2. Materials and Methods

This study was carried out in three distinct phases, with the aim of deepening knowledge about the process of adaptation of the main informal caregivers to life after the death of the person they cared for, as well as understanding the nursing care that promotes effective adaptive responses that contribute to the transition experience of the main informal caregivers after the end of their caring role due to the death of the person they cared for. The first two phases aimed to deepen understanding of the phenomenon and to support the development of a more accurate qualitative research plan.

In the first phase, a scoping review was carried out to map the available scientific evidence on the phenomenon under study and identify gaps in knowledge. The scoping review was conducted following the Joanna Briggs Institute guidelines, using the Population, Concept, and Context strategy. The search was carried out in the EBSCO, Scopus, and Web of Science databases, covering publications until 2024 in English, Portuguese, Spanish, and French. Out of 1681 articles identified, 9 were included. Findings show that the end of the caregiving role is influenced by various factors, involves both positive and negative experiences, and highlights specific needs among post-caregivers. These results were the basis for the design of the subsequent phases of the research (

Tricco et al., 2018).

The second phase, of a quantitative nature, aimed to determine the individual lifestyles of the main informal caregivers after the end of their caring role. To this end, we decided to assess the health-promoting lifestyles profile (HPLPII) by Hendricks, C., & Pender, N (

Pender et al., 2006), translated and validated into Portuguese and for the Portuguese population by

P. Sousa et al. (

2015), for the main informal caregivers whose caring role was extinguished following the death of the person being cared for (

P. Sousa et al., 2015). It demonstrates strong internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha > 0.80) and cultural adequacy for the Portuguese population. While internal consistency for the current sample was not recalculated, the scale’s reliability has been consistently supported in national and international studies. Its multidimensional structure allows for a comprehensive assessment of lifestyle behaviors relevant to former informal caregivers. The HPLPII is a medium-range model and is highly generalizable to adult populations. The research used to create the model was based on male and female samples, young people, adults and the elderly, sick and healthy people, so it has strong empirical support (

Alligood & Tomey, 2004).

The HPLPII measures the overall health-promoting lifestyle through 52 items that simultaneously measure the lifestyle in six domains, or sub-scales, considered to be the main dimensions of a health-promoting lifestyle, which are as follows: Health Responsibility; Physical Activity; Nutrition; Interpersonal Relationships and Spiritual Growth; and Stress Management (

Alligood & Tomey, 2004;

Pender et al., 2006).

The metric proposed for each answer varies between Never (1), Sometimes (2), Often (3), and Always (4), and the overall score and score for each subscale is obtained from the average of the answers given in the set of answers or in each subgroup (

P. Sousa et al., 2015). The sampling used in this phase was non-probabilistic, of the snowball type, targeting participants who met the inclusion criteria. Dissemination and recruitment were carried out mainly through social networks such as Facebook, allowing informal caregivers to be reached across the Autonomous Regions of the Azores and Madeira and the Portuguese mainland. This strategy resulted in the participation of 66 individuals. To examine the relationships derived from the application of the HPLP II scale within the framework of Nola Pender’s Health Promotion Model (1996) (

Pender et al., 2006), a structural equation model was estimated using partial least squares (PLS-SEM). This technique, widely applied in health research, is particularly suited for analyzing complex variable relationships, exploring theoretical models, predicting outcomes, and handling small sample sizes or data that deviate from normality. A post hoc power analysis was performed using SmartPLS (Version 4.1.1.4), which indicated that a minimum of 60 cases was required to ensure adequate statistical power. As the study included 66 participants, the sample meets this threshold. The use of PLS-SEM is therefore justified both by methodological appropriateness and the exploratory nature of the study. Non-parametric statistical tests (Mann–Whitney U and Kruskal–Wallis) were applied to examine associations, considering the data’s distribution.

In the third phase, a qualitative approach was adopted, based on the Grounded Theory methodology, as proposed by (

Strauss & Corbin, 1998). This approach was considered appropriate for the exploratory nature of the study, allowing us to generate a theory based on the data about the process of adaptation of the main informal caregivers following the death of the person they cared for.

Data was collected and analyzed simultaneously. Semi-structured interviews were carried out and the open, axial and selective coding stages were applied, accompanied by the preparation of analytical memos that contributed to theoretical development.

In the open coding phase, the data was fragmented into meaningful units and assigned codes that represented emerging concepts, allowing initial categories to be identified. Subsequently, in axial coding, these categories were reorganized and related to each other by identifying causal patterns, contexts, intervening conditions, action/interaction strategies, and consequences, according to the paradigmatic model proposed by the authors. Finally, in selective coding, a central category was identified that integrated the remaining categories, allowing for the construction of a coherent explanatory theory on the experiences lived by informal caregivers after the death of the person they cared for (

Strauss & Corbin, 1998).

This process was complemented by the drawing up of analytical memos throughout the analysis, which enabled continuous and in-depth reflection on the data, as well as on the theoretical evolution under construction.

This qualitative study, with main informal caregivers, aimed to explore their perceptions and experiences related to caring, loss, and adaptation following the death of the person they cared for and the consequent extinction of their role. A semi-structured interview was chosen as the data collection tool, allowing for greater depth in the participants’ experiences. Two main questions were outlined, which allowed the participants to talk openly about the subjects: How do you characterize the phase in which you cared for your dependent family member at home? and How do you characterize the process of adapting to life after your caring role ended? Whenever necessary, questions were asked to explore aspects that had been touched on superficially.

Given that Grounded Theory was employed, theoretical sampling was applied iteratively; following the initial interviews, emerging categories guided the selection of subsequent participants, with the aim of deepening and diversifying the understanding of those categories. For instance, when the relevance of the family context emerged early in the analysis, we deliberately included participants with varied familial experiences. In this way, data collection was directly informed by ongoing theoretical development.

Theoretical saturation was considered to have been reached after the ninth interview, as no new significant properties emerged for the main categories. Interviews 10 and 11 confirmed this analytical stability. This conclusion was based on a process of concurrent data collection and analysis, regular team discussions, and the systematic use of theoretical memos, in line with the procedures described by

Strauss and Corbin (

1998) and

Charmaz (

2017).

For data reduction and analysis, we followed the three coding phases characteristic of Grounded Theory (GT) methodology: open coding, during which transcripts were segmented into meaningful units and labeled using in vivo codes where appropriate; axial coding, which involved grouping codes into categories and examining relationships among conditions, actions/interactions, and consequences; and selective coding, through which a core category was identified that integrated the other categories, forming the foundation of the emerging theory (

Strauss & Corbin, 1998;

Charmaz, 2017). Throughout this process, theoretical memos were used to refine conceptual understanding and track the development of the model (

Charmaz, 2017).

This study adopted a constructivist GT methodology, aiming to generate a mid-range theory grounded in systematically collected and analyzed empirical data. Guided by symbolic interactionism, GT emphasizes the understanding of human action and social processes through the meanings attributed by individuals to their experiences. Participants were selected through theoretical sampling, based on their relevance and experiential knowledge of the phenomenon under investigation. Data collection continued until theoretical saturation was achieved—that is, when no new significant insights emerged (

Strauss & Corbin, 1998;

Charmaz, 2017).

In total, 11 in-depth interviews were conducted, each lasting an average of 45 min. The participants presented a diverse range of sociodemographic characteristics, which enriched the dataset and enabled the development of a comprehensive and explanatory theoretical model. The interviews were transcribed and analyzed using ATLAS.ti (Version 25.0.1;

ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH, 2024) a robust tool for organizing and interpreting large volumes of qualitative data. The use of this platform facilitated a structured and transparent coding process. A total of 52 codes emerged from the analysis, reflecting the complexity and diversity of the participants’ experiences. These were subsequently clustered into seven thematic categories, based on similarities in content, frequency of occurrence, and perceived relevance within the narratives: (1) After death, (2) Difficulties felt, (3) Relational space of the death experience, (4) Management of the terminal phase, (5) Need for support, (6) What remains of the care process, and (7) Feelings that emerge in the end-of-life experience. These categories capture the multifaceted impact of bereavement and the reconfiguration of caregivers’ identities following the end of their caring role, highlighting the critical need for sensitive and multi-sectoral nursing interventions.

The analytical process followed GT principles—open, axial, and selective coding—alongside constant comparative methods. Analytical memos were used to reflect on emerging patterns and theoretical connections. This iterative and flexible approach ensured a continuous interplay between data collection and analysis, supporting the construction of a central category and an integrated theoretical model. Rigor was maintained through close attention to participants’ perspectives and the systematic integration of data, theory, and interpretation (

Strauss & Corbin, 1998;

Charmaz, 2017).

Figure 1 presents this study’s sequential methodological design of the study, comprising three phases: 1st Phase (Scoping Review—yellow), 2nd Phase (Quantitative Study—green), and 3rd Phase (Qualitative Study—grey). The data collection instrument (pink) included the Health-Promoting Lifestyle Profile II (HPLPII) questionnaire by Nola Pender (blue) and semi-structured interviews (light blue). This design integrated quantitative and qualitative approaches, contributing to a deeper theoretical and practical understanding of the lived reality of informal caregivers in the post-caregiving period.

Inclusion criteria: individuals who had been the main caregiver for a dependent person, and whose caregiving role ended at least 12 months earlier following the death of the person cared for.

3. Results

The demographic profile of the qualitative sample—primarily female caregivers (8 out of 11), with a mean age of 60.2 years (range: 55–81), and predominantly adult children (6 daughters, 2 sons, 1 daughter-in-law, 1 wife, and 1 husband) caring for their parents—likely influenced the nature of the reported experiences and health promotion behaviors. These characteristics reflect traditional caregiving roles often assumed by middle-aged women, which may have shaped participants’ perceptions of responsibility, stress, and self-care practices. Furthermore, most participants were unemployed (7) or had left their jobs (2) or were on license (2) to provide care, indicating a socioeconomic profile that may have affected their access to resources and coping strategies. Although all participants resided in the Azores, efforts were made—aligned with the principles of Grounded Theory—to include variation in gender, age, caregiver roles, and employment status, ensuring a broad range of caregiving experiences. Despite this diversity, data saturation was reached, as participants expressed notably consistent perceptions and patterns regarding their caregiving experiences. This convergence suggests a shared understanding of caregiving within the studied context, supporting the theoretical robustness of the findings.

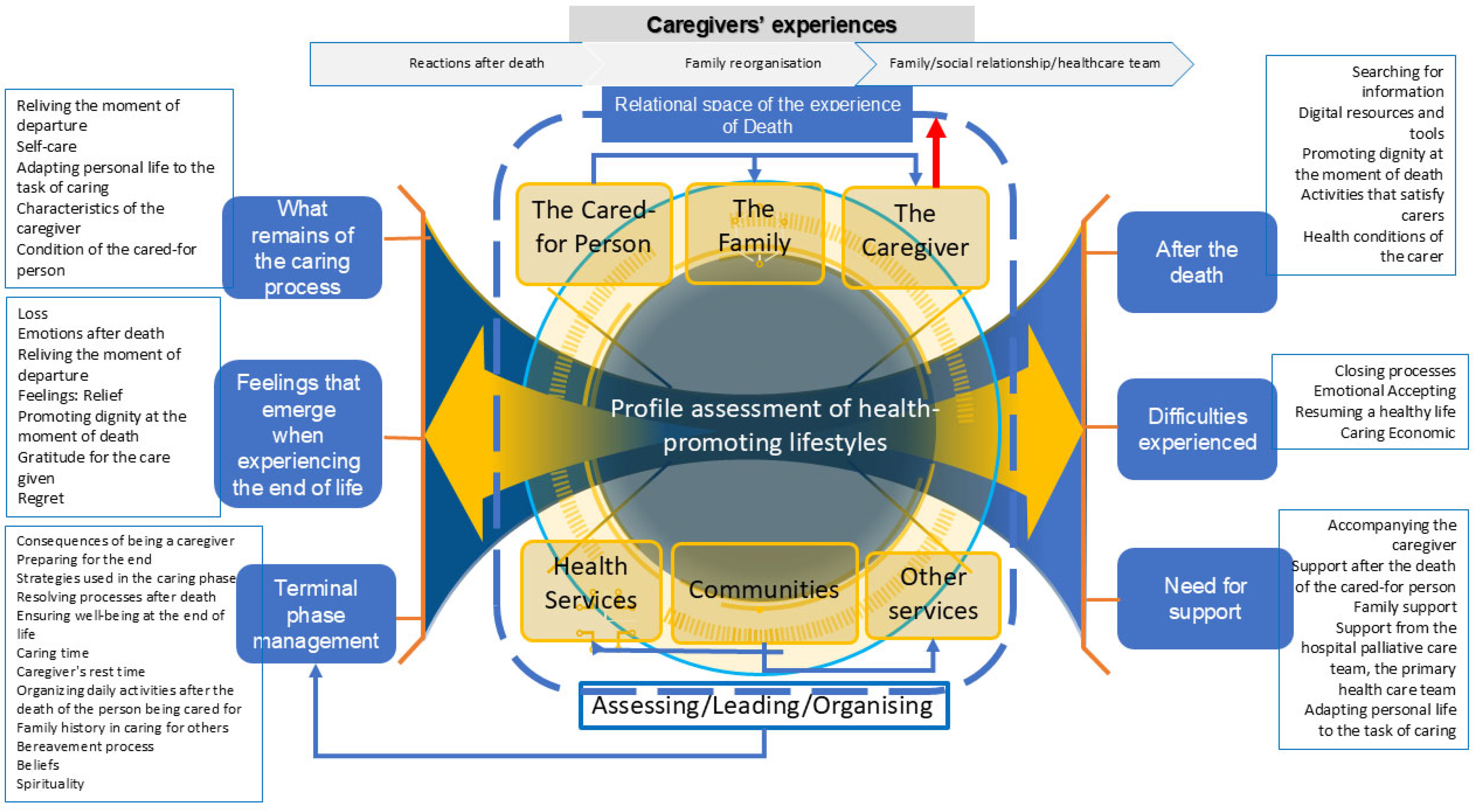

Based on the results of the studies, the Model of Experiences and Needs of Post-Caregivers in the End-of-Life Process and Reorganization after the death of the person being cared for emerged (

Figure 2), representing the flow of experiences of the main informal caregivers in the context of end-of-life care. The findings are structured into seven interconnected themes, reflecting the Model of Experiences and Needs of Post-Caregivers in the End-of-Life Process and Reorganization. These themes are not linear stages but interwoven experiences, influenced by the relational dynamics between caregivers, families, healthcare professionals, communities, and services. It allows for the identification of 52 codes in total, grouped according to thematic similarities, frequency of mentions, or relevance to the participant’s experiences. The 52 codes were based on 723 recording units. The central axis of the model—health-promoting lifestyles—is both a result and a driver of experiences during and after caregiving.

Terminal Phase Management

This theme addresses the complex experience of informal carers when caring for loved ones at the end of life, involving four central dimensions: diagnosing the situation, organizing, leading, and evaluating.

Diagnosis includes family history, grief, and spirituality, which are fundamental to emotional resilience. As one participant reflected, “After my brother died and during the five years I looked after my mum, I clung to my brother and not to God, but to him” (E4), illustrating how personal loss and spiritual displacement may shape the emotional framework for caregiving.

Organizing care includes planning routines, ensuring comfort and managing time, including moments of self-care to avoid burnout.

Leadership emphasizes preparing for death, managing emotions and interacting with healthcare teams, making it easier to cope with loss. One caregiver expressed this sense of responsibility and emotional investment: “I experienced moments of anxiety, I can say it was from caring, but… that anxiety was to ensure that at the end of her life she had dignity, felt comfort and never felt alone, because that was my role” (E1).

Finally, the continuous assessment of the patient’s needs and one’s own limitations helps with decision-making and coping with bereavement. The interrelationship of these dimensions contributes to more effective care and a balanced bereavement process.

Feelings that Emerge in the End-of-Life Experience

Participants reported intense and ambivalent emotions such as sadness, fear, resignation, and even relief. These emotions were shaped by their prior relationship with the cared-for person, the course of the illness, and the level of support available. As one participant expressed, “… although it was accompanied by intense pain (…) I can say that I felt relief.” (E4), highlighting how the end of suffering can coexist with personal grief.

This theme cuts across all pillars and reflects the emotional center of the cogwheel, symbolizing how individual experience shapes the entire process. The non-linearity is evident in how these feelings fluctuate and resurface at different stages.

Some participants found meaning in small, intimate gestures, as illustrated by one caregiver: “The touch, being close, the kiss at the start… a way of being with my mum.” (E2). These acts not only provided comfort to the loved one but also offered the caregiver a sense of presence and connection during emotionally charged moments.

Others grappled with doubt and self-evaluation, questioning their role and actions throughout the journey: “I wonder if I could have done more…” (E1). This emotional residue often lingered beyond the caregiving period, influencing the grieving process and underscoring the importance of emotional support.

The presence and validation offered by health professionals can play a crucial role in alleviating such emotional burden, providing not only palliative guidance but also a compassionate framework for caregivers to process their experiences.

What Remains of the Care Process

Caregivers reflected on the legacy of caregiving, including acquired knowledge, personal transformation, and a sense of continuing responsibility. While some experienced identity loss, others discovered resilience and new meaning through the caregiving experience. One participant encapsulated this transformation by stating, “I felt sad especially when I was doing something she liked. It was hard, but now I don’t remember her with pain. I miss her, but it’s no longer that longing of sorrow with pain. My mother’s death made me reflect and think that I wasn’t born into this family by chance, because I was destined to look after my father, grandfather and mother” (E1). This reflection highlights the intertwining of family history, caregiving legacy, and personal growth.

This theme highlights post-caregiver identity reconstruction. The cogwheel metaphor applies here as caregivers begin to reconnect with themselves and their surroundings, a process deeply influenced by their interactions with health services and support systems. The lingering connection to the cared-for person also manifests in symbolic objects and routines, as another participant shared, “I still have the last book my mum read.” (E2). Such mementos offer continuity and comfort in the identity transition.

Furthermore, this stage can mark the beginning of self-reclamation and health-promoting behavior. As one caregiver described, “I was able to find ways to maintain my social life and look after myself” (E6), reflecting a conscious effort to reestablish balance and well-being.

This moment of reorganization represents a crucial node for planning interventions that promote personal agency, resilience, and long-term psychological adaptation after caregiving ends.

Relational Space of the Death Experience

The experience of death is framed relationally, involving interactions between family members, health professionals, friends, and spiritual beliefs. Rituals, memories, and the enduring presence of the deceased in daily life are central aspects of this experience. As one participant expressed, “The absence is still here (…) I celebrate mass every month” (E3), highlighting how spirituality and ritual practices help maintain a meaningful connection with the deceased.

This theme lies at the top of the model, representing the web of relationships. It underscores that death is not just a clinical event but a profound social and emotional transition. The involvement of health professionals was seen as deeply impactful by some participants. One shared, “Words cannot describe how professional, friendly and available they were. Even though it was only an hour, their willingness to give us a call, to be able to go there, which was still a long way away, every day, I have no words” (E4). This reflects how compassionate care and presence from healthcare teams become embedded in the grieving memory.

Participants also described relational shifts and coping mechanisms following the loss. One noted, “Okay, I’ll be honest, I isolated myself a bit from my family and got very attached to my mum. Because at that moment it was my mum who needed it…” (E1), revealing how the caregiving bond can momentarily reconfigure other relationships.

In the aftermath, individuals adopt diverse strategies to manage grief. As E2 shared, “… I couldn’t sit on the sofa and cry and do nothing” and added, “I thought I needed to occupy my mind and I went to the office, my colleagues wanted me to stay at home for a few more days, but I preferred to go to work. I didn’t book any meetings those days, but I started working straight away. I thought I needed to occupy myself.” These accounts illustrate the urgency to regain a sense of control and routine, while still navigating the emotional impact of loss.

Healthcare professionals and communities must recognize and engage with these relational and symbolic aspects, offering space for ritual, memory, and emotional expression, which are key to supporting grief processing and identity reconstruction.

Difficulties Dealt

After death, caregivers face challenges such as social isolation, financial instability, and disruption of routines. Emotional exhaustion and lack of immediate support often delay the grieving process and hinder recovery. One caregiver reflected this lingering emotional presence, “Even today, sometimes it feels as if she’s here next to me and I find myself talking to her.” (E3) This illustrates how grief can blur the boundaries between past caregiving and present absence.

These difficulties reveal the fractures in the post-caregiving continuum. This pillar is cyclical—it often pulls caregivers back into emotional turmoil, especially when support systems, including healthcare, fail to respond adequately. One participant described the sense of life unraveling after the caregiving role ended, “), showing how fragile the post-caregiving period can be in the absence of sustained support.

The routine of revisiting familiar places also reveals the emotional ties that persist. As one caregiver shared, “At the weekend when I go to the Monasteries, I first go into the house, open the windows to air the house and then go to the cemetery.” (E4) These rituals not only preserve memory but also speak to the difficulty in fully detaching from the caregiving role.

This theme directly connects to the Need for Support pillar, and highlights the non-linear nature of the model, where recovery is neither immediate nor guaranteed. Continued engagement, recognition, and structured support from the health system are essential to help former caregivers navigate this complex transition and avoid prolonged emotional dislocation.

After Death and Bereavement

After the death of their loved one, informal carers experience ambivalent feelings such as relief, sadness, gratitude, and the need for personal reorganization. Acceptance of death often comes with a sense of mission accomplished, the perception of a dignified dying process, and the peace of knowing that suffering has ended. One caregiver reflected, “I felt a sense of peace… I treated my mother-in-law with a lot of love and affection” (E6), showing how compassionate caregiving can facilitate emotional closure.

However, this peace is frequently accompanied by a sense of emptiness and disruption, as the same participant noted, “I missed her, my routine with her, looking after her…” (E6), underscoring how caregiving becomes a core part of daily life and personal identity. The reconstruction of this identity and the reframing of everyday routines pose significant challenges in the post-caregiving period.

These moments are often marked by emotional fatigue and lack of motivation. One participant admitted, “…in the early days I confess I didn’t feel like doing anything” (E7), revealing how grief may temporarily paralyze efforts to reengage with life. In this context, access to quality end-of-life care can ease the emotional weight of loss, as another participant shared, “Excellent palliative care that we have in hospital” (E2), suggesting that structured, compassionate care can contribute to a more peaceful bereavement process.

Digital strategies emerge as helpful tools in this stage, supporting adaptation, reducing isolation, and facilitating access to information. Digital literacy is increasingly viewed as valuable—not only for accessing resources but also for providing emotional support and empowering former carers in the transition toward new personal goals.

Need for Support

A recurring theme is the lack of structured support, both formal (healthcare and legal) and informal (family and friends). Participants call for psychological support, reintegration into community life, and practical guidance post-care. This is the connector theme, interlinking all others. It demonstrates that support is needed before, during, and after death, reinforcing the cyclical nature of the model. Healthcare professionals are key facilitators of this support, coordinating across services and life stages.

While some participants reported finding valuable professional support—as one noted, “I found a team of professionals in palliative care. In fact, I say, I always say this without any favour and without any exaggeration, I found a team of very well prepared, very capable nurses, with a very caring human side” (E2)—others highlighted a sharp decline in their own well-being due to a lack of continued assistance. One participant recounted how physical and emotional symptoms emerged shortly after the loss: “I stayed at home for a few days, but then I went to work, but it was only for a short time as I immediately fell ill. After my mother-in-law died, my health problems started to appear, something serious…” (E6).

Additionally, the emotional isolation following bereavement was a common experience: “…in the first year, yes, I isolated myself a lot from people, until I managed to gain strength…” (E1). These narratives underscore the essential need for sustained, multidimensional support systems that accompany individuals through all phases of caregiving and grief.

The model is part of a broad process that includes the family, health services, and the community, as well as the difficulties and support needs faced after the death of the person being cared for. The model highlights the relationship between the cared-for person, the family, the caregiver, health services, communities, and other services within an assessment of health-promoting lifestyles.

Health professionals mediate these three pillars to assess, lead, and organize the care provided and the adequacy of the different responses to the needs of the patient/family and caregiver to guarantee dignity at the moment of death.

The center of the model, “Profile assessment of Health-Promoting Lifestyles”, is represented by a cogwheel, suggesting that all the actors in the process (patient/family/caregiver/health professionals/community/other services) are associated and interact with each other, influencing and being influenced by the caregiver’s life process and the end of life of the person being cared for around a common axis, which is the health-promoting lifestyle. This reflects the complexity of the care provided and the experience of death, where each element plays a fundamental role in the experience of the caregiver and the family. Also, it allows us to understand the individual and contextual factors that influence the adoption of healthy behaviors after the death of the person being cared for when the post-caregiver now has the time they did not have before to think about and take care of themselves. It provides support for more effective interventions and indicates that the well-being of those involved (the person being cared for, the family, the caregiver, and the community) is an essential factor in understanding which environmental conditions impact decision-making in behavioral changes to adhere to healthy lifestyles after the caregiving task has ended.

After having been responsible for the health or personal care of a loved one, the caregiver faces a period of transition when this task is over. Post-caregivers often find themselves in a scenario where after the caregiving process is over, they can refocus on themselves and adopt healthier habits. However, the ability to adopt and maintain healthy lifestyles depends on several factors. Most informal caregivers face a great deal of physical and emotional strain during the time they are caring. This fatigue can lead to burnout on the caregiver’s part, making initiating new activities or lifestyle changes difficult. Even though they now have more time for themselves, the post-caregiver can feel exhausted and unmotivated to adopt healthy habits due to the accumulated stress. During the caregiving period, many caregivers find their identity very much centered on the task of caring, which can lead to a sense of loss of purpose after this responsibility has ended. At this point, the post-caregiver may struggle to find a new focus or goal, making it challenging to dedicate themselves to their well-being. This transition requires psychological and emotional support to help the individual reconnect with their needs and desires. Post-caregivers may not have acquired healthy habits during the care period, especially if the priority was the well-being of the person being cared for, and may not know how to start or maintain a healthy routine. Eating, exercise, and self-care habits may have been neglected. In this case, the person needs guidance to look after themselves. After the caregiving task has ended, the post-caregiver may feel guilt or sadness about the absence of the person being cared for, which can affect their motivation to take care of themselves.

This is an opportunity for the post-caregiver to re-evaluate their life and prioritize their health. Now, with more time on their hands, the post-caregiver may be better able to plan and seek help, provided they can overcome the emotional difficulties mentioned. Support networks, such as friends, family, and caregiver support groups, can make a significant difference in adapting and resuming healthy habits. This can include incentives for physical exercise, seeking professional help with mental health management and adopting new routines.

4. Discussion

The experience of informal caregivers during their end-of-life journey, assisted bereavement, and reorganization to life after the caregiving task has ended is characterized by intense emotional and physical challenges. Caregivers often experience ambivalent feelings, alternating between guilt and hope.

The death of the person being cared for leads to a reassessment of daily routines. This can be challenging, as caregivers must adapt to a new normal without their loved ones (

L. Sousa et al., 2022).

During the terminal phase, caregivers deal with an overload of responsibilities, including providing comfort and relief care and administering medication and emotional support to their loved one. They often face feelings of helplessness, exhaustion, and anguish when witnessing the suffering of the person they are caring for, as well as challenges related to reconciling their personal and professional needs. At the end of the care period, many caregivers experience a profound sense of loss of identity and face social isolation and difficulties in reintegrating their personal and professional lives (

Roth et al., 2015;

C. I. C. Afonso, 2021).

Social and psychological support is essential to help them process this loss and rebuild their lives after such an intense period of dedication.

They face the pain of losing the person they cared for and the loss of the central role they occupied in their daily routine during the period of care (

Mora López, 2017).

The adaptation of the post-caregiver involves reconstructing the new phase of life, a transition process characterized by the acceptance and processing of the loss and the need to redefine their daily lives. This can involve a period of identity reconstruction, in which the post-caregiver seeks to recover neglected personal interests, leisure activities, and social relationships (

C. I. C. Afonso, 2021).

Adapting to the new stage of life is described as a gradual path, where the post-caregiver needs to find a new balance between their personal and social life while dealing with contradictory feelings, such as relief at the end of their loved one’s suffering coupled with guilt or uncertainty about how to resume “normal” life. As other authors have described, this process is not linear. It varies from person to person, depending on their relationship with their loved one, their family, social and professional support networks, and the emotional resources they have at their disposal (

C. I. C. Afonso, 2021). Support from outside the family can help ease the transition, although not all post-caregivers have adequate access to these networks. The grieving and adaptation process of the post-caregiver is described as a complex journey of transformation in which individuals are challenged to reconstruct their sense of self and their place in the everyday world after the loss of the caregiver role (

Mora López, 2017;

C. I. C. Afonso, 2021).

Beliefs and spirituality play a crucial role in how caregivers cope with death and bereavement. For many people, spirituality and religious beliefs offer solace, meaning and hope during the end-of-life and bereavement process. These elements are fundamental in helping family members deal with grief and loss, providing a perspective of transcendence and a deeper understanding of the cycle of life and death (

Barbosa, 2013).

In the context of bereavement, spirituality is seen as a resource that can help family members integrate the experience of loss in a less traumatic way, relieving emotional suffering and offering help in continuity, both in a spiritual sense and in remembering the person who has died. Authors recognize that palliative care professionals must be attentive to the spiritual needs of family members, providing adequate support that respects individual beliefs (

Barbosa, 2013;

Aparício et al., 2015).

Healthcare teams, especially nurses, play a fundamental role in assisted bereavement. They offer humanized support to terminally ill patients and their informal caregivers. Their work goes beyond clinical care to include emotional support, effective communication, and guidance on the death and bereavement process, promoting a dignified farewell to life.

In the post-loss period, the team can contribute to the grieving process of post-caregivers by referring them to support networks, support groups, or specialized services, minimizing the impacts of bereavement.

Family relationships with the main informal caregiver after the loss of the person being cared for point to different dynamics that can occur during this period. Studies suggest that the main informal caregiver, after the death of the person being cared for, goes through a complex transition phase that affects their family relationships (

Corey & McCurry, 2018).

In some cases, the caregiver may experience emotional relief and stress reduction, which can lead to an adaptation and strengthening of family ties that had been neglected during the caregiving period (

C. I. C. Afonso, 2021;

Corey & McCurry, 2018).

The caregiver may also face social isolation, especially if their identity and routine are strongly linked to the task of caring. The end of this role can bring a sense of loss of purpose, making it difficult to reintegrate into family and social relationships. Family support and open communication are essential for rebuilding relationships and the caregiver’s well-being (

Holdsworth, 2015).

The complexity of the relationship between the nursing team and informal caregivers in the context of family care is evidenced when nurses collaborate with informal caregivers, identifying significant benefits in the quality of life of caregivers and the person being cared for. This support ranges from home visits by health professionals for guidance to developing educational programs to train caregivers to deal with specific care situations and reduce feelings of isolation and emotional exhaustion (

Bagnasco et al., 2020).

Interaction between the healthcare team, particularly home care and palliative care nurses, and informal caregivers is essential to promote a more sustainable care environment. Training and emotional support are fundamental, as many caregivers face psychological and physical challenges that can be alleviated with regular guidance from health professionals. In addition, introducing formal support strategies, such as social and psychological support services, is key to mitigating burnout, especially during intense periods of caregiving (

Zarit & Zarit, 2015;

Teles et al., 2022;

Nasco, 2022).

The relationship between nurses and informal caregivers has the potential to minimize negative impacts, promoting more humanized and collaborative care that integrates the well-being of the patient and the informal caregivers themselves. This partnership also facilitates the development of public policies that meet the needs of caregivers and their families (

Nasco, 2022).

The relationship with the healthcare team is often described as family-like, “excellent, good friends, very good people, very professional,” and that they “form a family”. The accessibility and availability of the home care team have created a friendship between the post-caregivers that is characterized as part of the family.

The relationship with the healthcare team was marked by strong emotional support, a feeling of family, accessibility, and gratitude. The study participants deeply valued the role the team played in their lives during times of great difficulty and bereavement.

Promoting the health of caregivers emerges as a fundamental objective, seeking to minimize the negative impacts of assisted bereavement and encourage adaptation to the new reality. The Health Promoting Lifestyles Profile Assessment suggests that support should favor the well-being of post-caregivers and family members. Implementing actions that promote the health and well-being of post-caregivers, ensuring they have access to psychological support, social networks, and appropriate health services, facilitates adherence to healthy lifestyles that are partly forgotten when caring.

The theoretical model thus proposes an integrated view of care in the terminal phase and support for caregivers after their role has ended. It articulates the individual, family, and social factors involved in the end-of-life experience, suggesting a structured approach to minimizing the impacts of bereavement and promoting the health of those involved.

The model suggests that health policies should integrate caregivers during and after the task of care into the areas covered by end-of-life care. This means that health services should seek to accomplish the following:

- -

Implement programs to continuously assess the well-being of post-caregivers for as long as the team deems it necessary;

- -

Create emotional and psychological support strategies for the bereaved during the care process;

- -

Facilitate coordination between health services and social responses, promoting continued care after the death of the person being cared-for.

This model presents a systemic and integrated view of care in the terminal phase, highlighting the interrelationship between the actors involved. It also highlights the continuing impact of care, even after the death of the person being cared for, and the need for support for caregivers.