1. Introduction

Dermatological disorders are often accompanied by a negative body image, feelings of shame that affect patients’ relationships with others, low self-esteem, and emotional difficulties (

Dalgard et al., 2018;

Dunn et al., 2011;

Fox et al., 2007;

Khoury et al., 2014;

Nazik et al., 2017;

Uslu et al., 2008). Further evidence suggests that the visibility and localization of dermatological disorders significantly impact psychological outcomes, including self-esteem, body image, perceived social support, and psychological distress (

Al-Tarawneh & Al Tarawneh, 2024;

Magin et al., 2006). Visible skin conditions, such as acne, often lead to heightened self-consciousness and social anxiety, as individuals fear negative evaluations from others, resulting in lower self-esteem and increased psychological distress (

Al-Tarawneh & Al Tarawneh, 2024;

Magin et al., 2006). Conversely, individuals with less visibly prominent skin conditions like psoriasis or eczema may still experience substantial internalized stigma and emotional burden, particularly when symptoms flare unpredictably, leading to feelings of isolation and decreased perceived social support (

Kimball & Linder, 2013;

Schmid-Ott et al., 2007). Moreover, the chronic nature and perceived uncontrollability of such skin disorders, whether visible or not, have been linked to elevated levels of overall psychological distress, underscoring the need for holistic care that addresses both physical and psychological dimensions of dermatological conditions (

Dalgard et al., 2015). Although existing research has contributed valuable insights into the emotional difficulties experienced by individuals with dermatological conditions (

Datta et al., 2015;

Gupta & Gupta, 1998;

Hinkley et al., 2020;

Koo, 1995;

Magin et al., 2008), the majority of studies have examined these challenges in isolation, without adopting a comprehensive approach to general psychopathology. Furthermore, limited attention has been given to identifying psychosocial factors that may mediate the relationship between dermatological disorders and overall psychological distress. To address these methodological gaps, the present study examines the mediating role of psychosocial factors in the relationship between different types of dermatological conditions (e.g., acne, eczema, or psoriasis) and psychological distress.

Another factor that affects the well-being of dermatological patients is negative social experiences (

Magin et al., 2008). In the qualitative study by

Magin et al. (

2008), which examined the experiences of bullying and teasing in patients with acne, psoriasis, and eczema, the study focused on the role of bullying and appearance-related teasing as mediators of psychological morbidity in these patients. The results showed that patients who had experienced bullying or appearance-related teasing linked their experiences to the development of psychological difficulties, with effects on their self-image and self-esteem. Although the findings of this study were based on semi-structured interviews with 62 patients, they highlight the role of social support in the lived experience of dermatological disorders and patients’ psychological morbidity. Social support has been widely recognized as a crucial psychosocial resource in managing chronic health conditions, including dermatological disorders. In this context, social support refers to the extent to which patients perceive significant others—such as family members, partners, or close friends—as reliable sources of emotional, practical, and instrumental assistance. Importantly, social support plays a dual role for individuals with dermatological conditions, influencing both psychological adjustment and overall well-being. As highlighted in our previous study (

Costeris et al., 2021), significant others function as a protective factor, buffering the effects of stress and mitigating the intensity of psychological symptoms. These findings underscore the importance of incorporating supportive social networks into clinical interventions for dermatological patients, especially those experiencing appearance-related distress. On the other hand, negative experiences of bullying and teasing appear to be significant factors that intensify psychological morbidity in adolescents and children with acne, psoriasis, and eczema. Similarly, in the study by

Łakuta et al. (

2016), social stigma experiences, maladaptive beliefs about appearance and their projections onto self-evaluation, along with negative emotional attitudes towards the body, were found to fully mediate the relationship between the presence of skin lesions in psoriasis patients and depressive symptoms.

Additionally, the study by

Gupta and Gupta (

2013) on 312 participants without dermatological disorders in Canada examined the relationship between dissatisfaction with skin-related body image (i.e., the mental perception of one’s skin and its extensions, such as hair and nails) and suicidal ideation. It also explored the mediating effect of interpersonal sensitivity. The study found an inverse relationship between satisfaction with skin-related body image and suicidal ideation, which was mediated by interpersonal sensitivity. Based on these findings, the mediating effect of interpersonal sensitivity, which is a dimension of symptoms such as feelings of inferiority and inadequacy toward others, as well as discomfort during interpersonal interactions (

Derogatis & Melisaratos, 1983), may explain the effect of social alienation on suicide risk, even in a non-clinical population sample.

Similar findings were reported in the study by

Pereira et al. (

2017) on patients with dermatological tumors, where body image mediated the relationship between cognitive and perceptual representations of illness, family-related stress, psychological morbidity, and quality of life.

Furthermore, the study by

Łakuta and Przybyła-Basista (

2017) with 193 psoriasis patients in Poland found that the age of psoriasis onset moderated the impact of dermatological disorder on social anxiety. Specifically, for patients whose dermatological disorder onset occurred before adulthood, higher disease severity was associated with higher levels of social anxiety. Findings also showed that body-related negative emotions mediated the relationship between psoriasis severity and depressive symptoms. Additionally, the relationship between psoriasis severity and body-related emotions was moderated by patients’ gender. In this study, we focused on evaluating patients’ body image and overall self-esteem. To investigate patients’ comprehensive self-esteem and their overall perception of personal worth, we used one of the most reliable and valid instruments available in psychological research.

Taken together, these studies underscore the significant role of body image, social experiences, and self-perception in shaping the psychological outcomes of dermatology patients. They also highlight the need for further research into the mechanisms that mediate the link between dermatological disorders and overall psychological distress.

Current Study

The present study is among the first to examine the mediating roles of perceived social support, appearance satisfaction, and global self-esteem in the relationship between the type of dermatological condition (visible acne vs. non-visible eczema or psoriasis) and psychological distress among patients with skin disorders. It specifically investigates how these psychosocial variables may serve as mechanisms through which the effects of dermatological diagnosis, whether primarily visible or not, impact psychological distress. By identifying these mediating pathways, the study underscores the importance of integrating psychosocial considerations into both the assessment and treatment of dermatological conditions to prevent or alleviate associated psychological difficulties.

It is hypothesized that perceived social support, appearance satisfaction, and overall self-esteem will significantly mediate the relationship between dermatological diagnosis and psychological distress, such that higher levels of these protective factors will attenuate the negative psychological outcomes associated with skin disorders. More precisely, it is assumed that these mediating variables fully account for the relationship between the dermatological group (acne, eczema, or psoriasis) and psychopathology. This hypothesis is considered novel, as existing literature lacks mediation studies examining how these psychosocial constructs influence the relationship between dermatological conditions and psychological outcomes.

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

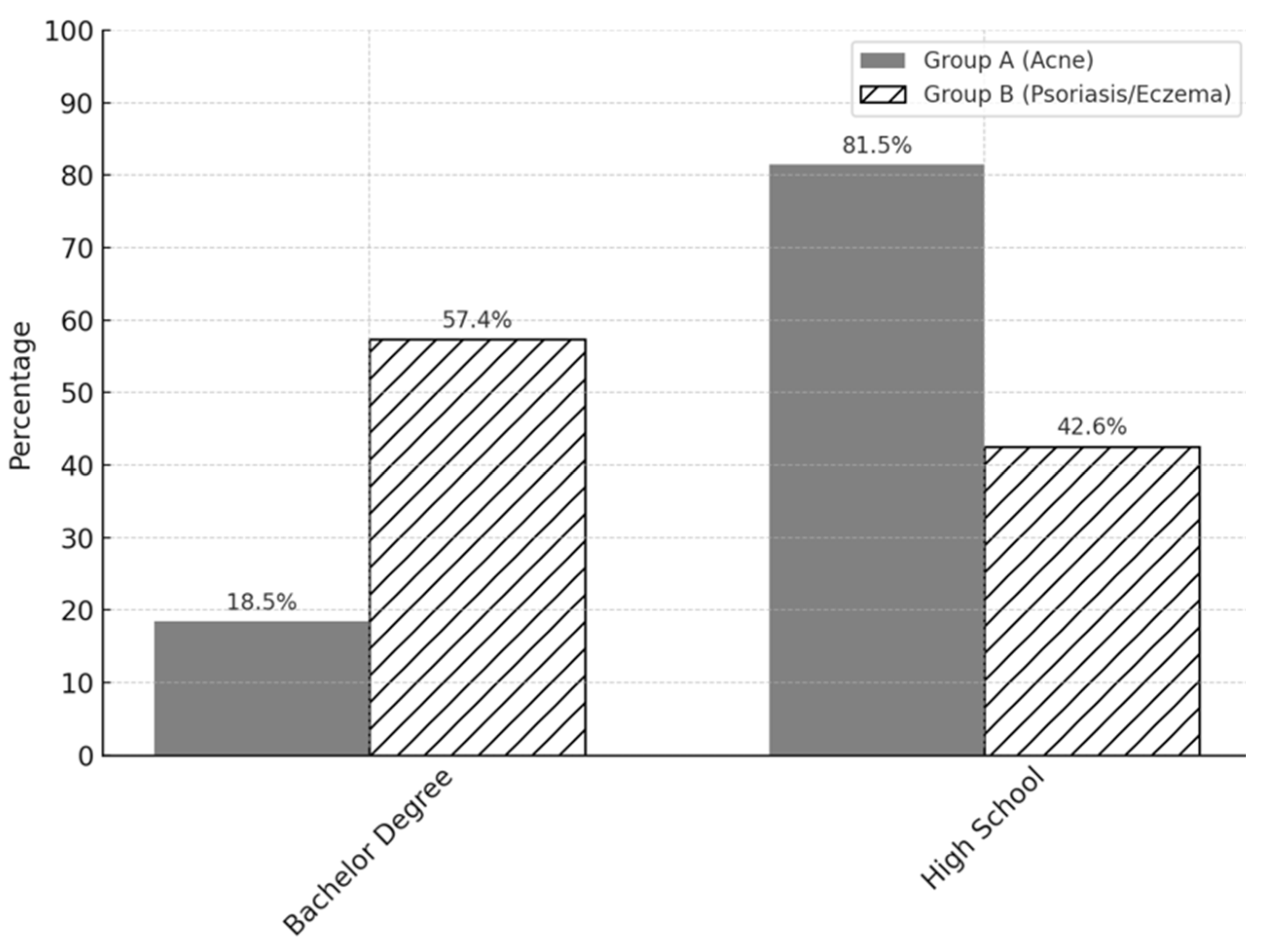

One hundred and eight patients (18~35 years) participated in the study, after being diagnosed by their physician, a dermatologist. In Group A, there were fifty-four participants (

n = 54) with visible facial cystic acne, and in Group B, there were fifty-four participants (

n = 54) with non-visible psoriasis or eczema. Their demographics are presented in

Figure A1,

Figure A2,

Figure A3 and

Figure A4 in

Appendix A, which summarize the characteristics of both groups.

3.2. Perceived Social Support, Appearance Satisfaction, and Self-Esteem as Mediators in the Relationship Between the Group of Dermatology Patients and the Overall Psychological Distress (GSI)

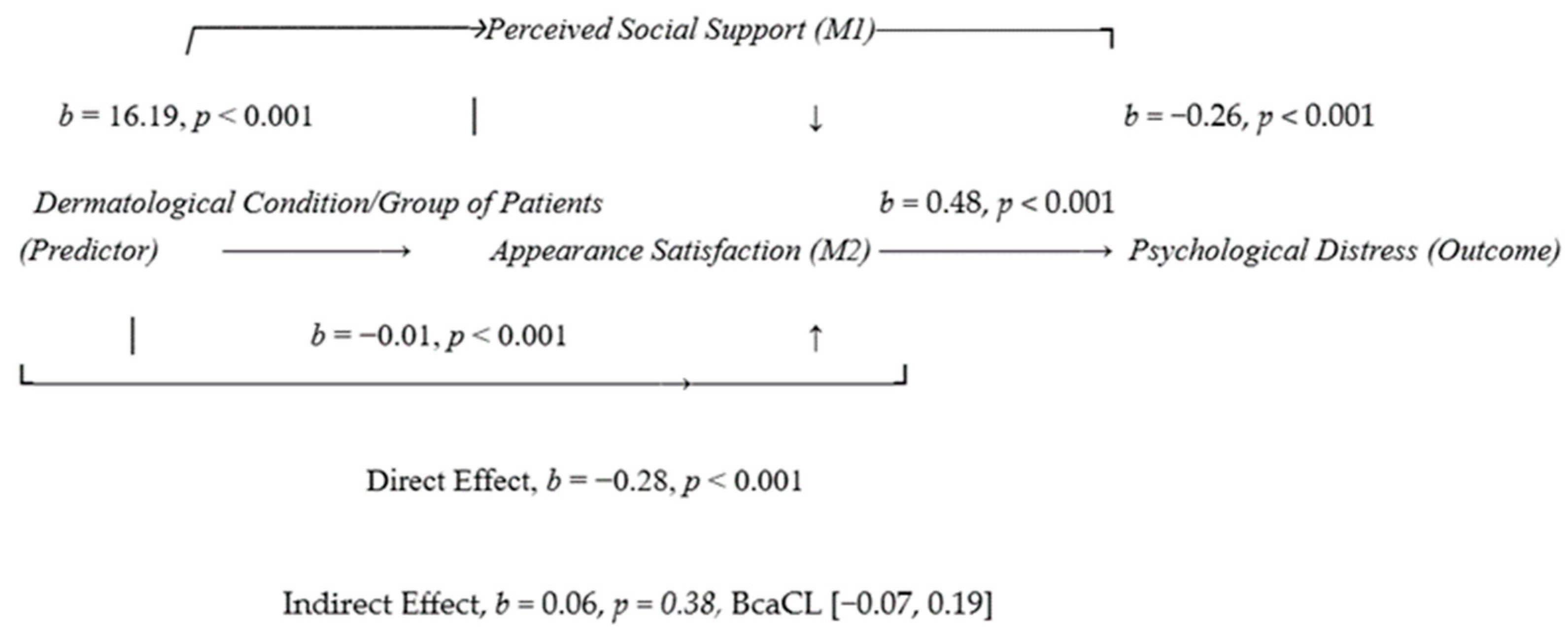

In this analysis, the independent variable is the group to which the dermatology patient belongs, the dependent variable is the overall psychological distress (GSI), and the mediating variables are the following three scales: overall perceived social support, overall satisfaction with external appearance, and overall self-esteem.

Results indicated that the direct effect of the group of dermatological patients on overall psychological distress (path c) is statistically significant,

b = −0.28,

p < 0.001, 95% CI

[−

0.38, −

0.18] (see

Table 1).

The effect of the group from which dermatological patients come from is statistically significant both for overall satisfaction with external appearance (path a1) with b = 0.48, p < 0.001, BcaCL [0.37, 0.59], and for overall self-esteem (path a2) with b = −0.84, p < 0.001, BcaCL [0.46, 1.23], but also for overall perceived social support (path a3) with b = 16.19, p < 0.001, BcaCL [13.73, 18.64].

Additionally, the effect of the first mediator on the dependent variable, controlling for the independent variable (i.e., the effect of overall satisfaction with external appearance on the overall psychological distress, controlling for the group of dermatological patients—path b1), is statistically significant with b = −0.26, p < 0.001, BcaCL [−0.41, −0.11].

The effect of overall self-esteem (path b2) is b = −0.01, p = 0.39, BcaCL [−0.04, 0.02], which is not statistically significant. The effect of overall perceived social support (path b3) is b = −0.01, p < 0.001, BcaCL [−0.02, −0.01], which is statistically significant.

Furthermore, the direct effect of the group of dermatological patients on the overall psychological distress, controlling for all three mediators (overall satisfaction with external appearance, overall self-esteem, and overall perceived social support—path c′), is with b = 0.06, p = 0.38, BcaCL [−0.07, 0.19], which is no longer statistically significant. Therefore, the conditions for confirming multiple mediation effects in the relationship between the group of dermatological patients and the overall psychological distress were met.

The total indirect effect (from the independent to the dependent variable through the mediators) is b = −0.34, BcaCL [−0.44, −0.25], which is statistically significant.

The aforementioned results indicate that there is a statistically significant influence of the group of dermatological patients on overall psychological distress, with overall satisfaction with external appearance

(b = −0.26, BcaCL [−0.41, −0.11]) and overall perceived social support

(b = −0.01, BcaCL [−0.02, −0.01]). Specifically, visible dermatological conditions are associated with higher psychological distress and lower overall satisfaction with external appearance. In summary, the overall psychological distress of dermatological patients is explained by the mediating effects of their perceived social support and satisfaction with their external appearance (

Figure 1).

4. Discussion

In this quantitative study on acne, psoriasis, and eczema in a sample of adult Cypriot population, we focused on patients who sought dermatological treatment. Most studies in the literature examine the factors influencing the levels of psychopathology in dermatological patients individually. In contrast, the current research investigates them as a multilevel phenomenon, using a methodological approach that has not been previously proposed: comparing two conditions of dermatological disorders. Specifically, this study developed a mediation model that included three mediators: overall perceived social support, overall satisfaction with external appearance, and overall self-esteem. The results revealed that overall satisfaction with external appearance and overall perceived social support have a mediating role in the relationship between the group of dermatological patients and their overall psychological distress.

The current study highlights that the type of dermatological disorder has a significant impact on patients’ perceived social support and psychological well-being. Our findings align with previous evidence suggesting that the visibility of dermatological conditions plays a crucial role in shaping psychological outcomes, including self-esteem, body image, perceived social support, and overall psychological distress (

Al-Tarawneh & Al Tarawneh, 2024;

Magin et al., 2006). Additionally, patients with less visibly prominent yet chronic conditions, such as eczema or psoriasis, may still face significant emotional strain and internalized stigma, especially during symptom flare-ups, which can lead to social withdrawal and diminished perceived support (

Kimball & Linder, 2013;

Schmid-Ott et al., 2007). Overall, these findings agree with those of

Dalgard et al. (

2015), which demonstrate that the persistent and unpredictable nature of these dermatological conditions, regardless of visibility, has been consistently linked to increased levels of anxiety and depression and highlight the importance of comprehensive treatment approaches that address both the physical and social aspects of dermatological care.

This study also underscores the importance of assessing the adequacy of social support throughout the progression of a dermatological condition. This study highlights the importance of evaluating the adequacy of social support throughout a skin disorder. Support groups for dermatological patients should be promoted when necessary. Furthermore, we conclude that a dermatological patient’s perception of their body directly influences their perception of their dermatological condition. Conversely, the presence of a dermatological condition negatively affects appearance satisfaction, which can subsequently impact the patient’s overall psychological distress and behavior. Since acne, psoriasis, and eczema commonly appear in early developmental stages (

Datta et al., 2015), examining how patients reevaluate their body image while accepting the dermatological alterations caused by the skin disorder plays a significant role in their psychological readiness to cope with the condition or adapt to it. Our findings align with studies by

Łakuta et al. (

2016) and

Magin et al. (

2008), which suggest that social support can protect dermatological patients psychologically. In contrast, the absence of social support, along with experiences of bullying and appearance-related teasing, which can be interpreted as social stigma, increases the vulnerability of dermatological patients to psychological difficulties.

Although our study did not focus on the quality of life of dermatological patients, the results of our study align with those of

Pereira et al. (

2017), emphasizing the critical role of appearance satisfaction and social support in the psychological well-being of patients with dermatological tumors. From the findings on both patients with dermatological tumors and patients with acne, psoriasis, and eczema, the need for psychological interventions targeting appearance satisfaction and social support becomes evident. These factors mediate the experience of dermatological disorder and the presence of high psychopathology levels, yet they remain underexplored in the literature. Assessing appearance satisfaction in dermatological patients using clinical psychological tools is of primary importance at the onset of dermatological treatment, as it can help identify psychologically vulnerable patients. Additionally, it is suggested that early identification of dermatological patients with lower appearance satisfaction can be addressed with the creation of psychological support groups, both for reframing misperceptions about body image and for serving as a protective factor against developing psychopathological symptoms.

Furthermore, the present study supports that lower appearance satisfaction mediates the relationship between the group of dermatological patients and overall psychological distress. Prior research has consistently shown that dermatological conditions, whether visibly apparent or not, can significantly impact individuals’ satisfaction with their appearance. Visible conditions such as acne, rosacea, or vitiligo are particularly associated with body image concerns due to their prominence in social interactions, often leading to diminished appearance satisfaction and increased self-consciousness (

Gupta & Gupta, 2013). However, even less visible skin disorders, such as eczema or psoriasis—especially when located on covered areas of the body—can negatively affect body image and satisfaction with appearance, particularly due to symptoms like itching, discomfort, or the anticipation of flare-ups. These concerns can lead individuals to internalize feelings of shame and inadequacy and experience psychological distress, regardless of whether others can see the condition (

Papadopoulos et al., 2000). Importantly, both visible and non-visible skin conditions have been linked to lower levels of appearance satisfaction, which in turn can mediate the relationship between the skin condition and broader psychological outcomes, including depression and anxiety.

Furthermore, our results align with those of

Łakuta and Przybyła-Basista (

2017). The key difference between these studies lies in the fact that the current study’s focus was on the overall psychological distress of patients, rather than on specific psychopathological elements. Additionally, this study did not find that gender moderated the relationship between the group of dermatological disorders and satisfaction with appearance. The primary reason for this discrepancy may be that the current study sample consisted of patients from two dermatological groups, with an equal number of men and women, whereas the study of

Łakuta and Przybyła-Basista (

2017) included a predominantly female sample (68.4% women vs. 31.6% men). This study reinforces the finding of

Łakuta and Przybyła-Basista (

2017) that negative emotions related to body image mediate the relationship between dermatological disorder and depression. By incorporating two dermatological patient groups, this study demonstrates that appearance satisfaction mediates the relationship between dermatological disorder and the overall psychological distress. Consequently, our study suggests that interventions aimed at improving body image and appearance-related coping may benefit individuals across a range of dermatological diagnoses.

Finally, the findings of this study are consistent with those of

Gupta and Gupta (

2013), underscoring the beneficial role of social support not only for individuals with dermatological conditions but also for the general population. Social support appears to facilitate psychological adaptation by reducing levels of psychopathology. Given that interpersonal sensitivity and feelings of social inadequacy are key contributors to psychological distress in non-clinical populations, our results underscore the importance of educating dermatologists on the psychosocial aspects of skin disorders. Specifically, social support should be recognized as a protective factor that can alleviate psychological burden among patients with acne, psoriasis, and eczema.

4.1. Limitations and Strengths

Given that the entire sample consisted of individuals actively seeking treatment from dermatologists, the findings of this study cannot be generalized to all individuals with dermatological conditions. Some patients may have already adapted to their condition, possess strong social support networks, and experience minimal concern regarding their physical appearance. Additional limitations include the relatively small sample size and the exclusive use of self-report measures, which may introduce response biases. While our study utilized an instrument designed to measure overall self-esteem, future research exploring sociometric self-esteem, i.e., patients’ self-evaluation based on their perceived value and acceptance by others, could determine whether it serves as a mediating factor between dermatological diagnosis and psychological distress.

Moreover, participants were recruited solely from two urban areas in Cyprus—Paphos and Limassol—further limiting the generalizability of the findings to the broader population of individuals with acne, psoriasis, or eczema across the island. Nevertheless, the sample represented the maximum number of patients that participating dermatologists were able to refer. The use of brief and accessible self-report questionnaires was intentionally chosen by the researchers to minimize participant burden, as patients were in a psychologically vulnerable state and on the verge of initiating pharmacological treatment.

Despite the limitations, this study is novel in several aspects. It is among the first to explore how multiple psychosocial factors concurrently mediate the relationship between distinct types of dermatological conditions and psychological outcomes. Notably, the study encompasses two prevalent and clinically distinct dermatological conditions, acne and eczema/psoriasis, and incorporates a comprehensive assessment framework that combines both dermatologists’ evaluations and patients’ self-reports. Utilizing reliable and standardized psychometric tools, this study provides a comprehensive approach to understanding the psychological impact of dermatological conditions. It has been proven that perceived social support and appearance satisfaction significantly mediate the relationship between dermatological conditions and psychological distress. Specifically, higher levels of these protective factors will attenuate the adverse psychological outcomes associated with skin disease.

4.2. Clinical Implications and Future Directions

This study offers valuable insights into the psychosocial mechanisms that link symptoms of dermatological disorders with their associated emotional and social dimensions. Specifically, it demonstrates that perceived social support and satisfaction with external appearance significantly mediate the impact of dermatological diagnosis on patients’ psychological well-being. These findings underscore the importance of addressing the physical symptoms of dermatological disorders, as well as their associated emotional and social dimensions.

From a clinical perspective, the results highlight the need for a more holistic and interdisciplinary approach to dermatological care. In collaboration with mental health professionals, dermatologists should be trained to recognize signs of psychological distress and understand the protective role of social support and body image satisfaction. Integrating brief psychosocial screenings into routine dermatological assessments, alongside medical treatment, may enhance patient outcomes. Additionally, developing patient-centered interventions aimed at improving self-esteem and fostering supportive social networks may help mitigate the psychological burden commonly experienced by individuals with conditions such as acne, psoriasis, and eczema.

Future research should replicate these findings in larger and more diverse samples across different cultural contexts to strengthen the generalizability of the results. Longitudinal studies are also necessary to investigate how the mediating roles of social support and appearance satisfaction evolve throughout treatment and disease progression. Furthermore, incorporating qualitative methodologies may offer deeper insights into patients’ lived experiences and coping mechanisms. Finally, intervention studies that test the efficacy of psychosocial programs—such as support groups, psychoeducation, or cognitive-behavioral strategies—could contribute to the development of integrated care models that better address the complex needs of dermatological patients.