Zero-Sum Beliefs About the Human–Nature Relationship: The Role of Social Dominance Orientation, Tolerance of Ambiguity, and Need for Cognition

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Zero-Sum Beliefs Between Nature and Humanity

1.2. Social Dominance Orientation

1.3. Tolerance of Ambiguity

1.4. Need for Cognition

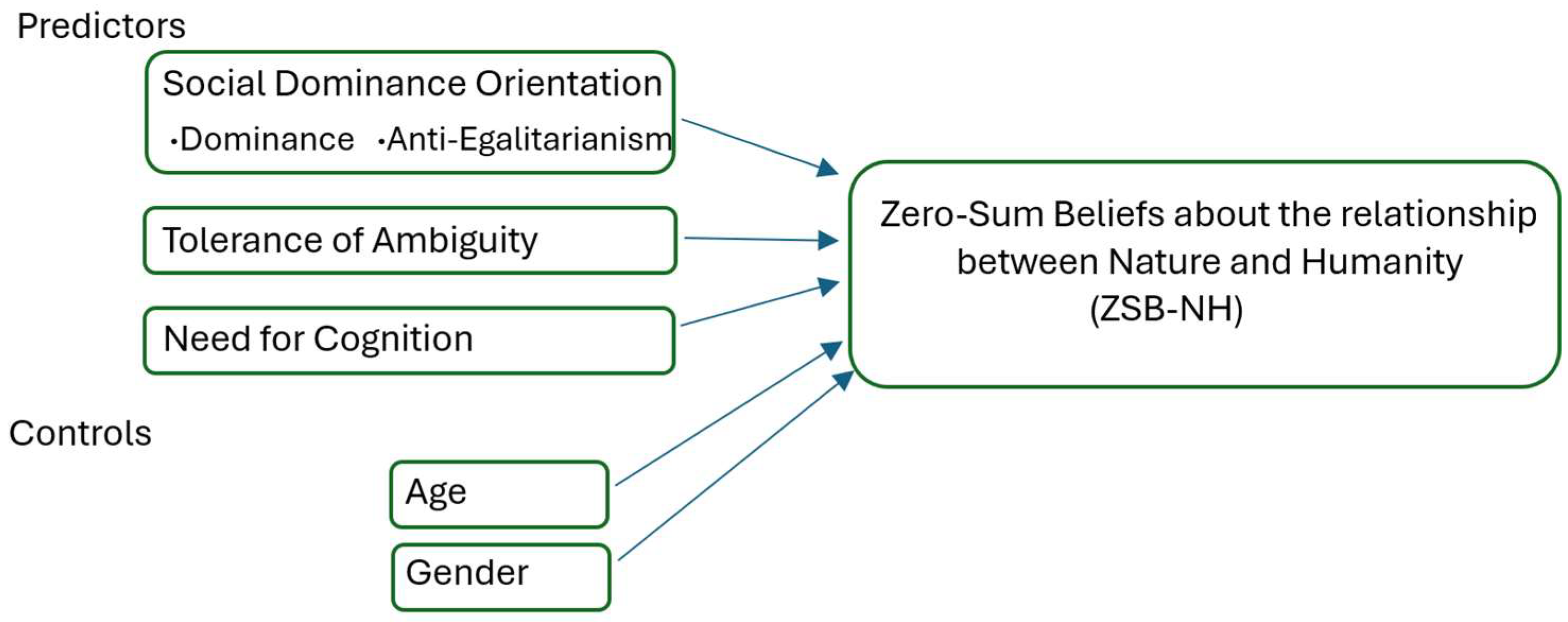

1.5. The Current Study

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Participants

Sampling Procedure

2.2. Design and Materials

2.2.1. Zero-Sum Beliefs Between Nature and Humanity

2.2.2. Social Dominance Orientation

2.2.3. Tolerance of Ambiguity

2.2.4. Need for Cognition

2.3. Procedure

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics and Preliminary Analyses

3.2. Inferential Statistics

3.3. Supplementary Analyses

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications

4.1.1. Theoretical Implications

4.1.2. Practical Implications

4.2. Strengths, Limitations, and Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Andrews-Fearon, P., & Davidai, S. (2023). Is status a zero-sum game? Zero-sum beliefs increase people’s preference for dominance but not prestige. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 152(2), 389–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews-Fearon, P., & Götz, F. M. (2024). The zero-sum mindset. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 127(4), 758–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, S. H., Craig, R. K., Dernbach, J. C., Hirokawa, K., Krakoff, S., Owley, J., Powers, M., Roesler, S., Rosenbloom, J., Ruhl, J. B., Salzman, J., Scott, I., & Takacs, D. (2017). Beyond zero-sum environmentalism. Environmental Law Reporter, 191(47), 10328–10351. Available online: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/journal_articles/191 (accessed on 23 March 2024).

- Cacioppo, J. T., Petty, R. E., Feinstein, J. A., & Jarvis, W. B. G. (1996). Dispositional differences in cognitive motivation: The life and times of individuals varying in Need for Cognition. Psychological Bulletin, 119(2), 197–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D., & Pensini, P. (2024). The development of the zero-sum beliefs between nature and humanity scale. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 94, 102247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Davidai, S., & Tepper, S. J. (2023). The psychology of zero-sum beliefs. Nature Reviews Psychology, 2, 472–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeRoma, V. M., Martin, K. M., & Kessler, M. L. (2003). The relationship between tolerance for ambiguity and need for course structure. Journal of Instructional Psychology, 30(2), 104. [Google Scholar]

- Doise, W. (1986). Levels of explanation in social psychology. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Engwerda, J., & Pensini, P. (2025). Zero-sum beliefs between nature and humanity: The relationship with life satisfaction. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G., & Buchner, A. (2009). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 41(4), 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furnham, A., & Marks, J. (2013). Tolerance of ambiguity: A review of the recent literature. Psychology, 4(9), 717–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halabi, S., Dovidio, J. F., & Nadler, A. (2008). When and how do high status group members offer help: Effects of social dominance orientation and status threat. Political Psychology, 29, 841–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, J. L., Stevens, M. J., Bird, A., Mendenhall, M., & Oddou, G. (2010). The tolerance for ambiguity scale: Towards a more refined measure for international management research. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 34(1), 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, A. K., Sidanius, J., Pratto, F., Levin, S., Thomsen, L., Kteily, N., & Sheehy-Skeffington, J. (2012). Social dominance orientation: Revisiting the structure and function of a variable predicting social and political attitudes. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 38(5), 583–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jost, J. T., & van der Toorn, J. (2012). System justification theory. In P. A. M. Van Lange, A. W. Kruglanski, & E. T. Higgins (Eds.), Handbook of theories of social psychology (pp. 313–343). Sage Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lins de Holanda Coelho, G., Hanel, P. H. P., & Wolf, L. J. (2018). The very efficient assessment of need for cognition: Developing a six-item version. Assessment, 27(8), 1870–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milfont, T. L., Bain, P. G., Kashima, Y., Corral-Verdugo, V., Pasquali, C., Johansson, L.-O., Guan, Y., Gouveia, V. V., Gardarsdottir, R. B., Doron, G., Bilewicz, M., Utsugi, A., Aragones, J. I., Steg, L., Soland, M., Park, J., Otto, S., Demarque, C., Wagner, C., … Einarsdottir, G. (2018). On the relation between Social Dominance Orientation and environmentalism: A 25-nation study. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 9(7), 802–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milfont, T. L., & Sibley, C. G. (2014). The hierarchy enforcement hypothesis of environmental exploitation: A social dominance perspective. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 55, 188–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petty, R. E., Brinol, P., Loersch, C., & McCaslin, M. J. (2009). The need for cognition. In M. R. Leary, & R. H. Hoyle (Eds.), Handbook of individual differences in social behavior (pp. 318–329). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pratto, F., Çidam, A., Stewart, A. L., Zeineddine, F. B., Aranda, M., Aiello, A., Chryssochoou, X., Cichocka, A., Cohrs, J. C., Durrheim, K., Eicher, V., Foels, R., Górska, P., Lee, I.-C., Licata, L., Liu, J. H., Li, L., Meyer, I., Morselli, D., … Henkel, K. E. (2013). Social dominance in context and in individuals: Contextual moderation of robust effects of social dominance orientation in 15 languages and 20 countries. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 4(5), 587–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratto, F., Stallworth, L. M., & Conway-Lanz, S. (1998). Social dominance orientation and the ideological legitimisation of social policy. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 28(20), 1853–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidanius, J., & Pratto, F. (2001). Social dominance: An intergroup theory of social hierarchy and oppression. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Smithson, M., Shou, Y., & Yu, A. (2017). Question word-order influences on covariate effects: Predicting zero-sum beliefs. Behaviormetrika, 44, 539–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefaniak, A., Mallett, R. K., & Wohl, M. J. A. (2020). Zero-sum beliefs shape advantaged allies’ support for collective action. European Journal of Social Psychology, 50, 1259–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, S., & Pensini, P. (2025). The personality correlates of zero-sum beliefs: The role of HEXACO personality dimensions in zero-sum beliefs in human-human and nature-human relations. Personality and Individual Differences, 247, 113428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubielevitch, E., Osborne, D., Milojev, P., & Sibley, C. G. (2023). Social dominance orientation and right-wing authoritarianism across the adult lifespan: An examination of aging and cohort effects. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 124(3), 544–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | M | SD | Score Range | 1 | 2 | 2a | 2b | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. ZSB-NH | 2.54 | 1.32 | 1–7 | — | ||||||

| 2. SDO | 2.55 | 1.15 | 1–7 | 0.59 *** | — | |||||

| 2a. SDO-Anti- Egalitarianism | 2.60 | 1.31 | 1–7 | 0.60 *** | n/a | — | ||||

| 2b. SDO- Dominance | 2.50 | 1.19 | 1–7 | 0.48 *** | n/a | 0.69 *** | — | |||

| 3. TA | 3.21 | 0.57 | 1–5 | −0.18 *** | −0.21 *** | −0.15 ** | −0.25 *** | — | ||

| 4. NC | 3.78 | 0.76 | 1–5 | −0.18 *** | −0.20 *** | −0.14 ** | −0.23 *** | 0.39 *** | — | |

| 5. Age | 52.77 | 18.56 | 18–90 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.12 * | −0.02 | 0.12 * | 0.11 * | — |

| 6. Gender | 1.61 | 0.49 | 1–2 | −0.24 *** | −0.31 *** | −0.33 *** | −0.23 *** | 0.07 | −0.11 * | −0.25 *** |

| Predictor | B | SE B | β | t | p | R2 | ΔR2 | F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | 0.062 | 0.057 | 11.63 | |||||

| Constant | 3.92 | 0.35 | 11.15 | <0.001 | ||||

| Age | −0.01 | 0.00 | −0.06 | −1.20 | 0.23 | |||

| Gender | −0.70 | 0.15 | −0.26 | −4.82 | <0.001 | |||

| Model 2 | 0.361 | 0.351 | 39.37 | |||||

| Constant | 2.11 | 0.54 | 3.92 | <0.001 | ||||

| Age | −0.02 | 0.00 | −0.05 | −1.00 | 0.32 | |||

| Gender | −0.24 | 0.13 | −0.09 | −1.86 | 0.06 | |||

| SDO | 0.63 | 0.05 | 0.55 | 11.68 | <0.001 | |||

| TA | −0.03 | 0.11 | −0.02 | −0.50 | 0.62 | |||

| NC | −0.12 | 0.08 | −0.07 | −1.4 | 0.16 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Taylor, M.; Pensini, P. Zero-Sum Beliefs About the Human–Nature Relationship: The Role of Social Dominance Orientation, Tolerance of Ambiguity, and Need for Cognition. Psychol. Int. 2025, 7, 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/psycholint7040089

Taylor M, Pensini P. Zero-Sum Beliefs About the Human–Nature Relationship: The Role of Social Dominance Orientation, Tolerance of Ambiguity, and Need for Cognition. Psychology International. 2025; 7(4):89. https://doi.org/10.3390/psycholint7040089

Chicago/Turabian StyleTaylor, Montana, and Pamela Pensini. 2025. "Zero-Sum Beliefs About the Human–Nature Relationship: The Role of Social Dominance Orientation, Tolerance of Ambiguity, and Need for Cognition" Psychology International 7, no. 4: 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/psycholint7040089

APA StyleTaylor, M., & Pensini, P. (2025). Zero-Sum Beliefs About the Human–Nature Relationship: The Role of Social Dominance Orientation, Tolerance of Ambiguity, and Need for Cognition. Psychology International, 7(4), 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/psycholint7040089