1. Introduction

The quality of the student–teacher relationship is a critical factor for academic success, particularly in mathematics. Evidence from a systematic review (

Di Lisio et al., 2025) and recent empirical work (

C. Wang et al., 2024) indicates that positive student–teacher relationships enhance students’ self-confidence and reduce mathematics-related anxiety, leading to improved academic performance. Moreover, recent empirical work reports that teacher support is associated with increased student interest and achievement in mathematics (e.g.,

Chang et al., 2023). Further, new studies highlight that supportive teacher–student interactions foster stronger engagement and persistence in mathematics learning (

Chui & Chui, 2024;

Jung et al., 2023).

However, the existing literature presents limitations regarding the study of the student–teacher relationship in Grade 12, especially among students with learning difficulties. Recent research highlights the need for further studies focusing specifically on this age group and examining how the student–teacher relationship impacts academic performance (

Joswick et al., 2023;

Di Lisio et al., 2025).

This study addresses significant gaps in the existing research by explicitly focusing on the student–teacher relationship in Grade 12 mathematics, a crucial educational stage characterized by high academic demands and stress related to university entrance examinations. Its originality lies in the direct comparative approach it adopts, investigating differences between students with and without learning difficulties—an aspect that remains relatively unexplored in the literature. The novel contribution of the present work includes providing empirical evidence about how relationship dynamics differ based on students’ learning profiles, thus offering valuable insights for educators aiming to foster supportive and effective classroom environments. Additionally, by exploring how these differences impact academic performance, the study offers practical implications for targeted pedagogical interventions designed to enhance mathematics achievement, particularly among students experiencing learning difficulties.

The aim of the present study is to examine how the quality of the student–teacher relationship in Grade 12 mathematics relates to academic performance, with a particular emphasis on students with diverse learning needs and students with typical learning development. Specifically, the study addresses the following research questions:

How do students with diverse learning needs and students with typical learning development perceive their relationship with their mathematics teacher in terms of closeness, support, and conflict?

How is the perceived quality of the student–teacher relationship associated with students’ academic performance in mathematics?

Are there statistically significant differences in both relationship perceptions and academic performance between students with diverse learning needs and students with typical learning development?

1.1. Literature Review

Perceptions of the Student–Teacher Relationship in Grade 12 Mathematics

The quality of the student–teacher relationship has been widely explored, as it plays a critical role in students’ emotional and academic development (

Di Lisio et al., 2025). In secondary education, students who experience supportive and positive relationships with their teachers tend to develop higher levels of confidence and trust in the subject matter (

C. Wang et al., 2024;

Spilt et al., 2012). A recent study found that this relational strength enhances academic engagement by increasing perceived social support and alleviating academic pressure (

Liu, 2024). Evidence from a recent systematic review (

Di Lisio et al., 2025) indicates that environments where teachers cultivate acceptance and empathy support students’ adjustment and cognitive growth, including in demanding subjects such as Grade 12 mathematics. Complementary empirical studies also highlight that teacher–student relationships shape broader developmental domains, including academic, emotional, and social outcomes (

C. Wang et al., 2024;

Zhu et al., 2022;

Chang et al., 2023). In addition, case study evidence suggests that the combined influence of teacher and parental support can affect students’ stress, well-being, interest in mathematics, and achievement (

Wijaya et al., 2022). Taken together, these findings converge to affirm the critical impact of relational dynamics on both the academic and psychosocial dimensions of secondary-level mathematics learning.

1.2. Relationship Quality and Academic Achievement

Recent empirical studies have shown a strong link between positive teacher–student relationships and academic performance, especially in cognitively demanding subjects such as mathematics (

C. Wang et al., 2024;

Chang et al., 2023). Meta-analytic and systematic review evidence indicates that students who feel supported and recognized by their teachers tend to engage more actively in the learning process and achieve higher academic outcomes (

Emslander et al., 2025;

Di Lisio et al., 2025). In fact, a supportive teacher relationship may serve as a protective factor against math-related anxiety, improving both cognitive and emotional engagement (

C. Wang et al., 2024). Recent studies confirm that teacher empathy and a sense of fairness enhance students’ feelings of safety and confidence, which in turn foster improved school performance and reduce avoidance behaviours (

Liu, 2024;

Zhou et al., 2023). Moreover, empirical and case study evidence has linked trust-based and reciprocal teacher–student interactions to lower school-related stress and higher participation in mathematics learning (

G. Wang et al., 2024;

Wijaya et al., 2022). While relational quality alone is not sufficient to guarantee academic improvement, students who maintain close, positive, and supportive relationships with their teachers tend to outperform peers who experience frequent conflict or a lack of support (

Yang et al., 2024). In secondary education, this dynamic appears to strengthen students’ academic self-efficacy, resilience, and willingness to engage with cognitively complex tasks (

Chang et al., 2023;

Di Lisio et al., 2025). Furthermore, meta-analytic evidence indicates that such relationships can be particularly beneficial for students facing additional challenges or vulnerabilities, providing both motivational and emotional support that facilitate sustained academic engagement (

Emslander et al., 2025).

1.3. Differences Between Students with Diverse Learning Needs and Students with Typical Learning Development

Recent research grounded in Vygotskian theory highlights the importance of interaction, differentiated instruction, and positive classroom climate as key contributors to academic engagement and self-confidence (

Spilt et al., 2012;

Di Lisio et al., 2025). Students with diverse learning needs often encounter specific challenges in building strong relationships with teachers and achieving academically. These challenges are linked to factors such as insufficient instructional adaptation, limited teacher training in inclusive practices, and students’ heightened feelings of rejection or failure (

Chang et al., 2023).

Studies indicate that the absence of a supportive teacher relationship may lead to increased frustration and lower self-esteem, thereby reducing student participation and increasing the risk of academic failure (

Pastore & Luder, 2021;

Vogt et al., 2021). Many students hesitate to seek help due to fear of criticism or rejection, resulting in limited interaction and restricted access to support. At the same time, some teachers may hold lower expectations or may not implement adequate strategies to foster trust and confidence in these students.

A lack of relational support often leads to emotional disengagement, heightened conflict, and diminished academic motivation (

Chang et al., 2023). However, a teacher’s empathetic and inclusive attitude can act as a strong protective factor, fostering a sense of belonging and improving school integration and academic success (

Di Lisio et al., 2025;

Longobardi et al., 2016;

Zhu et al., 2022).

Finally, numerous studies agree that implementing individualized instructional strategies and enhancing teacher communication skills are essential to overcoming barriers and improving both relational quality and academic outcomes for students with diverse learning needs (

G. Wang et al., 2024;

Spilt et al., 2012).

Beyond regional evidence, recent high-impact international scholarship has clarified the mechanisms through which teacher–student relationships influence learning across diverse contexts. For instance,

Aldrup et al. (

2022) demonstrated that teacher empathy is consistently associated with improved engagement and achievement in multiple countries.

Emslander et al. (

2025), in a second-order meta-analysis, confirmed that supportive teacher–student interactions predict student outcomes across cultural and disciplinary boundaries, highlighting the universality of these effects. Likewise,

Gebre et al. (

2025) showed that teachers’ socio-emotional competence strongly predicts student engagement, underscoring relational quality as a global mechanism of learning rather than one confined to specific systems. Additional evidence reinforces these findings:

Di Lisio et al. (

2025) synthesized relational dimensions such as the Secure Base and Safe Haven, showing their associations with academic (dis)engagement and early school leaving;

Chui and Chui (

2024) demonstrated, through structural equation modelling, that effective teaching enhances both teacher–student relationships and mathematics achievement; and

Jung et al. (

2023) highlighted how teacher academic support and relational quality predict student engagement in mathematics classrooms. Integrating these findings positions the present study within broader international debates, emphasizing the need for comparative insights into how relational dynamics operate in mathematics classrooms with diverse learners.

Taken together, the reviewed literature underscores the critical role of the student–teacher relationship in shaping students’ emotional well-being and academic outcomes in mathematics. However, there remains a lack of focused comparative studies exploring how this relationship is experienced differently by students with diverse learning needs and those with typical learning development, particularly in the demanding context of Grade 12. Building upon the theoretical and empirical foundations discussed, the present study aims to address these gaps by systematically investigating differences in perceived relationship quality and academic achievement between these two student groups, and by examining the extent to which relationship dynamics influence mathematics performance.

2. Material and Methods

This study employed a quantitative comparative design. A total of 120 Grade 12 students (aged 17–18) participated, consisting of 60 students with diverse learning needs and 60 students with typical learning development. Data collection was conducted using an adapted questionnaire that assessed students’ perceptions of their relationship with their mathematics teacher in terms of closeness, support, and conflict, as well as their academic performance in mathematics.

2.1. Theoretical Framework

The study draws upon two primary theoretical frameworks (

Table 1):

Vygotsky’s Sociocultural Theory (

Vygotsky, 1978), emphasizing mediated learning and supportive interaction between student and teacher as crucial for cognitive development.

Self-Determination Theory (

Ryan & Deci, 2000), highlighting the importance of satisfying basic psychological needs—autonomy, competence, and relatedness—for enhancing students’ academic engagement and performance, particularly among students with diverse learning needs (

C. Wang et al., 2024;

Di Lisio et al., 2025).

This study systematically integrates two theoretical frameworks. From Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory, the relational dimensions of closeness, support, and conflict are conceptualized as indicators of mediated learning within the Zone of Proximal Development, where supportive teacher scaffolding enhances progression in mathematics. From Self-Determination Theory (

Ryan & Deci, 2000), closeness and support are directly linked to the psychological needs of relatedness and competence, whereas conflict represents a barrier to autonomy and motivation. Based on this dual framework, we hypothesize that positive teacher–student relationships (closeness, support) will predict higher mathematics achievement, while negative relational dynamics (conflict) will undermine performance, with these effects being conditioned by students’ learning profiles. Thus, our hypotheses are theory-driven, bridging sociocultural interactionist perspectives with motivational frameworks of academic engagement.

2.2. Sampling and Participants

The sample consisted of 120 Grade 12 students (aged 17–18) from seven state-funded high schools (Lyceums) located in the Attica region. Of the participants, 57 (47.5%) were male and 63 (52.5%) were female, ensuring gender balance within the sample.

Purposive sampling was employed to achieve an equitable distribution across gender and to ensure sufficient representation of students with diverse learning needs and students with typical learning development (60 in each group). This non-probability sampling method was selected because it enables the deliberate inclusion of participants who meet specific characteristics relevant to the research objectives, thereby enhancing the relevance and applicability of the findings (

Etikan et al., 2016). The selection of students with diverse learning needs was based on the recommendations of their mathematics teachers, who were familiar with their learning profiles and academic histories. Students with typical learning development were selected from the same classrooms to ensure matched classroom conditions and instructional context, thereby controlling for potential differences in teaching style, curriculum coverage, and classroom climate.

Inclusion criteria for students with diverse learning needs were based on formal teacher documentation and pedagogical assessments, while exclusion criteria included students without sufficient school records or those unwilling to provide consent. All participants and their guardians provided written informed consent, and school principals approved the study in line with ethical protocols of the Greek Ministry of Education. To ensure comparability, students with typical learning development were recruited from the same classrooms as those with diverse needs, thereby controlling for instructional and contextual factors. Although the sample was purposive and regionally limited to Attica, it reflects the demographic and academic composition of state-funded Grade 12 classrooms in Greece, enhancing ecological validity while limiting broader representativeness.

Academic performance was measured using the students’ final mathematics grades for the first semester of the school year, as recorded in official school records. These grades were assigned by their mathematics teachers in accordance with the national assessment standards of the Greek Ministry of Education. The grading system in Greek high schools ranges from 0 to 20, with 10 as the minimum passing grade. This system reflects students’ overall performance, including both written and oral assessments. The use of authentic academic records ensured ecological validity and offered a reliable, contextually grounded measure of academic achievement (

Brookhart, 2013;

McMillan, 2019).

2.3. Research Design

The study followed a quantitative methodological approach using a structured questionnaire. Data were collected through an adapted version of the Teacher–Student Relationship Inventory (

Ang, 2005), which evaluates the dimensions of closeness, support, and conflict in the student–teacher relationship (see

Appendix A). Although the adapted version was not pilot tested in the Greek context, its adaptation relied on established validation studies confirming the instrument’s psychometric robustness among adolescent populations (

Ang et al., 2020;

Pham et al., 2022). In addition, students’ academic performance in mathematics was recorded based on their official first-semester grades.

2.4. Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics (means and standard deviations) were computed for each dimension of the adapted Teacher–Student Relationship Inventory (TSRI)—closeness, support, and conflict—as well as for students’ academic performance in mathematics. The internal consistency of the questionnaire was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for each dimension, with values above 0.70 indicating acceptable reliability.

Beyond reliability, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) using AMOS 29 supported the three-factor structure of the TSRI (closeness, support, conflict), with excellent model fit indices (χ

2/df = 1.94, CFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.95, RMSEA = 0.057). All factor loadings exceeded 0.70 (

p < 0.001), confirming the construct validity of the scales (

Byrne, 2016).

To address the research questions, a series of statistical analyses was performed. First, the Shapiro–Wilk test was applied to examine the normality of each variable within the two student groups: students with diverse learning needs and students with typical learning development. Since all p-values exceeded the 0.05 threshold, the assumption of normality was met, allowing for the use of parametric tests.

Independent samples t-tests were then conducted to compare the two groups across the three relationship dimensions, with effect sizes calculated using Cohen’s d to interpret the magnitude of differences. Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated separately for each group to explore the associations between closeness, support, conflict, and academic performance.

Additionally, moderation analyses were performed using Hayes’ PROCESS macro (Model 1) in SPSS. In these models, closeness, support, and conflict were specified as predictors, mathematics achievement as the outcome variable, and students’ learning profile (diverse vs. typical development) as the moderator. This approach enabled the examination of conditional effects, providing insights into whether the strength of teacher–student relationship dimensions varied depending on students’ learning profiles.

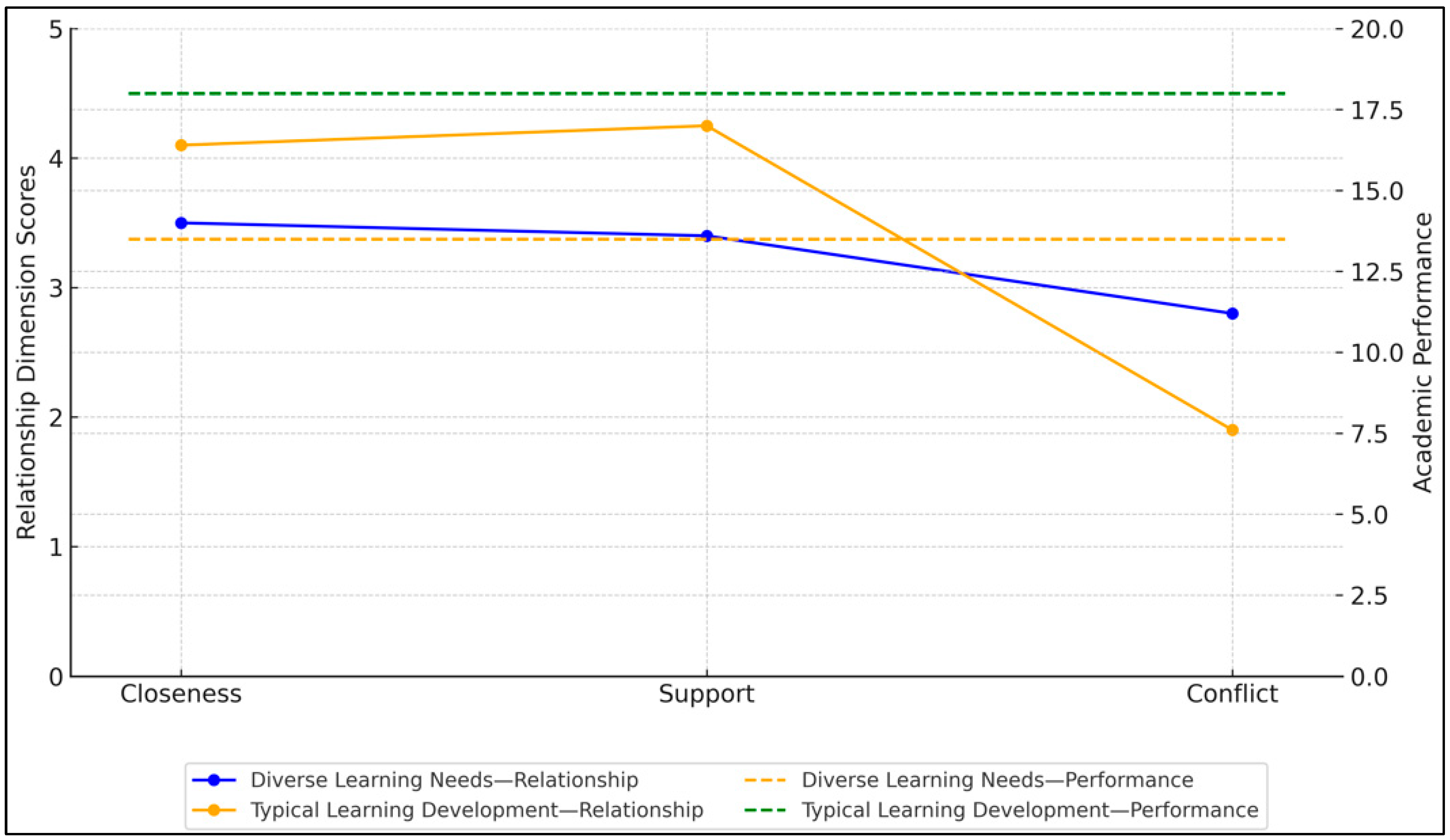

All statistical analyses were carried out using IBM SPSS Statistics, Version 29. The figure illustrating the relationship dimensions and mathematics performance (

Figure 1) was created using Microsoft Excel 2021 based on the descriptive statistics obtained from the analysis.

3. Results

This section presents the statistical analyses used to examine the relationship between student–teacher interaction and academic performance in Grade 12 mathematics, focusing on two groups: students with diverse learning needs and students with typical learning development. The results include a reliability analysis, tests of normality, independent samples t-tests, Pearson correlations, and visual representations through box plots and scatter plots.

The internal consistency of the adapted Teacher–Student Relationship Inventory (TSRI) was assessed using Cronbach’s α for each subscale. The closeness subscale showed high reliability (α = 0.87), the support subscale demonstrated excellent reliability (α = 0.91), and the conflict subscale showed good reliability (α = 0.84). These values indicate that the measurement scales were internally consistent and appropriate for further statistical analysis.

To ensure the appropriateness of parametric tests, the Shapiro–Wilk test was applied to examine the distribution of core variables across both student groups. As shown in

Table 2, all

p-values were above 0.05, confirming that the variables were normally distributed and parametric tests could be applied.

Independent samples

t-tests revealed statistically significant differences in all three relationship dimensions between the two groups. As presented in

Table 2, students with typical learning development reported higher levels of closeness and support and lower levels of conflict than their peers with diverse learning needs. Effect sizes (Cohen’s d) ranged from 0.80 to 1.08, indicating large effects.

To examine how relationship dimensions relate to academic performance, Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated separately for each group.

Table 3 presents the results for students with diverse learning needs, showing that both

closeness (r = 0.34,

p < 0.05) and

support (r = 0.41,

p < 0.001) were positively associated with academic performance, whereas

conflict (r = −0.29,

p < 0.05) was negatively related.

When examining students with typical learning development (

Table 4), a similar but slightly stronger pattern emerges compared to students with diverse learning needs (

Table 5): closeness (r = 0.39,

p < 0.001) and support (r = 0.45,

p < 0.001) had stronger positive links with performance, while conflict (r = −0.36,

p < 0.001) showed a more pronounced negative association. Together, these findings suggest that supportive, low-conflict student–teacher relationships are consistently linked to higher mathematics achievement, with the effect being somewhat stronger among students with typical learning development.

The consistent positive associations for closeness and support, coupled with the negative link for conflict, underline the importance of supportive and low-conflict teacher–student relationships in promoting mathematics achievement. This effect appears somewhat stronger among students with typical learning development.

These patterns are visually summarised in

Figure 1, which depicts the three relationship dimensions—closeness, support, and conflict—and academic performance side by side for both groups. Students with typical learning development reported higher

closeness (M = 4.10) and

support (M = 4.18), alongside lower

conflict (M = 1.96), achieving an average score of 17.8/20 in mathematics. In contrast, students with diverse learning needs reported lower

closeness (M = 3.52) and

support (M = 3.45), alongside higher

conflict (M = 2.78), with a lower average mathematics score of 13.5/20.

To further explore conditional effects, moderation analyses were performed using Hayes’ PROCESS macro (Model 1). Results showed that the effect of support on mathematics achievement was significantly moderated by learning profile (interaction term b = 0.42, SE = 0.15, p < 0.01). Specifically, support had a stronger positive effect for students with typical learning development compared to those with diverse learning needs. In contrast, the moderating effect for closeness and conflict was nonsignificant. These findings suggest that while relational quality is beneficial across groups, its academic payoff may be contingent on the presence or absence of learning difficulties, highlighting the importance of tailoring relational strategies to diverse learner needs.

Overall, the visual and statistical results converge on the conclusion that higher levels of closeness and support, paired with lower conflict, are associated with better mathematics performance, particularly for students with typical learning development.

4. Discussion

This study examined how the perceived quality of the student–teacher relationship in Grade 12 mathematics relates to academic performance, comparing students with diverse learning needs to those with typical learning development. The results strongly reaffirm the central role of supportive, low-conflict teacher–student relationships in enhancing both cognitive and emotional engagement, which is consistent with meta-analytic and systematic review evidence highlighting that an environment of acceptance, empathy, and responsiveness fosters student adjustment and cognitive growth (

Chang et al., 2023;

Cai et al., 2023;

Emslander et al., 2025;

Di Lisio et al., 2025;

Gebre et al., 2025;

Hofkens & Pianta, 2022;

C. Wang et al., 2024;

Savina, 2025).

Students with typical learning development reported significantly higher levels of closeness and support, and lower levels of conflict, compared to their peers with diverse learning needs. Large effect sizes confirmed that these differences were both statistically and practically significant. This finding mirrors prior research showing that students with diverse learning needs often encounter barriers to developing strong teacher relationships due to insufficient instructional adaptation, lower teacher expectations, and limited inclusive training (

Ahmad & Parween, 2021;

Joswick et al., 2023;

Pastore & Luder, 2021;

Vogt et al., 2021;

Kourkoutas & Giovazolias, 2015;

Kimhi & Bar Nir, 2025). Such relational challenges have been linked to reduced participation, lower self-efficacy, and diminished academic outcomes in mathematics and other cognitively demanding subjects (

Pozas et al., 2021;

Spilt et al., 2012;

Hofkens & Pianta, 2022).

The correlation analysis revealed that closeness and support were positively associated with mathematics performance, while conflict was negatively related, across both student groups. These patterns align with evidence that positive teacher–student relationships can buffer against mathematics-related anxiety, foster perseverance, and enhance achievement (

Chang et al., 2023;

Cai et al., 2023;

Lin et al., 2020;

C. Wang et al., 2024;

Savina, 2025). The slightly stronger associations among students with typical learning development suggest that relational quality may have a more stable impact when systemic and instructional barriers are minimal. However, even moderate relational improvements for students with diverse learning needs could yield significant gains, as prior work has shown that targeted support can enhance engagement and achievement even for students with additional challenges (

Di Lisio et al., 2025;

Pastore & Luder, 2021;

Pozas et al., 2021;

Vogt et al., 2021;

Cai et al., 2023).

From a theoretical standpoint, these findings are well aligned with Vygotsky’s view of learning as a socially mediated process, where interaction with more-knowledgeable others supports progression within the learner’s Zone of Proximal Development (

Vygotsky, 1978). They also resonate with self-determination theory, which emphasises relatedness and autonomy support as key drivers of intrinsic motivation and sustained effort (

Ryan & Deci, 2000). The elevated conflict scores among students with diverse learning needs reflect earlier findings that relational strain undermines trust, reduces help-seeking behaviours, and lowers willingness to engage in challenging tasks (

Chang et al., 2023;

Pozas et al., 2021;

Hofkens & Pianta, 2022).

These results have important implications for practice and policy. Professional development should equip teachers with strategies to build trust, provide differentiated support, and manage conflict constructively, particularly for students with diverse learning needs (

Kourkoutas & Giovazolias, 2015;

Kimhi & Bar Nir, 2025;

Pastore & Luder, 2021;

Vogt et al., 2021). Relational pedagogy should be embedded in teacher training and evaluation frameworks, recognising that the quality of interactions is a central dimension of teaching effectiveness (

Emslander et al., 2025;

Di Lisio et al., 2025;

Savina, 2025;

Hofkens & Pianta, 2022). Policy frameworks for inclusive education should explicitly address strategies to foster supportive relationships, as these contribute not only to improved academic performance but also to emotional well-being, resilience, and long-term engagement. In mathematics classrooms, where cognitive demands are high, cultivating a climate of empathy, fairness, and responsiveness is essential for closing performance gaps and ensuring equitable opportunities for success (

Chang et al., 2023;

Cai et al., 2023;

C. Wang et al., 2024;

Pozas et al., 2021).

Beyond confirming established associations, this study extends theoretical understanding in two ways. First, it bridges sociocultural theory and self-determination theory by demonstrating that relational dynamics in mathematics classrooms both scaffold cognitive progression (

Vygotsky, 1978) and satisfy psychological needs (

Ryan & Deci, 2000), thereby enhancing motivation and achievement. Second, our moderation analyses provide novel evidence that the academic impact of teacher support is conditional on students’ learning profiles, suggesting that inclusive classrooms require differentiated relational strategies. In doing so, the study challenges the assumption of uniform relational benefits, instead positioning relational quality as a mechanism that operates differently depending on student characteristics. This contribution enriches global debates on equity, inclusion, and the relational foundations of academic success.

Limitations and Future Research

While this study provides robust evidence on the relationship between student–teacher interaction and academic performance in Grade 12 mathematics, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the data were collected from a single academic year and within a specific educational context, which may limit the generalisability of the findings to other regions, school systems, or subject areas (

Creswell & Creswell, 2018;

Cohen et al., 2018). Longitudinal designs would be valuable to assess how relationship dynamics evolve over time and their long-term impact on academic trajectories. Additionally, the non-probability sampling method and the focus on a single region limit external validity. Findings should therefore be interpreted with caution when generalizing to broader populations or international contexts. Future research employing stratified random sampling and cross-national comparative designs would provide stronger evidence of the universality and contextual variability of relational mechanisms. Future research should sample comparable schools across additional Greek regions and, where feasible, undertake international comparisons to strengthen external validity.

Second, the reliance on self-reported perceptions introduces the possibility of response bias, as students’ evaluations may be influenced by social desirability or temporary emotional states (

Saleh & Bista, 2017). Triangulating perceptions with classroom observations, teacher reports, and behavioural data could strengthen validity and provide a more nuanced understanding of relationship quality.

Third, although the adapted Teacher–Student Relationship Inventory (TSRI) demonstrated high internal consistency, it focused on three broad relational dimensions—closeness, support, and conflict—which may not fully capture the complexity of interpersonal dynamics in mathematics instruction (

Emslander et al., 2025;

Di Lisio et al., 2025). Future research could incorporate additional constructs such as teacher fairness, instructional clarity, and feedback quality, which have been shown to influence student engagement and achievement (

Chang et al., 2023;

C. Wang et al., 2024). Moreover, the instrument was not pilot tested in the Greek context, although prior validation studies support its psychometric robustness among adolescent populations (e.g.,

Ang et al., 2020;

Pham et al., 2022).

Fourth, while the study differentiated between students with diverse learning needs and those with typical learning development, the category of “diverse learning needs” included a heterogeneous group. Prior research has shown that specific subgroups—such as students with dyslexia, ADHD, or emotional and behavioural difficulties—may experience unique relational challenges and academic barriers (

Joswick et al., 2023;

Pastore & Luder, 2021;

Vogt et al., 2021). Disaggregating these groups in future studies would allow for more targeted interventions.

Finally, the study’s cross-sectional design limits causal inference. While strong associations were found between relationship quality and mathematics performance, it remains possible that higher-achieving students perceive their relationships more positively due to academic success, rather than the relationship itself driving performance. Experimental and quasi-experimental designs, including intervention studies focused on teacher–student relationship enhancement, could provide stronger evidence of causality (

Vygotsky, 1978;

Ryan & Deci, 2000).

Future research should also explore how cultural factors, teacher professional development, and school-wide relational climates influence the quality of interactions in mathematics classrooms. Given the growing emphasis on inclusive education, comparative studies across different educational systems could help identify best practices that effectively support both students with diverse learning needs and those with typical learning development.

5. Conclusions

This study offers novel insights into how the quality of student–teacher relationships in Grade 12 mathematics differs between students with diverse learning needs and those with typical learning development, and how these relationships are linked to academic achievement. While previous research has documented the general importance of relational dynamics in education (

Emslander et al., 2025;

Di Lisio et al., 2025;

Spilt et al., 2012), the present study extends this knowledge by providing a direct comparative analysis between these two student groups within the high-stakes context of advanced mathematics.

The findings highlight a consistent pattern: higher levels of closeness and support, coupled with lower levels of conflict, are strongly associated with better mathematics performance. Importantly, this relationship was evident for both groups yet appeared somewhat stronger among students with typical learning development. This comparative dimension is a key contribution, as few prior studies have simultaneously examined relational perceptions and performance outcomes across these populations in the final year of secondary education.

Furthermore, the integration of robust psychometric validation, parametric statistical testing, and visual data representation strengthens the methodological rigour and offers a replicable approach for future investigations. By focusing on Grade 12 mathematics, a subject often associated with elevated academic pressure and performance anxiety (

C. Wang et al., 2024;

Chang et al., 2023), this study addresses a critical but underexplored intersection of cognitive and relational factors.

In practical terms, the results underscore the need for teacher training programs that prioritise relational competence, especially in inclusive classrooms. For policymakers and school leaders, the study provides empirical support for designing interventions that not only target academic content delivery but also systematically foster trust, support, and constructive communication between teachers and students.

By bridging a clear gap in the literature and offering actionable implications, this research advances both theoretical understanding and practical strategies for enhancing student outcomes in mathematics. In doing so, it reaffirms that the relational dimension of teaching is not an auxiliary element but a core driver of academic success—particularly in contexts where the stakes, challenges, and opportunities for growth are at their highest.