Locus of Control and Utilization of Skilled Birth Care in Nigeria: The Mediating Influence of Neuroticism

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Locus of Control and Health Outcomes

1.2. Neuroticism and Health Outcomes

1.3. Locus of Control, Neuroticism, and Health Outcomes

2. Materials and Methods

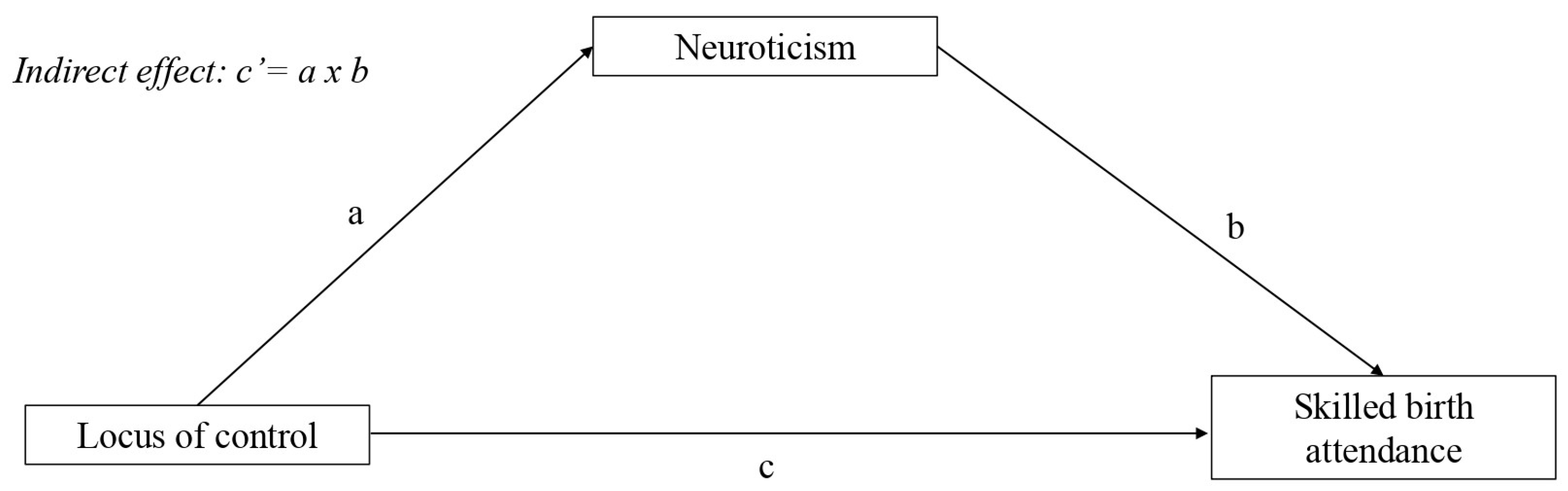

2.1. Empirical Analysis

2.2. Data

2.3. Measurement

2.3.1. Outcome Variable (Skilled Birth Attendant)

2.3.2. Explanatory Variable (Locus of Control)

- (a)

- I have little control over the things that happen to me.

- (b)

- There is really no way I can solve some of the problems I have.

- (c)

- There is little I can do to change many of the important things in my life.

- (d)

- I often feel helpless in dealing with the problems of life.

- (e)

- Sometimes, I feel that I am being pushed around in life.

- (f)

- What happens to me in the future mostly depends on me.

- (g)

- I can do just about anything I really set my mind to do.

2.3.3. Mediating Variable (Neuroticism)

- (a)

- I see myself as someone who is relaxed and handles stress well.

- (b)

- I see myself as someone who does not easily get upset and is emotionally stable.

- (c)

- I see myself as someone who gets nervous easily.

- (d)

- I see myself as someone who worries a lot.

- (e)

- I see myself as someone who is easily distracted.

2.3.4. Control Variables

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

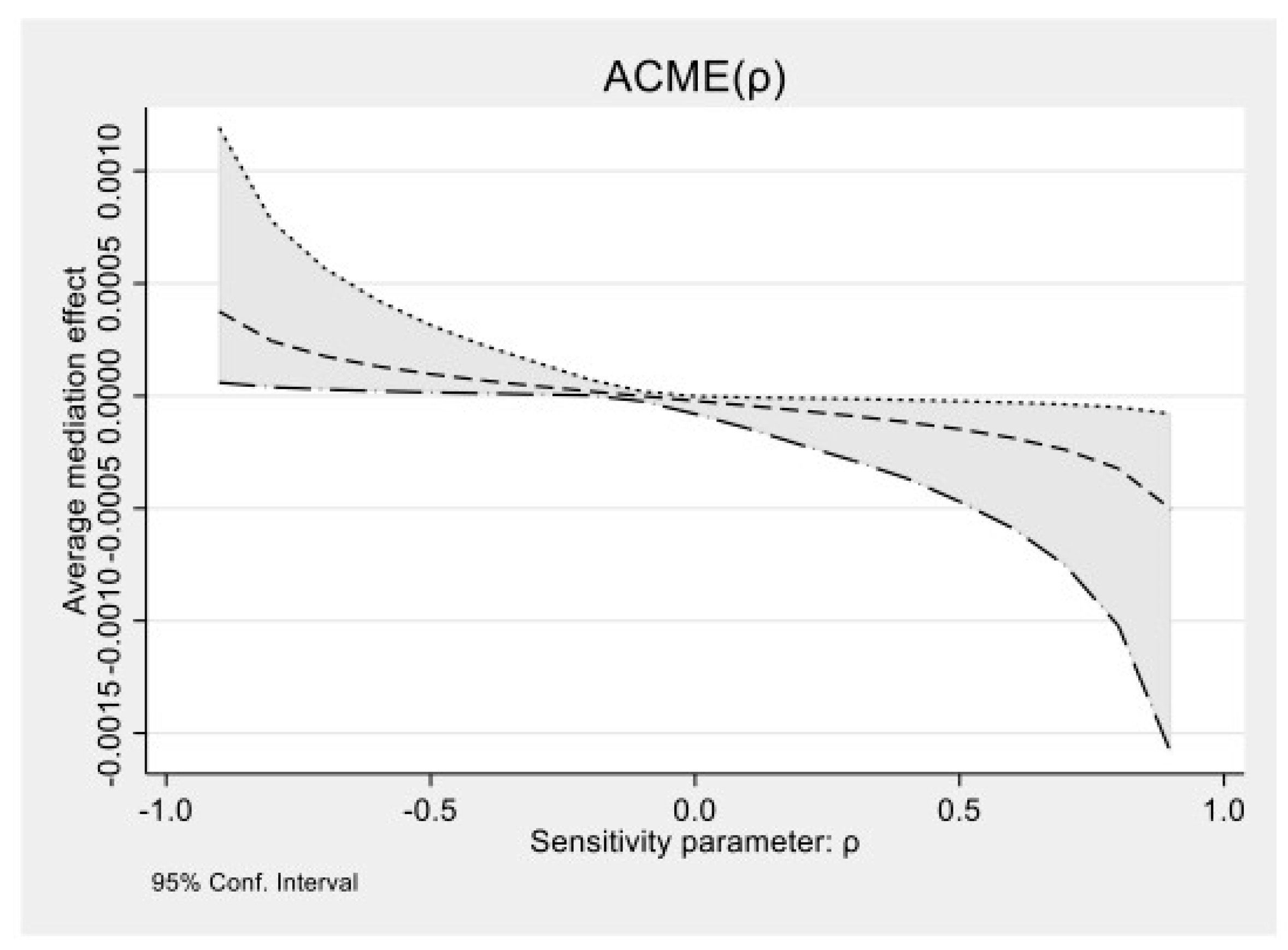

Sensitivity Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications for Policy

4.2. Limitations and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variables | Sample Size (n = 1359) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total N = 1359 N (%) | No SBA N = 166 N (%) | SBA N = 1193 N (%) | p-Value | |

| Locus of control | 0.010 | |||

| External LOC | 1205 (88.67) | 157 (11.55) | 1048 (77.12) | |

| Internal LOC | 154 (1.31) | 9 (0.66) | 145 (10.65) | |

| Age | 0.087 | |||

| 15–24 | 231 (17.1) | 24 (1.8) | 207 (15.3) | |

| 25–34 | 563 (41.5) | 75 (5.5) | 488 (36.0) | |

| 35–44 | 401 (29.6) | 55 (4.1) | 346 (25.5) | |

| >44 | 161 (11.9) | 11 (0.8) | 150 (11.1) | |

| Education | 0.000 | |||

| No education | 170 (12.5) | 40 (2.9) | 130 (9.6) | |

| Primary | 570 (41.9) | 75 (5.5) | 495 (36.4) | |

| Secondary | 557 (41.0) | 46 (3.4) | 511 (37.6) | |

| Higher | 62 (4.6) | 5 (0.4) | 57 (4.2) | |

| Cohabitation status | 0.000 | |||

| Cohabiting | 743 (54.6) | 116 (8.5) | 627 (46.1) | |

| Not cohabiting | 616 (45.4) | 50 (3.7) | 566 (41.7) | |

| Occupation | 0.729 | |||

| Not working | 305 (22.5) | 39 (2.9) | 266 (19.6) | |

| Working | 1054 (77.6) | 127 (9.4) | 927 (68.2) | |

| Religion | 0.108 | |||

| Christianity | 1301 (95.7) | 155 (11.4) | 1146 (84.3) | |

| Islam | 39 (2.9) | 9 (0.7) | 30 (2.2) | |

| Others | 19 (1.5) | 2 (0.2) | 17 (1.3) | |

| Number of children | 0.843 | |||

| 1 | 807 (70.8) | 79 (6.9) | 728 (63.9) | |

| 2 | 301 (26.4) | 30 (2.6) | 271 (23.8) | |

| 3 | 30 (2.7) | 2 (0.2) | 28 (2.5) | |

| Partner’s age | 0.133 | |||

| 18–37 | 470 (34.6) | 52 (3.8) | 418 (30.8) | |

| 38–57 | 796 (58.6) | 105 (7.7) | 691 (50.9) | |

| 58–77 | 69 (5.1) | 4 (0.3) | 65 (4.8) | |

| >77 | 24 (1.8) | 5 (0.4) | 19 (1.4) | |

| Partner’s education | 0.000 | |||

| No education | 202 (14.9) | 44 (3.3) | 158 (11.6) | |

| Primary | 369 (27.1) | 45 (3.3) | 324 (23.8) | |

| Secondary | 615 (45.2) | 64 (4.7) | 551 (40.5) | |

| Higher | 173 (12.7) | 13 (0.9) | 160 (11.8) | |

| Partner’s occupation | 0.653 | |||

| Not working | 221 (16.2) | 29 (2.1) | 192 (14.1) | |

| Working | 1138 (83.8) | 137 (10.1) | 1001 (73.7) | |

| Healthcare decision | 0.247 | |||

| Self | 186 (13.7) | 28 (2.1) | 158 (11.6) | |

| Partner | 712 (52.4) | 77 (5.7) | 635 (46.7) | |

| Both | 455 (33.4) | 61 (4.5) | 394 (28.9) | |

| Others | 6 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (0.4) | |

References

- World Health Organization. Research on Reproductive Health at WHO: Biennial Report 2000–2001; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global Action for Skilled Attendants for Pregnant Women. Appendix 2; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- National Population Commission (NPC) [Nigeria]; ICF. Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey 2018; NPC: Abuja, Nigeria; ICF: Rockville, MD, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Trends in Maternal Mortality Estimates 2000 to 2023: Estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group and UNDESA/Population Division; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Integrated Management of Pregnancy and Childbirth: Standards for Maternal And Neonatal Care; WHO Department of Making Pregnancy Safer: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Izugbara, C.O.; Wekesah, F.M.; Adedini, S.A. Maternal Health in Nigeria: A Situation Update; African Population and Health Research Center (APHRC): Nairobi, Kenya, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World Mortality Report 2013. CD-ROM Edition, Datasets in Excel Format and Interactive Charts (POP/DB/MORT/2013); United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ntoimo, L.F.; Okonofua, F.E.; Igboin, B.; Ekwo, C.; Imongan, W.; Yaya, S. Why rural women do not use primary health centres for pregnancy care: Evidence from a qualitative study in Nigeria. BMC Preg. Childbirth 2019, 19, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aikpitanyi, J.; Okonofua, F.; Ntoimo, L.; Tubeuf, S. Demand-side barriers to access and utilization of skilled birth care in lower and lower-middle-income countries: A scoping review of evidence. Afr. J. Reprod. Health 2022, 26, 30–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConnell, M.; Rothschild, C.W.; Ettenger, A.; Muigai, F.; Cohen, J. Free contraception and behavioural nudges in the postpartum period: Evidence from a randomised control trial in Nairobi, Kenya. BMJ Glob. Health 2018, 3, e000888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.; Rothschild, C.; Golub, G.; Omondi, G.N.; Kruk, M.E.; McConnell, M. Measuring the impact of cash transfers and behavioural ‘nudges’ on maternity care in Nairobi, Kenya. Health Aff. 2017, 36, 1956–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baba-Ari, F.; Eboreime, E.A.; Hossain, M. Conditional cash transfers for maternal health interventions: Factors influencing uptake in North-Central Nigeria. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2018, 7, 934–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntoimo, L.F.; Okonofua, F.E.; Aikpitanyi, J.; Yaya, S.; Johnson, E.; Sombie, I.; Aina, O.; Imongan, W. Influence of women’s empowerment indices on the utilization of skilled maternity care: Evidence from rural Nigeria. J. Biosoc. Sci. 2020, 54, 77–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawole, O.I.; Adeoye, I.A. Women’s status within the household as a determinant of maternal health care use in Nigeria. Afr. Health Sci. 2015, 15, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganle, J.K. Why Muslim women in Northern Ghana do not use skilled maternal healthcare services at health facilities: A qualitative study. BMC Int Health Hum Rights 2015, 15, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.J.; Batey, M.; Holdsworth, L. Personality and health: The mediating role of trait emotional intelligence and work locus of control. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2009, 47, 470–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotter, J.B. Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychol. Monogr. 1966, 80, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachit, A.A.; Hussein, A.; Essa, H. Locus of control among pregnant adolescents and its relation to health outcomes. Afr. J. Biomed. Res. 2024, 27, 946–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shifrer, D. The contributions of parental, academic, school, and peer factors to differences by socioeconomic status in adolescents’ locus of control. Soc. Ment. Health 2019, 9, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobb-Clark, D.A.; Kassenboehmer, S.C.; Schurer, S. Healthy habits: The connection between diet, exercise, and locus of control. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2014, 98, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesavayuth, D.; Poyago-Theotoky, J.; Tran, D.B.; Zikos, V. Locus of control, health and healthcare utilization. Econ. Model. 2020, 86, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aikpitanyi, J.; Okonofua, F.; Ntoimo, L.; Tubeuf, S. Locus of control and self-esteem as predictors of maternal and child healthcare services utilization in Nigeria. Front. Health Serv. 2022, 2, 847721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moutafi, J.; Furnham, A.; Tsaousis, I. Is the relationship between intelligence and trait neuroticism mediated by test anxiety? Personal. Individ. Differ. 2006, 40, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, H.S.; Kern, M.L.; Reynolds, C.A. Personality and health, subjective well-being, and longevity. J. Pers. 2010, 78, 179–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, B.W.; Kuncel, N.R.; Shiner, R.; Caspi, A.; Goldberg, L.R. The power of personality: The comparative validity of personality traits, socioeconomic status, and cognitive ability for predicting important life outcomes. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2007, 2, 313–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakeri, M.; Jafarirad, S.; Amani, R.; Cheraghian, B.; Najafian, M. A longitudinal study on the relationship between mother’s personality trait and eating behaviors, food intake, maternal weight gain during pregnancy, and neonatal birth weight. Nutr. J. 2020, 19, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M. Psychological and neurobiological mechanisms underlying the decline of maternal behavior. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2020, 116, 164–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weston, S.J.; Jackson, J.J. How do people respond to health news? The role of personality traits. Psychol. Health 2016, 31, 637–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jomeen, J.; Martin, C.R. The impact of choice of maternity care on psychological health outcomes for women during pregnancy and the postnatal period. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2008, 14, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horner, K.L. Locus of control, neuroticism, and stressors: Combined influences on reported physical illness. Personal. Individ. Differ. 1996, 21, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asselmann, E.; Kunas, S.L.; Wittchen, H.-U.; Martini, J. Maternal personality, social support, and changes in depressive, anxiety, and stress symptoms during pregnancy and after delivery: A prospective-longitudinal study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0237609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winship, C.; Mare, R.D. Structural equations and path-analysis for discrete data. Am. J. Sociol. 1983, 89, 54–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Central Office of Research. Edo State Statistical Yearbook (2014–2020). Available online: http://mda.edostate.gov.ng/budget/edo-state-statisticalyearbook-2014-2020/ (accessed on 13 September 2021).

- Federal Government of Nigeria. Integrating Primary Health Care Governance in Nigeria (PHC Under One Roof): Implementation Manual National Health Care Development Agency; Federal Government of Nigeria: Abuja, Nigeria, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Yaya, S.; Okonofua, F.; Ntoimo, L.; Kadio, B.; Deuboue, R.; Imongan, W.; Balami, W. Increasing women’s access to skilled pregnancy care to reduce maternal and perinatal mortality in rural Edo State, Nigeria: A randomized controlled trial. Glob. Health Res. Policy 2018, 3, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okonofua, F.; Ntoimo, L.; Ogungbangbe, J.; Anjorin, S.; Imongan, W.; Yaya, S. Predictors of women’s utilization of primary health care for skilled pregnancy care in rural Nigeria. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2018, 18, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearlin, L.I.; Schooler, C. The structure of coping. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1978, 19, 2–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronbach, L.J. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 1951, 16, 297–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, O.P.; Srivastava, S. The Big Five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and theoretical perspectives. In Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research, 2nd ed.; Pervin, L.A., John, O.P., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999; pp. 102–138. [Google Scholar]

- Efron, B. Better bootstrap confidence intervals. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1987, 82, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rijnhart, J.J.M.; Twisk, J.W.R.; Eekhout, I.; Heymans, M.W. Comparison of logistic regression-based methods for simple mediation analysis with a dichotomous outcome variable. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2019, 19, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imai, K.; Keele, L.; Tingley, D. A general approach to causal mediation analysis. Psychol. Methods 2010, 15, 309–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, M.E.; Francis, A.J. Locus of control beliefs mediate the relationship between religious functioning and psychological health. J. Relig. Health 2012, 51, 774–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenberg, N.E.; Swanson, M. Rural Religious Leaders’ Perspectives on their Communities’ Health Priorities and Health. South Med. J. 2017, 110, 447–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adedini, S.A.; Babalola, S.; Ibeawuchi, C.; Omotoso, O.; Akiode, A.; Odeku, M. Role of religious leaders in promoting contraceptive use in Nigeria: Evidence from the Nigerian urban reproductive health initiative. Glob. Health Sci. Pract. 2018, 6, 500–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aikpitanyi, J.; Yacin, F.; Tubeuf, S. Effectiveness of behavioural change interventions to influence maternal and child healthcare-seeking behaviours in low and lower-middle-income countries: A systematic review of literature. Afr. J. Reprod. Health 2024, 28, 127–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiner, R.; Caspi, A. Personality differences in childhood and adolescence: Measurement, development, and consequences. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 2003, 44, 2–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Obs. | Mean | Std. Dev | Min | Max | Prop. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Explanatory | ||||||

| LOC | 1411 | 25.37 | 4.53 | 7 | 35 | |

| Internal | 0.113 | |||||

| External | 0.887 | |||||

| Neuroticism | 1411 | 16.19 | 3.41 | 5 | 25 | |

| Low | 0.236 | |||||

| High | 0.763 | |||||

| Outcome | ||||||

| SBA | 1359 | 0 | 1 | |||

| No | 0.122 | |||||

| Yes | 0.878 |

| Locus of Control | Neuroticism | Skilled Birth Care | Age | Education | Partner’s Education | Healthcare Decision | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Locus of control | 1.000 | ||||||

| Neuroticism | 0.168 *** | 1.000 | |||||

| Skilled birth care | −0.131 *** | 0.099 *** | 1.000 | ||||

| Age | −0.186 *** | −0.117 *** | 0.015 | 1.000 | |||

| Education | −0.009 | −0.043 | 0.137 *** | −0.242 *** | 1.000 | ||

| Partner’s education | 0.115 *** | 0.013 | 0.118 *** | −0.152 *** | 0.541 *** | 1.000 | |

| Healthcare decision | −0.097 *** | 0.112 *** | 0.005 | −0.084 *** | −0.004 | 0.016 | 1.000 |

| Variables | (1) Coeff. (Std. Err) | (2) Coeff. (Std. Err) |

|---|---|---|

| External locus of control | 0.369 *** (0.090) | 0.224 ** (0.091) |

| Age | ||

| 15–24 | Ref | |

| 25–34 | −0.325 (0.271) | |

| 35–44 | −0.683 ** (0.332) | |

| >44 | −1.464 *** (0.415) | |

| Education | ||

| None | Ref | |

| Primary | 0.312 (0.312) | |

| Secondary | −0.118 (0.337) | |

| Higher | −1.407 ** (0.555) | |

| Cohabitation status | ||

| Cohabiting | Ref | |

| Not cohabiting | −0.845 *** (0.187) | |

| Occupation | ||

| Not working | Ref | |

| Working | 0.422 (0.245) | |

| Religion | ||

| Christianity | Ref | |

| Islam | 1.515 ** (0.516) | |

| Others | 0.875 (0.762) | |

| Number of children | ||

| 1 | Ref | |

| 2 | −0.537 ** (0.224) | |

| 3 | −1.933 ** (0.609) | |

| Partner’s age | ||

| 15–37 | Ref | |

| 38–57 | −0.139 (0.244) | |

| 58–77 | −1.448 ** (0.503) | |

| >77 | −1.933 ** (0.609) | |

| Partner’s education | ||

| None | Ref | |

| Primary | 0.752 ** (0.321) | |

| Secondary | 0.539 (0.318) | |

| Higher | 0.308 (0.396) | |

| Partner’s occupation | ||

| Not working | Ref | |

| Working | 0.069 (0.295) | |

| Healthcare decision | ||

| Self | Ref | |

| Partner | 0.540 (0.290) | |

| Both | 1.037 *** (0.298) | |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.0110 | 0.0890 |

| Number of observations | 1411 | 1411 |

| Variables | (3) Coeff. (Std. Err) | (4) Coeff. (Std. Err) |

|---|---|---|

| External locus of control | −0.330 *** (0.103) | −0.316 *** (0.104) |

| Neuroticism | −0.073 (0.028) *** | |

| Age | ||

| 15–24 | Ref | Ref |

| 25–34 | −0.018 (0.283) | −0.036 (0.285) |

| 35–44 | −0.038 (0.331) | −0.096 (0.333) |

| >44 | 0.291 (0.449) | 0.142 (0.453) |

| Education | ||

| None | Ref | Ref |

| Primary | 0.345 (0.254) | 0.382 (0.256) |

| Secondary | 0.924 ** (0.302) | 0.933 ** (0.304) |

| Higher | 0.742 (0.574) | 0.645 (0.576) |

| Cohabitation status | ||

| Cohabiting | Ref | Ref |

| Not cohabiting | 0.742 *** (0.198) | 0.672 *** (0.202) |

| Occupation | ||

| Not working | Ref | Ref |

| Working | −0.088 (0.249) | −0.056 (0.250) |

| Religion | ||

| Christianity | Ref | Ref |

| Islam | −0.516 (0.411) | −0.438 (0.411) |

| Others | 0.648 (0.794) | 0.615 (0.783) |

| Number of children | ||

| 1 | Ref | Ref |

| 2 | 0.149 (0.229) | 0.079 (0.231) |

| 3 | −0.062 (0.640) | −0.220 (0.645) |

| Partner’s age | ||

| 15–37 | Ref | Ref |

| 38–57 | 0.266 (0.238) | 0.266 (0.239) |

| 58–77 | 1.179 (0.613) | 1.122 (0.615) |

| >77 | −0.302 (0.583) | −0.494 (0.587) |

| Partner’s education | ||

| None | Ref | Ref |

| Primary | 0.552 (0.278) | 0.576 ** (0.280) |

| Secondary | 0.586 ** (0.279) | 0.623 ** (0.281) |

| Higher | 0.932 ** (0.399) | 0.929 ** (0.401) |

| Partner’s occupation | ||

| Not working | Ref | Ref |

| Working | −0.228 (0.301) | −0.206 (0.303) |

| Healthcare decision | ||

| Self | Ref | Ref |

| Partner | 0.599 ** (0.277) | 0.634 ** (0.279) |

| Both | 0.359 (0.281) | 0.413 (0.283) |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.0786 | 0.0855 |

| Prob. | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| Number of observations | 1359 | 1359 |

| Model Pathways | β | Std. Err. | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Estimated direct effects: | ||||

| Path a (LOC -> NEU) | 0.369 *** | 0.090 | 0.048 | 0.134 |

| Path b (NEU -> SBA) | −0.073 *** | 0.028 | −0.550 | −0.144 |

| Path c (LOC -> SBA) | −0.330 *** | 0.103 | −0.555 | −0.171 |

| Path c’ (LOC -> SBA) | −0.316 *** | 0.104 | −0.529 | −0.146 |

| Bootstrap test for indirect effect | 95% bias-corrected confidence interval | |||

| Lower | Upper | |||

| LOC -> NEU -> SBA | −0.084 *** | 0.027 | −0.514 | −0.153 |

| Variables | Coeff. (Std. Err) | p-Value | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Neuroticism | −0.261 ** (0.106) | 0.013 | −0.468 | −0.054 |

| Locus of control | −0.089 *** (0.021) | 0.000 | −0.131 | −0.048 |

| Rho at which AME = 0 | −0.20 | |||

| R2_MR2_Y at which AME = 0: | 0.04 | |||

| R2_M~R2_Y~ at which AME = 0: | 0.0314 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aikpitanyi, J.; Guillon, M. Locus of Control and Utilization of Skilled Birth Care in Nigeria: The Mediating Influence of Neuroticism. Populations 2025, 1, 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/populations1020011

Aikpitanyi J, Guillon M. Locus of Control and Utilization of Skilled Birth Care in Nigeria: The Mediating Influence of Neuroticism. Populations. 2025; 1(2):11. https://doi.org/10.3390/populations1020011

Chicago/Turabian StyleAikpitanyi, Josephine, and Marlène Guillon. 2025. "Locus of Control and Utilization of Skilled Birth Care in Nigeria: The Mediating Influence of Neuroticism" Populations 1, no. 2: 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/populations1020011

APA StyleAikpitanyi, J., & Guillon, M. (2025). Locus of Control and Utilization of Skilled Birth Care in Nigeria: The Mediating Influence of Neuroticism. Populations, 1(2), 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/populations1020011