Predictors of Street Harassment Attitudes in British and Italian Men: Empathy and Social Dominance

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Street Harassment: Definition, Prevalence, and Consequences

1.2. Street Harassment: Literature and Limitations

1.3. Cognitive Empathy, Social Dominance Orientation, and Population Differences

1.4. Current Study

- (a)

- Lower cognitive empathy for harassed women predicts higher street harassment tolerance.

- (b)

- Higher SDO predicts higher street harassment tolerance.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Online Questionnaire

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Analysis Plan and Statistical Power

3. Results

3.1. Impact of Video on Street Harassment Tolerance

3.2. Psychological Predictors of Street Harassment Tolerance

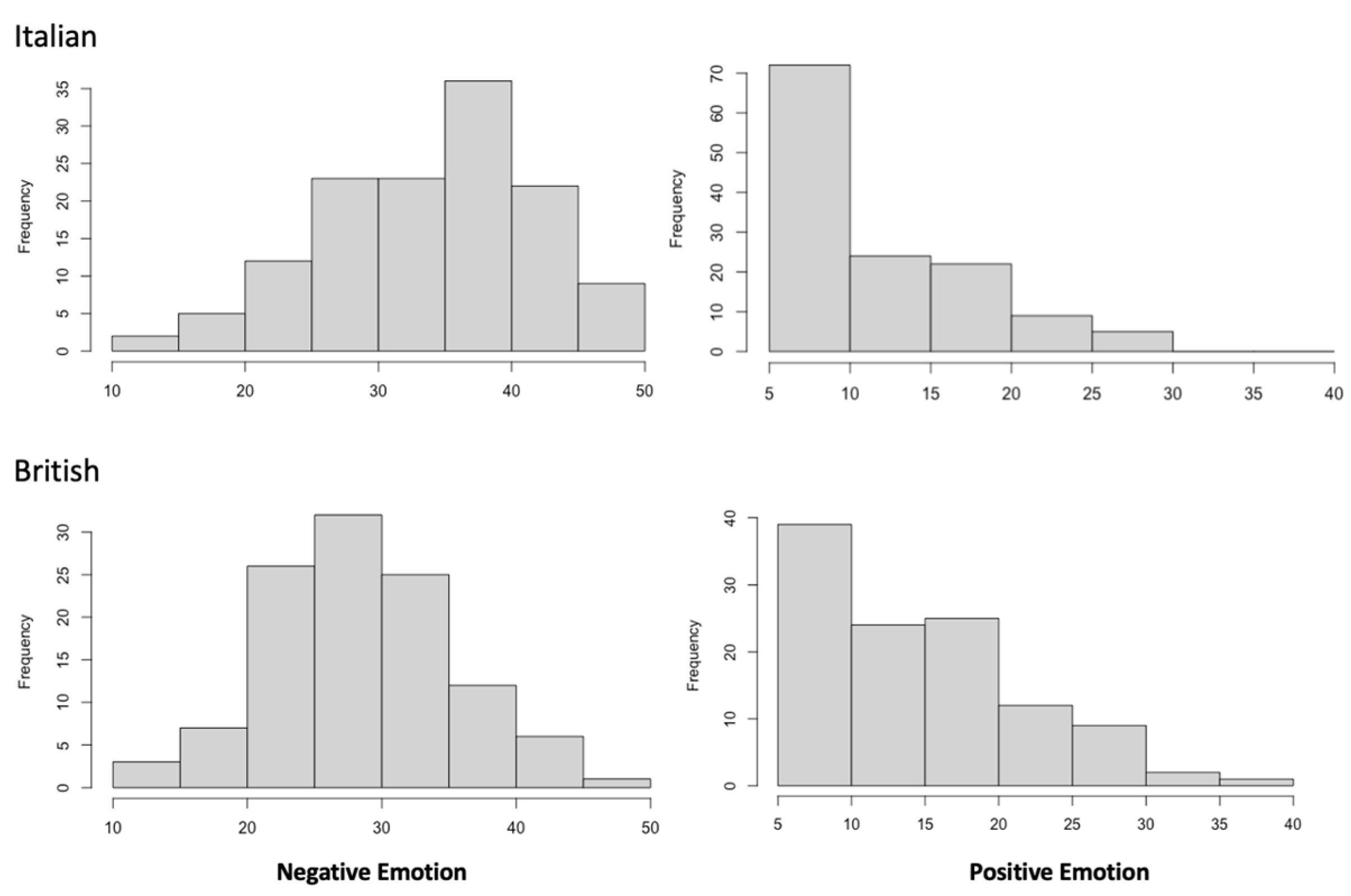

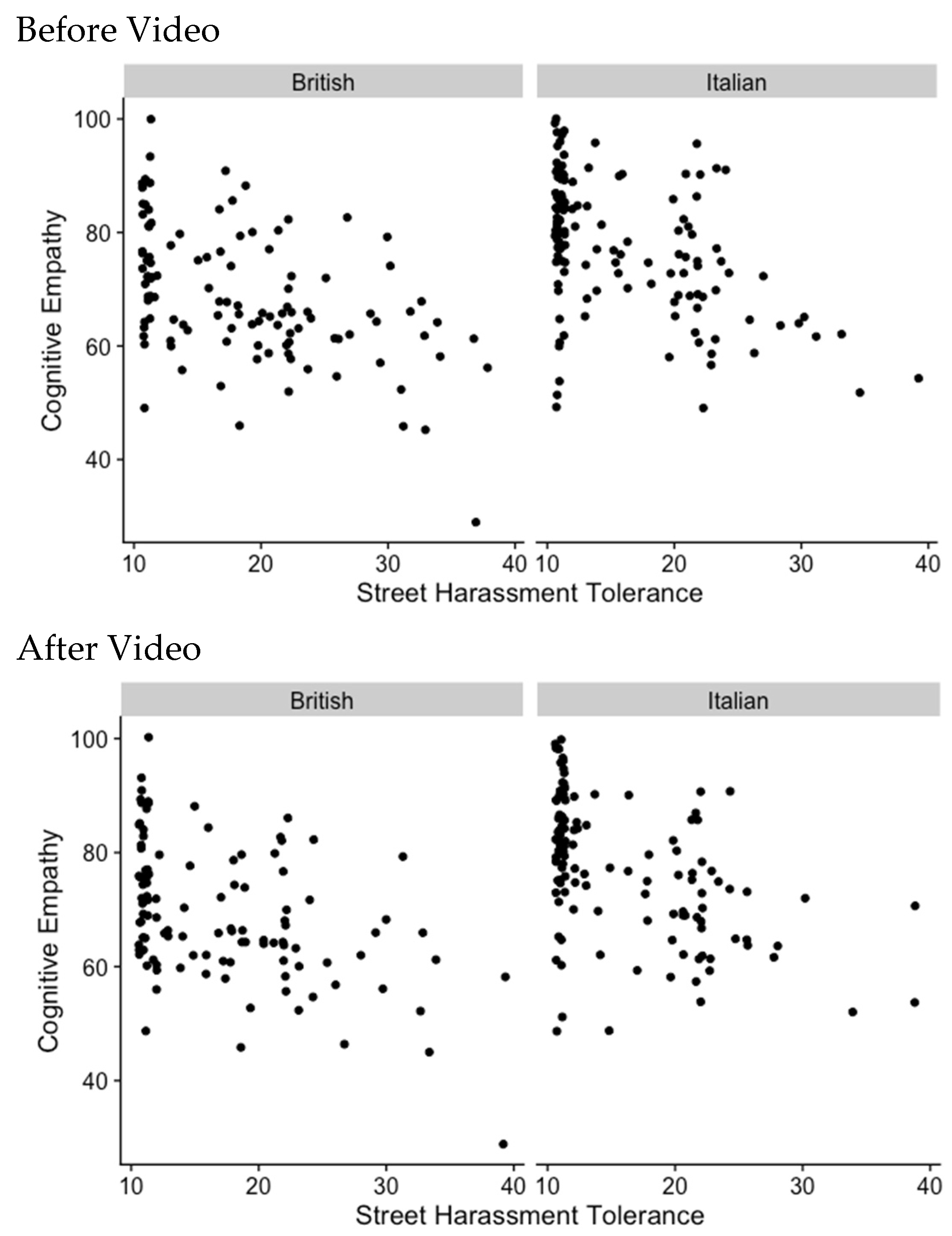

3.2.1. Cognitive Empathy

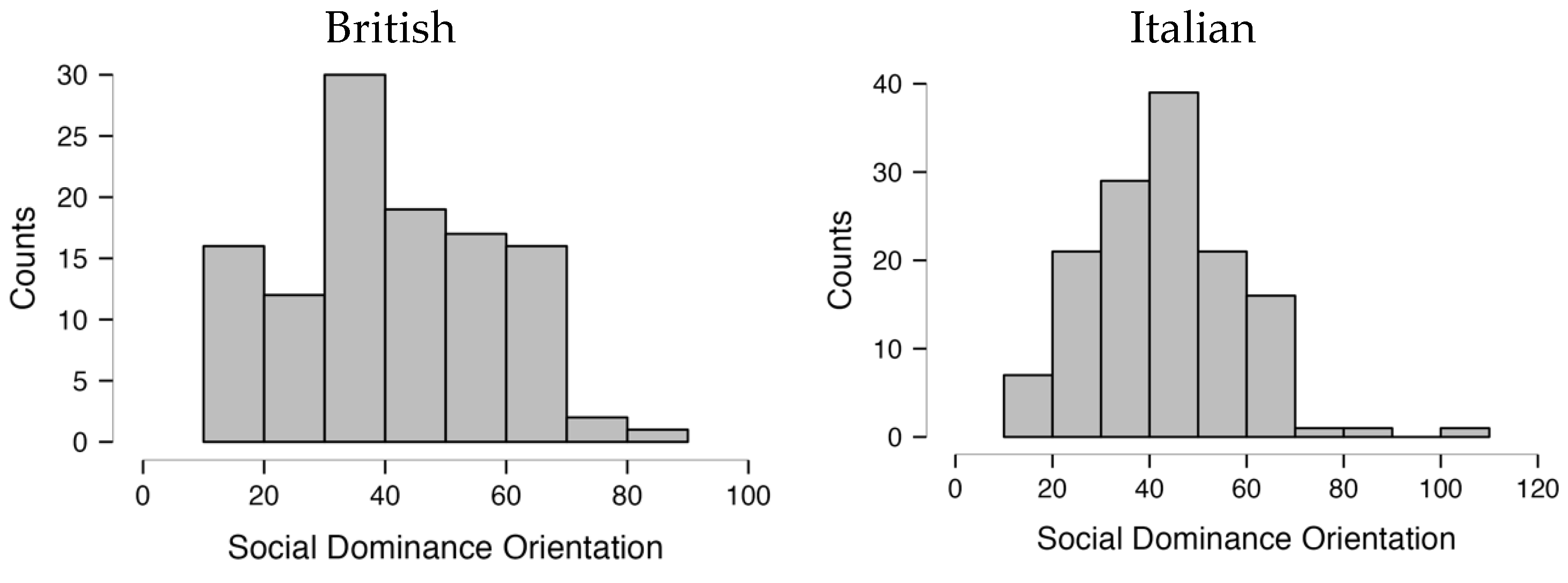

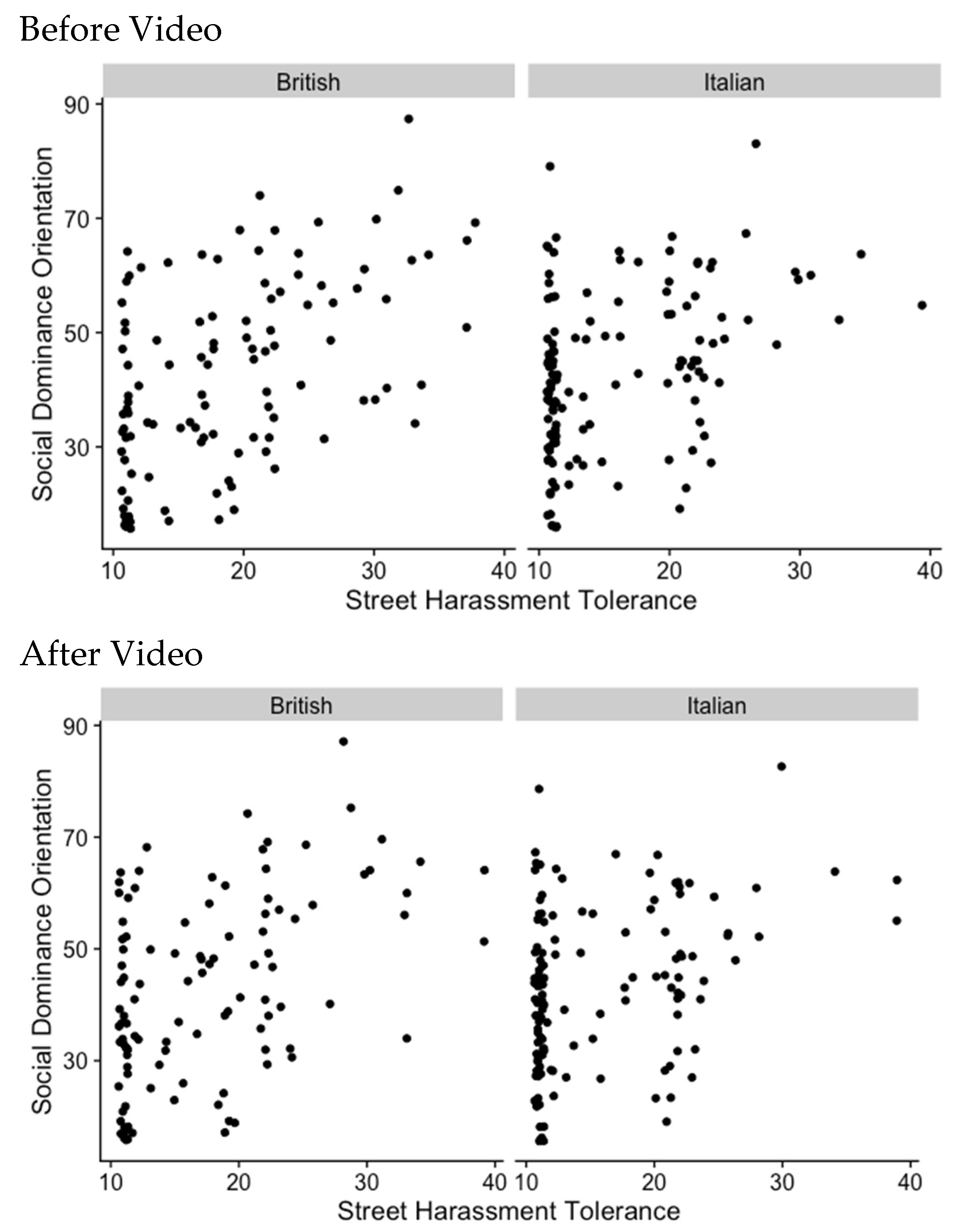

3.2.2. Social Dominance Orientation

3.3. Combined Model

3.4. Population Comparison

4. Discussion

Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviation

| SDO | Social Dominance Orientation |

Appendix A

| Italian | British | |

|---|---|---|

| Ever had a romantic relationship with a female | ||

| Yes | 102 | 93 |

| No | 28 | 18 |

| Rather not say | 6 | 2 |

| Ever had a meaningful relationship with a female | ||

| Yes | 125 | 105 |

| No | 9 | 7 |

| Rather not say | 2 | 0 |

| Gender composition of friendship group | ||

| Entirely male | 8 | 7 |

| Mostly male | 52 | 41 |

| A mix of gender | 59 | 61 |

| Mostly female | 17 | 4 |

| Entirely female | 0 | 0 |

| Cognitive Empathy | Before Video | After Video |

|---|---|---|

| British | ||

| Positive emotion | 0.68 | 0.66 |

| Negative emotion | −0.47 | −0.45 |

| Composite score | −0.46 | −0.45 |

| Italian | ||

| Positive emotion | 0.66 | 0.76 |

| Negative emotion | −0.60 | −0.72 |

| Composite score | −0.43 | −0.52 |

| Before Video | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| British Sample | |||||

| Variables | Model R2 | b | SE (b) | z | p |

| 0.43 | |||||

| (Constant) | 32.0 | 5.07 | 6.3 | <0.001 | |

| Cognitive empathy | −0.38 | 0.07 | −5.84 | <0.001 | |

| Social dominance orientation (SDO) | 0.26 | 0.04 | 6.08 | <0.001 | |

| Italian Sample | |||||

| Variables | Model R2 | b | SE (b) | z | p |

| 0.34 | |||||

| (Constant) | 31.3 | 6.1 | 5.1 | <0.001 | |

| Cognitive empathy | −0.38 | 0.07 | −5.5 | <0.001 | |

| Social dominance orientation (SDO) | 0.24 | 0.06 | 4.18 | <0.001 | |

| After Video | |||||

| British Sample | |||||

| Variables | Model R2 | b | SE (b) | z | p |

| 0.37 | |||||

| (Constant) | 30.0 | 5.5 | 5.4 | <0.001 | |

| Cognitive empathy | −0.38 | 0.07 | −5.3 | <0.001 | |

| Social dominance orientation (SDO) | 0.26 | 0.05 | 5.4 | <0.001 | |

| Italian Sample | |||||

| Variables | Model R2 | b | SE (b) | z | p |

| 0.34 | |||||

| (Constant) | 39.0 | 6.3 | 6.2 | <0.001 | |

| Cognitive empathy | −0.47 | 0.07 | −6.6 | <0.001 | |

| Social dominance orientation (SDO) | 0.20 | 0.06 | 3.4 | 0.001 | |

References

- Aiello, A., Passini, S., Tesi, A., Morselli, D., & Pratto, F. (2019). Measuring support for intergroup hierarchies: Assessing the psychometric proprieties of the Italian Social Dominance Orientation7 Scale. TPM-Testing, Psychometrics, Methodology in Applied Psychology, 26, 373–383. [Google Scholar]

- Bastomski, S., & Smith, P. (2017). Gender, fear, and public places: How negative encounters with strangers harm women. Sex Roles, 76(1–2), 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berdahl, J. L. (2007). Harassment based on sex: Protecting social status in the context of gender hierarchy. Academy of Management Review, 32(2), 641–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betts, L., Harding, R., Peart, S., Sjolin Knight, C., Wright, D., & Newbold, K. (2019). Adolescents’ experiences of street harassment: Creating a typology and assessing the emotional impact. Journal of Aggression, Conflict and Peace Research, 11(1), 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, E., & Gannon, T. (2008). Social perception deficits, cognitive distortions, and empathy deficits in sex offenders: A brief review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 9, 34–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bliss, R. (2014, October 28). 10 hours of walking in NYC as a woman. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b1XGPvbWn0A (accessed on 5 October 2021).

- Bosoni, M. L., & Baker, S. (2015). The intergenerational transmission of fatherhood: Perspectives from the UK and Italy. Families, Relationships and Societies, 4(2), 239–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M., McGrath, R. E., Bier, M. C., Johnson, K., & Berkowitz, M. W. (2023). A comprehensive meta-analysis of character education programs. Journal of Moral Education, 52(2), 119–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudoir, S. R., & Quinn, D. M. (2010). Bystander sexism in the intergroup context: The impact of cat-calls on women’s reactions towards men. Sex Roles, 62(9–10), 623–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112(1), 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crabtree, S., & Nsbuga, F. (2012, March 21). Women feel less safe than men in many developed countries. Gallup.Com. Women Feel Less Safe Than Men in Many Developed Countries. Available online: https://www.gallup.com (accessed on 15 November 2021).

- Darnell, A., & Cook, S. L. (2009). Investigating the utility of the film “War Zone” in the prevention of street harassment. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 33(3), 266–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DelGreco, M., & Christensen, J. (2020). Effects of street harassment on anxiety, depression, and sleep quality of college women. Sex Roles, 82(7–8), 473–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DelGreco, M., Ebesu Hubbard, A. S., & Denes, A. (2021). Communicating by catcalling: Power dynamics and communicative motivations in street harassment. Violence Against Women, 27(9), 1402–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Errico, F. (2019). ‘Too humble and sad’: The effect of humility and emotional display when a politician talks about a moral issue. Social Science Information, 58(4), 660–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diehl, C., Glaser, T., & Bohner, G. (2014). Face the consequences: Learning about victim’s suffering reduces sexual harassment myth acceptance and men’s likelihood to sexually harass. Aggressive Behavior, 40(6), 489–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- di Leonardo, M. (1981). The political economy of street harassment. Aegis, 51–57. [Google Scholar]

- Duckitt, J., & Sibley, C. G. (2010). Personality, ideology, prejudice, and politics: A dual-process motivational model. Journal of Personality, 78(6), 1861–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairchild, K., & Rudman, L. A. (2008). Everyday stranger harassment and women’s objectification. Social Justice Research, 21(3), 338–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, Y. M., & Marshall, W. L. (2003). Victim empathy, social self-esteem, and psychopathy in rapists. Sexual Abuse, 15(1), 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fileborn, B., & O’Neill, T. (2023). From “ghettoization” to a field of its own: A comprehensive review of street harassment research. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 24(1), 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fileborn, B., & Vera-Gray, F. (2017). “I want to be able to walk the street without fear”: Transforming justice for street harassment. Feminist Legal Studies, 25(2), 203–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, A. R., & Good, G. E. (1994). Gender, self, and others: Perceptions of the campus environment. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 41(3), 343–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B. L., & Roberts, T.-A. (1997). Objectification theory: Toward understanding women’s lived experiences and mental health risks. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21, 173–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gekoski, A., Gray, J. M., Adler, J. R., & Miranda, A. H. H. (2017). The prevalence and nature of sexual harassment and assault against women and girls on public transport: An international review. Journal of Criminological Research, Policy and Practice, 3(1), 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodchilds, J. D., & Zellman, G. L. (1984). Sexual signaling and sexual aggression in adolescent relationships. Pornography and Sexual Aggression, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halper, L. R., & Rios, K. (2019). Feeling powerful but incompetent: Fear of negative evaluation predicts men’s sexual harassment of subordinates. Sex Roles, 80(5–6), 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickman, S. E., & Muehlenhard, C. L. (1997). College women’s fears and precautionary behaviors relating to acquaintance rape and stranger rape. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21, 527–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, A. K., Sidanius, J., Kteily, N., Sheehy-Skeffington, J., Pratto, F., Henkel, K. E., Foels, R., & Stewart, A. L. (2015). The nature of social dominance orientation: Theorizing and measuring preferences for intergroup inequality using the new SDO7 scale. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 109(6), 1003–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Survey on Sexual Harassment in Public Spaces. (2021). Available online: https://righttobe.org/research/cornell-international-survey-on-street-harassment/ (accessed on 12 December 2021).

- Jacques-Tiura, A. J., Abbey, A., Parkhill, M. R., & Zawacki, T. (2007). Why do some men misperceive women’s sexual intentions more frequently than others do? An application of the confluence model. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 33(11), 1467–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jobe, J. B. (2003). Cognitive psychology and self-reports: Models and methods. Quality of Life Research, 12(3), 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolliffe, D., & Farrington, D. P. (2004). Empathy and offending: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 9(5), 441–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearl, H. (2014). Unsafe and harassed in public spaces: A national street harassment report. Available online: http://www.stopstreetharassment.org/ourwork/nationalstudy/ (accessed on 7 February 2022).

- Kunstman, J. W., & Maner, J. K. (2011). Sexual overperception: Power, mating motives, and biases in social judgment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 100(2), 282–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanier, C. A. (2001). Rape-accepting attitudes: Precursors to or consequences of forced sex. Violence Against Women, 7, 876–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenton, R., Smith, M. D., Fox, J., & Morra, N. (1999). Sexual harassment in public places: Experiences of Canadian women. The Canadian Review of Sociology, 36(4), 517–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macmillan, R., Nierobisz, A., & Welsh, S. (2000). Experiencing the streets: Harassment and perceptions of safety among women. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 37(3), 306–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarland, S. (2010). Authoritarianism, social dominance, and other roots of generalized prejudice. Political Psychology, 31(3), 453–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, P. A., & Eisenberg, N. (1988). The relation of empathy to aggressive and externalizing/antisocial behavior. Psychological Bulletin, 103, 324–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moya-Garófano, A., Moya, M., Megías, J. L., & Rodríguez-Bailón, R. (2022). Ambivalent sexism and women’s reactions to stranger harassment: The case of piropos in Spain. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 46(4), 454–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, L. B. (2002). Subtle, pervasive, harmful: Racist and sexist remarks in public as hate speech. Journal of Social Issues, 58(2), 265–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratto, F. (1994). Social dominance orientation: A personality variable predicting social and political attitudes. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 67(4), 741–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pryor, J. B. (1994). Sexual cognition processes in men high in the likelihood to sexually harass. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 20, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reilly, M. E., Lott, B., Caldwell, D., & DeLuca, L. (1992). Tolerance for sexual harassment related to self-reported sexual victimization. Gender & Society, 6, 122–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, B. L., & Trigg, K. Y. (2004). Tolerance of sexual harassment: An examination of gender differences, ambivalent sexism, social dominance, and gender roles. Sex Roles, 50(7–8), 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, B. A., Scaturro, C., Guarino, C., & Kelly, E. (2017). Contending with catcalling: The role of system-justifying beliefs and ambivalent sexism in predicting women’s coping experiences with (and men’s attributions for) stranger harassment. Current Psychology, 36, 324–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, N., & Oyserman, D. (2001). Asking questions about behavior: Cognition, communication, and questionnaire construction. The American Journal of Evaluation, 22(2), 127–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seal, D. W., & Ehrhardt, A. A. (2003). Masculinity and urban men: Perceived scripts for courtship, romantic, and sexual interactions with women. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 5(4), 295–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidanius, J., Kteily, N., Sheehy-Skeffington, J., Ho, A. K., Sibley, C., & Duriez, B. (2013). You’re inferior and not worth our concern: The interface between empathy and social dominance orientation. Journal of Personality, 81(3), 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smart, R. G. (1966). Subject selection bias in psychological research. Canadian Psychologist, 7(2), 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sportelli, C., Cicirelli, P. G., Paciello, M., Corbelli, G., & D’Errico, F. (2025). “Let’s make the difference!” Promoting hate counter-speech in adolescence through empathy and digital intergroup contact. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 35(1), e70028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockdale, M. S. (1993). The role of sexual misperceptions of women’s friendliness in an emerging theory of sexual harassment. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 42, 84–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera-Gray, F., & Kelly, L. (2020). Contested gendered space: Public sexual harassment and women’s safety work. International Journal of Comparative and Applied Criminal Justice, 44(4), 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogt, D., Bruce, T. A., Street, A. E., & Stafford, J. (2007). Attitudes toward women and tolerance for sexual harassment among reservists. Violence Against Women, 13(9), 879–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xilun Pang, H., & Tomlinson, M. K. (2023). The trivialization of sexual harassment in Japanese mascot culture: Japanese audience responses to YouTube videos of Kumamon. Feminist Media Studies, 23(7), 3533–3549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Highest Education Level | Italians | British | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| High School | 50 | 77 | 127 |

| Degree | 28 | 45 | 73 |

| Master | 22 | 17 | 39 |

| Ph.D. | 9 | 1 | 10 |

| Italian | British | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Street harassment tolerance | 11–55 | 16.76 | 8.01 | 18.88 | 7.71 |

| Cognitive empathy | 10–100 | 77.05 | 13.21 | 68.91 | 11.64 |

| Social dominance orientation | 16–112 | 61.64 | 7.96 | 68.30 | 7.96 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Giuliani, A.; Campbell-Meiklejohn, D. Predictors of Street Harassment Attitudes in British and Italian Men: Empathy and Social Dominance. Psychol. Int. 2025, 7, 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/psycholint7020028

Giuliani A, Campbell-Meiklejohn D. Predictors of Street Harassment Attitudes in British and Italian Men: Empathy and Social Dominance. Psychology International. 2025; 7(2):28. https://doi.org/10.3390/psycholint7020028

Chicago/Turabian StyleGiuliani, Alessandra, and Daniel Campbell-Meiklejohn. 2025. "Predictors of Street Harassment Attitudes in British and Italian Men: Empathy and Social Dominance" Psychology International 7, no. 2: 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/psycholint7020028

APA StyleGiuliani, A., & Campbell-Meiklejohn, D. (2025). Predictors of Street Harassment Attitudes in British and Italian Men: Empathy and Social Dominance. Psychology International, 7(2), 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/psycholint7020028