruiz-Clavijo, M.P. Transformaciones Socio-Territoriales en la Interfase Periurbana de Puerto Varas: Desarrollo Privado y Planificación en el Área Periurbana; Departament d’Urbanisme i Ordenació del Territori, Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya, Barcelona, España; Santiago, Chile. 2019, pp. 1–15. Available online: https://upcommons.upc.edu/handle/2117/171640 (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Lebuy Castillo, R. del C. La Evolución del Paisaje en el Parque Nacional La Campana (Chile). Ph.D. Thesis, Universitat de Barcelona, Barcelona, España, 2017. Available online: https://diposit.ub.edu/dspace/handle/2445/185189 (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- INE Chile; IEU+T; OCUC UC. Parcelas de Agrado Desde la Perspectiva Censal y Territorial. Región Metropolitana de Santiago; Set de Publicaciones Post Censales (Censo 2017); Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas: Santiago, Chile, 2020; Available online: https://geoarchivos.ine.cl/File/pub/Parcelas%20de%20agrado%20desde%20la%20perspectiva%20censal%20y%20territorial_%20RM.pdf (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- Azócar, G.; Aguayo Arias, M.; Henríquez Ruiz, C.; Vega Montero, C.; Sanhueza Contreras, R. Patrones de crecimiento urbano en la Patagonia chilena: El caso de la ciudad de Coyhaique. Rev. Geogr. Norte Gd. 2010, 46, 85–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saa Vidal, R.; Ubilla-Bravo, G.; Rodríguez-Seguel, V.C. Asentamientos Humanos (Informe país Chile 2022). In Informe País: Estado del Medio Ambiente y del Patrimonio Natural Chile 2022; Orrego-Méndez, G., Ed.; Centro de Análisis de Políticas Públicas: Santiago, Chile, 2023; pp. 1–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorquera Guajardo, F.; Salazar Burrows, A.; Montoya-Tangarife, C. Nexos espacio-temporales entre la expansión de la urbanización y las áreas naturales protegidas. Un caso de estudio en la Región de Valparaíso, Chile. Investig. Geogr. 2017, 54, 41–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaza Chacón, F. Las Migraciones por Amenidades en Chile: Características y Consecuencias Socioespaciales. 2009. Available online: https://www.observatoriogeograficoamericalatina.org.mx/egal12/Geografiasocioeconomica/Geografiadelapoblacion/16.pdf (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- Subdirección Avaluaciones. Subdirección Avaluaciones Circular N° 15. MATERIA: Imparte Instrucciones Respecto de la Inclusión de Predios en el Catastro de los Bienes Raíces, de Conformidad con las Normas de la Ley N° 17.235, Sobre Impuesto Territorial. Deroga la Circular N° 38 de 01.07.1997, sobre Actualización y Complementación de Instrucciones para la Clasificación, Enrolamiento Y Tasación Fiscal de Predios Rurales. 2019. Available online: https://www.sii.cl/normativa_legislacion/circulares/2019/circu15.pdf (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- Abuhadba Grellet, S. Cira: Sobreproducción de Frutas en Parcelas de Agrado. Memoria Para Obtención Título Diseñador, Universidad del Desarrollo, Santiago, Chile. 2020. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/11447/3854 (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- Villavicencio Pinto, E.A. La Política de Tierras del Régimen Militar. Un Análisis a Partir de la Concentración y Subdivisión de la Propiedad Rural. Master’s Thesis, Universidad Diego Portales, Santiago, Chile, 2020. Available online: https://repositoriobiblioteca.udp.cl/TD000227.pdf (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- Silva Morales, R. Migración por Amenidad e Intereses Especiales, Efecto e Impacto en el Valor del Suelo Agrícola, en las Comunas de Navidad y Litueche. Master’s Thesis, Universidad de Chile, Santiago, Chile, 2018. Available online: https://repositorio.uchile.cl/handle/2250/153039 (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- Arredondo Mundaca, V.S. Estudio de Pre-Factibilidad Económica de Parcelas de Agrado “El Totoral” en al Quinta Región de Valparaíso. Memoria para obtención título Ingeniero Civil Industrial. Universidad Andrés Bello: Santiago, Chile, 2019. Available online: https://repositorio.unab.cl/xmlui/handle/ria/18104 (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- Jiménez Barrado, V.; Larraín Suckel, J.; Trincado Olhabé, B.; Cabrera Cona, F. Promoted Urbanization of the Countryside: The Case of Santiago’s Periphery, Chile (1980–2017). Land 2020, 9, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo Dattwyler, R.; Borsdorf, A.; Zunino, H. Las dos caras de la expansión residencial en la periferia metopolitana de Santiago: Precariópolis estatal y privatópolis inmobiliaria. In Producción Inmobiliaria y Reestructuración Metropolitana en América Latina; Pereira, C.X., Hidalgo Dattwyler, R., Eds.; SERIE GEOlibros; Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile: Santiago, Chile, 2008; pp. 167–196. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/259654117 (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- Borsdorf, A.; Hidalgo, R.; Sánchez, R. A New Model of Urban Development in Latin America: The Gated Communities and Fenced Cities in the Metropolitan Areas of Santiago de Chile and Valparaíso. Cities 2007, 24, 365–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ley 20.943 Modifica la Ley General de Urbanismo y Construcciones, para Especificar el Tipo de Infraestructura Exenta de la Obligación de Contar con un Permiso Municipal, y en Cuanto a las Condiciones que Deben Cumplir las Obras de Infraestructura Ejecutadas por el Estado. 2016. Available online: https://bcn.cl/2qngs (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Decreto 458 Aprueba Nueva Ley General de Urbanismo y Construcciones.1976. Available online: http://bcn.cl/1lz2d (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Rajevic, E. La frágil regulación del suelo rural a cuatro décadas de su liberalización. AUS Arquit. Urban. Sustentabilidad 2020, 28, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MINAGRI Chile. MINVU Chile Modifica la Ley General de Urbanismo y Construcciones, y Otros Cuerpos Legales, para Regular el Desarrollo de Zonas Residenciales en el Medio Rural. 2024. Available online: https://www.camara.cl/legislacion/ProyectosDeLey/tramitacion.aspx?prmID=17618&prmBOLETIN=17006-01 (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Ley 18.755 Establece Normas Sobre el Servicio Agrícola y Ganadero, Deroga la Ley No 16.640 y Otras Disposiciones. 1989. Available online: http://bcn.cl/1lz7q (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Ley 15.020 Reforma Agraria. 1962. Available online: http://bcn.cl/1vqcf (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Ley 16.640 Reforma Agraria. 1967. Available online: http://bcn.cl/1uv6m (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Montes Cisternas, C. A 20 años de la liberalización de los mercados de suelo. Rev. Urban. 1999, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Flores Guzmán, L.F. El Paraíso en Proceso de Subdivisión: Parcelaciones que Influyen en el Panorama de Planificación Urbana en Zonas Rurales en la Patagonia Chilena, el Caso de Levicán, Ubicado en la Comuna de Río Ibáñez, Región Aysén. Master’s Thesis, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Santiago, Chile, 2023. Available online: https://estudiosurbanos.uc.cl/exalumnos/laura-fernanda-flores-guzman/ (accessed on 12 April 2025).[Green Version]

- Resolución No 76 Deja sin Efecto Resolución No 115, de 2005 y Modifica Plan Regulador Metropolitano de Santiago. 2006. Available online: http://bcn.cl/1q8dy (accessed on 14 April 2025).[Green Version]

- Hidalgo, R.; Zunino, H.M. Negocios inmobiliarios en centros turísticos de montaña y nuevos modos de vida: El papel de los migrantes de amenidad existenciales en la Comuna de Pucón-Chile. Estud. Perspect. Tur. 2011, 20, 307–326. [Google Scholar]

- Brunet, R. La carte-modèle et les chorèmes. Mappemonde 1986, 4, 2–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunet, R. Sustainable Geography; Geographical Information Systems Series; ISTE; Wiley: London, UK; Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-1-118-55784-6. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Ubilla Bravo, G. Modelo Territorial: Sistema Síntesis de la Región Metropolitana de Santiago.Plan Regional de Ordenamiento Territorial de la Región Metropolitana de Santiago. Etapa 3: Propuesta del PROT RMS; Gobierno Regional Metropolitano de Santiago: Santiago, Chile, 2015; p. 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faliès, C. Espaces Ouverts et Métropolisation Entre Santiago du Chili et Valparaíso: Produire, Vivre et Aménager les Périphéries. Ph.D. Thesis, Université Panthéon-Sorbonne-Paris I, Paris, France, 2013. Available online: https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-00980400 (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- Díaz, G.I.; Mansilla, M.; Nahuelhual, L.; Carmona, A. Caracterización de la subdivisión predial en la comuna de Ancud, Región de Los Lagos, Chile, entre los años 1999 y 2008. Agro Sur 2010, 38, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubilla-Bravo, G. Gouvernance territoriale et politiques d’aménagement. Cas du périurbain au Chili, 1960–2015. Ph.D. Thesis, Université Paul-Valéry, Montpellier III, Montpellier, France, 2020. Available online: https://hal.science/tel-03094889/ (accessed on 6 April 2025).

- Contreras Alonso, M.; Opazo, D.; Núñez Pino, C.; Ubilla Bravo, G. Informe Final del Proyecto “Ordenamiento Territorial Ambientalmente Sustentable” (OTAS); Contreras Alonso, M., Ed.; Gobierno Regional Metropolitano de Santiago, Universidad de Chile y Agencia Técnica Alemana: Santiago, Chile, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigolon, A.; Browning, M.H.E.M.; Lee, K.; Shin, S. Access to Urban Green Space in Cities of the Global South: A Systematic Literature Review. Urban Sci. 2018, 2, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Marini, S.; Mauro, M.; Maietta Latessa, P.; Grigoletto, A.; Toselli, S. Associations Between Urban Green Space Quality and Mental Wellbeing: Systematic Review. Land 2025, 14, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Pacheco, C.B.; Villaseñor, N.R. Urban Ecosystem Services in South America: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, R.; Salazar, A.; Lazcano, R.; Roa, F.; Álvarez, L.; Calderón, M. Transformaciones socioterritoriales asociadas a proyectos residenciales de condominios en comunas de la periferia del Área Metropolitana de Santiago. Rev. INVI 2005, 20, 104–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas, S.T.; Traub, R.A. Expansión Urbana y Suelo Agrícola: Revisión de la Situación en la Región Metropolitana; ODEPA: Santiago, Chile, 2013; Available online: https://bibliotecadigital.odepa.gob.cl/handle/20.500.12650/2678 (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- Zamora, G.G.; Álvarez, J.L.; Gajardo, E.G.; Rodríguez, L.R.; Salinas, R.C. Impacto de la Expansión Urbana Sobre el Sector Agrícola en la Región Metropolitana de Santiago. Informe Final; Consultoría ODEPA; Oficina de Estudios y Políticas Agrarias del Ministerio de Agricultura, Gobierno de Chile: Santiago, Chile, 2012; p. 55. [Google Scholar]

- Escenarios Hídricos–EH 2030. Transición hídrica. el futuro del agua en Chile; Fundación Chile: Santiago, Chile, 2019; ISBN 978-956-8200-50-3. Available online: https://escenarioshidricos.cl/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Transicion-hidrica-el-futuro-del-agua-en-Chile-v.1_compressed.pdf (accessed on 6 April 2025).

- CONAF Chile. Sud-Austral Consulting SpA Diagnóstico de la Desertificación en Chile y Sus Efectos en el Desarrollo Sustentable: Alineación de los Contenidos del Actual PANCD con la Estrategia Decenal de la Convención (CNULD), la Iniciativa de Degradación Neutral de la Tierra y los Objetivos del Desarrollo Sostenible; CONAF: Santiago, Chile, 2016; p. 32. Available online: https://bibliotecadigital.ciren.cl/handle/20.500.13082/32893 (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Decreto No 469 Aprueba Política Nacional de Ordenamiento Territorial. 2021. Available online: http://bcn.cl/2qf3o (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- De la Paz Mellado, V. Uso del Suelo en el Área Rural. Acercamiento a los Casos Existentes; Asesoría Técnica Parlamentaria; Biblioteca del Congreso Nacional de Chile: Valparaíso, Chile, 2021; p. 18. Available online: https://obtienearchivo.bcn.cl/obtienearchivo?id=repositorio/10221/32383/1/BCN__Uso_del_suelo_en_el_area_rural__DEFINITIVO%20Corregido.pdf (accessed on 6 April 2025).

- Ley 21.074 Fortalecimiento de la Regionalización del País. 2018. Available online: http://bcn.cl/23seb (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Naranjo Ramírez, G. El rol de la ciudad infiltrada en la reconfiguración de la periferia metropolitana de Santiago de Chile. Estud. Geogr. 2009, 70, 205–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubilla-Bravo, G. Aprendizaje en la gobernanza territorial: Construcción de lenguaje, coordinación y acuerdos entre los actores del periurbano. Rev. Geogr. Norte Gd. 2023, 86, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GORE Valparaíso. Plan Regional de Ordenamiento Territorial. Región de Valparaíso 2014–2024; Gobierno Regional de Valparaíso: Valparaíso, Chile, 2014; Available online: https://eae.mma.gob.cl/storage/documents/04_Anteproyecto_PROT_Valparaiso_Continental_1.pdf.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Allan, A.; Soltani, A.; Abdi, M.H.; Zarei, M. Driving Forces behind Land Use and Land Cover Change: A Systematic and Bibliometric Review. Land 2022, 11, 1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, T.; Wang, L.; Xie, H.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y. Exploring the Global Research Trends of Land Use Planning Based on a Bibliometric Analysis: Current Status and Future Prospects. Land 2021, 10, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Domain | Description | Category |

|---|---|---|

| Publication | Type of publication. | Scientific article. |

| Conference paper. | ||

| Master’s thesis. | ||

| Doctoral dissertation. | ||

| Undergraduate dissertation. | ||

| Book chapter. | ||

| Institutional document. | ||

| Degree of relevance | Level of depth regarding the topic of parcelas de agrado in each document. | Primary. |

| Secondary. | ||

| Mere mention. | ||

| Geographic scale | Definition of geographic scale according to the scope of each case study. | Local. |

| Communal. | ||

| Intercommunal/Metropolitan. | ||

| Regional. | ||

| Nacional. |

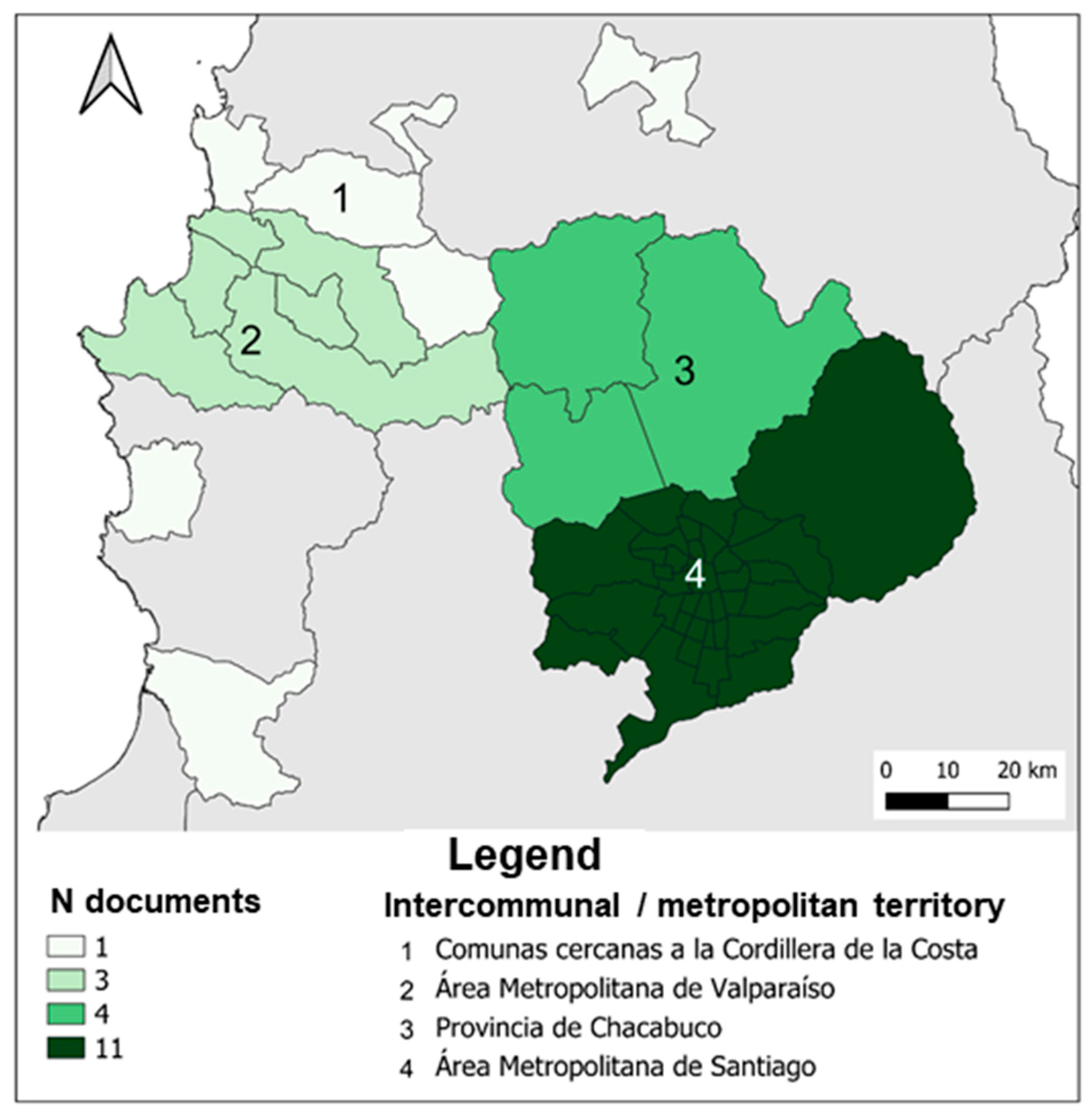

| Region | Code on the Map | Inter-Communal/Metropolitan Territory | N of Documents |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metropolitana de Santiago | 4 | Santiago Metropolitan Area | 11 |

| Metropolitana de Santiago | 3 | Provincia de Chacabuco | 4 |

| Valparaíso | 2 | Valparaíso Metropolitan Area | 3 |

| Valparaíso | 1 | Communes near the Coastal Range | 1 |

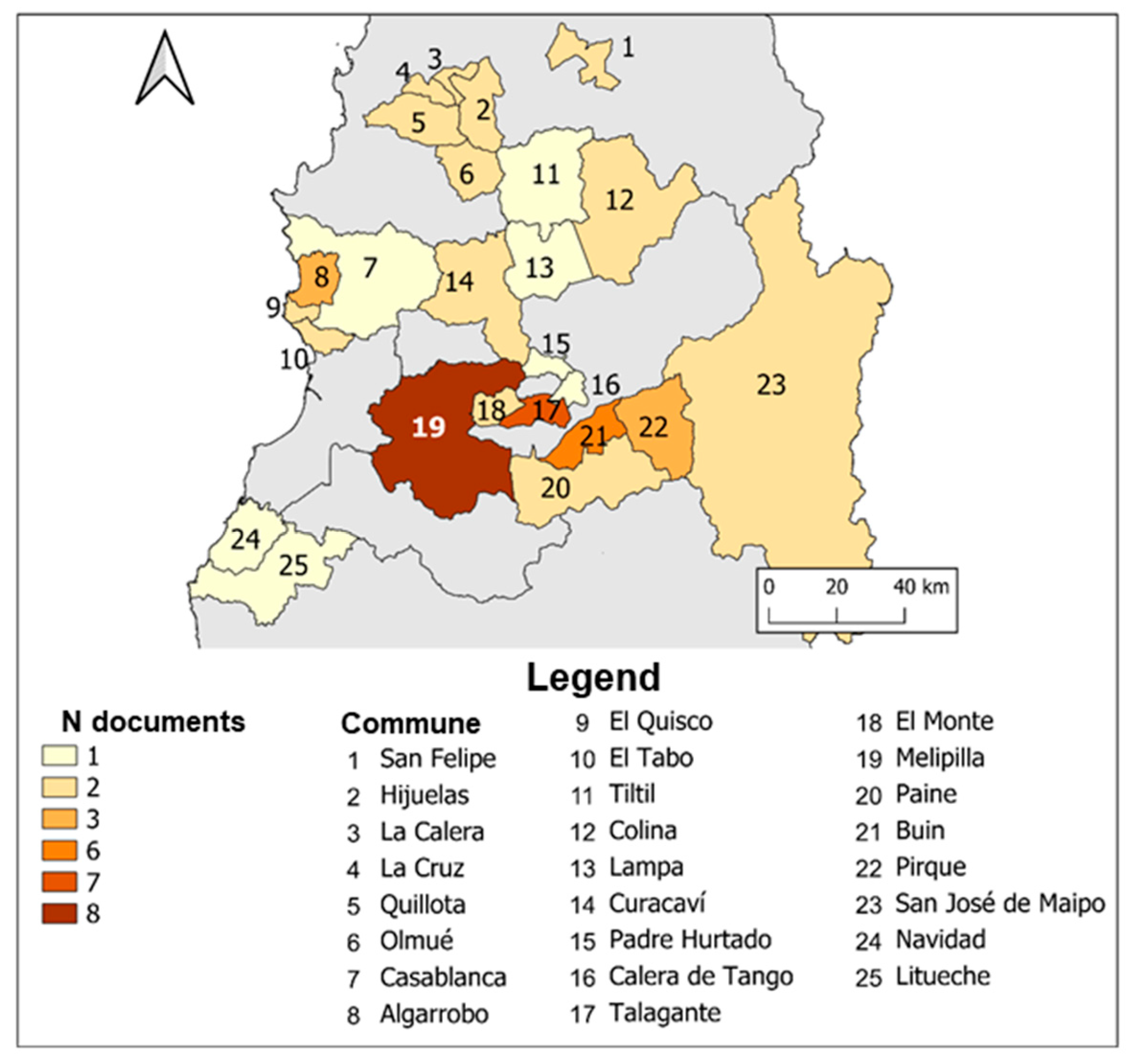

| Region | Code in the Map | Inter-Communal/Metropolitan Territory | N of Documents |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metropolitana de Santiago | 19 | Melipilla | 8 |

| Metropolitana de Santiago | 17 | Talagante | 7 |

| Metropolitana de Santiago | 21 | Buin | 6 |

| Metropolitana de Santiago | 22 | Pirque | 3 |

| Valparaíso | 8 | Algarrobo | 3 |

| Metropolitana de Santiago | 23 | San José de Maipo | 2 |

| Metropolitana de Santiago | 20 | Paine | 2 |

| Metropolitana de Santiago | 18 | El Monte | 2 |

| Metropolitana de Santiago | 14 | Curacaví | 2 |

| Metropolitana de Santiago | 12 | Colina | 2 |

| Valparaíso | 10 | El Tabo | 2 |

| Valparaíso | 9 | El Quisco | 2 |

| Valparaíso | 6 | Olmué | 2 |

| Valparaíso | 5 | Quillota | 2 |

| Valparaíso | 4 | La Cruz | 2 |

| Valparaíso | 3 | La Calera | 2 |

| Valparaíso | 2 | Hijuelas | 2 |

| Valparaíso | 1 | San Felipe | 2 |

| Metropolitana de Santiago | 15 | Padre Hurtado | 1 |

| Metropolitana de Santiago | 16 | Calera de Tango | 1 |

| Metropolitana de Santiago | 11 | Tiltil | 1 |

| Metropolitana de Santiago | 13 | Lampa | 1 |

| Valparaíso | 7 | Casablanca | 1 |

| O’Higgins | 24 | Navidad | 1 |

| O’Higgins | 25 | Litueche | 1 |

| Region | Code in the Map | Inter-Communal/Metropolitan Territory | N of Documents |

|---|---|---|---|

| Los Lagos | 10 | Puerto Varas | 6 |

| O’Higgins | 2 | San Fernando | 2 |

| Maule | 4 | Curicó | 2 |

| Maule | 6 | Constitución | 2 |

| Ñuble | 7 | San Carlos | 2 |

| Coquimbo | 1 | La Serena | 1 |

| Maule | 3 | Romeral | 1 |

| Maule | 5 | Sagrada Familia | 1 |

| Araucanía | 8 | Villarrica | 1 |

| Araucanía | 9 | Pucón | 1 |

| Los Lagos | 11 | Ancud | 1 |

| Los Lagos | 12 | Quemchi | 1 |

| Los Lagos | 13 | Dalcahue | 1 |

| Los Lagos | 14 | Castro | 1 |

| Los Lagos | 15 | Quellón | 1 |

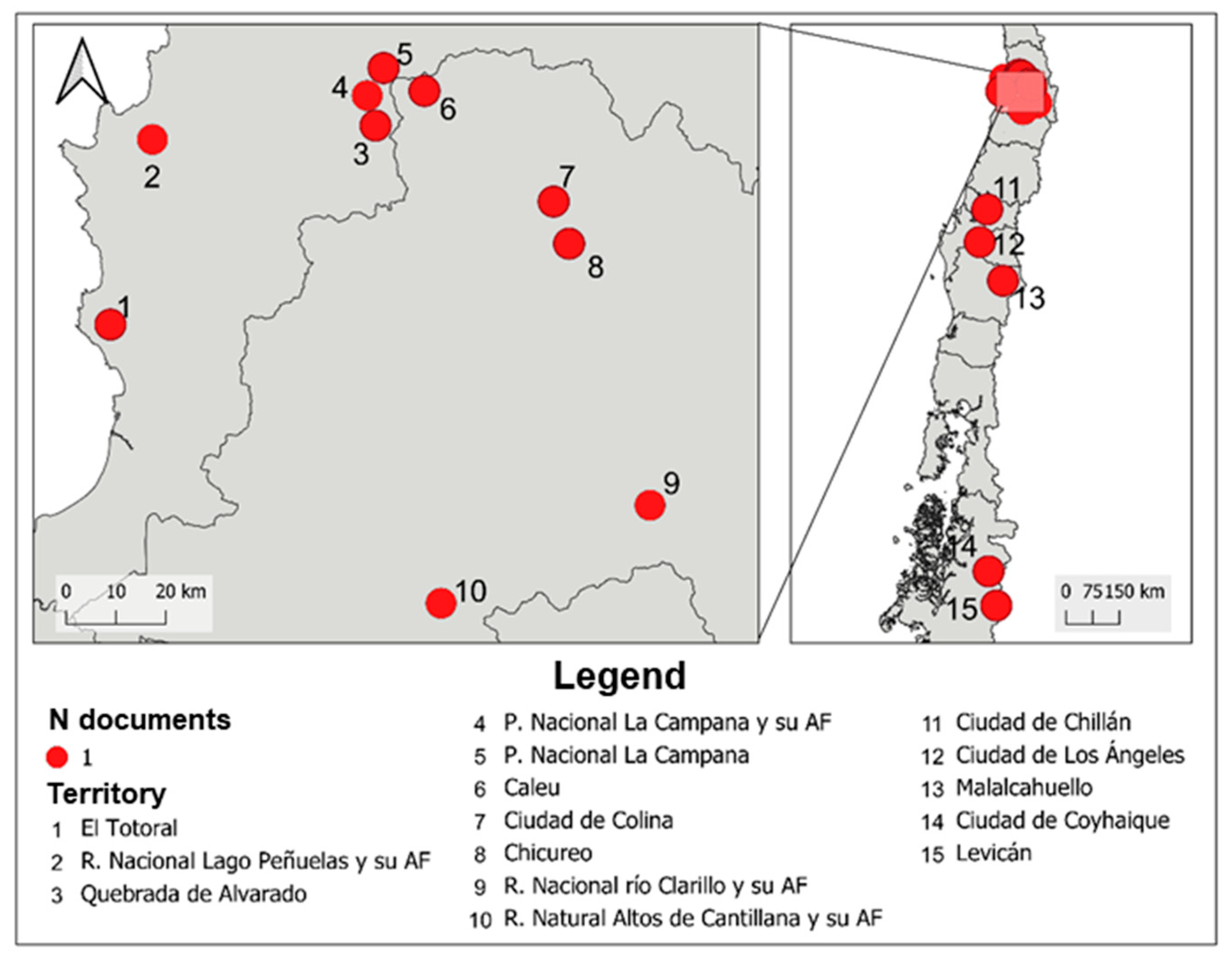

| Region | Commune | Code in the Map | Local Territory | N of Documents |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valparaíso | El Quisco | 1 | El Totoral | 1 |

| Valparaíso | Valparaíso | 2 | Reserva Nacional Lago Peñuelas and its area of influence | 1 |

| Valparaíso | Olmué | 3 | Quebrada de Alvarado | 1 |

| Valparaíso | Hijuelas | 4 | Parque Nacional La Campana and its area of influence | 1 |

| Valparaíso | Hijuelas | 5 | Parque Nacional La Campana | 1 |

| Metropolitana de Santiago | Tiltil | 6 | Caleu | 1 |

| Metropolitana de Santiago | Colina | 7 | Colina city | 1 |

| Metropolitana de Santiago | Colina | 8 | Chicureo | 1 |

| Metropolitana de Santiago | Pirque | 9 | Reserva Nacional río Clarillo and its area of influence | 1 |

| Metropolitana de Santiago | Paine | 10 | Reserva Nacional Altos de Cantillana and its area of influence | 1 |

| Ñuble | Chillán | 11 | Chillán city | 1 |

| Biobío | Los Ángeles | 12 | Los Ángeles city | 1 |

| Araucanía | Curacautín | 13 | Malalcahuello | 1 |

| Aysén | Coyhaique | 14 | Coyhaique city | 1 |

| Aysén | Río Ibáñez | 15 | Levicán | 1 |

| Cluster Color | Pivotal Concept in the Title | Other Main Concepts That Make Up the Cluster |

|---|---|---|

| 1. red | comuna. | parcela, Valparaíso, Región Metropolitana de Santiago. |

| 2. green | caso. | periurbano. |

| 3. blue | Chile (pivotal of all the system). | Región Metropolitana. |

| 4. yellow | suelo. | región, uso. |

| 5. purple | Puerto Varas. | área periurbana. |

| 6. light blue | Latin America. | gated community. |

| 7. orange | Santiago | producción. |

| Cluster Color | Pivotal Concept in the Title | Other Main Concepts That Make Up the Cluster |

|---|---|---|

| 1. red | parcelas de agrado. | periurbano, Chile, expansión metropolitana. |

| 2. green | ruralidad. | población rural, suelo agrícola. |

| 3. blue | Chili. | globalización, Plan Regulador Comunal. |

| 4. yellow | ordenamiento territorial. | planificación regional, aménagement du territoire. |

| 5. purple | periurbanización. | expansión urbana, áreas silvestres protegidas. |

| Code | Key Idea | Content Description and Source |

|---|---|---|

| A1 | Impacts of urbanization on water and soil resources. | These parcelas de agrado, originally intended for agricultural or livestock activities, must be legally regulated through an environmental assessment process due to the additional pressure they exert on the natural environment, such as soil, by increasing housing density. Particularly in the commune of Colina, they are located in areas where water availability is limited. In southern Chile, the impact of parcelas is more severe due to the scale of the projects, causing deforestation of native forests, affecting wetlands, and generally reducing biodiversity [48]. |

| A2 | Occupation of hazard-prone areas due to natural threats. | Parcelas de agrado are located in hazard-prone areas that present high fragility. According to Urban Regulatory Instruments, 8.5% (20,103 out of 236,465 ha) of the total parcela surface area is located in risk zones. At the regional level, Coquimbo has the largest surface area of rural land subdivisions in risk zones with 11,369 ha (80.46% of the regional total). It is followed by Atacama (52.15%) and O’Higgins (39.5%). In general, risk areas are distributed among various threat types: 9,285 ha are located in flood zones; 4485.8 ha in coastal flood zones; and 12,063.7 ha in mass movement zones [7,25]. |

| A3 | Impacts on high-value ecosystems and Protected Wilderness Areas. | The analysis was conducted within the Valparaíso Region. The provinces of San Felipe and Valparaíso had the highest rates of incorporation of parcelas de agrado within Protected Wilderness Areas, at 66% and 53%, respectively. At a distance of one kilometer from the edge of these protected areas, the provinces of Quillota, Marga Marga, and Petorca presented the highest percentage variations: 73%, 69%, and 32%, respectively. At the regional level, an increase was observed in all provinces, with Quillota and San Felipe showing the largest changes at 40% and 39%. This generates pressure on the ecosystems within these protected areas [49]. |

| A4 | Nature as an attraction for parcelas de agrado. | Migration occurs from urbanized areas to rural leisure areas, which are rich in landscape diversity. This is the explanation that most closely aligns with the cases of Curacaví and Casablanca. The natural attractions that draw migrants to Curacaví include various reservoirs (Orozco, Ovalle, Pitama), while in Casablanca it is the presence of coastal-access areas such as Quintay and Tunquén, where the construction of second homes in new parcelas de agrado has proliferated [50]. |

| Code | Key Idea | Content Description and Source |

|---|---|---|

| E1 | Tax system and parcelas de agrado. | Parcelas de agrado are real estate assets (subject to taxation) located in rural areas, with a surface area of 0.5 hectares and a commercial land value higher than surrounding agricultural plots, where agricultural exploitation is nonexistent or secondary. This implies that only basic-consumption home gardens are cultivated, with no commercialization [51]. |

| E2 | Productive sectors with incidence in rural areas. | A system is proposed that allows for the preservation of the harvest produced in a parcela de agrado. This will reduce crop and monetary losses per season [52]. |

| E3 | Loss of agricultural land. | Focusing on the regions of Chile’s central macrozone, a loss of agricultural land is observed in relation to the establishment of parcelas de agrado, as these grow rapidly. For example, in the Biobío Region they grew by 703% (2001–2014 period), and by 395% in the Metropolitan Region of Santiago (1997–2017 period) [53]. |

| E4 | Increase in land value due to parcelas de agrado. | There has been a constant increase in the value of agricultural land caused by the sale of parcelas de agrado in recent years. The most expensive plots are located in the central coastal subzone, parallel to the sea. Projects located in the northern part of this subzone, near Matanzas and Pupuya beaches, are more expensive than those in the southern part, mainly because an urban area is located in the north, generating greater competition in land offerings. This situation drives increased investment in the service coverage of parcelas de agrado [54]. |

| E5 | Socioeconomic and socioproductive dimension. | The Territorial Socio-Materiality Index (ISMT) is applied in localities with the presence of parcelas de agrado in 15 communes of the Metropolitan Region of Santiago. Particularly in the southern part of the commune of Colina (mainly in the Chicureo area), there is a relatively homogeneous concentration of localities with parcelas de agrado, where the predominant socioeconomic group is ABC1 [46]. |

| E6 | Economic feasibility and projects associated with parcelas de agrado. | Through market studies, the prices of parcelas de agrado are established. The economic-financial study aims to organize and structure monetary information to assess the economic feasibility from the perspective of financial outcomes, and to determine whether the construction project of parcelas de agrado is advisable and viable [55]. |

| Code | Key Idea | Content Description and Source |

|---|---|---|

| S1 | Human settlements: population, housing. | In the Metropolitan Region of Santiago, the number of dwellings in parcelas de agrado has reached 28,804, housing 85,304 people. This means they accommodate only 1.2% of the population while occupying 9.09% of the surface area. There are 2.96 people per dwelling and a very low population density (60.93 inhabitants/km2) compared to the regional average (461.75 inhabitants/km2). Peripheral communes accumulate a greater absolute population, where Pirque, Lampa, Talagante, and Colina exceed 8000 residents in these parcelas, with Colina standing out with 18,596 inhabitants [56]. Regarding the total population in parcelas de agrado, the commune of Colina has the highest number with over 18,000 inhabitants, followed by Talagante with nearly 10,000, both located in the Metropolitan Region of Santiago. In terms of the proportion of parcela de agrado population relative to the commune’s total, the same communes stand out in reverse order: first Talagante and second Colina, both around 13% and 12%. From an interregional perspective, there is a pattern of greater parcela de agrado population concentration in the Metropolitan Region of Santiago, followed by Valparaíso Region, decreasing progressively towards the south [10]. |

| S2 | Socio-spatial segregation phenomenon. | Gated communities on the metropolitan periphery give rise to the privatópolis (higher income and socioeconomic status) and are in contrast to the precariópolis (lower income and socioeconomic status), since the locations of these residential complexes tend to coincide with areas that have a higher Socioeconomic Development Index [57]. |

| S3 | Socioeconomic and socioproductive dimension. | Thanks to the Territorial Socio-Materiality Index (ISMT), the population living in parcelas de agrado in various communes of Chile was classified by socioeconomic group. A common pattern is that higher-income groups living in parcelas de agrado are located near the sea or lakes, privileged by scenic landscapes [6]. |

| S4 | Social perception regarding parcelas de agrado. | Among the main advantages associated with living in parcelas de agrado are the tranquility and ample space they offer, which allows for recreational activities. It is also noted that the attribute of security in parcelas de agrado is perceived with relatively low value [41]. |

| S5 | Other social and cultural aspects and impacts. | Like parcelas de agrado, gated communities within urban areas—enclosed by fences, walls, and gates—are not legal condominiums but resemble them and could be called de facto condominiums. They are generally the result of coordinated action by neighbors who close streets and block free circulation in order to control access, protect against crime, and exclude any form of harm or contamination [58]. |

| Code | Key Idea | Content Description and Source |

|---|---|---|

| P1 | Public institutions and governance associated with urban development. | The Regional Ministerial Secretariat of the Ministry of Housing and Urban Development, the Regional Agricultural and Livestock Service, and the respective Municipalities must oversee the regulations associated with rural properties and, consequently, review the proliferation of parcelas de agrado. More recently, Law 20.943 [59] added a new exception as the final clause in Articles 55 and 116 of the General Law on Urbanism and Construction [60], allowing the construction of facilities for health, education, security, and religious purposes whose occupancy load is under 1000 people in rural areas [61]. |

| P2 | Regulations proposed to control parcelas de agrado. | A draft bill [62] has been developed that addresses three legal frameworks through modifications aimed at modernizing and rationalizing the territorial planning system, equipping the State Administration with greater and improved tools to respond effectively to the emerging phenomenon of the proliferation of rural subdivisions. The laws to be modified include the General Law on Urbanism and Construction [60], Decree Law 3.516 [4], and the Organic Law of the Agricultural and Livestock Service [25,63]. |

| P3 | Temporal variation in rural public policy. | Since the 1960s, policy instruments were formulated that first promoted agrarian reform [64,65] and were later reversed by the agrarian counter-reform, which introduced legislation that promoted land subdivision and thus parcelas de agrado [4]. Subsequently, instruments affecting rural areas focused primarily on housing. In particular, this resulted in land reconcentration and resale to other actors who benefited from parcelas de agrado. While agrarian reform improved rural livelihoods through food security and State-provided housing, the counter-reform aimed to privatize land resources for medium and large landowners [2]. |

| P4 | Rural area regulations. | Urban policies were radically transformed in the late 1970s [3] in favor of liberalization, privatization, and the strengthening of property rights under Chile’s military dictatorship. Key measures included eliminating rules on urban boundaries, defining large areas for urban expansion, and the liberalization, subdivision, and transaction of land. Furthermore, Decree Law 3.516 [4] allowed the subdivision of agricultural land into plots as small as half a hectare, giving rise to parcelas de agrado. This decree made possible the expansion of parcelas de agrado throughout the country [66]. |

| P5 | Relationship with other public instruments. | The preliminary zoning for Levicán (commune of Río Ibáñez, Aysén Region) aims to define areas for natural conservation, residential zones promoting sustainable lifestyles, spaces for local economic activities, and community areas to encourage civic participation. This aligns with the objectives of other public policy instruments such as the Communal Development Plan, the Regional Development Strategy, the Regional Territorial Plan, and the Regional Energy Policy [67]. |

| Code | Key Idea | Content Description and Source |

|---|---|---|

| G1 | Suburban, rururban, and periurban space. | The suburbanization process began with the publication of Decree Law 3.516 [4], through which the subdivision of agricultural land into 5000 m2 lots led to the transformation of these lands. Through this decree, around 380,000 ha outside the urban boundary were subdivided into parcelas de agrado between 1980 and 2002 in the Metropolitan Region of Santiago. These parcelas de agrado are land subdivisions where the population lives in a rural environment but works in urban activities. Their main use is leisure, not agricultural production. These parcelas represent the spatial expression of suburbanization and thus correspond to suburban areas. Additionally, the modification of the Santiago Metropolitan Regulatory Plan [68] redefined the periurban areas of Melipilla, Talagante, and Buin by proposing a new urban boundary and a new regulatory category called “Mixed Silvoagricultural Interest Area”, which recognizes parcelas de agrado as a land use category [39]. |

| G2 | Geospatial representation of sociodemographic and socioeconomic aspects. | Maps are presented to depict the phenomenon of amenity migration in the commune of Pucón. Indicators such as population variation are shown, highlighting growth and expansion linked to parcelas de agrado and rural lot subdivision. An increase in the population’s socioeconomic conditions is also noted. The significant growth in buildings occurs through 5000 m2 parcel subdivisions and condominiums, connecting changes in urban morphology with amenity migration. Most amenity migrants settle outside the consolidated urban boundary in constructions within rural land subdivisions [69]. |

| G3 | Human settlements: distribution and surface area. | A geospatial representation of the dynamics of human settlements is developed, with emphasis on parcelas de agrado. The represented phenomena include urban growth from 1993 to 2011 in the Metropolitan Region of Santiago; communes with social housing developments; housing typologies in the communes of Colina, Calera de Tango, and Peñaflor; and a synthesis of parcelas de agrado, social housing, and urbanization by condition between 1990 and 2017 [9]. |

| G4 | Geospatial representation through chorems. | The geospatial and demographic patterns of parcelas de agrado in 17 communes of central Chile are represented using the chorem or chorematic technique [70,71], considering their support elements, flows, and centers [72] within each analyzed commune [42]. |

| G5 | Accessibility, connectivity, and mobility. | Travel times from the origin points (parcelas de agrado) to work centers in the Metropolitan Region of Santiago (communes of Santiago, Providencia, and Las Condes) are analyzed based on road infrastructure for motorized vehicles [46]. A map presents optimal routes to urban centers according to travel time cost for four communes: La Serena, Algarrobo, Villarrica, and Puerto Varas, located in different regions of Chile. The shortest travel times occur in communes with a greater number of urban centers located close to one another; these areas also have a higher concentration of parcelas de agrado and good road infrastructure [6]. |

| G6 | Land cover and land use: variation and distribution. | Regarding land use distribution, 78.6% (99 cases) of properties governed by Decree Law 3.516 [4] are designated for parcelas de agrado, and only 21.4% have another intended use. In 1997, 83% of properties under Decree Law 3.516 [4] were designated for parcelas de agrado. In contrast, in 1995, only 21 properties (75%) were recorded. This highlights the significance of parcelas de agrado in land use change [5]. Regarding land area, the commune of Colina has the largest surface area with nearly 15,000 ha, followed by Curicó with just over 9000 ha. At the other extreme, El Tabo and La Calera show no presence of this type of land use. In terms of the proportion of parcelas de agrado relative to communal area, Talagante stands out, with nearly half of its surface area made up of parcelas de agrado, followed by El Quisco with nearly a quarter [10]. |

| G7 | Human settlements: environment and urban services. | Residents of the city of Batuco and the parcelas de agrado located in the same area report that their development has taken place in disconnected zones with no shared vision (cases of the settlements of Lampa, Estación Colina, 18 de Septiembre, Batuco). For example, there is no transport line connecting these four sectors, and only one civil registry office exists in Lampa. As a result, there is a sense of neglect regarding urban services and environmental conditions [73]. |

| G8 | Land subdivision. | The subdivision process in the commune of Ancud affected 43,165 ha, representing 24.6% of the total surface area. For the entire period between 1999 and 2008, 80% of subdivided properties fall under the category of small properties (0–50 ha), 15% under medium properties (50–200 ha), and only 5% under large properties (over 200 ha). More than 2000 ha have lost their agricultural purpose. This reveals that soils with agricultural potential are increasingly shifting toward suburban parcela de agrado use [74]. |

| G9 | Geospatial representation of institutional and regulatory aspects. | The impact of instruments such as the modification of the Santiago Metropolitan Regulatory Plan [68] and the Communal Regulatory Plan in the periurban areas of Melipilla, Talagante, and Buin is represented through geospatial figures. The Santiago Metropolitan Regulatory Plan introduces new urban expansion categories, one of which is particularly significant: the urbanizable area with a maximum density of 16 inhabitants/ha [68], located west of the Melipilla city. Currently, this area is used for agro-industrial farms, but it could become an area for recreational parcelas. North of Melipilla’s urban boundary lies an area classified as a “Mixed Silvoagricultural Interest Area”. This indicates that the area is already used for low-density recreational parcelas de agrado, classifying it as suburban space [75]. |

| G10 | Landscape transformation and impacts. | Landscape units were developed based on landscape diagnostics during the 2010–2015 period. The expansion area of parcelas de agrado stands out as the landscape unit occupying the largest surface area within the study area. This unit is characterized by expansion into areas of native forest located in hill regions, which showed the highest vegetation fragility [45]. |

| G11 | Synthesis of territorial planning model. | Urban expansion over a significant portion of the Metropolitan Region of Santiago—both through continuous urbanization and parcelas de agrado–has occurred without an effective planning instrument, due to the high degree of land market liberalization [3] and Decree Law 3.516 [4]. It is noted that analyzing the capacity of the regional territory to sustain this proliferation of parcelas de agrado serves as input for proposing territorial planning policies [76]. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ubilla-Bravo, G.F.; Valdés-Figueroa, J. Parcelas de Agrado in Chile: A Systematic Review of Scientific and Grey Literature. Reg. Sci. Environ. Econ. 2025, 2, 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/rsee2030028

Ubilla-Bravo GF, Valdés-Figueroa J. Parcelas de Agrado in Chile: A Systematic Review of Scientific and Grey Literature. Regional Science and Environmental Economics. 2025; 2(3):28. https://doi.org/10.3390/rsee2030028

Chicago/Turabian StyleUbilla-Bravo, Gerardo Francisco, and Julián Valdés-Figueroa. 2025. "Parcelas de Agrado in Chile: A Systematic Review of Scientific and Grey Literature" Regional Science and Environmental Economics 2, no. 3: 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/rsee2030028

APA StyleUbilla-Bravo, G. F., & Valdés-Figueroa, J. (2025). Parcelas de Agrado in Chile: A Systematic Review of Scientific and Grey Literature. Regional Science and Environmental Economics, 2(3), 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/rsee2030028