Examining Resilience, Self-Efficacy and Environmental Chaos Relationship in Early Childhood Education and Care Teachers

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

1.1.1. Teacher Resilience

1.1.2. Self-Efficacy in ECEC

1.1.3. Environmental CHAOS in Educational Contexts

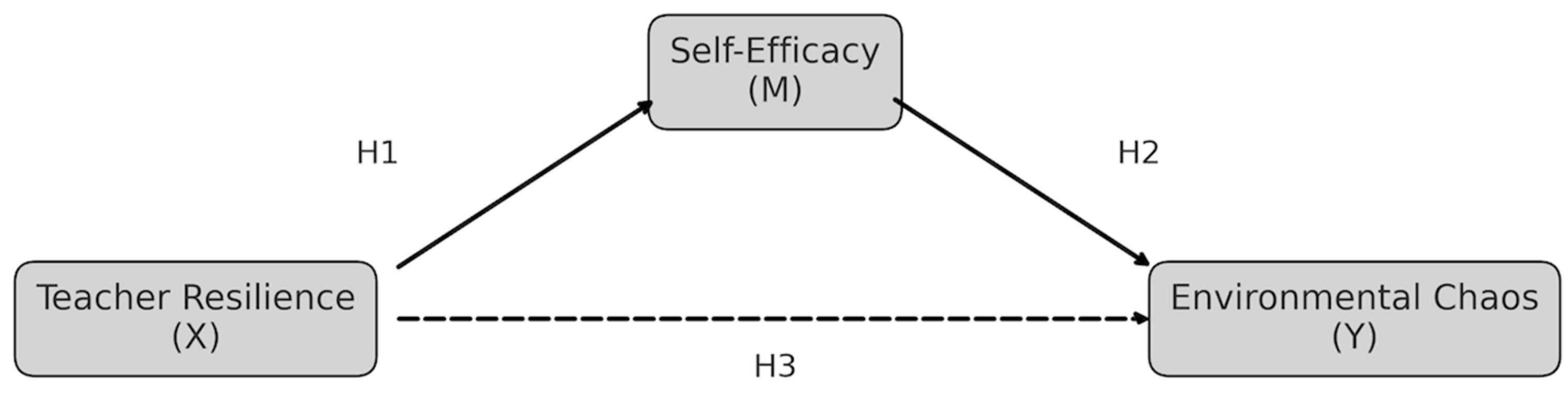

1.1.4. The Mediating Role of Self-Efficacy

1.2. The Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Teacher Resilience

2.2.2. Teacher Self-Efficacy

2.2.3. Environmental CHAOS

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations and Future Directions

4.2. Implications

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ECEC | Early Childhood Education and Care |

| EFA | Exploratory Factor Analysis |

| SEM | Structural Equation Model |

References

- American Psychological Association. (2025). The road to resilience. American Psychological Association. Available online: https://www.apa.org/topics/resilience (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Bagdžiūnienė, D., Kazlauskienė, A., Nasvytienė, D., & Sakadolskis, E. (2023). Resources of emotional resilience and its mediating role in teachers’ well-being and intention to leave. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1305979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2007). The job demands-resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 22(3), 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. (2023). Cultivate self-efficacy for personal and organizational effectiveness. In Principles of organizational behavior: The handbook of evidence-based management (3rd ed., pp. 113–135). Wiley. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltman, S., Mansfield, C., & Price, A. (2011). Thriving not just surviving: A review of research on teacher resilience. Educational Research Review, 6(3), 185–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blewitt, C., Morris, H., Nolan, A., Jackson, K., Barrett, H., & Skouteris, H. (2020). Strengthening the quality of educator-child interactions in early childhood education and care settings: A conceptual model to improve mental health outcomes for preschoolers. Early Child Development and Care, 190, 991–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buettner, C. K., Jeon, L., Hur, E., & Garcia, R. E. (2016). Teachers’ social–emotional capacity: Factors associated with teachers’ responsiveness and professional commitment. Early Education and Development, 27(7), 1018–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, S., & Jeon, L. (2025). Associations among preschool classroom chaos, work climates, and child outcomes. Teaching and Teacher Education, 153, 104821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadima, J., Ferreira, T., Guedes, C., Alves, D., Grande, C., Leal, T., Piedade, F., Lemos, A., Agathokleous, A., Charalambous, V., Vrasidas, C., Michael, D., Ciucurel, M., Chirlesan, G., Marinescu, B., Duminica, D., Vatou, A., Tsitiridou-Evangelou, M., Zachopoulou, E., & Grammatikopoulos, V. (2025). Does support for professional development in early childhood and care settings matter? A study in four countries. Early Childhood Education Journal, 53, 1181–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell-Sills, L., & Stein, M. B. (2007). Psychometric analysis and refinement of the connor–davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC): Validation of a 10-item measure of resilience. Journal of Traumatic Stress: Official Publication of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies, 20(6), 1019–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, S., & Sutton, A. (2024). Early childhood teachers’ emotional labour: The role of job and personal resources in protecting well-being. Teaching and Teacher Education, 148, 104699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, S., Maneewan, S., & Koul, R. (2023). An examination of the relationship between the perceived instructional behaviours of teacher educators and pre-service teachers’ learning motivation and teaching self-efficacy. Educational Review, 75(2), 264–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coley, R. L., Lynch, A. D., & Kull, M. (2015). Early exposure to environmental chaos and children’s physical and mental health. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 32, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corapci, F. (2010). Child-care chaos and child development. In G. W. Evans, & T. D. Wachs (Eds.), Chaos and its influence on children’s development: An ecological perspective (pp. 67–82). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corapci, F., Eroglu-Ada, F., Kalkan, R. B., & Duman, E. A. (2023). Classroom chaos and program quality in early child care and education programs: A study from Turkey. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 65, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniilidou, A., & Platsidou, M. (2018). Teachers’ resilience scale: An integrated instrument for assessing protective factors of teachers’ resilience. Hellenic Journal of Psychology, 15(1), 15–39. [Google Scholar]

- Doan, S. N., & Evans, G. W. (2020). Chaos and instability from birth to age three. The Future of Children, 30(2), 93–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. (2025). Classroom teachers and academic staff by education level, programme orientation, sex and age groups. Eurostat. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Early_childhood_education_statistics#Resources_.E2.80.93_staff (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Gee, D. G., & Cohodes, E. M. (2021). Influences of caregiving on development: A sensitive period for biological embedding of predictability and safety cues. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 30(5), 376–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, A. A., Jeon, L., & Buettner, C. K. (2019). Chaos and commitment in the early childhood education classroom: Direct and indirect associations through teaching efficacy. Teaching and Teacher Education, 81, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haisraeli, A., & Fogiel-Bijaoui, S. (2023). Parental involvement in school pedagogy: A threat or a promise? Educational Review, 75(4), 597–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, S., Weiss, M., Newman, A., & Hoegl, M. (2020). Resilience in the workplace: A multilevel review and synthesis. Applied Psychology, 69(3), 913–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B. Y., Li, Y., Wang, C., Reynolds, B. L., & Wang, S. (2019). The relation between school climate and preschool teacher stress: The mediating role of teachers’ self-efficacy. Journal of Educational Administration, 57(6), 748–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B. Y., Li, Y., Wang, C., Wu, H., & Vitiello, G. (2021). Preschool teachers’ self-efficacy, classroom process quality, and children’s social skills: A multilevel mediation analysis. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 55, 242–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J., Wang, Y., & You, X. (2016). The job demands-resources model and job burnout: The mediating role of personal resources. Current Psychology, 35(4), 562–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S., Yin, H., & Lv, L. (2019). Job characteristics and teacher well-being: The mediation of teacher self-monitoring and teacher self-efficacy. Educational Psychology, 39(3), 313–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, P. A. (2015). Early childhood teachers’ well-being, mindfulness, and self-compassion in relation to classroom quality and attitudes towards challenging students. Mindfulness, 6, 732–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, P. A., & Greenberg, M. T. (2009). The prosocial classroom: Teacher social and emotional competence in relation to student and classroom outcomes. Review of Educational Research, 79(1), 491–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, L., Hur, E., & Buettner, C. K. (2016). Child-care chaos and teachers’ responsiveness: The indirect associations through teachers’ emotion regulation and coping. Journal of School Psychology, 59, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, W. B., & Griffin, K. A. (2024). On being a mentor: A guide for higher education faculty. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. B. (2023). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Koulierakis, G., Daglas, G., Grudzien, A., & Kosifidis, I. (2019). Burnout and quality of life among Greek municipal preschool and kindergarten teaching staff. Education 3–13, 47(4), 426–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krousorati, K., Vatou, A., Gregoriadis, A., & Grammatikopoulos, V. (2022). Supporting teachers to promote psychological resilience and well-being in the Greek early childhood education. In Training perspectives and experiences in early childhood education (pp. 9–21). Paula Frassineti Escola Superior de Educacao. [Google Scholar]

- Leithwood, K., & Sun, J. (2012). The nature and effects of transformational school leadership: A meta-analytic review of unpublished research. Educational Administration Quarterly, 48(3), 387–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemos, A., Piedade, F., Ferreira, T., Guedes, C., Alves, D., Grande, C., Leal, T., Cadima, J., Vatou, A., Evangelou, M., Manolitsis, G., Mouzaki, A., Kypriotaki, M., Oikonomidis, V., Grammatikopoulos, V., Michael, D., Charalambous, V., Vrasidas, C., Agathokleous, A., … Delia, D. (2025). Psychometric Properties of Maslach Burnout Inventory–Educators Survey (MBI-ES). European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S. (2023). The effect of teacher self-efficacy, teacher resilience, and emotion regulation on teacher burnout: A mediation model. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1185079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansfield, C. F., Beltman, S., Broadley, T., & Weatherby-Fell, N. (2016). Building resilience in teacher education: An evidenced informed framework. Teaching and Teacher Education, 54, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masten, A. S. (2014). Global perspectives on resilience in children and youth. Child Development, 85(1), 6–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matheny, A. P., Jr., Wachs, T. D., Ludwig, J. L., & Phillips, K. (1995). Bringing order out of chaos: Psychometric characteristics of the confusion, hubbub, and order scale. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 16(3), 429–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCallum, F. (2021). Teachers’ wellbeing during times of change and disruption. In Wellbeing and resilience education (pp. 183–208). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, D., Vatou, A., Charalambous, V., Pezirkianidis, C., Vrasidas, C., Evangelou-Tsitiridou, M., Manolitsis, G., Mouzaki, A., Kypriotaki, M., Oikonomidis, V., Piedade, F., Lemos, A., Alves, D., Grande, C., Cadima, J., Chirlesan, G., Ciucurel, M.-M., Delia, D., & Grammatikopoulos, V. (2025). Exploring the factor structure and measurement invariance of the teacher subjective wellbeing questionnaire across four European countries. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 43, 417–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D., & Ramirez, G. (2022). Frustration in the classroom: Causes and strategies to help teachers cope productively. Educational Psychology Review, 34(4), 1955–1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, J., & Pearce, J. (2012). Relationships and early career teacher resilience: A role for school principals. Teachers and Teaching, 18(2), 249–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purper, C. J., Thai, Y., Frederick, T. V., & Farris, S. (2023). Exploring the challenge of teachers’ emotional labor in early childhood settings. Early Childhood Education Journal, 51(4), 781–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renshaw, T. L., Long, A. C., & Cook, C. R. (2015). Assessing teachers’ positive psychological functioning at work: Development and validation of the Teacher Subjective Wellbeing Questionnaire. School Psychology Quarterly, 30(2), 289–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selman, S. B., & Dilworth-Bart, J. E. (2024). Routines and child development: A systematic review. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 16(2), 272–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J., Zhang, R., & Forsyth, P. B. (2023). The effects of teacher trust on student learning and the malleability of teacher trust to school leadership: A 35-year meta-analysis. Educational Administration Quarterly, 59(4), 744–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschannen-Moran, M., & Hoy, A. W. (2001). Teacher efficacy: Capturing an elusive construct. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(4), 751–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsigkaropoulou, E., Douzenis, A., Tsitas, N., Ferentinos, P., Liappas, I., & Michopoulos, I. (2018). Greek version of the connor-davidson resilience scale: Psychometric properties in a sample of 546 subjects. In Vivo, 32(6), 1629–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallés, A., & Clarà, M. (2023). Conceptualizing teacher resilience: A comprehensive framework to articulate the research field. Teachers and Teaching, 29(1), 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatou, A., & Gkorezis, P. (2018). Linking calling and work passion in the educational context: Work meaningfulness as a mediator. Journal of Psychological & Educational Research, 26(1), 23–39. [Google Scholar]

- Vatou, A., Gregoriadis, A., Tsigilis, N., & Grammatikopoulos, V. (2022). Teachers’ social self-efficacy: Development and validation of a new scale. Cogent Education, 9(1), 2093492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatou, A., Gregoriadis, A., Tsigilis, N., & Grammatikopoulos, V. (2023). Quality of teacher–child relationships: An exploration of its effect on children’s emergent literacy skills. International Journal of Early Childhood, 55(2), 279–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatou, A., Krousorati, K., Oikonomides, V., Manolitsis, G., Kypriotaki, M., Evangelou-Tsitiridou, M., & Grammatikopoulos, V. (2021). Current Needs of preschool teachers for professional development in greece: A focus group study. Saber e Educar, 30(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vella, S. L. C., & Pai, N. B. (2019). A theoretical review of psychological resilience: Defining resilience and resilience research over the decades. Archives of Medicine and Health Sciences, 7(2), 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachs, T. D., & Evans, G. W. (Eds.). (2010). Chaos in context. In Chaos and its influence on children’s development: An ecological perspective (pp. 3–13). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachs, T. D., Gurkas, P., & Kontos, S. (2004). Predictors of preschool children’s compliance behavior in early childhood classroom settings. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 25(4), 439–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H., Burić, I., Chang, M. L., & Gross, J. J. (2023). Teachers’ emotion regulation and related environmental, personal, instructional, and well-being factors: A meta-analysis. Social Psychology of Education, 26(6), 1651–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissenfels, M., Benick, M., & Perels, F. (2021). Can teacher self-efficacy act as a buffer against burnout in inclusive classrooms? International Journal of Educational Research, 109, 101794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zee, M., de Jong, P. F., & Koomen, H. M. (2024). The relational side of teachers’ self-efficacy: Assimilation and contrast effects of classroom relational climate on teachers’ self-efficacy. Journal of School Psychology, 103, 101297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y., Chen, S., Deng, X., Wang, S., & Shi, L. (2023). Self-efficacy and career resilience: The mediating role of professional identity and work passion in kindergarten teachers. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 33(2), 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Background Variables | N = 206 | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | %female | 97.6% |

| %male | 2.4% | |

| Age | Mean age (in years) (SD) | 38.0 (10.31) |

| Range age | 21 to 60 | |

| Teaching Experience | Mean experience (in years) (SD) | 10.4 (8.61) |

| Range experience | 1 to 35 | |

| Education Level | % Technological Educational Institute Degree | 39.3% |

| % Bachelor Degree | 49.5% | |

| % Master’s Degree | 10.7% | |

| % Doctoral Degree | 0.5% |

| CHAOS-D Items | Factor Loadings | |

|---|---|---|

| Factor 1 Chaotic Structure | Factor 2 Chaotic Atmosphere | |

| chaos_5 | 0.814 | |

| chaos_8 | 0.750 | |

| chaos_4 | 0.714 | |

| chaos_7 | 0.690 | |

| chaos_10 | 0.637 | |

| chaos_2 | 0.568 | |

| chaos_14 | 0.516 | |

| chaos_16 | 0.490 | |

| chaos_13R | 0.827 | |

| chaos_11R | 0.694 | |

| chaos_3R | 0.381 | |

| chaos_1R | 0.349 | |

| chaos_9R | 0.334 | |

| Eigenvalues | 3.59 | 1.21 |

| M (SD) | Min. | Max. | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Teacher resilience | 3.00 (0.62) | 1.20 | 4 | - | ||

| 2. Self-efficacy | 3.09 (0.48) | 1 | 4 | 0.249 ** | - | |

| 3. Chaotic structure | 2.10 (0.73) | 1 | 5 | −0.100 | −0.160 * | - |

| 4. Chaotic atmosphere | 2.31 (0.60) | 1 | 4.20 | −0.349 ** | −0.270 ** | 0.253 * |

| 95% CI | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect | Path | B | β | SE | Lower | Upper | z | p | R2 | |

| Indirect α × b | Teacher Resilience -> Self-efficacy -> Chaotic atmosphere | −0.04 | −0.05 | 0.02 | −0.09 | −0.01 | −2.01 | <0.050 | ||

| Direct c | Teacher Resilience -> Chaotic atmosphere | −0.29 | −0.30 | 0.07 | −0.42 | −0.15 | −4.11 | <0.001 | ||

| Total c’ + (α × b) | Teacher Resilience -> Chaotic atmosphere | −0.33 | −0.34 | 0.06 | −0.46 | −0.21 | −5.31 | <0.001 | 0.167 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vatou, A. Examining Resilience, Self-Efficacy and Environmental Chaos Relationship in Early Childhood Education and Care Teachers. Psychol. Int. 2025, 7, 73. https://doi.org/10.3390/psycholint7030073

Vatou A. Examining Resilience, Self-Efficacy and Environmental Chaos Relationship in Early Childhood Education and Care Teachers. Psychology International. 2025; 7(3):73. https://doi.org/10.3390/psycholint7030073

Chicago/Turabian StyleVatou, Anastasia. 2025. "Examining Resilience, Self-Efficacy and Environmental Chaos Relationship in Early Childhood Education and Care Teachers" Psychology International 7, no. 3: 73. https://doi.org/10.3390/psycholint7030073

APA StyleVatou, A. (2025). Examining Resilience, Self-Efficacy and Environmental Chaos Relationship in Early Childhood Education and Care Teachers. Psychology International, 7(3), 73. https://doi.org/10.3390/psycholint7030073