1. Introduction

As scientific agreement about the growing impacts of climate change increases, knowledge of the psychological foundation of sustainable consumption has grown more critical. The behavior of individuals continues to be a key driver of both environmental deterioration and possible mitigation, and researchers have thus explored the dispositional, affective, and social–cognitive determinants of pro-environmental intentions and behavior (

Vlasceanu et al., 2024). Though conventional models like the Theory of Planned Behavior (

Venkatesh, 2000) and the Value–Belief–Norm Theory have created sound foundations for explaining sustainability-related decisions, there is a growing demand for more integrated models that also entail personality variables along with affective reactions (

Vlasceanu et al., 2024;

Hidalgo-Crespo et al., 2023).

There is already evidence of the predictive potential of personality in sustainability (

Becht et al., 2024) through the ACO model (

Ashton & Lee, 2009). These personality dimensions, which are linked to moral concern, responsibility, and self-regulation, have been shown to be consistently related to pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors (

Ashton & Lee, 2009;

Peng-Li et al., 2021). Meta-analytic results highlight Honesty–Humility as an especially strong predictor of sustainable behavior, accounting for more explanatory power than most Big Five equivalents (

Soutter et al., 2020). Further, research with structural models and mediation analyses established that Honesty–Humility and Openness to Experience shape sustainable behavior not just directly, but also indirectly through moral emotions like guilt and moral anger (

Peng-Li et al., 2021;

Soutter et al., 2020).

Theoretically, Honesty–Humility is an orientation based on fairness, sincerity, and non-exploitation—values that are quite compatible with sustainable consumption values such as equity and regard for future generations (

Peng-Li et al., 2021;

Soutter et al., 2020). High scorers on the trait are less materialistic and more prosocial and ethical in their concerns, and are therefore extremely sensitive to the moral salience of the climate question. Conscientiousness, encompassing self-restraint, future planning, and conscientiousness, can foster sustainable behavior due to its link with personal responsibility and long-term goal orientation—both of which are required when combating global climate change (

Ashton & Lee, 2009;

Peng-Li et al., 2021). Openness to Experience, as expressed in curiosity, intellectual flexibility, and appreciation for beauty, can enhance one’s receptivity to environmental cues and interest in abstract issues such as global warming or environmental systems. These factors also influence emotional sensitivity to climate-related emotions, such as concern and empathy, offering pathways by which personality tendencies can direct action (

Ashton & Lee, 2009;

Peng-Li et al., 2021). Coupling character traits, therefore, offers a theoretically informed approach to the mechanisms by which individual dispositions intersect with affective response in predicting sustainability performance.

Simultaneously, affective predictors like Climate Change Worry (CCW), environmental empathy, and eco-guilt have also been significant motivators of environmental action (

Panno et al., 2021;

Shipley & Van Riper, 2022). Climate emotions are not one-dimensional and, depending on the intensity and context, can even mobilize debilitate action (

Becht et al., 2024). Although there is some evidence to indicate that moderate climate anxiety facilitates pro-environmental behavior (

Qin et al., 2024), other researchers point to the moderating role played by environmental efficacy, future self-continuity, and hope (

Leite et al., 2023). Pride and guilt are among the emotions identified as immediate motivators or mediators between moral awareness and commitment to behavior (

Shipley & Van Riper, 2022).

In spite of such encouraging advances, integrative models that concurrently consider both dispositional and emotional predictors and dispositional traits are uncommon. Furthermore, analytical methods applied to investigate these relations conventionally depended on frequentist approaches that could mask detail in effect sizes, model fitting, and parameter uncertainty. In contrast, Bayesian methods provide a more generally acceptable methodological option in psychological science, enabling more informative inferences through posterior distributions, model averaging, and Bayes factor comparisons (

Bergh et al., 2021). Bayesian regression techniques have been used to test non-linear effects, mediation, and parameter uncertainty in climate psychology research in a more transparent way (

Becht et al., 2024).

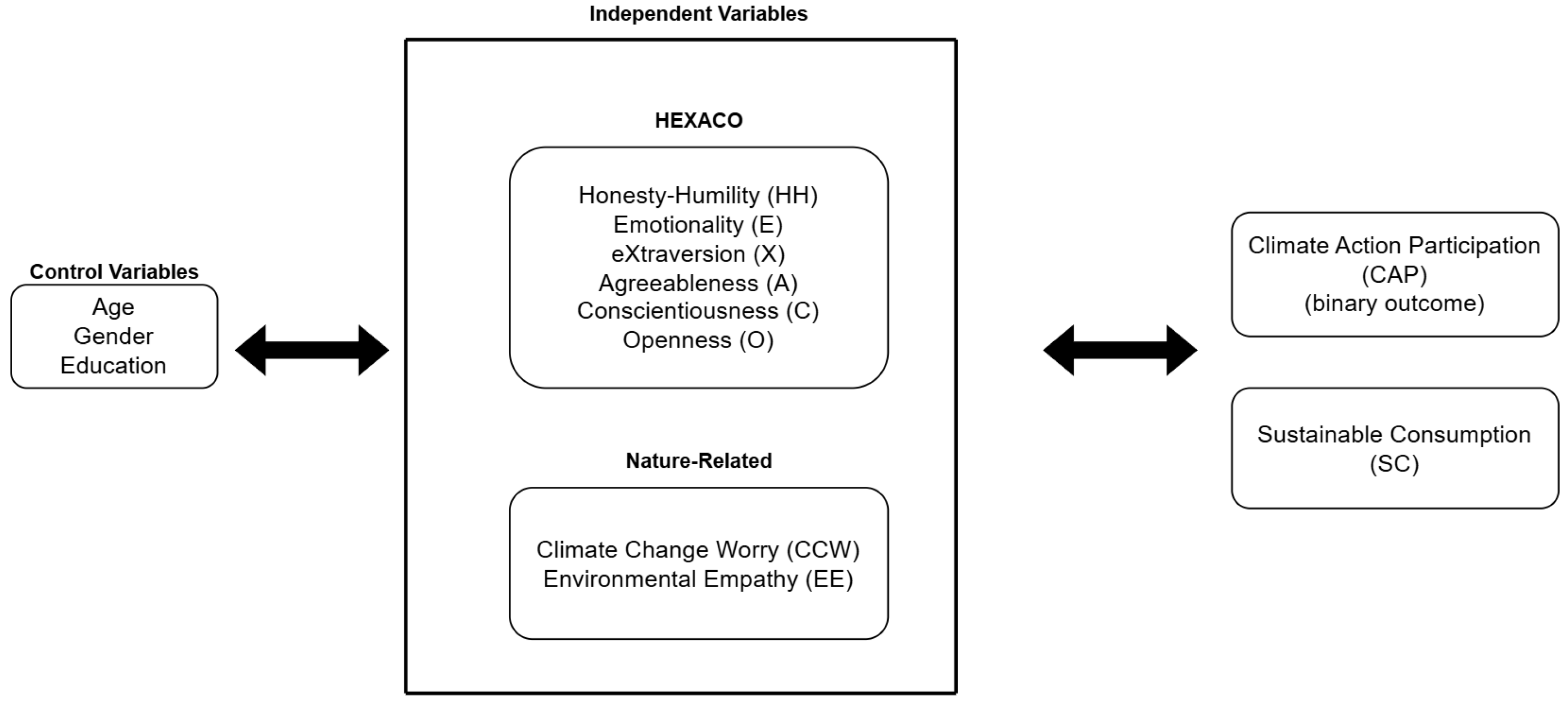

To this end, the current research answers three gaps in the literature: the lack of HEXACO-based trait–emotion models in the research on sustainable behavior, the requirement for methodological progress by Bayesian inference, and the requirement for more behaviorally fine-grained predictors like climate action engagement. Using a sample of the general population comprising 604 participants, we examine how Honesty–Humility, Conscientiousness, climate concern, and affective states predict sustainable consumption behavior and climate action using Bayesian linear and logistic regression analyses performed in JASP. Here in the present study, the term “sustainable consumption” is used to refer particularly to environmentally sound consumer actions—i.e., buying green products, reducing waste, and mindful purchasing. While proximal to the broader construct of “pro-environmental behavior,” which can involve activism as well as conservation behaviors, our particular focus is on consumption-directed decisions made within everyday contexts.

By placing this study at the juncture of personality, emotion, and sustainable behavior, we respond to a pertinent gap in the literature for integrative frameworks that incorporate stable dispositional characteristics and situational emotional reactions. Although past studies have concentrated on investigating personality or emotions related to climate independently, hardly any studies have investigated their joint predictive power for sustainable consumption and climate action involvement. Second, there is hardly any empirical research on the role of climate concern as a potential mediator—i.e., are individuals who score high on Honesty–Humility environmentally virtuous because they are more concerned or because they are guilty about climate change as well? Finally, the use of Bayesian techniques to this field is the exception rather than the norm, especially in country contexts like Greece, and therefore there are still unsolved issues on how these sophisticated methods can help us better understand the psychological processes behind sustainability behavior.

Theoretically, this study contributes to an integrative model, which incorporates moral personality traits and climate-related emotions in the explanation of individual differences in sustainable consumption. This integration combines two convergent strands of environmental psychology research to offer a more intricate explanation of how values and emotions jointly shape people’s behavioral responses to climate change. Methodologically, this study presents Bayesian regression models—through JASP and default priors—as a credible alternative to conventional analyses with the ability to offer a richer interpretation of uncertainty and a more lenient model evaluation. Practically, the results can guide climate education and advocacy in specifying the personality types that are most receptive to emotional appeal and in indicating emotional appeals (e.g., concern, sympathy) that best inspire behavioral change. By integrating trait-based and emotion-based predictors within a firm Bayesian framework, this study contributes to empirical knowledge as well as on-the-ground endeavors to foster sustainable behavior. Practically, the results can direct climate advocacy and education by determining the most emotionally receptive personality profiles to emotional appeals and by targeting the emotional motivators (e.g., anxiety, empathy) that are most effective at inspiring behavioral change. By integrating trait-based and emotion-based predictors within a powerful Bayesian framework, this study contributes to scientific knowledge and on-the-ground action towards sustainable behavior.

The findings of this research highlight the general dominance of education and concern for climate change in driving sustainable consumption, with Bayesian analysis offering strong support for these predictors. Although affective engagement—especially concern for climate change—exerted small but valid effects, all of the personality traits like Honesty–Humility and Conscientiousness had a minimal contribution to the predictive models. Climate action engagement, on the other hand, was not consistently accounted for by any psychosocial or demographic variable. Particularly, gender and education interacted significantly such that the effect of education on sustainable consumption differed significantly by gender, implying crucial sociocultural processes. Collectively, these results illustrate the complex interplay of structural, affective, and demographic variables in sustainability participation.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows:

Section 2 discusses the literature on personality traits, emotional reactions triggered by climate, and their functions in sustainable behavior.

Section 3 describes the conceptual model and methodology, including measurement and sampling details.

Section 3.1 lays out the conceptual model and justification, describing systematically the hypothesized variable interrelations.

Section 4 presents the statistical analysis plan and Bayesian modeling strategy.

Section 5 reports the empirical findings for both sustainable consumption and climate action participation.

Section 6 offers a detailed discussion of theoretical, practical, and methodological implications, while

Section 7 concludes with limitations and directions for future research.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Personality Traits and Sustainable Consumption Behaviors

Current research has increasingly focused on the function of personality traits as antecedents of sustainable consumption behavior and eco-friendly values (

Martin et al., 2022). The traditional dependence on the Big Five model has yielded a beneficial but limited understanding of the psychological foundation of environmental engagement. Individual studies and meta-analyses show that Openness to Experience and Conscientiousness, among others, are positively but modestly correlated with environmentally friendly behaviors like recycling, energy saving, and green consumerism (

Hidalgo-Crespo et al., 2023;

Soutter et al., 2020). Yet, with the addition of Honesty–Humility (H–H) in the HEXACO framework, it has been possible to offer a more moral-based account of ecological concern by including a dimension that involves fairness, honesty, and anti-greed values—qualities of substantial relevance to environmental responsibility (

Kesenheimer & Greitemeyer, 2021;

Soutter et al., 2020).

A number of studies have stated the explanatory ability of H–H and Openness on behavioral and attitudinal results.

Panno et al. (

2021) and

Kesenheimer and Greitemeyer (

2021) showed the way the traits directly and indirectly predict pro-environmental behavior (PEB) via mediators such as pro-environmental attitudes and moral emotions, including moral anger. Particularly noteworthy is the synergistic role played by personality, climate emotions, and social media engagement, as identified by

Balaskas (

2024) in demonstrating how HEXACO facets combine with contextual setting—online posts and emotional framing—to influence behavioral intention. Education level and gender also played moderator roles, with females and more educated individuals being more sensitive to eco-guilt and environmental tagging. This type of evidence is a reflection of the value of bringing personality theories into media and emotional predictors in explaining the multifactoriality of sustainable consumption behavior.

Meta-analytic evidence also offers additional support for the strength of H–H and Openness in large and heterogeneous samples.

Soutter et al. (

2020) and

Cipriani et al. (

2024) found that these dimensions consistently yielded medium effect sizes (r ≈ 0.20–0.25) for attitudes and behaviors, overshadowing Agreeableness and Conscientiousness’s predictive power. In addition, Cipriani’s meta-analysis built on this finding by demonstrating that reduced Openness and a greater endorsement of authoritarian attitudes (e.g., Social Dominance Orientation, Right-Wing Authoritarianism) were both firmly linked to climate change denial. These trends indicate that an ecologically conscious personality is not politically neutral, but instead situated within general sociopolitical and cultural orientations, which can either stimulate or repress its behavior (

Cipriani et al., 2024).

Although some traits like Conscientiousness and Agreeableness have shown weaker yet positive relationships with sustainability behavior, their influence is mediated by factors like environmental norms or feelings of obligation (

Hidalgo-Crespo et al., 2023). Traits such as Neuroticism or Emotionality have more conflicting or varied relationships. For instance,

Sijtsma et al. (

2023) reported zero predictive validity for HEXACO traits for trust behavior in adolescents, with indications that trait effects may be attenuated by developmental stage or context sensitivities. This is a reference to a possible developmental moderation of personality effects and points to the need to control for age, context, and affective states in ecological action modeling.

Recent empirical research has broadened the agenda of sustainable consumption research by incorporating various contexts of behavior, motivational theories, and policy instruments.

Bahja and Hancer (

2021) showed that eco-guilt, even though classically linked to ecologically responsible action, has a direct and strong effect on environmentally responsible tourist behavior (EFTB), but not on repeat intentions—indicating an intricate affect–behavior relationship mediated by context. Conversely,

Zhang et al. (

2025) used a multi-agent model to model the adoption of sustainable behavior within social networks and found that policy incentives like subsidies and information campaigns are more effective in promoting pro-environmental action than green labeling. This systems perspective at the macro level is the opposite finding to that of

Zheng et al. (

2023), at the individual level, where environmental awareness and green self-efficacy were strong predictors of green purchase intentions of green food, while competitive awareness reduced perceived control. These results emphasize the need to segregate motivational paths, as further underscored by

Ye et al. (

2024)’s experimental study of greenwashing: scarcity appeals will not be effective if viewed as manipulative, underscoring the mediating effect of trust and impression management motives.

Horani and Dong (

2023), in studying the sustainable purchasing of phones, also established that perceived sustainable value mediates between customer expectation and behavior intention, moderated by price sensitivity.

In sum, the literature indicates a clear pattern: Honesty–Humility and Openness to Experience are the most consistent and strongest predictors of pro-environmental behavior and climate action intentions, especially when placed within a model that controls for emotional, moral, and contextual effects. This research extends these foundations by using a Bayesian approach to analysis to investigate HEXACO personality traits, climate concern, and emotion-based moderators as predictors of sustainable consumption behavior. In doing so, it seeks to enhance theoretical models of personality-based environmental action and provide applied understanding to inform targeted climate promotion and educational outreach. Moreover, these articles demonstrate a converging focus on affective, cognitive, and contextual influences on green behavior with different assumptions about agency and scope. While

Bahja and Hancer (

2021) and

Zheng et al. (

2023) are most concerned with self-efficacy and network processes,

Ye et al. (

2024) and

Horani and Dong (

2023) focus on perceived credibility and value congruence. Notably, these works extend the scope from personality and determine the appropriateness of affective and situational constructs—drawing on the rationale for the current study to integrate dispositional and emotional determinants under a Bayesian model. Yet the relative lack of theoretical anchorage within trait models in these works serves as a reminder of the absence of the integration of stable personality dispositions and behavioral outcomes—an issue that this research bridges directly.

2.2. The Influence of Worry and Empathy on Sustainable Behavior

Theoretical and empirical developments in the last several years increasingly identify emotional processes—particularly Climate Change Worry (CCW) and ecological empathy—as the key to explaining sustainable behavior and climate action (

Soutar & Wand, 2022). Despite the traditional dominance of cognitive and dispositional approaches to the research agenda, the emerging literature highlights that emotional involvement represents the motivational impetus by which environmental values are translated into behavioral expression (

Zhang et al., 2025;

Zheng et al., 2023).

Climate Change Worry, as a persistent worry or preoccupation with the anticipated impacts of climate change, represents a fundamental psychological construct with observable behavioral implications.

Stewart (

2021) developed the Climate Change Worry Scale (CCWS) to quantify the affective component of this worry, establishing its internal consistency, test–retest reliability, and validity. Empirical findings indicate that moderate levels of CCW typically enable participation in private- and public-sphere pro-environmental behavior (

Vlasceanu et al., 2024;

Becht et al., 2024). For example, Becht et al. found small yet reliable linear associations between CCW and climate action in adolescents in three large-sample studies. These results are the opposite to expectations of increased climate worry necessarily resulting in “eco-paralysis.” Nevertheless, curvilinear effects or reversals contingent on context have been identified within other research, where too much worry sometimes undermines action via perceived helplessness or affective overload (

Qin et al., 2024;

Zheng et al., 2023).

To grasp how climate concern is acted on in sustainable ways, one must take into account the psychological processes involved. Climate Change Concern (CCW) serves as an energizing stimulus when it is moderate and coupled with feeling efficacious or in control. Extended Parallel Process Model and Protection Motivation Theory state that concern is followed by action only if one feels that he or she can make a difference—that is, perceived efficacy goes hand in hand with perceived threat. In its absence, concern is followed by denial, avoidance, or burnout (

Qin et al., 2024;

Zheng et al., 2023). In contrast, environmental empathy is exercised by way of moral concern and affective identification with nature or others who are hurt and can draw upon prosocial norms and guilt-activated moral obligations. CCW and empathy hence both exercise control but in different processes: CCW elicits reflective coping or action in the future when handled positively, but empathy elicits restorative or preventive action by way of emotional identification and value consonance (

Vlasceanu et al., 2024;

Becht et al., 2024). Most importantly, differences between people in terms of self-efficacy, hope, and emotion regulation affect these channels and then condition whether or not feelings become stimuli or burdens for pro-environmental engagement.

Meanwhile, climate anxiety is not homogeneous.

Ágoston et al. (

2022) showed that CCW is diverse and includes related states like eco-anxiety, eco-guilt, and eco-grief with differential behavioral consequences. Qualitative data showed that people who felt eco-grief or eco-guilt participated in compensatory sustainable behavior, that is, these emotions were internalized as moral obligations. Likewise,

Leite et al. (

2023) found that hope and despair mediate the effect of CCW on sustainable behavior: although CCW is a firm predictor of pro-environmental behavior, this connection is strengthened when supplemented by hope stemming from efficacy beliefs and weakened by despair or denial.

These results corroborate wider research hypothesizing environmental empathy—the emotional identification with or moral care for nature and its actualities—which is an auxiliary aptitude to CCW (

Soutar & Wand, 2022). Environmental empathy has been shown to correlate with a higher intention to defend ecosystems, give money to environmental organizations, and endorse climate policies (

Balaskas, 2024). It not only operates as a short-term action trigger but also as a bridge between personality traits (e.g., Honesty–Humility) and behavior, through moral emotions such as eco-guilt and moral outrage (

Panno et al., 2021). People high in empathy might react more to environmental harm and thus be more willing to take restorative or preventative action. Moral anger has especially been demonstrated to predict activism, acting as a kind of collective indignation that stimulates social action (

Hornsey & Pearson, 2024).

Most significantly, research highlights that emotions need to be presented in a positive framework in order to ensure long-term commitment. Though negative moral emotions such as worry and guilt can elicit responses of urgency, over-reliance on distress-based communication can lead to burnout or avoidance. Research by

Ojala et al. (

2021) and

Fischer et al. (

2017) highlights the importance of balancing emotional appeals with the synthesis of moderate worry- and efficacy-based optimism in order to maintain behavior change. For instance, teenagers with greater green self-efficacy and future self-continuity were more prone to translate CCW into significant action (

Qin et al., 2024), corroborating the argument that self-efficacy plays the role of an essential moderator within affective–behavioral models.

Contextual and social cues also influence the behavioral relevance of emotional reactions. Interpersonal encouragement and regular discussion of climate matters were found by

Latkin et al. (

2025) to considerably increase the effect of CCW on activism. In addition, empirical research by

Vlasceanu et al. (

2024) indicates that climate knowledge moderates the behavioral influence of CCW, whereas the personal experience of natural disasters does not. This has implications for communication campaigns in that worry is more likely to lead to action when it is based on correct knowledge and social support.

Cumulatively, these studies weave a consistent narrative: climate emotions, and especially worry, empathy, guilt, and moral anger, are proximal psychological precursors of climate action and sustainable consumption. Situated within a conducive social and cognitive context—such as self-efficacy, environmental concern, and emotion regulation—these emotions activate effective change (

Kesenheimer & Greitemeyer, 2021;

Bahja & Hancer, 2021). But emotional saturation or despair can suppress action, and so it is necessary to examine not only the occurrence of affect, but also its valence, intensity, and regulation.

Extending on this basis, the present research examines how sympathy for the environment and concern about climate change, in interactions with personality and demographic moderators, shape sustainable consumer behavior. Using a Bayesian design, the research also examines whether these affective variables have linear or curvilinear effects and how they interact with individual differences to impact outcomes. In so doing, it adds to the emergent literature that conceives of emotional involvement as an active, multidimensional driver of ecological action.

2.3. Bayesian Methods in Sustainability Research

Bayesian statistical methodologies have progressed significantly in environmental and sustainability science owing to their inferential power, flexibility, and transparency (

Wagenmakers et al., 2018). As compared to frequentist null hypothesis significance testing with

p-values and large-sample approximations, Bayesian inference provides posterior probability distributions and allows for direct assessment of evidence in the form of Bayes factors. Such features have rendered Bayesian methods particularly appealing in fields like environmental psychology, where models tend to include complicated predictor frameworks, modest-to-small sample sizes, and theory-driven hypotheses requiring cumulative proof (

Becht et al., 2024;

Hornsey & Pearson, 2024;

Ojala et al., 2021).

Increasingly, more studies use Bayesian regression to investigate the psychological underpinnings of sustainable behavior. For example,

Becht et al. (

2024) used curvilinear and linear Bayesian models to compare the psychological relationship between climate anxiety and pro-environmental behavior in teenagers. Applying Bayes factors (BFs) to compare models, they found moderate-to-strong support for a simple linear relationship in the majority of analyses (BFs ≈ 7–13), with limited evidence only for a curvilinear “eco-paralysis” effect. This modeling strategy provided a substitute for null hypothesis testing in the form of a formal comparison of theoretical hypotheses and greater interpretive clarity. Bayesian ANOVA and multiple regression were also used by

Von Gal et al. (

2024) to test predictors of climate action intention, wherein posterior inclusion probabilities and BFs were reported for all the variables. In this study, variables such as eco-consequences and eco-anger had inclusion BFs above 4.5, which was interpreted as “moderate-to-strong” evidence in favor of their predictive significance.

Bayesian methods also have been used for multilevel and geospatial models in sustainability science.

Karimi-Malekabadi et al. (

2024) used Bayesian geospatial modeling to examine regional moral values (e.g., fairness, purity) as predictors of environmental attitudes and home carbon emissions in 3000+ U.S. counties. Results indicate that moral values, even after adjusting for political orientation and regional covariates, are still strong predictors of sustainable action at the community level. In addition,

Penker (

2024) used Bayesian negative binomial multilevel models in a cross-national, cross-generational analysis of public-sphere environmental activism and found substantial period effects on environmental protests over time.

Apart from these application-specific uses, Bayesian modeling provides general methodological benefits in sustainability settings. First, it enables the inclusion of prior information—for instance, priors derived from meta-analytic estimates or earlier research—rendering analyses more theory-driven and sensitive (

Bergh et al., 2021). This is especially beneficial for testing multifaceted, integrative models like personality–emotion–behavior chains in sustainability psychology. Second, Bayes factors provide a direct model comparison so that researchers can estimate how much more the data favor one theoretical model over another (e.g., emotion-only vs. personality-plus-emotion models) (

Wagenmakers et al., 2018). Third, Bayesian regression is less affected by small-to-moderate sample sizes compared to frequentist methods and provides full posterior distributions, giving credible intervals that make statements about the true parameter uncertainty without relying on asymptotic assumptions.

For applied research, software packages such as JASP have made Bayesian techniques progressively more user-friendly. JASP supports the specification of user-defined priors, calculation of Bayes factors, and graphical examination of posterior distributions within an open-source environment that encourages transparency and replicability. Research by

Reveco-Quiroz et al. (

2022), demonstrative of this trend, applied Bayesian beta-regression and model-based variable selection to national survey sustainable consumption indexes, highlighting Bayesian modeling’s potential in enhancing prediction and inference in sustainability-oriented measures.

In spite of these advances, the use of Bayesian techniques on mainstream sustainability-related psychology remains relatively limited. There are encouraging applications, yet the literature is still evolving, and more work needs to be undertaken to institutionalize practices for prior selection, model comparison, and Bayes factor interpretation across research. Furthermore, relatively few studies have yet applied Bayesian approaches to mediation, moderation, or interaction modeling in environmental behavior models of this complexity, despite their appropriateness for these analyses. Our research fills this gap by using Bayesian regression modeling to estimate personality trait and climate emotion impacts on sustainable consumption simultaneously, thereby allowing us not only to examine direct relations but also to test the evidence for rival explanatory models. In this manner, we intend to push forward both the methodological and the substantive frontiers of psychological research on sustainability. To address these relationships, the following research questions were formulated:

RQ1: To what extent do HEXACO personality traits (e.g., Honesty–Humility), climate-related emotions (e.g., worry, empathy), and demographic variables predict sustainable consumption behavior in a Bayesian framework?

RQ2: What is the strength of the evidence for specific predictors—such as Honesty–Humility and Climate Change Worry—in explaining sustainable consumption behavior, based on Bayes Factors and posterior estimates?

RQ3: Do personality traits, climate worry, and environmental empathy predict the probability of engaging in climate action (yes/no), and how strong is this evidence under Bayesian logistic regression?

RQ4: Are there meaningful differences in sustainable consumption or emotional responses across gender, age, or education levels, and do these variables interact with psychological predictors?

RQ5: How do demographic factors such as gender and education interact in predicting sustainable consumption, and what is the strength of these interactions based on Bayesian model comparison?

5. Data Analysis and Results

A Bayesian Pearson correlation analysis was conducted to examine the associations among sustainable consumption (SC), HEXACO personality traits, climate-related emotions, and demographic variables. Pearson’s correlation coefficients, 95% credible intervals (CrIs), and Bayes factors (BF

10) were reported to assess the direction, strength, and evidential support for each relationship, as shown in

Table 2.

The relationship between Climate Change Worry (CCW) and sustainable consumption was positive and small (r = 0.09, BF10 = 0.60), with the 95% CrI [0.011, 0.169] containing zero, offering anecdotal support for this association. Honesty–Humility (r = 0.071, BF10 = 0.24) and Conscientiousness (r = 0.029, BF10 = 0.08) also shared similarly small correlations with SC, and Bayes factors did not yield enough evidence to include them. Emotionality (r = 0.020, BF10 = 0.06) and Extraversion (r = −0.021, BF10 = 0.06) were not consistently related to SC.

There was no strong evidence for an association between SC and environmental empathy (r = −0.078, BF10 = 0.32) or with the demographic variable gender (r = −0.104, BF10 = 1.35). The 95% CrIs for all these correlations contained zero, and the Bayes factors were not greater than the threshold for moderate evidence (i.e., BF10 > 3).

The most robust evidential support in the data was observed between Openness and Emotionality (r = −0.216, BF10 = 85.618) and Openness and Honesty–Humility (r = 0.150, BF10 = 45.84), neither of which had 95% CrIs containing zero. Both correlations did not involve the dependent variables but informed us about the latent trait structure and possible collinearity for regression modeling.

In total, the Bayesian correlation analysis was unable to discover any substantial correlations between sustainable consumption and any predictor with BF10 ≥ 3. Nevertheless, the results are useful initial pointers for variable inclusion in later regression analyses.

5.1. Bayesian Multiple Linear Regression on Sustainable Consumption

In order to compare demographic and psychological predictors of sustainable consumption, a Bayesian model comparison method was used in JASP. Personality (Honesty–Humility, Conscientiousness, Emotionality, Extraversion, Agreeableness, Openness), climate emotions (Climate Change Worry [CCW], environmental empathy [EE]), and demographic (gender, age, education) variables were added as possible predictors. Bayesian linear regression models were estimated with the Jeffreys–Zellner–Siow (JZS) prior (r = 0.354), and model probabilities were assessed via Bayes adaptive sampling (BAS), comparing against the null model (education alone).

Table 3 shows the ten highest fitting models based on Bayes factors (BF

10) and posterior model probabilities. The most well-supported model was the one with education as the sole predictor of SC, with moderate evidence for the alternative compared to the null (BF

10 = 1.00) and posterior model probability of P(M|data) = 0.137. The inclusion of gender provided a modest increase in explanatory power (R

2 = 0.043), yet only anecdotal evidence for the leading model (BF

10 = 1.789).

The inclusion of Climate Change Worry (CCW) alongside gender and education yielded a model with moderate evidence (BF10 = 4.599) and higher explained variance (R2 = 0.052), suggesting CCW contributes incrementally to the prediction of sustainable consumption. Models including broader HEXACO traits (e.g., Honesty–Humility, Conscientiousness, Openness) were worse than more parsimonious models, with substantially lower posterior probabilities and Bayes factors (e.g., BF10 = 0.009 for the full model).

Generally, the data support a modest role for climate change concern and education in predicting sustainable consumption behavior. Somewhat unexpectedly, the model incorporating CCW, sex, and education had more than four times more support than the null model did, indicating that emotional concern regarding climate change, independent of demographics, is perhaps a valuable predictor of pro-environmental consumption.

Posterior estimates for the regression coefficients give additional information on the most probable predictors of sustainable consumption behavior (

Table 4). As can be gleaned from

Table 2, education was the most robust and stable predictor with an inclusion Bayes factor (BF

inclusion) of 785.19, indicating conclusive evidence for its impact. The posterior mean for the education coefficient was 0.103 with a 95% credible interval that did not include zero [0.057, 0.149], indicating that greater educational attainment was credibly related to lower sustainable consumption scores.

Climate Change Worry (CCW) also showed moderate evidence for inclusion (BFinclusion = 1.28), with a posterior mean of 0.056 and a credible interval narrowly excluding zero [0.000, 0.166]. This indicates that participants who are more worried about climate change are somewhat more likely to consume sustainably, although the evidence strength is still limited. Gender also had anecdotal support for inclusion (BFinclusion = 1.434), a negative posterior mean (−0.065), and a credible interval just below zero [−0.181, 0.000], suggesting that males are less sustainable in their consumption than females, although this result is not reliable. The other predictors, Honesty–Humility, environmental empathy, and Openness, all had BFinclusion statistic values between 0.5 and 0.6, indicating no strong evidence either way for including them. Credible intervals for the coefficients either included zero or had lower bounds close to zero, nullifying any case for credible effects. The remaining personality dimensions (Conscientiousness, Emotionality, Extraversion, Agreeableness) and age all had BFinclusion values < 0.5 and broad credible intervals spanning zero, indicating evidence against their importance in this model.

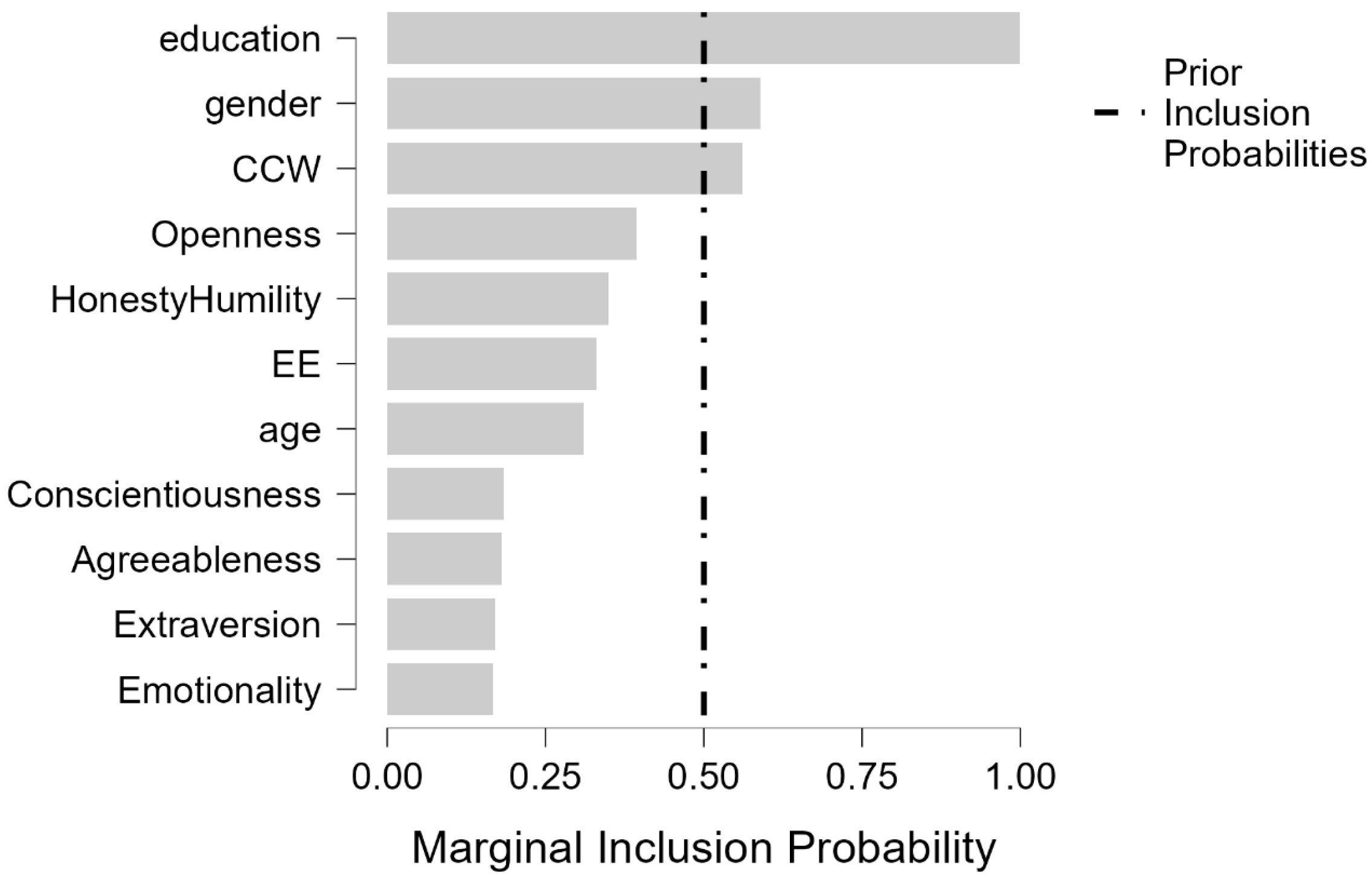

Figure 2 plots marginal posterior inclusion probabilities for each of the predictors in the Bayesian linear regression model of sustainable consumption. The dashed vertical line indicates the prior inclusion probability of 0.50 under a uniform model prior (i.e., all predictors had equal a priori chances of being included). Bars extending to the right of this line suggest greater empirical support for inclusion based on the observed data.

Of all the predictors, education had the highest posterior inclusion probability—far exceeding the prior—showing definitive evidence of being in the model. It was followed closely by gender and climate change concern (CCW), which both recorded posterior inclusion probabilities greater than 0.50, offering moderate to strong evidence of their predictive utility.

Conversely, all three variables Emotionality, Extraversion, and Agreeableness also had inclusion probabilities far lower than the prior threshold, indicating that there was negligible or no evidence within the data that would include these predictors in the model. Conscientiousness, age, and environmental empathy (EE) also failed to pass the prior inclusion threshold regardless of theory relevance.

In total, this inclusion probability profile acknowledges the contribution of demographics (gender, education) and climate-related affective engagement (CCW) in describing sustainable consumption and disputes the role of numerous aspects of personality after considering model uncertainty.

5.2. Bayesian Logistic Regression on Climate Action Participation

We performed a Bayesian logistic regression to determine demographic and psychological predictors of climate action participation. Models were compared based on Bayes factors (BF10), posterior model probabilities, and variance explained (R2).

The null model with no predictors received the highest posterior model probability (P(M|data) = 0.408) and was used as the reference model (BF

10 = 1.00). The full model with all the demographic and psychological predictors received little support (BF

10 = 0.057, P(M|data) = 0.023, R

2 = 0.004), demonstrating that the data favored the null model over any single predictor or combination (

Table 5).

Of the individual predictor models, models featuring Agreeableness (BF10 = 0.458), Extraversion (BF10 = 0.430), and Climate Change Worry (CCW) (BF10 = 0.397) had the highest relative model evidence. These all fell short of BF10 > 1, though, offering anecdotal-to-weak evidence against their value as predictors.

No model achieved moderate levels of evidence (BF10 > 3) compared to the null. The results therefore indicate that, given current data and priors, there is no strong evidence that any individual psychological or demographic variable significantly adds to the prediction of climate action engagement over and above the null model.

Posterior summaries indicated that there was no predictor with strong evidence for inclusion, as all Bayes factors for inclusion (BF_incl) were less than the standard cut-off of 3, and all 95% credible intervals (CrIs) contained zero (

Table 6). Agreeableness, for example, had the highest probability of inclusion (P(incl|data) = 0.240), yet the Bayes Factor for inclusion was modest (BF_incl = 0.316), and the posterior 95% CrI [−0.063, 0.115] contained zero, suggesting no credible effect. Climate Change Worry (CCW) had a posterior mean of 0.008 and a CrI of [−0.074, 0.129], again showing no significant contribution. The other predictors (e.g., Honesty–Humility, Emotionality, EE, gender, education, age) all had posterior inclusion probabilities near or below 0.22, and the accompanying CrIs included zero, offering anecdotal-to-weak support for inclusion.

These findings indicate that none of the variables in question singled out in this model situation offer strong evidence of a significant predictive relationship with involvement in awareness actions related to the climate.

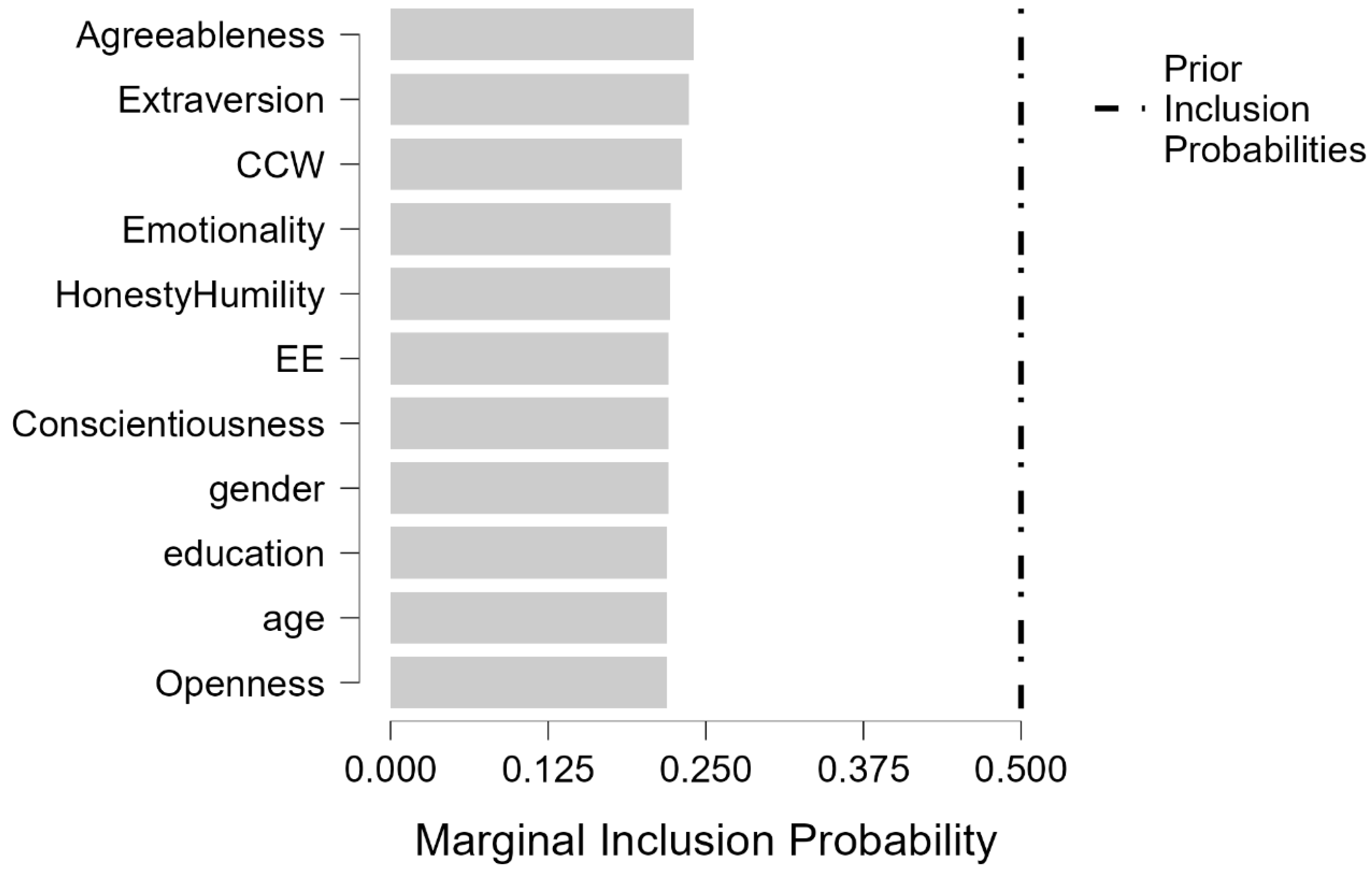

As can be seen from

Figure 3, all of the predictors featured posterior inclusion probabilities less than the prior threshold value of 0.50, which meant the data were not sufficient in their support to include them in the logistic regression model of climate action participation. The education, sex, and personality dimensions of Honesty–Humility and Climate Change Worry had moderate inclusion probabilities (~0.22–0.24), which were still far from the values typically accepted to indicate strong effects (i.e., >0.75). This graphical support supplements the numerical model comparisons, together favoring the null model and the lack of strong individual predictors in this instance.

5.3. Group Comparisons and Differences

5.3.1. Gender Differences

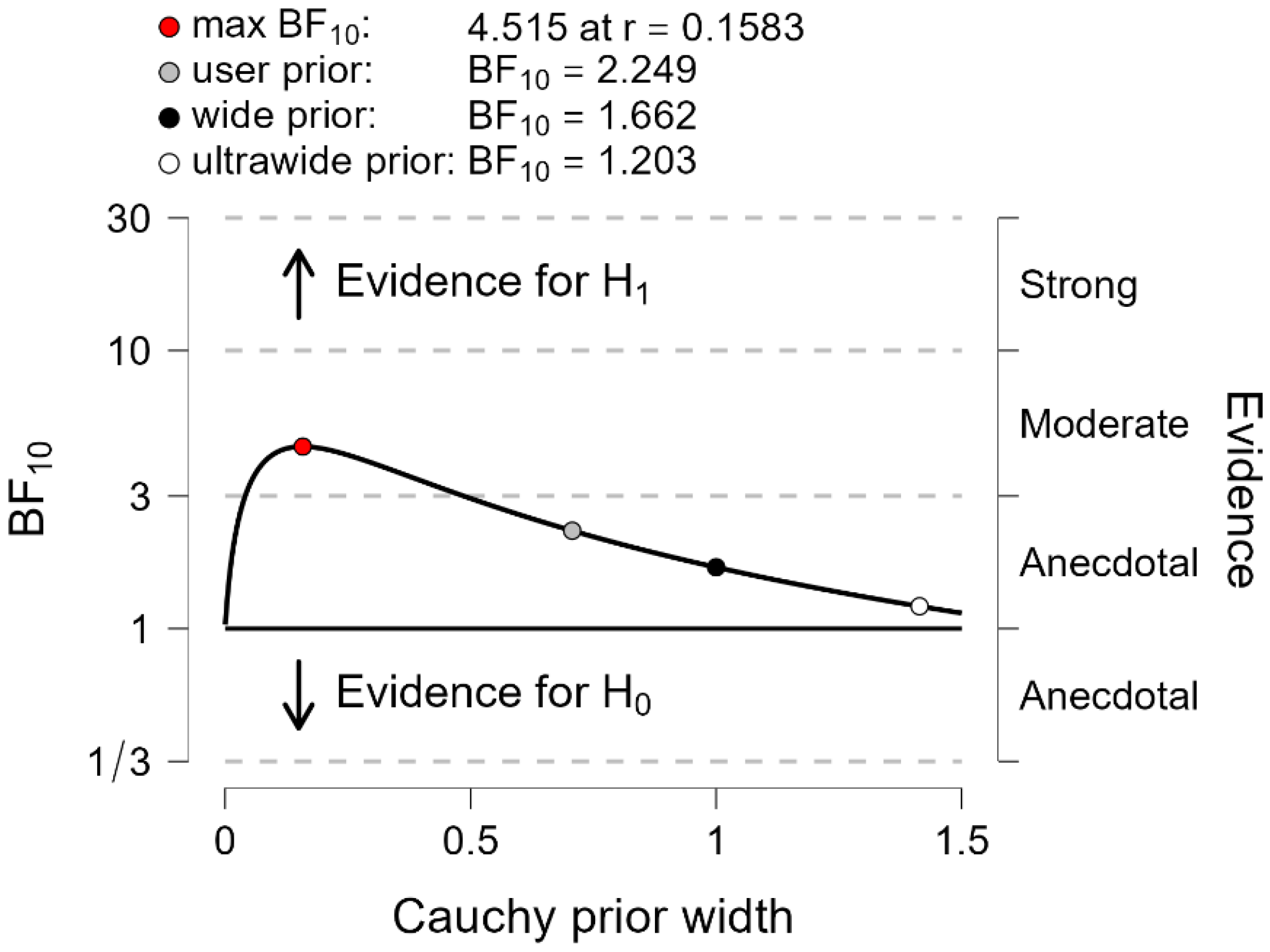

Bayesian independent samples

t-tests were used to examine gender differences in sustainable consumption (SC), Climate Change Worry (CCW), and environmental empathy (EE). For SC, the Bayes factor (BF

10 = 2.25) offered anecdotal-to-moderate evidence for a gender difference. For CCW (BF

10 = 0.30) and EE (BF

10 = 0.33), the evidence was against the alternative hypothesis, indicating there was no credible difference between groups for these variables (

Table 7).

Bayesian inference provides moderate evidence for gender association with SC behavior differences. The strongest evidence for the alternative hypothesis (H₁: gender differences in SC) is at a prior width of 0.1583 and a maximum BF10 = 4.515. With the default user prior (r = 0.707), the BF10 = 2.249, providing moderate evidence for gender differences. Wider priors decrease the level of evidence to the anecdotal range. This finding is resilient to past assumptions to a moderate degree, though it is attenuated with broader priors. The result encourages the ongoing investigation of gender as a legitimate demographic moderator in models of sustainable behavior.

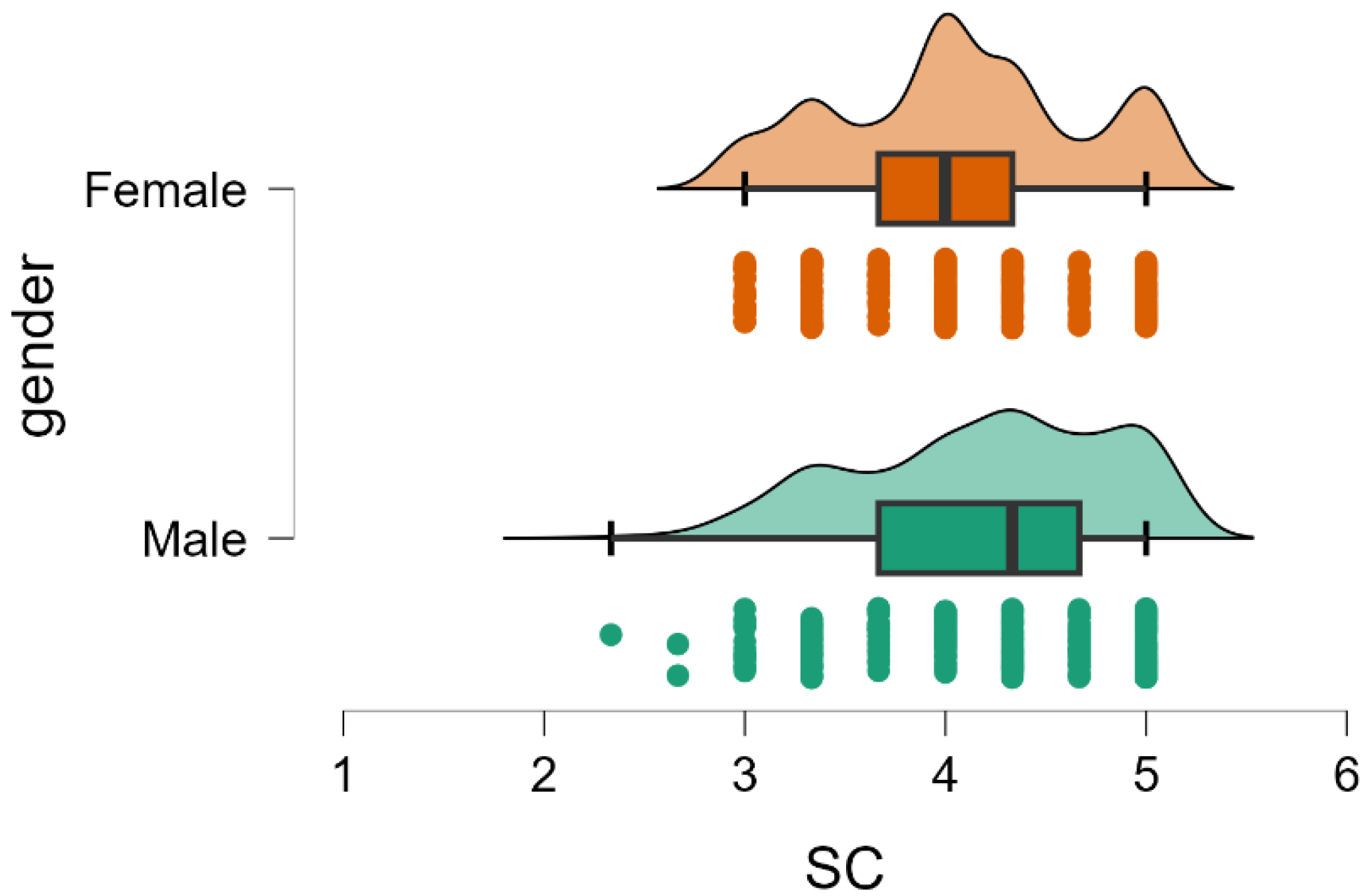

Visual inspection is consistent with the Bayesian analysis, which identifies a small but persistent trend for women to have more sustainable consumption scores (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5). There is still a considerable overlap of distributions, highlighting that gender differences, although present, are not pronounced.

5.3.2. The Effect of Education on Sustainable Consumption

In order to check if sustainable consumption (SC) varied across education levels, a Bayesian ANOVA was performed. The predictor model including education was very strongly preferred over the null model, BF

10 = 52.77, suggesting very strong evidence in favor of an effect of education on SC. The posterior model probability was P(M|data) = 0.981, whereas for the null it was P(M|data) = 0.019. The Bayes factor for inclusion (BFinclusion) for education was 52.77, which meant that the inclusion of education in the model was far more probable than exclusion. The model-averaged explained variance was limited, with an R

2 = 0.033, and 95% CI [0.008, 0.063]. The findings indicate that educational level is an appropriate predictor of sustainable consumption behavior among the sample, although the amount of explained variance is still small (

Table 8).

To investigate more closely the significant main effect of education on sustainable consumption (SC) which was discovered, Bayesian post hoc tests were conducted.

Table 9 provides an overview of the pairwise comparisons with default Cauchy priors and multiple-testing-corrected posterior odds.

The results provided extremely strong evidence for differences between the Doctoral and a number of lower education levels. More specifically, the High School and Doctoral comparison returned a Bayes factor (BF10) of 67.42, and Bachelor’s and Doctoral returned BF10 = 11.22, both providing conclusive support for a group difference. Moderate evidence was also found for Master’s and Doctoral (BF10 = 5.36), and High School and PhD Candidate (BF10 = 7.45). On the other hand, other comparisons (e.g., High School vs. Bachelor’s, PhD Candidate vs. Doctoral) resulted in anecdotal or no data, with BF10 < 3.

These results affirm that education at higher levels, i.e., Doctoral-level, is linked to more sustainable consumption, validating the hypothesis that education is a significant predictor of pro-environmental behaviors.

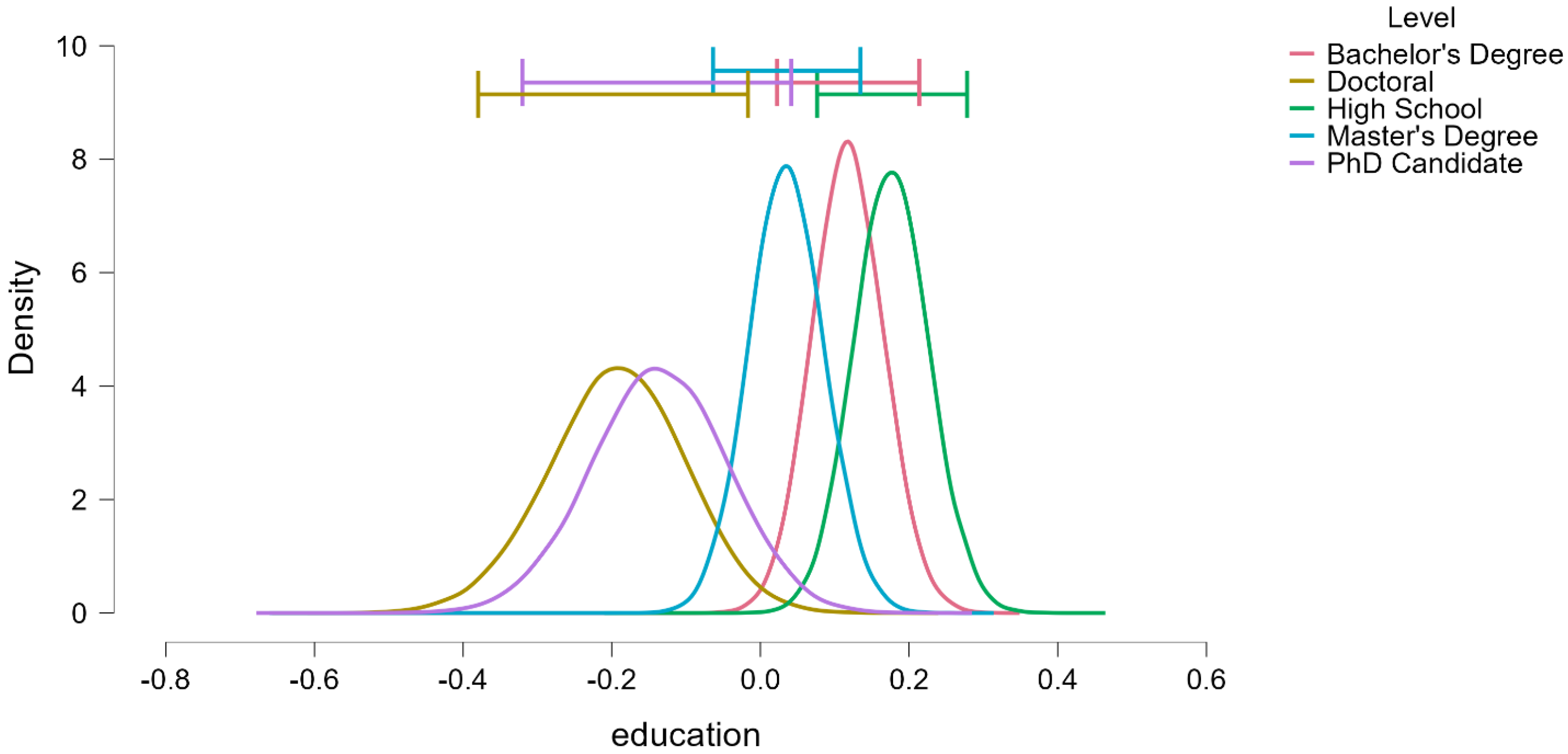

Figure 6 presents the posterior distributions of sustainable consumption (SC) across education levels. As is apparent from the plot, Doctoral degree holders have higher SC than High School graduates with non-overlapping 95% credible intervals for the presence of such a difference. These depicted differences are in line with the results of the Bayesian ANOVA and post hoc tests of extreme evidence for differences between Doctoral and lower levels of education (e.g., BF

10 = 67.42 for Doctoral vs. High School). The plot gives a graphical overview of the distribution of model-estimated group effects, confirming the finding that higher education level is linked to more sustainable consumption behavior.

5.3.3. Age Group Differences in Sustainable Consumption

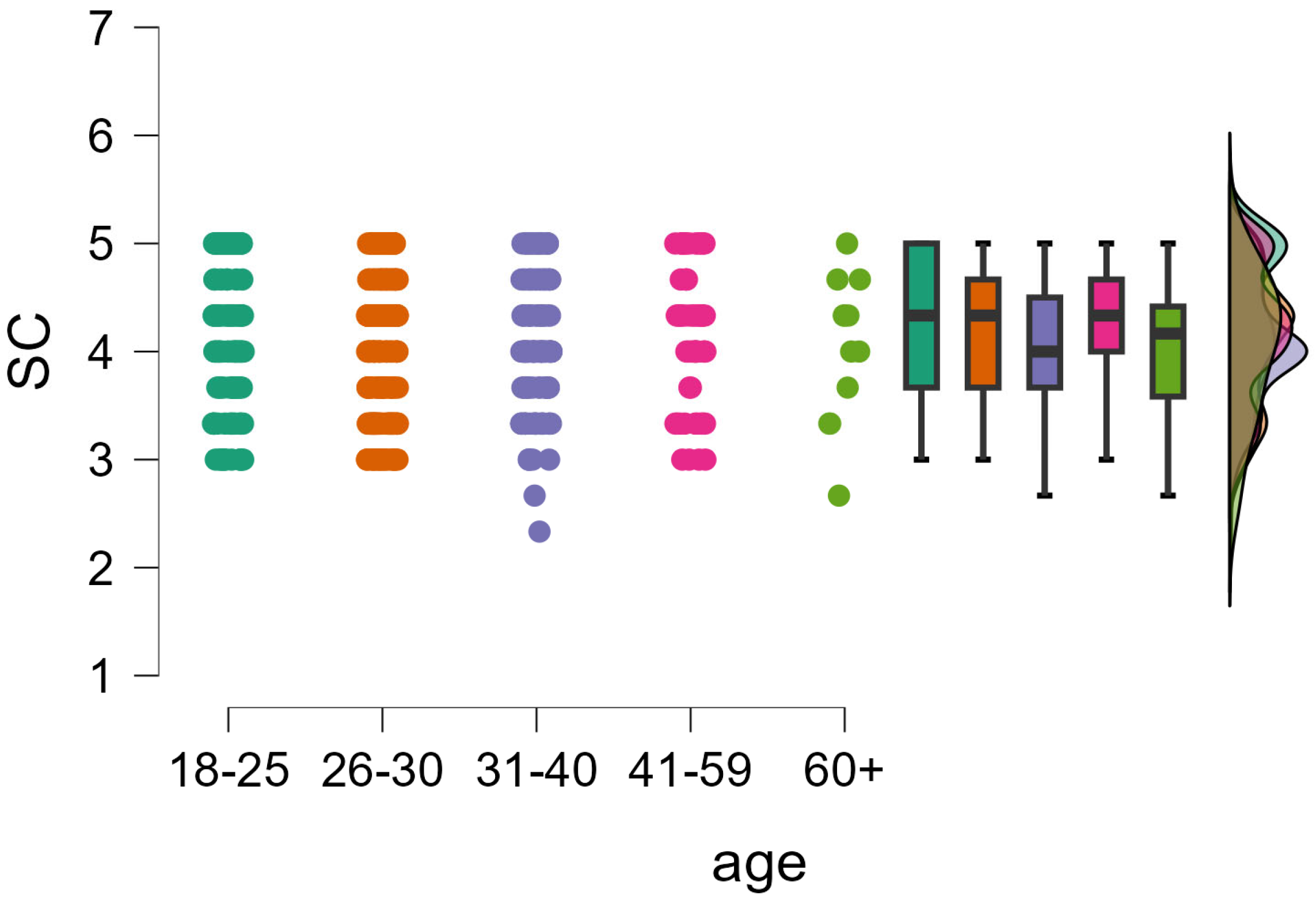

We conducted a Bayesian ANOVA to determine if sustainable consumption (SC) varied as a function of age group (

Table 10). Model comparison revealed that the null model was very much favored over the age model, BF

10 = 0.146, with moderate evidence for the null hypothesis that SC does not vary by age. The posterior probability for the null model was P(M|data) = 0.873, whereas P(M|data) = 0.127 was the posterior probability for the age model.

Effect analysis also favored the marginal contribution of age with a Bayes factor for inclusion, BFinclusion = 0.146, and a posterior inclusion probability of merely 0.127. Model-averaged R2 was 0.002 with a 95% credible interval of [0.000, 0.023], reflecting exceedingly trivial explained variance in SC based on age.

These findings offer moderate confirmation of the lack of age-based differences in sustainable consumption within the sample.

Post hoc Bayesian pairwise comparisons by age group revealed no significant pairwise differences in sustainable consumption (

Table 11). The most compelling contrast was between the age range 18–25 and 31–40 (BF

10 = 2.069), which provided anecdotal-to-moderate evidence for a difference in SC in the younger adults’ favor. All other pairwise comparisons resulted in Bayes factors less than 1, in favor of the null hypothesis. The implications are that age differences in sustainable consumption in this sample are perhaps small or variable.

These results suggest that while SC appears visually differentiated in some age categories (see

Figure 7), the Bayesian evidence does not strongly support a systematic effect of age on sustainable consumption behavior.

5.4. Interaction Between Gender and Education on Sustainable Consumption

In order to test the interaction effect of gender and education on sustainable consumption (SC), a Bayesian ANCOVA with emotional engagement (EE), Climate Change Worry (CCW), and HEXACO personality traits as covariates was performed (

Table 12). Model comparison indicated that the model with the interaction term (gender × education) and CCW had the highest posterior model probability, P(M|data) = 0.411, and outperformed all the other models with a Bayes factor of BF

10 = 1.000. The model performed better than the null model (with the covariates only) and competing models without the interaction term.

In the analysis of effects, the gender by education interaction was strongly supported with a posterior inclusion probability of P(incl|data) = 1.000 and a Bayes factor for inclusion of BF_incl = 25,641.56, which shows strong evidence for including the interaction (

Table 13). CCW also provided moderate evidence for inclusion (BF_incl = 2.14), but EE did not have substantial support (BF_incl = 0.66). Model-averaged predictions indicated a mean R

2 = 0.123 (95% CI [0.076, 0.176]), indicating that the predictors and interactions included in the models accounted for around 12.3% of SC variance.

In order to more closely explain the two-way interaction influence of gender and education level on sustainable consumption (SC), Bayesian post hoc tests were carried out with independent samples

t-tests with default Cauchy priors (r = 1/√2). The comparisons showed particular group differences, and Bayes factors (BF

10) were included to provide evidence strength for every comparison (

Table 14).

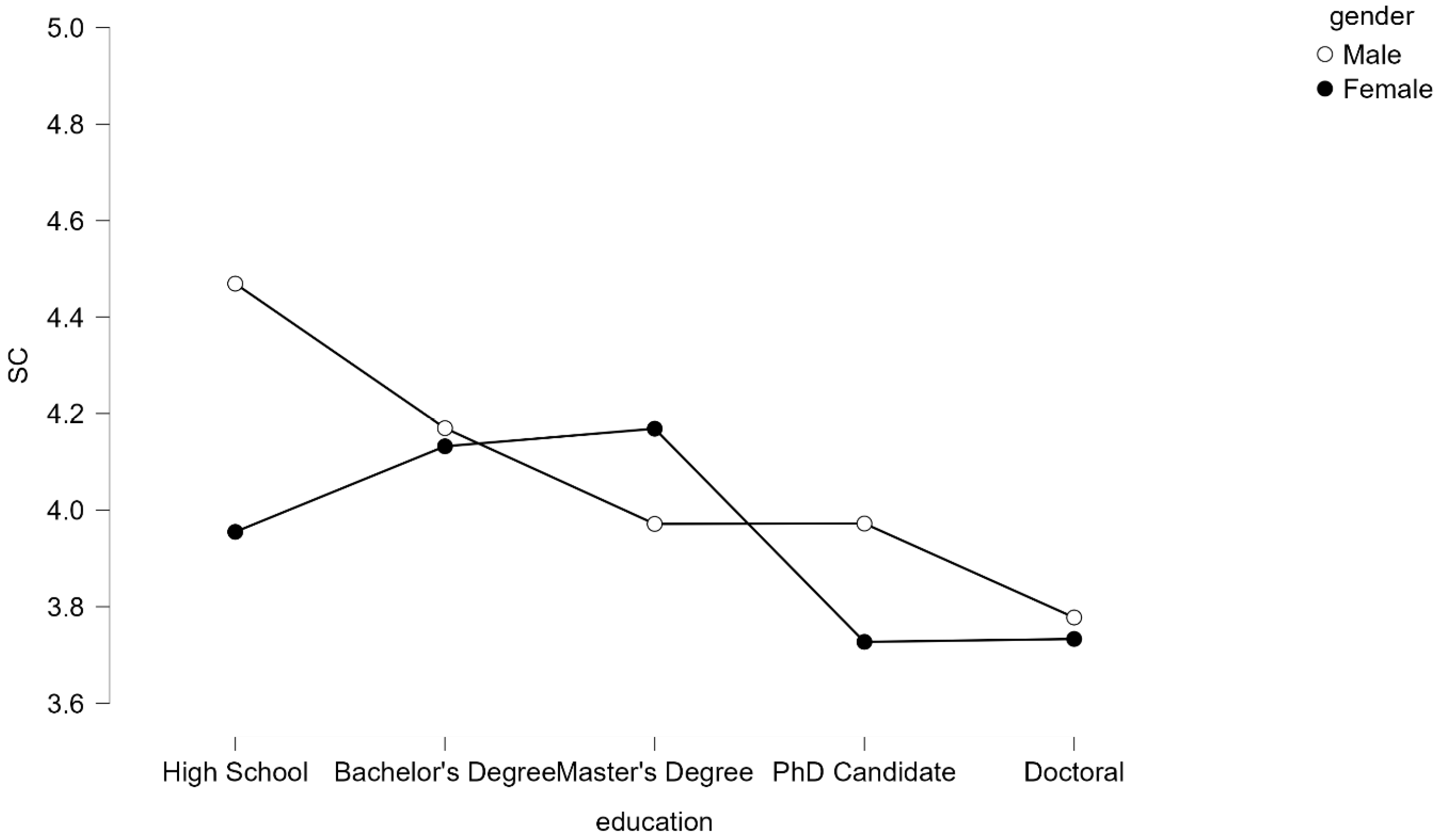

The comparison between males and females provided modest support for a difference, where the males had higher scores for SC compared to the females (BF10 = 2.249, error = 0.009). Post hoc tests for level of education revealed a number of strong-to-overwhelming effects. More specifically, SC was rated significantly higher by the Doctoral-level group compared to the High School-educated group (BF10 = 67.421), and also compared to the Bachelor’s- and Master’s-level groups (BF10 = 11.215, BF10 = 3.562, respectively). Moderate-to-strong evidence was also found in support of higher SC in PhD Candidates versus individuals with just a High School degree (BF10 = 7.454), and in individuals with a Master’s degree versus individuals with a High School degree (BF10 = 3.457). Comparatively, contrasts between lower or neighboring levels of education provided anecdotal to poor evidence, i.e., High School and Bachelor’s degree (BF10 = 0.400), Bachelor’s and Master’s degree (BF10 = 0.212), Bachelor’s and PhD Candidate (BF10 = 1.843), Master’s and PhD Candidate (BF10 = 1.020), and PhD Candidate and Doctoral (BF10 = 0.320). These findings suggest that SC behavior tends to increase notably at the highest levels of formal education

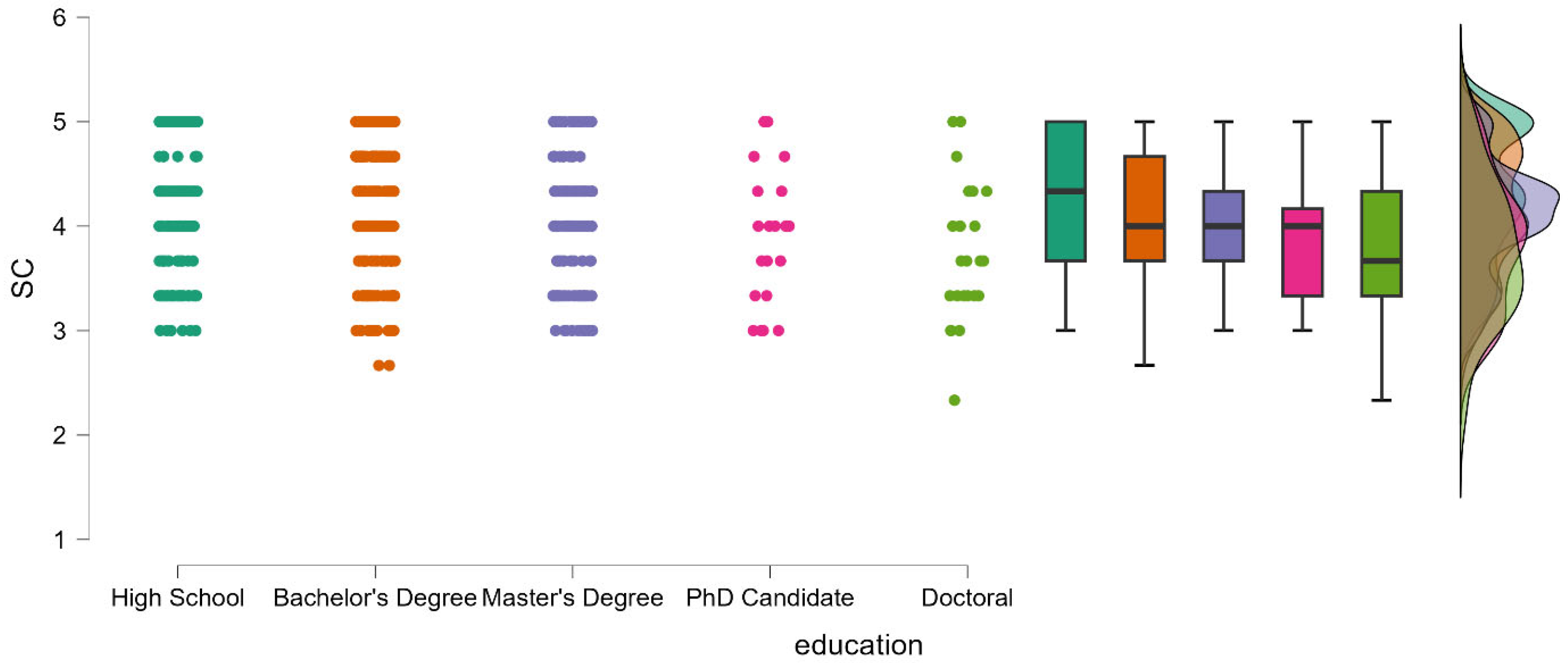

To supplement the statistical results and offer interpretability, the following are the plots of distributional trends and the interaction effects of the Bayesian analyses (

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10). The plots give a clearer sense of how sustainable consumption (SC) differs by education levels and gender and how their interaction influences such differences. Visual inspection supports the main effects specified in the model, pointing out both the main effects and the subtle interaction between the categorical predictors.

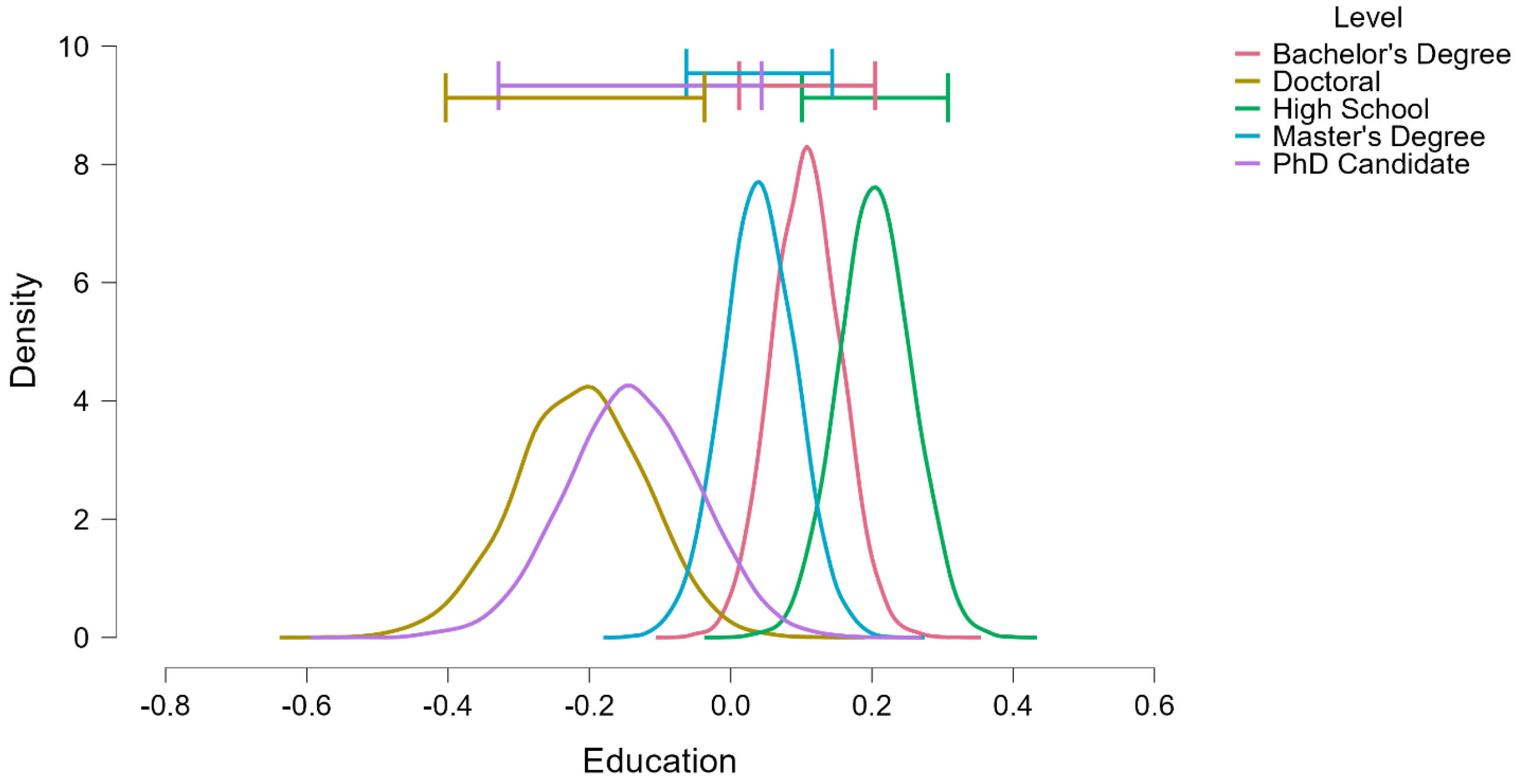

Figure 8 illustrates the distribution of SC scores across education groups. The raincloud plot shows that individuals with Doctoral and PhD Candidate education tend to report higher SC compared to High School and Bachelor’s degree groups, in line with the Bayesian ANCOVA results indicating strong-to-extreme evidence for group differences (e.g., BF

10 = 67.421 for Doctoral vs. High School). The distribution shapes and median shifts highlight heterogeneity in sustainable consumption across education levels.

Figure 9 depicts the posterior distributions for each education level’s effect on SC. The density peaks for Doctoral and PhD Candidate groups are shifted leftward (lower log effect sizes), while High School and Master’s degree are more right-skewed, reflecting the observed post hoc comparisons. The largest divergence is observed between Doctoral and High School groups, consistent with the extreme evidence (BF

10 = 67.421), supporting education as a significant predictor of SC.

Figure 10 is an interaction plot of the effect of education by gender on SC scores. The patterns indicate a gender–education interaction in which women have a little more SC at the mid-level education (Master’s), and men have a sharper drop from High School to Doctoral. This pattern is in support of the inclusion of the gender × education interaction term in the Bayesian ANCOVA, in which the interaction term had overwhelming evidence (BF_incl = 25,641.556). This interaction partly explains the subtle variations in how level of education impacts sustainable consumption differently in each gender.

These findings support that the Doctoral-level-educated participants demonstrated consistently higher sustainable consumption behavior, validating the theory that higher education is associated with stronger pro-environmental behavior.

7. Conclusions

Combating climate change demands more than awareness—it demands specific interventions that elicit commitment to action. This research demonstrates that sustainable consumption is most strongly explained by structural and affective factors, i.e., education and worry about climate change, and personality traits, such as Honesty–Humility, have restricted explanatory potential. The robust gender by education interaction also highlights the requirement for shaping interventions around sociocultural identities. Our results validate integrative sustainability behavior models that emphasize education experience and affective commitment beyond trait prediction. Although climate concern moderately inspires sustainable behavior, climate action engagement seems to be governed by wider social and contextual processes, beyond individual dispositions or emotions. Methodologically, Bayesian analysis promotes transparency and accuracy in assessing predictor importance, particularly in small-effect and theoretically intricate models.

For all its strengths, this study is not without limitations. First, the cross-sectional design circumscribes causal inference and insight into dynamic behavioral change. Longitudinal and experimental designs would be an asset for subsequent research to determine the temporal order and examine intervention effects over time (

Taherdoost, 2016). Second, the use of self-report measures runs the risk of biases like social desirability or recall error (

Vehovar et al., 2016). While validated measures and pilot testing were used to provide maximum measurement reliability, objective behavioral data like ecological momentary assessments or observational measures would contribute to validity. Third, the reliance on snowball sampling limits the generalizability of the results. The method, nonetheless, allowed access to a diverse sample that would be hard to obtain using probability-based methods (

Olsen & St George, 2004;

Sandelowski, 2000).

Follow-up studies need to investigate indirect processes, for instance, the mediating role of moral emotions or cognitive appraisals, and contextual moderators such as media exposure, subjective norms, or political affiliation (

Ojala et al., 2021). Null results for climate action participation (CAP) also deserve more scrutiny—especially in designs controlling for situational constraints, structural barriers, and motivational thresholds that vary between attitudinal and activist behavior. Methodologically, subsequent research should continue to apply Bayesian models to multilevel, dynamic, or person-centered models that will better capture trait–emotion–context interactions (

Parmentier et al., 2024;

Karimi-Malekabadi et al., 2024). The extension of the research to multicultural settings and social processes would thus add to the generalizability of the findings based on sensitivity to the reality that while environmental issues occur worldwide, their experiences are not necessarily uniform across environments and societies. While composite scores served to capture these complex constructs, it is believed that subscale analyses would provide fuller appreciations of their different dimensions. Fourth, while the study sampled adults across the full range of ages, the 40-plus age group was to some extent underrepresented. This restricts the generality of age-related findings, and future research should try stratified or quota sampling with the aim of achieving an improved balance between the age groups. Additionally, future studies would be advantaged by measuring climate-related content knowledge, since it can moderate or mediate the influence of dispositional traits and emotions on pro-environmental behavior. Understanding how knowledge interacts with personality and affective involvement could explain the behavioral heterogeneity among various populations.

In total, this research adds to sustainability psychology by virtue of the integration of dispositional and emotional predictors within a Bayesian model. The findings show the priority of education and climate concern in predicting sustainable consumption and contradict the presumed supremacy of stable personality traits as drivers of climate action.

Finally, this research confirms the value of developing emotionally intelligent, well-educated, and socially mobilized citizens as agents of environmental transformation. A grasp of the psychological and demographic contours of engagement with sustainability is crucial to shaping interventions that will echo across varied populations. To anchor this understanding, the current research provides both a methodological and theoretical underpinning for future work on activating personal involvement with collective climate responsibility—a foundation for a more engaged, participatory, and resilient society.