Student Teachers’ Practice Self-Efficacy Prior to Their First Field Practice in Schools: Interrelatedness of Subconstructs Within Three Domains of Practice

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Relationships Between Self-Efficacy Dimensions Among Student Teachers

1.2. Student Characteristics with Possible Effect on Student Teachers’ Practice Self-Efficacy

1.2.1. Previous Teaching Experience

1.2.2. Admission Track

1.2.3. Major Teaching Subject

1.2.4. Gender

1.3. The Current Study

1.3.1. Context

1.3.2. Aims and Expectations

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and Data Collections

2.2. Instrument

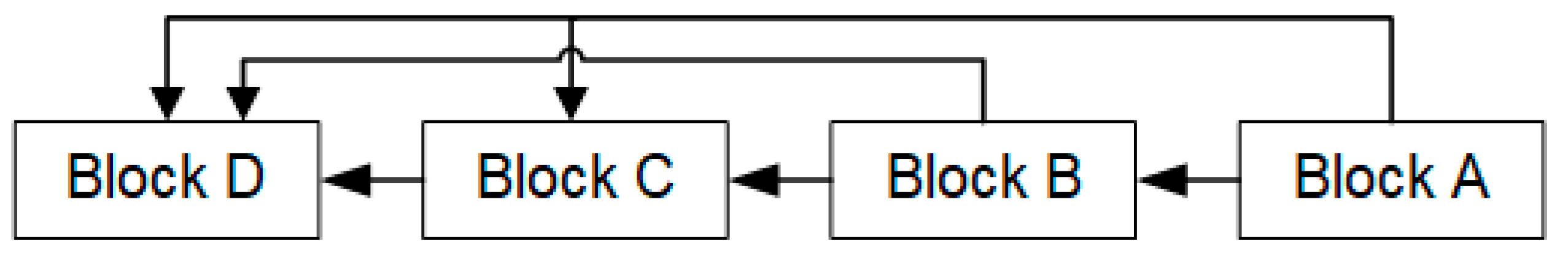

2.3. Analysis

3. Results

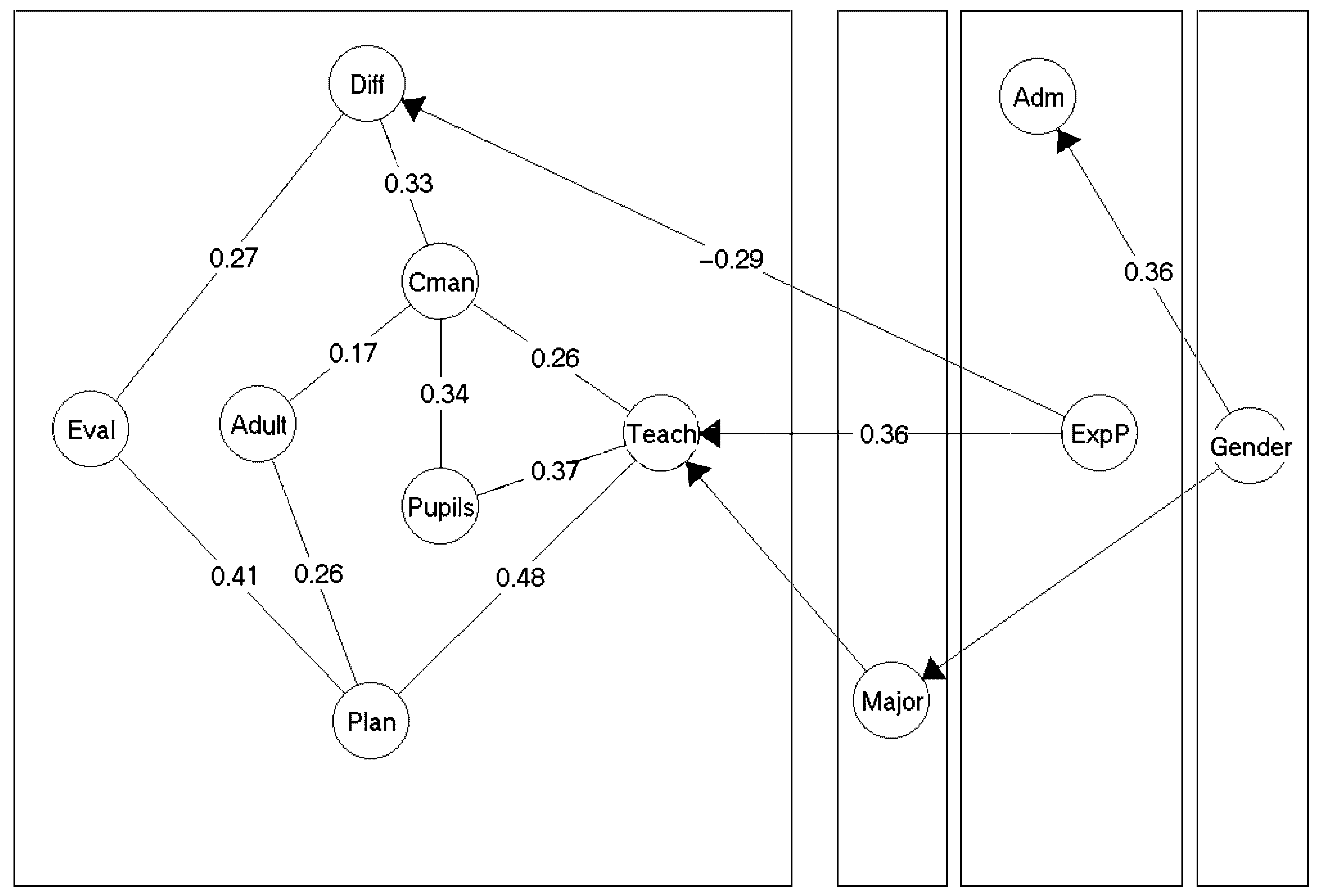

3.1. Associations Between PSE Scores

3.2. Conditional Dependence/Independence of PSE Scores on Background Variables

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Act on the Education of Teachers. (2024). Bekendtgørelse om uddannelsen til professionsbachelor som lærer i folkeskolen, BEK nr 707 af 11/06/2024. Available online: https://www.retsinformation.dk/eli/lta/2024/707 (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- Ashton, P. T., & Webb, R. B. (1986). Making a difference: Teachers’ sense of efficacy and student achievement. Longman. [Google Scholar]

- Avanzi, L., Miglioretti, M., Velasco, V., Balducci, C., Vecchio, L., Fraccaroli, F., & Skaalvik, E. M. (2013). Cross-validation of the Norwegian teacher’s self-efficacy scale (NTSES). Teaching and Teacher Education, 31, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bager-Elsborg, A., Herrmann, K. J., Troelsen, R., & Ulriksen, L. (2019). Are leavers different from stayers? Dropout and students’ perceptions of the teaching–learning environment. Uniped, 42(2), 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. Freeman. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini, Y., & Hochberg, Y. (1995). Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Methodological), 57(1), 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, D. A., Skaalvik, E. M., Asil, M., Hill, M. F., Uthus, M., Tangen, T. N., & Smith, J. K. (2023). Teacher self-efficacy and reasons for choosing initial teacher education programmes in Norway and New Zealand. Teaching and Teacher Education, 125, 104041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betoret, F. D. (2006). Stressors, self-efficacy, coping resources, and burnout among secondary school teachers in Spain. Educational Psychology, 26, 519–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgueño, R., Sicilia, A., Medina-Casaubón, J., Alcaraz-Ibañez, M., & Lirola, M. J. (2019). Psychometry of the teacher’s sense of efficacy scale in Spanish teachers’ education. The Journal of Experimental Education, 87(1), 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprara, G. V., Barbaranelli, C., Steca, P., & Malone, P. S. (2006). Teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs as determinants of job satisfaction and students’ academic achievement: A study at the school level. Journal of School Psychology, 44(6), 473–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, K. B., Kreiner, S., & Mesbah, M. (2013). Rasch models in health. ISTE & John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J., & Berlin, R. (2020). What constitutes an “opportunity to learn” in teacher preparation? Journal of Teacher Education, 71, 434–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, D. R., Spjøtvoll, E., Johansen, S., van Zwet, W. R., Bithell, J. F., Barndorff-Nielsen, O., & Keuls, M. (1977). The role of significance tests [with discussion and reply]. Scandinavian Journal of Statistics, 4(2), 49–70. [Google Scholar]

- Cristofori, I., Cohen-Zimerman, C., & Grafman, J. (2019). Chapter 11—Executive functions. In M. D’Esposito, & J. H. Grafman (Eds.), Handbook of clinical neurology (pp. 197–219). Elsevier. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J. A. (1967). A partial coefficient for Goodman and Kruskal’s gamma. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 62, 189–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Digitale, J. C., Martin, J. N., & Glymour, M. M. (2022). Tutorial on directed acyclic graphs. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 142, 264–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffin, L. C., French, B. F., & Patrick, H. (2012). The teachers’ sense of efficacy scale: Confirming the factor structure with beginning pre-service teachers. Teaching and teacher Education, 28(6), 827–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elstad, E., & Christophersen, K.-A. (2017). Perceptions of digital competency among student teachers: Contributing to the development of student teachers’ instructional self-efficacy in technology-rich classrooms. Education Sciences, 7(1), 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, G. (1995). Derivations of the Rasch model. In H. F. Gerhard, & W. M. Ivo (Eds.), Rasch models. Foundations, recent developments, and applications. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, L. A., & Wallis, W. H. (1954). Measures of association for cross classifications. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 49, 732–764. [Google Scholar]

- Gundelach, P., & Kreiner, S. (2004). Happiness and life satisfaction in advanced European countries. Cross-Cultural Research, 38(4), 359–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hans, A., & Hans, M. E. (2017). Classroom management is prerequisite for effective teaching. International Journal of English and Education, 6(2), 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugen, C. R., & Hestbek, T. A. (2015). Hensikter med lærerutdanning og ulike kunnskapsformer—Er integrasjon av pedagogikk og fagdidaktikk formålstjenlig? Utdanningsforskning.no. Available online: https://utdanningsforskning.no/artikler/2012/hensikter-med-larerutdanning-og-ulike-kunnskapsformer-er-integrasjon-av-pedagogikk-og-fagdidaktikk-formalstjenlig/ (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- Heneman, H. G., III, Kimball, S., & Milanowski, A. (2006). The teacher sense of efficacy scale: Validation evidence and behavioral prediction. WCER Working Paper No. 2006-7. University of Wisconsin–Madison, Wisconsin Center for Education Research. Available online: http://www.wcer.wisc.edu/publications/workingPapers/Working_Paper_No_2006_07.pdf (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- Howell, H., & Mikeska, J. N. (2021). Approximations of practice as a framework for understanding authenticity in simulations of teaching. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 53(1), 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C. (2013). Gender differences in academic self-efficacy: A meta-analysis. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 28(1), 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khairani, A. Z., & Makara, K. A. (2020). Examining the factor structure of the teachers’ sense of efficacy scale with Malaysian samples of in-service and pre-service teachers. Pertanika Journal of Social Science and Humanities, 28(1), 309–323. Available online: https://eprints.gla.ac.uk/212461/1/212461.pdf (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- Khine, M. S., & Nielsen, T. (Eds.). (2022). Academic self-efficacy: Nature, measurement, and research. Springer Nature. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H., & Cho, Y. (2014). Pre-service teachers’ motivation, sense of teaching efficacy, and expectation of reality shock. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 42(1), 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K. R., & Seo, E. H. (2018). The relationship between teacher efficacy and students’ academic achievement: A meta-analysis. Social Behavior and Personality, 46(4), 529–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klassen, R. M., Bong, M., Usher, E. L., Chong, W. H., Huan, V. S., Wong, I. Y., & Georgiou, T. (2009). Exploring the validity of a teachers’ self-efficacy scale in five countries. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 34(1), 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klassen, R. M., & Chiu, M. M. (2011). The occupational commitment and intention to quit of practicing and pre-service teachers: Influence of self-efficacy, job stress, and teaching context. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 36(2), 114–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klassen, R. M., & Tze, V. M. (2014). Teachers’ self-efficacy, personality, and teaching effectiveness: A meta-analysis. Educational Research Review, 12, 59–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klempin, C., Rehfeldt, D., Seibert, D., Mehrtens, T., Köster, H., Lücke, M., Nordmeier, V., & Sambanis, M. (2019). Realizing theory-practice transfer in German teacher education: Tracing preliminary effects of a complexity reduced teacher training format on trainees from four subject domains on students’ perception of ‘self-efficacy’ and ‘relevance of theoretical contents for practice’. Research in Subject-Matter Teaching and Learning (RISTAL), 2(1), 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klette, K., Hammerness, K., & Jenset, I. S. (2017). Established and evolving ways of linking to practice in teacher education: Findings from an international study of the enactment of practice in teacher education. Acta Didactica Norge, 11(3), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreiner, S. (1986). Computerized exploratory screening of large dimensional contingency tables. In F. De Antoni, H. Lauro, & A. Rizzi (Eds.), COMPSTAT. Proceedings in computational statistics (pp. 43–48). Physica Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Kreiner, S. (1987). Analysis of multidimensional contingency tables by exact conditional tests: Techniques and strategies. Scandinavian Journal of Statistics, 14(2), 97–112. [Google Scholar]

- Kreiner, S. (2003). Introduction to DIGRAM. Research Report 03/10. Department of biostatistics, University of Copenhagen. [Google Scholar]

- Kreiner, S. (2007). Statistisk problemløsning. Præmisser, teknik og analyse (2nd ed.). Jurist-og Økonomforbundets Forlag. [Google Scholar]

- Kreiner, S. (2014). A guided tour through DIGRAM 3.11. Analysis of contingency tables by chain graph models. Department of Biostatistics, University of Copenhagen. [Google Scholar]

- Kreiner, S., & Christensen, K. B. (2007). Validity and objectivity in health-related scales: Analysis by graphical loglinear Rasch models. In M. von Davier, & C. H. Carstensen (Eds.), Multivariate and mixture distribution Rasch models (pp. 329–346). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Kreiner, S., Petersen, J. H., & Siersma, V. (2009). Deriving and testing hypotheses in chain graph models. Research Report 09/09. Department of Biostatistics, University of Copenhagen. [Google Scholar]

- Lauritzen, S. L. (1996). Graphical models. Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lauritzen, S. L., & Richardson, T. S. (2002). Chain graph models and their causal interpretations. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series B (Statistical Methodology), 64(3), 321–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddux, J. E. (2002). Self-efficacy. In C. R. Snyder, & S. J. Lopez (Eds.), Handbook of positive psychology (pp. 277–287). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Makransky, G., Havmose, P., Vang, M. L., Andersen, T. E., & Nielsen, T. (2017). The predictive validity of using admissions testing and multiple mini-interviews in undergraduate university admissions. Higher Education Research & Development, 36(5), 1003–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muris, P. (2002). Relationships between self-efficacy and symptoms of anxiety disorders and depression in a normal adolescent sample. Personality and Individual Differences, 32(2), 337–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, T. (2022). Predicting student teacher’s academic learning self-efficacy at the second semester from their pre-academic learning self-efficacy. In J. J. Carmona (Ed.), The importance of self-efficacy and self-compassion (pp. 1–32). Nova Science Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, T., Fellinghauer, C., Strobl, C., Kronthaler, D., & Kreiner, S. (2025). Statistical anxiety and attitudes towards statistics in psychology students: A measurement comparison study of the German and Danish language versions of the HFS-R. Educational Methods & Psychometrics, 3, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, T., Lindemann, D. M., Toft, L., Pettersson, M., Nielsen, E. H., Jensen, L. S., & Larsen, G. G. (2024a). Teacher and teaching-related practices student teachers may have difficulty believing they can enact/engage in while in field practice: Perspectives from student teachers and teachers in field-practice schools. Nordic Studies in Education, 44(2), 103–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, T., Makransky, G., Vang, M. L., & Dammeyer, J. (2017). How specific is specific self-efficacy? A construct validity study using Rasch measurement models. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 53, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, T., Martínez-García, I., & Alestor-García, E. (2021). Critical thinking of psychology students: A within-and cross-cultural study using Rasch models. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 62(3), 426–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, T., & Pettersson, M. (2025). Praksis self-efficacy for lærerstuderende (PSEQ). Spørgeskema, scoringsguide og administration. UCL Erhvervsakademi og Professionshøjskole. ISBN 978-87-93067-71-4. Available online: https://www.ucviden.dk/da/publications/praksis-self-efficacy-for-l%C3%A6rerstuderende-pseq-sp%C3%B8rgeskema-scorin (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- Nielsen, T., Pettersson, M., Toft, L., Lindemann, D. M., & Nielsen, E. H. (2024b). Development and initial validation of the Practice Self-Efficacy Questionnaire (PSEQ) for student teachers. Educational Methods & Psychometrics, 2, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, D. L., & Nielsen, T. (2024). Admission testing, pre-academic exam self-efficacy, and retention: A prospective cohort study. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 83, 101383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pajares, F. (1996). Self-efficacy beliefs in academic settings. Review of Educational Research, 66, 543–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavin Ivanec, T. (2023). Motivation for the choice of a teaching career: Comparison of different types of prospective teachers in Croatia. Journal of Education for Teaching, 49(3), 355–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulou, M. (2007). Personal teaching efficacy and its sources: Student teachers’ perceptions. Educational Psychology, 27(2), 191–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasch, G. (1960). Probabilistic models for some intelligence and attainment tests. Danish Institute for Educational Research. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, M., Abraham, C., & Bond, R. (2012). Psychological correlates of university students’ academic performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 138(2), 353–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronfeldt, M., Brockman, S. L., & Campbell, S. L. (2018). Does cooperating teachers’ instructional effectiveness improve preservice teachers’ future performance? Educational Researcher, 47, 405–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupp, D., & Becker, E. S. (2021). Situational fluctuations in student teachers’ self-efficacy and its relation to perceived teaching experiences and cooperating teachers’ discourse elements during the teaching practicum. Teaching and Teacher Education, 99, 103252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, U., Doña, B. G., Sud, S., & Schwarzer, R. (2002). Is general self-efficacy a universal construct? Psychometric findings from 25 countries. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 18(3), 242–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schunk, D. H., & DiBenedetto, M. K. (2020). Motivation and social cognitive theory. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 60, 101832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schutz, K. M., Grossman, P., & Shaughnessy, M. (2018). Approximations of practice in teacher education. In P. Grossman (Ed.), Teaching core practices in teacher education (pp. 57–83). Harvard Education Press. [Google Scholar]

- Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2007). Dimensions of teacher self-efficacy and relations with strain factors, perceived collective teacher efficacy, and teacher burnout. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99(3), 611–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strunc, A., & Murray, K. (2019). Understanding the relationship between gender and self-efficacy in northeast Texas public schools. Journal of Human Services: Training, Research, and Practice, 4(1), 1. Available online: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/jhstrp/vol4/iss1/1 (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- Tahmassian, K., & Jalali Moghadam, N. (2011). Relationship between self-efficacy and symptoms of anxiety, depression, worry and social avoidance in a normal sample of students. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, 5(2), 91–98. [Google Scholar]

- Takala, M., Sirkko, R., Räty, K., & Raudasoja, A. (2024). Motives behind Finnish student teachers’ career choices. Education in the North, 31(1), 39–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinto, V. (2017). Reflections on student persistence. Student Success, 8(2), 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschannen-Moran, M., & Hoy, A. W. (2001). Teacher efficacy: Capturing an elusive construct. Teaching and Teacher Education, 17(7), 783–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UCL Erhvervsakademi og Professionhøjskole. (2024, August). Studieordning læreruddannelsen. National del. gældende fra 12024. Available online: https://esdhweb.ucl.dk/D24-2660164.pdf?_gl=1*1v9mbui*_gcl_au*OTQ2NTk0MzU5LjE3MzI0NzAxMzc.*FPAU*OTQ2NTk0MzU5LjE3MzI0NzAxMzc (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- Weisdorf, A. K. (2020). Læreruddannelsen i globalt perspektiv—Et komparativt studie af læreruddannelsen i Danmark, England, Finland, Holland, New Zealand, Norge, Ontario, Singapore, Sverige og Tyskland. Danske Professionshøjskoler. Available online: https://danskeprofessionshøjskoler.dk/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/Laereruddannelsen-i-globalt-perspektiv.-Et-komparativt-studie.pdf (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- Wentzel, K. R., & Miele, D. B. (2009). Handbook of motivation at school. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

| Frequency (%) | |

|---|---|

| Teacher education program | |

| Regular | 383 (94.6) |

| Other b | 21 (5.1) |

| Year of admittance | |

| 2023 | 218 (53.8) |

| 2024 | 187 (46.2) |

| Major teaching subject | |

| Danish | 225 (55.6) |

| Mathematics | 111 (27.4) |

| English | 64 (15.8) |

| Previous completed education | |

| No | 339 (83.7) |

| Yes | 64 (15.8) |

| Previous teaching experience | |

| No | 189 (46.7) |

| Yes | 214 (52.8) |

| Context of teaching experience c | |

| Public school substitute teacher | 167 (41.2) |

| High school | 8 (2.0) |

| Academy Profession Degree Programs (APDs) | 6 (1.5) |

| University college (e.g., teacher, nurse, and the like) | 3 (0.7) |

| University | 3 (0.7) |

| Single (public) lectures | 27 (6.7) |

| Other d | 73 (18.0) |

| Admission track | |

| Grade-based | 160 (39.5) |

| Other qualifications | 242 (59.8) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 252 (62.0) |

| Male | 149 (36.8) |

| Other gender identification e | 3 (0.7) |

| Mean age (SD), range | 23.7 (5.1), 18–66 |

| PSE Subscale (n) | Range | Min | Max | Median (IQR) | Mean | SD | Histogram |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Planning and preparation (396) | 0–21 | 1 | 21 | 14 (11–16) | 13.3 | 3.68 |  |

| Teaching in itself (396) | 0–21 | 5 | 21 | 15 (13–17) | 14.7 | 3.24 |  |

| Differentiation (396) | 0–18 | 5 | 18 | 12 (10–14) | 11.9 | 2.71 |  |

| Class management (396) | 0–15 | 3 | 15 | 10 (9–12) | 10.4 | 2.29 |  |

| Pupils (396) | 0–12 | 3 | 12 | 8 (7–10) | 8.6 | 1.92 |  |

| Adult collaborators (399) | 0–12 | 0 | 12 | 8 (6–9) | 7.6 | 2.63 |  |

| Evaluation and development (396) | 0–18 | 2 | 18 | 12 (10–14) | 12.0 | 3.00 |  |

| Major | df | γ | p Exact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Danish | 60 | 0.26 | 0.0050 |

| Mathematics | 34 | 0.55 | <0.0001 |

| English | 29 | 0.84 | <0.0001 |

| Major Groups Tested | Critical p | p | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|

| Danish and Mathematics | 0.0167 | 0.0667 | Collapsed |

| Danish + Mathematics and English | 0.0250 | 0.0001 | Collapse not possible |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nielsen, T.; Pettersson, M.; Toft, L. Student Teachers’ Practice Self-Efficacy Prior to Their First Field Practice in Schools: Interrelatedness of Subconstructs Within Three Domains of Practice. Psychol. Int. 2025, 7, 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/psycholint7030059

Nielsen T, Pettersson M, Toft L. Student Teachers’ Practice Self-Efficacy Prior to Their First Field Practice in Schools: Interrelatedness of Subconstructs Within Three Domains of Practice. Psychology International. 2025; 7(3):59. https://doi.org/10.3390/psycholint7030059

Chicago/Turabian StyleNielsen, Tine, Morten Pettersson, and Line Toft. 2025. "Student Teachers’ Practice Self-Efficacy Prior to Their First Field Practice in Schools: Interrelatedness of Subconstructs Within Three Domains of Practice" Psychology International 7, no. 3: 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/psycholint7030059

APA StyleNielsen, T., Pettersson, M., & Toft, L. (2025). Student Teachers’ Practice Self-Efficacy Prior to Their First Field Practice in Schools: Interrelatedness of Subconstructs Within Three Domains of Practice. Psychology International, 7(3), 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/psycholint7030059