Polygenic Predisposition, Multifaceted Family Protection, and Mental Health Development from Middle to Late Adulthood: A National Life Course Gene–Environment Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Nature (Genetics) and Depression

1.2. Nurture and Mental Health

1.3. Nature–Nurture Coupling Forces and Depression Development

- Assess the association between polygenic scores and trajectories of depressive symptoms across ages 51–90 years;

- Decompose the complex early protective family environment, capturing a wide spectrum of characteristics from absence of risk and family stability to positive parenting (e.g., stable family structure, non-abusive parenting, substance-free parenting, positive parent–child relationships, and parental support);

- Evaluate the impacts of these individual family factors, as well as the composite summary index of the overall family environment, on depression development;

- Investigate the gene–environment coupling roles in lifelong trajectories;

- Construct novel GxE compound measures to capture varying levels of genetic and family exposure;

- Compare whether only one favorable condition (G or E) shapes trajectories differently from middle to late adulthood.

2. Methods

2.1. Data and Sample

2.2. Depressive Symptoms

2.3. Depression Polygenic Score (PGS)

2.4. Protective Childhood Family Environment

2.5. Gene–Environment Compound Measures

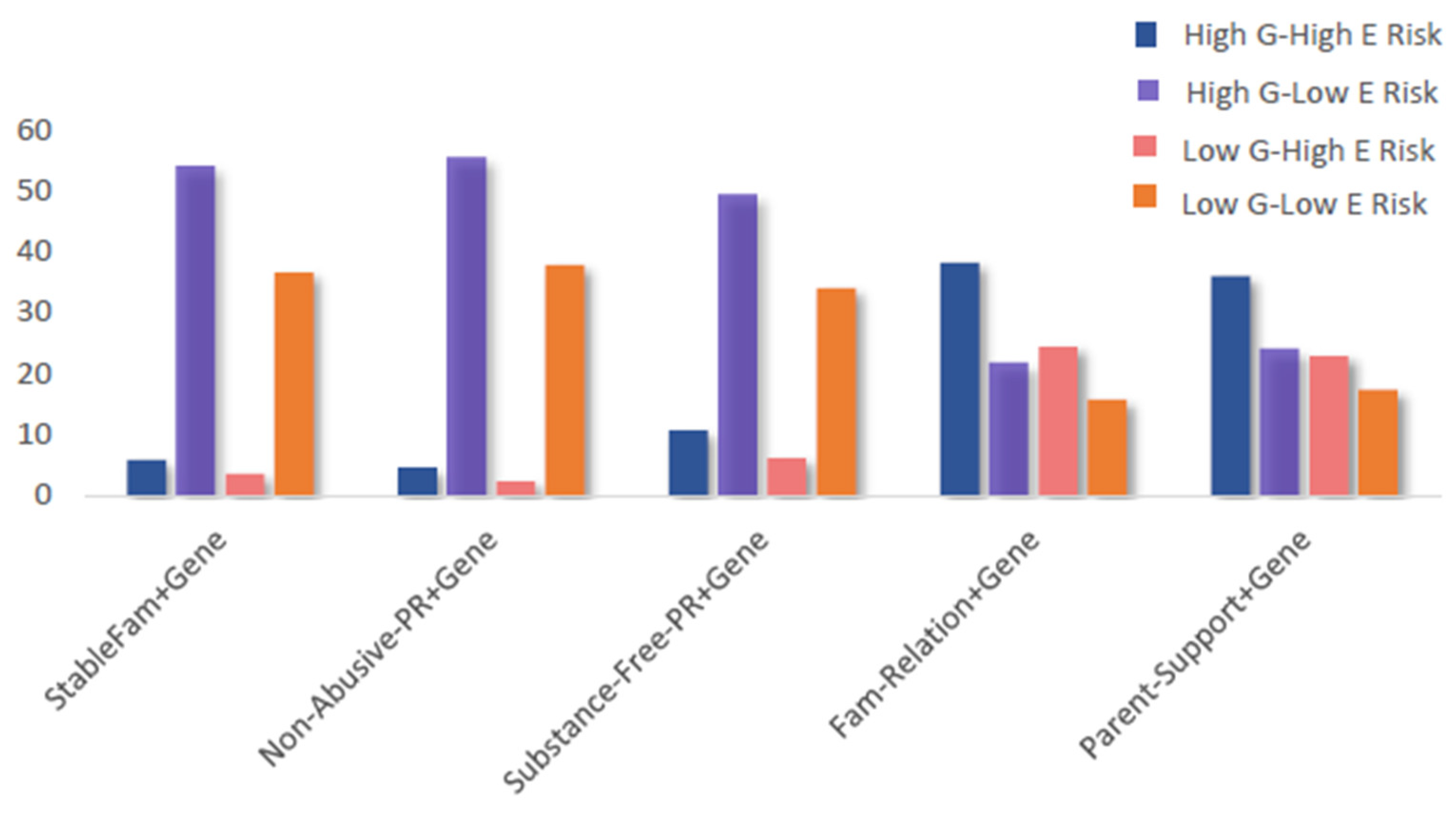

- High G Risk–High E Risk (Lowest-Level Protection): high genetic risk combined with low family protection (e.g., unstable family structure, abusive parenting, parental substance use, poor family relationships, or low parental support).

- High G Risk–Low E Risk (Medium-Level I Protection): high genetic risk combined with high family protection (e.g., stable family structure, non-abusive parenting, substance-free parenting, positive family relationships, or high parental support).

- Low G Risk–High E Risk (Medium-Level II Protection): low genetic risk combined with low family protection.

- Low G Risk–Low E Risk (Highest-Level Protection): low genetic risk combined with high family protection.

2.6. Covariates

2.7. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Results

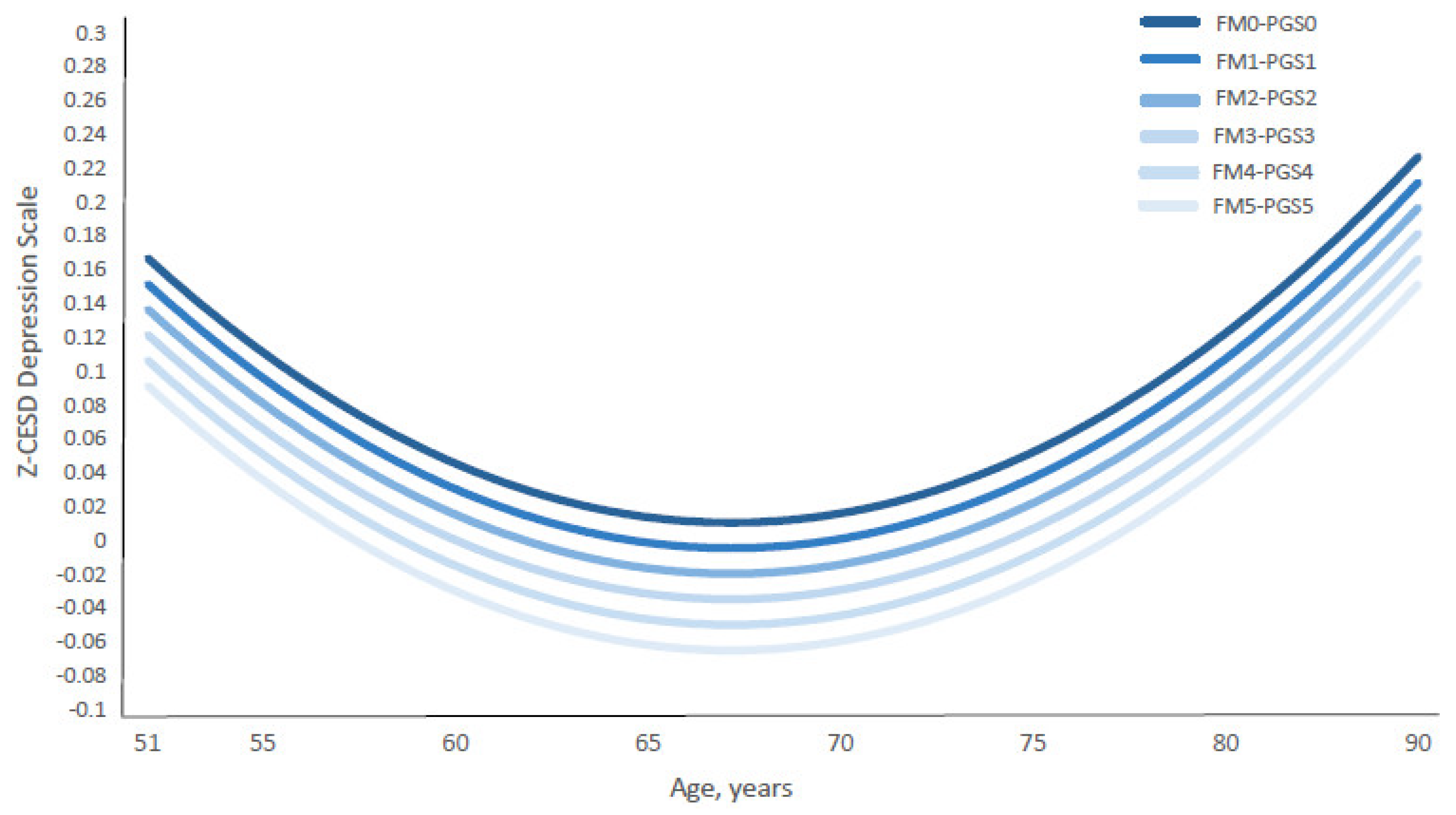

3.2. Additive G&E Exposure and CES-D Trajectories

3.3. Compound G&E Exposure and CES-D Trajectories

3.4. Genetics, Multidimensional Protective Family Environment, and CES-D Trajectories

4. Discussion

4.1. Key Findings: Gene–Environment Mechanisms

4.2. Implications for Research and Policy

4.3. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Malhi, G.S.; Mann, J.J. Depression. Lancet 2018, 392, 2299–2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization Depression. Available online: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs369/en/ (accessed on 15 December 2018).

- Bromet, E.; Andrade, L.H.; Hwang, I.; Sampson, N.A.; Alonso, J.; de Girolamo, G.; de Graaf, R.; Demyttenaere, K.; Hu, C.; Iwata, N.; et al. Cross-national epidemiology of DSM-IV major depressive episode. BMC Med. 2011, 9, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ustün, T.B.; Rehm, J.; Chatterji, S.; Saxena, S.; Trotter, R.; Room, R.; Bickenbach, J. Multiple-informant ranking of the disabling effects of different health conditions in 14 countries. WHO/NIH Joint Project CAR Study Group. Lancet 1999, 354, 111–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadhead, W.E.; Blazer, D.G.; George, L.K.; Tse, C.K. Depression, disability days, and days lost from work in a prospective epidemiologic survey. JAMA 1990, 264, 2524–2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, E.M.; Gennuso, K.P.; Ugboaja, D.C.; Remington, P.L. The epidemic of despair among white Americans: Trends in the leading causes of premature death, 1999-2015. Am. J. Public Health 2017, 107, 1541–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masters, R.K.; Tilstra, A.M.; Simon, D.H. Explaining recent mortality trends among younger and middle-aged White Americans. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2018, 47, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blazer, D.G. Depression in late life: Review and commentary. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2003, 58, 249–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiske, A.; Wetherell, J.L.; Gatz, M. Depression in older adults. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2009, 5, 363–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasin, D.S.; Goodwin, R.D.; Stinson, F.S.; Grant, B.F. Epidemiology of major depressive disorder: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcoholism and Related Conditions. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2005, 62, 1097–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sivertsen, H.; Bjørkløf, G.H.; Engedal, K.; Selbæk, G.; Helvik, A.-S. Depression and quality of life in older persons: A review. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2015, 40, 311–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cacioppo, J.T.; Cacioppo, S. Older adults reporting social isolation or loneliness show poorer cognitive function 4 years later. Evid. Based Nurs. 2014, 17, 59–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.A.; Reynolds-Iii, C.F. Late-life depression in the primary care setting: Challenges, collaborative care, and prevention. Maturitas 2014, 79, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaup, A.R.; Byers, A.L.; Falvey, C.; Simonsick, E.M.; Satterfield, S.; Ayonayon, H.N.; Smagula, S.F.; Rubin, S.M.; Yaffe, K. Trajectories of depressive symptoms in older adults and risk of dementia. JAMA Psychiatry 2016, 73, 525–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Harris, K.M. Association of positive family relationships with mental health trajectories from adolescence to midlife. JAMA Pediatr. 2019, 173, e193336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Li, Y.; Zadrozny, S.; Seifer, R.; Belger, A. Polygenic risk, childhood abuse and gene x environment interactions with depression development from middle to late adulthood: A U.S. National Life-Course Study. Prev. Med. 2024, 185, 108048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, F. The genetics of depression in childhood and adolescence. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2009, 11, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wray, N.R.; Ripke, S.; Mattheisen, M.; Trzaskowski, M.; Byrne, E.M.; Abdellaoui, A.; Adams, M.J.; Agerbo, E.; Air, T.M.; Andlauer, T.M.F.; et al. Genome-wide association analyses identify 44 risk variants and refine the genetic architecture of major depression. Nat. Genet. 2018, 50, 668–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaffee, S.R.; Price, T.S. The implications of genotype-environment correlation for establishing causal processes in psychopathology. Dev. Psychopathol. 2012, 24, 1253–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rice, F. Genetics of childhood and adolescent depression: Insights into etiological heterogeneity and challenges for future genomic research. Genome Med. 2010, 2, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lussier, A.A.; Hawrilenko, M.; Wang, M.-J.; Choi, K.W.; Cerutti, J.; Zhu, Y.; Major Depressive Disorder Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium; Dunn, E.C. Genetic susceptibility for major depressive disorder associates with trajectories of depressive symptoms across childhood and adolescence. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2021, 62, 895–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, P.F.; Neale, M.C.; Kendler, K.S. Genetic epidemiology of major depression: Review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Psychiatry 2000, 157, 1552–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendler, K.S.; Gatz, M.; Gardner, C.O.; Pedersen, N.L. A Swedish national twin study of lifetime major depression. Am. J. Psychiatry 2006, 163, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendler, K.S.; Ohlsson, H.; Lichtenstein, P.; Sundquist, J.; Sundquist, K. The genetic epidemiology of treated major depression in sweden. Am. J. Psychiatry 2018, 175, 1137–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polderman, T.J.C.; Benyamin, B.; de Leeuw, C.A.; Sullivan, P.F.; van Bochoven, A.; Visscher, P.M.; Posthuma, D. Meta-analysis of the heritability of human traits based on fifty years of twin studies. Nat. Genet. 2015, 47, 702–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, E.C.; Brown, R.C.; Dai, Y.; Rosand, J.; Nugent, N.R.; Amstadter, A.B.; Smoller, J.W. Genetic determinants of depression: Recent findings and future directions. Harv. Rev. Psychiatry 2015, 23, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyde, C.L.; Nagle, M.W.; Tian, C.; Chen, X.; Paciga, S.A.; Wendland, J.R.; Tung, J.Y.; Hinds, D.A.; Perlis, R.H.; Winslow, A.R. Identification of 15 genetic loci associated with risk of major depression in individuals of European descent. Nat. Genet. 2016, 48, 1031–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howard, D.M.; Adams, M.J.; Clarke, T.-K.; Hafferty, J.D.; Gibson, J.; Shirali, M.; Coleman, J.R.I.; Hagenaars, S.P.; Ward, J.; Wigmore, E.M.; et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis of depression identifies 102 independent variants and highlights the importance of the prefrontal brain regions. Nat. Neurosci. 2019, 22, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A. Genes, depressive symptoms, and chronic stressors: A nationally representative longitudinal study in the United States. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019, 242, 112586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, D.R.; Logue, M.W.; Wolf, E.J.; Maniates, H.; Robinson, M.E.; Hayes, J.P.; Stone, A.; Schichman, S.; McGlinchey, R.E.; Milberg, W.P.; et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder symptom severity is associated with reduced default mode network connectivity in individuals with elevated genetic risk for psychopathology. Depress. Anxiety 2017, 34, 632–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wray, N.R.; Lee, S.H.; Mehta, D.; Vinkhuyzen, A.A.E.; Dudbridge, F.; Middeldorp, C.M. Research review: Polygenic methods and their application to psychiatric traits. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2014, 55, 1068–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntosh, A.M.; Sullivan, P.F.; Lewis, C.M. Uncovering the genetic architecture of major depression. Neuron 2019, 102, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kendall, K.M.; Van Assche, E.; Andlauer, T.F.M.; Choi, K.W.; Luykx, J.J.; Schulte, E.C.; Lu, Y. The genetic basis of major depression. Psychol. Med. 2021, 51, 2217–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultheiss, D.P.; Blustein, D.L. Contributions of family relationship factors to the identity formation process. J. Couns. Dev. 1994, 73, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, J.E.; Johnson, M.K. Adolescent family context and adult identity formation. J. Fam. Issues 2009, 30, 1265–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Missildine, W.H. Your Inner Child of the Past; Simon & Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 1963; ISBN 0671747037. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association Parents and Caregivers are Essential to Children’s Healthy Development. Available online: https://www.apa.org/pi/families/resources/parents-caregivers (accessed on 19 July 2020).

- Ainsworth, M.D.S. Patterns of Attachment: A Psychological Study of the Strange Situation; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby, J. Attachment: Attachment and Loss Volume One Attachment; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby, J. The making and breaking of affectional bonds: Aetiology and psychopathology in the light of attachment theory. An expanded version of the Fiftieth Maudsley Lecture, delivered before the Royal College of Psychiatrists, 19 November 1976. Br. J. Psychiatry 1977, 130, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.E.; Stanton, A.L. Coping resources, coping processes, and mental health. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2007, 3, 377–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmerman, M.A.; Stoddard, S.A.; Eisman, A.B.; Caldwell, C.H.; Aiyer, S.M.; Miller, A. Adolescent resilience: Promotive factors that inform prevention. Child Dev. Perspect. 2013, 7, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Repetti, R.L.; Taylor, S.E.; Seeman, T.E. Risky families: Family social environments and the mental and physical health of offspring. Psychol. Bull. 2002, 128, 330–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkman, L.F.; Glass, T.; Brissette, I.; Seeman, T.E. From social integration to health: Durkheim in the new millennium. Soc. Sci. Med. 2000, 51, 843–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hostinar, C.E.; Gunnar, M.R. Social Support Can Buffer against Stress and Shape Brain Activity. AJOB Neurosci. 2015, 6, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoits, P.A. Mechanisms linking social ties and support to physical and mental health. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2011, 52, 145–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P. Inner child of the past: Long-term protective role of childhood relationships with mothers and fathers and maternal support for mental health in middle and late adulthood. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2022, 57, 1399–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heim, C.; Binder, E.B. Current research trends in early life stress and depression: Review of human studies on sensitive periods, gene-environment interactions, and epigenetics. Exp. Neurol. 2012, 233, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eaves, L.J. Genotype x Environment interaction in psychopathology: Fact or artifact? Twin Res. Hum. Genet. 2006, 9, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, L.E.; Keller, M.C. A critical review of the first 10 years of candidate gene-by-environment interaction research in psychiatry. Am. J. Psychiatry 2011, 168, 1041–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.J.; Berk, M.S.; Lee, S.S. Differential susceptibility in longitudinal models of gene-environment interaction for adolescent depression. Dev. Psychopathol. 2013, 25, 991–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyrot, W.J.; Milaneschi, Y.; Abdellaoui, A.; Sullivan, P.F.; Hottenga, J.J.; Boomsma, D.I.; Penninx, B.W.J.H. Effect of polygenic risk scores on depression in childhood trauma. Br. J. Psychiatry 2014, 205, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musliner, K.L.; Seifuddin, F.; Judy, J.A.; Pirooznia, M.; Goes, F.S.; Zandi, P.P. Polygenic risk, stressful life events and depressive symptoms in older adults: A polygenic score analysis. Psychol. Med. 2015, 45, 1709–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullins, N.; Power, R.A.; Fisher, H.L.; Hanscombe, K.B.; Euesden, J.; Iniesta, R.; Levinson, D.F.; Weissman, M.M.; Potash, J.B.; Shi, J.; et al. Polygenic interactions with environmental adversity in the aetiology of major depressive disorder. Psychol. Med. 2016, 46, 759–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klengel, T.; Binder, E.B. Epigenetics of Stress-Related Psychiatric Disorders and Gene × Environment Interactions. Neuron 2015, 86, 1343–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, C.; McLanahan, S.; Hobcraft, J.; Brooks-Gunn, J.; Garfinkel, I.; Notterman, D. Family Structure Instability, Genetic Sensitivity, and Child Well-Being. Am. J. Sociol. 2015, 120, 1195–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabe, H.J.; Schwahn, C.; Appel, K.; Mahler, J.; Schulz, A.; Spitzer, C.; Fenske, K.; Barnow, S.; Lucht, M.; Freyberger, H.J.; et al. Childhood maltreatment, the corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor gene and adult depression in the general population. Am. J. Med. Genet. B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2010, 153B, 1483–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, R.G.; Binder, E.B.; Epstein, M.P.; Tang, Y.; Nair, H.P.; Liu, W.; Gillespie, C.F.; Berg, T.; Evces, M.; Newport, D.J.; et al. Influence of child abuse on adult depression: Moderation by the corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor gene. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2008, 65, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polanczyk, G.; Caspi, A.; Williams, B.; Price, T.S.; Danese, A.; Sugden, K.; Uher, R.; Poulton, R.; Moffitt, T.E. Protective effect of CRHR1 gene variants on the development of adult depression following childhood maltreatment: Replication and extension. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2009, 66, 978–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatt, J.M.; Nemeroff, C.B.; Dobson-Stone, C.; Paul, R.H.; Bryant, R.A.; Schofield, P.R.; Gordon, E.; Kemp, A.H.; Williams, L.M. Interactions between BDNF Val66Met polymorphism and early life stress predict brain and arousal pathways to syndromal depression and anxiety. Mol. Psychiatry 2009, 14, 681–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, P.; Brückl, T.; Pfister, H.; Lieb, R.; Wittchen, H.U.; Holsboer, F.; Ising, M.; Binder, E.B.; Uhr, M.; Nocon, A. The interplay of variations in the FKBP5 gene and adverse life events in predicting the first onset of depression during a ten-year follow-up. Pharmacopsychiatry 2009, 42, A189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bet, P.M.; Penninx, B.W.J.H.; Bochdanovits, Z.; Uitterlinden, A.G.; Beekman, A.T.F.; van Schoor, N.M.; Deeg, D.J.H.; Hoogendijk, W.J.G. Glucocorticoid receptor gene polymorphisms and childhood adversity are associated with depression: New evidence for a gene-environment interaction. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2009, 150B, 660–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, P.; Brückl, T.; Nocon, A.; Pfister, H.; Binder, E.B.; Uhr, M.; Lieb, R.; Moffitt, T.E.; Caspi, A.; Holsboer, F.; et al. Interaction of FKBP5 gene variants and adverse life events in predicting depression onset: Results from a 10-year prospective community study. Am. J. Psychiatry 2011, 168, 1107–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwong, A.S.F.; López-López, J.A.; Hammerton, G.; Manley, D.; Timpson, N.J.; Leckie, G.; Pearson, R.M. Genetic and environmental risk factors associated with trajectories of depression symptoms from adolescence to young adulthood. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e196587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warrier, V.; Kwong, A.S.F.; Luo, M.; Dalvie, S.; Croft, J.; Sallis, H.M.; Baldwin, J.; Munafò, M.R.; Nievergelt, C.M.; Grant, A.J.; et al. Gene-environment correlations and causal effects of childhood maltreatment on physical and mental health: A genetically informed approach. Lancet Psychiatry 2021, 8, 373–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwong, A.S.F.; Morris, T.T.; Pearson, R.M.; Timpson, N.J.; Rice, F.; Stergiakouli, E.; Tilling, K. Polygenic risk for depression, anxiety and neuroticism are associated with the severity and rate of change in depressive symptoms across adolescence. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2021, 62, 1462–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elder, G.H. The life course as developmental theory. Child Dev. 1998, 69, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halfon, N.; Forrest, C.B.; Lerner, R.M.; Faustman, E.M. (Eds.) Handbook of life Course Health Development; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; ISBN 9783319471419. [Google Scholar]

- Clayton, D.; McKeigue, P.M. Epidemiological methods for studying genes and environmental factors in complex diseases. Lancet 2001, 358, 1356–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnega, A.; Faul, J.D.; Ofstedal, M.B.; Langa, K.M.; Phillips, J.W.R.; Weir, D.R. Cohort profile: The health and retirement study (HRS). Int. J. Epidemiol. 2014, 43, 576–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juster, F.T.; Suzman, R. An overview of the health and retirement study. J. Hum. Resour. 1995, 30, S7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, G.G.; Ryan, L.H. Overview of the health and retirement study and introduction to the special issue. Work, Aging and Retire. 2018, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- HRS 2020 HRS COVID-19 Project|Health and Retirement Study. Available online: https://hrsdata.isr.umich.edu/data-products/2020-hrs-covid-19-project (accessed on 15 January 2022).

- HRS. CIDR Health Retirement Study Imputation Report—1000 Genomes Project Reference Panel: Summary and Recommendations for dbGaP Users; University of Michigan: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Highland, H.M.; Avery, C.L.; Duan, Q.; Li, Y.; Harris, K.M. Quality Control Analysis of Add Health GWAS Data; Carolina Population Center, University of North Carolina: Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, A.R.; Gignoux, C.R.; Walters, R.K.; Wojcik, G.L.; Neale, B.M.; Gravel, S.; Daly, M.J.; Bustamante, C.D.; Kenny, E.E. Human Demographic History Impacts Genetic Risk Prediction across Diverse Populations. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2017, 100, 635–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.J.; Wedow, R.; Okbay, A.; Kong, E.; Maghzian, O.; Zacher, M.; Nguyen-Viet, T.A.; Bowers, P.; Sidorenko, J.; Karlsson Linnér, R.; et al. Gene discovery and polygenic prediction from a genome-wide association study of educational attainment in 1.1 million individuals. Nat. Genet. 2018, 50, 1112–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson Linnér, R.; Biroli, P.; Kong, E.; Meddens, S.F.W.; Wedow, R.; Fontana, M.A.; Lebreton, M.; Tino, S.P.; Abdellaoui, A.; Hammerschlag, A.R.; et al. Genome-wide association analyses of risk tolerance and risky behaviors in over 1 million individuals identify hundreds of loci and shared genetic influences. Nat. Genet. 2019, 51, 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herd, P.; Freese, J.; Sicinski, K.; Domingue, B.W.; Mullan Harris, K.; Wei, C.; Hauser, R.M. Genes, gender inequality, and educational attainment. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2019, 84, 1069–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, K.M.; Halpern, C.T.; Whitsel, E.A.; Hussey, J.M.; Killeya-Jones, L.A.; Tabor, J.; Dean, S.C. Cohort profile: The national longitudinal study of adolescent to adult health (add health). Int. J. Epidemiol. 2019, 48, 1415-1415k. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karim, J.; Weisz, R.; Bibi, Z.; Rehman, S. Validation of the Eight-Item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) Among Older Adults. Curr. Psychol. 2015, 34, 681–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffick, D.E. Documentation of Affective Functioning Measures in the Health and Retirement Study; University of Michigan: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Euesden, J.; Lewis, C.M.; O’Reilly, P.F. PRSice: Polygenic Risk Score software. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 1466–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halldorsdottir, T.; Piechaczek, C.; Soares de Matos, A.P.; Czamara, D.; Pehl, V.; Wagenbuechler, P.; Feldmann, L.; Quickenstedt-Reinhardt, P.; Allgaier, A.-K.; Freisleder, F.J.; et al. Polygenic risk: Predicting depression outcomes in clinical and epidemiological cohorts of youths. Am. J. Psychiatry 2019, 176, 615–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, K.M.; Chen, P. The acculturation gap of parent–child relationships in immigrant families: A national study. Fam. Relat. 2022, 72, 1748–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assari, S.; Caldwell, C.H. Neighborhood safety and major depressive disorder in a national sample of black youth; gender by ethnic differences. Children 2017, 4, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrissey, K.; Kinderman, P. The impact of financial hardship in childhood on depression and anxiety in adult life: Testing the accumulation, critical period and social mobility hypotheses. SSM Popul. Health 2020, 11, 100592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Gao, F.; Kang, Z.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, J.; Li, J.; Yan, J.; Wang, J.; Liu, H.; Wu, Q.; et al. Perceived academic stress and depression: The mediation role of mobile phone addiction and sleep quality. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 760387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raudenbush, S.W.; Bryk, A.S. Hierarchical Linear Models: Applications and Data Analysis Methods, 2nd ed.; Advanced quantitative techniques in the social sciences; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002; p. 512. ISBN 9780761919049. [Google Scholar]

- Rabe-Hesketh, S.; Skrondal, A. Multilevel and Longitudinal Modeling Using Stata, 3rd ed.; Stata Press: College Station, TX, USA, 2012; ISBN 978-1-59718-103-7. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan, S.C.; Duncan, T.E.; Hops, H. Analysis of longitudinal data within accelerated longitudinal designs. Psychol. Methods 1996, 1, 236–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McArdle, J.J.; Hamagami, F. Modeling incomplete longitudinal and cross-sectional data using latent growth structural models. Exp. Aging Res. 1992, 18, 145–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singer, J.D.; Willett, J.B. Applied Longitudinal Data Analysis: Modeling Change and Event Occurrence; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Guo, G. Lifetime socioeconomic status, historical context, and genetic inheritance in shaping body mass in middle and late adulthood. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2015, 80, 705–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingue, B.W.; Belsky, D.W.; Harrati, A.; Conley, D.; Weir, D.R.; Boardman, J.D. Mortality selection in a genetic sample and implications for association studies. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2017, 46, 1285–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belsky, J.; Jonassaint, C.; Pluess, M.; Stanton, M.; Brummett, B.; Williams, R. Vulnerability genes or plasticity genes? Mol. Psychiatry 2009, 14, 746–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, G.; Azhari, A.; Borelli, J.L. Gene × environment interaction in developmental disorders: Where do we stand and what’s next? Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinde, R.A. Attachment: Some Conceptual and Biological Issues. In The Place of Attachment in Human Behavior; Parkes, C.M., Stevenson-Hinde, J., Eds.; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Armsden, G.C.; Greenberg, M.T. The inventory of parent and peer attachment: Individual differences and their relationship to psychological well-being in adolescence. J. Youth Adolesc. 1987, 16, 427–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corr, R.; Glier, S.; Bizzell, J.; Pelletier-Baldelli, A.; Campbell, A.; Killian-Farrell, C.; Belger, A. Stress-related hippocampus activation mediates the association between polyvictimization and trait anxiety in adolescents. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2022, 17, 767–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corr, R.; Pelletier-Baldelli, A.; Glier, S.; Bizzell, J.; Campbell, A.; Belger, A. Neural mechanisms of acute stress and trait anxiety in adolescents. Neuroimage Clin. 2021, 29, 102543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thoits, P.A. Social support as coping assistance. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1986, 54, 416–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olstad, R.; Sexton, H.; Søgaard, A.J. The Finnmark Study. A prospective population study of the social support buffer hypothesis, specific stressors and mental distress. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2001, 36, 582–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, M.B.H.; Pilkington, P.D.; Ryan, S.M.; Jorm, A.F. Parental factors associated with depression and anxiety in young people: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2014, 156, 8–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallers, M.H.; Charles, S.T.; Neupert, S.D.; Almeida, D.M. Perceptions of childhood relationships with mother and father: Daily emotional and stressor experiences in adulthood. Dev. Psychol. 2010, 46, 1651–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, D.S. Developing Genome: An Introduction to Behavioral Epigenetics; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Szyf, M. The epigenetics of perinatal stress. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2019, 21, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weaver, I.C.G.; Cervoni, N.; Champagne, F.A.; D’Alessio, A.C.; Sharma, S.; Seckl, J.R.; Dymov, S.; Szyf, M.; Meaney, M.J. Epigenetic programming by maternal behavior. Nat. Neurosci. 2004, 7, 847–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishimi, K.; Bürgin, D.; O’Donovan, A. Psychological resilience to lifetime trauma and risk for cardiometabolic disease and mortality in older adults: A longitudinal cohort study. J. Psychosom. Res. 2023, 175, 111539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Jie, W.; Huang, X.; Yang, F.; Qian, Y.; Yang, T.; Dai, M. Association of psychological resilience with all-cause and cause-specific mortality in older adults: A cohort study. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keller, M.C. Gene × environment interaction studies have not properly controlled for potential confounders: The problem and the (simple) solution. Biol. Psychiatry 2014, 75, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, K.M.; Yaffe, K.; Covinsky, K.E. Cognitive impairment, depressive symptoms, and functional decline in older people. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2002, 50, 1045–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.P. Reconstructing childhood health histories. Demography 2009, 46, 387–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, P.H. Of Human Bonding: Parent-Child Relations Across the Life Course; Rossi, A.S., Ed.; Aldine Transaction: Chicago, IL, USA, 1990; ISBN 9780202367552. [Google Scholar]

| Characteristics: N (%) | HRS (N = 4817) |

|---|---|

| CES-D scale at baseline, mean (SD) | 0.77 (1.48) (range 0–8) |

| Biological sex: male | 1970 (40.90) |

| Biological sex: female | 2847 (59.10) |

| Age at baseline, mean (SD) | 58.51 (4.76) (range 53–79) |

| Polygenic score, mean (SD) | −0.000048 (0.0000099) |

| Standardized PGS score, range | −3.78 to 3.66 |

| Low polygenic risk for depression (PGS) (yes) | 1930 (40.00) |

| Protective Family Factors | |

| Stable family with married parents (SFMP)—binary (yes) | 4366 (90.64) |

| Non-abusive parenting (NABS)—binary (yes) | 4488 (93.17) |

| Substance-free parenting (SBFR)—binary (yes) | 4008 (83.21) |

| Parent–child relationships scale, mean (SD) | 4.06 (1.00) (range 1–5) |

| Positive parent–child relationship (PCRL)—binary (yes) | 1808 (37.53) |

| Parental support scale (PRSP), mean (SD) | 3.45 (0.69) (range 1–4) |

| High parental support (PRSP)—binary (yes) | 1989 (41.29) |

| Gene–Environment Composite Measures | |

| Composite PGS–Stable-Family Measure | |

| High G–high E risk (lowest-level protection) | 282 (5.854) |

| High G–low E risk (medium-level I protection) | 2605 (54.08) |

| Low G–high E risk (medium-level II protection) | 169 (3.508) |

| Low G–low E risk (highest-level protection) | 1761 (36.56) |

| Composite PGS–Non-Abusive-Parenting Measure | |

| High G–high E risk (lowest-level protection) | 217 (4.505) |

| High G–low E risk (medium-level I protection) | 2670 (55.43) |

| Low G–high E risk (medium-level II protection) | 112 (2.325) |

| Low G–low E risk (highest-level protection) | 1818 (37.74) |

| Composite PGS–Substance-Free-Parenting Measure | |

| High G–high E risk (lowest-level protection) | 513 (10.65) |

| High G–low E risk (medium-level I protection) | 2374 (49.28) |

| Low G–high E risk (medium-level II protection) | 296 (6.145) |

| Low G–low E risk (highest-level protection) | 1634 (33.92) |

| Composite PGS–Family-Relationships Measure | |

| High G–high E risk (lowest-level protection) | 1836 (38.12) |

| High G–low E risk (medium-level I protection) | 1051 (21.82) |

| Low G–high E risk (medium-level II protection) | 1173 (24.35) |

| Low G–low E risk (highest-level protection) | 757 (15.72) |

| Composite PGS–Parental-Support Measure | |

| High G–high E risk (lowest-level protection) | 1731 (35.94) |

| High G–low E risk (medium-level I protection) | 1156 (24.00) |

| Low G–high E risk (medium-level II protection) | 1097 (22.77) |

| Low G–low E risk (highest-level protection) | 833 (17.29) |

| Childhood Family Environment Index (FMIDX) | |

| Mean (s.d.) | 3.46 (1.14) |

| 0 (Standardized (Z)-FMIDX = −3.0354) | 42 (0.872) |

| 1 (Z-FMIDX = −2.1577) | 183 (3.799) |

| 2 (Z-FMIDX = −1.27999) | 640 (13.29) |

| 3 (Z-FMIDX = −0.4023) | 1699 (35.27) |

| 4 (Z-FMIDX = 0.4754) | 1166 (24.21) |

| 5 (Z-FMIDX = 1.3531) | 1087 (22.57) |

| Categorized Childhood Family Environment | |

| Low-level protective environment (FMIDX = 0 or 1) | 225 (4.671) |

| Medium-level protective environment (FMIDX = 2 or 3) | 2339 (48.56) |

| High-level protective environment (FMIDX = 4 or 5) | 2253 (46.77) |

| Birth cohort | |

| ≤1930 | 469 (9.736) |

| 1931–1940 | 1639 (34.03) |

| 1941–1950 | 1699 (35.27) |

| 1951–1960 | 1010 (20.97) |

| General good health during childhood | 2777 (57.65) (excellent) |

| 1212 (25.16) (very good) | |

| 605 (12.56) (good) | |

| 182 (3.778) (fair) | |

| 41 (0.851) (poor) | |

| Educational Level | |

| <HS | 309 (6.415) |

| GED/HS | 2670 (55.43) |

| Some college | 305 (6.332) |

| ≥4yr college | 1533 (31.82) |

| No family financial difficulty during childhood | 3441 (71.43) |

| Not repeated school | 4233 (87.88) |

| Parental education | |

| No high school degree | 3617 (75.09) |

| High school diploma or higher degrees | 1200 (24.91) |

| Models | Variables | Beta (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Model 1.1—PGS and Stable Family with Married Parents (SFMP) | Z-PGS | 0.076 *** (0.056, 0.096) |

| SFMP | −0.045 (−0.11, 0.023) | |

| Model 1.2—Composite PGS-SFMP Measure | Binary PGS and SFMP | |

| High G–high E risk (lowest-level protection) | Reference | |

| High G–low E risk (medium-level I protection) | −0.034 (−0.12, 0.052) | |

| Low G–high E risk (medium-level II protection) | −0.089 (−0.22, 0.043) | |

| Low G–low E risk (highest-level protection) | −0.17 *** (−0.26,−0.080) | |

| Model 2.1—PGS and Non-Abusive Parenting (NABS) | Z-PGS | 0.074 *** (0.054, 0.094) |

| NABS | −0.26 *** (−0.34, −0.18) | |

| Model 2.2—Composite PGS-NABS Measure | Binary PGS and NABS | |

| High G–high E risk (lowest-level protection) | Reference | |

| High G–low E risk (medium-level I protection) | −0.31 *** (−0.41, −0.22) | |

| Low G–high E risk (medium-level II protection) | −0.26 ** (−0.42, −0.11) | |

| Low G–low E risk (highest-level protection) | −0.43 *** (−0.53, −0.33) | |

| Model 3.1—PGS and Substance-Free Parenting (SBFR) | Z-PGS | 0.075 *** (0.055, 0.095) |

| SBFR | −0.098 *** (−0.15, −0.045) | |

| Model 3.2—Composite PGS-SBFR Measure | Binary PGS and SBFR | |

| High G–high E risk (lowest-level protection) | Reference | |

| High G–low E risk (medium-level I protection) | −0.12 *** (−0.19, −0.055) | |

| Low G–high E risk (medium-level II protection) | −0.17 *** (−0.27, −0.075) | |

| Low G–low E risk (highest-level protection) | −0.24 *** (−0.31, −0.17) | |

| Model 4.1—PGS and Positive Family Relationships (PCRL) | Z-PGS | 0.075 *** (0.055, 0.095) |

| PCRL | −0.12 *** (−0.16, −0.083) | |

| Model 4.2—Composite PGS-PCRL Measure | Binary PGS and PCRL | |

| High G–high E risk (lowest-level protection) | Reference | |

| High G–low E risk (medium-level I protection) | −0.15 *** (−0.20, −0.092) | |

| Low G–high E risk (medium-level II protection) | −0.15 *** (−0.20, −0.094) | |

| Low G–low E risk (highest-level protection) | −0.24 *** (−0.30, −0.18) | |

| Model 5.1—PGS and Parent Support (PRSP) | Z-PGS | 0.074 *** (0.055, 0.094) |

| PRSP | −0.14 *** (−0.18, −0.10) | |

| Model 5.2—Composite PGS-PRSP Measure | Binary PGS and PRSP | |

| High G–high E risk (lowest-level protection) | Reference | |

| High G–low E risk (medium-level I protection) | −0.17 *** (−0.23, −0.12) | |

| Low G–high E risk (medium-level II protection) | −0.16 *** (−0.21, −0.10) | |

| Low G–low E risk (highest-level protection) | −0.26 *** (−0.32, −0.20) |

| Models | Variables/Statistic | Beta (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Model 1—Z-PGS and FMIDX | Z-PGS | 0.072 *** (0.052, 0.091) |

| FMIDX | −0.078 *** (−0.096, −0.060) | |

| Model 2—Z-PGS and Z-FMIDX | Z-PGS | 0.072 *** (0.052, 0.091) |

| Z-FMIDX | −0.089 *** (−0.11, −0.069) | |

| Model 3—Z-PGS and Z-FMIDX | Z-PGS | 0.073 *** (0.053–0.093) |

| Low family protection (FMIDX = 0–1) | Reference | |

| Medium family protection (FMIDX = 2–3) | −0.078 (−0.17, 0.017) | |

| High family protection (FMIDX = 4–5) | −0.25 *** (−0.34, −0.15) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, P.; Li, Y. Polygenic Predisposition, Multifaceted Family Protection, and Mental Health Development from Middle to Late Adulthood: A National Life Course Gene–Environment Study. Populations 2025, 1, 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/populations1040022

Chen P, Li Y. Polygenic Predisposition, Multifaceted Family Protection, and Mental Health Development from Middle to Late Adulthood: A National Life Course Gene–Environment Study. Populations. 2025; 1(4):22. https://doi.org/10.3390/populations1040022

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Ping, and Yi Li. 2025. "Polygenic Predisposition, Multifaceted Family Protection, and Mental Health Development from Middle to Late Adulthood: A National Life Course Gene–Environment Study" Populations 1, no. 4: 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/populations1040022

APA StyleChen, P., & Li, Y. (2025). Polygenic Predisposition, Multifaceted Family Protection, and Mental Health Development from Middle to Late Adulthood: A National Life Course Gene–Environment Study. Populations, 1(4), 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/populations1040022