Abstract

Owner-led self-medication for companion animals is a growing global practice; however, empirical data from Japan remain limited. Framing medication safety within a One Health perspective, this study aimed to characterize Japanese pet owners’ use of over-the-counter (OTC) drugs and identify possibilities for pharmacists to support rational self-medication. A cross-sectional 13-item online survey was administered to 500 owners in Japan between 30 May and 2 June 2025. Data on owner demographics, willingness to consult pharmacists, veterinary visit behavior, and OTC purchasing practices were summarized. Many owners were receptive to pharmacy support; 65% wished to consult a pharmacist, and 6.8% had already done so. Overall, 15.2% reported using OTCs drugs, primarily for treatment or prevention and prioritized perceived effectiveness and safety when selecting products. Some owners managed mild pet illnesses at home, citing perceived mildness and cost as reasons for not visiting a veterinary clinic. There is an unmet demand for accessible expert counseling at the point of purchase. Leveraging community pharmacies linked with pet specialty pharmacies as first-contact hubs could promote appropriate self-medication; doing so would require veterinary-specific training, establishing a formal credential for veterinary pharmacists, and defining pharmacist–veterinarian communication to ensure safe and effective use.

1. Introduction

The responsible use of pharmaceuticals, both in human and veterinary medicine, has become increasingly important as healthcare advances. Pet self-medication broadly refers to the administration of treatment to companion animals by their owners without direct veterinary supervision. While wild animals may instinctively self-treat ailments with natural substances, domestic pets rely entirely on human caregivers for medication [1]. With growing global pet ownership, there has been increasing concern regarding pet owners’ independent medication use, driven by convenience, cost savings, and availability through non-veterinary channels, such as community pharmacies and online platforms [2,3,4]. Such practices carry risks, including inappropriate dosing, adverse drug reactions, and exacerbation of antimicrobial resistance owing to improper antibiotic use [5,6].

Veterinary pharmaceutical care has significantly evolved. Studies from the United States have reported widespread dispensing of pet medications through community pharmacies, with pharmacists often involved in providing medication guidance to pet owners [3,4]. In contrast, Japan’s veterinary medication landscape remains predominantly veterinarian-centric, with medications typically prescribed and dispensed directly in veterinary clinics. Pet pharmaceuticals, including over-the-counter (OTC) medications, remain limited outside clinical settings, and the involvement of pharmacists in animal care is rare. Recent studies have indicated a growing interest among Japanese veterinary professionals in integrating pharmacists into veterinary practice to enhance pharmaceutical care; however, this trend remains at an early stage, and such integration is limited [7,8]. To date, detailed empirical evidence on Japanese pet owners’ actual purchasing behaviors and medication management practices remains insufficient. We hypothesized that pet self-medication practices differ between Japan and other countries because of the variations in access to veterinary pharmaceuticals and extent of the involvement of pharmacists in medication supply, resulting in increased owner-driven decision-making in Japan.

Therefore, this study aimed to elucidate the current practices and attitudes surrounding pet medication purchases and self-medication behaviors among Japanese pet owners and explore the potential roles of pharmacists in enhancing veterinary pharmaceutical care.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Survey Design

The companion animals used in this study were dogs and cats, which are common pets in Japan. This study employed a cross-sectional descriptive design using an online questionnaire to investigate pet owners’ behaviors and attitudes toward the purchase and use of OTC medications for companion animals in Japan. The survey focused on OTC medications that do not involve veterinary prescriptions. This study was conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee for Life Science and Medical Research of the Tohoku Medical and Pharmaceutical University (Ethics Review Number: 2025-A-002-0000).

2.2. Questionnaire Structure

The questionnaire consisted of 13 items divided into three main categories: (1) basic demographic information (e.g., pet type and owner age), (2) experiences and attitudes toward consulting pharmacists regarding pet medications, and (3) purchasing behaviors and decision-making factors related to OTC veterinary drugs. The specific themes included purposes of medication use, sources of information, purchasing channels, product selection criteria, and estimated expenditure. The questionnaire combines multiple-choice and open-ended questions. The complete questionnaire is available in the Supplementary Materials (Questionnaire S1).

2.3. Study Participants and Data Collection

The target population consisted of individuals aged ≥18 years residing in Japan who were currently caring for ≥1 companion animal (dogs, cats, or both). Participants were selected from a panel of registered monitors maintained by the web-based survey company Cross Marketing Inc. (Tokyo, Japan; https://www.cross-m.co.jp/, accessed on 16 April 2025.). The survey was launched on 30 May 2025, with a target sample size of 500 participants. The target number of respondents (500) was calculated to ensure representativeness based on population estimates. Using a 95% confidence level and a 5% margin of error, the minimum required sample size was calculated to be 385; therefore, the target sample size was set at 500 to increase precision. For exploratory species-stratified analyses, we compared dog-only and cat-only owners. Responses were collected via a dedicated web-based platform managed by the survey company Cross Marketing Inc. Invitations were distributed electronically to eligible panel members; no advertisements were made through veterinarians, TV, or other media. Eligible participants were screened based on the above criteria, and only those who provided informed consent were permitted to undertake the survey. All participants were informed that their responses would be anonymized and used solely for research purposes.

3. Results

The target sample size of 500 participants was reached four days later, on 2 June 2025.

3.1. Demographic Characteristics of Pet Owners

Among 500 respondents, 49.2% owned dogs, 42.0% owned cats, and 8.8% owned both (Table 1). Most responders were aged 40–59 years (49.4%), followed by those aged 60–79 years (36.8%) and 20–39 years (13.4%). Younger (18–19 years) and older (≥80 years) respondents were rare (0.2% each).

Table 1.

Characteristics of pet owners.

3.2. Willingness to Consult Pharmacists About Pet Medications

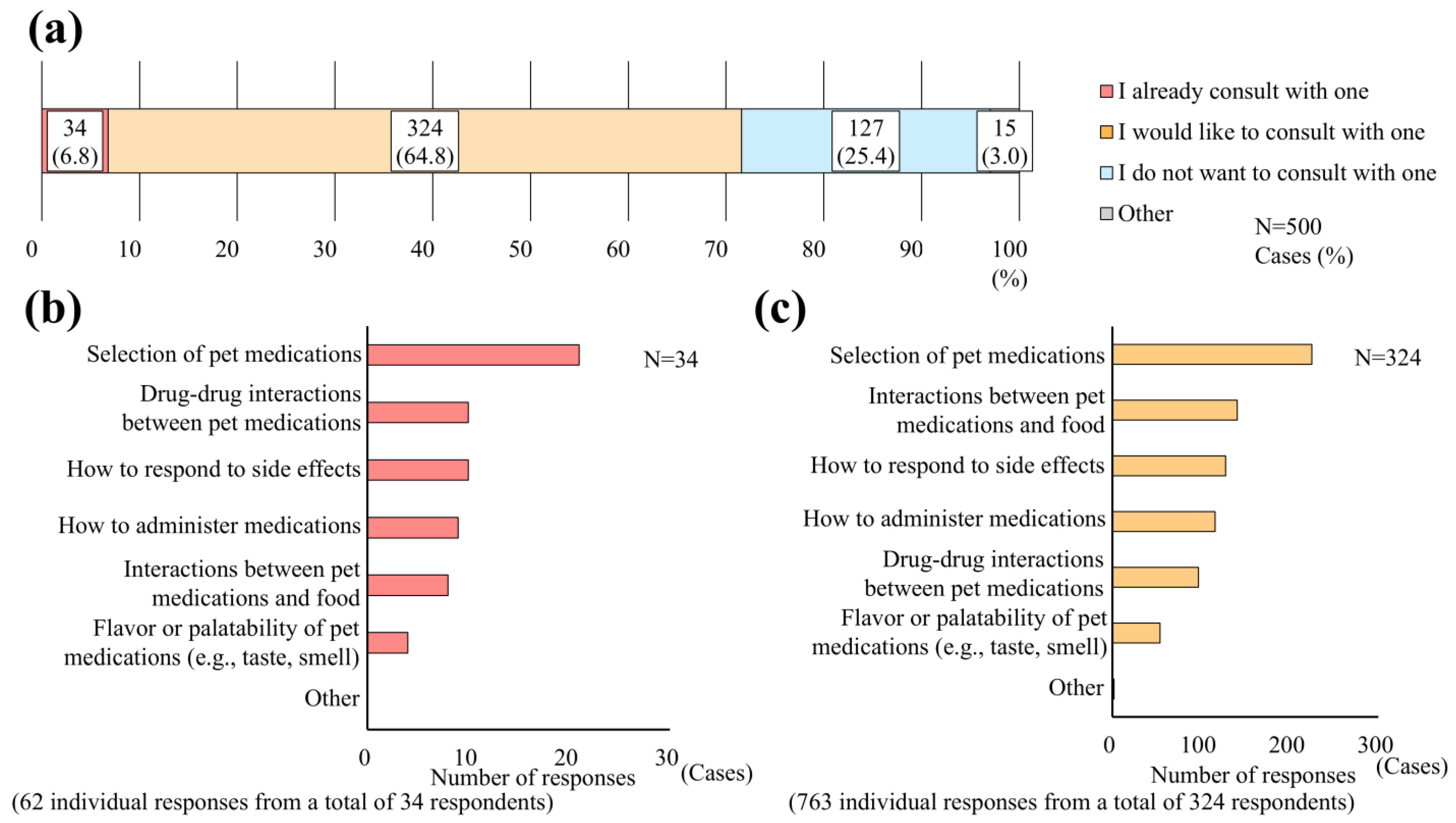

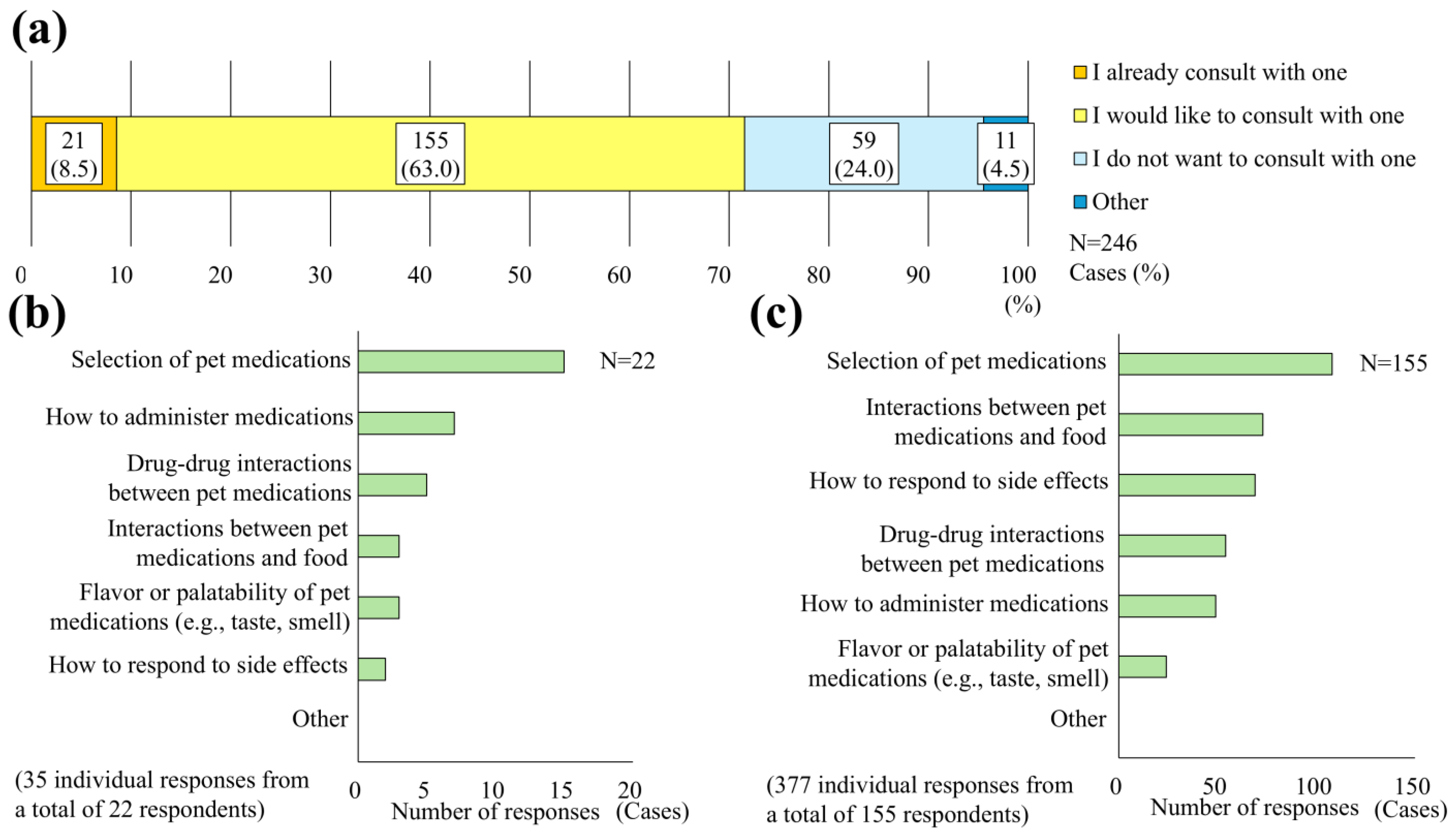

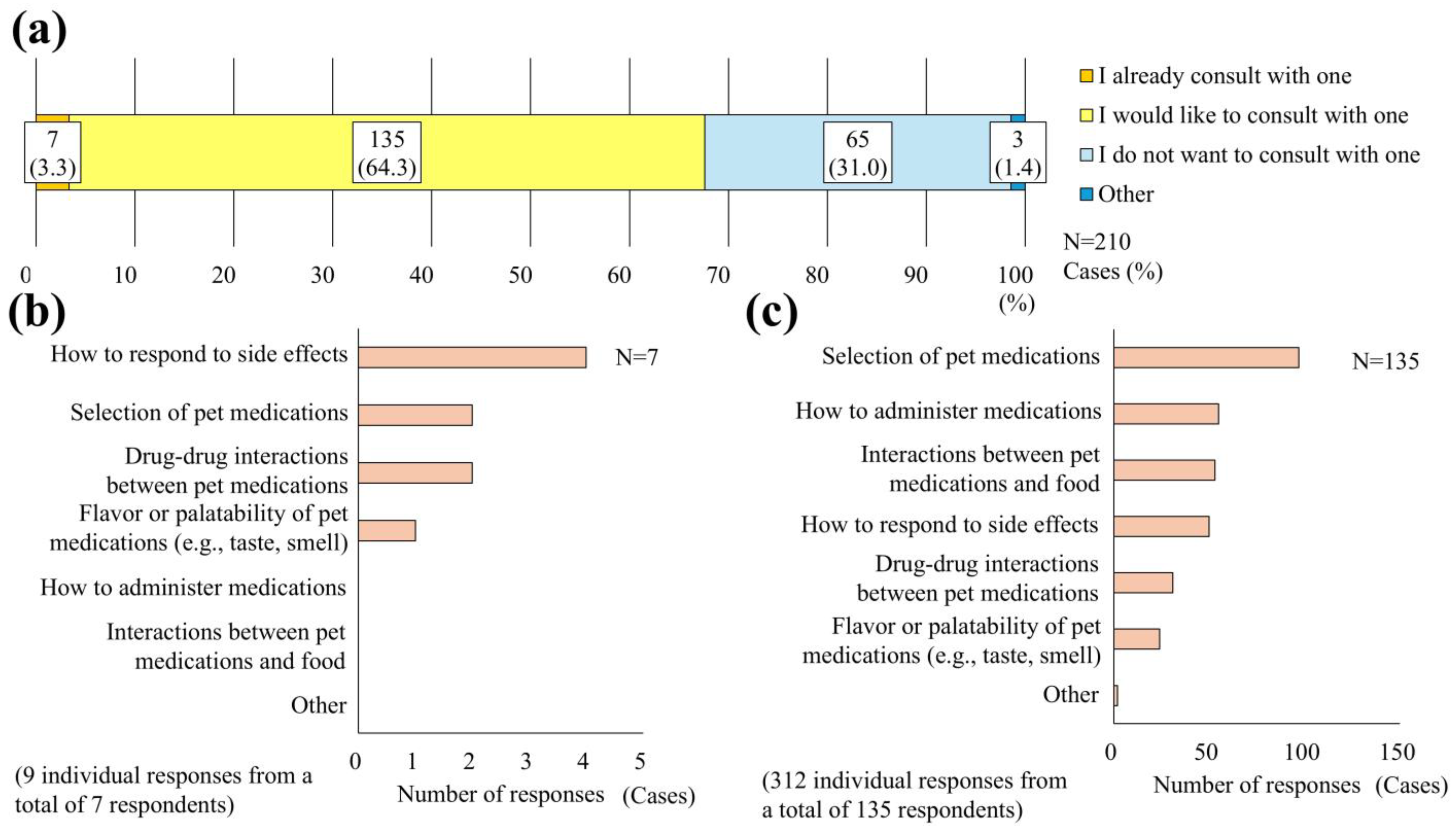

Approximately 65% of pet owners indicated that they would like to consult a pharmacist regarding pet medications, whereas 6.8% reported that they had already done so (Figure 1a). Among those who had consulted or expressed interest in consulting pharmacists, the common topics included drug selection, administration methods, and adverse event management (Figure 1b,c). In species-stratified analyses, 63.0% of dog owners and 64.3% of cat owners expressed willingness to consult a pharmacist, whereas 8.5% and 3.3%, respectively, had already done so (Figure 2a and Figure 3a). The consultation themes were similar between dogs and cats, indicating comparable pharmaceutical care needs across species (Figure 2b,c and Figure 3b,c).

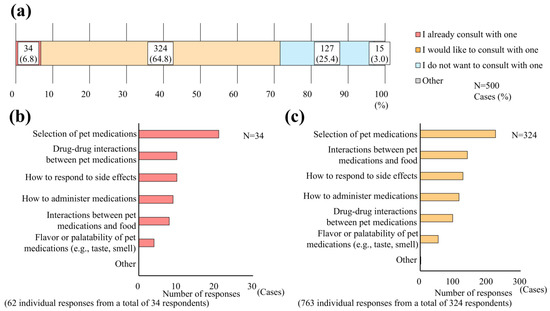

Figure 1.

Pet owners’ willingness to consult pharmacists about pets. (a) Pet owners’ willingness to consult pharmacists regarding pet medications (N = 500). (b) Specific topics consulted about among respondents who had already consulted pharmacists (N = 34). (c) Specific topics of interest among respondents who expressed a willingness to consult pharmacists (N = 324).

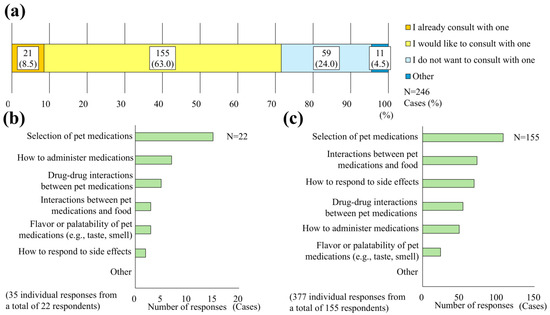

Figure 2.

Willingness of dog owners to consult pharmacists about pets. (a) Willingness of dog owners to consult pharmacists regarding pet medications (N = 246). (b) Specific topics discussed among respondents who had already consulted pharmacists (N = 22). (c) Specific topics of interest among respondents who expressed a willingness to consult pharmacists (N = 155).

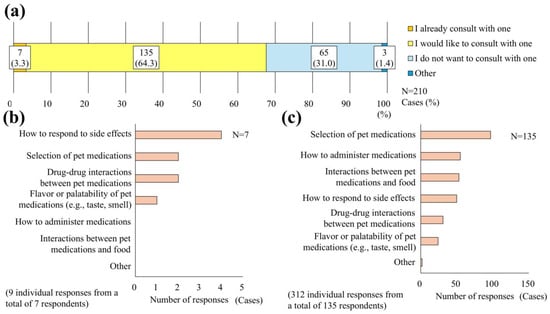

Figure 3.

Willingness of cat owners to consult pharmacists about pets. (a) Willingness of cat owners to consult pharmacists regarding pet medications (N = 210). (b) Specific topics discussed among respondents who had already consulted pharmacists (N = 7). (c) Specific topics of interest among respondents who expressed a willingness to consult pharmacists (N = 135).

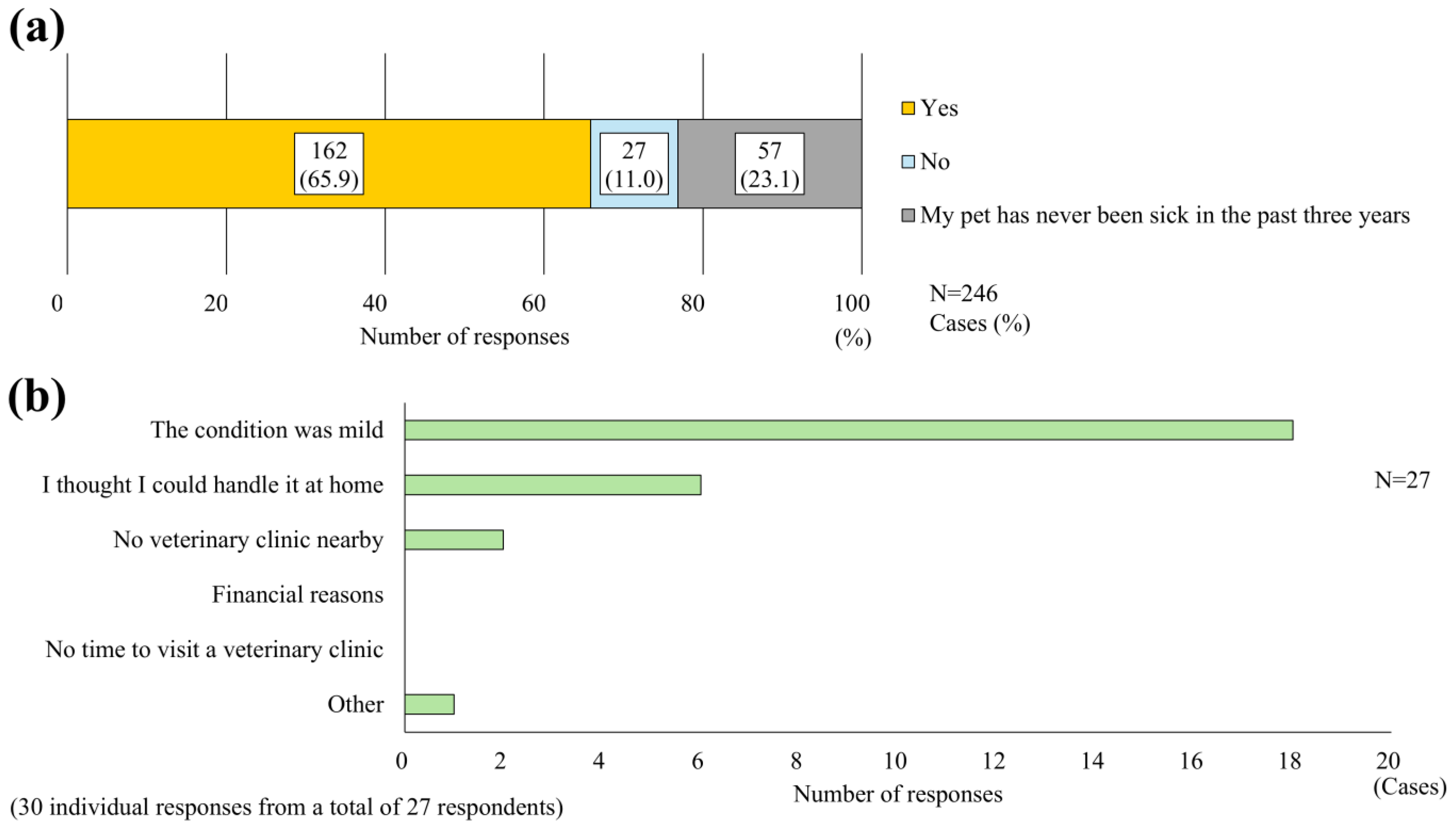

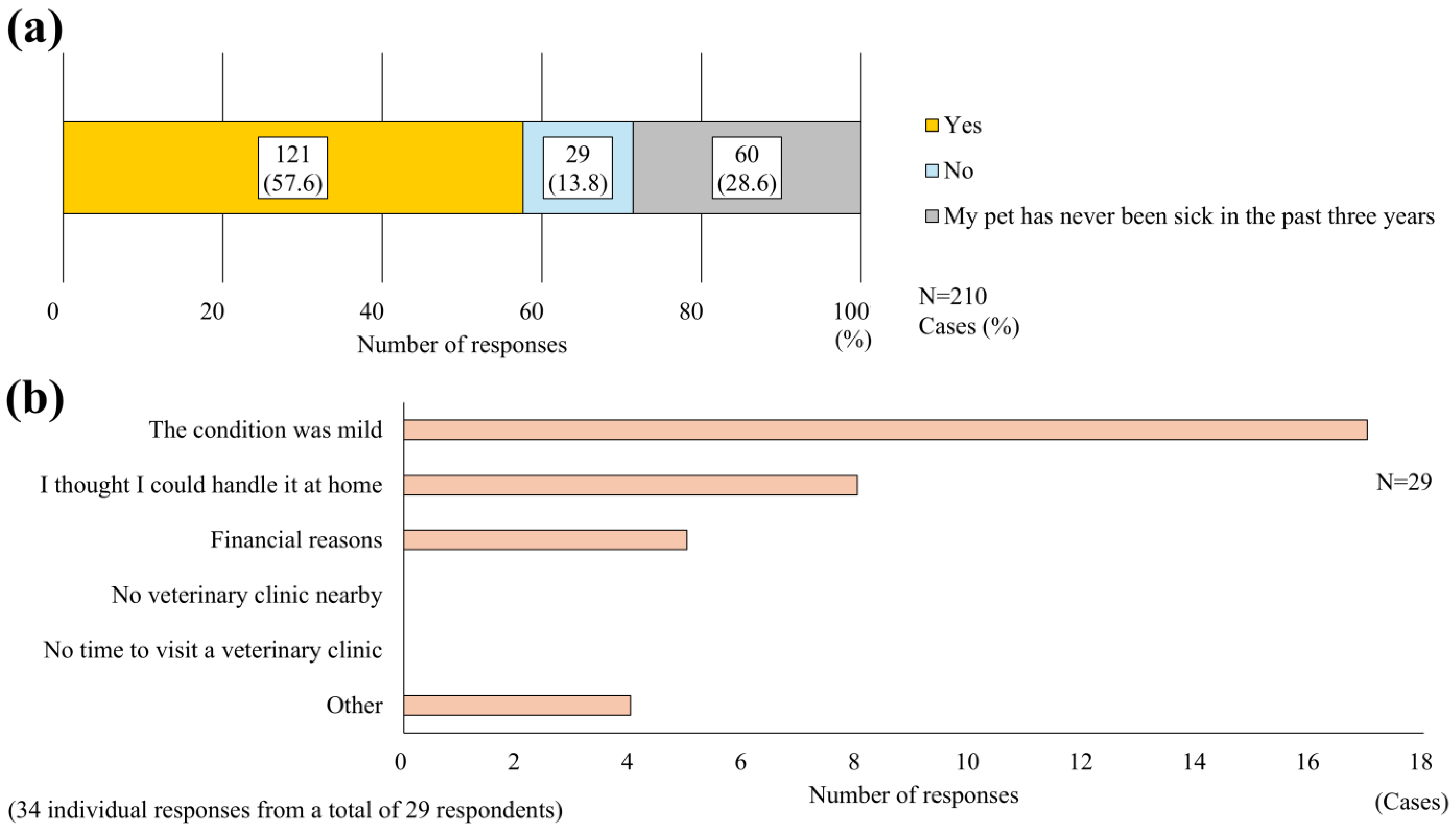

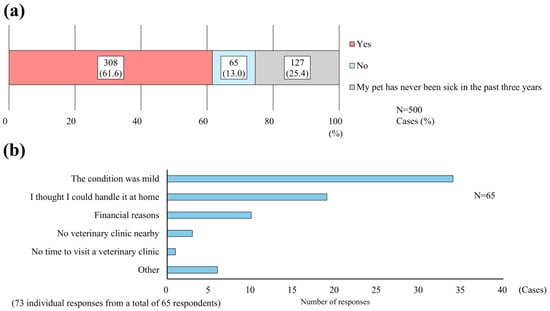

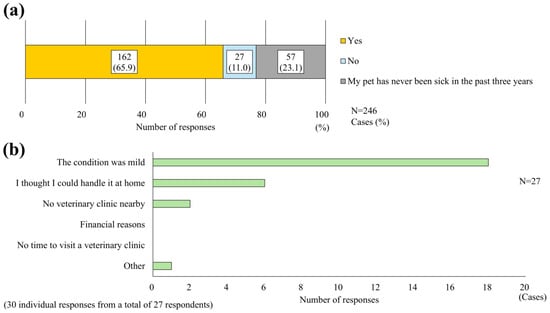

3.3. Veterinary Visit Behavior and Reasons for Non-Visit

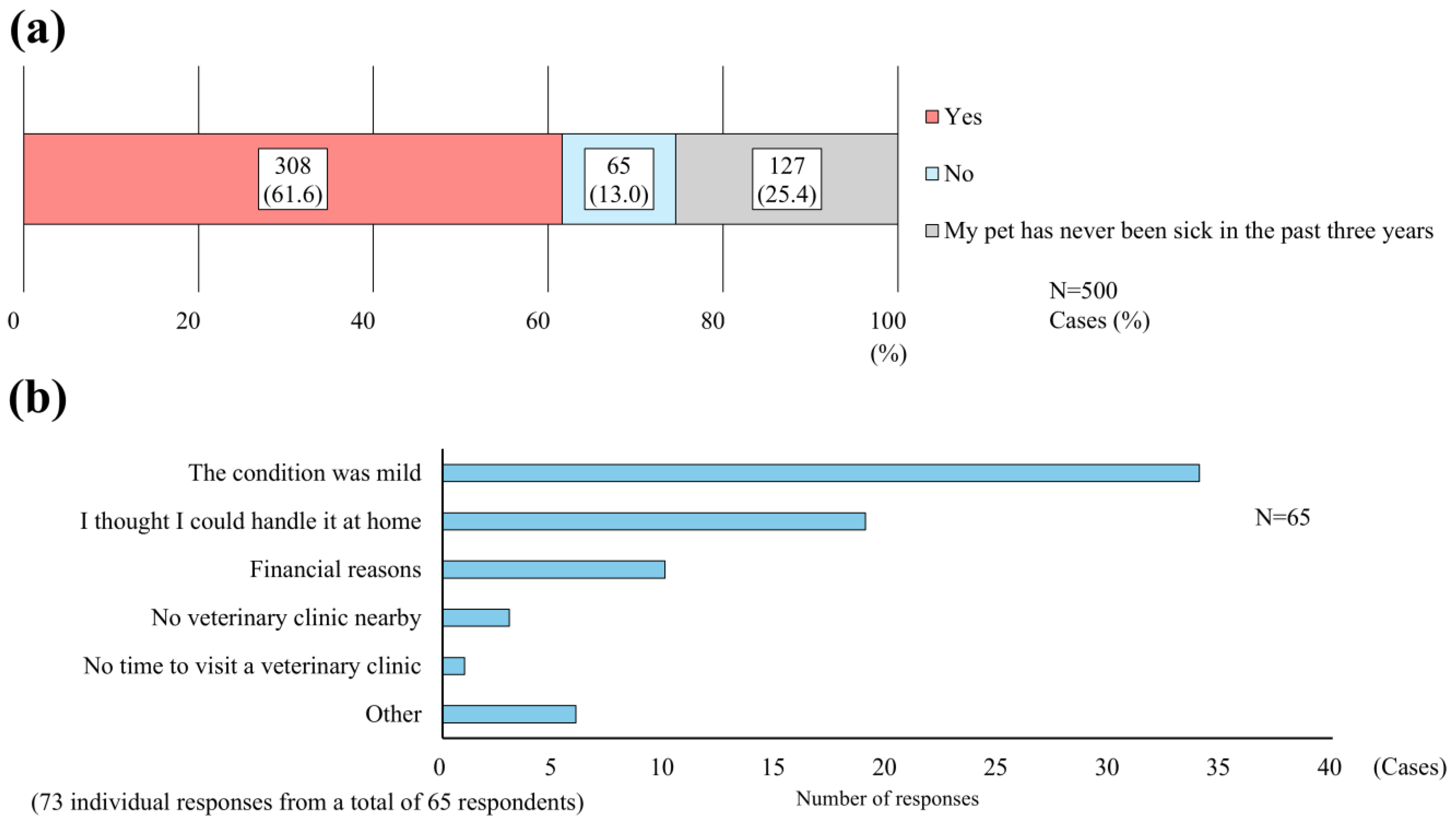

Over the past 3 years, 61.6% of the respondents had taken their pets to veterinary clinics when unwell, while 13.0% had not (Figure 4a). Among those who did not, the primary reasons were mild symptoms, belief in the ability to treat at home, and financial constraints (Figure 4b). Species-stratified analysis showed comparable rates of veterinary visits between dog and cat owners (Figure 5a and Figure 6a). However, the underlying reasons for non-visitation differed, with geographic accessibility being more relevant for dog owners and financial limitations more frequently cited by cat owners (Figure 5b and Figure 6b).

Figure 4.

Veterinary hospital visit behavior and reasons for non-visit. (a) Percentage of pet owners who visited or did not visit a veterinary hospital when their pets were unwell over the past three years (N = 500). (b) Reasons reported by pet owners for not visiting a veterinary hospital despite their pets experiencing health issues (N = 65).

Figure 5.

Veterinary care-seeking behavior among dog owners. (a) Percentage of dog owners who visited or did not visit a veterinary hospital when their dogs were unwell over the past three years (N = 246). (b) Reasons reported by dog owners for not visiting a veterinary hospital despite their dogs experiencing health issues (N = 27).

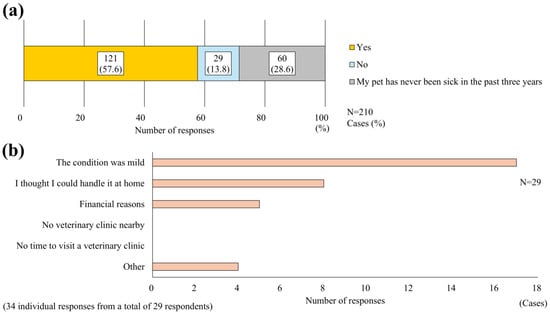

Figure 6.

Veterinary care-seeking behavior among cat owners. (a) Percentage of cat owners who visited or did not visit a veterinary hospital when their cats were unwell over the past three years (N = 210). (b) Reasons reported by cat owners for not visiting a veterinary hospital despite their cats experiencing health issues (N = 29).

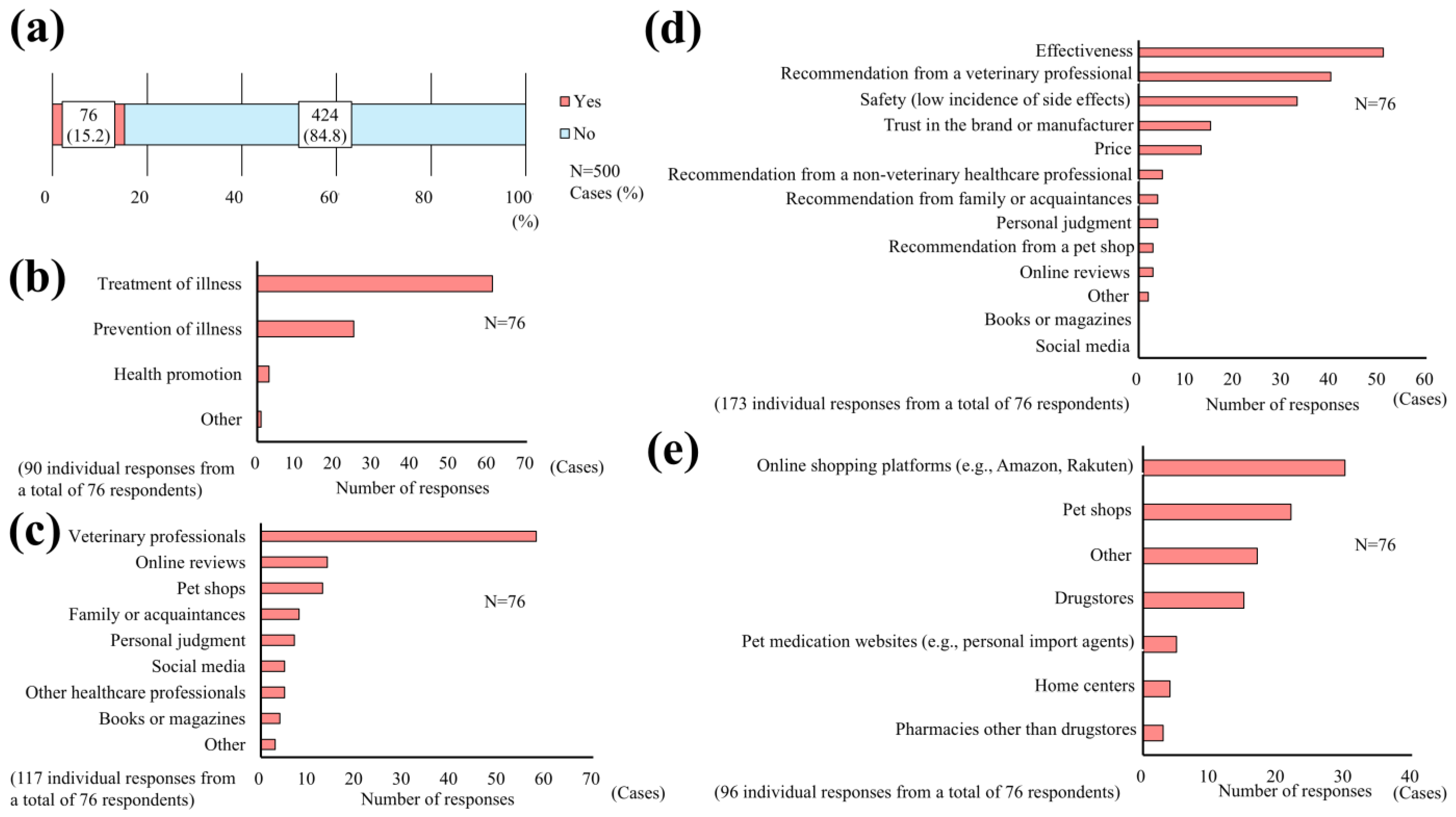

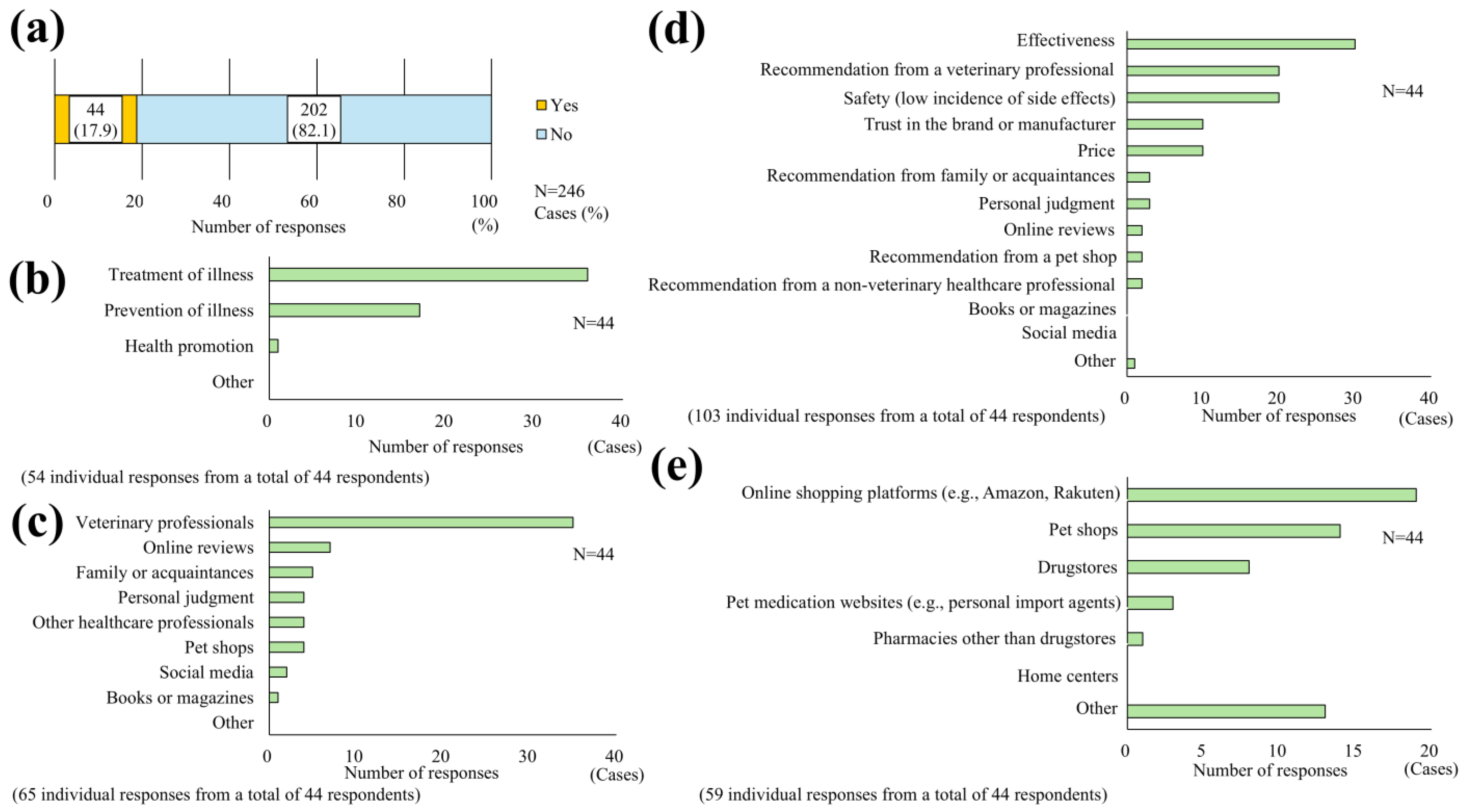

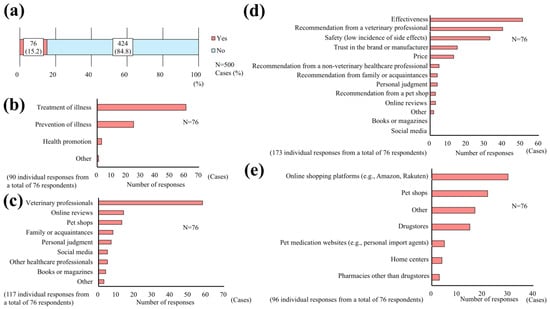

3.4. Use and Purchasing Behavior of OTC Medications for Pets

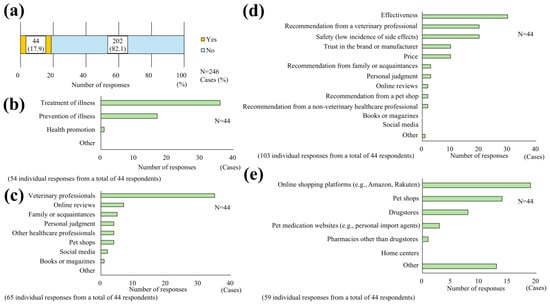

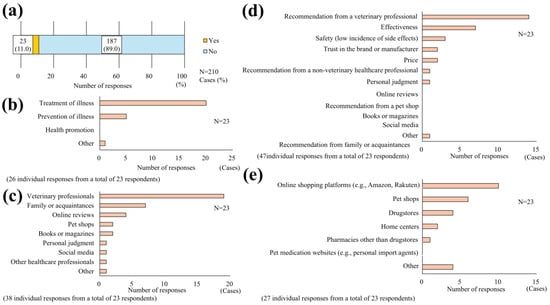

Overall, 15.2% of respondents reported using OTC medications for their pets (Figure 7a). In species-stratified analyses, 17.9% of dog owners and 11.0% of cat owners had used such products (Figure 8a and Figure 9a). These medications were mainly used for disease prevention, treatment, and health maintenance (Figure 7b, Figure 8b and Figure 9b), most commonly involving flea and tick preventives available without veterinary prescriptions in Japan. Pet owners relied on various information sources, such as veterinarians, the Internet, and pet shops when selecting products (Figure 7c, Figure 8c and Figure 9c). Product effectiveness, safety, and recommendations were the key factors influencing this choice (Figure 7d, Figure 8d and Figure 9d). Common purchase locations included drugstores, online platforms, and pet shops (Figure 7e, Figure 8e and Figure 9e).

Figure 7.

Veterinary hospital visit behavior and reasons for non-visit. (a) Percentage of pet owners who have used OTC medications for their pets (N = 500). (b) Purpose of OTC medication use among respondents who reported OTC use (N = 76). (c) Sources of information utilized by pet owners when purchasing OTC medications (N = 76). (d) Factors influencing the selection of OTC pet medications (N = 76). (e) Preferred purchasing locations for OTC pet medications (N = 76).

Figure 8.

Veterinary care-seeking behavior among dog owners. (a) Percentage of dog owners who have used OTC medications for their dogs (N = 246). (b) Purpose of OTC medication use among respondents who reported OTC use (N = 44). (c) Sources of information used by dog owners when purchasing OTC medications (N = 44). (d) Factors influencing the selection of OTC pet medications (N = 44). (e) Preferred purchasing locations for OTC pet medications (N = 44). Note: In Japan, “pharmacies” are licensed dispensaries operated by pharmacists, whereas “drugstores” are outlets that sell OTC medicines and daily goods, and pharmacist consultation may not always be available.

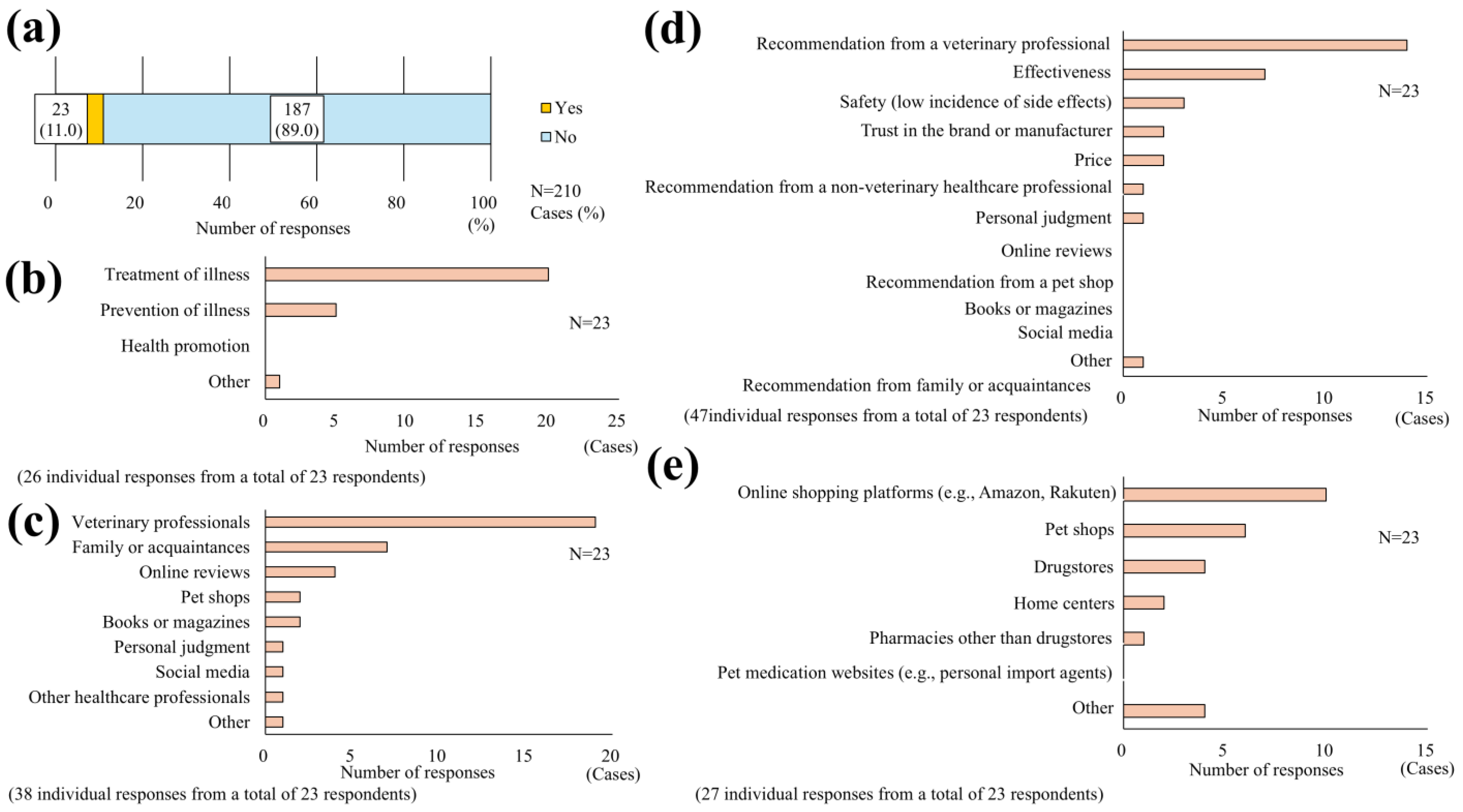

Figure 9.

Veterinary care-seeking behavior among cat owners. (a) Percentage of cat owners who have used OTC medications for their cats (N = 210). (b) Purpose of OTC medication use among respondents who reported OTC use (N = 23). (c) Sources of information used by cat owners when purchasing OTC medications (N = 23). (d) Factors influencing the selection of OTC pet medications (N = 23). (e) Preferred purchasing locations for OTC pet medications (N = 23). Note: In Japan, “pharmacies” are licensed dispensaries operated by pharmacists, whereas “drugstores” are outlets that sell OTC medicines and daily goods, and pharmacist consultation may not always be available.

3.5. Monthly Expenditure on OTC Pet Medications

Among those who reported using OTC pet medications, most spent less than 3000 yen per month, with 44.7% spending less than 3000 yen and 32.9% spending between 3000 and 5000 yen (Table 2). In the species-stratified analyses, both dog and cat owners showed similar spending trends, with the majority in each group reporting monthly expenditures below 5000 yen (Table 3 and Table 4).

Table 2.

Monthly Expenditure on OTC Pet Medications.

Table 3.

Monthly Expenditure on OTC Pet Medications for dogs.

Table 4.

Monthly Expenditure on OTC Pet Medications for cats.

4. Discussion

This study provides the first comprehensive description of Japanese pet owners’ self-medication practices and OTC drug use in companion animals.

By synthesizing owner-reported behaviors, purchasing patterns, and attitudes toward pharmacy support, this study identified actionable community-based strategies to strengthen rational pet self-medication.

The findings suggest a possible gap between owners’ demand and current access to pharmacist consultations. Many owners wish to consult pharmacists about pet medicines, yet only a small fraction have done so. In recent years, a small number of pet specialty pharmacies that accept prescriptions from veterinary hospitals and provide both medication dispensing and compounding/sterile preparation of complex formulations, such as antineoplastic drugs, have emerged in Japan [9,10,11]. Compared with more than 60,000 human pharmacies serving ~120 million people in Japan [12], the small number of pet-specialty pharmacies providing veterinary dispensing covers only a very small portion of the potential need across ~6.8 million dogs and ~9.2 million cats [13]. To efficiently meet latent demand, Japan should implement initiatives to expand or better leverage pet specialty pharmacies and formalize their linkages with community pharmacies (e.g., recommendations of veterinarian consultation for owners, shared protocols, and tele pharmacy support). This means that owners can obtain brief, standardized advice without substituting veterinary diagnosis and care.

Owners prioritize effectiveness and safety but often rely on heterogeneous, non-professional sources. Our findings highlight substantial gaps in owners’ knowledge that may contribute to medication errors and misuse. This observation is consistent with previous reports of inappropriate medication handling by pet owners [5]. Pharmacist-led counseling that raises owners’ pharmaceutical literacy is essential for rational self-medication. Concise point-of-purchase counseling (dosing basics, “do-not-use” human drugs, and clear referral triggers when symptoms persist or worsen) delivered by pharmacists can improve decision quality. Internationally, community pharmacists in the United States and several European countries routinely dispense veterinary prescriptions and provide medication counseling under clearly defined regulatory frameworks [3,4,14]. In these settings, collaboration between pharmacists and veterinarians has been facilitated by established educational pathways and the separation of veterinary medical practice from drug dispensation, allowing pharmacists to handle veterinary prescriptions. In contrast, Japan’s veterinary pharmaceutical system is still largely veterinarian-centered, and OTC products for companion animals are limited in number and scope. These contextual differences highlight the need to develop Japan-specific frameworks for pharmacist participation that align with existing veterinary practice structures and regulatory systems.

Providing species-specific advice will require specialized veterinary training and clear communication channels between pharmacists and veterinarians. The scope, responsibilities, and standards for this training are still under active discussion globally [4,14]. Recent work by Davidson and colleagues has emphasized the need for structured-based curricula in veterinary pharmacy and the establishment of defined professional standards for pharmacists involved in animal care [15]. Japan has begun moving in this direction. For example, a university-led initiative is developing an e-learning pharmacy curriculum for veterinary care, signaling the groundwork for structured preparation [16]. Building on animal pathophysiology and the realities of veterinary practice, pharmacists need a translational skill set that adapts human therapeutics to animal patients, recognizing where human norms align and where species differences render them unsafe or inapplicable. Therefore, co-creating an integrated veterinary pharmacy field jointly shaped by veterinarians and pharmacists remains essential. A practical next step is to develop a certification program for veterinary pharmacists that establishes minimum competency standards for counseling and referral, aligns with international discussions on roles and skills [4,14], and enhances the trustworthiness and reliability of pharmacist-provided guidance in daily OTC contexts.

The modest OTC spending in this survey suggests its use is mainly for minor/preventive needs. The species-stratified results indicated broadly similar spending patterns between dog and cat owners, suggesting that economic considerations may influence pet self-medication behavior across species rather than being species-specific. The overall modest expenditures observed in both groups imply that pet owners tend to limit OTC use to minor or preventive purposes, likely reflecting a combination of economic caution and limited access to veterinary or pharmaceutical guidance. Previous studies have suggested that many Japanese pet owners, particularly those caring for rescued or adopted animals, manage healthcare costs conservatively, which may contribute to uniformly low spending levels [17]. Therefore, pharmacy-based interventions should focus on providing affordable, accessible counseling and promoting appropriate product selection, regardless of pet species. Accordingly, low-cost, scalable pharmacy interventions (standardized counseling, clearer package insert interpretation, and simple documentation/feedback to clinics) are well matched to owner expectations. By improving decision quality at the point of purchase and reducing inappropriate use or delayed referral, these actions advance rational self-medication and contribute to the One Health agenda—including antimicrobial stewardship—by promoting safer medication practices that benefit animal and human health alike [18].

This study has several limitations. First, as this was an online panel survey, respondents interested in pet OTC use may have been more likely to participate, introducing a potential selection bias. Second, this survey targeted only dog and cat owners; however, national surveys indicate that other companion species, such as ornamental fish, birds, rabbits, small rodents, and reptiles, are also common in Japan, limiting generalizability beyond dogs and cats [13]. Nevertheless, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first large-scale owner-centered survey on pet OTC use in Japan. The findings provide important insights into owners’ behaviors and highlight the need for stronger collaboration between pharmacists and veterinarians. Such cooperation is essential to ensure medication safety, reduce misuse, and support owners lacking access to professional guidance at the point of purchase. Future research should evaluate the outcomes of pharmacist interventions and targeted owner education in real-world pharmacy and veterinary settings. Policy initiatives that clarify and promote pharmacists’ roles in veterinary pharmaceutical care may be warranted to meet the growing needs of Japanese society.

5. Conclusions

The findings of this study indicate that Japanese pet owners show a strong interest in pharmacist support, use OTCs mainly for minor/preventive needs with modest spending, and prioritize effectiveness and safety, revealing a gap in expert guidance at the point of purchase. Emerging pet specialty pharmacies are well-positioned as first-contact hubs to deliver brief, standardized counseling without replacing veterinary care. Implementing this pharmacy-led first-contact model will require veterinary-specific training and establishing formal credentials for veterinary pharmacists, together with clear pharmacist–veterinarian communication, to promote rational self-medication and safer use consistent with one’s health.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/pets2040039/s1, Supplementary Questionnaire S1: SQ1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.K., D.K., H.S., H.N. and Y.M.; methodology, T.K., D.K., H.S., H.N. and Y.M.; analysis, T.K. and D.K., writing—original draft preparation, T.K., D.K., H.S., Y.N., S.K., H.N. and Y.M.; writing—review and editing, T.K., D.K., H.S., Y.N., S.K., H.N. and Y.M.; visualization, T.K., D.K. and Y.M.; supervision, T.K. and Y.M.; project administration, T.K., D.K., Y.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Tohoku Medical and Pharmaceutical University (protocol code: 2025-A-002-0000; date of approval: 28 May 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

All respondents provided informed consent online to participate in the questionnaire webpage.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article and Supplementary Materials.

Acknowledgments

We express our heartfelt gratitude to the pet owners who participated in the survey for their invaluable cooperation. We also express our sincere gratitude to Yu Takayama, who supported the implementation of this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sueda, K.L.C.; Hart, B.L.; Cliff, K.D. Characterisation of plant eating in dogs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2008, 111, 120–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pons-Hernandez, M.; Wyatt, T.; Hall, A. Investigating the illicit market in veterinary medicines: An exploratory online study with pet owners in the United Kingdom. Trends Organ. Crim. 2023, 26, 308–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nichelason, A.E.; Williams, S.R.; Pinto, A.; Bean, I. Convenience and price drive online pharmacy usage by veterinary clients. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2024, 262, 1511–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fredrickson, M.E.; Terlizzi, H.; Horne, R.L.; Dannemiller, S. The role of the community pharmacist in veterinary patient care: A cross-sectional study of pharmacist and veterinarian viewpoints. Pharm. Pract. 2020, 18, 1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, D.D.; Scallan Walter, E.J. Colorado pet owners’ perceptions of and attitudes towards antimicrobial drug use and resistance. Vet. Rec. 2023, 192, e2583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDaniel, M.; Glazier, E.; Truong, N.; Marsh, L.; Cahill, N.; Essel, L.B.; Melton, B.L.; Meyer, E.G. Veterinary prescription errors in a community pharmacy setting: A retrospective review. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2022, 62, 512–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konno, T.; Suzuki, H.; Suzuki, N.; Okada, K.; Nishikawa, Y.; Kikuchi, D.; Nakamura, H.; Murai, Y. Current situation for pharmacists in Japanese veterinary medicine: Exploring the pharmaceutical needs and challenges of veterinary staff to facilitate collaborative veterinary care. Pharmacy 2024, 12, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konno, T.; Suzuki, H.; Kikuchi, D.; Nishikawa, Y.; Kisara, S.; Nakamura, H.; Murai, Y. Future perspectives on household pharmaceutical management and medication administration for companion animals in Japan. Pharm. Pract. 2025; In press. [Google Scholar]

- Pharmacy Co., Ltd. 12 Pharmacy: Dispensing-Separation Model Dedicated to Animal Hospitals. Available online: https://12pharmacy.co.jp/ (accessed on 1 September 2025). (In Japanese).

- Cygni Inc. Cygni: E-Commerce Platform for Veterinary Clinics. Available online: https://vet.cygni.co.jp/disp/CPWIncludeWide_vet.jsp?dispNo=006102001001 (accessed on 1 September 2025). (In Japanese).

- Pet-Yaku. Pet-Yaku: Online Information and Supply for Pet Medicines. Available online: https://www.pet-yaku.com/ (accessed on 1 September 2025). (In Japanese).

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Annual Report of Public Health Administration and Services (FY2023), Results Summary—4. Pharmaceutical Affairs. 2024. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/eisei_houkoku/23/dl/kekka4.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025). (In Japanese).

- Japan Pet Food Association (JPFA). National Dog and Cat Ownership Survey: Key Indicators Summary 2024. Available online: https://petfood.or.jp/pdf/data/2024/3.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2025). (In Japanese).

- Kovačević, Z.; Mijač, J.; Ružić-Muslić, D.; Ćupić, T. Exploring pet owners’ attitudes toward compounded and human-approved medicines: A questionnaire-based pilot study. Vet. Res. Commun. 2025, 49, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidson, G. Veterinary Compounding: Regulation, Challenges, and Resources. Pharmaceutics 2017, 9, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tokyo University of Pharmacy and Life Sciences. Initiative To Develop an Educational Program for Pharmacists Engaged in Veterinary Medicine. 2025. Available online: https://www.toyaku.ac.jp/pharmacy/newstopics/2025/0626_6783.html (accessed on 1 September 2025). (In Japanese).

- Rand, J.; Morton, J.M.; Dias, R. Situational analysis of cat ownership and cat caring: Exploring the diversity of cat management practices and their welfare implications. Animals 2024, 14, 2849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Destoumieux-Garzón, D.; Mavingui, P.; Boetsch, G.; Boissier, J.; Darriet, F.; Duboz, P.; Fritsch, C.; Giraudoux, P.; Le Roux, F.; Morand, S.; et al. The one health concept: 10 years old and a long road ahead. Front. Vet. Sci. 2018, 5, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).