Projected Demographic Trends in the Likelihood of Having or Becoming a Dementia Family Caregiver in the U.S. Through 2060

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Differences by Race and Gender

1.2. Potential Demographic Drivers

1.3. Microsimulation Models and Prior Work on Family Care Projections

1.4. Current Study

- What are the population dynamics influencing the availability of family care to U.S. adults ages 65 and over with dementia?

- What proportion of individuals with dementia are expected to have no surviving spouse, sibling, or children who could provide care?

- How will this change with time?

- How is this expected to differ by race and gender?

- What are the population dynamics influencing the likelihood of being a potential caregiver to someone with dementia among the U.S. population ages 15 and over without dementia?

- What proportion of individuals ages 15 and over will be a potential caregiver to a family member with dementia?

- How will this change with time?

- How is this expected to differ by race and gender?

- Who among potential caregivers’ family members will be most likely to develop dementia (e.g., grandparents, parents, spouse, or siblings)?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data and Modeling

2.2. Analytic Approach

2.3. Kinship Measures

3. Results

3.1. Changes over Time in Family Caregiver Availability to People with Dementia, by Race and Gender

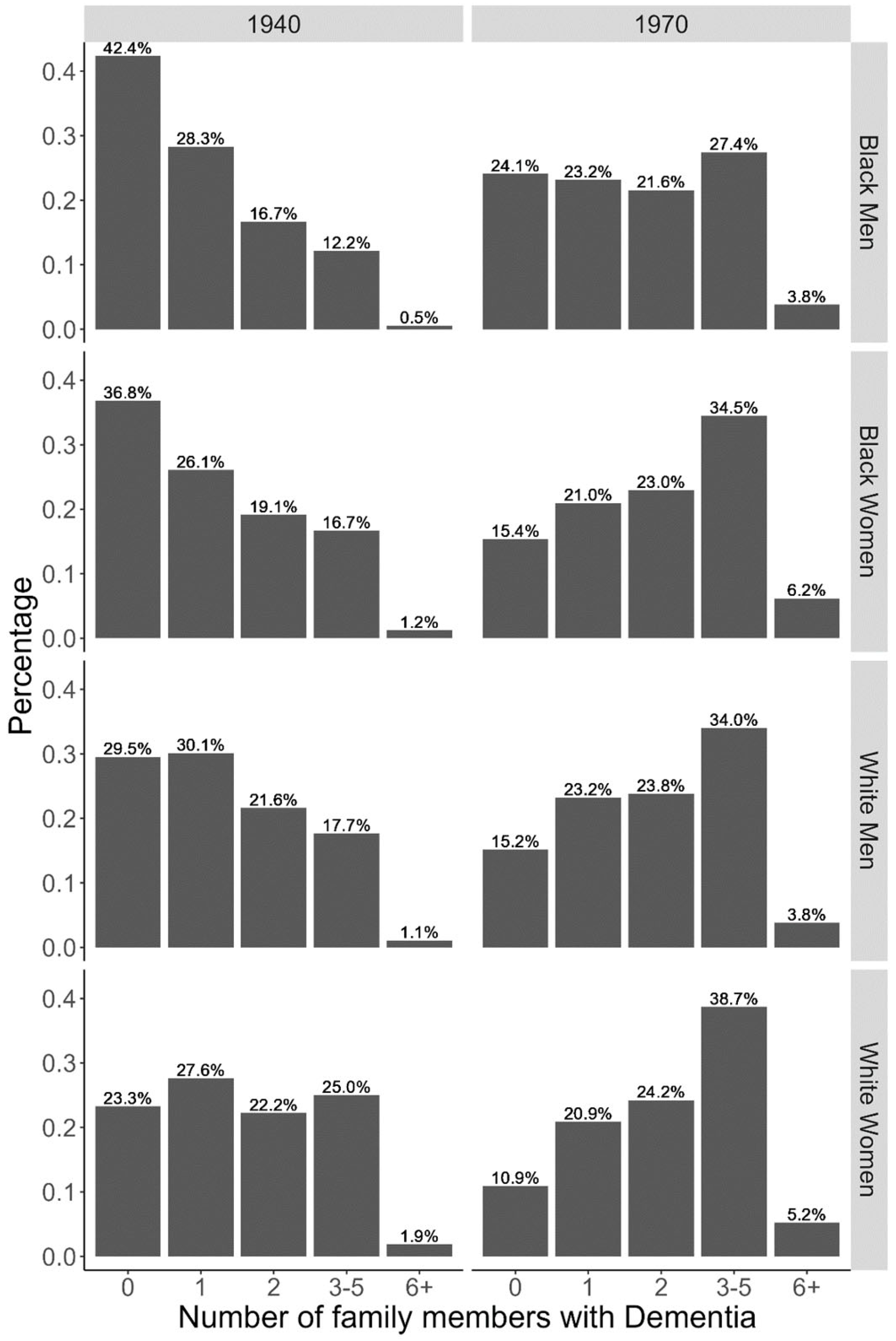

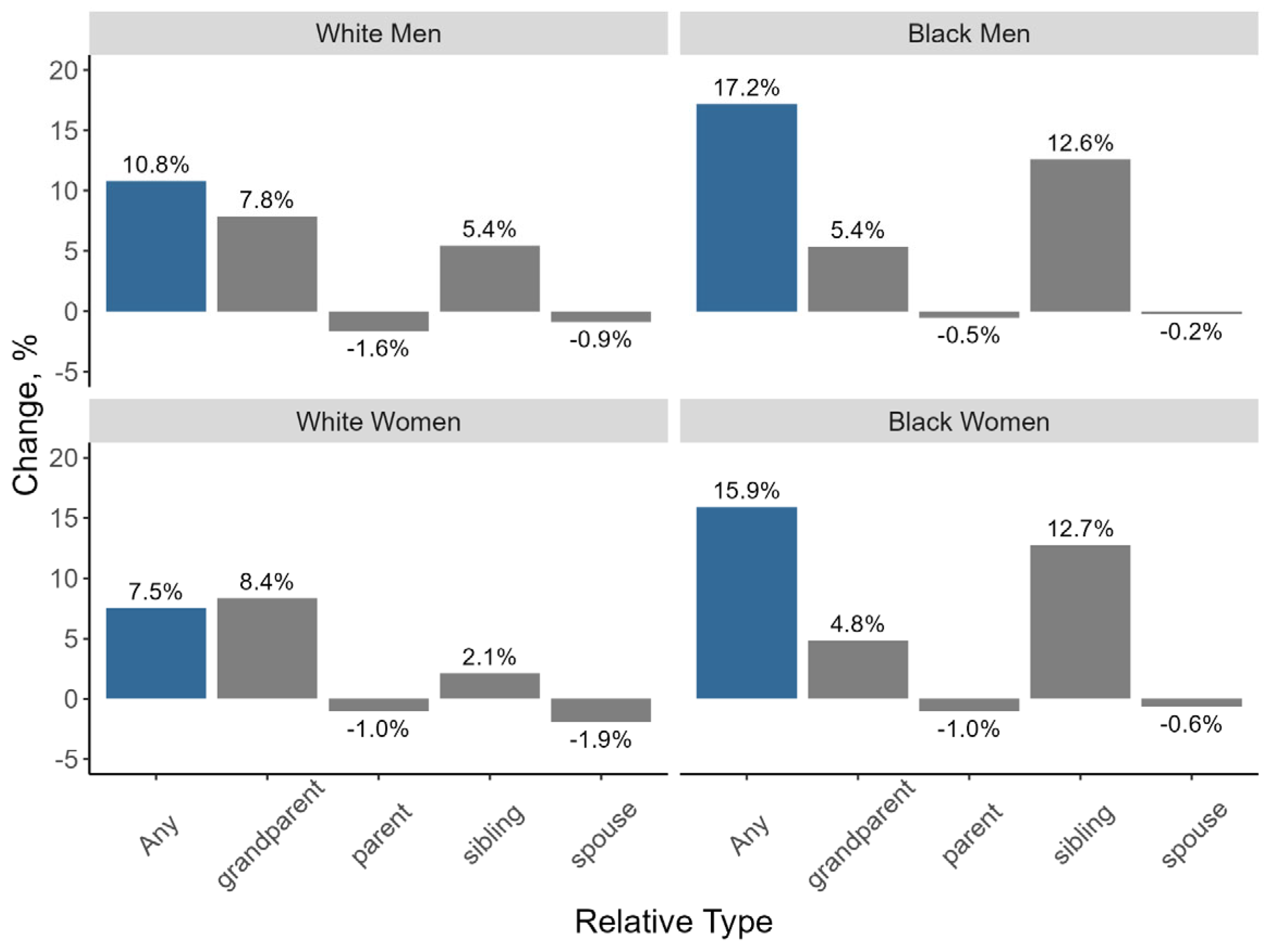

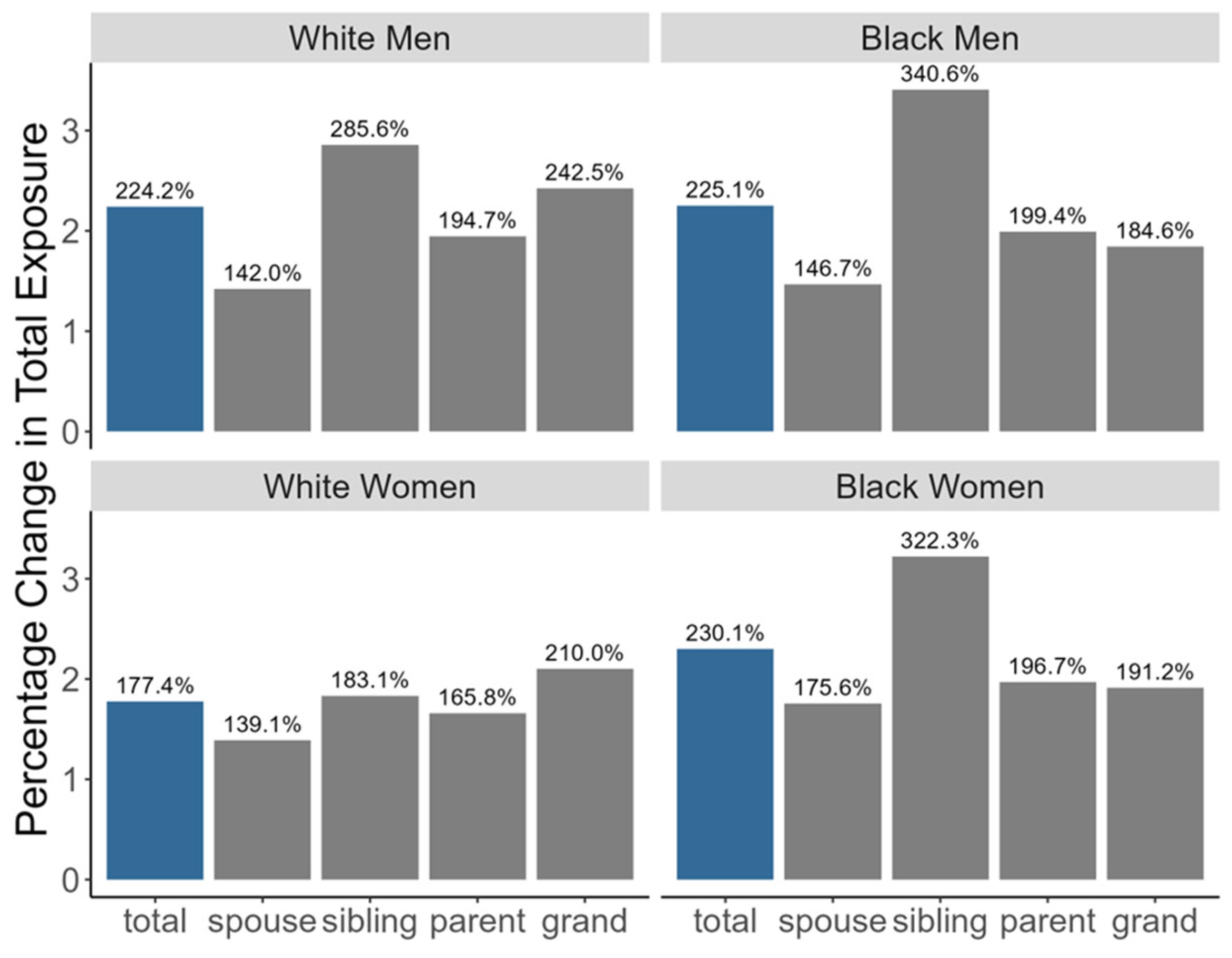

3.2. Changes over Time in Exposure to Family Members with Dementia Among Potential Caregivers, by Race and Gender

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alzheimer’s Association. Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures: Special Report Mapping a Better Future for Dementia Care Navigation. Alzheimers Dement. 2024, 19, 1598–1695. Available online: www.alz.org/getmedia/a7390c29-e4c0-4d3c-b000-377b6c112eea/alzheimers-facts-and-figures-special-report.pdf (accessed on 4 February 2025).

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hurd, M.D.; Martorell, P.; Delavande, A.; Mullen, K.J.; Langa, K.M. Monetary Costs of Dementia in the United States. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 1326–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhard, S.C.; Kassner, E.; Houser, A.; Mollica, R. Raising Expectations: A State Scorecard on Long-Term Services and Supports for Older Adults, People with Physical Disabilities, and Family Caregivers. 2011. Available online: https://ltsschoices.aarp.org/scorecard-report/2014/raising-expectations-2014 (accessed on 4 February 2025).

- Hudomiet, P.; Hurd, M.D.; Rohwedder, S. Dementia Prevalence in the United States in 2000 and 2012: Estimates Based on a Nationally Representative Study. J. Gerontol. Ser. B. 2018, 73, S10–S19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hudomiet, P.; Hurd, M.D.; Rohwedder, S. Trends in Inequalities in the Prevalence of Dementia in the United States. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2212205119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukadam, N.; Wolters, F.J.; Walsh, S.; Wallace, L.; Brayne, C.; Matthews, F.E.; Sacuiu, S.; Skoog, I.; Seshadri, S.; Beiser, A.; et al. Changes in Prevalence and Incidence of Dementia and Risk Factors for Dementia: An Analysis from Cohort Studies. Lancet Public Health 2024, 9, e443–e460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedman, E.M.; Shih, R.A.; Langa, K.M.; Hurd, M.D. US Prevalence and Predictors of Informal Caregiving for Dementia. Health Aff. 2015, 34, 1637–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris-Kojetin, L.D.; Sengupta, M.; Park-Lee, E.; Valverde, R. Long-Term Care Services in the United States: 2013 Overview; National Center for Health Statistics: 2013. Available online: www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nsltcp/long_term_care_services_2013.pdf (accessed on 4 February 2025).

- Redfoot, D.; Feinberg, L.; Houser, A.N. The Aging of the Baby Boom and the Growing Care Gap: A Look at Future Declines in the Availability of Family Caregivers; AARP Public Policy Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; Available online: https://www.caregiver.org/uploads/2023/02/baby-boom-and-the-growing-care-gap-insight-AARP-ppi-ltc.pdf (accessed on 4 February 2025).

- SCAN Foundation. Who Pays for Long-Term Care in the U.S.? SCAN Foundation: Long Beach, CA, USA, 2013; Available online: https://www.thescanfoundation.org/sites/default/files/who_pays_for_ltc_us_jan_2013_fs.pdf (accessed on 4 February 2025).

- Bookman, A.; Kimbrel, D. Families and Elder Care in the Twenty-First Century. Future Child. 2011, 21, 117–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.W.; Wiener, J.M. A Profile of Frail Older Americans and Their Caregivers; Urban Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2006; Available online: https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/42946/311284-A-Profile-of-Frail-Older-Americans-and-Their-Caregivers.PDF (accessed on 4 February 2025).

- Matthews, K.A.; Xu, W.; Gaglioti, A.H.; Holt, J.B.; Croft, J.B.; Mack, D.; McGuire, L.C. Racial and Ethnic Estimates of Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias in the United States (2015–2060) in Adults Aged ≥ 65 years. Alzheimers Dement. 2019, 15, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Crimmins, E.M.; Zissimopoulos, J.M. Sex, Race, and Age Differences in Prevalence of Dementia in Medicare Claims and Survey Data. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2021, 76, 596–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.; Heisler, M.; Norton, E.C.; Langa, K.M.; Cho, T.-C.; Connell, C.M. Family Care Availability and Implications for Informal and Formal Care Used by Adults with Dementia in the US: Study examines family care availability and implications for informal and form care used by adults with Dementia in the United States. Health Aff. 2021, 40, 1359–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, L.J.; Fabius, C. Who’s Helping Whom? Examination of Care Arrangements for Racially and Ethnically Diverse People Living with Dementia in the Community. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2022, 41, 2589–2593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freedman, V.A.; Agree, E.M.; Seltzer, J.A.; Birditt, K.S.; Fingerman, K.L.; Friedman, E.M.; Lin, I.-F.; Margolis, R.; Park, S.S.; Patterson, S.E.; et al. The Changing Demography of Late-Life Family Caregiving: A Research Agenda to Understand Future Care Networks for an Aging US Population. Gerontologist 2024, 64, gnad036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J.A.; Hamilton, B.E.; Osterman, M.J.K. Births in the United States, 2013. NCHS Data Brief. 2014, 175, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- McGarry, K.M. Caring for the Elderly: The Role of Adult Children. In Inquiries in the Economics of Aging; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1998; pp. 133–166. [Google Scholar]

- Soldo, B.J.; Wolf, D.A.; Agree, E.M. Family, Households, and Care Arrangements of Frail Older Women: A Structural Analysis. J. Gerontol. 1990, 45, S238–S249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitze, G.; Logan, J. Sons, daughters, and Intergenerational Social Support. J. Marriage Fam. 1990, 52, 420–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, R.; Cafferata, G.L.; Sangl, J. Caregivers of the Frail Elderly: A National Profile. Gerontologist 1987, 27, 616–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szinovacz, M.E.; Davey, A. Changes in Adult Children’s Participation in Parent Care. Ageing Soc. 2013, 33, 667–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spillman, B.C.; Freedman, V.A.; Kasper, J.D.; Wolff, J.L. Change Over Time in Caregiving Networks for Older Adults With and Without Dementia. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2020, 75, 1563–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, J.L.; Kasper, J.D. Caregivers of Frail Elders: Updating a National Profile. Gerontologist 2006, 46, 344–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, M.; Ganong, L. Changing Families, Changing Responsibilities: Family Obligations Following Divorce and Remarriage; Psychology Press: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, I.F. Consequences of Parental Divorce for Adult Children’s Support of Their Frail Parents. J. Marriage Fam. 2008, 70, 113–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias, E. Changes in Life Expectancy by Race and Hispanic Origin in the United States, 2013–2014. NCHS Data Brief 2016, 244, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Baldini, M.; Mazzaferro, C.; Morciano, M. Assessing the Implications of Long Term Care Policies in Italy: A Microsimulation Approach. Università degli Studi di Modena e Reggio Emilia, Dipartimento di Economia Politica. Politica Econ. 2008, 24, 47–72. [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso, T.; Oliveira, M.D.; Barbosa-Póvoa, A.; Nickel, S. Modeling the Demand for Long-Term Care Services Under Uncertain Information. Health Care Manag. Sci. 2012, 15, 385–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eggink, E.; Woittiez, I.; Ras, M. Forecasting the Use of Elderly Care: A Static Micro-Simulation Model. Eur. J. Health Econ. 2015, 17, 681–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laditka, S.B.; Laditka, J.N. Effects of Improved Morbidity Rates on Active Life Expectancy and Eligibility for Long-Term Care Services. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2001, 20, 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lymer, S.; Brown, L.; Harding, A.; Yap, M. Predicting the Need for Aged Care Services at the Small Area Level: The CAREMOD Spatial Microsimulation Model. Int. J. Microsimulation 2009, 2, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spetz, J.; Trupin, L.; Bates, T.; Coffman, J.M. Future Demand for Long-Term Care Workers Will be Influenced by Demographic and Utilization Changes. Health Aff. 2015, 34, 936–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittenberg, R.; Comas-Herrera, A.; King, D.; Malley, J.; Pickard, L.; Darton, R. Future Demand for Long-Term Care, 2002 to 2041: Projections of Demand for Long-Term Care for Older People in England. 2006. Available online: https://kar.kent.ac.uk/88828/1/dp2514.pdf (accessed on 4 February 2025).

- US Dept of Health and Human Services. The Future Supply of Long Term Care Workers in Relation to the Aging Baby-Boom Generation 2003; Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. Available online: https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/private/pdf/72961/ltcwork.pdf (accessed on 4 February 2025).

- Fukawa, T. Household Projection and Its Application to Health/Long-Term Care Expenditures in Japan Using INAHSIM-II. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 2011, 29, 52–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.W.; Toohey, D.; Wiener, J.M. Meeting the Long-Term Care Needs of the Baby Boomers: How Changing Families Will Affect Paid Helpers and Institutions; Urban Institute Project TR: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Pickard, L.; Wittenberg, R.; Comas-Herrera, A.; King, D.; Malley, J. Care by Spouses, Care by Children: Projections of Informal Care for Older People in England to 2031. Soc. Policy Soc. 2007, 6, 353–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdery, A.M.; Margolis, R. Projections of White and Black Older Adults Without Living Kin in the United States, 2015 to 2060. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 11109–11114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, K.; Song, X.; Caswell, H. Kinship and Care: Racial Disparities in Potential Dementia Caregiving in the US from 2000 to 2060. J. Gerontol. Ser. A: Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2024, 79, S32–S41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammel, E.A. The SOCSIM Demographic-Sociological Microsimulation Program: Operating Manual; Institute of International Studies, University of California: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Wachter, K.W. Kinship Resources for the Elderly. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 1997, 352, 1811–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutter, C.M.; Edochie, I.; Friedman, E.M.; Slaughter, M.E.; Weden, M.M. A Simple Method for Simulating Dementia Onset and Death Within an Existing Demographic Model. Med. Decis. Mak. 2022, 42, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Margolis, R.; Verdery, A.M. A Cohort Perspective on the Demography of Grandparenthood: Past, Present, and Future Changes in Race And Sex Disparities in the United States. Demography 2019, 56, 1495–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health and Retirement Study, Public Use Dataset; Produced and Distributed by the University of Michigan with Funding from the National Institute on Aging (grant numbers NIA U01AG009740 and NIA R01AG073289): Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2016.

- Koller, D.; Bynum, J.P. Dementia in the USA: State Variation in Prevalence. J. Public Health 2015, 37, 597–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayeda, E.R.; Glymour, M.M.; Quesenberry, C.P.; Johnson, J.K.; Pérez-Stable, E.; Whitmer, R.A. Survival After Dementia Diagnosis in Five Racial/Ethnic Groups. Alzheimers Dement. 2017, 13, 761–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, K.E.; Hart, J.L.; Rosania, M.U.; Coe, N.B. Youth Caregivers of Adults in the United States: Prevalence and the Association Between Caregiving and Education. Demography 2024, 61, 829–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prudencio, G.; Young, H. Caregiving in the US 2020: What Does the Latest Edition of this Survey Tell US About Their Contributions and Needs? Innov. Aging 2020, 4, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Colditz, G.A.; Berkman, L.F.; Kawachi, I. Caregiving and risk of coronary heart disease in US women: A prospective study. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2003, 24, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, D.L.; Perkins, M.; Wadley, V.G.; Temple, E.M.; Haley, W.E. Family Caregiving and Emotional Strain: Associations with Quality of Life in a Large National Sample of Middle-Aged and Older Adults. Qual. Life Res. 2009, 18, 679–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, R.; Beach, S.R. Caregiving as a Risk Factor for Mortality: The Caregiver Health Effects Study. Jama 1999, 282, 2215–2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fahle, S.; McGarry, K. How Caregiving for Parents Reduces Women’s Employment. Overtime Am. Aging Workforce Future Work. Longer 2022, 213. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.; Tang, F.; Kim, K.H.; Albert, S.M. The Vicious Cycle of Parental Caregiving and Financial Well-Being: A Longitudinal Study of Women. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2015, 70, 425–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, L.; Morton, D.; van Rooyen, D. Family Dynamics in Dementia Care: A Phenomenological Exploration of the Experiences of Family Caregivers of Relatives with Dementia. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2022, 29, 861–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szinovacz, M.E. Caring for a Demented Relative at Home: Effects on Parent–Adolescent Relationships and Family Dynamics. J. Aging Stud. 2003, 17, 445–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, E.M.; Kennedy, D.P. Typologies of Dementia Caregiver Support Networks: A Pilot Study. Gerontologist 2021, 61, 1221–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No Living Spouse (%) | No Living Spouse or Children (%) | No Living Spouse, Children, or Siblings (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020–2024 | 2055–2059 | Change | 2020–2024 | 2055–2059 | Change | 2020–2024 | 2055–2059 | Change | |

| White Men | 37.1 | 31.8 | −5.3 | 7.0 | 10.1 | 3.1 | 2.0 | 3.5 | 1.5 |

| Black Men | 51.9 | 49.7 | −2.2 | 9.8 | 13.7 | 4.1 | 2.5 | 3.4 | 0.9 |

| White Women | 69.8 | 54.5 | −15.3 | 8.5 | 11.8 | 3.3 | 3.2 | 4.1 | 0.9 |

| Black Women | 78.0 | 65.8 | −12.2 | 12.8 | 17.3 | 4.5 | 4.7 | 4.3 | −0.4 |

| % Exposed | % Change in Duration of Lifetime Exposure (in Months) | % Exposed to 2+ Family Members | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1940 | 1970 | 1940–1970 | 1940 | 1970 | |

| White Men | 12.2 | 15.4 | 224.2 | 5.2 | 6.3 |

| Black Men | 12.8 | 16.2 | 225.1 | 5.6 | 6.4 |

| White Women | 12.2 | 15.0 | 177.4 | 4.5 | 5.0 |

| Black Women | 12.3 | 16.3 | 230.0 | 4.3 | 5.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Friedman, E.M.; Wang, J.; Weden, M.M.; Slaughter, M.E.; Shih, R.A.; Rutter, C.M. Projected Demographic Trends in the Likelihood of Having or Becoming a Dementia Family Caregiver in the U.S. Through 2060. Populations 2025, 1, 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/populations1020010

Friedman EM, Wang J, Weden MM, Slaughter ME, Shih RA, Rutter CM. Projected Demographic Trends in the Likelihood of Having or Becoming a Dementia Family Caregiver in the U.S. Through 2060. Populations. 2025; 1(2):10. https://doi.org/10.3390/populations1020010

Chicago/Turabian StyleFriedman, Esther M., Jessie Wang, Margaret M. Weden, Mary E. Slaughter, Regina A. Shih, and Carolyn M. Rutter. 2025. "Projected Demographic Trends in the Likelihood of Having or Becoming a Dementia Family Caregiver in the U.S. Through 2060" Populations 1, no. 2: 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/populations1020010

APA StyleFriedman, E. M., Wang, J., Weden, M. M., Slaughter, M. E., Shih, R. A., & Rutter, C. M. (2025). Projected Demographic Trends in the Likelihood of Having or Becoming a Dementia Family Caregiver in the U.S. Through 2060. Populations, 1(2), 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/populations1020010