Abstract

Emojis are widely used to measure users’ emotional states; however, their interpretations can vary over time. While some emojis exhibit consistent meanings, others may be perceived differently at other times. To utilize emojis as indicators in consumer studies, it is essential to ensure that their interpretations remain stable over time. However, the long-term stability of emoji interpretations remains uncertain. Therefore, this study aims to identify emojis with stable and unstable interpretations. We collected 256 responses in an online survey twice, one week apart, in which participants rated the valence and arousal levels of 74 facial emojis on a nine-point scale. Wilcoxon rank-sum tests showed unstable interpretations for seven of the seventy-four emojis. Further, a hierarchical cluster analysis categorized 67 stable emojis into the following four clusters based on valence and arousal dimensions: strong positive sentiment, moderately positive sentiment, neutral sentiment, and negative sentiment. Consequently, we recommend the use of the 67 emojis with stable interpretations as reliable measures of emotional states in consumer studies.

1. Introduction

Emojis, a powerful non-verbal communication tool, are widely utilized worldwide to convey emotional states in daily communication. Recently, they have also been incorporated into research fields such as consumer studies to assess users’ emotions. For instance, human facial emojis have been employed to evaluate food products and gauge participants’ preferences (e.g., da Quinta et al., 2023; Jaeger et al., 2019; Jaeger et al., 2018). Compared to traditional text-based methods, emojis offer advantages such as ease of response and accessibility for individuals across different linguistic backgrounds. Therefore, a deeper understanding of how each emoji corresponds to specific human emotions can enhance their applicability in research.

In order for emojis to be used as appropriate indicators to assess users’ emotional responses, emojis need to be consistent with people’s emotions even at different times. Multiple studies in recent years have consistently shown that most emojis match well with people’s emotions (da Quinta et al., 2023; Jaeger et al., 2018, 2019; Kaneko et al., 2019; Kutsuzawa et al., 2022a, 2022b; Sick et al., 2020). For example, Kutsuzawa et al. (2022a) examined the interpretation of emotional states expressed by 74 emojis from the perspective of core affect among 1082 adults. They found that these emojis were classified into six groups based on core affect and correspond to various human emotions. Additionally, Jaeger et al. (2019) examined the emotional meanings of 33 emojis using open-ended questions among 1085 participants and found that these emojis were perceived as expressing a wide range of human emotions. However, all of these studies have evaluated the relationship between emojis and emotion only once and have never evaluated their stability over time. Schmid and Schmid Mast (2010) reported that the interpretation of human facial expressions is influenced by the interpreter’s mood at the time of assessment. This suggests that the interpretation of emojis may change from time to time. Therefore, the present study aimed to assess the stability of emoji interpretations over time.

The purpose of this study was, therefore, to understand the emojis with stable and unstable interpretations over time. A previous study indicated that the recognition of mood-incongruent expressions tends to be hampered, but neutral expressions were not affected by interpreters’ moods. Based on this, we hypothesize that emojis representing strong positive or strong negative emotions are more likely to have unstable interpretations over time, as they may be more influenced by the respondent’s mood at the time of assessment. To test this hypothesis, participants were asked to interpret the same emojis twice, with a one-week interval, and the consistency of their responses was analyzed. Emojis that exhibited a statistically significant difference between the two responses were considered to have an unstable interpretation, while those without a significant difference were deemed stable. In this study, young adults were selected as participants for the following three reasons: (1) Prior research has exhibited that emoji interpretations tend to differ between young and middle-aged adults (Kutsuzawa et al., 2022b); (2) Young adults are the largest users of emojis compared to other age groups (Evans, 2015); (3) As the first study to examine the stability of emoji interpretation over time, it is essential to establish fundamental findings prior to expanding to other demographics.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

An online survey was conducted in Tokyo, Japan, involving 256 valid participants aged 20–39 years (responses were collected to ensure no gender bias). A review by Oshio (2016) on the stability of psychological indicator interpretation noted that most previous research has been conducted with fewer than 300 subjects. Therefore, the sample size for this study was set at approximately 250, and the data was obtained from an online research company. The participants were recruited from an online panel maintained by a marketing research firm (https://candc.co.jp/) and received an honorarium of JPY 200 (approximately USD 1.3). All participants were fluent in Japanese, the language of the survey. Ethical approval was obtained prior to data collection, and eligible participants were informed about data confidentiality. Informed consent was obtained online prior to their participation in the study. This study was conducted in accordance with the World Medical Association’s Declaration of Helsinki, and all study protocols were reviewed and determined that an ethical review was not required for this study by the local institutional review board (Committee on Ergonomic Experiments of the National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology).

2.2. Emojis Used in This Study

This study utilized human facial emojis, similar to those employed in prior studies (Jaeger et al., 2019; Kutsuzawa et al., 2022a, 2022b), as facial emojis are the most commonly utilized category (Swiftkey, 2015). To build upon prior studies exploring emojis as an emotion measurement index, we selected the same emojis utilized in prior studies (Kutsuzawa et al., 2022a, 2022b). Specifically, out of the 89 facial emojis available on Twemoji, 74 were selected. We excluded 15 (e.g., 🤒 and 🤕) owing to difficulties in defining their emotional meanings during the preliminary survey (see the Supplementary Materials for more information). Since emoji designs vary slightly across platforms (e.g., Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, and WhatsApp), this study utilized Twitter’s emoji designs, as their graphics license is clearly defined (licensed under CC-BY 4.0: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ (accessed on 8 January 2025)). The emojis were saved as image files and displayed on a screen at an appropriate size (2.16 × 2.16 cm) to ensure clarity. To prevent bias in participant evaluations, no additional information (e.g., emoji labels) was provided.

2.3. Questionnaire

The survey was administered to the same participants on two occasions, with a one-week interval between sessions. The first session collected data on participants’ sociodemographic characteristics and assessed their valence and arousal ratings for each emoji, following the methodology of prior studies (Jaeger et al., 2019; Kutsuzawa et al., 2022a, 2022b). For emoji interpretation, participants responded to the prompt “Please tell us your intended emotional state when using the following emojis in daily life (messages, social networking, etc.)”. Then they rated each emoji on a nine-point Likert scale for valence (“Do you think the emotions indicated by the emojis are pleasant or unpleasant?” where 1 = displeasure and 9 = pleasure) and arousal (“How much emotional intensity do you think the emojis express?” where 1 = weak and 9 = strong). To minimize the participant workload, each individual rated only 30 out of the 74 emojis. To ensure balanced data collection across all emojis, 16 predefined presentation patterns were created and participants were randomly assigned to one of these patterns. After one week, participants rated the same set of emojis again for valence and arousal. Each emoji was evaluated by a minimum of 96 participants.

To verify response validity, two dummy questions were included after every 10 questions (i.e., Questions 11 and 21) following Miura and Kobayashi (2015). These questions were designed to be easily answerable if the instructions were properly understood (e.g., “What is the subject of this questionnaire that you are being asked to answer?”). Participants who provided incorrect responses to these questions were excluded from the study.

2.4. Data Analysis

To examine the stability of emoji interpretations over time, Wilcoxon rank-sum tests were conducted to compare valence and arousal scores across sessions for each emoji. This approach was chosen because several studies recommended utilizing non-parametric tests for Likert scale data, as the intervals between response options (e.g., between 1 and 2, or between 2 and 3) are not strictly equal (e.g., Kuzon et al., 1996; Jamieson, 2004). Results were considered statistically significant if the p-values were less than 0.05 and the effect size (r) exceeded 0.30.

Furthermore, to classify emojis with stable interpretations into distinct clusters, hierarchical cluster analysis was conducted on the valence and arousal ratings of each emoji. The analysis employed Euclidean distance and Ward’s aggregation criterion, with Z-scores computed for each rating prior to implementation. The optimum number of clusters was determined utilizing a dendrogram and the Calinski and Harabasz index 11, following the methodology of a prior study. After clustering, valence and arousal scores were compared across clusters using Kruskal–Wallis tests. When a significant main effect was detected, post hoc analysis was conducted utilizing the Bonferroni correction. Kruskal–Wallis tests results were considered statistically significant if the p-values were less than 0.05.

All the statistical analyses except for the Calinski–Harabasz index calculation were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 26 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The Calinski–Harabasz index was calculated using R software (R Development Core Team).

3. Results

3.1. Analyzed Data and Emojis with Stable Interpretation

Data from 256 participants (128 men and 128 women; M age = 29.63 years; SD = 5.61) were analyzed. As a result of statistical analyses, no significant differences were found in either valence or arousal for 67 emojis, and significant differences were found in either or both valence or/and arousal for seven emojis, as shown in Table 1 and Table 2.

Table 1.

List of facial emojis whose interpretations were stable.

Table 2.

List of facial emojis whose interpretations were unstable.

3.2. Classifications of Stable Emojis

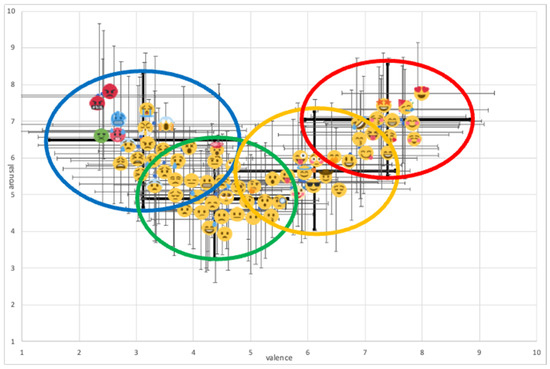

Based on the results of a cluster analysis, a four-cluster solution was retained as exhibited in Figure 1. The horizontal axis represents the valence level, while the vertical axis represents the arousal level. The error bars in the figure indicate one standard deviation for each variable (i.e., valence and arousal). Additionally, each colored circle represents the range of ± 1 standard deviation from the mean valence and arousal for each cluster. The dendrogram produced by cluster analysis is shown in Figure S2. Among the four clusters, a significant main effect was found in the valence (χ2(3) = 58.249, p < 0.001) and arousal levels (χ2(3) = 54.232, p < 0.001), and post hoc analysis revealed the independence of all clusters on the two axes (ps < 0.05).

Figure 1.

The core affect overlaid for each cluster on the scatter plot of the mean arousal and valence scores for the 67 facial emojis. The vertical and horizontal axes represent the valence and arousal levels, respectively. The error bars indicate one standard deviation for each variable (i.e., valence and arousal). Additionally, each colored circle represents the range of ± 1 standard deviation from the mean valence and arousal for each cluster.

4. Discussion

This research aimed to identify emojis with stable and unstable interpretations over time in order to provide insights for consumer surveys using emojis as an indicator. We initially hypothesized that emojis that represent strong positive or strong negative emotions tend to be more unstable in interpretation over time. As a result of two online surveys, one week apart, we found significant statistical differences in either valence or arousal, or both, between surveys for seven emojis listed in Table 2. Of the seven emojis with unstable interpretations, six of them (🥰, 😆, 😉, 🤗, 😀, and 🙂) represent strong positive emotions, as all of them have an average valence of six or higher in the two surveys. The one remaining unstable emoji (☹️) represents a strong negative emotion, as indicated by an average valence of less than four in the two surveys. These results partially support our initial hypothesis and allow us to conclude that these emojis are not suitable to use as indicators for consumer surveys because they can be interpreted in different ways over time.

One reason for the discrepancy between our initial hypothesis and the results of our study may be due to the cultural characteristics of Japanese participants. It has been reported that Japanese individuals are more attuned to negative emotions in ambiguous facial expressions and demonstrate higher accuracy in recognizing negative facial expressions compared to individuals from other countries, due to their cultural characteristics (Cao & Taka, 2020). Therefore, when using emojis as indicators in consumer surveys targeting Japanese individuals, it would be important to use emojis that represent clear positive emotions.

The 67 emojis with stable interpretations distributed in a U-shape on the two axes (valence and arousal), are similar to those used in the previous studies (Kutsuzawa et al., 2022a, 2022b) (Figure 1). A hierarchical cluster analysis classified 67 emojis into the following four clusters. In cluster 1, the following 11 emojis are classified: 😄, 😁, 🤣, 😊,  , 😍, 😘, 😚, 😝, 🥳 and 🤩. Because both average valence and arousal were greater than 7, this cluster can be interpreted as “strong positive sentiment”. In cluster 2, the following 14 emojis are classified: 😃, 😇, 😋, 😌, 😙, 😜, 😛, 😎, 🤠, 🤡, 🤔, 🤭, 😳 and 😮. Average valence was 6.12 and average arousal was 5.66. Therefore, this cluster can be interpreted as “moderately positive sentiment”. In cluster 3, the following 21 emojis are classified: 😅, 🧐, 😶, 😐, 😑, 😒, 🙄, 🤨, 😞, 😔, 😕, 🙁, 😬, 🥺, 😨, 😧, 😪, 😓, 🥴, 😲 and 😗. Average valence was 4.37 and average arousal was 4.89. Therefore, this cluster can be interpreted as “neutral sentiment”. Finally, in cluster 4, the following 19 emojis are classified: 😟, 😠, 😡, 🤬, 😣, 😖, 😫, 😩, 😤, 😱, 😰, 😢, 😥, 😭, 😵, 🤯, 🤢, 🥵 and 🥶. From the low average valence (3.12) and high average arousal (6.49), this cluster can be interpreted as “negative sentiment”.

, 😍, 😘, 😚, 😝, 🥳 and 🤩. Because both average valence and arousal were greater than 7, this cluster can be interpreted as “strong positive sentiment”. In cluster 2, the following 14 emojis are classified: 😃, 😇, 😋, 😌, 😙, 😜, 😛, 😎, 🤠, 🤡, 🤔, 🤭, 😳 and 😮. Average valence was 6.12 and average arousal was 5.66. Therefore, this cluster can be interpreted as “moderately positive sentiment”. In cluster 3, the following 21 emojis are classified: 😅, 🧐, 😶, 😐, 😑, 😒, 🙄, 🤨, 😞, 😔, 😕, 🙁, 😬, 🥺, 😨, 😧, 😪, 😓, 🥴, 😲 and 😗. Average valence was 4.37 and average arousal was 4.89. Therefore, this cluster can be interpreted as “neutral sentiment”. Finally, in cluster 4, the following 19 emojis are classified: 😟, 😠, 😡, 🤬, 😣, 😖, 😫, 😩, 😤, 😱, 😰, 😢, 😥, 😭, 😵, 🤯, 🤢, 🥵 and 🥶. From the low average valence (3.12) and high average arousal (6.49), this cluster can be interpreted as “negative sentiment”.

, 😍, 😘, 😚, 😝, 🥳 and 🤩. Because both average valence and arousal were greater than 7, this cluster can be interpreted as “strong positive sentiment”. In cluster 2, the following 14 emojis are classified: 😃, 😇, 😋, 😌, 😙, 😜, 😛, 😎, 🤠, 🤡, 🤔, 🤭, 😳 and 😮. Average valence was 6.12 and average arousal was 5.66. Therefore, this cluster can be interpreted as “moderately positive sentiment”. In cluster 3, the following 21 emojis are classified: 😅, 🧐, 😶, 😐, 😑, 😒, 🙄, 🤨, 😞, 😔, 😕, 🙁, 😬, 🥺, 😨, 😧, 😪, 😓, 🥴, 😲 and 😗. Average valence was 4.37 and average arousal was 4.89. Therefore, this cluster can be interpreted as “neutral sentiment”. Finally, in cluster 4, the following 19 emojis are classified: 😟, 😠, 😡, 🤬, 😣, 😖, 😫, 😩, 😤, 😱, 😰, 😢, 😥, 😭, 😵, 🤯, 🤢, 🥵 and 🥶. From the low average valence (3.12) and high average arousal (6.49), this cluster can be interpreted as “negative sentiment”.

, 😍, 😘, 😚, 😝, 🥳 and 🤩. Because both average valence and arousal were greater than 7, this cluster can be interpreted as “strong positive sentiment”. In cluster 2, the following 14 emojis are classified: 😃, 😇, 😋, 😌, 😙, 😜, 😛, 😎, 🤠, 🤡, 🤔, 🤭, 😳 and 😮. Average valence was 6.12 and average arousal was 5.66. Therefore, this cluster can be interpreted as “moderately positive sentiment”. In cluster 3, the following 21 emojis are classified: 😅, 🧐, 😶, 😐, 😑, 😒, 🙄, 🤨, 😞, 😔, 😕, 🙁, 😬, 🥺, 😨, 😧, 😪, 😓, 🥴, 😲 and 😗. Average valence was 4.37 and average arousal was 4.89. Therefore, this cluster can be interpreted as “neutral sentiment”. Finally, in cluster 4, the following 19 emojis are classified: 😟, 😠, 😡, 🤬, 😣, 😖, 😫, 😩, 😤, 😱, 😰, 😢, 😥, 😭, 😵, 🤯, 🤢, 🥵 and 🥶. From the low average valence (3.12) and high average arousal (6.49), this cluster can be interpreted as “negative sentiment”.This study has several limitations that must be acknowledged when interpreting the results. First, some readers may point out the relatively small sample size of this study. As described above, we asked 96 to 112 participants to evaluate each emoji. A small sample size may affect the results of a statistical analysis. Therefore, we conducted a post hoc power analysis based on the sample size and effect size of the results. As a result, we found that the power of the test was 81.1% for 96 participants and 86.7% for 112 participants. Accordingly, we can interpret that the sample size of this experiment is sufficient to detect significant differences. Second, all the participants of this study were Japanese individuals aged 20 to 39 years. The interpretation of emojis may be influenced by various factors, such as age (Kutsuzawa et al., 2022b), culture (Jaeger et al., 2019; Kaneko et al., 2019; Kralj Novak et al., 2015), and experience with daily IoT device usage. Therefore, readers should be aware of these factors when applying the findings of this study to consumer research. Third, this study used an online survey to identify the stability of emoji interpretation, although the same emoji could have different meanings in different social situations and seasons (da Quinta et al., 2023; Robertson et al., 2021). More importantly, this study did not examine the ecological validity of emoji interpretation and responsiveness. To effectively utilize emojis as indicators of users’ emotional states in psychology and consumer research, it is essential to identify emojis that are suitable for measuring emotions in everyday life and capable of detecting significant changes. Therefore, future studies should address these aspects to enhance the applicability of emojis as reliable indicators in consumer studies.

5. Conclusions

This study attempted to clarify the stability of emoji interpretation. The results demonstrated that facial emojis are a mixture of emojis with stable and unstable interpretations. We classified 67 of the 74 emojis with stable interpretations into four clusters on valence and arousal axes. These included (1) negative sentiment, (2) neutral sentiment, (3) moderately positive sentiment, and (4) strong positive sentiment clusters. We concluded that emojis correspond stably to detailed human emotions. The results of this study support the potential of utilizing emojis to measure emotions and suggest their applicability beyond food research to various contexts, including everyday situations where emotions need to be assessed easily.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/psycholint7010027/s1. Figure S1: The core affect overlaid for each cluster on the scatter plot of the mean arousal and valence scores for the 74 facial emojis in (S1a) first and (S1b) second sessions. Vertical and horizontal axes represent the valence and arousal levels, respectively. Error bars indicate one standard deviation for each variable (i.e., valence and arousal). Each colored circle represents the range of ±1 standard deviation from the mean emotional valence and mean arousal for each cluster. Brackets in the bars indicate the number of emojis belonging to each cluster, which is equal in (S1a) and (S1b). Figure S2: The dendrogram of the mean valence and arousal scores for the 67 emoji for which no significant differences (S2a). The Calinski and Harabasz index of the mean valence and arousal scores for the 67 emoji for which no significant differences (S2b). The orange line represents The Calinski and Harabasz index, and the light blue line represents the WSS produced in the process of calculating The Calinski and Harabasz index. Table S1: Cluster 1 and 2’s emoji collection (i.e., strong positive sentiment and moderately positive sentiment). Figures in parentheses are standard deviations. Table S2: Cluster 3’s emoji collection (i.e., neutral sentiment). Figures in parentheses are standard deviations. Table S3: Cluster 4’s emoji collection (i.e., negative sentiment). Figures in parentheses are standard deviations.

Author Contributions

G.K. and Y.K. performed the experiments. G.K. analyzed the data. H.U., K.E. and Y.K. provided guidance and oversight. G.K. and Y.K. drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to notes and edits in the manuscript and provided critical feedback in improving the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was partly supported by JSPS KAKENHI, Grant Number 19K12918.

Institutional Review Board Statement

We conducted non-interventional research utilizing self-reported questionnaires without directly manipulating participants. Informed consent was obtained from participants, ensuring that their data would be utilized solely for research purposes and kept strictly anonymous. We upheld the principles of human dignity and participant welfare. The local institutional review board (Committee on Ergonomic Experiments of the National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology) determined that an ethical review was not required for this study, but advised adherence to guidelines and forms supporting ethical research implementation.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the participants in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Cao, L., & Taka, F. (2020). Cultural comparison between Chinese and Japanese people’s perception of emotions. Japanese Journal of Psychology, 91, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Quinta, N., Santa Cruz, E., Rios, Y., Alfaro, B., & de Marañón, I. M. (2023). What is behind a facial emoji? The effects of context, age, and gender on children’s understanding of emoji. Food Quality and Preference, 105, 104761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, V. (2015). No, the rise of the emoji doesn’t spell the end of language. Available online: https://theconversation.com/no-the-rise-of-the-emoji-doesnt-spell-the-end-of-language-42208 (accessed on 27 February 2025).

- Jaeger, S. R., Roigard, C. M., Jin, D., Vidal, L., & Ares, G. (2019). Valence, arousal and sentiment meanings of 33 facial emoji: Insights for the use of emoji in consumer research. Food Research International, 119, 895–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaeger, S. R., Xia, Y., Lee, P. Y., Hunter, D. C., Beresford, M. K., & Ares, G. (2018). Emoji questionnaires can be used with a range of population segments: Findings relating to age, gender and frequency of emoji/emoticon use. Food Quality and Preference, 68, 397–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamieson, S. (2004). Likert scales: How to (ab) use them? Medical Education, 38(12), 1217–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaneko, D., Toet, A., Ushiama, S., Brouwer, A. M., Kallen, V., & van Erp, J. B. (2019). EmojiGrid: A 2D pictorial scale for cross-cultural emotion assessment of negatively and positively valenced food. Food Research International, 115, 541–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kralj Novak, P., Smailović, J., Sluban, B., & Mozetič, I. (2015). Sentiment of emojis. PLoS ONE, 10(12), e0144296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kutsuzawa, G., Umemura, H., Eto, K., & Kobayashi, Y. (2022a). Classification of 74 facial emoji’s emotional states on the valence-arousal axes. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kutsuzawa, G., Umemura, H., Eto, K., & Kobayashi, Y. (2022b). Age differences in the interpretation of facial emojis: Classification on the arousal-valence space. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 915550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuzon, W., Urbanchek, M., & McCabe, S. (1996). The seven deadly sins of statistical analysis. Annals of Plastic Surgery, 37, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miura, A., & Kobayashi, T. (2015). Mechanical Japanese: Survey satisficing of online panels in Japan. The Japanese Journal of Social Psychology, 31(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshio, S. (2016). Evaluation of test-retest reliability in the development of psychological scales: A meta-analysis of correlation coefficients described in the Japanese Journal of Psychology. Japanese Psychological Review, 59, 68–83. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, A., Liza, F. F., Nguyen, D., McGillivray, B., & Hale, S. A. (2021, June 7). Semantic journeys: Quantifying change in emoji meaning from 2012–2018. 4th International Workshop on Emoji Understanding and Applications in Social Media, Online. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, P. C., & Schmid Mast, M. (2010). Mood effects on emotion recognition. Motivation and Emotion, 34, 288–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sick, J., Monteleone, E., Pierguidi, L., Ares, G., & Spinelli, S. (2020). The meaning of emoji to describe food experiences in pre-adolescents. Foods, 9(9), 1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swiftkey. (2015). Emoji report 2015. Available online: http://emoji.com/report.php (accessed on 30 October 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).