Simple Summary

People often form close bonds with animals through pet ownership and wildlife tourism, yet how these relationships shape one another is not well understood. This study looks at how owning pets might influence the way people experience wildlife during a visit to the Panda Center in China. We asked over 1400 visitors to share their thoughts and feelings about their visit. Our results show that people who own pets tend to have more meaningful and frequent encounters with wildlife compared to those who do not. Even though pets were not physically present, their influence was still felt in how visitors related to animals. At the same time, the study points out that people still hold control over animals in tourism settings, even if that control appears kind or friendly. This research helps us better understand how human–animal relationships shape tourism and highlights the need to think carefully about how we treat animals—both at home and in the wild. The findings can inform future efforts to design more respectful and thoughtful wildlife tourism experiences that consider the roles pets play in our lives.

Abstract

Pet ownership and wildlife tourism are two prominent ways people interact with non-human animals in contemporary contexts. Despite this, there is a need for further exploration of the interconnections between pets, wildlife, and visitors. Utilizing an ecological-phenomenological framework, this study examines how these multispecies interactions contribute to experiences that extend beyond the human domain. This research is based on a quantitative survey of 1422 participants at the Panda Center that were analyzed using inferential statistical methods to assess differences in visitor experiences. The statistical results reveal that pet ownership and wildlife encounters mediate the environmental affordances and constraints encountered by visitors, creating a dynamic and intricate nexus among pets, wildlife, and tourists. Specifically, pet ownership is shown to enhance both the richness and frequency of wildlife encounters. Nonetheless, the study highlights that human dominance over non-human animals remains a central environmental constraint in multispecies interactions despite the adoption of a more humane approach to animal management through tourism activities.

1. Introduction

Pet ownership and wildlife tourism are prominent ways through which people interact with non-human animals in contemporary society. These diverse interactions are now firmly rooted in the tourism studies lexicon from many disciplinary contexts [1]. While there are now a handful of studies investigating the relationship between animals and tourism agents (i.e., brokers, tourists, and other stakeholder groups like government and associations), there is scant research in tourism studies on the relationship between tourism agents (especially tourists), wild and domesticated animals, as well as pet ownership.

This gap is particularly evident in the context of nature-based and wildlife tourism, which rely heavily on natural resources and wildlife populations to attract visitors. In their study of the Lukovska Spa area, Valjarević et al. [2] found that features such as topography, ecosystems, water systems, and landscape characteristics significantly enhanced visitors’ experiences. They note that tourism in such regions typically depends on relatively undeveloped natural settings. However, the authors also note that only a limited number of studies have evaluated the economic value of these nature-based attractions. Donici and Dumitras [3] conducted a literature review study on nature-based tourism research between 2000 and 2021, suggesting that tourism behavior and local communities/stakeholders have been the two main areas of focus. However, the researchers suggest that conservation responsibilities can be distributed among various stakeholders, promoting enhanced collaboration, upgrading current services, and generating positive outcomes [4,5,6] (see also). However, despite wildlife tourism often involving the direct use of animals as attractions, even fewer studies have explored how tourists’ lived experiences and interactions with wildlife contribute to value creation beyond their role as mere consumers of nature. Such highlights a significant gap in understanding the deeper value generated through these human–wildlife encounters.

A recent addition to the literature by Dashper and Brymer [7] is based on an ecological-phenomenological perspective to decenter human privileges. The authors suggest that non-human animals should be recognized as “intentional, responsive, interpreting agents” [7] (p. 403). All animate actors, Dashper and Brymer insist, are “individual embodied, active agents with their own set of intentions and individual constraints” (p. 10). Hence, all agents (pets, wildlife, and humans) can synchronize with the environment to carry out tourism activities. Based on the ecological-phenomenological framework, therefore, these actors establish their intentions and limitations as distinguished individuals, in the words of Morton [8], “solidarity” within the landscape of tourism.

The purpose of the present study is to use the ecological-phenomenological perspective to explore visitors’ experiences with non-human animals in a wildlife care organization (Panda Base). The two research questions are:

- How does pet ownership affect the emotional and cognitive responses of zoo visitors toward wildlife?

- What differences exist in the patterns of engagement with wildlife between individuals who own pets and those who do not?

With these two research questions, we aim to decenter human centrality by considering tourists as one (albeit an important) of three interactants in the pet–wildlife–human entanglement. As such, human experience can be significantly influenced by the presence of, and attachment to, wildlife and pets in multispecies tourism spaces.

Data supporting this study are based on a survey of 1422 visitors conducted at the Chengdu Research Base of Giant Panda Breeding (Panda Base). Panda Base is a renowned visitor attraction, boasting the largest population of captive-bred giant pandas in the world, with meeting giant pandas as the primary focus of the visitor experience. However, in this study, we specifically limit the wildlife encounter to free-roaming animals that are bred and live within the Panda Base (e.g., red pandas, swans, peafowls), as well as to wild animals (e.g., other birds, insects, and vertebrates) that naturally come to and inhabit the Panda Base but are not bred or managed by it. While the Panda Base affords abundant natural habitat for free-roaming and wild animals, the rationale behind this specification is that the wildlife encounter was not purposefully planned in contrast to the visitors’ search for the giant panda. Encountering free-roaming animals and wildlife share the ecological-phenomenological approach’s recognition of the role of the environment and the interdependence between actors. This animal-environmental mutuality, according to Dashper and Brymer [7], provides the foundation for investigating individual differences between animal species that move beyond a single focus on human experience. Thus, the designated questionnaire attempts to probe this mutuality through human experiences and consciousness in investigating the complex relationship between pets, wildlife, and humans.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Introduction to the Ecological-Phenomenological Approach

The ecological-phenomenological approach synthesizes two intellectual traditions, including ecological psychology and phenomenology, to better understand the dynamic ways (human) beings interact and perceive their surroundings. Ecological psychology, pioneered by J. J. Gibson and E. J. Gibson, seeks to find an embodied, situated, and non-representational approach to cognition [9], challenging traditions in cognitivism and behaviorism in three main ways: (1) the sensory stimulus is insufficient for complex perception; (2) stimuli are objective and physically independent from subjective perception; (3) perceivers of stimuli are passive recipients of external inputs. Against these mainstream theories, ecological psychology proposes a unified organism-environment system in which perception and behavior co-evolve and mutually shape each other through experience and environmental interaction. Ecological psychology prompts the key notion of affordance, which describes how the environment provides opportunities for interactions with beings through their relationship with it [7].

For example, in the traditional psychological view, a bird sees a branch and forms a mental perception of it before evaluating the feasibility of landing on it based on its size and strength. The branch is considered an objective and external condition influencing the bird’s systematic decision. In contrast, in ecological psychology, the bird perceives the branch as an affordance, namely a perch, and prepares herself for landing as she finds the appropriate flight path. The bird’s selection of flight path and her particular way of landing depends on her immediate coupling and interaction with the branch.

Phenomenology enriches ecological psychology with a subjective and first-person dimension to the individual’s interaction and perceptions of their environment [10]. Phenomenology is a philosophical branch proposed by Edmund Husserl in the early 20th century and further developed by prominent scholars, including Maurice Merleau-Ponty. Phenomenology emphasizes the embodied nature of perception and action, suggesting that individuals can introduce different meanings into their interactions with the environment [10]. Adding this phenomenological dimension to the bird perching on a branch example means that the bird’s decision to land on the branch resulted from its past experiences, current state, and the context of its flight. The bird interacted with the branch, not through a mechanical response but through a meaningful and subjective experience that the bird embodies, which allows for an expanded understanding of bird behavior.

Dashper and Brymer [7] consider constraints and affordance as two key concepts in the ecological-phenomenological perspective. While affordance in the ecological-psychological approach means opportunities for action within a given environment, constraints explore the boundaries that shape these actions and behaviors on individual, environmental, and task levels. Constraints guide “the animal to see stable and effective patterns of behavior during goal-directed activity” [7] (p. 5). For example, the individual constraints the bird might experience are her size, weight, muscle strength, bodily coordination, previous perching history, and health condition. Environmental constraints the bird needs to calculate are the branch’s stability, weather conditions, and the presence of predators. The bird’s perch can also be shaped by its tasks, such as perching for rest or safety, the time of day, and its type of landing. The bird’s subjective experience of her past, her own body, her previous interaction with branches, and her lived experience can influence how the bird perceives and approaches the branch through her bodily phenomenology.

In summary, the ecological-phenomenological perspective emphasizes the integration between animals and their environments, where the environment both affords and constrains the animals’ actions. Similarly, animals, as embodied phenomena, can also shape and influence the presence and context of the environment. As Read and Szokolszky [10] suggest, the ecological-phenomenological perspective stresses the mutualism between animal beings and the environment.

2.2. Human-Pet Relationships in the Anthropocene

In contrast to the mutualism of the ecological-phenomenological perspective, scholars have traditionally conceived pet ownership in contemporary society through an anthropocentric lens. In this theoretical strand, scholars believe that human participation consciousness will shape an animal’s interactions with people. Hence, the emergence of pets is a result of this anthropocentric dominance, even though pets can, to a certain degree, enjoy affection from their owners. For example, the prominent geographer and humanistic scholar Yi-Fu Tuan [11] states that pet-making combines dominance and affection in contemporary society. Tuan [11] (pp. 1–2) suggests that affection can mitigate and soften domination, but affection is “dominance’s anodyne—it is dominance with a human face.” Moreover, Tuan [11] explains that young children learn about this complex power dynamic with animals during their playtime; as the children care for and nurture animals, they also develop an awareness of superiority and power.

On the surface, the ecological-phenomenological perspective straightforwardly rejects Tuan’s theoretical approach, as Tuan asserts the centrality of human presence in human-pet interaction rather than a mutualism between pets and their environment. However, while Tuan’s account is often read as anthropocentric, this paper proposes a reinterpretation: Tuan’s phenomenological sensitivity to affection, spatial intimacy, and interspecies proximity can be productively re-read through a more-than-human lens. In contrast to posthumanist scholars such as Haraway [12], who emphasize co-becoming and situated ethics, or Despret [13], who foregrounds animal agency and epistemic vulnerability, Tuan remains tethered to a human-oriented emotional framework. However, it is precisely his emphasis on affection and play—as embodied, esthetic-cultural practices—that enables a reconsideration of interspecies relations in human-altered landscapes.

If we agree with Crutzen [14] (p. 13), and numerous other scholars, that we are firmly situated within the Anthropocene, we must also acknowledge that anthropocentric thinking and practice have become the lived and embodied manner of being for humans and their treatment of animals. In other words, the environment that shapes animals and their activities from an ecological phenomenological perspective is still largely anthropocentric. Hence, in pet ownership, animals interact with human-dominated environments, while the notion and experience of a pet, according to Tuan, result from the animal’s interaction with the Anthropocene. In this light, Tuan’s conceptualization of the pet lays the foundation for an ecological-phenomenological examination of the animal’s embodiment in a lived and anthropocentric environment.

Furthermore, Tuan [11] believes that it is in the esthetic-cultural realm that the exercise of the will manifests. Tuan [11] uses the example of an artist-gardener playing in their miniature gardens, who is likely to establish themselves as a figure of power through their domination of this miniature world. Tuan’s work–play dichotomy readily places tourism activities, the non-working and fun experiences [15,16], into the esthetic-cultural realm. Hence, Tuan’s [11] observation also suggests that the landscape of tourism can lead to a greater likelihood of owners’ domination over their pets through the playful exercise of their wills, while the pleasure people experience through play masks a transformed force of dominance. In other words, any intensified pleasure and affection people may experience with their pets during tourism activities indicates that the previously exploitative domination over animals has partially assumed a more humane guise. Tuan’s observation demonstrates that tourism activities can transform the human control and use of animals into a more affectionate and gentle form of domination.

2.3. Pet in Tourism Through Esthetic Domination

The endeavor to (re)place and (re)direct our attention towards animals in tourism is designed to break the anthropocentric view that has legitimized and prioritized the existence of human beings in tourism experiences [17]. Based on Tuan’s insights on human beings’ domination and affection towards pets, an ecological-phenomenological perspective suggests that tourism activities offer more than just spaces where animals and humans co-exist and collaborate. For example, Hidalgo-Fernández et al. [18] recently pointed out that families’ attachment to pets can motivate their travel plans with pets. Wei et al. [19] found out that human-pet interaction improves both travel motivation and quality of life by creating emotional and social value. Quan et al. [20] demonstrate a positive reinforcement in the tourist–pet bond during enjoyable, nature-rich travel experiences.

Nevertheless, Tuan’s [11] framework suggests that tourism provides an anthropocentric environment where human domination over animals is transformed into an effective form of control. Tourism activities facilitate this significant transformation, enabling human participants to exert stronger and more comprehensive control over animals. In contrast, animals respond by becoming beloved pets of their owners.

Such suggestions demonstrate that tourism is not an idealized landscape where equality and mutual respect are automatically established within the multispecies connection. The terrain of tourism demands careful examination regarding how dominance is transformed into human affection and enjoyment, masking the persistence of dominance beneath this benevolent facade. Beyond mere exploitation and instrumental use of animals, human–animal interactions within tourism settings underscore human desires for an alternative form of power or experience that presents itself as more humane [21,22]. As tourism offers a sphere where this alternative power dynamic is explored and enacted, it also reinforces human dominion over animals [23,24].

However, the most significant challenge that the ecological-phenomenological perspective presents in multispecies tourism is not that the tourism landscape is fundamentally anthropocentric but rather that animals have always been active participants in the tourism landscape. It is not after the “animal turn” [17] that animals emerge as active participants in tourism activities—the animals have co-evolved with tourism activities. Additionally, as active agents themselves, animals participating in tourism activities alongside humans are often made into endearing pets for their human owners [21,25,26]. It also means that animals were not voiceless as they interacted and negotiated with the human-dominated environment but that becoming pets has been the animals’ way of materializing and “speaking” with humans. This ecological-phenomenological conclusion can sound counter-intuitive and poses a significant challenge to the entrenched belief that studies need to “give some kind of ‘voice’ to non-human animals” [17] (p. 293). However, it also provides access to “animal subjects” or “animal agency” in an anthropocentric environment.

2.4. Beyond Pets: Implications for Wildlife Tourism

Wildlife tourism studies have framed the human–wildlife relationships through a range of interconnected concepts, including co-existence [27,28], conservation and stewardship [29,30], utilization and exploitation [31], habitat loss [32], climate change [33,34], and biodiversity decline [35,36]. In addition, several studies have explored human–wildlife relationships through the lens of pet attachment [37,38]. These studies typically adopt a one-directional approach, focusing on how pet ownership shapes human perspectives on wildlife. In contrast, there has been less emphasis on the inverse perspective—examining pets through interactions with wildlife. For instance, researchers have often considered pet ownership a variable influencing human attitudes and interests toward wildlife and conservation efforts. Shuttlewood, Greenwell, and Montrose [39] note that pet ownership can affect engagement with animal-related activities and wildlife management. Additionally, their empirical analysis of 220 participants revealed that pet owners are more likely to hold sympathetic attitudes toward animals and, consequently, support wildlife management strategies that benefit the well-being and welfare of wildlife. Work by Bjerke, Øsdahl, and Kleiven [40] echoes this study, showing that pet owners, compared to non-pet owners, are more likely to attend animal-related activities, feed wildlife more frequently, and enjoy the presence of other species.

Hepper and Wells [41] argue that pet ownership, as a form of closeness to animals, has been believed to play a crucial role in shaping the public’s attitudes toward animals since the 18th century. Studies demonstrate that pet ownership and animal welfare are two positively related factors [42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49]. In general, people with intimate experiences with animals (either in adulthood or childhood) are more likely to support the progress of animal welfare and well-being policies that benefit animals. Hence, Hepper and Wells [41] conclude that pet ownership in households can significantly influence the public’s attitudes toward the use of animals and suggest that including family pet ownership as a significant factor can contribute to advancements in animal welfare policies.

The benefits provided by pets also increase people’s chances of exploring nature. Identifying pets as “friends with benefits”, numerous studies have suggested positive physical [50,51,52,53,54], psychological [55,56,57,58,59], and social [60,61,62,63] returns that human individuals receive through their attachment to pets. Further studies have revealed the complex relationship between humans and various pet species. Hajek and König [64], for instance, suggest that dog owners are less socially isolated and less lonely than cat owners and individuals without pets in older adults over 65. In a survey of 41,514 adults in California, Yabroff, Troiano, and Berrigan [65] concluded that dog owners walk for leisure 18.9 min more per week than non-pet owners and cat owners. Also, male dog owners reported higher self-esteem than individuals without pets, whereas female cat owners reported the lowest self-esteem [66]. Islam and Towell [67] reviewed 11 empirical studies on the relationship between pet possession and an owner’s health and well-being, suggesting that there was little evidence supporting the positive impacts of pets on companionship. The physical and psychological benefits pets generate can mean owners have greater opportunities and interest in interacting with other animals or wildlife.

These studies highlight that, despite the inclusion of various animals, such as farm animals and wildlife, the lens through which people evaluate their relationships with other animals is their connection with pets. This suggests that pet attachment significantly shapes and influences broader human–animal relationships. On the one hand, these studies examine whether the public’s affection for pets can extend to other animals through projects such as wildlife conservation, well-being, and welfare. On the other hand, pets generally provide direct or indirect benefits to people through their linkage to nature. Pet ownership, hence, expresses the anthropocentric needs of human beings through images of nature. This approach dominates human interaction with nature. As Tuan [11] (p. 163) suggests, the modern man

“May claim intimacy with nature—with wilderness itself. But this sense of ease in wilderness is possible only because wild animals and forests are no longer threatening. Wilderness, although not yet a pet to the degree that the garden and certainly the miniature garden is a pet, nonetheless is widely perceived by modern society to be a fragile existence that needs its care and protection.”

Tuan’s idea suggests that, despite wilderness and pet ownership being perceived as distinct, the presence of wilderness is also shaped by the dynamic interplay between the politics of domination and affection. The wild resembles the pet in terms of its perceived fragility and vulnerability, on which the human being can impose their care, protection, and dominance. Indeed, as studies [37,46,68,69] have shown, pet ownership, in general, positively reinforces people’s attitudes and activities with wildlife, indicating that pet owners are more likely to extend their dominance and affection towards wildlife. While existing studies have considered pet ownership a trigger for people’s further involvement and devotion to wildlife conservation and protection, Tuan’s [11] theoretical approach shows that people can be inherently attracted to the affective emotions and the bond to nature, to which pet ownership and wildlife conservation are mere manifestations of this human need and emotion. We will further show that the ecological-phenomenological perspective supports this interconnection between pets, wildlife, and human beings.

Despite this shared dominance-affection interplay between pets and wildlife, Tuan [11] maintains that there are also nuanced differences in people’s interactions with them. For example, owners enjoy emotional and physical intimacy with pets, which also usually grants the pets a family membership [70]. In contrast, modern people’s relationship with wildlife may not involve the same physical closeness or daily interactions but is instead contextualized within the lens of conservation and ecological significance [71]. Pets occupy and linger in the minds of their owners, presenting needs for constant personal responsibility and care [11]. In contrast, the wild and wildlife are cast in a more distant and sometimes mysterious ecological framework, requiring protection and concern from the public collective awareness [72]. These studies suggest that the power interplay between humans and animals can be dynamic and complex due to their interlinked and intersected relations in a given environment. Pet ownership indicates an established pattern within which animals interact with human beings, and this framework also extends to people’s perception of wildlife. Both pet animals and wild animals have engaged with the Anthropocene through their distinct agencies and shared the landscape of tourism with their human counterparts. In the following sections, we further explore this entanglement of pet–wildlife–human interactions through a survey-based study conducted at the Panda Base.

2.5. Summary of the Theoretical Framework

Taken together, the ecological-phenomenological perspective, the emerging patterns of pet tourism, and the broader implications for wildlife invite a rethinking of how interspecies encounters are shaped by—and help shape—our environments, habits, and ethical frameworks. Through Merleau-Ponty’s conception of embodied perception and relational space, we can begin to see pet tourism not merely as leisure but as a practice that conditions human sensitivities and expectations toward other species. These embodied encounters with pets, often domesticated and anthropomorphized, form experiential templates that are transported into wildlife tourism contexts, where animals are similarly framed as approachable, manageable, and emotionally legible. As such, pet tourism becomes not only a mirror of human desire but also a generative force in configuring the tourist gaze toward wildlife. This continuum challenges the moral and practical boundaries tourists draw between pets and wild animals, revealing the porous and performative nature of species categories in contemporary tourism. Understanding this interconnected dynamic is crucial for developing ethical wildlife tourism practices that are attuned to both human perceptual habits and the autonomy of animal life.

3. Methodology

To understand the entanglements between wildlife, pets, and humans in tourism activities, the research team conducted a survey at the Panda Base. A scientific research institute established in 1987 specializing in giant panda breeding, Panda Base claims to have the world’s largest ex situ giant panda population (200 pandas as of 2023). In addition to its scientific breeding achievement, Panda Base has become the most-visited tourist attraction in Chengdu for Chinese and international tourists. On TripAdvisor, Panda Base has been listed as the top tourist attraction in Chengdu, garnering as many as 6000 reviews. About 11.9 million tourists visited the Panda Base in 2023 [73]. The Panda Base has capped its daily visitor number at 60,000 to ensure safety and enhance visitors’ experiences. Recent studies [74,75,76,77,78] have employed the term “giant panda tourism” to describe the increasing tourist interest in visiting giant pandas in animal care centers, such as the Panda Base.

The survey was collected at the exit of Panda Base in 2023. Visitors volunteered to participate in the survey, and the research team compensated participants with a small gift (a giant panda magazine or a giant panda keychain). The survey was designed with the help of Wenjuanxing, a Chinese professional website that distributes and organizes online surveys. Wenjuanxing issued a QR code for the survey, which was printed out and allowed tourists to access the questionnaire on their mobile phones. The online system ensured that all submitted and recorded surveys were complete. Consistent with the research team’s previous data collection experience at Panda Base, the majority of the participating population consisted of young people under 40 and females. Young people were more interested in the survey due to their greater exposure to mobile technology and more advanced internet literacy compared to the older generation. The researcher working at Panda Base learned from the ticketing system that more female tourists were visiting the place than males. This knowledge justified the larger number of female participants in each of the surveys the research team had previously conducted at Panda Base.

The survey began with an Informed Consent form that detailed the purpose and process of the survey. The participants were asked to “Agree” or “Disagree” with the listed requirements in the consent form. For participants who disagreed, Wenjuanxing would end the survey. All data were collected anonymously, and the Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Protection of Personal Privacy excluded the need for an ethical committee’s support on an anonymous questionnaire like this one. However, the design and distribution of the questionnaire strictly followed the Declaration of Helsinki to ensure the privacy and autonomy of each participant.

A total of 1440 questionnaires were collected. Eighteen records with unrealistic age numbers (e.g., older than 90 years or younger than 10) were excluded from the sample, leaving 1422 valid answers. This criterion of exclusion was based on the researcher’s on-site data collection process, as the participation of very young children and older people was rare. These entries were flagged during the data quality checks as potentially indicative of data entry errors or misreporting. The questionnaire had three sections. The first section collected demographic information (gender, place of origin, educational background, and first-time versus returned visitors) from participants. The second part included eight Likert-scale questions (rated on a 1–5 scale, with 5 indicating the highest rating—most satisfied, happiest, etc.) that asked visitors to evaluate their experiences at Panda Base. The first three questions evaluated the biodiversity, natural environment, and visiting experiences of Panda Base, and the other five questions assessed the enjoyment of nature, the calming effect, the willingness to learn about wildlife, the willingness to donate, and the willingness to become a wildlife conservation volunteer at Panda Base. The last section examined participants’ experiences with animals—whether they had encountered wildlife or kept pets at home. Specifically, the wildlife encounter in this study referred to visitor–animal interactions with free-roaming or captive animals, excluding giant pandas, at Panda Base. The median time it took visitors to complete a questionnaire was 54 s. The collected data were stored in a saved file, which the researcher downloaded for further analysis in SPSS Version 26 Mac. On SPSS, the researcher performed descriptive analysis to allow the underlying patterns of the sample to surface.

4. Data Analysis

To display our results holistically, we took the following steps: First, a summary of the dataset, based on the demographic characteristics and visitation experiences of Panda Base, was displayed to introduce the samples included in this study. Frequency and percentage were the primary statistical methods in this section. Second, pet ownership and wildlife encounters were further explored as two independent variables in the dataset. T-tests were employed to determine whether pet ownership and wildlife encounters yielded distinct results in visitors’ experiences (measured using a 5-Likert scale) at the Panda Base. Although our data were based on 5-point Likert scales and not normally distributed, we used independent sample t-tests due to our large sample size (n > 1000), which ensured robustness through the Central Limit Theorem. Prior research has shown that t-tests and Mann–Whitney tests yield similar power and acceptable Type I error rates for Likert items, even under skewed distributions [79]. Third, the intersection between pet ownership and wildlife encounters was studied through the Kruskal–Wallis test. We used boxplots to inspect the distribution of the data and found relatively similar distribution shapes across groups, supporting the assumption of the Kruskal–Wallis test that differences were due to medians rather than distribution shape. Lastly, we delved into the details of pet ownership, including the various types of pets owned by visitors. Kruskal–Wallis and Chi-square tests were used to explore this dimension.

4.1. Demographic Profile and Visitation Summary

Table 1 provides an overview (frequency and percentage) of the participants based on their demographic characteristics and visitation experiences at Panda Base. The sample is consistent with previous survey samples collected from Panda Base. For example, females (67.4%), visitors coming for vacation (71.4%), and young people (Agemedian = 28.00) dominated the respondent pool. More than half of the participants had a college degree or more. On average, tourists spent 3–4 h at the Panda Base, and 13.9% of tourists revisited the place.

Table 1.

Demographic profile of the sample.

4.2. Pet Ownership and Wildlife Encounter as Independent Variables

Table 2 shows that pet ownership and wildlife encounters at Panda Base are positively related (r = 0.072, p = 0.007), and significant discrepancies are observed between the groups (χ2 = 7.273, p = 0.007). Specifically, pet owners were more likely to have wildlife encounters (48.87%) than non-owners (41.39%). Non-owners (58.61%) had fewer wildlife encounters than pet owners (51.13%). The table suggests that pet ownership influences visitors’ interactions with wildlife, meaning that pet owners, as tourists, were more likely, consciously or unconsciously, to search for interactions with free-roaming wildlife at animal care organizations such as the Panda Base.

Table 2.

Wildlife encounters and pet ownership as independent variables.

Table 3 presents the t-test results of visitors’ evaluations of their visit experiences at Panda Base based on pet ownership. The results show that pet ownership did not significantly influence people’s overall visitation experience at the Panda Base. Non-owners (m = 4.52) believed that they enjoyed nature significantly more (p = 0.024) than pet owners (m = 4.40).

Table 3.

t-test on visitation experiences evaluation based on pet ownership (PO/NO).

Table 4 shows that wildlife encounters have a significant influence on tourists’ visiting experiences at the Panda Base. For example, visitors’ enjoyment of nature (p = 0.036), feelings of calmness (p = 0.001), willingness to donate (p = 0.047), and willingness to volunteer (p = 0.009) were significantly higher for visitors who had wildlife encounters. Table 4 shows that wildlife encounters may be a more significant factor than pet ownership in mediating tourists’ immediate experiences of Panda Base.

Table 4.

t-test on visitation experiences evaluation based on wildlife encounter (WE/NE).

4.3. Pairwise Analysis Based on Pet Ownership and Wildlife Encounter

The interconnectedness of pet ownership and wildlife encounters means that the two variables do not produce exclusive tourist groups. On the contrary, POs can also be either WEs or NEs. Such means that a pairwise analysis is needed to probe the interconnectedness between pet ownership and wildlife encounters. The normality test is needed to determine whether a parametric analysis, such as ANOVA, is possible. Data transformation or non-parametric analysis are the alternatives if the data are not normally distributed.

The results of Table 5 show that the data in the evaluated experiential dimensions of Panda Base were not normally distributed. Log, square root, and box–cox transformations demonstrated that none of these achieved a Shapiro–Wilk p-value greater than 0.05, indicating the data’s departure from normality in spite of the data transformation. Hence, to minimize statistical errors, Mann–Whitney U tests were conducted to investigate how pet ownership and wildlife encounters may impact visitors’ experiences at Panda Base.

Table 5.

Normality test on evaluations of the visitation experiences of participants.

Table 6 shows that wildlife encounters and pet ownership can mutually influence visiting experiences such as the enjoyment of nature (p = 0.003), feeling of calmness (p = 0.017), and participation in conservation volunteering (p = 0.021). It shows that pet owners who did not encounter wildlife enjoyed nature less significantly than other tourists. Pet owners who experienced wildlife encounters reported significantly more calmness than non-owners without such encounters (p = 0.037). However, the difference was not pronounced between owners and non-owners with wildlife encounters (p = 0.383). Pet owners who experienced wildlife encounters were significantly more likely to participate in conservation volunteer programs than other tourists. Table 6 illustrates the highly complex and intertwined relationship between pet ownership and wildlife encounters during visiting experiences at Panda Base.

Table 6.

Kruskal–Wallis and post hoc tests on pet ownership and wildlife encounters.

4.4. Different Pets and Their Influence on the Visiting Experience

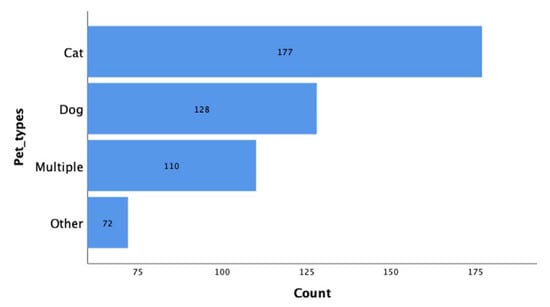

In total, 487 visitors reported being pet owners. Cats (36.34%) were the most popular pets among POs, followed by dog owners (26.28%). More people had multiple pets (22.59%) than other pets (14.78%), such as birds, goldfish, reptiles, and hamsters (Figure 1). Table 7 shows whether owning different types of pets could produce distinctive visitor experiences for pet owners. It shows no significant difference between pet owners (p > 0.05). However, we observed that owners of other pets were most likely to enjoy all aspects of visiting Panda Base, followed by dog owners. In contrast, cat owners consistently rated their visiting experiences as worse than those of other pet owners.

Figure 1.

Types of pet claimed by participants.

Table 7.

Kruskal–Wallis tests on POs with different types of pets.

Table 8 shows that pet owners experienced wildlife encounters in different ways (p = 0.001). Owners of other pets (61.1%) were more likely to observe wildlife encounters at Panda Base, whereas dog owners (39.8%) were the least sensitive to wildlife.

Table 8.

Wildlife encounter frequency and pet types.

5. Discussion

As the first study to explore the entanglements of wildlife, pets, and humans in animal care organizations, this paper employs an ecological-phenomenological lens to understand the interconnected and complex relationships between visitors and non-human beings in tourism, using Panda Base as a venue. While previous research on nature-based tourism has highlighted the potential influence of pets on wildlife tourism experiences—particularly through their impact on ecological systems and their emerging role as active stakeholders [2,3,6]—the specific relationship between pet ownership and wildlife tourism remains underexplored. This study addresses this gap by offering an initial investigation into how pet–human dynamics shape wildlife encounters and tourism practices.

Affordance and constraint are two key concepts that the ecological-phenomenological perspective employs to understand animal interactions with their environment. Specifically, affordances contribute to how individuals experience and interact with their surroundings in a subjective, direct, and meaningful way. The most straightforward influence of affordance in this study is that visitors with pets were much more likely to observe and interact with wildlife. According to Dashper and Brymer [7], affordance focuses on what is offered to individuals rather than mere physical descriptions. Pet owners’ previous experiences with pet animals shape their ability to perceive and interact with wildlife, manifesting in their tendency to observe and interact with wildlife at Panda Base actively. Rather than seeing wildlife as a mere physical presence at Panda Base, pet owners were more attuned to the unstructured and random presence of wildlife. It also means that pet owners’ intimacy with pets enhances their ability to perceive and appreciate wildlife’s behaviors and presence more closely.

The pet owner’s higher rate of engagement with wildlife at Panda Base also means they were agents mobilized to interact with the environment in a dynamic fashion with other agents [7] (p. 6). Pet owners approached their tourism activities in the natural environment at Panda Base with a varied understanding of the functional opportunities the environment affords, which led to their sensitivity to the presence of wildlife and greater appreciation of interactions with wildlife. For example, pet owners without wildlife encounters enjoyed the nature of Panda Base the least (Table 6), indicating that pet owners’ functional approach and goal-directed behaviors [7] influenced their participation in tourism activities and the natural environment.

Pet ownership is also an embodied experience that affords a difference in visitors’ ability to perceive and respond to the wildlife they encounter, emphasizing a mutual influence between visitors, pets, and wildlife. For example, Table 6 shows that wildlife encounters generate significant differences in pet owners’ feeling of calmness at the Panda Base, while this impact was not observed among non-owners. Wildlife encounters generated the highest level of calmness among pet owners, while the lack of wildlife encounters caused the greatest anxiety among this group. This embodied experience of the Panda Base environment, influenced by the presence or absence of wildlife, means that pet owners, in general, tend to have richer wildlife observation experience and greater engagement than non-owners. Additionally, this sensitivity to wildlife encounters in pet owners’ feelings of calmness can pose a significant constraint to pet owners’ experience of the Panda Base. As pet owners naturally seek “stable and effective patterns of behavior” [7] (p. 5), such as encountering wildlife during their visit to Panda Base, the lack of wildlife encounters presented significant constraints in pet owners’ enjoyment of this venue.

When combined, pet ownership and wildlife encounters can lead to a significant difference in visitors’ interest in volunteering for wildlife conservation programs (see Table 6). It means pet ownership and wildlife encounters were necessary affordances, allowing visitors to become attuned to volunteering opportunities. From an ecological-phenomenological perspective, individuals engage in goal-directed activities [7]. The volunteer program is one of the tourism activities at Panda Base, oriented toward specific goals. At the same time, this study reveals that pet owners’ experiences with wildlife also increase their awareness of wildlife and animal conservation, making them more likely to recognize the importance of volunteer roles. In contrast, visitors without pets and those who had wildlife encounters experienced significant constraints in their perception of volunteer opportunities, which may have led to their lack of interest in participating in the volunteer programs.

Tuan’s (2017) [11] approach to human dominance and affection in contemporary pet ownership suggests that human affection towards pets evolved from their control and power over animals. Multispecies tourism offers activities and spaces that facilitate the transformation of human dominance into affectionate bonds with non-human beings. This suggests that multispecies tourism also provides opportunities to explore and enact alternative power dynamics. A comparison between Table 3 and Table 4 validates this observation. Table 3 shows that pet ownership only generated a significant difference in the enjoyment of nature in POs and NOs, whereas, in Table 4, whether visitors had wildlife encounters or not created significant deviances in terms of the visitors’ enjoyment of nature, feeling of calmness, willingness to donate, and willingness to volunteer. The wildlife encounter played a more dynamic and robust role in mediating the affordances and constraints of the Panda Base environment.

A closer look at Table 4 reveals that wildlife encounters, as a random yet dynamic factor, did not significantly alter visitors’ perceptions of Panda Base (e.g., biodiversity and natural environment). Rather, the wildlife encounter could produce significant changes in more subjective and, hence, anthropocentric experiences of the visitors (e.g., their feelings, pleasure, and willingness). This suggests that the presence of wildlife did not benefit visitors’ more objective evaluation of Panda Base but was specifically oriented towards visitors’ well-being and experience. Tuan [11] believed that affection towards pets is a form of human dominance’s anodyne. In parallel, our study shows that visitors’ interest in wildlife encounters also entails a form of dominance through human centrality. This anthropocentric experience at Panda Base introduces an implicit sociological factor into the environmental constraints [7], as visitors may have adopted an affectionate yet dominant stance when encountering wildlife. Although this connection with wildlife was shared as an enjoyable, pleasant, and willing experience for the visitors, it maintains human dominance by affording exclusive benefits to human beings.

The result of the survey supports the ecological-phenomenological perspective that wildlife, pets, and human participants experience entangled relationships in multispecies tourism venues. Table 7 and Table 8 further show that this interaction can be rather dynamic and complex depending on the types of pets owners and non-owners have. There are also nuanced differences caused by whether people had pet ownership or wildlife encounters. While pet ownership and wildlife encounters triggered different environmental affordances and constraints in the multispecies tourism experiences, this study also demonstrates the persistent influence of anthropocentrism in people’s tourism experiences. We concur with Tuan’s point that affection and domination provide the specific framework with which people interact with non-human beings. While pets experience family affinity and affection from their human owners, tourists’ affection towards wildlife is expressed through their enjoyment of the visitation experience and interest in wildlife conservation programs.

6. Conclusions

This paper studied the interactions between pets, wildlife, and human visitors in a multispecies tourism setting. The ecological-phenomenological perspective was employed to understand how these interactions become deeply rooted in the interplay between individuals and these settings. Key concepts such as affordance (the environment’s offering of meaningful interaction) and constraint (limitations imposed by the environment) explain the link between pet ownership and wildlife encounters at the Panda Base. This study contributes to the understanding of pet-wildlife relationships in the context of wildlife tourism. It shows that pets are a significant advantage, providing owners with richer and more frequent wildlife encounters. Although pets are not allowed at the Panda Base, owners’ interactions with pets continue to influence their interests in wildlife encounters and observations. The key insight is that multispecies interactions in tourism activities can be complex and dynamic, and different types of pets, pet ownership, and wildlife encounters could all influence visitors’ experiences in nuanced ways.

This study shows that anthropocentrism remains the inevitable constraint that structures and orients multispecies tourism experiences despite non-human animals being active participants in these activities. Dominance and control over non-human animals thus become the norm in a setting where animals, although free to roam, are still relatively confined within a formal built environment. We characterize this as a form of “affectionate domination” over wildlife: spaces where people’s anthropocentric dominance partakes in a seemingly benevolent and affectionate transformation yet still manifests a human–animal dichotomy.

This paper provides several empirical implications for practitioners and managers in animal care facilities. First, the study’s results demonstrate that wildlife encounters can create a significant gap in visitors’ experiences, as they encourage visitors to appreciate wildlife better and acknowledge its presence. For an animal care organization like the Panda Base, the giant panda is often seen as the organization’s most ubiquitous attraction, whereas visitors’ encounters with other wildlife, whether captive or free roaming, are largely overlooked. This study demonstrates that Panda Base can enhance visitors’ satisfaction and foster their willingness to learn about animals by incorporating and introducing animals other than giant pandas. For example, education programs on birds, insects, or other small mammals can effectively build human–animal connections. Hence, animal care organizations can benefit from recognizing visitors’ pet ownership when introducing conservation messages and programs.

For academics, this interconnection between pet ownership and wildlife encounters warrants further investigation as a key human–animal connection where domination and affection intersect. The ecological-phenomenological perspective offers a lens to probe this persistent anthropocentric power interplay and can, therefore, play a crucial role in creating a more inclusive society for all species. We argue that zoological venues would be a suitable place to initiate these changes, as they already house multiple species.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.G.; methodology, Y.G.; software, Y.G.; validation, Y.G.; formal analysis, Y.G.; investigation, Y.G.; resources, Y.G.; data curation, Y.G.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.G.; writing—review and editing, Y.G. and D.F.; visualization, Y.G.; supervision, D.F.; project administration, Y.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study in accordance with the “Measures for Ethical Review of Life Sciences and Medical Research Involving Human Subjects” (关于印发涉及人的生命科学和医学研究伦理审查办法的通知) issued by the Chinese Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Science and Technology. See: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2023-02/28/content_5743658.htm (accessed on 24 October 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to ongoing use of the dataset for additional research and publications.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to our “Fluff Committee”—Mocha, Louie, Silver, Jazz, and Lolo—for inspiring this study through their presence, companionship, and everyday multispecies wisdom.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Fennell, D. Tourism and Animal Ethics, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Valjarević, A.; Vukoičić, D.; Valjarević, D. Evaluation of the tourist potential and natural attractivity of the Lukovska Spa. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2017, 22, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donici, D.S.; Dumitras, D.E. Nature-based tourism in national and natural parks in Europe: A systematic review. Forests 2024, 15, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovardas, T.; Poirazidis, K. Environmental policy beliefs of stakeholders in protected area management. Environ. Manag. 2007, 39, 515–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, N.; Iosifides, T.; Evangelinos, K.I.; Florokapi, I.; Dimitrakopoulos, P.G. Investigating knowledge and perceptions of citizens of the National Park of Eastern Macedonia and Thrace, Greece. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2012, 19, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welling, J.; Ólafsdóttir, R.; Árnason, Þ.; Guðmundsson, S. Participatory planning under scenarios of glacier retreat and tourism growth in southeast Iceland. Mt. Res. Dev. 2019, 39, D1–D13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dashper, K.; Brymer, E. An ecological-phenomenological perspective on multispecies leisure and the horse-human relationship in events. Leis. Stud. 2019, 38, 394–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, T. Humankind: Solidarity with Non-Human People; Verso Books: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lobo, L.; Heras-Escribano, M.; Travieso, D. The history and philosophy of ecological psychology. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Read, C.; Szokolszky, A. Ecological psychology and enactivism: Perceptually-guided action vs. sensation-based enaction. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan, Y.-F. Dominance and Affection; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Haraway, D.J. When Species Meet; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2013; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Despret, V. The becomings of subjectivity in animal worlds. Subjectivity 2008, 23, 123–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crutzen, P.J. The “anthropocene”. In Earth System Science in the Anthropocene; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; pp. 13–18. [Google Scholar]

- Stebbins, R.A. Leisure as not work: A (far too) common definition in theory and research on free-time activities. World Leis. J. 2018, 60, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veal, A.J. Joffre Dumazedier and the definition of leisure. Loisir Société Soc. Leis. 2019, 42, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danby, P.; Dashper, K.; Finkel, R. Multispecies leisure: Human-animal interactions in leisure landscapes. Leis. Stud. 2019, 38, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo-Fernández, A.; Moral-Cuadra, S.; Menor-Campos, A.; Lopez-Guzman, T. Pet tourism: Motivations and assessment in the destinations. Consum. Behav. Tour. Hosp. 2023, 18, 335–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Leung, X.Y.; Xu, H. Examine pet travel experiences from human–pet interaction: The moderating role of pet attachment. Tour. Rev. 2024, 79, 812–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, W.; Kim, S.; Baah, N.G.; Jung, H.; Han, H. Role of physical environment and green natural environment of pet-accompanying tourism sites in generating pet owners’ life satisfaction. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2023, 40, 399–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, H.M.; Sousa, B.; Carvalho, A.; Santos, V.; Lopes Dias, Á.; Valeri, M. Encouraging brand attachment on consumer behaviour: Pet-friendly tourism segment. J. Tour. Herit. Serv. Mark. 2022, 8, 16–24. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H.-C.; Chang, Y.-Y. Pet attachment, experiential satisfaction and experiential loyalty in medical tourism for pets. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2023, 48, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.; Jo, Y.; Joo, Y.; Jo, H.; Yoon, Y.-S. The impact of pet attachment, perceived value, and travel motivation on loyalty and intention to support in pet tourism: A multi-method approach. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2025, 30, 735–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomassini, L. Can I bring my pet? The space for companion animals in hospitality and tourism. Res. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 12, 99–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mlakar, N.; Korže, S.Z. New tourism trend: Travelling with pets or pet sitting at a pet hotel. Contemp. Issues Tour 2022, 221, 229–242. [Google Scholar]

- Quan, W.; Kim, S.; Baah, N.G.; Kim, H.; Han, H. Perceptions of pet-accompanying tourism: Pet owners vs. nonpet owners. J. Vacat. Mark. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyhus, P.J. Human–wildlife conflict and coexistence. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2016, 41, 143–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pooley, S.; Bhatia, S.; Vasava, A. Rethinking the study of human–wildlife coexistence. Conserv. Biol. 2021, 35, 784–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shephard, S.; von Essen, E.; Gieser, T.; List, C.J.; Arlinghaus, R. Recreational killing of wild animals can foster environmental stewardship. Nat. Sustain. 2024, 7, 956–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waller, D.M.; Reo, N.J. First stewards: Ecological outcomes of forest and wildlife stewardship by indigenous peoples of Wisconsin, USA. Ecol. Soc. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willmott, N.J.; Wong, B.B.; Lowe, E.C.; McNamara, K.B.; Jones, T.M. Wildlife exploitation of anthropogenic change: Interactions and consequences. Q. Rev. Biol. 2022, 97, 15–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scanes, C.G. Human activity and habitat loss: Destruction, fragmentation, and degradation. In Animals and Human Society; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 451–482. [Google Scholar]

- Abrahms, B. Human-wildlife conflict under climate change. Science 2021, 373, 484–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahms, B.; Carter, N.H.; Clark-Wolf, T.; Gaynor, K.M.; Johansson, E.; McInturff, A.; Nisi, A.C.; Rafiq, K.; West, L. Climate change as a global amplifier of human–wildlife conflict. Nat. Clim. Change 2023, 13, 224–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, B. Climate change, human–wildlife conflict, and biodiversity loss. In Routledge Handbook of Animal Welfare; Routledge: London, UK, 2022; pp. 311–320. [Google Scholar]

- Mawdsley, J.R.; O’malley, R.; Ojima, D.S. A review of climate-change adaptation strategies for wildlife management and biodiversity conservation. Conserv. Biol. 2009, 23, 1080–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjerke, T.; Østdahl, T.; Kleiven, J. Attitudes and activities related to urban wildlife: Pet owners and non-owners. Anthrozoös 2003, 16, 252–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coose, S.; Thomsen, B.; Dodsworth, T.; Eckl, F.; Thomsen, J.; Such, R.; Guardia-Uribe, S.; Villar, D.A.; Gosler, A. Beyond saving lives: Political ecology, animal welfare, and the challenges of wildlife rehabilitation in Costa Rica. Hum. Anim. Interact. 2025, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuttlewood, C.Z.; Greenwell, P.J.; Montrose, V.T. Pet ownership, attitude toward pets, and support for wildlife management strategies. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 2016, 21, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjerke, T.; Ødegårdstuen, T.S.; Kaltenborn, B.P. Attitudes toward animals among Norwegian children and adolescents: Species preferences. Anthrozoös 1998, 11, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hepper, P.G.; Wells, D.L. Pet ownership and adults’ views on the use of animals. Soc. Anim. 1997, 5, 45–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowd, A.D. Fears and understanding of animals in middle childhood. J. Genet. Psychol. 1984, 145, 143–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driscoll, J.W. Attitudes toward animal use. Anthrozoös 1992, 5, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furnham, A.; Pinder, A. Young people’s attitudes to experimentation on animals. Psychologist 1990, 10, 444–448. [Google Scholar]

- Furnham, A.; Heyes, C. Psychology students’ beliefs about animals and animal experimentation. Personal. Individ. Differ. 1993, 15, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, E.S.; Serpell, J.A. Childhood pet keeping and humane attitudes in young adulthood. Anim. Welf. 1993, 2, 321–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serpell, J. In the Company of Animals: A study of Human-Animal Relationships; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Serpell, J.; Paul, E. Pets and the development of positive attitudes to animals. In Animals and Human Society; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2002; pp. 165–182. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, K. Man and the Natural World: Changing Attitudes in England 1500–1800; Penguin: London, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, A.M.; Meyers, N.M. Health enhancement and companion animal ownership. Annu. Rev. Public Health 1996, 17, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dembicki, D.; Anderson, J. Pet ownership may be a factor in improved health of the elderly. J. Nutr. Elder. 1996, 15, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNicholas, J.; Gilbey, A.; Rennie, A.; Ahmedzai, S.; Dono, J.-A.; Ormerod, E. Pet ownership and human health: A brief review of evidence and issues. BMJ 2005, 331, 1252–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, J.M. Pet ownership and health. In The Psychology of the Human-Animal Bond—A Resource for Clinicians and Researchers; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staats, S.; Wallace, H.; Anderson, T. Reasons for companion animal guardianship (pet ownership) from two populations. Soc. Anim. 2008, 16, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branson, S.; Boss, L.; Cron, S.; Kang, D.-H. Examining differences between homebound older adult pet owners and non-pet owners in depression, systemic inflammation, and executive function. Anthrozoös 2016, 29, 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branson, S.M.; Boss, L.; Cron, S.; Turner, D.C. Depression, loneliness, and pet attachment in homebound older adult cat and dog owners. J. Mind Med. Sci. 2017, 4, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ein, N.; Li, L.; Vickers, K. The effect of pet therapy on the physiological and subjective stress response: A meta-analysis. Stress Health 2018, 34, 477–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hui Gan, G.Z.; Hill, A.-M.; Yeung, P.; Keesing, S.; Netto, J.A. Pet ownership and its influence on mental health in older adults. Aging Ment. Health 2020, 24, 1605–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, J.M. Stressful life events and use of physician services among the elderly: The moderating role of pet ownership. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1990, 58, 1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonacopoulos, N.M.D.; Pychyl, T.A. An examination of the potential role of pet ownership, human social support and pet attachment in the psychological health of individuals living alone. Anthrozoös 2010, 23, 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeuchi, T.; Taniguchi, Y.; Abe, T.; Seino, S.; Shimada, C.; Kitamura, A.; Shinkai, S. Association between experience of pet ownership and psychological health among socially isolated and non-isolated older adults. Animals 2021, 11, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kretzler, B.; König, H.-H.; Hajek, A. Pet ownership, loneliness, and social isolation: A systematic review. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2022, 57, 1935–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, L.; Protopopova, A.; Birkler, R.I.D.; Itin-Shwartz, B.; Sutton, G.A.; Gamliel, A.; Yakobson, B.; Raz, T. Human–dog relationships during the COVID-19 pandemic: Booming dog adoption during social isolation. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2020, 7, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajek, A.; König, H.-H. How do cat owners, dog owners and individuals without pets differ in terms of psychosocial outcomes among individuals in old age without a partner? Aging Ment. Health 2020, 24, 1613–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yabroff, K.R.; Troiano, R.P.; Berrigan, D. Walking the dog: Is pet ownership associated with physical activity in California? J. Phys. Act. Health 2008, 5, 216–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, C.; König, H.-H.; Hajek, A. Differences in self-esteem between cat owners, dog owners, and individuals without pets. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, A.; Towell, T. Cat and dog companionship and well-being: A systematic review. Int. J. Appl. Psychol 2013, 3, 149–155. [Google Scholar]

- Chiew, S.J.; Hemsworth, P.H.; Melfi, V.; Sherwen, S.L.; Burns, A.; Coleman, G.J. Visitor attitudes toward little penguins (Eudyptula minor) at two Australian zoos. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 626185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prokop, P.; Tunnicliffe, S.D. Effects of having pets at home on children’s attitudes toward popular and unpopular animals. Anthrozoös 2010, 23, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daston, L.; Mitman, G. Thinking with Animals: New Perspectives on Anthropomorphism; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Lorimer, J. Wildlife in the Anthropocene: Conservation after Nature; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Brantz, D. Beastly Natures: Animals, Humans, and the Study of History; University of Virginia Press: Charlottesville, VA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- News, P. Lai Yichang Xiongmao Shijie de Citywalk [A City Walk in the World of the Giant Panda]. Available online: https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_27864621 (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Fennell, D.A.; Guo, Y. Ubiquitous Love or Not? Animal Welfare and Animal-Informed Consent in Giant Panda Tourism. Animals 2023, 13, 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y. 13 ”Cute, but get up and work!”: The biophilia hypothesis in tourists’ linguistic interactions with pandas. In Exploring Non-Human Work in Tourism: From Beasts of Burden to Animal Ambassadors; De Gruyter Oldenbourg: Berlin, Germany; Boston, MA, USA, 2021; Volume 5, p. 225. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y.; Fennell, D. Preference for Animals: A Comparison of First-Time and Repeat Visitors. J. Zool. Bot. Gard. 2023, 5, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Fennell, D. What makes the giant panda a celebrity? Celebr. Stud. 2023, 15, 474–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y. The heritage of cute: Commodifying pandas in urban and rural China. In Tourism, Heritage and Commodification of Non-Human Animals: A Post Humanist Reflection; López, Á., Quintero, J., Kline, C., Eds.; CABI: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- de Winter, J.F.; Dodou, D. Five-point likert items: T test versus Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon (Addendum added October 2012). Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 2010, 15, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).