High Prevalence of Vaginal Candidiasis and Absence of Trichomonas vaginalis Among Female Patients in Da Nang, Vietnam

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Ethics Issues and Sample Population

2.2. Participant Recruitment

2.3. Microbiology Laboratory Assessment and Data Collection

- A grayish-white, thin, and homogeneous vaginal discharge;

- A vaginal pH exceeding 4.5;

- A fishy or amine odor following the addition of 10% KOH;

- The presence of clue cells (greater than 20%) observed under microscopic examination.

2.4. Statistics Analysis

3. Results

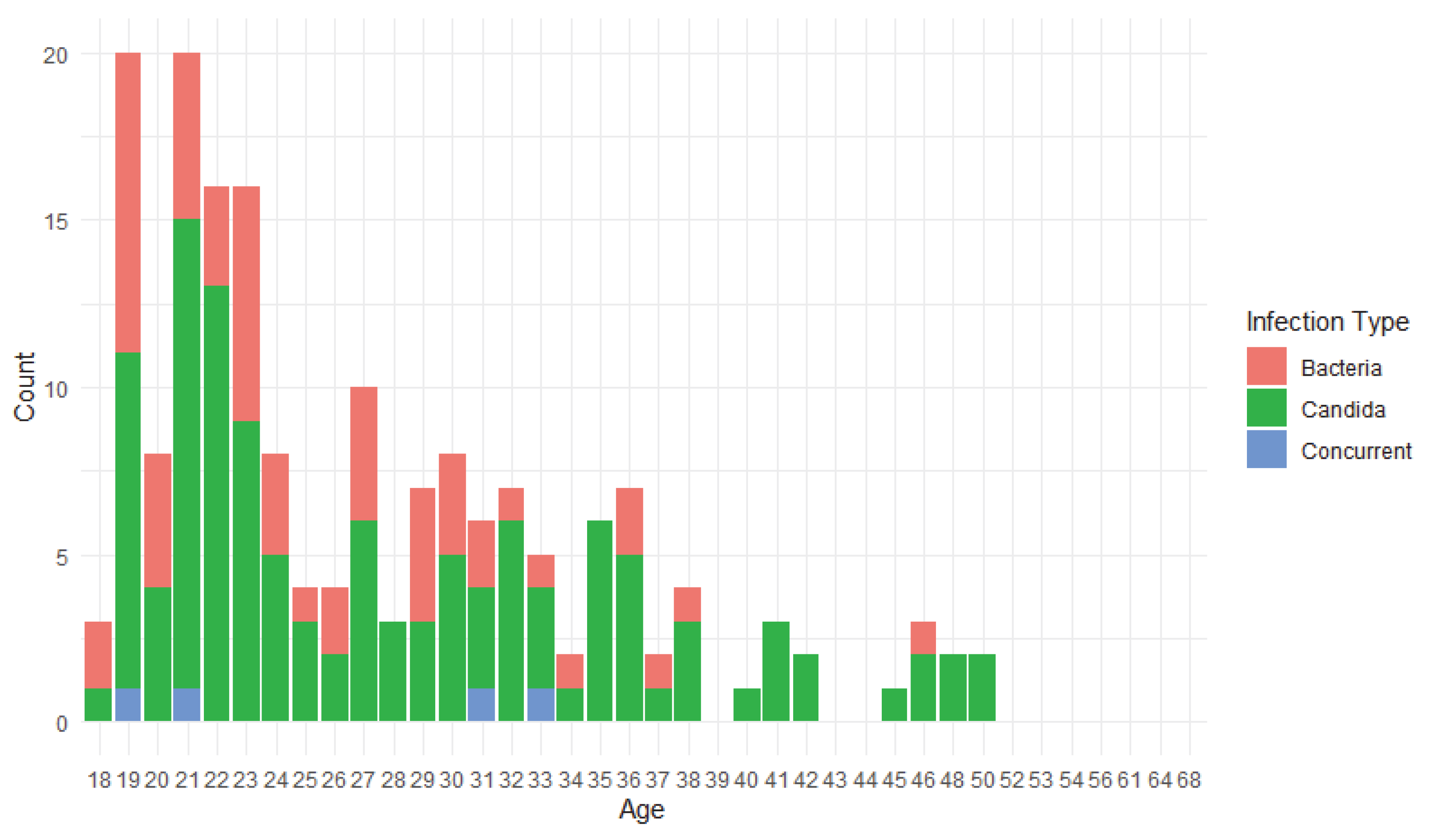

3.1. Demographic Data

3.2. Prevalence of Vaginitis and Risk Factors’ Analysis

3.3. Comparison of the Amsel and Nugent Score for Vaginitis Diagnosis

4. Discussion

4.1. Prevalence of Vaginitis and Its Causal Pathogen in the Cohort

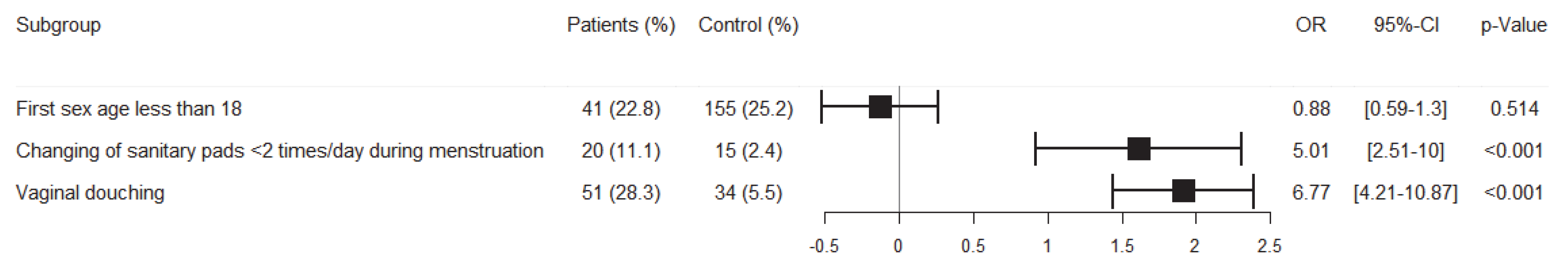

4.2. Risk Factors of Vaginitis in the Cohort

4.3. Comparison of Nugent and Amsel’s Methods in Vaginitis Diagnosis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ASEAN | The Association of Southeast Asian Nations |

| BV | Bacterial vaginosis |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| CV | Candidal vaginitis |

| NPV | Negative predictive value |

| OR | Odds ratio |

| PPV | Positive predictive value |

| STIs | Sexually transmitted infections |

| VVC | Vulvovaginal candidiasis |

| TV | Trichomoniasis vaginitis |

References

- Zapata, M.R. Diagnosis and treatment of Vulvovaginitis. In Handbook of Gynecology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 297–317. [Google Scholar]

- Kalia, N.; Singh, J.; Kaur, M. Microbiota in vaginal health and pathogenesis of recurrent vulvovaginal infections: A critical review. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2020, 19, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Rolfs, J. Common Infections Encountered in Obstetrics/Gynecology. Physician Assist. Clin. 2022, 7, 419–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildebrand, J.P.; Carlson, K.; Kansagor, A.T. Vaginitis. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Peebles, K.; Velloza, J.; Balkus, J.E.; McClelland, R.S.; Barnabas, R.V. High Global Burden and Costs of Bacterial Vaginosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sex. Transm. Dis. 2019, 46, 304–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denning, D.W.; Kneale, M.; Sobel, J.D.; Rautemaa-Richardson, R. Global burden of recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis: A systematic review. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, e339–e347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bautista, C.T.; Wurapa, E.; Sateren, W.B.; Morris, S.; Hollingsworth, B.; Sanchez, J.L. Bacterial vaginosis: A synthesis of the literature on etiology, prevalence, risk factors, and relationship with chlamydia and gonorrhea infections. Mil. Med. Res. 2016, 3, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcon, R.M.G.; Alcazar, R.M.U.; Guda, J.V.; Tantengco, O.A.G. A systematic review and metaanalysis on the prevalence of vulvovaginal candidiasis in Southeast Asian countries. SciEnggJ 2024, 17, 341–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Alfouzan, W. Candida auris: Epidemiology, diagnosis, pathogenesis, antifungal susceptibility, and infection control measures to combat the spread of infections in healthcare facilities. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, M.C.; Alastruey-Izquierdo, A.; Berman, J.; Bicanic, T.; Bignell, E.M.; Bowyer, P.; Bromley, M.; Brüggemann, R.; Garber, G.; Cornely, O.A. Tackling the emerging threat of antifungal resistance to human health. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2022, 20, 557–571. [Google Scholar]

- ADB. Asian Economic Integration Report 2024, Decarbonizing Global Value Chains; Asian Development Bank: Manila, Philippines, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Morsli, M.; Gimenez, E.; Magnan, C.; Salipante, F.; Huberlant, S.; Letouzey, V.; Lavigne, J.-P. The association between lifestyle factors and the composition of the vaginal microbiota: A review. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2024, 43, 1869–1881. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Guidelines For the Management of Symptomatic Sexually Transmitted Infections; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021.

- van Schalkwyk, J.; Yudin, M.H.; Infectious Disease, C. Vulvovaginitis: Screening for and management of trichomoniasis, vulvovaginal candidiasis, and bacterial vaginosis. J. Obs. Gynaecol. Can. 2015, 37, 266–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, H.; Drexler, M. Improving the Diagnosis of Vulvovaginitis: Perspectives to Align Practice, Guidelines, and Awareness. Popul. Health Manag. 2020, 23, S3–S12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vieira-Baptista, P.; Stockdale, C.K.; Sobel, J. International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease Recommendations for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Vaginitis; Ad Médic, Lda.: Lisbon, Portugal, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Amsel, R.; Totten, P.A.; Spiegel, C.A.; Chen, K.C.; Eschenbach, D.; Holmes, K.K. Nonspecific vaginitis. Diagnostic criteria and microbial and epidemiologic associations. Am. J. Med. 1983, 74, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nugent, R.P.; Krohn, M.A.; Hillier, S.L. Reliability of diagnosing bacterial vaginosis is improved by a standardized method of Gram stain interpretation. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1991, 29, 297–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, A.T.C.; Nguyen, N.T.; Tran, T.T.; Nguyen, T.T.; Hoang, T.T.; Tran, L.M.; Tran, K.T.; Phan, T.D.; Nguyen, X.T.; Le, T.M.; et al. Prevalence and associated factors of bacterial vaginosis among pregnant women in Hue, Vietnam. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2024, 18, 925–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trang, V.T.M.; Linh, D.T.T. Prevalence of vaginitis of reproductive women visiting the polyclinic of Pham Ngoc Thach University of Medicine from 10/2022 to 3/2023. Vietnam. Med. J. 2024, 534, 246–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linh, D.M.; Tam, H.T.T.; Linh, N.T.T. Reseach the prevalence of vaginitis in married woman in Can Tho Central general Hospital and Can Tho Obstetrics and Gynecology hospital. Can. Tho J. Med. Pharm. 2020, 27, 53–59. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, S.H.; Hsu, H.C.; Lee, T.F.; Fan, H.M.; Tseng, C.W.; Chen, I.H.; Shen, H.; Lee, C.Y.; Tai, H.T.; Hsu, H.M.; et al. Prevalence, Associated Factors, and Appropriateness of Empirical Treatment of Trichomoniasis, Bacterial Vaginosis, and Vulvovaginal Candidiasis among Women with Vaginitis. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e0016123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.; Wu, Y.; Li, Y.; Hu, X.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, Y. Retrospective study of pathogens involved in vaginitis among Chinese women. BMC Womens Health 2023, 23, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oparaugo, C.T.; Iwalokun, B.A.; Nwaokorie, F.O.; Okunloye, N.A.; Adesesan, A.A.; Edu-Muyideen, I.O.; Adedeji, A.M.; Ezechi, O.C.; Deji-Agboola, M.A. Occurrence and Clinical Characteristics of Vaginitis among Women of Reproductive Age in Lagos, Nigeria. Adv. Reprod. Sci. 2022, 10, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Aziz, M.; Mahdy, M.A.K.; Abdul-Ghani, R.; Alhilali, N.A.; Al-Mujahed, L.K.A.; Alabsi, S.A.; Al-Shawish, F.A.M.; Alsarari, N.J.M.; Bamashmos, W.; Abdulwali, S.J.H.; et al. Bacterial vaginosis, vulvovaginal candidiasis and trichomonal vaginitis among reproductive-aged women seeking primary healthcare in Sana’a city, Yemen. BMC Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.T.; Nguyen, T.T.; Nguyen, N.D.; Nguyen, H.H.; Hoang, H.T.; Bui, L.T.; Nguyen, M.V.; Dang, C.P.; Cao, V. Sexually Transmitted Diseases and Their Associated Factors in a Cohort in Da Nang City: An Alarming Trend in Syphilis Rates and Infection at Young Ages. Acta Microbiol. Hell. 2025, 70, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, B.E.; Chen, H.Y.; Wang, Q.J.; Zariffard, M.R.; Cohen, M.H.; Spear, G.T. Utility of Amsel criteria, Nugent score, and quantitative PCR for Gardnerella vaginalis, Mycoplasma hominis, and Lactobacillus spp. for diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis in human immunodeficiency virus-infected women. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2005, 43, 4607–4612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Udayalaxmi; Bhat, G.; Kotigadde, S.; Shenoy, S. Comparison of the Methods of Diagnosis of Bacterial Vaginosis. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2011, 5, 498–501. [Google Scholar]

- Bhujel, R.; Mishra, S.K.; Yadav, S.K.; Bista, K.D.; Parajuli, K. Comparative study of Amsel’s criteria and Nugent scoring for diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis in a tertiary care hospital, Nepal. BMC Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengistie, Z.; Woldeamanuel, Y.; Asrat, D.; Yigeremu, M. Comparison of clinical and Gram stain diagnosis methods of bacterial vaginosis among pregnant women in Ethiopia. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2013, 7, 2701–2703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Categories | Group | No (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age groups | 18–30 | 574 (72.1%) |

| 31–50 | 205 (25.8%) | |

| >50 | 17 (2.1%) | |

| Education | High school and lower | 83 (10.4%) |

| University, college | 629 (79.0%) | |

| Post-graduate | 84 (10.6%) | |

| Occupation | Officer | 9 (1.1%) |

| Industrial worker | 36 (4.5%) | |

| Businessman, housework | 101 (12.7%) | |

| Others | 650 (81.7%) | |

| Residence | Urban | 584 (73.4%) |

| Rural | 192 (24.1%) | |

| Others | 20 (2.5%) | |

| Marriage | Married | 477 (59.9%) |

| Single/Divorced | 319 (41.1%) |

| Group | Number | Percentage (%) [95%CI] |

|---|---|---|

| Nonvaginitis | 616 | 77.4 [74.5; 80.3] |

| Vaginitis | 180 | 22.6 [19.7; 25.5] |

| BV | 57 | 31.67 [24.8; 38.5] |

| VVC | 119 | 66.11 [59.1; 73.1] |

| TV | 0 | 0.0 [0; 1.67] |

| Concurrent (BV and CV) | 4 | 2.22 [0.1; 4.4] |

| Physical Issues | Vaginitis Patients | Percent (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical symptoms | No symptom | 20 | 11.1 | |

| Itchy | 82 | 45.6 | ||

| Irritant (stinging, burning sensation) | 62 | 34.4 | ||

| Others (dyspareunia, lower abdominal pain, and painful urination) | 16 | 8.9 | ||

| Vulvovaginal abnormalities (erythema, edema, and/or fissures) | Yes | 101 | 56.1 | |

| No | 79 | 43.9 | ||

| Vaginal discharge | Volume | High volume | 60 | 33.3 |

| Average volume | 76 | 42.2 | ||

| Low volume | 44 | 24.4 | ||

| Fishy odor | Yes | 50 | 27.8 | |

| No | 130 | 72.2 | ||

| Color | Yellow | 56 | 31.1 | |

| Green | 60 | 33.3 | ||

| White (normal) | 64 | 35.6 | ||

| Viscosity | Normal | 1 | 0.6 | |

| Dilute | 104 | 57.8 | ||

| Thick | 75 | 41.7 | ||

| pH | ≥4.5 | 60 | 33.3 | |

| <4.5 | 120 | 66.7 | ||

| Method of Diagnosis | Nugent’s Criteria | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | Total | ||||||

| Amsel’s criteria | Positive | 54 | 7 | 61 (7.7%) | 98.2 | 99.1 | 88.5 | 99.9 |

| Negative | 1 | 734 | 735 (92.3%) | |||||

| Total | 55 (6.9%) | 741 (93.1%) | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Hellenic Society for Microbiology. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Le, V.X.; Nguyen, K.T.; Nguyen, M.V.; Ho, T.T.; Tran, T.T.; Dang, C.P.; Cao, V.; Le, T.T. High Prevalence of Vaginal Candidiasis and Absence of Trichomonas vaginalis Among Female Patients in Da Nang, Vietnam. Acta Microbiol. Hell. 2025, 70, 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/amh70030026

Le VX, Nguyen KT, Nguyen MV, Ho TT, Tran TT, Dang CP, Cao V, Le TT. High Prevalence of Vaginal Candidiasis and Absence of Trichomonas vaginalis Among Female Patients in Da Nang, Vietnam. Acta Microbiologica Hellenica. 2025; 70(3):26. https://doi.org/10.3390/amh70030026

Chicago/Turabian StyleLe, Vinh Xuan, Kieu Thi Nguyen, Minh Van Nguyen, Tram ThiHoang Ho, Tuyen ThiThanh Tran, Cong Phi Dang, Van Cao, and Thuy Thi Le. 2025. "High Prevalence of Vaginal Candidiasis and Absence of Trichomonas vaginalis Among Female Patients in Da Nang, Vietnam" Acta Microbiologica Hellenica 70, no. 3: 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/amh70030026

APA StyleLe, V. X., Nguyen, K. T., Nguyen, M. V., Ho, T. T., Tran, T. T., Dang, C. P., Cao, V., & Le, T. T. (2025). High Prevalence of Vaginal Candidiasis and Absence of Trichomonas vaginalis Among Female Patients in Da Nang, Vietnam. Acta Microbiologica Hellenica, 70(3), 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/amh70030026