Diet and Dementia Worldwide: The Role of Meat Fat, Meat Protein, and Development Indicators

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection and Selection

- Biological State Index (Ibs): a measure of genetic predisposition, ranging from 0 to 1, indicating the degree of accumulated deleterious variants due to relaxed natural selection. Higher Ibs values are linked to greater risk of late-onset disorders, including dementia [41].

- Life expectancy at birth (2018): used as a proxy for population aging, obtained from the World Bank [42]. As dementia risk rises steeply with age, life expectancy is a strong contextual factor.

- Urbanization (2018): defined as the percentage of the population living in urban areas, also from the World Bank [39]. Urbanization shapes lifestyle behaviors, including greater meat consumption [34,43], increased availability of processed foods [44], and reduced physical activity [45], and it may also facilitate earlier detection and reporting of dementia.

2.2. Statistical Analyses

- 1.

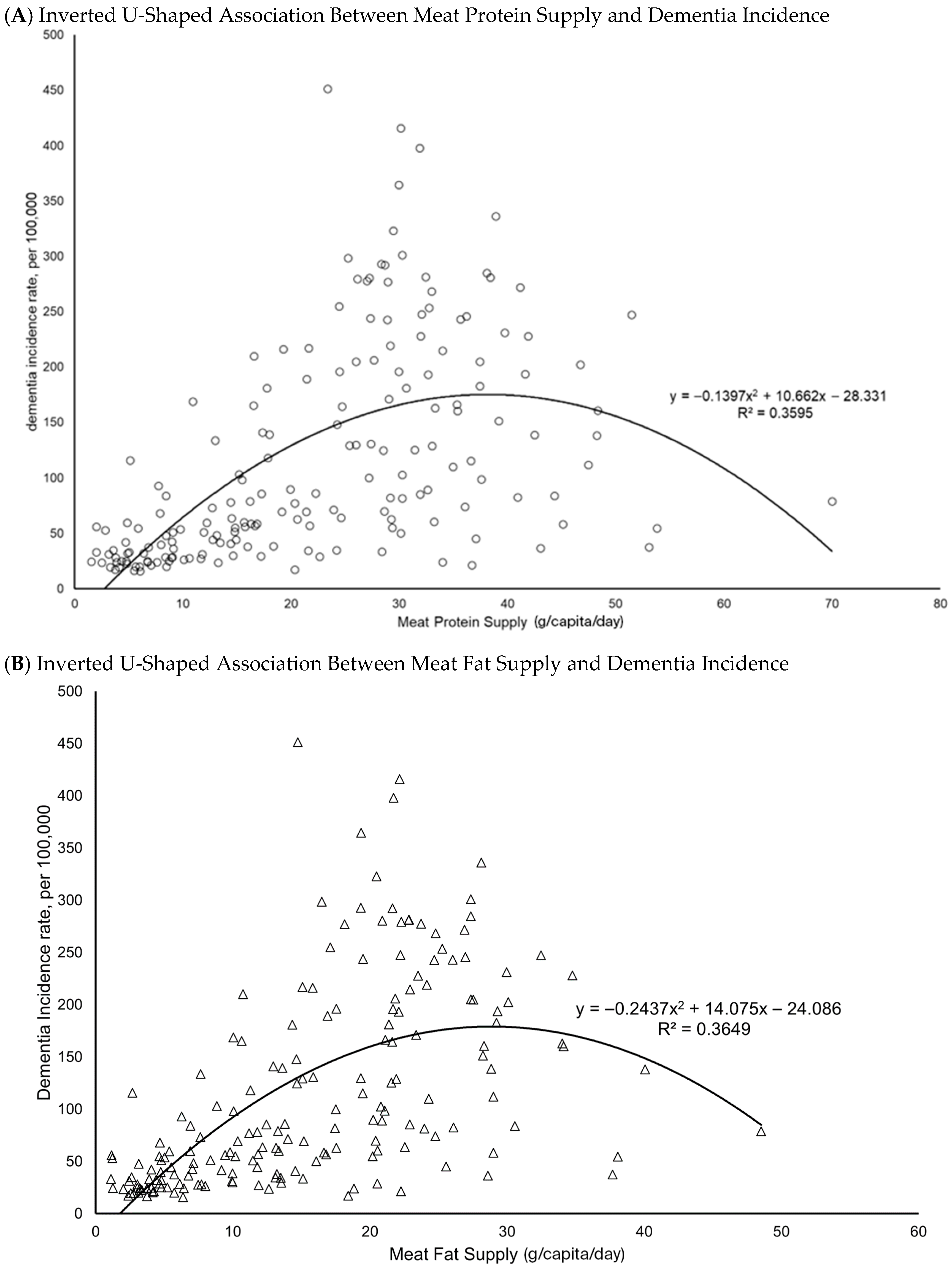

- Initial Data Exploration: Scatterplots were generated using Microsoft Excel® 2016 to visually assess associations between meat protein and fat supply and dementia incidence. This step also identified potential outliers and ensured dataset integrity.Due to non-normal distributions, logarithmic transformation was applied to the six relevant variables for improving their homogeneity for the following bivariate and multiple variate analyses.

- 2.

- Bivariate Correlation Analysis: Pearson’s and nonparametric (Spearman’s rho) correlations were conducted to examine associations among six variables: meat protein supply, meat fat supply, dementia incidence, GDP per capita, Ibs, life expectancy, and urbanization.

- 3.

- Regional Correlation Analysis: Bivariate correlations were extended to subgroup analyses to capture variations across country classifications. Stratifications included:

- ∘

- World Bank income groups (low, lower-middle, upper-middle, high income), with Fisher’s r-to-z transformation comparing high-income with low- and middle-income countries, reflecting WHO’s emphasis on dementia burden in LMICs [1].

- ∘

- United Nations classification (developed vs. developing countries), also compared using Fisher’s r-to-z [50].

- ∘

- WHO regions (Africa, Americas, Eastern Mediterranean, Europe, South-East Asia, Western Pacific) [51].

- ∘

- Cultural and economic groupings such as the Asia Cooperation Dialogue (ACD) [52], Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) [53], the Arab World [54], English-speaking countries (based on government data), Latin America [55], Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) [55], Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) [56], and Southern African Development Community (SADC) [57].

- 4.

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA): PCA was conducted separately for models including meat protein supply or meat fat supply, together with GDP, Ibs, life expectancy, and urbanization, to identify latent factor structures.

- 5.

- Partial Correlation Analysis: Pearson’s partial correlations assessed the independent relationships of meat protein and dementia incidence after sequentially controlling for GDP, Ibs, life expectancy, and urbanization. Analyses were repeated for meat fat supply.

- 6.

- Multiple Linear Regression: Standard (enter) multiple regression was used to evaluate the predictive relationships between dementia incidence (dependent variable) and dietary plus confounding variables. This approach quantified the independent contributions of meat protein and meat fat after accounting for socioeconomic and demographic covariates. Stepwise regression was additionally applied to identify the most significant predictors, with models alternately including or excluding meat protein and fat.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Patterns and Scatterplots

3.2. Correlations and Regression Results

3.2.1. Bivariate Correlations

3.2.2. Regional and Subgroup Analyses

3.2.3. Partial Correlations

3.2.4. Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

3.2.5. Regression Analyses

- Meat protein displayed a weaker and less consistent association (β = 0.14, p = 0.035).

- Meat fat showed a stronger and more consistent independent association (β = 0.17, p = 0.004).

4. Discussion

4.1. Interpretation of Findings

4.2. Comparison with Previous Research

4.2.1. Meat Protein Versus Meat Fat: Clarifying Distinct Roles

4.2.2. Life Expectancy and Development Factors

4.2.3. Multicollinearity and the Nutrition–Development Transition

4.3. Future Directions

5. Conclusions

6. Public Health and Policy Implications

7. Strengths and Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO. Dementia. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Alzheimer’s Disease International. World Alzheimer Report 2015: The Global Impact of Dementia (An Analysis of Prevalence, Incidence, Cost and Trends). 2025. Available online: https://www.alzint.org/u/WorldAlzheimerReport2015.pdf?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- You, W.; Henneberg, R.; Henneberg, M. Healthcare services relaxing natural selection may contribute to increase of dementia incidence. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 8873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingston, G.; Huntley, J.; Sommerlad, A.; Ames, D.; Ballard, C.; Banerjee, S.; Brayne, C.; Burns, A.; Cohen-Mansfield, J.; Cooper, C. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. Lancet 2020, 396, 413–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halliday, G. Pathology and hippocampal atrophy in Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2017, 16, 862–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortega-Cruz, D.; Rabano, A.; Strange, B.A. Neuropathological contributions to grey matter atrophy and white matter hyperintensities in amnestic dementia. Alzheimer Res. Ther. 2025, 17, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butterfield, D.A.; Halliwell, B. Oxidative stress, dysfunctional glucose metabolism and Alzheimer disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2019, 20, 148–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heneka, M.T.; Carson, M.J.; El Khoury, J.; Landreth, G.E.; Brosseron, F.; Feinstein, D.L.; Jacobs, A.H.; Wyss-Coray, T.; Vitorica, J.; Ransohoff, R.M. Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2015, 14, 388–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, G.S. Amyloid-β and tau: The trigger and bullet in Alzheimer disease pathogenesis. JAMA Neurol. 2014, 71, 505–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, M.C.; Tangney, C.C.; Wang, Y.; Sacks, F.M.; Bennett, D.A.; Aggarwal, N.T. MIND diet associated with reduced incidence of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer Dement. 2015, 11, 1007–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnard, N.D.; Bush, A.I.; Ceccarelli, A.; Cooper, J.; de Jager, C.A.; Erickson, K.I.; Fraser, G.; Kesler, S.; Levin, S.M.; Lucey, B. Dietary and lifestyle guidelines for the prevention of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 2014, 35, S74–S78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.H.; Koo, F.K.; You, W.P.; Razaghi, K.; Chang, H.-C.R. Improving nutritional care in residential aged care facilities (RACFs): A scoping review of nutrition education for nursing staff. Nurse Educ. Today 2025, 153, 106789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Razaghi, K.; You, W.; Cheng, Y.; Sun, L.; Wong, I.; Chang, H.-C. Nutritional Status and Feeding Difficulty of Older People Residing in Nursing Homes: A Cross-Sectional Observational Study. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Klipfell, E.; Bennett, B.J.; Koeth, R.; Levison, B.S.; DuGar, B.; Feldstein, A.E.; Britt, E.B.; Fu, X.; Chung, Y.-M. Gut flora metabolism of phosphatidylcholine promotes cardiovascular disease. Nature 2011, 472, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunt, V.E.; Gioscia-Ryan, R.A.; Casso, A.G.; VanDongen, N.S.; Ziemba, B.P.; Sapinsley, Z.J.; Richey, J.J.; Zigler, M.C.; Neilson, A.P.; Davy, K.P. Trimethylamine-N-oxide promotes age-related vascular oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction in mice and healthy humans. Hypertension 2020, 76, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.W.; Wang, Z.; Kennedy, D.J.; Wu, Y.; Buffa, J.A.; Agatisa-Boyle, B.; Li, X.S.; Levison, B.S.; Hazen, S.L. Gut microbiota-dependent trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) pathway contributes to both development of renal insufficiency and mortality risk in chronic kidney disease. Circ. Res. 2015, 116, 448–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Fan, Y.; Yang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Guo, C. Iron and Alzheimer’s Disease: From Pathogenesis to Therapeutic Implications. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liu, D.; Sun, L.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, Z. Advanced glycation end products and neurodegenerative diseases: Mechanisms and perspective. J. Neurol. Sci. 2012, 317, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, W. Global Patterns Linking Total Meat Supply to Dementia Incidence: A Population-Based Ecological Study; AIMS Neuroscience: Beijing, China, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Kesse-Guyot, E.; Andreeva, V.A.; Lassale, C.; Ferry, M.; Jeandel, C.; Hercberg, S.; Galan, P.; SU. VI. MAX 2 Research Group. Mediterranean diet and cognitive function: A French study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 97, 369–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, M.C.; Tangney, C.C. Dietary fat composition and dementia risk. Neurobiol. Aging 2014, 35, S59–S64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laitinen, M.; Ngandu, T.; Rovio, S.; Helkala, E.-L.; Uusitalo, U.; Viitanen, M.; Nissinen, A.; Tuomilehto, J.; Soininen, H.; Kivipelto, M. Fat intake at midlife and risk of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease: A population-based study. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2006, 22, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prince, M.; Guerchet, M.; Prina, M. The Epidemiology and Impact of DementiaCurrent State and Future Trends. WHO Thematic Briefing; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015; p. hal–03517019. [Google Scholar]

- Popkin, B.M. Relationship between shifts in food system dynamics and acceleration of the global nutrition transition. Nutr. Rev. 2017, 75, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popkin, B.M.; Ng, S.W. The nutrition transition to a stage of high obesity and noncommunicable disease prevalence dominated by ultra-processed foods is not inevitable. Obes. Rev. 2022, 23, e13366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Deng, W.; Gong, X.; Ou, J.; Yu, S.; Chen, S. Global burden of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias in adults aged 65 years and over, and health inequality related to SDI, 1990–2021: Analysis of data from GBD 2021. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, W.; Koo, F.K.; Ge, Y.; Sevastidis, J. Reevaluating the role of biological aging in dementia: A retrospective cross-sectional global analysis incorporating confounding factors. Geriatr. Nurs. 2025, 63, 643–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henneberg, M.; Piontek, J. Biological state index of human groups. Prz. Anthropol. 1975, XLI, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, W.B. Using multicountry ecological and observational studies to determine dietary risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2016, 35, 476–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Greenwood, D.C.; Risch, H.A.; Bunce, D.; Hardie, L.J.; Cade, J.E. Meat consumption and risk of incident dementia: Cohort study of 493,888 UK Biobank participants. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 114, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, M.C.; Evans, D.A.; Tangney, C.C.; Bienias, J.L.; Schneider, J.A.; Wilson, R.S.; Scherr, P.A. Dietary copper and high saturated and trans fat intakes associated with cognitive decline. Arch. Neurol. 2006, 63, 1085–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Beck, T.; Dhana, K.; Tangney, C.C.; Desai, P.; Krueger, K.; Evans, D.A.; Rajan, K.B. Dietary fats and the APOE-e4 risk allele in relation to cognitive decline: A longitudinal investigation in a biracial population sample. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2024, 28, 100211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Speedy, A.W. Global production and consumption of animal source foods. J. Nutr. 2003, 133, 4048S–4053S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, W.; Henneberg, M. Meat consumption providing a surplus energy in modern diet contributes to obesity prevalence: An ecological analysis. BMC Nutr. 2016, 2, 22. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Henneberg, M.; Rühli, F.J.; Gruber, P.; Woitek, U. Alanine transaminase individual variation is a better marker than socio-cultural factors for body mass increase in healthy males. Food Nutr. Sci. 2011, 2, 1054–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IHME. Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network. Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 (GBD 2019) Results; Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME): Seattle, WA, USA, 2020; Available online: http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool (accessed on 28 March 2021).

- The World Bank. How Does the World Bank Classify Countries? 2022. Available online: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/378834-how-does-the-world-bank-classify-countries (accessed on 24 December 2022).

- FAO. FAOSTAT-Food Balance Sheet. 2017. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/FBS (accessed on 26 November 2022).

- The World Bank. Indicators|Data. 2018. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Gaziano, T.A.; Bitton, A.; Anand, S.; Abrahams-Gessel, S.; Murphy, A. Growing epidemic of coronary heart disease in low-and middle-income countries. Curr. Probl. Cardiol. 2010, 35, 72–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, W.; Henneberg, M. Large household reduces dementia mortality: A cross-sectional data analysis of 183 populations. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0263309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The World Bank. Life Expectancy at Birth, Total (Years). 2022. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.LE00.IN (accessed on 5 April 2022).

- You, W.; Henneberg, M. Meat in modern diet, just as bad as sugar, correlates with worldwide obesity: An ecological analysis. J. Nutr. Food Sci. 2016, 6, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.; Ralston, J.; Taubert, K. Urbanization and Cardiovascular Disease–Raising Heart-Healthy Children in Today’s Cities. 2012. Available online: https://world-heart-federation.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/FinalWHFUrbanizationLoResWeb.pdf (accessed on 24 December 2022).

- Allender, S.; Foster, C.; Hutchinson, L.; Arambepola, C. Quantification of urbanization in relation to chronic diseases in developing countries: A systematic review. J. Urban Health 2008, 85, 938–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, W.; Donnelly, F. Physician care access plays a significant role in extending global and regional life expectancy. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2022, 103, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, W.; Henneberg, R.; Coventry, B.J.; Henneberg, M. Cutaneous malignant melanoma incidence is strongly associated with European depigmented skin type regardless of ambient ultraviolet radiation levels: Evidence from Worldwide population-based data. AIMS Public Health 2022, 9, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- You, W.; Rühli, F.; Eppenberger, P.; Galassi, F.M.; Diao, P.; Henneberg, M. Gluten consumption may contribute to worldwide obesity prevalence. Anthropol. Rev. 2020, 83, 327–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, W.; Henneberg, M. Relaxed natural selection contributes to global obesity increase more in males than in females due to more environmental modifications in female body mass. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0199594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Statistics Division. Composition of Macro Geographical (Continental) Regions, Geographical Sub-Regions, and Selected Economic and Other Groupings. 2013. Available online: http://unstats.un.org (accessed on 3 October 2016).

- WHO. WHO Regional Offices. 2018. Available online: http://www.who.int (accessed on 26 November 2015).

- Asia Cooperation Dialogue. Member Countries. 2018. Available online: http://www.acddialogue.com (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation. Member Economies-Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation. 2015. Available online: http://www.apec.org (accessed on 26 November 2015).

- The World Bank. Arab World|Data. 2015. Available online: http://data.worldbank.org/region/ARB (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- The United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization. UNESCO Regions-Latin America and the Caribbean. 2014. Available online: http://www.unesco.org (accessed on 26 November 2015).

- OECD. List of OECD Member Countries. 2015. Available online: http://www.oecd.org (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- South Africa Development Community. Southern African Development Community: Member States. 2015. Available online: http://www.sadc.int (accessed on 18 June 2015).

- O’Brien, R.M. A caution regarding rules of thumb for variance inflation factors. Qual. Quant. 2007, 41, 673–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivipelto, M.; Mangialasche, F.; Ngandu, T. Lifestyle interventions to prevent cognitive impairment, dementia and Alzheimer disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2018, 14, 653–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Yin, Y.; Niu, L.; Yang, X.; Du, X.; Tian, Q. Association between changes in protein intake and risk of cognitive impairment: A prospective cohort study. Nutrients 2022, 15, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, M.; Pickering, R.T.; Bradlee, M.L.; Mustafa, J.; Singer, M.R.; Moore, L.L. Animal protein intake reduces risk of functional impairment and strength loss in older adults. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 919–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunt, V.E.; LaRocca, T.J.; Bazzoni, A.E.; Sapinsley, Z.J.; Miyamoto-Ditmon, J.; Gioscia-Ryan, R.A.; Neilson, A.P.; Link, C.D.; Seals, D.R. The gut microbiome–derived metabolite trimethylamine N-oxide modulates neuroinflammation and cognitive function with aging. GeroScience 2021, 43, 377–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srikanth, V.; Maczurek, A.; Phan, T.; Steele, M.; Westcott, B.; Juskiw, D.; Münch, G. Advanced glycation endproducts and their receptor RAGE in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 2011, 32, 763–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Psaltopoulou, T.; Sergentanis, T.N.; Panagiotakos, D.B.; Sergentanis, I.N.; Kosti, R.; Scarmeas, N. Mediterranean diet, stroke, cognitive impairment, and depression: A meta-analysis. Ann. Neurol. 2013, 74, 580–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cederholm, T.; Salem Jr, N.; Palmblad, J. ω-3 fatty acids in the prevention of cognitive decline in humans. Adv. Nutr. 2013, 4, 672–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loef, M.; Walach, H. The omega-6/omega-3 ratio and dementia or cognitive decline: A systematic review on human studies and biological evidence. J. Nutr. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2013, 32, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kearney, J. Food consumption trends and drivers. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2010, 365, 2793–2807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prince, M.; Comas-Herrera, A.; Knapp, M.; Guerchet, M.; Karagiannidou, M. World Alzheimer Report 2016: Improving Healthcare for People Living with Dementia: Coverage, Quality and Costs Now and in the Future; Alzheimer’s Disease International: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Preston, S.H. The changing relation between mortality and level of economic development. Popul. Stud. 1975, 29, 231–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.-T.; Beiser, A.S.; Breteler, M.; Fratiglioni, L.; Helmer, C.; Hendrie, H.C.; Honda, H.; Ikram, M.A.; Langa, K.M.; Lobo, A. The changing prevalence and incidence of dementia over time—Current evidence. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2017, 13, 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- You, W. Colder Climates and Dementia: An Ecological Analysis of Climate-Patterned Temperature’s Influence on Neurological Health. Nurs. Health Sci. 2024, 26, e70012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- You, W.; Feng, S.; Donnelly, F. Total meat (flesh) supply may be a significant risk factor for cardiovascular diseases worldwide. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 11, 3203–3212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Meat Protein | Meat Fat | Dement Incidence | GDP PPP | Ibs | Life e(0) | Urbanization | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meat Protein | 1 | 0.648 *** | 0.737 *** | 0.673 *** | 0.642 *** | 0.515 *** | 0.648 *** |

| Meat Fat | 0.962 *** | 1 | 0.645 *** | 0.697 *** | 0.625 *** | 0.611 *** | 0.502 *** |

| Dement Incidence | 0.641 *** | 0.666 *** | 1 | 0.775 *** | 0.749 *** | 0.823 *** | 0.512 *** |

| GDP PPP | 0.732 *** | 0.703 *** | 0.777 *** | 1 | 0.783 *** | 0.854 *** | 0.680 *** |

| Ibs | 0.715 *** | 0.708 *** | 0.848 *** | 0.895 *** | 1 | 0.876 *** | 0.494 *** |

| Life e(0) | 0.648 *** | 0.636 *** | 0.829 *** | 0.880 *** | 0.930 *** | 1 | 0.552 *** |

| Urbanization | 0.549 *** | 0.513 *** | 0.525 *** | 0.720 *** | 0.630 *** | 0.640 *** | 1 |

| Country Groupings | Meat Protein → Dementia | Meat Fat → Dementia | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pearson’s r | Spearman’s rho | Pearson’s r | Spearman’s rho | N | |

| Worldwide | 0.648 *** | 0.641 *** | 0.645 *** | 0.666 *** | 184 |

| United Nations common practice | |||||

| Developed countries | 0.072 | −0.043 | −0.115 | −0.156 | 45 |

| Developing countries | 0.576 *** | 0.593 *** | 0.552 *** | 0.581 *** | 139 |

| Fisher r-to-z transformation: Developing vs. Developed | z = 3.31 *** | z = 4.11 *** | z = 4.17 *** | z = 4.65 *** | |

| World Bank income classifications | |||||

| Low Income (LI) | 0.234 | 0.233 | 0.175 | 0.221 | 28 |

| Lower Middle Income (LMI) | 0.413 ** | 0.464 *** | 0.375 ** | 0.467 *** | 49 |

| Upper Middle Income (UMI) | 0.265 * | 0.208 | 0.385 ** | 0.312 * | 52 |

| High Income (HI) | −0.139 | −0.257 * | 0.120 | −0.016 | 55 |

| Low- and middle-income (LMIC) | 0.614 *** | 0.659 *** | 0.593 *** | 0.635 *** | 129 |

| Fisher r-to-z transformation: LMIC vs. High income | z = 5.19 *** | z = 6.39 *** | z = 3.41 *** | z = 4.45 *** | |

| World Health Organization Regions | |||||

| African region | 0.509 *** | 0.453 ** | 0.438 ** | 0.411 ** | 45 |

| American region | 0.661 *** | 0.568 *** | 0.648 ** | 0.586 ** | 35 |

| Eastern Mediterranean region | 0.107 | 0.106 | 0.110 | 0.173 | 21 |

| European region | 0.550 *** | 0.330 * | 0.335 * | 0.217 | 50 |

| South-East Asian Region | 0.221 | 0.200 | 0.355 | 0.394 | 10 |

| Western Pacific Region | 0.217 | 0.142 | 0.250 | 0.227 | 23 |

| Countries grouped with various factors | |||||

| Asia Cooperation Dialogue (ACD) | 0.070 | −0.021 | 0.131 | 0.132 | 28 |

| Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) | −0.069 | −0.061 | −0.053 | −0.016 | 21 |

| Arab World | 0.722 *** | 0.687 *** | 0.743 *** | 0.730 *** | 23 |

| English as official language (EOL) | 0.724 *** | 0.732 *** | 0.697 *** | 0.743 *** | 52 |

| Latin America (LA) | 0.401 | 0.501 * | 0.466 * | 0.531 * | 18 |

| Latin America & the Caribbean (LAC) | 0.631 *** | 0.512 ** | 0.639 *** | 0.550 *** | 33 |

| Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) | −0.083 | −0.231 | −0.144 | −0.297 | 37 |

| Southern African Development Community (SADC) | 0.632 ** | 0.624 ** | 0.486 * | 0.397 | 16 |

| Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) | 0.174 | 0.170 | 0.255 | 0.256 | 26 |

| Model | Control Variables | Meat Protein (Partial r) | df | p-Value | Meat Fat (Partial r) | df | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | GDP PPP | 0.160 | 175 | 0.033 | 0.212 | 175 | 0.005 |

| 2 | GDP PPP + Ibs | 0.088 | 173 | 0.247 | 0.164 | 173 | 0.030 |

| 3 | GDP PPP + Ibs + Life e(0) | 0.159 | 172 | 0.037 | 0.217 | 172 | 0.004 |

| 4 | GDP PPP + Ibs + Life e(0) + Urbanization | 0.161 | 171 | 0.035 | 0.218 | 171 | 0.004 |

| Variable | Communalities (Meat Protein) | Communalities (Meat Fat) | Factor Loadings (Meat Protein) | Factor Loadings (Meat Fat) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meat Protein | 0.687 | – | 0.829 | – |

| Meat Fat | – | 0.634 | – | 0.796 |

| GDP PPP | 0.893 | 0.891 | 0.945 | 0.944 |

| Ibs | 0.810 | 0.805 | 0.900 | 0.897 |

| Life e(0) | 0.841 | 0.844 | 0.917 | 0.919 |

| Urbanization | 0.528 | 0.526 | 0.727 | 0.725 |

| Eigenvalue (1st component) | 3.76 | 3.70 | – | – |

| % Variance explained | 75.2% | 74.0% | – | – |

| Predictor | Enter Method: Baseline (β) | Enter Method: Protein Model (β) | Enter Method: Fat Model (β) | Stepwise: Baseline (β) | Stepwise: Protein Model (β) | Stepwise: Fat Model (β) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GDP PPP | 0.251 ** | 0.213 * | 0.196 | 0.252 ** | 0.194 * | 0.179 * |

| Ibs | 0.102 | 0.037 | 0.039 | – | – | – |

| Life e(0) | 0.523 *** | 0.530 *** | 0.526 *** | 0.820 *** 0.605 *** | 0.821 *** 0.689 *** 0.562 *** | 0.821 *** 0.683 *** 0.559 *** |

| Urbanization | −0.015 | −0.026 | −0.025 | – | – | – |

| Meat Protein | – | 0.138 * | – | – | 0.205 *** 0.143 * | – |

| Meat Fat | – | – | 0.172 ** | – | – | 0.226 *** 0.176 ** |

| R2 (Adjusted) | 0.693 (0.686) | 0.707 (0.699) | 0.714 (0.706) | 0.673 (0.671) 0.690 (0.687) | 0.675 (0.673) 0.699 (0.696) 0.707 (0.702) | 0.675 (0.673) 0.707 (0.703) 0.713 (0.708) |

| F-statistic | 98.57 *** | 82.67 *** | 85.35 *** | – | – | – |

| N | 180 | 177 | 177 | 180 | 177 | 177 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

You, W.; Feng, S. Diet and Dementia Worldwide: The Role of Meat Fat, Meat Protein, and Development Indicators. J. Dement. Alzheimer's Dis. 2025, 2, 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/jdad2040043

You W, Feng S. Diet and Dementia Worldwide: The Role of Meat Fat, Meat Protein, and Development Indicators. Journal of Dementia and Alzheimer's Disease. 2025; 2(4):43. https://doi.org/10.3390/jdad2040043

Chicago/Turabian StyleYou, Wenpeng, and Shuhuan Feng. 2025. "Diet and Dementia Worldwide: The Role of Meat Fat, Meat Protein, and Development Indicators" Journal of Dementia and Alzheimer's Disease 2, no. 4: 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/jdad2040043

APA StyleYou, W., & Feng, S. (2025). Diet and Dementia Worldwide: The Role of Meat Fat, Meat Protein, and Development Indicators. Journal of Dementia and Alzheimer's Disease, 2(4), 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/jdad2040043