Simple Summary

For many Arctic Native communities, nothing from the natural world is wasted. This study looks at how Alaska Native and Greenlandic Inuit women have used parts of fish, such as skins, bones, and internal organs, to craft everyday life items like clothing, containers, tools, glue, and jewellery. These objects served practical purposes and linked Natives to their ancestors, fish and the sea. Even as glass beads were introduced through trade during early colonial contact, traditional practices endured, adapting to new materials. By documenting these lesser-known uses of fish remnants, the research shows how Indigenous knowledge supports a way of living that is respectful, sustainable, and innovative. These traditions can help us think differently about how we use natural resources today, especially in areas like sustainable fashion. Understanding and valuing these practices offers important lessons for living in balance with the environment today.

Abstract

This paper investigates the cultural, spiritual, and ecological use and value of fish by-products in the material practices of Alaska Native (Indigenous Peoples are the descendants of the populations who inhabited a geographical region at the time of colonisation and who retain some or all of their own social, economic, cultural, and political institutions. In this paper, I use the terms “Indigenous” and “Native” interchangeably. In some countries, one of these terms may be favoured over the other.) and Greenlandic Inuit women. It aims to uncover how fish remnants—skins, bones, bladders, vertebrae, and otoliths—were transformed through tanning, dyeing, and sewing into garments, containers, tools, oils, glues, and adornments, reflecting sustainable systems of knowledge production rooted in Arctic Indigenous lifeways. Drawing on interdisciplinary methods combining Indigenist research, ethnographic records, and sustainability studies, the research contextualises these practices within broader environmental, spiritual, and social frameworks. The findings demonstrate that fish-based technologies were not merely utilitarian but also carried symbolic meanings, linking wearers to ancestral spirits, animal kin, and the marine environment. These traditions persisted even after European contact and the introduction of glass trade beads, reflecting continuity and cultural adaptability. The paper contributes to academic discourse on Indigenous innovation and environmental humanities by offering a culturally grounded model of zero-waste practice and reciprocal ecology. It argues that such ancestral technologies are directly relevant to contemporary sustainability debates in fashion and material design. By documenting these underexamined histories, the study provides valuable insight into Indigenous resilience and offers a critical framework for integrating Indigenous knowledge systems into current sustainability practices.

1. Introduction

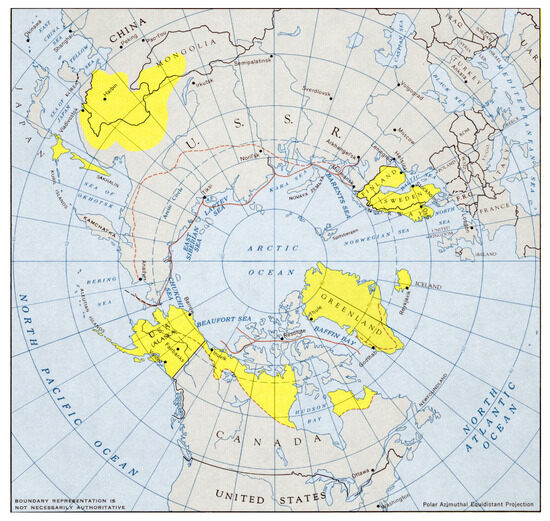

The Arctic is home to approximately four million people, including 400,000 Indigenous Peoples with ancestral ties to the region. These communities belong to forty ethnic groups that, despite their differences, share cultural traits and have engaged in trade and shared lifeways across the Circumpolar North for millennia. Their languages and cultures are both diverse and interconnected, forming a network that transcends the political boundaries imposed by modern nation-states [1]. While this paper focuses on Indigenous communities in Alaska—specifically the Inuit, Yup’ik, Sugpiaq, Iñupiaq, and Athabascan—as well as the Greenlandic Inuit descended from the historical migration and settlement of Alaska Inuit across areas of the Canadian Arctic and Greenland, it also considers other Arctic and Subarctic Indigenous groups with documented traditions of fish skin and fish by-product use. These include the Ulchi, Nivkh, and Nanai of Siberia; the Ainu from Hokkaido Island in Japan and Sakhalin Island in Russia; the Hezhe from northeast China; the Saami of northern Scandinavia; and non-Indigenous Icelanders (Figure 1). These groups, though geographically dispersed, share a history of subsistence-based economies, highly specialised technologies for harvesting and processing fish skins, a thorough ecological knowledge, and spiritual relationships with their environment [2].

Figure 1.

Map of the Arctic and Sub-Arctic regions indicating areas of historical fish skin and fish remnant use. Library of Congress, Washington, DC, USA.

The enquire situates fish not only as a food source but also as a culturally precious material. Indigenous Arctic communities developed techniques to turn fish skin and by-products into clothing, tools, and ritual objects essential for survival and for defining identity and sacredness. Without these technologies, sustained human presence in the Arctic would have been impossible. Animal skins, including fish, were transformed into tailored garments that provided the necessary insulation [3]. Their use in garments and artefacts illustrates the interdependence between human communities and aquatic environments [4].

This paper therefore traces the historical and cultural uses of fish skin technologies, not only to document overlooked material practices but also to argue for their relevance in contemporary sustainability discourse. By drawing attention to these practices, the article contributes to ongoing conversations about zero-waste ethics and Indigenous-led sustainability. As global industries increasingly seek ways to reduce waste and maximise resource use, principles rooted in Indigenous fish skin traditions offer alternative frameworks. An understanding of fish as both a livelihood and a material resource highlights the Indigenous knowledge that is urgently needed in sustainable design. This work aims to bridge historical and contemporary practice to recognise the implications of these Arctic traditions for academic research and the future of the environment.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Indigenist Research Methodology

This contribution employs an Indigenist research methodology to examine the use of fish remnants—skins, bones, heads, bladders, vertebrae, and otoliths—in garments, tools, organic tanning agents, binders, and adornments across Alaska and Greenland. Documenting these materials remains challenging due to historical gaps, colonial disruptions, and the erosion of traditional knowledge. Responding to these challenges, this methodology prioritises Indigenous worldviews, including the spiritual dimensions of these practices [5,6].

As a Research Associate at the Smithsonian Arctic Studies Center, I have spent the past decade collaborating with Elders and knowledge holders such as June Pardue (Sugpiaq/Iñupiaq) [7], Anatoly Donkan (Nanai) [8], Wengfen Yu (Hezhe) [9,10], Lotta Rhame (Swedish) [11], and Shigehiro Takano (Japanese engaged with the Ainu community). This collaborative framework respects Indigenous cultural protocols, enabling Indigenous and Western methods to complement one another. Knowledge was co-produced through long-term engagements, including museum visits, interviews, workshops, and practical experimentation with fish skin tanning and making. This methodology not only facilitated the retrieval of endangered practices but also highlighted Indigenous practices, avoiding extractive approaches. Together, we triangulated museum artefact analysis with oral histories and lived experience, conducting object-based research in museums across Alaska, Iceland, Sweden, Italy, Hokkaido, and Germany.

2.2. Ethnographic Research

Ethnographic documentation of Alaska Native lifestyles has a long tradition, dating back to Nelson [12], Osgood [13], Sheldon Jackson, and, later on, Frederica de Laguna [14], Hatt and Taylor [15], and Fitzhugh and Kaplan [16]. Inuit clothing has attracted outstanding scholarly attention in recent decades, with studies on Arctic dress and footwear emerging from European, Asian, American, and Inuit researchers. In this paper, these studies were complemented by focused analyses on fish skin and fish remnant materials by Hickman [17], VanStone [18], Oakes and Riewe [19], Buijs [20], Reed [21], and Vávra [22]. More detailed treatment of ritual dimensions has been addressed by Chaussonet [23,24], Driscoll [3], and Buijs and Petersen [25]. Building on this legacy, my research incorporated both archival and practice-based data, gathered through artefact studies in over 40 museums across three continents. These visits were conducted, whenever possible, with Indigenous and non-Indigenous fish skin artists and Elders to access insights and validate object provenance. Items spanning from c. 1830 to 1990 were photographed, catalogued, and examined for material composition, technique, wear patterns, and spiritual content.

In 2019, I extensively researched Alaska Native collections at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History and the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, DC, USA. In Alaska, I examined collections alongside Sugpiaq artist June Pardue at the Anchorage Museum, and later at the Wells Fargo Museum (Anchorage), the Alaska State Museum (Juneau), the Sheldon Jackson Museum (Sitka), the Carrie M. McLain Memorial Museum (Nome), the Pratt Museum (Homer), the Alutiiq Museum (Kodiak Island), and the University of Alaska Museum of the North (Fairbanks).

My investigation of Amur River fish skin collections began in 2018 at the Musée du Quai Branly–Jacques Chirac in Paris with Lotta Rahme. That same year, I visited the Blönduós Textile Museum in Iceland and the Hezhe Ethnic Minority Culture Museum and Jiejinkou Hezhe Village Ethnic Museum in Heilongjiang, China, accompanied by Hezhe artist Wenfen Yu [9,10]. In 2019, I examined related Amur River collections at the V&A, London, and in 2021 at the Museo di Antropologia ed Etnologia in Florence. In 2022, I studied Amur River fish skin artefacts at the Minneapolis Institute of Art with conservator Courtney VonStein Murray. In 2023, I conducted research with Nanai artist Anatoly Donkan at the Ethnological Museum in Berlin and visited the Museum of Ethnography in Budapest to examine their fish skin holdings. Together with Lotta Rahme, we studied relevant Amur River materials at the Museum of Ethnography in Stockholm.

At the Penn Museum, I have carried out extensive research on both Alaska Native and Amur River collections and co-developed an online course on fish skin traditions in collaboration with June Pardue. This collaboration continues through the co-authorship of the chapter Aquatic Skins for the forthcoming Conservation of Leather and Related Materials volume (Routledge), co-written with conservators Sophie Rowe-Kancleris (Museum of Cultural History, Oslo), VonStein Murray, and Elder collaborators June Pardue, Anatoly Donkan, and Lotta Rahme.

Further fieldwork in 2021 took place across Hokkaido with June Pardue and Anatoly Donkan, culminating in a conference at the Bunka Gakuen Costume Museum [8]. We visited the Upopoy National Ainu Museum and Park, the Hokkaido University Museum, the Nibutani Ainu Culture Museum, and the Shigeru Kayano Ainu Museum. These visits represent the basis of a comparative museological material analysis rooted in collaborative engagement with Native experts and museum professionals.

The study extended beyond academic inquiry to include practise-based learning. I co-organised and participated in fish skin tanning workshops carried out with Native Elders to go beyond observational ethnography to relational learning. This phase allowed me not only to document knowledge but also to experience its transmission firsthand, bridging theory and practice. In this way, the research highlights that Indigenous sustainability is not solely about resource use but also a form of knowing, healing, and remembering.

In 2020, I co-developed the digital Sugpiaq Fish Skin Tanning Workshop with Sugpiaq Elder June Pardue [7]. In 2019, supported by the Fulbright Commission, I co-organised the Athabaskan Fish Skin Workshop with Denina Athabascan artist Joel Isaak at Parsons School of Fashion, New York, and led a Fashion Sketchbook Workshop at the Anchorage Museum’s Smithsonian Arctic Studies Center with local Alaska Native artists, co-funded by the CIRI Foundation. In 2018, I co-created a Hezhe Fish Skin Workshop with Hezhe artist Wenfen Yu at the Hezhe Ethnic Minority Culture Museum in Heilongjiang, China, engaging students from the University of the Arts London [9,10], and facilitated an Ainu Fish Skin Workshop with Shigehiro Takano at the Nibutani Ainu Culture Museum, Hokkaido, with students from Japanese fashion universities. These were supported by FRPAC, the Japan Foundation Endowment Committee, and the Sasakawa Foundation. That same year, I co-created a Nordic Fish Skin Workshop led by Swedish Elder Lotta Rahme at the Icelandic Textile Centre, Blönduós, with students from Nordic universities, funded by the Nordic Culture Fund and the Society of Dyers and Colourists.

These workshops have been central to my methodological approach, offering a framework for collaborative research and knowledge exchange.

2.3. Regenerative Systems Research

This research employs a Regenerative Systems Research approach to examine sustainable design practices rooted in Indigenous fish skin and fish by-product traditions. Informed by over 25 years in luxury fashion and a decade leading the BA Fashion Print programme at Central Saint Martins, University of the Arts London, my practice-led inquiry prioritises ecological responsibility [26].

Fish by-products offer models for regenerative systems that emphasise local materials, low-impact processes, and collective knowledge. These systems challenge extractive production modes, enhance biodiversity, and contribute to fair economies. Reviving such practices strengthens cultural heritage while enabling innovation. Positioned within regenerative fashion, these practices exemplify a shift towards design that aligns environmental sustainability with social equity across the entire fashion lifecycle. Social justice in this context refers to the equitable distribution of resources, opportunities, and environmental benefits, particularly for communities historically marginalised by extractive fashion systems. It involves rethinking how raw materials are sourced, how labour is valued, and how waste is managed, ensuring that human and non-human well-being are prioritised throughout. Regenerative approaches seek not only to repair ecological damage but also to revitalise local economies, cultural practices, and intergenerational knowledge systems. This includes supporting community-led initiatives and Indigenous technologies such as fish skin processing [27].

3. The Arctic’s Extraordinary Abundance

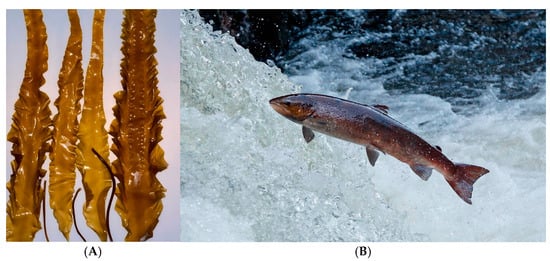

Often mischaracterised as barren, the Arctic is in fact marked by alternating periods of scarcity and abundance. Continuous summer daylight fosters the growth of berries, grasses, mushrooms, and sea algae (Figure 2A), and supports rich ecosystems that attract salmon and other species (Figure 2B) [28]. Indigenous Arctic communities have long relied on this cyclical abundance to sustain themselves through harsh winters. In regions unsuitable for agriculture, livelihoods depended on herding, hunting, and fishing—activities aligned with animal’s seasonal migrations. Seasonal rhythms dictated fishing activities, requiring travel over land or sea ice to access productive fishing sites. Although men and women both participated in fishing, women were primarily responsible for preserving food and repurposing fish remains [2].

Figure 2.

(A) Alaska sugar kelp (Saccharina latissima). (B) Salmon, Alaska.

Beyond nourishment, fish provided skins, bones, heads, bladders, and oils—materials used since ancient times [2]. Once the flesh was consumed, women transformed the remains into garments, tools, and containers. This practice reflects an ethos of full utilisation and environmental respect, where nothing was wasted. In isolated communities without external supply chains, families relied entirely on local resources. The specialised tasks of processing animal skins and making clothing have traditionally been entrusted to women in Inuit communities. These skills were not only practical but also socially highly valued and could determine a woman’s position within her community. Sewing skill was a treasured attribute that could enhance family prospects. Despite today’s availability of mass-produced clothing, sewing remains an important expression of cultural identity and intergenerational knowledge. Skin garments continue to have artistic, historical, and spiritual value, and maintain the continuity of women’s expertise in material traditions [25]. Today, while many Arctic communities engage with tourism and commercial fishing, traditional subsistence practices persist. Fish have been central to Arctic diets and lifeways since the Palaeolithic, particularly among coastal cultures whose survival depended on fish availability [22]. These communities have sustained riverine environments through practices grounded in respect for biodiversity and ecological balance, rather than exploiting natural systems.

4. Fish Beyond Food

Fish are among the planet’s most biodiverse vertebrates, vital to ecosystems and economies. While their nutritional roles are well documented, the broader cultural and spiritual relationships between humans and fish within Indigenous Arctic societies are often overlooked. In these contexts, fish not only served as nourishment but was also present in rituals, artefacts, and oral traditions [2].

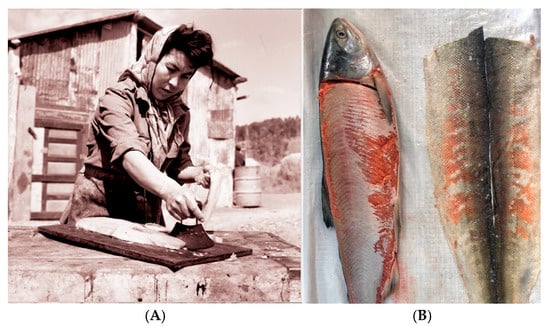

Among Alaska Native and Greenlandic Inuit communities, garments were imbued with spiritual meaning. Sewing was more than a domestic activity; it was a highly respected form of women’s knowledge referred to as “women’s magic” [25], a term introduced by Valérie Chaussonet [23,24] to characterise the spiritual agency in women’s sewing practices across Siberia and Northwestern North America. It captures the spiritual dimensions of clothing production, in which garments symbolise spiritual transformation and maintain harmony with the animal world. Women engaged with animal and elemental spirits during the process of crafting garments. When working with salmon, Alaska Native women (Figure 3A) would connect with the spirit of the water and the fish itself (Figure 3B), which in turn would offer protection to the wearer. Garments became not only functional but also spiritually charged artefacts. Nowadays, the origin of most materials we wear is synthetic and, therefore, less spiritually charged than fish skin, although it is the essence of the wearer to imbue any garment with the spirituality desired [2].

Figure 3.

(A) Katrina processing a king salmon, 1964. Yukon River Alaska collection of the Atwood Resource Center, Anchorage Museum, Alaska. Photographer: Steve McCutcheon. (B) Salmon skin processing. Photo: Elisa Palomino.

Materials such as fish skins, vertebras, bones, and otoliths carried spiritual meanings. Beads were believed to act as portals for spirits, while the quality of a garment reflected the spiritual relationship between the woman and the natural world [25]. Beautifully and carefully made garments were essential to maintaining harmony with animal spirits and were worn during rituals and solstice celebrations [19]. In Alaska and East Greenland, festive clothing remains linked to ritual life, expressing the role of women in safeguarding cultural continuity. The transformation of fish remains into garments and amulets was both a technical and a spiritual labour shaped by generations of inherited knowledge.

5. Alaska Native Lifeways and Aquatic Environments

Wild salmon plays a defining role in shaping the rivers, communities, and cultures of Alaska Natives. Salmon connect rivers to oceans through their remarkable lifecycle. However, salmon habitats have been disrupted by anthropogenic pressures associated with Western industrial activities, including pollution, dam construction, and the warming of waters. Once-abundant wild salmon runs have declined, placing strain on communities that rely on them [29]. Industrial fisheries, policy decisions by non-Natives, and aquaculture practices have further altered salmon ecosystems. Traditional fishing practices grounded in sustainability have been displaced by over-extractive methods. As Fienup-Riordan [30] points out, the problem lies not in the scarcity of resources but in the restriction of access. Whereas in the past Native families could set fish traps near their homes, today they must use motorboats and buy fuel, making traditional fishing unaffordable in times of economic hardship.

While industrial societies continue to drive resource depletion, Indigenous communities, who have long practised sustainable lifeways, are now experiencing the most severe impacts caused by unsustainable practices in other parts of the world [31]. This paper highlights the importance of recognising Indigenous ecological knowledge and rights in sustainability dialogues. Alaska Native relationships with aquatic environments exemplify care and reciprocity models vital to reframing resource management.

6. The Impact of Russians and Later Americans on Alaska Native Environments

Archaeological evidence indicates that the Sugpiaq Native People of Kodiak Island in Southwest Alaska harvested salmon throughout the prehistoric era, with activity increasing over time. Around 900 years ago, they established large villages near major salmon streams to take advantage of abundant fish resources [32].

Before Russian contact, the Sugpiaq People maintained rich cultural traditions that were closely tied to the land, water, and seasonal cycles. Russian explorers and fur traders arriving in the 18th century disrupted these systems, exploiting Native labour for their expertise in seal hunting. This trade eventually led to the depletion of fur skin resources. In response, Alaska’s coastal communities, particularly in Southwest Alaska, where fish skin use was long established, turned increasingly to fish and bird skins for garment-making. These materials, especially salmon skin [7], remained accessible, as they were considered of little commercial value by Russian traders [32].

Simultaneously, Russian education policies aimed to suppress Indigenous knowledge, targeting skills such as navigating Arctic seas, hunting, fishing, and skin garment repair while in the wilderness [7]. Following the U.S. acquisition of Alaska in 1867, the exploitation of resources intensified. The Karluk River, once a thriving salmon stream, was overfished to support a growing industrial economy. The establishment of canneries from 1882 further degraded Native access to traditional foods [33].

Colonial narratives cast Alaska as remote and wild, obscuring long histories of land management. The ecological disruptions introduced by foreign powers continue to shape the region, revealing the long-term costs of settler–colonial extractivism.

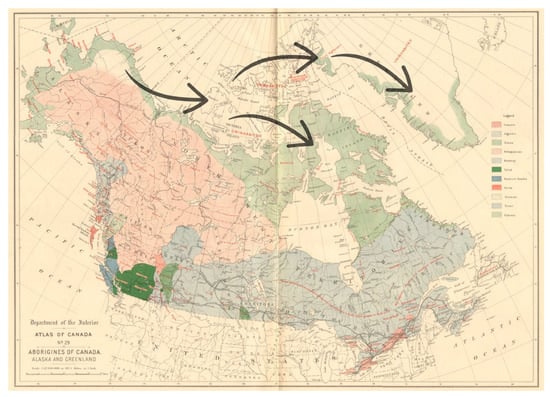

7. The Thule Inuit Migration to Greenland

The migration of the Thule Inuit from northern Alaska into Arctic Canada and Greenland represents one of the most expansive movements in Arctic prehistory. These migrants were descendants of a second wave of migration, displacing the earlier Palaeo-Inuit, who left no known genetic legacy. The Thule brought with them technologies vital to Arctic survival, including sophisticated skin clothing systems [34].

By the fifteenth century, Thule populations had spread across more than 2.8 million km2, from Alaska to Greenland (Figure 4). This expansion required reliable access to food for nourishment and skins for garment production. Greenlandic Inuit, descendants of Thule migrants, maintained semi-nomadic lifeways combining summer salmon fishing with winter seal hunting. These subsistence strategies relied on material knowledge and technical expertise. Ethnographic evidence from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries provides insights of these adaptations [35].

Figure 4.

Map showing the migration routes of the early Thule culture, beginning around 800 years ago (ca. 1200 CE), from the northern Bering Strait region in northwest Alaska into Arctic Canada and Greenland. They initially settled in northwest Greenland. Some later migrated eastward to northeastern Greenland, following the northern coast. Others moved southward along Greenland’s west coast. Library of Congress, Washington, DC, USA.

Women played a critical role in this system by transforming animal skins into clothing essential for survival in extreme climates. Using inherited tools and techniques, they crafted garments from fur, bird skin, and gut—primarily from seals [36]. Archaeological records from Thule-era sites attest to the resourceful use of both durable materials—bones, teeth, antlers, baleen—and more perishable organic elements such as the oesophagus, intestines, and bladders [37]. These assemblages reinforce the ingenuity of Indigenous Arctic material traditions across centuries.

8. Interactions Between Natives and Nature: Clothing Made from Subsistence Fishing

Alaska Native and Greenlandic Inuit traditions emphasise respect for the animals that sustain human life, such as fish, as well as sea mammals such as seals and land animals like caribou. Among these, fish hold a central role in daily subsistence and ceremonial life. The practice of using every part of the animal reflects not only practical adaptation to harsh climate environments but also a spiritual ethic: animals are considered sentient beings and partners in survival, rather than mere resources. Waste is viewed as a form of disrespect that can jeopardise future fishing success, as it may offend the animal’s spirit or disrupt the balance of human–animal relations [2].

This ethic of respect is made visible in the comprehensive use of each fish harvested. The meat provides vital nutrition; the oil is used for tanning skins and waterproofing materials, preserving them against the Arctic climate. Internal organs, usually overlooked, are repurposed; for instance, fish bladders are processed into glue. The skin is transformed into garments, kayak coverings, tents, and containers, while bones are fashioned into sewing tools. Each transformation of material reflects not only technical ingenuity but also a worldview that sees human survival as entangled with the lives and bodies of animals.

Moreover, fish by-products not only are practical materials but also convey cultural meaning. Clothing, footwear, and containers made from fish skin signal age, gender, status, or ritual role. For instance, specific garment styles or decorations mark life stages, distinguish men’s and women’s gender, or indicate clan affiliation. In ceremonial contexts, fish skin items provide spiritual protection. These meanings are encoded in the choice of fish species, construction techniques, and decorative elements, making such artefacts expressions of identity and tradition [2]. These items undergo processes such as tanning, dyeing, and sewing, which themselves are knowledge-rich practices passed down across generations. In this way, the fish is not only respected through its full use but also honoured by being a vital part of community knowledge.

The following examples illustrate how these values are used through material practices involving fish by-products in clothing and containers.

8.1. Fish Skin: Durable, Lightweight, and Spiritually Charged

Salmon was a key food source integral to the diets of Sugpiaq, Athabascan, Iñupiaq, Tlingit, Yup’ik, and Inuit communities in Alaska [38]. Fish skin, prized for its durability and lightweight qualities, was used historically across Alaska by Inuit cultures extending from Prince William Sound on the Pacific coast of Alaska to the Bering Strait [16].

Alaska Native women used salmon skins to create parkas (Figure 5A), boots, mittens (Figure 5B), bags (Figure 5C), blankets, and tents [39].

Figure 5.

(A) Yup’ik pike skin parka for child, Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI), Washington, DC, USA. (B) Fish skin mittens, Smithsonian National Museum of American Indian, Washington, DC, USA. (C) Fish skin container, Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, Washington, DC, USA. Photographs: Elisa Palomino.

Smithsonian collector Edward Nelson [12] observed in the 1880s that Lower Yukon communities used salmon skins to make garments, and Reverend Sheldon Jackson noted that the Natives of Kodiak Island made shirts out of the skins of codfish and salmon during the same period. In the early 20th century, Cornelius Osgood documented the Deg Hit’an Athabascan People’s production of fish skin garments and bags [13]. Frederica de Laguna later recorded Tlingit use of halibut skin bags in the Yakutat area in the 1950s [14].

Chum salmon skin was favoured for garments, while species like whitefish, blackfish, and Arctic char were also common [21]. Thinner-skinned fish, such as burbot, served as window coverings [40], and eel skins were valued for bags and garments [12,18].

In the 18th century, Alaska Native wardrobes included garments crafted from fish skins, bird skins, and gut skins, alongside sea otter, seal, and caribou hides. Women worked through the winter months, illuminated by oil lamps, to create these durable and decorated items. Women made windproof salmon skin parkas, which were multifunctional as blankets, beds, or makeshift shelters [41]. These parkas were highly valued, exchanged as trade items, gifts, or wartime spoils, and adopted by Arctic explorers for their practicality.

For Alaska Native Peoples, garments are expressions of the women’s creativity and serve as talismans that connect humans to animals [42]. Fish skin parkas, used in shamanistic ceremonies, were both functional and symbolic, forging a spiritual bond between the shaman and the underworld [17].

Fish skin footwear was designed to meet the demands of Arctic conditions [14]. Fish skin is highly breathable—more so than conventional leathers and synthetics—and naturally antibacterial. These properties were known among the Ainu (Figure 6A), Hezhe, Alaska Native, and Siberian communities, who crafted boots suited for insulation and mobility. The function of fish skin footwear was not only to protect the feet from cold and wet conditions but also to support comfort and movement across varied terrains [2]. These qualities of fish skin have continued to influence contemporary design. In the 1940s, wartime rationing limited access to traditional leathers, prompting designers to explore alternative materials. Salvatore Ferragamo began using fish leather (Figure 6B) in his footwear during the late 1920s, responding both to the appeal of novel textures and later on to material scarcity [43]. Similarly, in 2006, Nike launched a sneaker collection (Figure 6C) using perch leather from Icelandic tannery Atlantic Leather, which produces fish leather using skins discarded by the food industry and takes advantage of the material’s strength and breathability. I investigated these properties through material performance tests conducted during my doctoral research, assessing the higher breathability of fish skin in comparison to conventional leathers and synthetic materials [2].

Figure 6.

(A) Salmon skin boots, Ainu, Hokkaido, Japan. NMNH, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, USA. Photograph: Elisa Palomino. (B) Salvatore Ferragamo, pump, 1930–1935, turquoise-dyed snapper leather. Courtesy of Museo Ferragamo, Florence. Photograph: Christopher Broadbent. (C) Nike sneakers made of perch leather from Atlantic Leather tannery. Photograph: Elisa Palomino.

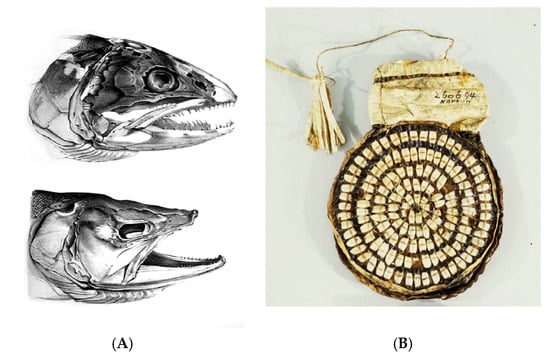

8.2. Fish Heads: Enhancing Fishing Success

The Greenlandic Inuit, who are descendants of the Inuit that migrated from Alaska around the 1300s, also used secondary fish resources in practical and spiritual ways. Summer fishing was vital for winter subsistence, particularly when adverse weather limited access to sealing, whaling, and fishing grounds. Capelin (Mallotus villosus), locally known as ammassak, were especially important due to their seasonal abundance. These small nutrient-rich fish formed dense shoals along the eastern Greenlandic coastline and were traditionally harvested using scoops, a method that allowed for efficient collection during spawning periods [44].

The importance of capelin extended beyond nutrition. The fish’s presence shaped not only seasonal harvesting patterns but also cultural identity, as seen in regional place names. Settlements such as Ammassalik—literally “the place with capelin”—signal both ecological abundance and the cultural salience of the species. Another place, Ammassaataasaq, translates as “the place resembling a bag of dried capelin,” suggesting both the presence of the fish and the connection between everyday objects and the landscape and memory of the region [45].

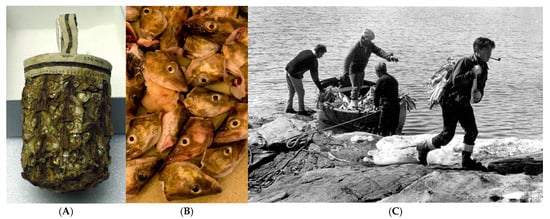

Beyond subsistence, capelin also held spiritual value. After being skinned, the fish heads were dried and used to decorate small carrying bags (Figure 7A), a practice that reflected the integration of natural materials into household items. These decorated bags were used not only for storing food but also as part of broader fishing practices, since including capelin heads (Figure 7B) in the design of these bags would invoke the spirit of the capelin, attracting future catches (Figure 7C) through connecting with the animal’s essence [46]. Unfortunately, their organic composition has meant that few historical examples have survived.

Figure 7.

(A) Ammassak fish head bag, Nuuk, Greenland. Smithsonian NMNH. Photograph: Elisa Palomino. (B) Fish heads at the Royal Greenland cod processing factory. (C) Dried cod being taken off the boat, 1968. Ammassalik Museum, Greenland.

Women were central to these practices, being responsible for the full cycle of capelin processing—from catching and drying to preparing fish for winter storage. Their expertise not only ensured the community’s survival during the winter but also maintained the cultural continuity of ecological knowledge and ritual practice associated with local marine resources [44].

8.3. Fish Oil: Traditional Tanning Techniques and Waterproofing Innovations

The early Indigenous Arctic Peoples developed traditional tanning methods, according to local resources. Skins could be mechanically softened without tanning solutions or treated with three main groups of tanning materials: fats, vegetable substances, and minerals. Animal-derived materials such as urine, brains, liver, kidneys, bone marrow, fish oil, and fish roe were used alongside vegetable-based options like tree bark, leaves, and gallnuts, sometimes in combination [21].

Oil tanning involves the penetration of fatty substances into the fibrous structure of the skin, where the oils oxidise and bond with the fibres. It is considered one of the oldest tanning techniques, usually employed alongside smoke tanning [2]. This technique may have been discovered by the Inuit, who had access to oils from whales, fish, and seals [47].

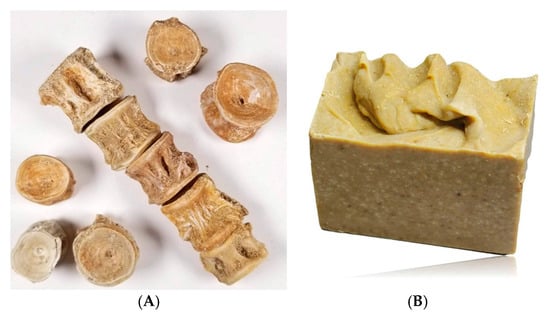

Erman notes that fish skins treated with fat became airtight and durable, offering waterproof qualities in snowy or rainy conditions [15]. Steinbright [48] describes the Athabaskan method of tanning skins using a mixture of boiled fish vertebrae (Figure 8A) oil and sudsy soap (Figure 8B). Fish oils were also used to waterproof canoes and fish skin shoes, demonstrating advanced Indigenous knowledge of science and technology.

Figure 8.

Tanning skins using a mixture of boiled (A) fish vertebrae and (B) sudsy soap.

In the Aleutian Islands, lukewarm shark liver oil was used to treat sea lion skins for kayak construction [49]. Alaska Natives at Point Barrow treated skins with train oil derived from whale blubber, softening them and making them waterproof, particularly for boot soles [50]. Women wore waterproof boots made of king salmon skin smeared with seal oil, which prevented water absorption and gave the skins a transparent quality [51].

The oil tanning practices employed by early Indigenous Arctic communities, tailored to the availability of local resources, find contemporary resonance in the efforts of modern tanneries to adopt vegetable tanning methods for fish leather using bark extracts. Compared to the potentially hazardous and non-biodegradable chrome tanning, which continues to be deposited in landfills and oceans to harmful effect, vegetable tanning requires a higher amount of tannins and generates effluents that require more intensive treatment before disposal. However, it offers the advantage of using natural, renewable, and environmentally sustainable raw materials [52].

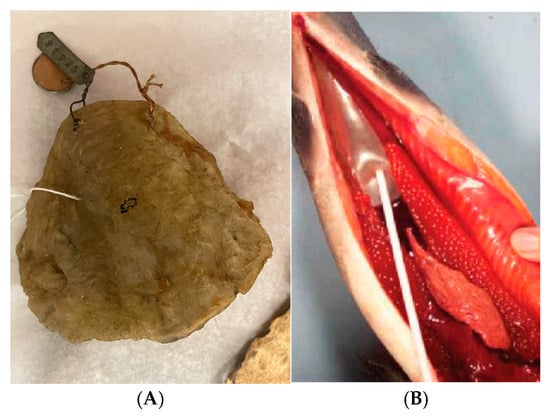

8.4. Fish Glue: A Transparent Bond, Crafted from the Collagen of Swim Bladders

Isinglass, commonly known as fish glue, is a type of collagen obtained by boiling the connective tissue of skins, bones, tendons, and other tissues, similar to gelatine [4]. The English term “isinglass” originates from the Dutch word huizenblaas, where huizen refers to a type of sturgeon and blaas means bladder [53]. Traditionally, the highest-quality fish glue was made from the swim bladders of sturgeons native to the freshwater of the Caspian and Black seas [54].

In North America, isinglass (Figure 9A) is made from cod or hake. The production process involves removing the air bladders (Figure 9B) from the fish, cleaning them, air-drying them, boiling them, and transforming them into a highly effective adhesive. Once dried, the bladders are cut into thin, translucent strips. These strips, composed of nearly 80% collagen, are then dissolved in hot water, diluted, and cooled into flat disks [55]. Fish glue is transparent, colourless, and water-soluble, and can bond materials strongly, drying with a shiny finish [4].

Figure 9.

(A) Fish bladder glue. Néprajzi Múzeum, Budapest, Hungary. Photograph: Elisa Palomino. (B) Salmon swim bladder.

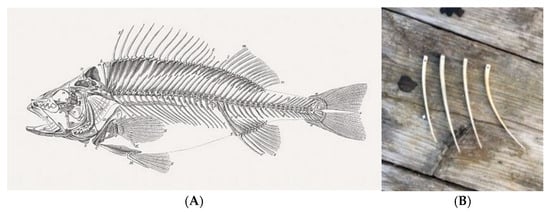

8.5. Fish Bones: Crafting Needles and Tools

Historically, fish bones (Figure 10A) were used to craft needles (Figure 10B), along with reindeer, bird, and other animal bones. Today, commercial steel needles are used instead. These needles were either carved with a notch for threading or drilled using a mouth bow drill. Fish bones found in early Greenlandic Thule houses may have been used as awls or pins for very light sewing work [56], while larger bone needles and awls were used to sew thicker skins such as walrus or moose [15,19,23].

Figure 10.

(A) Fish skeleton. (B) Fish bones carved as awls for sewing.

8.6. Fish Vertebrae: Beads of Adornment and Amulets

Ceremonial treatment of animal remains is well recorded among Inuit, with intentional ritual disposal of marine mammals reflecting a worldview that respected the spirits of hunted animals. Among the Yupik, bones from trap-caught fish were ritually disposed in ways that prevented dogs from eating them, suggesting ritual concern with how remains were handled [57]. A unique find of four char vertebrae strung on a baleen cord from a Thule house at Cape Kent in northern Greenland may represent its use as an amulet [58], but widespread ritual treatment of fish bones is not evident in archaeological finds. However, Birket-Smith [59] describes a toy made of thirteen fish cranial bones.

Inuit have long decorated clothing using local materials available, such as animal skin fringes and bone, ivory, and fur appliqués [20]. Before European contact, Alaska Inuit produced beads from shells and stones and adorned skin garments with porcupine quills or painted motifs [60]. Archaeological finds from Kodiak Island indicate that fish vertebrae were also modified for use as beads [32]. Beads made from bone, ivory, and fish vertebrae served both as decoration and protective amulets. Long before the introduction of European glass beads in the seventeenth century, tiny vertebrae beads coloured with blood and berry juice were arranged into patterns and worn on garments, shoes, and mittens [61]. These beaded patterns expressed identities and affiliations across Inuit communities [62].

Greenlandic Inuit women produced beads from locally sourced materials such as the vertebrae of ammassak. These vertebrae were strung on leather thongs and worn as necklaces or ornaments to secure women’s long hair atop the head. Men similarly used the vertebrae of ammassak, incorporating them into hairbands or leather straps across the chest to which amulets were affixed. These amulets promoted longevity and hunting success [35]. The way Greenlandic women transformed the tiny bones of ammassak into embellishments reveals how the smallest remains held protective powers.

Today, the spiritual and ecological significance of vertebrae persists in contemporary practices. Rika Mouw, an artist from Alaska’s Kenai Peninsula, creates environmental jewellery (Figure 11A) using coiled fish vertebrae (Figure 11B). Her work draws attention to the fragility of marine ecosystems, addressing themes such as ocean acidification, oil drilling, and overfishing. Her pieces, made in Homer, encourage reflection on the connections between humans and the natural world [63].

Figure 11.

(A) Salmon vertebrae jewellery by artist Rika Mouw, created as a response to environmental concerns. (B) Detail of fish vertebrae used in ornamentation.

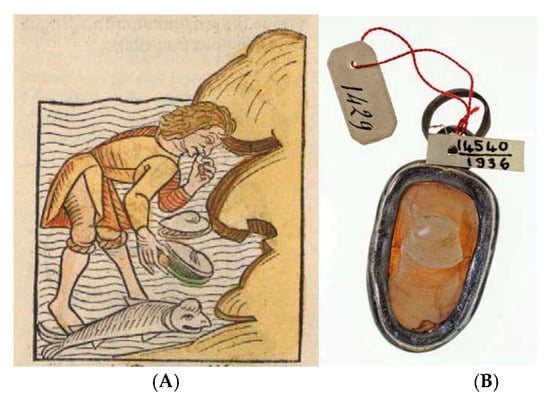

8.7. Fish Otoliths: Lucky Stones, Amulets, and Cultural Embellishments

Fish otoliths, the ear bones of fish (Figure 12A), were historically used for jewellery, protective amulets, and trade. Otoliths, composed of calcium carbonate, are crucial for balance and hearing in fish. Marine biologists use them to determine the age and growth of fish, akin to tree rings. These structures differ between fish species, allowing researchers to identify them from archaeological sites. Otoliths also provide ecological and anthropological insights into fish habitats and human usage [64].

Figure 12.

(A) Fish otoliths inside salmon heads. (B) Gutskin bag decorated with otoliths. Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, Washington, DC, USA. Photograph: Elisa Palomino.

Otoliths, considered “lucky stones,” were used as charms and traded in Pre-Contact times as far as Utah and California and were found at ancient archaeological sites. The large otoliths of the freshwater drum (Aplodinotus grunniens) were particularly valued [65]. These stones, originally white, darken with age (Figure 12B), and are associated with protection and good fortune.

Birket-Smith [59] reports a men’s brow band (Figure 13A) made of depilated caribou skin, decorated with 43 otoliths strung on a sinew line, while Rasmussen [66] notes the use of such brow bands with decorations of brass or iron by Copper Eskimo men and women. A Thule ivory carving of a man (Figure 13B) excavated north of Nome, Alaska, shows an incised line around the perimeter of the scalp depicting a brow-band in a style known to be worn by Thule men. Additional engraved details delineate a belt at the waist and a triangular fur loincloth in front [67]. Caribou skin belts decorated with otoliths (Figure 13C) have also been worn as protective amulets to ward off illness. Issenman [37] mentions that Greenland Inuit used ammassak vertebrae and cod otoliths for clothing adornment.

Figure 13.

(A) Brow-band of depilated caribou skin decorated with 43 fish otoliths [59]. (B) Thule marine mammal ivory carving of a man, Western Alaska, 1200–1700 CE. (C) Baby’s belt decorated with otoliths. University of Alaska Museum of the North, Fairbanks. Photograph: Elisa Palomino.

The use of otoliths as adornment within Inuit contexts connects with a wider human engagement with these materials. Since Aristotle first noted the presence of stones in fish heads, and Cuvier later identified their morphological features as otoliths, they were employed in classical antiquity in weather divination (otolithomancy) and in traditional medicine (Figure 14A) to treat kidney stones, jaundice, malarial fever, nosebleeds, and other ailments [68]. Otoliths were also used in treatments related to fertility and vitality. The otoliths of the European sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax), known as Perles de maigre, were mounted in gold and worn in early modern Spain (Figure 14B) as protective amulets against fever [69]. In seventeenth-century Brazil, healers used them in ritual medicine to treat kidney conditions [70]. These practices continued into the eighteenth century and still persist in some communities today in the treatment of urinary tract infections, fever, and respiratory ailments [68].

Figure 14.

(A) Illustration of a beached fish containing an otolith, from a hand-coloured edition of the Hortus Sanitatis (1491), one of the earliest printed herbal encyclopaedias. (B) Spanish otolith amulet, Pitt-Rivers Museum, Oxford.

9. Arrival of New Materials in the North

With the arrival of explorers, merchants, and trade networks, Inuit communities began incorporating new materials and techniques. Objects such as spoons, ammunition, coins, wood, lead, brass, and beads were introduced into the North. European glass beads (Figure 15A) were available as early as 1685 at the Fort Churchill trading post and were quickly embraced by Indigenous groups. In the eastern Arctic, they were known as sapangait (Ungava Bay) or pilutiit (Hudson Bay), and along with silk ribbons and wool were quickly integrated into Inuit adornment practices (Figure 15B). Beads were used on garments such as the qalliniit (uppers) on kamiik and the savviguti (beaded breastplate) on the amauti [58].

Figure 15.

(A) Opaque, turquoise-coloured glass beads excavated in Arctic Alaska [71]. (B) Beaded moose skin cushion, interior Alaska, University of Alaska Museum of the North, Fairbanks, Alaska. Photograph: Elisa Palomino.

The Danish colonisation of Greenland also brought a wider assortment of beads, which were distributed through whalers and the Danish Royal Greenland Trading Company. Though never inexpensive, imported beads eventually became a key component of Greenlandic women’s festive national dress [35].

Archaeological evidence from Karluk on Kodiak Island has yet to confirm the presence of glass beads before the eighteenth century, but their use by other Indigenous nations centuries earlier raises the possibility of earlier circulation among the Sugpiat [32]. Inuit groups traded walrus ivory, whale baleen, eider down, and seal and walrus hides for European goods such as iron tools, cloth, tobacco, beads, and ceramics. These imported items were then carried north to settlements inaccessible to European ships. Fitzhugh [72] notes that the introduction of iron tools, copper pots, and glass beads not only changed Inuit lifeways but also aids archaeologists in dating post-contact sites.

The advent of glass beads also marked a cultural shift in how Inuit women expressed their art. In the Canadian Arctic, sapangaq or “precious stones” were considered prestigious and desirable trade items. Captain George Lyon, writing in 1824, observed that women in Iglulik were already incorporating beads into garments when his expedition arrived in 1821. Decorative motifs began to reflect the growing influence of outside trade, and the design of clothing played an increasingly important role in the development of contemporary Inuit graphic art [73]. Some women travelled vast distances—up to 777 km—to access trade posts such as Fort Churchill. According to Captain George Comer’s 1903–1905 journal, his whaling ship carried 25 pounds of sungaujait and 11,000 needles, noting that Inuit “have a good passion for small glass beads of different colors” [62]. Testimonies such as that of Arsenti Aminak also capture early Indigenous responses to these materials. Aminak recalls the Sugpiaq mariner Ishinik returning from contact with Russian promyshlenniki, bringing back glass beads as part of their trade offerings. While some Elders expressed scepticism, they agreed to engage with the newcomers if the exchange offered a “good price for our skins” [74]. The widespread movement of beads and their rapid adoption across the North highlights their integration into Inuit cultural material and illustrates how, throughout history, Indigenous and non-Indigenous cultures have served as mutual sources of inspiration and exchange.

Archaeologists in northern Alaska have uncovered blue glass beads (Figure 15A) that may point to earlier trade connections than previously confirmed. These beads could have been made in Venice, travelled east along the Silk Roads, and eventually crossed Eurasia and the Bering Strait to reach Alaska. Radiocarbon dating of twine made of organic material found with the beads suggests they were made between 1397 and 1488. This find suggests that long-distance trade networks may have reached the region well before European contact, offering new insights into early global exchange [71,75].

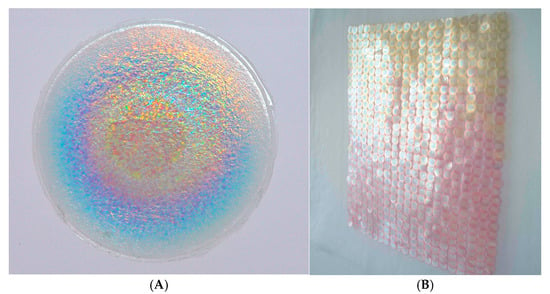

Today, the environmental consequences of synthetic adornment, such as plastic sequins, have prompted renewed interest in sustainable alternatives. Designer Elisa Brunato has developed bio-iridescent sequins from tree-derived cellulose (Figure 16A), offering an eco-conscious material for fashion (Figure 16B). These bioplastic embellishments recall earlier practices such as the use of otoliths and fish vertebrae by Alaska Native communities to decorate garments and accessories [76].

Figure 16.

(A) Bio-iridescent sequin by Elisa Brunato as a response to unsustainable plastic sequins currently used in fashion. (B) Through extracting the crystalline form of cellulose, the wood imitates shiny plastic while remaining lightweight, strong, and compostable.

10. Conclusions

Since humans and fish coexist on the same planet, the development of a fish skin culture was therefore inevitable. Throughout history, humans have used the materials available in their immediate environment, making the most of animal remains. Animal skins have been used to provide body warmth and protection and been transformed into containers for food preservation, while fish leftovers have been turned into ornaments. The relationship between humans and fish goes back a long way, and a fish skin culture emerged as a result.

This paper has explored the role of fish and fish by-products in the material culture of Alaska Native and Greenlandic Inuit communities, highlighting how fish skin, heads, bones, bladders, oils, and otoliths have been transformed into clothing, tools, adhesives, organic tanning agents, and adornment. These practices reflect the ecological knowledge and resourceful use of local materials, with direct relevance to current sustainability challenges in the fashion and design sectors.

Subsistence fishing remains central to Alaska Native and Greenlandic Inuit life, not only as a food source but also as a practice rooted in seasonal rhythms and interdependent relationships with land and water. The crafting of garments from fish skin by Alaska Natives, which is highly durable, wind-resistant, and breathable, illustrates a form of material innovation that predates industrial outerwear materials. The process of tanning fish skin with fish oil, without the use of harsh chemicals such as chrome, aligns with modern efforts to reduce toxic waste in leather production. In recent years, fashion designers and material researchers have increasingly turned to fish leather and other bio-based materials as alternatives to petroleum-based synthetics. These practices form part of a living cultural heritage—not simply technical processes but also expressions of Indigenous worldviews, spiritual values, and ecological ethics. Far from being remnants of the past, they continue to inform contemporary approaches to sustainable material use.

The incorporation of fish bones, otoliths, and vertebrae into wearable objects also speaks to a zero-waste ethos. What is commonly viewed in industrial contexts as discard material was, in Indigenous contexts, intentionally shaped into amulets, jewellery, or tools. This approach models a closed-loop system that challenges the extractive logics dominant in contemporary fashion.

Furthermore, these practices are part of a worldview that emphasises reciprocity with the environment. Materials are not simply resources but are also understood to carry meaning and agency. This perspective stands in contrast to dominant industrial systems and offers a conceptual shift for sustainability frameworks, which increasingly recognise the need to integrate cultural considerations.

Traditional ecological knowledge has ensured that fish are harvested in ways that support ecosystem health. The sustainability of these practices is not a recent development but rather a reflection of long-standing lifeways. As the fashion industry confronts the limits of globalised production and the environmental cost of fast fashion, the Arctic case offers a grounded, culturally specific model of material use that is efficient, ethical, and enduring. By attending to the knowledge of the use of fish skin and other by-products, as well as the cultural values that shape their transformation, this paper contributes to rethinking contemporary anthropology and sustainable fashion as fields that must draw on Indigenous histories of care, craftsmanship, and ecological balance.

Building on this research, I am currently developing a monograph titled Salmon Entanglements: Crossroads of Fish Skin Material Culture in Arctic Native Societies, to be published in the Marco Polo. Studies in Global Europe-Asia Connections series at Ca’ Foscari University, Venice. In parallel, I continue to collaborate with Native Elders and fish skin artists through museum-based research and co-creative projects aimed at safeguarding and revitalising this unique cultural heritage.

Funding

This work was supported by EU Horizon 2020-MSCA-RISE-2018 Research and Innovation Staff Exchange Marie Sklodowska-Curie-Actions (MSCA) grant no. 823943: FishSkin Developing Fish Skin as a Sustainable Raw Material for the Fashion Industry; the Fulbright UK US scholar award; the AHRC Kluge Fellowship at the Library of Congress under grant no. AH/X002829/1; a post-doctoral fellowship at the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science in Berlin at Dept. III Artifacts, Action, Knowledge, facilitated by the staff Ellen Garske, Matthias Schwerdt, Sabine Bertram, and Ruth Kessentini; a post-doctoral fellowship at the Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz, the Max-Planck-Institute, and Koç University’s Research Center for Anatolian Civilizations, ANAMED; and a post-doctoral fellowship at the Ca’ Foscari Department of Asian and North African Studies, The Marco Polo (MaP) Centre for Global Europe-Asia Connections.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

This paper builds upon and honours the material cultural heritage developed by Inuit communities across Siberia, North America, and Greenland. Central to this heritage is the knowledge of Inuit women, whose expertise in preparing and sewing fish skin garments enabled survival in some of the planet’s most extreme climates. In collaboration with Elders and fish skin artists—including June Pardue (Sugpiaq/Iñupiaq), Anatoly Donkan (Nanai), Wengfen Yu (Hezhe), Lotta Rahme (Swedish), and Shigehiro Takano (Japanese, engaged with the Ainu community)—this work addresses Indigenous fish skin and fish remnant technologies as models of sustainable practice. I am especially grateful to William Fitzhugh, Igor Krupnik, Stephen Loring, John Cloud, Bernadette Driscoll Engelstad, and Nancy Shorey of the Arctic Studies Center at the National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, as well as Aron Crowell and Dawn Biddison at the Smithsonian Arctic Studies Center, Anchorage Museum.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Stuckenberger, N. Thin Ice: Inuit Life and Climate Change. In Thin Ice: Inuit Traditions Within a Changing Environment; Stuckenberger, N., Ed.; Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College: Hanover, NH, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Palomino, E. Indigenous Arctic Fish Skin Heritage: Sustainability, Craft and Material Innovation. Ph.D. Thesis, University of the Arts, London, UK, 2022. Available online: https://ualresearchonline.arts.ac.uk/id/eprint/20124/ (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Driscoll, B. The Inuit Parka: A Preliminary Study. Master’s Thesis, Carleton University, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1983. Available online: https://curve.carleton.ca/7a5a715f-90d0-440a-a70a-298f23c42733 (accessed on 18 December 2024).

- Olden, J.D.; Vitule, J.R.S.; Cucherousset, J.; Kennard, M.J. There’s More to Fish Than Just Food: Exploring the Diverse Ways That Fish Contribute to Human Society. Fisheries 2020, 45, 453–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rix, E.F.; Wilson, S.; Sheehan, N.; Tujague, N. Indigenist and Decolonizing Research Methodology. In Handbook of Research Methods in Health Social Sciences; Liamputtong, P., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, S. Research Is Ceremony: Indigenous Research Methods; Fernwood Publishing: Halifax, NS, Canada, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Palomino, E.; Pardue, J. Alutiiq Fish Skin Traditions: Connecting Communities in the COVID-19 Era. Heritage 2021, 4, 4249–4263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomino, E.; Pardue, J.; Donkan, A. Fish Skin Peoples of the Bering Strait: Encounters in Hokkaido, Japan. Arctic Studies Center Newsletter, Smithsonian Institution National Museum of Natural History: Washington, DC, USA, 2023; Volume 30, pp. 74–75. [Google Scholar]

- Palomino, E.; Boon, J. Preservation of Hezhen Fish Leather Tradition through Fashion Education. In Textiles, Identity and Innovation; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Palomino, E.; Zhang, Z. Preservation of Hezhen Fish Skin Tradition Through Fashion HE: Fashion Film Festival Milano 21 Best Green Fashion Film. 2020. Available online: https://fashionfilmfestivalmilano.com/project/preservation-of-hezhen-fish-skin-tradition-through-fashion-higher-education-2021/ (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- Palomino, E.; Rahme, L. Indigenous Arctic Fish Skin—A Study of Different Traditional Skin Processing Technology. J. Soc. Leather Technol. Chem. 2021, 105, 59–71. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, E.W. The Eskimo about Bering Strait. In Eighteenth Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution; Powell, J.W., Ed.; Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 1899; pp. 19–526. [Google Scholar]

- Osgood, C. Ingalik Material Culture; Yale University Publications in Anthropology 22; Oxford University Press: London, UK, 1940; pp. 3–500. [Google Scholar]

- Jackinsky-Sethi, N. Fish Skin as a Textile Material in Alaska Native Cultures. First Am. Art Mag. 2014, 5, 40–47. [Google Scholar]

- Hatt, G.; Taylor, K. Arctic Skin Clothing in Eurasia and America: An Ethnographic Study. Arct. Anthropol. 1969, 5, 3–132. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzhugh, W.W.; Kaplan, S.A. Inua: Spirit World of the Bering Sea Eskimo; Smithsonian Institution Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Hickman, P. Innerskins and Outerskins: Gut and Fish Skin; Craft and Folk-Art Museum: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- VanStone, J.W. Nunivak Island Eskimo (Yuit) Technology and Material Culture. Fieldiana Anthropol. New Ser. 1989, 12, i–v, vii–viii, 1–108. [Google Scholar]

- Oakes, J.; Riewe, R. Spirit of Siberia: Traditional Native Life, Clothing, and Footwear; Smithsonian Institution Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Buijs, C. Furs and Fabrics: Transformations, Clothing and Identity in East Greenland; Mededelingen van het Rijksmuseum voor Volkenkunde; CNWS Publications: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Reed, F. The Poor Man’s Raincoat: Alaskan Fish-Skin Garments. In Arctic Clothing; King, J.C.H., Pauksztat, B., Storrie, R., Eds.; British Museum Press: London, UK, 2005; pp. 48–52. [Google Scholar]

- Vávra, R. Fish and Chaps: Some Ethnoarchaeological Thoughts on Fish Skin Use in European Prehistory. Open Archaeol. 2020, 6, 329–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaussonnet, V. Crossroads Alaska: Native Cultures of Alaska and Siberia; Arctic Studies Center, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution: Washington, DC, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Chaussonnet, V. Needles and Animals: Women’s Magic. In Crossroads of Continents: Cultures of Siberia and Alaska; Fitzhugh, W.W., Crowell, A., Eds.; Smithsonian Institution Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1988; pp. 209–226. [Google Scholar]

- Buijs, C.; Petersen, M. Festive Clothing and National Costumes in 20th Century East Greenland. Études/Inuit/Stud. 2004, 28, 83–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Harvey, E. Meet Elisa Palomino. 2020. Available online: https://www.arts.ac.uk/alumni-and-friends/stories/meet-elisa-palomino (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Minney, S. Regenerative Fashion and Just Transition Report. Available online: https://safia-minney.com/regenerative-fashion-and-just-transition-report-2/ (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Lincoln, A.; Laurens Loovers, J.P. Relations with Animals in the Circumpolar North. In Arctic: Culture and Climate; Lincoln, A., Cooper, J., Laurens Loovers, J.P., Eds.; Thames and Hudson: London, UK, 2020; pp. 44–77. [Google Scholar]

- France, T. Finding Common Ground on the Lower Snake River. Available online: https://blog.nwf.org/2020/11/finding-common-ground-on-the-lower-snake-river/ (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Fienup-Riordan, A.; Rearden, A.; Meade, M.; Chanar, D.R.; Nayamin, R.; Joseph, C. Nunakun-gguq Ciutengqertut/They Say They Have Ears Through the Ground: Animal Essays from Southwest Alaska; University of Alaska Press: Fairbanks, AK, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, J. The Arctic Experience of Climate Change. In Arctic: Culture and Climate; Lincoln, A., Cooper, J., Laurens Loovers, J.P., Eds.; Thames and Hudson: London, UK, 2020; pp. 18–28. [Google Scholar]

- Steffian, A.F.; Laktonen Counceller, A.G. Alutiiq Traditions: An Introduction to the Native Culture of the Kodiak Archipelago; Alutiiq Museum and Archaeological Repository: Kodiak, AK, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, R. The Alutiiq Ethnographic Bibliography; Alaska Humanities Forum: Anchorage, AK, USA, 1995; Available online: http://ankn.uaf.edu/ancr/Alutiiq/RachelMason/index.html (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Park, R.W. The Thule Migration: A Culture in a Hurry? Open Archaeol. 2023, 9, 20220326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buijs, C. Clothing from East Greenland; National Museum of Ethnology: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, A.L. An Analysis of 600-Year-Old Gut-Skin Parkas of the Early Thule Period from the Nuulliit Site, Avanersuaq, Greenland. Arct. Anthropol. 2024, 59, 107–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issenman, B.K. Sinews of Survival: The Living Legacy of Inuit Clothing; University of British Columbia Press: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, D.D. Prehistory of North Alaska. In Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 5: Arctic; Damas, D., Ed.; Smithsonian Institution: Washington, DC, USA, 1984; Volume 5, pp. 80–93. [Google Scholar]

- Golovnev, A.V. Reindeer Herders and Mobility. In Arctic: Culture and Climate; Lincoln, A., Cooper, J., Laurens Loovers, J.P., Eds.; Thames and Hudson: London, UK, 2020; pp. 82–99. [Google Scholar]

- Stefánsson, V. The Stefánsson-Anderson Arctic Expedition of the American Museum: Preliminary Ethnological Report. Anthropol. Pap. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist. 1914, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Liapunova, R. Essays on the Ethnography of the Aleuts: At the End of the Eighteenth and the First Half of the Nineteenth Century; University of Alaska Press: Fairbanks, AK, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Steffian, A.; Leist, M.; Haakanson, S., Jr.; Saltonstall, P. Kal’unek. From Karluk: Kodiak Alutiiq History and the Archaeology of the Karluk One Village Site; University of Alaska Press: Fairbanks, AK, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ricci, S. Materiali per la Fantasia; Museo Salvatore Ferragamo: Firenze, Italy, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Mirsky, J. The Eskimo of Greenland. In Cooperation and Competition Among Primitive Peoples; Mead, M., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Danish Geodata Agency. Greenland Pilot: Explanations of the Place Names. Available online: https://eng.gst.dk/media/9097/gp-explanations-of-the-place-names_2015_skr_27_2020.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Kaalund, B. The Art of Greenland; University of California Press: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Trommer, B. Archäologisches Leder. Herkunft, Gerbstoffe, Technologien, Alterungs- und Abbauverhalten; Verlag Dr. Müller: Saarbrücken, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Steinbright, J. From Skins, Trees, Quills, and Beads: The Work of Nine Athabascans; Institute of Alaska Native Arts: Anchorage, AK, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Hrdlicka, A. The Aleutian and Commander Islands and Their Inhabitants; Wistar Institute of Anatomy and Biology: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1945. [Google Scholar]

- Murdoch, J. Ethnological Results of the Point Barrow Expedition. Ninth Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology, 1887–1888; Bureau of American Ethnology: Washington, DC, USA, 1893; pp. 3–441. [Google Scholar]

- Fienup-Riordan, A. Yuungnaqpiallerput the Way We Genuinely Live: Masterworks of Yup’ik Science and Survival; University of Washington Press: Seattle, WA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Nera. Biodegradability and Disintegration of Leather, 2021. Available online: https://www.neratanning.com/biodegradable-leather/?gad_source=1&gad_campaignid=12206035170&gclid=Cj0KCQjwkILEBhDeARIsAL--pjwUdVjaipsVDNRgHsCYcxKgyhP4fgBtluoSxCtFUHj8ZPr9nuZW-LcaAnNKEALw_wcB (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Talbot, F.L. The Natural History of Isinglass. J. Inst. Brew. 1905, 11, 508–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petukhova, T. A History of Fish Glue as an Artist’s Material: Applications in Paper and Parchment Artifacts. Book Pap. Group Annu. 2000, 19. Available online: https://cool.culturalheritage.org/coolaic/sg/bpg/annual/v19/bp19-29.html (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Koochekian, A.; Ghorban, Z.; Yousefi, A. Production of Isinglass from the Swim Bladder of Sturgeons. J. Appl. Ichthyol. 2006, 22, 419–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giddings, J.L. Ancient Men of the Arctic; University of Washington Press: Seattle, WA, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Whitridge, P. Zen Fish: A Consideration of the Discordance between Artifactual and Zooarchaeological Indicators of Thule Inuit Fish Use. J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 2001, 20, 3–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenness, D. The Life of the Copper Eskimos; Report of the Canadian Arctic Expedition 1913–1918, Volume XII, Part A; F. A. Acland, Printer to the King’s Most Excellent Majesty: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1922. [Google Scholar]

- Birket-Smith, K. Ethnographic Collections from the Northwest Passage; Report of the Fifth Thule Expedition 1921–1924, Volume VI, No. 2; Gyldendalske Boghandel, Nordisk Forlag: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1945. [Google Scholar]

- Mundell, K.; Neptune, J. Colby College Museum of Art. Wíw[ä]nikan: The Beauty We Carry; Colby College Museum of Art: Waterville, ME, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Beads Around the World. Inuit/Greenland. Available online: http://beadsaroundtheworld.com/inuit-greenland/ (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Ulujuk Zawadski, K. Glass Beads in Inuit Needl ework from Past to Present. Inuit Art Q. 2019, Special Venice Issue. Available online: https://www.inuitartfoundation.org/iaq-online/glass-beads-in-inuit-needlework-from-past-to-present (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Engelhard, M. The Natural Talent of Artist Rika Mouw. Alaska Magazine. Available online: https://alaskamagazine.com/authentic-alaska/the-natural-talent-of-artist-rika-mouw/ (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Canadian Museum of Nature. The Rocks in Fishes’ Heads Tell Amazing Stories. Available online: https://nature.ca/en/the-rocks-in-fishes-heads-tell-amazing-stories/ (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Hudson, W. Lucky Stones. Neo-Naturalist.com. Available online: http://www.neonaturalist.com/ (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Rasmussen, K. The Netsilik Eskimos: Social Life and Spiritual Culture; Report of the Fifth Thule Expedition 1921–1924, Volume VIII (1–2); Glydendalske Boghandel Nordisk Forlag: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1931. [Google Scholar]

- Schledermann, P.; McCullough, K. Western Elements in the Early Thule Culture of the Eastern High Arctic. Arctic 1980, 33, 833–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffin, C.J. Fish otoliths and folklore: A survey. Folklore 2007, 118, 78–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piques, G. La cinaedia, pierre précieuse dans la tête d’un poisson. In Thermae Gallicae. Les Thermes De Barzan (Charente-Maritime) Et Les Thermes Des Provinces Gauloises; Bouet, A., Ed.; Ausonius: Bordeaux, France, 2003; pp. 503–506. [Google Scholar]

- Costa-Neto, E.M.; Dias, C.V.; de Melo, M.N. O conhecimento ictiológico tradicional dos pescadores da cidade de Barra, região do médio São Francisco, Estado da Bahia, Brasil. Acta Sci. Biol. Sci. 2002, 24, 561–572. [Google Scholar]

- Kunz, M.L.; Mills, R.O. A Precolumbian Presence of Venetian Glass Trade Beads in Arctic Alaska. Am. Antiq. 2021, 86, 395–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzhugh, W. Some Archaeological Dating Can Be as Simple as Flipping a Coin. Smithsonian Magazine, 20 October 2017. Available online: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/blogs/national-museum-of-natural-history/2017/10/20/some-archaeological-dating-can-be-as-simple-as-flipping-a-coin/ (accessed on 27 May 2025).

- Driscoll, B. Sapangat. Expedition Magazine n.26, January 1984. pp. 40–47. Available online: https://www.penn.museum/sites/expedition/sapangat/ (accessed on 11 August 2024).

- Bancroft, H.H. History of Alaska, 1770–1885; A. L. Bancroft & Company Publishers: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1886. [Google Scholar]

- Venetian Glass Beads May Be Oldest European Artifacts Found in North America. Available online: http://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/tiny-blue-beads-european-artifact-northamericaold-180976966/ (accessed on 8 September 2023).

- Materially. Sequins Made of Cellulose-Based Bioplastic. Available online: https://www.materially.eu/en/sequins-made-of-cellulose-based-bioplastic/ (accessed on 23 May 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).