Abstract

In recent years, the science of sustainability has evolved in alignment with the United Nations’ 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, which aims to achieve a more just and sustainable world across various domains, including the environment, economy, society, and health and well-being. The International Olympic Committee has also established sustainability guidelines related to Olympic sports and athletes’ mental health. Additionally, the sustainability of sports training has already been explored, and the psychology of sustainability has generated a significant body of literature. This cultural and scientific movement has led to the emergence of the concept of psychological sustainability in elite sport, which can be defined as athletes’ capacity to maintain mental well-being, cognitive functioning, emotional resilience, and adaptive performance over time, particularly in response to environmental, social, training, and competitive stressors. This article revisits the existing literature to explore the connections between sustainability and elite sport psychology, resulting in the development of a model of psychological sustainability in sports training. This model aims to balance training procedures in a way that enhances athletic performance while safeguarding athletes’ mental health. Within this framework, an approach to psychological preparation for the Olympic Games is discussed, taking into account its various preparatory phases.

1. Introduction

In 1987, the UN Brundtland Commission introduced a widely recognized concept of sustainable development in the report Environment and Development: Our Common Future. This concept defines sustainable development as meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. The report highlights two key concepts: (i) the concept of needs, and (ii) the idea of limitations imposed by the environment’s capacity to meet present and future demands (Brundtland, 1987).

In 2015, the United Nations established the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, aiming to create a more just and sustainable world across various domains, including environmental, economic, social, and health and well-being domains.

The science of sustainability has emerged as an action-oriented, transdisciplinary field that integrates natural and social sciences, engineering, and the humanities, with the goal of generating practical knowledge to improve human well-being and promote long-term environmental integrity (Wu, 2019). While a significant focus is placed on ecological and environmental issues related to the preservation of the planet, social and psychological dimensions have also been the subject of study.

Although it is a relatively new area, the psychology of sustainability and sustainable development has made valuable contributions to the broader science of sustainability. On one hand, psychological processes influence environmental decision-making and behavior; on the other hand, the psychological environment affects the quality of life of individuals and communities (Di Fabio & Rosen, 2018). Specifically, the psychology of sustainability aims to support the development of individuals’ talents and well-being across various environments—natural, personal, social, organizational, community, global, and cross-cultural (Di Fabio & Rosen, 2018). In this context, psychology is seen as playing a key role in enhancing quality of life from a primary prevention perspective, addressing the individual, group, organizational, and inter-organizational levels (Di Fabio, 2017).

Di Fabio and Svicher (2021) highlight the role of psychology in human resource management by influencing the work environment and promoting employees’ psychological empowerment. This aligns with the concept of organizational sustainability, which involves meeting the current and future needs of workers (Ehnert, 2009). Similarly, Mohiuddin et al. (2022) suggest that the sustainability of human resource management is influenced by human resources practices, social and psychological factors, employer branding, and economic considerations.

Sport has been increasingly associated with sustainability. This connection is explicitly acknowledged in the United Nations’ 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development Goals, which states:

“Sport is also an important enabler of sustainable development. We recognize the growing contribution of sport to the realization of development and peace in its promotion of tolerance and respect and the contributions it makes to the empowerment of women and of young people, individuals and communities as well as to health, education and social inclusion objectives”.(United Nations, 2015, p. 10)

The Council of Europe’s Sport Division also affirms sport’s contribution to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly in supporting member states with issues such as doping, match-fixing, abuse of young athletes, and discrimination. Among the 17 goals, the main areas of focus include Goal 3 (Good Health and Well-Being), Goal 4 (Quality Education), Goal 5 (Gender Equality), Goal 10 (Reduced Inequalities), Goal 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities), and Goal 17 (Partnerships for the Goals) (Council of Europe, n.d.).

In addition, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) incorporated sustainability into its Agenda 21: Sport for Sustainable Development (IOC, 1999), providing a strategic framework to integrate sustainability into sport by promoting environmental protection, social inclusion, and economic responsibility. Regarding health protection, paragraph 3.1.5 emphasizes:

“The protection of health, an essential factor in the harmonious development of humankind, is closely related to the sustainable development of our society. The sports movement must play a dominant role in the health protection and promotion campaigns encompassed by UNCED Agenda 21. The governing bodies of the Olympic Movement will intensify their efforts to combat doping, which is perverting the practice of sport and jeopardizing the health of those involved in it”.(IOC, 1999)

In line with the IOC’s commitment to sustainable development, the International Summit on Sport and Sustainable Development was held in Paris on 25 July 2024—hosted by the IOC and the President of France—one day before the opening of the Olympic Games. The summit identified strategic priority areas for harnessing sport to advance global progress.

The intersection of sport and sustainability is also an emerging topic in scholarly literature, with recent contributions in both academic books (e.g., McCullough et al., 2022; Svensson et al., 2023) and peer-reviewed journals (e.g., Casper & Bunds, 2020; Cury et al., 2022; Hautbois & Desbordes, 2023; Lohmann et al., 2024).

2. The Psychological Sustainability of the Athletes

Most of the existing literature and initiatives linking sustainability with sport focus on the role of sport as a vehicle for promoting global sustainability. This concept is referred to by Triantafyllidis and Mallen (2022) as sport for sustainable development. The authors propose that this represents the second stage of sustainable development in sport, which follows an initial stage termed sustainable development of sport. This first stage emphasizes the implementation of internal sustainability practices within sport itself—a process the authors describe as endosustainability (Triantafyllidis & Mallen, 2022). Within this framework, the athlete—who is the central actor in sport—is included in the endosustainable process. This involves the athlete’s journey toward excellence, encompassing both physical and mental health, thus positioning the athlete as a sustainable entity (Triantafyllidis & Mallen, 2022). Consequently, alongside the objective of achieving excellence in performance, sports preparation and training processes must also prioritize the preservation and enhancement of athletes’ physical and mental health and psychological well-being. This dual objective—enhancing performance while protecting mental health—is captured in the concept of antifragility. According to Taleb (2012), antifragility refers to the robustization of systems to enable individuals and organizations to withstand and grow from crises and stressful situations.

The concept of performance in sport is multidimensional, involving an interactive relationship between physiological and psychological components. It is defined by the athlete’s ongoing ability to adapt to unforeseen environmental challenges in order to meet or exceed established performance standards (Kellmann et al., 2018; Portenga et al., 2017).

In relation to Goal 3 of the Sustainable Development Goals, paragraph 9.1 of the Routledge Handbook of Sport and Sustainable Development emphasizes that although elite athletes are supported by experts to improve their performance, their physical, social, and mental well-being must also be protected (McCullough et al., 2022). Regarding negative psychosocial issues, the authors highlight concerns such as controlling practices within close social environments, abuse, bullying, harassment, isolation, excessive expectations, psychological pressure, burnout, underperformance, and psychological maladaptation.

Szathmári and Kocsis (2020) defined sustainability in the context of elite sport as future-oriented rather than performance-oriented, and community-oriented rather than commodity-oriented, with the goal of promoting education and athletes’ well-being.

These perspectives lead to the concept of psychological sustainability in elite sport, which may be defined as the capacity of athletes to maintain mental well-being, cognitive functioning, emotional resilience, and performance adaptive functioning over time, particularly when facing environmental, social, training, and competitive stressors.

While psychological sustainability shares similarities with resilience and mental toughness, it is broader in scope. Resilience and toughness emphasize athletes’ capacity to cope with stressors, often in relation to performance outcomes. In contrast, psychological sustainability incorporates these adaptive qualities within the wider framework of sustainability science. It goes beyond coping and perseverance to encompass the long-term preservation of mental health, psychological well-being, and cognitive functioning. This perspective positions athletes not only as performers but also as sustainable individuals whose development should align with ethical, social, and organizational sustainability principles.

Existing literature has emphasized the importance of athletes’ personal development to manage the demands of sport and to maintain psychological well-being and mental health. The recent concept of inner sustainability (Jansen, 2024) contributes to clarifying the psychological empowerment process, which may be adapted to the sport context. Following Wamsler et al. (2021), inner sustainability includes five core internal transformative qualities: (1) connection to oneself, expressed through self-esteem, self-concept, and self-compassion—as well as connection to others and nature; (2) awareness, including self-awareness; (3) insight, referring to diverse modes of acquiring knowledge; (4) purpose, aligned with personal values; and (5) agency, which involves the skills necessary for effective interpersonal cooperation.

Although empirical studies on inner sustainability in elite sport are still limited, Jansen (2024) illustrates how these transformative qualities are linked to positive psychological adaptation in athletes and are supported by several methods in sport psychology. Additionally, based on current research, Jansen (2024) suggests that inner sustainability is associated with mental health and well-being, referring to the transformative qualities identified by Wamsler et al. (2021). The author further proposes that inner sustainability can be promoted through principles of positive psychology, including interventions such as self-compassion enhancement, mindfulness practices, and character strengths training, alongside traditional sport psychology techniques. In the same direction, Marín-González et al. (2024) concluded that tailored interventions aimed at improving athletes’ socio-emotional functioning are essential for supporting their psychological and social sustainability. Conversely, sport itself may foster the fulfillment of basic psychological needs that contribute to personal sustainable development.

However, the literature exploring the relationship between psychological sustainability—particularly from the perspectives of mental health and psychological well-being—and sports performance remains limited. Despite this gap, the International Olympic Committee has increasingly prioritized the mental health of elite athletes. This commitment is reflected in several key initiatives and publications, including the Mental Health in Elite Athletes: International Olympic Committee Consensus Statement (Reardon et al., 2019), the Mental Health in Elite Athletes Toolkit (IOC, 2021), the Mental Health Action Plan (IOC, 2023), and the recent announcement, New Measures in Place at Paris 2024 to Support Athlete Well-being (IOC, 2024). These initiatives incorporate core elements related to psychological sustainability, such as long-term mental health, resilience, and psychological well-being. They are consistent with the IOC’s broader strategy to support the mental and emotional resources of athletes, thereby promoting a more sustainable model for elite and Olympic sport.

Athlete well-being, as it relates to a sustainable approach, is also emphasized in the Olympism 365 portfolios, which adopt a rights-based framework. These programs are designed to prevent harassment and abuse while promoting the safety and well-being of all participants. Furthermore, they aim to ensure that opportunities are inclusive, accessible, non-discriminatory, and both environmentally and programmatically sustainable (Olympic Studies Centre, 2023).

3. A Sustainable Coaching Approach

The literature has reported that the path to high sports performance can pose significant risks to athletes’ physical and mental health and well-being, often influenced by a culture that overvalues success. For example, Barker et al. (2014) describe unethical, unhealthy, and illegal practices in various sports systems across Sweden, Germany, and Australia that contribute to unsustainable performance models. These include training systems that become debilitating, lead to burnout, promote the use of chemical substances, and involve both physical and psychological exploitation. Such systems frequently expose athletes to high stress levels that can result in emotional difficulties. Despite the negative impact on their health and well-being, many athletes remain in these systems, having been enculturated into them over time.

Furthermore, the prevailing culture of success pushes many athletes to pursue achievement during the limited period they can compete at the highest level. This is particularly evident in events such as the Olympic Games, where athletes have few opportunities to participate. The difference between earning a bronze medal and finishing just outside the podium can have profound consequences on an athlete’s career and personal life. Additionally, athletes must contend with other limiting factors, such as physical capabilities, psychological skills to manage pressure and stress, financial resources, and access to expert support. When the demands of high performance exceed the resources available to the athlete, the training environment becomes unsustainable.

3.1. Training Climate Management

Following the approach suggested by Rynne and Mallett (2014), a sustainable training system encompasses a set of environments and behaviours that efficiently and ethically utilise human and other resources, with the coach serving as a central and responsible figure. Accordingly, coaches must learn to manage ethical training programmes aimed at preparing athletes for top performance while preserving their physical and mental health.

Although it is beyond the scope of this article to study coaches’ emotions and behaviors in depth, the literature has demonstrated that coaches may be negatively affected by stressors, including sport-related ones such as performance outcomes, which in turn impact athletes’ emotions, thoughts, performance, and mental health. For example, while Olympic coaches perceived themselves as coping positively with stress related to Olympic participation, studies suggest that coaches may not be fully aware of their emotional expressions or may be unable to manage them effectively (Loftus et al., 2022; Thelwell et al., 2017). These authors concluded that top-level athletes could easily identify their coaches’ stress, which negatively affected their own emotions and confidence, and led to perceptions of a damaged coach-athlete relationship. As a result, the expression of coaches’ negative behaviours mostly impacts individual and team effectiveness, leading to dysfunctional performance; however, albeit less frequently, it may also lead to athletes’ positive reactions with a more goal-directed approach (Thelwell et al., 2017).

Dohlsten et al. (2020) highlighted athletes’ desire for athlete-centered coaching that extends beyond performance outcomes, emphasizing holistic development, shared decision-making, and the integration of sustainability topics into athlete preparation. This perspective is consistent with earlier findings by Dohlsten et al. (2018), who argued that elite sport coaches should balance performance enhancement with managing pressure and safeguarding well-being, thereby promoting coaching systems that are both effective and sustainable. In line with this view, Purdy et al. (2016) conceptualized caring coaching as a pedagogical climate in which coaches not only address athletes’ individual needs but also foster moral development. Furthermore, adverse life events and the absence of adequate support networks have been linked to anxiety and depression (Küttel & Larsen, 2019), underscoring the importance of social support. Taken together, these studies converge on the significance of holistic, athlete-centered approaches that prioritize personal development, health, and well-being. This integrative perspective emphasizes that sustainable elite sport requires coaches to support athletes’ growth as whole persons, often through collaboration with expert networks such as sport psychologists and mental health professionals, even though prevailing coaching practices may at times fall short of this ideal. Moreover, empathy, involving athletes and engaging in dialogue with them regarding coaching programmes and personal issues, despite the hard work towards competitiveness, communicates to athletes that they are perceived as human beings beyond their sports role (Annerstedt & Lindgren, 2014). Some studies suggest that caring coaching has a positive impact on elite and Olympic athletes, both in the psychological (Cook et al., 2020; Lindgren & Barker-Ruchti, 2017) and performance (Cook et al., 2020, 2021) dimensions.

Therefore, athlete-centered approaches align with psychological sustainability by balancing performance with athletes’ long-term well-being. By emphasizing co-creation, holistic development, and supportive climates, they address the immediate demands of competition while also preserving athletes’ mental health, resilience, and personal growth, thereby reducing risks such as burnout and anxiety.

Understanding and emotional awareness and management are considered determinants of coaching effectiveness, as concluded by Hodgson et al. (2017). Indeed, athletes’ psychological needs and burnout propensity are influenced by coaching styles based on autonomy-supportive approaches. Moreover, these are associated with higher levels of autonomy and competence, while coaching controlling styles promote lower levels of autonomy and relatedness (Isoard-Gautheur et al., 2012). Olympic athletes identified coaches who are self-focused, possess haughty self-belief, are inauthentic, manipulative, and success-obsessed as having negative effects on their confidence, pressure, and anxiety, but also stimulating positive reactions like motivation, resilience, and coping skills (Arnold et al., 2018).

On the other hand, Marín-González et al. (2024) suggest that Olympic and Paralympic athletes should follow specific psychological training programmes to enhance socio-emotional capacities within a sustainability-oriented coaching process, impacting behavioural efficiency. Regarding athletes’ mental health, Küttel and Larsen (2019), based on their scoping review, suggest that feelings of autonomy and positive relationships in sport and private life are potential protective factors.

Therefore, the concept of caring coaching, focused on a humanistic climate and pedagogy, is related to Goals 3 (Good Health and Well-being), 4 (Quality Education), and 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth) of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. In fact, the athlete-centered approach shows concern for the health and well-being of athletes, aligning with Goal 3. In order to achieve this goal, reflective practice should be promoted among coaches, encouraging them to consider the consequences of their actions on athletes’ feelings; elite athletes should be encouraged to provide systematic feedback on coaching styles, particularly regarding the impact on their psychological states; mental health education programs for coaches should be implemented, including training in mood observation. Goal 4 relates to supporting the personal development of athletes from a long-term perspective. In this regard, it is important to develop policies that promote Dual Career Programs, enabling elite athletes to pursue academic qualifications alongside their sports careers, including flexible schedules, tutoring, and academic scholarships, while elite coaches should be educated to support and encourage their athletes in engaging with these opportunities. Coaches should also play an active role in supporting athletes to go through structured exit pathways for life after sport, such as career counseling, professional retraining, or scholarships for further studies. Goal 8 is addressed through coaching practices that integrate technical–rational knowledge, appropriate control, instrumentality towards performance and respect for the athletes’ personal and professional development. For example, coaches should encourage discussions with athletes about both short- and long-term career pathways, including post-competition professional and personal development; foster inclusive, non-discriminatory working conditions; design individualized training schedules that accommodate education and employment opportunities; and advocate for fair and transparent contracts, prizes, and benefits for their athletes.

The management of the training/competitive process in elite sport, akin to human resources management in other professional fields, must consider the individual, the group (team), and the organization (club, federation, etc.), acting upon the working/training environment to promote athletes’ well-being and empowerment in pursuit of their psychological sustainability.

While unethical coaching practices have been acknowledged, a deeper examination of ethical dilemmas in elite sport highlights the conflict between the performance goals pursued by coaches and sports organizations and the well-being of athletes. In high-pressure contexts such as the Olympic Games, national federations and sponsors may prioritize medals and visibility over long-term health, leading to ethical compromises in which athlete welfare becomes secondary (McNamee, 2018). This can result in overtraining, the normalization of injury, and the silencing of mental health concerns—all of which run counter to the principles of caring coaching. Sustainable elite sport requires recognizing and actively managing these conflicts of interest. In practice, this means that coaches must embrace transparency, prioritize open dialogue, respect athletes’ autonomy, and adopt safeguarding behaviours that protect both physical and mental health.

3.2. Management of Training and Competition Psychological Load

Schubring and Thiel (2013) discussed the potential risks of intensive training, which may lead to growth issues in adolescent athletes. These issues are associated with a lack of well-being and the unsustainable development inherent in the organizational structures of high-performance sports. Additionally, Schwellnus et al. (2016) noted that death has been the ultimate consequence for some athletes due to excessively intensive training.

Furthermore, applied practice indicates that in the lead-up to major competitions, such as the Olympic Games, coaches often experience increased stress due to the uncertainty of competitive outcomes. To reduce this uncertainty, they may attempt to control the variables within their reach—namely, training intensity and pressure—potentially resulting in athlete overtraining.

From the perspective of psychological sustainability, the planning and management of training and competition must adhere to principles that preserve mental health, support adaptive functioning, and prevent burnout (Di Fabio & Rosen, 2018). Both physical and psychological exertion contribute to the overall fatigue experienced by athletes, which can lead to non-functional overreaching due to psychological and hormonal alterations (Kellmann et al., 2018). This, in turn, negatively affects both performance and physical and mental health.

For example, mental fatigue may arise from extended periods of intense training and competition that demand high cognitive effort. It can also result from repetitive and monotonous activities such as unvaried training routines or excessive performance analysis (Roelands et al., 2022; Pageaux & Lepers, 2018). Additionally, pressure from coaches or organizational expectations (Cho et al., 2019; Thelwell et al., 2017), along with frequent travel, may contribute to cognitive and emotional disturbances in athletes (Doherty et al., 2023).

Research has also identified various psychological symptoms in elite athletes linked to periods of intense training. These include mood disturbances—such as increased tension and fatigue, and reduced vigor (Selmi et al., 2020; Garatachea et al., 2012)—as well as psychological fluctuations throughout the sports season (Russell et al., 2021). Moreover, insufficient management of training load may reduce the ability to recover from stress (Stephenson et al., 2018). Therefore, coaches and sport practitioners should systematically monitor mental fatigue alongside physical fatigue, particularly during intensified training or competition periods, such as the pre-Olympic preparation phases, as supported by the reviewed literature.

Moreover, certain training-related factors and competitive stress appear to be predictive of anxiety and depression among elite athletes involved in high-pressure sports. Musculoskeletal injuries have been linked to an increased risk of anxiety and depression (Kilic et al., 2017; Gouttebarge et al., 2019), as have chronic stress, negative stress–recovery states, and overtraining (Rice et al., 2019; Nixdorf et al., 2013).

Regarding elite athletes preparing for the Olympic Games, Drew et al. (2017) found a high incidence of illness symptoms during the three months leading up to the Games, which was associated with a combination of anxiety and adverse stress–recovery states. The authors emphasize the need for a multidisciplinary approach in preparing Olympic athletes.

Additionally, the International Olympic Committee’s consensus statement on load in sport and the risk of illness (Schwellnus et al., 2016) highlights the importance of psychological load management in elite athletes’ preparation. This includes reducing stress factors and training/competition loads, as well as implementing stress assessments to monitor and adjust these loads appropriately. To achieve this, the authors advocate for the development of literacy programs for both athletes and coaches, aimed at helping them recognize athletes’ responses to the training/competitive process and understand these reactions to make appropriate adjustments.

Several validated tools have been developed to monitor fatigue and overtraining. For example, the Recovery–Stress Questionnaire for Athletes (RESTQ-Sport) provides detailed insights into maladaptation during heavy training phases (Heidari & Kellmann, 2023; Kellmann & Kallus, 2001). Similarly, the Daily Analysis of Life Demands for Athletes (DALDA) distinguishes between sources and symptoms of stress and can serve as an early warning indicator of insufficient recovery (Wang et al., 2023). The session-RPE method, which multiplies athletes’ perceived exertion by training duration, has also been validated as a reliable measure of internal training load (Haddad et al., 2017). When combined with the Profile of Mood States (POMS), session-RPE has shown sensitivity to training-induced fatigue (Comotto et al., 2015). Incorporating these tools into a sustainability framework allows coaches to detect early signs of non-functional overreaching, make timely training adjustments, and safeguard athletes’ long-term health and performance.

3.3. Athletes’ Psychological Resources Enhancement

Although training and competition loads must be properly managed to protect athletes’ well-being, mental health, and performance capacity, providing athletes with psychological resources is also an essential component of psychological sustainability in elite sport. Teaching and training psychological coping techniques can benefit athletes by enhancing both mental health and performance. For example, Nixdorf et al. (2013) suggest that maladaptive coping strategies are associated with depression, while Myall et al. (2021) found that mindfulness skills serve as protective factors against depression and anxiety. In this context, Schwellnus et al. (2016) recommend that athletes be educated in stress management strategies, confidence building, and goal setting to minimize the effects of stress and reduce the likelihood of illness during intense and stressful training/competitive periods.

In their review of mental toughness and mental health in elite sport, Gucciardi et al. (2017) emphasize the importance of achieving an optimal balance between preventing ill-health and promoting health and performance. They note that evidence suggests mental toughness may be indicative of mental health. Moreover, the authors argue that athletes and coaches may be more receptive to mental training programs that promote mental health when these are framed as methods for enhancing mental toughness, a concept more readily associated with sport performance than with mental health challenges.

Although definitions of mental toughness vary across authors, it can be generally understood as a psychological resource encompassing cognitive, emotional, and behavioral components that enable individuals to persist in goal-directed behavior despite significant obstacles and stressful situations. Various methods have been used to enhance athletes’ mental toughness (Stamatis et al., 2020; Corrêa et al., 2023), and the literature reflects multiple perspectives on the components of this concept. In their review, Corrêa et al. (2023) observed that interventions targeting psychological skills—such as self-confidence, concentration, and self-regulation—aimed at developing mental toughness often employed traditional strategies including self-talk, visualization, relaxation, thought control, and personal routines. The authors concluded that approaches to developing mental toughness align closely with traditional psychological skills training in terms of both the competencies targeted and the techniques employed. Applied studies have also explored sport-specific approaches to psychological training, highlighting their relevance for enhancing skills and well-being under competitive pressure (e.g., Al-Fraidawi et al., 2025).

Behnke et al. (2017) propose that mental training consists of mental skills and mental techniques, building on Birrer and Morgan’s (2010) distinction between psychological skills—defined as learned capacities to perform specific tasks—and psychological techniques, which are the methods used to develop and enhance those skills. The authors identify imagery, goal-setting, self-talk, and relaxation as the four fundamental psychological techniques and define psychological strategies as action plans designed to develop psychological skills through the use of one or more techniques.

Based on their development of the Sport Mental Training Questionnaire, Behnke et al. (2017) categorize mental skills into three domains: (i) foundation skills, described as in-trapersonal resources including self-confidence, self-awareness, and perseverance; (ii) performance skills, defined as mental abilities essential to execution that involve cognitive, emotional, physical, and behavioral regulation; and (iii) interpersonal skills, referring to the ability to interact and communicate effectively with others. In contrast, mental techniques include (i) self-talk, or the use of internal dialogue to focus attention and regulate thoughts, emotions, and arousal; and (ii) mental imagery, which involves using internal images and scenarios to manage emotions and prepare for performance. Their findings indicate that self-talk and imagery are the most commonly used mental techniques among athletes and that expert athletes demonstrate significantly higher mental training skills and technique use compared to lower-level athletes. Moreover, the literature indicates a close interrelationship between mental health and sport performance (Durand-Bush et al., 2022; Gucciardi et al., 2017; Schwellnus et al., 2016). This is particularly relevant in Olympic preparation, where sustainability principles require the simultaneous enhancement of performance capacities and the preservation of athletes’ long-term psychological well-being.

The psychological demands of sport-specific tasks and performance contexts require athletes to possess corresponding mental resources. Consequently, psychological training programs must be tailored to these specific needs to equip athletes with the appropriate skills. In preparation for the Olympic Games, consideration must be given not only to the characteristics of each sport but also to the unique demands of the Olympic context.

In a foundational study, Gould et al. (2002) identified key psychological characteristics of American Olympic champions, including anxiety coping and control, confidence, mental toughness/resilience, sport intelligence, the ability to focus and block distractions, competitiveness, a strong work ethic, goal-setting and achievement, coachability, dispositional hope, optimism, and adaptive perfectionism. Similarly, Fletcher and Sarkar (2012), in their study of Olympic champions, concluded that psychological attributes such as a positive personality, motivation, confidence, focus, and perceived social support contributed to resilience and protected athletes from the negative effects of stress. In sport, resilience may be defined as a dynamic process through which athletes employ cognitive and behavioral strategies to develop personal strengths and mitigate the impact of competitive stressors and adversity.

The Gold Medal Profile for Sport Psychology (GMP-SP), proposed by Durand-Bush et al. (2022), is a recent evidence-informed framework that outlines mental performance competencies associated with elite sport success and makes it possible to reach the Olympic and Paralympic podiums. Developed based on the experiences of top Canadian athletes, the GMP-SP identifies 11 mental performance competencies grouped into three categories: (i) fundamental competencies, including motivation, confidence, and resilience; (ii) self-regulation competencies, including self-awareness, stress management, emotional and arousal regulation, and attentional control; and (iii) interpersonal competencies, including the athlete-coach relationship, leadership, teamwork, and communication. Mental health is also integrated into the model as a foundational construct that interacts with and supports all three dimensions of performance.

Overall, the psychological skills and competencies described by the aforementioned authors share considerable overlap, though they may be labeled differently across frameworks. Notably, Behnke et al. (2017), Birrer and Morgan (2010), and Corrêa et al. (2023) consistently distinguish between mental skills and mental techniques, clarifying that specific methods are used to develop particular psychological capabilities.

3.4. In Summary

- Aligned with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, sustainable sports training is founded on environments and behaviors that utilize human and other resources efficiently and ethically. The pursuit of high performance must be integrated with the preservation of athletes’ physical and mental health.

- In line with the International Olympic Committee’s perspectives on mental health and well-being, psychological sustainability must be incorporated into the elite sustainable training system. This refers to athletes’ capacity to maintain mental well-being, cognitive functioning, emotional resilience, and adaptive performance functioning over time—particularly in response to environmental, social, training, and competitive stressors.

- To promote a psychologically sustainable approach within elite sport training systems:

- A coaching climate should be fostered that is athlete-centered, focused on holistic development, and emphasizes the co-creation of the athlete’s overall growth. Within this framework, performance enhancement needs must be balanced with managing high-pressure environments and supporting athlete well-being.

- The recommendations outlined in the IOC consensus statement on load in sport and risk of illness (Schwellnus et al., 2016) should be implemented, specifically those concerning the management of psychological load in elite athletes’ sport preparation. This includes reducing stressors and regulating training and competition loads.

- Athletes’ psychological resources and skills should be systematically developed to enhance their ability to cope with the demands of elite sport. This can be achieved through the use of evidence-based psychological techniques that are taught and practiced as part of the broader sports preparation process.

4. Towards a Model of Psychologically Sustainable Sport Training

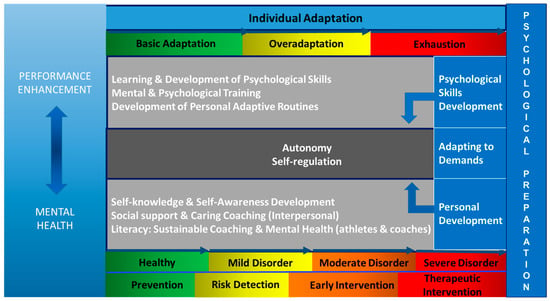

The concept of positive balance, which underpins athletes’ psychological adaptation to the demands required for elite-level performance and the psychological resources necessary to meet those demands, forms the foundation of the model of psychologically sustainable sport training (see Figure 1). The interrelationship between performance enhancement and mental health supports a psychological preparation approach in which the development of psychological skills and personal development strategies fosters athletes’ autonomy and self-regulation under sport-related pressures and stress, enabling high achievement while preserving mental well-being.

Figure 1.

Model of Psychological Sustainability in Sports Training.

Elite sport training is aimed at developing athletes’ capacity for high performance by stimulating progressive neurological, physiological, and psychological adaptation through planned, systematic, and scientifically grounded methods. Individual training load management is a critical element of this process: if the load is too low, no adaptation occurs; if it is too high and exceeds the athlete’s capacity, it may result in performance decline and compromise both physical and mental health. Therefore, psychological load, like physical load, must be carefully managed. Athletes must also be equipped with psychological resources to cope with the demands of high-performance sport (Schwellnus et al., 2016; Schubring & Thiel, 2013).

Additionally, athletes’ mental health may deteriorate in response to excessive psychological demands related to training and competition. This highlights the importance of monitoring the evolution of athletes’ mental health and responding to their needs—an effort that relies heavily on coaches’ mental health literacy. Furthermore, athletes themselves should be educated to recognize early signs of psychological distress or mental health issues.

The top section of Figure 1 illustrates the athlete’s progressive individual adaptation to increasing pressures and performance demands. The left column highlights the integration of performance enhancement with athletes’ mental health status. The bottom section of the model represents the mental health dimension of elite sports participation. While athletes are generally expected to be mentally healthy, they may experience a range of mental disorders, from mild to severe, due to personal, sport-related, or external factors.

This reality underscores the necessity for both coaching staff and athletes to be capable of recognizing early symptoms of mental health concerns and to act swiftly and appropriately. Beyond reactive measures, mental health promotion must also include proactive strategies such as sound training design and the implementation of preventive psychological interventions.

Hardy et al. (1996) developed the concept of psychological preparation as the process of readying an athlete’s cognitions and emotions for a specific situation, competition, or task through the use of strategies aimed at optimizing psychological states and performance. As discussed previously, psychological preparation also contributes to the maintenance and enhancement of athletes’ mental health (Corrêa et al., 2023; Gucciardi et al., 2017; Myall et al., 2021).

The right column of Figure 1 (Psychological Preparation) illustrates how psychological preparation encompasses strategies that address both performance enhancement and mental health care. This includes the Psychological Skills Development component, which refers to coaching programs designed to educate athletes about psychological skills. These programs involve targeted psychological and mental training adapted to the characteristics of the athlete, sport, and context, and support the development of individualized coping routines (Behnke et al., 2017; Birrer & Morgan, 2010; Durand-Bush et al., 2022).

Psychological training is defined as a repetitive, systematic, planned, and multidimensional process designed to stimulate psychological skills using psychological techniques that support adaptability and improve performance (Serpa, 2017). Mental training, on the other hand, involves the planned, repeated, and conscious use of imagery focused on motor skills, sport techniques, strategies, tactics, and overall performance in sport contexts (Samulski, 2002).

The Personal Development component of psychological preparation concerns the athlete’s self-knowledge and self-awareness in relation to the transformative qualities encompassed within inner sustainability (Jansen, 2024). It involves interpersonal strategies that promote social support and caring coaching (Dohlsten et al., 2020; Purdy et al., 2016). This dimension should be grounded in educational programs for both coaches and athletes that focus on sustainable coaching and mental health, enabling them to recognize and appropriately respond to athletes’ psychological cues (Gorczynski et al., 2019; Gorczynski et al., 2020; Schwellnus et al., 2016).

Finally, the Adapting to Demands component refers to the athlete’s autonomy in facing sport-specific challenges and their self-regulation capacities. These capacities are fostered through the techniques and strategies linked to both psychological skills development and personal growth (Behnke et al., 2017; Birrer & Morgan, 2010; Durand-Bush et al., 2022; Isoard-Gautheur et al., 2012; Küttel & Larsen, 2019).

The Gold Medal Profile for Sport Psychology (GMP-SP) provides a framework of mental performance competencies based on analyses of top-level athletes’ characteristics, with mental health serving as a foundational dimension that supports performance. However, it does not specify how these two aspects can be developed in a coordinated manner. On the other hand, the IOC consensus adopts a clinical perspective, highlighting mental health as a global priority and offering guidelines and action plans to protect athletes from illness, burnout, and maladaptation through systemic policies and load management. Yet, it places less emphasis on the psychological aspects of performance enhancement. The Model of Psychologically Sustainable Sport Training (MPSST) contributes a new perspective by integrating performance enhancement with psychological sustainability, positioning mental health not merely as a protective factor but as an interdependent component of training itself. Its originality lies in conceptualizing psychological preparation as a sustainability process—embedding psychological skills training, personal development, and adaptive regulation into the very structure of sport psychological preparation, together with mental health protecting components. Thus, while the GMP-SP and IOC frameworks emphasize competencies and protective measures, the MPSST introduces a holistic, ecological paradigm in which performance and mental health are co-developed, making it a distinctive and forward-looking contribution. The MPSST is a theoretically grounded framework that integrates existing theories, research findings, and expert knowledge into a structured representation of how key constructs relate to one another. Its aim is to bridge sustainability science, coaching, and mental health—domains that have not yet been thoroughly integrated empirically—thereby enabling both scientific advancement and applied innovation even before sufficient empirical evidence is available. It offers an integrative lens for capturing the interdependence of these dimensions and ultimately serves as a roadmap for designing interventions and guiding future empirical testing. Crucially, it acknowledges that the relentless pursuit of excellence, which drives athletes and coaches alike, inevitably affects athletes’ mental health. Therefore, psychological training methods must safeguard both performance and well-being.

5. The Olympic Preparation from the Perspective of Psychological Sustainability

The Olympic competition, the Village environment, and the months leading up to the Games place significant psychological demands on athletes, necessitating the efficient use of their psychological resources.

A psychological sustainability approach should be adopted in athletes’ Olympic preparation to pursue performance enhancement while safeguarding mental health. Ac-accordingly, literacy programs should be developed not only for coaches and athletes but also for sport managers, who must receive adequate education on these issues. In fact, research findings suggest that the knowledge thus gained increases coaches’ confidence about the symptoms of the most common mental health disorders and their confidence in helping athletes (Sebbens et al., 2016), as well as reduces athletes’ stigma about mental health issues, making them more aware and encouraging them to seek help when they feel the need (Daley et al., 2023). Programs related to psychological preparation for the Olympic Games should incorporate strategies and tools that are generally part of elite athletes’ preparation. However, it is important to note that while the performance demands and technical requirements are not fundamentally different from other high-level competitions, the context of the Olympic Games presents unique psychological challenges (Anderson, 2012; Arnold & Sarkar, 2015; Gould & Maynard, 2009). The Olympic context creates a distinct climate and set of demands that begin well before the Games themselves. Moreover, the “mystique” of the Games lends them a strong symbolic meaning for both athletes and coaches, resulting in intense emotional experiences that may have medium- and long-term consequences—either positive or negative—for psychological well-being and mental health.

Educational programs for coaches should aim to provide knowledge about mental health, sustainable coaching practices, and psychological skills training. These should include basic techniques that coaches can incorporate into their training programs, as well as principles of careful coaching. While an in-depth discussion of these topics falls outside the scope of this article, extensive literature is available. Beyond foundational training in psychological skills and tools, mental health literacy will enable coaches to recognize behavioural and emotional changes in their athletes that may indicate psychological problems. Coaches must also understand how to respond appropriately and when to seek professional psychological support.

The specific context of Olympic preparation and the Olympic Games themselves must be taken into account, given the heightened psychological pressure, potential for over-training, and the presence of multiple distractions during both the preparation and competition phases. Additionally, coaches must be aware of their own psychological responses and emotional vulnerabilities, including the risk of unintentionally transferring their anxiety to athletes—particularly in a setting where athletes’ performance may significantly impact the coaches’ own professional reputations.

Educational initiatives could include lectures, practical workshops, case studies, short videos or podcasts, and other interactive formats, such as peer discussions. These formats can be enriched by the experiences of those who have participated in previous Olympic Games, offering valuable insights to less experienced coaches.

Literacy programs for athletes should aim to enhance their understanding of mental health in the context of elite sport. These programs should also help athletes identify personal “yellow flags” (early warning signs) and “red flags” (critical signs) in their behaviours and mental states, and support the reduction in stigma associated with seeking professional psychological help. Furthermore, athletes should be educated on the role of psychological techniques in both enhancing psychological skills and protecting mental well-being.

Practical sessions and workshops on psychological techniques can serve as motivational tools, encouraging athletes to systematically incorporate psychological training into their overall sport preparation. These applied formats can foster engagement and normalize the integration of mental training within physical and technical training regimens.

As international qualifying competitions for the Olympic Games and national trials approach, psychological stressors typically intensify. Athletes who have received psychological education are better equipped to understand their emotional and cognitive responses during these high-pressure periods. Moreover, by experiencing and practicing various emotional regulation techniques throughout the Olympic cycle, they are more likely to identify and consistently use those that align with their individual needs and sport-specific demands.

Although organizational systems may vary across countries, sports organizations play a central role in promoting the psychological sustainability of their athletes. Therefore, specific actions should be incorporated into their programs. Ethical codes designed to prevent mental health problems in performance-enhancing contexts should be developed, along with follow-up measures to ensure compliance and to counter the prevailing win-at-all-costs mentality. Monitoring athletes’ psychological well-being and mental health must go hand in hand with tracking their sporting performance, while maintaining and respecting the balance between training and recovery. In some cases, ‘mind rooms’ have been established (DeMichelis, 2007), such as in the Paris 2024 Olympic Village, where athletes could access relaxing environments and, at times, bio/neurofeedback tools. Specific protocols should also be developed to guide responses when signs of psychological distress are detected, whether by coaching staff or mental health professionals working in close collaboration. Furthermore, organizations should implement literacy programs for both coaches and athletes, using strategies and tools adapted to their specific contexts. Coaches must also receive regular updates on best practices that integrate performance enhancement with mental health protection.

Olympic Games and Psychological Preparation

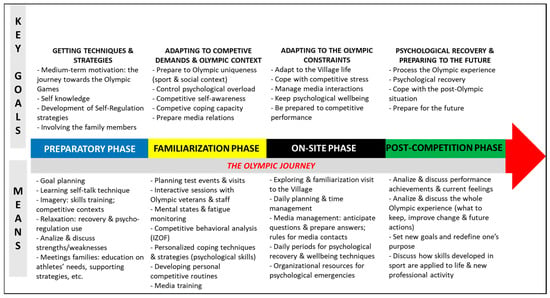

Psychological preparation for the Olympic Games must begin several years in advance (e.g., Arnold & Sarkar, 2015; Lidor & Blumenstein, 2009) and should be structured into four key phases: the preparatory phase, the familiarization phase, the on-site phase, and the post-competition phase (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The Olympic Journey: goals & operational means.

The preparatory phase begins when participation in the Olympic Games becomes a realistic goal for the athlete. During this stage, Olympic objectives are set, skill development is improved, and specific performance targets are identified. Athletes participate in numerous competitions, which serve as opportunities to test and refine psychological strategies and incorporate them into their competitive routines. This phase also includes participation in Olympic qualifying events and the development of a targeted preparation plan that considers the athlete’s individual characteristics, experience, and the specific demands of their sport.

Throughout the preparatory phase, psychological skills should be systematically introduced and trained. Athletes develop personalized adaptive routines and long-term psychological strategies. It may also be beneficial to involve the athletes’ families in this phase. Educating family members about the psychological demands of elite sport can help them recognize behavioural or emotional signs of distress in the athlete, and encourage timely professional support if necessary. Assisting the families in supporting the athletes’ needs can be a valuable resource as well.

The familiarization phase begins weeks or months prior to the Games, depending on when the athlete qualifies. During this phase, preparation focuses on the unique characteristics of the Olympic environment. Competition strategies are finalized, and both physical and psychological training loads should be carefully managed. Whenever possible, athletes should be exposed to the Olympic venues, the Olympic Village, and the host city to foster environmental familiarity. Ideally, this involves attending test events at the competition venues. If in-person visits are not feasible, videos, photographs, and other media resources should be used to support acclimatization.

Additionally, athletes must be prepared for the distinctive social experience of the Olympic Games, which can contribute to cognitive and emotional dysregulation, especially for first-time Olympians. To address this, group sessions that include veteran Olympians can be valuable in preparing rookies for the emotional and social dynamics of Olympic participation.

The increased number of international competitions in the year preceding the Olympic Games—including events hosted at Olympic venues—appears to influence Olympic performance outcomes. However, during the final months before the Games, athletes are particularly susceptible to overtraining, which necessitates careful monitoring of their psychological well-being.

Special attention should be paid to selection procedures. A lack of transparency or delayed decision-making can lead to insecurity among athletes, heighten anxiety, and complicate the management of expectations, goals, and training plans. Furthermore, athletes must be prepared for the unusual intensity of media interactions, especially considering that media attention in many sports is limited to the Olympic season. Athletes’ lack of experience with the media can increase anxiety and result in the communication of inappropriate or damaging messages, which may negatively affect their public image. Therefore, media training should be incorporated into psychological preparation programs.

The on-site phase, beginning upon arrival at the Olympic Village, requires meticulous planning (Blumenstein & Lidor, 2008; Collins & Cruickshank, 2014). This phase includes both the pre-competition and competition periods. Athletes must cognitively, emotionally, and behaviourally adjust to the Olympic environment. As early as possible, it is advisable for both athletes and staff to take an exploratory tour of the Olympic Village, familiarizing themselves with essential locations such as training and competition venues, transportation centres, restaurants, social spaces, laundry services, and medical support areas. Daily planning—including detailed itineraries for competition days—can help stabilize emotions and reduce stress.

Many athletes place excessive emphasis on performance outcomes, which can result in an imbalance between their sporting goals and the enjoyment of the Olympic experience. Athletes should be encouraged and prepared in advance to appreciate the opportunity to be among the world’s elite, recognizing their journey and dedication. Simultaneously, they must maintain the discipline required to achieve their athletic objectives. Additionally, athletes must be prepared to manage substantial amounts of potentially anxiety-inducing free time. Learning to structure and purposefully use this downtime can support anxiety regulation and reduce intrusive thoughts.

Media relations must be carefully managed, particularly with regard to the timing of interviews and allowing athletes the space to regulate their emotions beforehand. Helping athletes anticipate potential interview questions and develop prepared responses can foster confidence and composure. Furthermore, athletes should be coached in how to manage their social media use—including when and how long to engage, and for what purposes.

At the psychosocial level, the stress of the Olympic context and, in some cases, unresolved interpersonal issues, may contribute to a tense team climate. Coaches must rely on their own emotional self-regulation, uphold pre-established group norms, and facilitate open, constructive communication to maintain a supportive environment.

The post-competition phase, following the conclusion of the Games, can be psychologically challenging for many athletes. Coping with unfulfilled personal or public expectations, the pressures of sudden success, or the end of an athletic career may place significant demands on an athlete’s psychological resources. The psychological impact of the Olympic experience may endure for years and can manifest as emotional distress or mental health disorders, ranging from mild to severe. This phase should focus on processing the Olympic experience, fostering emotional resolution, promoting personal growth, and preparing for the future—both within sport and beyond. Setting new goals and redefining one’s purpose are essential steps in transitioning meaningfully into the next phase of life or athletic endeavor.

Although it is not within the scope of this paragraph to detail the specific preparation required for all sports, contexts, and situations, it is important to note that these factors should be considered in planning and interventions related to Olympic preparation. Different types of sports require distinct psychological procedures: (i) Self-paced sports (e.g., artistic gymnastics, figure skating) involve closed, controllable, routine, and individualized tasks that carry a high risk of frustration, highlighting the need for emotional stability, concentration techniques, and pre-performance routines. (ii) Direct confrontation sports (e.g., fencing, judo) involve open, reactive, and anticipatory tasks, with irregular outcome patterns under time and result pressure. These characteristics increase frustration risk and demand training in externally directed attention, decision-making, and emotional regulation in response to situational changes. (iii) Endurance-based sports (e.g., rowing, middle- and long-distance running) involve alternating closed and open tasks with high fatigue potential, requiring athletes to develop persistence, strategies for managing physical discomfort, attentional control (associative/dissociative strategies), and in-competition goal management. (iv) Team sports share features of the above categories (e.g., self-paced in penalty kicks, direct confrontation when reacting to opponents, endurance when playing extra time in a very intense match). Their defining feature, however, is interdependence, making group dynamics—particularly cooperation and leadership development—central to preparation.

Athletes’ maturity and Olympic experience also influence psychological preparation. Younger athletes typically possess fewer coping resources and may be more vulnerable to the pre-Olympic and Olympic context, requiring particular support from coaches and psychologists. Also, first-time Olympians, lacking personal reference points, should receive preparatory guidance to anticipate the Olympic environment. Conversely, experienced Olympians may face pressure to achieve success due to expectations tied to their veteran status, which requires careful psychological management.

Other contextual factors also shape preparation. These include cultural attitudes toward competition and national representation (e.g., Si et al., 2015) and phenomena such as home disadvantage (McEwan & Hoffmann, 2021), as observed in the Brazilian soccer team’s 1–7 loss to Germany in the 2014 World Cup semifinal. Finally, resource availability plays a crucial role, particularly in access to technologies such as bio/neurofeedback (Blumenstein & Orbach, 2018) or virtual reality training (Gonzalez-Fernandes et al., 2025), as well as in providing designated areas for psychological support, which at Olympic venues are often improvised and adapted.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

Aligned with the United Nations’ 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, scientific literature has increasingly addressed the concept of a science of sustainability from a transdisciplinary perspective—integrating fields such as sport, coaching, and psychology. Within the domain of sport psychology, a sustainability-oriented approach aims to preserve and enhance athletes’ psychological well-being and mental health in competitive contexts, where the pursuit of high performance often pushes the limits of internal resources.

Psychological robustization, therefore, is part of the endosustainable process of achieving excellence (Triantafyllidis & Mallen, 2022) and contributes to athletes’ anti-fragility—their ability to grow stronger through stressors (Taleb, 2012). This must be accompanied by the appropriate management of training, competition, and contextual demands relative to athletes’ adaptive capacities, aligning with the concept of organizational sustainability (Di Fabio & Svicher, 2021; Ehnert, 2009).

The science of sustainability is inherently action-oriented, promoting attitudes and behaviours that prevent the imbalance between existing resources and their exploitation in a way that jeopardises human well-being and survival. In the context of sports psychology, a sustainable approach to Olympic preparation integrates tools, strategies, and methods traditionally used in elite sport psychology, with the goal of preserving athletes’ mental well-being, cognitive functioning, and emotional resilience. This approach supports athletes’ capacity for performance adaptive functioning over time, despite exposure to environmental, social, training, and competitive stressors—each of which has unique implications within the Olympic context. Such an approach is also consistent with the International Olympic Committee’s recommendations regarding sustainable sport, psychological well-being, and mental health.

The model of psychologically sustainable sport training emphasizes the use of psychological techniques and strategies to foster both performance-related skills and personal development. These elements contribute to athletes’ autonomy and self-regulation—capacities essential for optimizing performance while safeguarding mental health.

It is widely recognized that the Olympic Games are a singular event that imposes unique adaptive demands beginning as soon as qualification becomes a tangible goal. The Games carry profound personal and social meaning, prompting extraordinary commitment from athletes as they confront internal pressures and external expectations that can exceed their coping capacities.

In this sustainable framework, psychological preparation for the Olympic Games must be planned across multiple phases and dimensions, tailored to athletes’ personal characteristics and the specific demands of their sport.

The preparatory phase begins years in advance, once the Olympics are embraced as a concrete objective. A foundational component of this phase is the promotion of mental health literacy for both coaches and athletes, and the education of coaches in sustainable coaching practices. Practical implementation includes teaching psychological techniques, allowing athletes to experiment with and adopt those best suited to their needs, and integrating them into their training programs to support both performance enhancement and mental health preservation.

The familiarisation phase begins when athletes officially qualify for the Games. During this period, psychological strategies are used to help athletes become acquainted with the Olympic context and venues, and to deepen their self-regulation skills in anticipation of the unique stressors they will face.

The on-site phase encompasses the entire period athletes spend at the Olympic venue. This phase aims to promote optimal emotional and cognitive adaptation, as well as behavioural adjustment, in preparation for and during competition.

The post-competition phase addresses the period following the Games and seeks to support athletes in processing their Olympic experience. This includes coping with potential emotional challenges related to performance outcomes and their subsequent impact on athletes’ mental health and social identities.

Elite and Olympic sport represents the pinnacle of competitive sports development and athletes’ careers. Over the years, the formation process of athletes has shaped their physical, technical, psychological, moral, and ethical dimensions. Young athletes are directly influenced by their coaches and families, while sport managers and policymakers exert indirect influence through the structures in which athletes train and compete, as well as through implicit and explicit messages conveyed in speeches and policies. By the time athletes reach the elite and Olympic level, much of the physical, psychological, and cultural foundation is already established, enabling the application of high-performance training methodologies, including psychologically sustainable approaches. Thus, athletes’ acceptance of and commitment to such methodologies vary, which poses an important challenge for their development. Some may have been raised within a sustainability-oriented sport framework, with prior experience in psychological processes that support both sport and personal growth, and may already value the preservation of mental and physical health alongside sporting success. These athletes tend to adapt more readily to sustainable approaches. In contrast, others may hold reactive attitudes, associate stigma with psychological support, and therefore resist such methods, making their implementation more difficult.

Moreover, elite sport—including the Olympic Games—has become highly commercialized, drifting away from the original ideal of “mens sana in corpore sano”, in which sport was valued as a means of character building, moral education, physical development, and health promotion. Today, elite athletes often become commodified as economic products and generators of parallel commercial activities. Priorities include attracting paying spectators at venues and via broadcasts, driving demand for equipment and merchandise, and stimulating secondary businesses. Consequently, many athletes become acculturated into a commodified sporting environment characterized by excessive demands on health, reliance on artificial enhancement, and the prioritization of entertainment value. This environment frequently pressures athletes to prioritize results at the expense of their long-term health and well-being.

Implementing a psychologically sustainable model of sport training for Olympic preparation and post-Olympic participation requires addressing multiple factors. Institutional approaches often emphasize performance outcomes and medal counts over athlete well-being, undervaluing psychological services and perceiving mental training as secondary to biomechanics, nutrition, or medical support. This is exacerbated by stigma around psychology and mental health. In many cultural contexts, open discussion of psychological difficulties is discouraged, and athletes may fear being perceived as weak if they seek help. To counter this, psychological training should be framed not merely as mental health support but as a tool to enhance focus, resilience, and recovery. Empirical evidence and success stories—such as Olympic champions crediting mental skills training for their achievements—can demonstrate its performance benefits. Workshops and literacy programs for athletes, coaches, and staff should also be implemented, while psychological evaluation and monitoring should become as routine as physical assessments. Presenting mental strategies as methods for strengthening capacity, rather than fixing weakness, can help normalize their role. Progressively, such approaches will position performance training and mental health protection as inseparable components.

The undervaluation of psychological support can also lead to budgetary constraints in Olympic preparation, where funding often prioritizes physical training, equipment, facilities, or travel, while psychological services are treated as optional extras. This frequently results in sporadic or reactive interventions, mostly during crises. To address this, evidence should be presented showing how psychological care reduces risks such as injury, burnout, dropout, and team conflict, ultimately saving costs in the long term. Depending on national systems, sustained funding programs could be established through collaboration among state organizations, Olympic committees, private sponsors, and health institutions. Partnerships with universities and research centers can also provide scientific support for elite athletes.

Resistance to psychological training often stems from athletes’ lack of early preparation and consistent skill development throughout their careers. Too often, interventions are sporadic, last-minute, or crisis-driven rather than embedded in long-term, structured development, leading to limited effectiveness. To avoid this, psychological techniques should be integrated consistently from the early stages of sports careers or, at least, of the Olympic cycle.

Finally, psychological staff are often isolated from coaches, medical teams, or performance directors, resulting in weak communication channels that hinder both multidisciplinary teamwork and athletes’ perception of psychological services. Coaches may also resist collaboration due to concerns that psychologists could interfere with their authority. To overcome these barriers, psychologists should be embedded within daily training environments, work in close communication with coaches, physiotherapists, nutritionists, and medical staff, and adopt shared language and collaborative planning. This ensures that psychological preparation is aligned with physical, technical, and tactical training.

In summary, the psychological sustainability of Olympic sport preparation and training aims to support athletes in upholding the essential principle of high-performance sport—the continuous pursuit of excellence—while simultaneously preserving mental health as a core and inalienable foundation of athletic participation, which needs to be prepared and implemented at various levels.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Al-Fraidawi, H. S. H., Zahedi, H., Yasser, Elioudeh, A. M., & Meshkati, Z. (2025). Comparison of the effects of a training period with sports vision, specialized, and combined approaches on certain skill components and mood in young iraqi volleyball players under psychological pressure. International Journal of Sport Studies for Health, 8(1), 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R. (2012). Faster, higher, psychologically stronger: Sport psychology at the London Olympic Games. InPsych, 34(6). Available online: https://psychology.org.au/publications/inpsych/2012/dec/anderson (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Annerstedt, C., & Lindgren, E. C. (2014). Caring as an important foundation in coaching for social sustainability: A case study of a successful Swedish coach in high-performance sport. Reflective Practice, 15(1), 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, R., Fletcher, D., & Hobson, J. (2018). Performance leadership and management in elite sport: A black and white issue or different shades of grey? Journal of Sport Management, 32(2), 452–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, R., & Sarkar, M. (2015). Preparing athletes and teams for the Olympic Games: Experiences and lessons learned from the world’s best sport psychologists. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 13(1), 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, D., Barker-Ruchti, N., Wals, A., & Tinning, R. (2014). High performance sport and sustainability: A contradiction of terms? Reflective Practice, 15(1), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behnke, M., Tomczak, M., Kaczmarek, L. D., Komar, M., & Gracz, J. (2017). The sport mental training questionnaire: Development and validation. Current Psychology, 38(2), 504–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birrer, D., & Morgan, G. (2010). Psychological skills training as a way to enhance an athlete’s performance in high-intensity sports. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports, 20(s2), 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumenstein, B., & Lidor, R. (2008). Psychological preparation in the Olympic village: A four-phase approach. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 6(3), 287–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumenstein, B., & Orbach, I. (2018). Periodization of biofeedback training: New trends in athletic preparation. In F. Chiappelli (Ed.), Advances in psychobiology (pp. 49–62). Nova Science Publisher. [Google Scholar]

- Brundtland, G. H. (1987). Our common future: Report of the world commission on environment and development. UN-Dokument A/42/427. Available online: http://www.un-documents.net/ocf-ov.htm (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Casper, J., & Bunds, K. (Eds.). (2020). Sport and sustainability [Special issue]. Sustainability, 12(20). Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/journal/sustainability/special_issues/Sport_Sustainability (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Cho, S., Choi, H., & Kim, Y. (2019). The relationship between perceived coaching behaviors, competitive trait anxiety, and athlete burnout: A cross-sectional study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(8), 1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, D., & Cruickshank, A. (2014). The P7approach to the Olympic challenge: Sharing a practical framework for mission preparation and execution. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 13(1), 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comotto, S., Bottoni, A., Moci, E., & Piacentini, M. F. (2015). Analysis of session-RPE and pro-file of mood states during a triathlon training camp. The Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness, 55(4), 361–367. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, G. M., Fletcher, D., & Carroll, C. (2020). Psychosocial functioning of Olympic coaches and its perceived effect on athlete performance: A systematic review. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 14(1), 278–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, G. M., Fletcher, D., & Peyrebrune, M. (2021). Olympic coaching excellence: A quantitative study of Olympic swimmers’ perceptions of their coaches. Journal of Sports Sciences, 39(19), 2117–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrêa, M. F., Brandão, R., Souza, V. H., Miranda, M. L. J., Angelo, D. L., Reyes-Bossio, M., & Villas Boas, M., Jr. (2023). Psychologic training program and mental toughness development: An integrative revision of literature. Cuadernos de Psicología del Deporte, 23(1), 248–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of Europe. (n.d.). Sport and the sustainable development goals. Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/sport/sdgs (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Cury, R., Kennelly, M., & Howes, M. (2022). Environmental sustainability in sport: A systematic literature review. European Sport Management Quarterly, 23(1), 13–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daley, M. M., Shoop, J., & Christino, M. A. (2023). Mental health in the specialized athlete. Current Reviews in Musculoskeletal Medicine, 16(9), 410–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeMichelis, B. (2007, February 28). AC Milan’s “Mind Room” and sport psychology. 11th Annual Meeting of the Biofeedback Foundation of Europe, Berlin, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- Di Fabio, A. (2017). The psychology of sustainability and sustainable development for well-being in organizations. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Fabio, A., & Rosen, M. A. (2018). Opening the black box of psychological processes in the science of sustainable development: A new frontier. European Journal of Sustainable Development Research, 2(4), 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fabio, A., & Svicher, A. (2021). The psychology of sustainability and sustainable development: Advancing decent work, inclusivity, and positive strength-based primary preventive interventions for vulnerable workers. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 718354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doherty, R., Madigan, S. M., Nevill, A., Warrington, G., & Ellis, J. G. (2023). The impact of long haul travel on the sleep of elite athletes. Neurobiology of Sleep and Circadian Rhythms, 15, 100102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]