Optimisation of Ex Vivo Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cell Culture and DNA Double Strand Break Repair Kinetics

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents

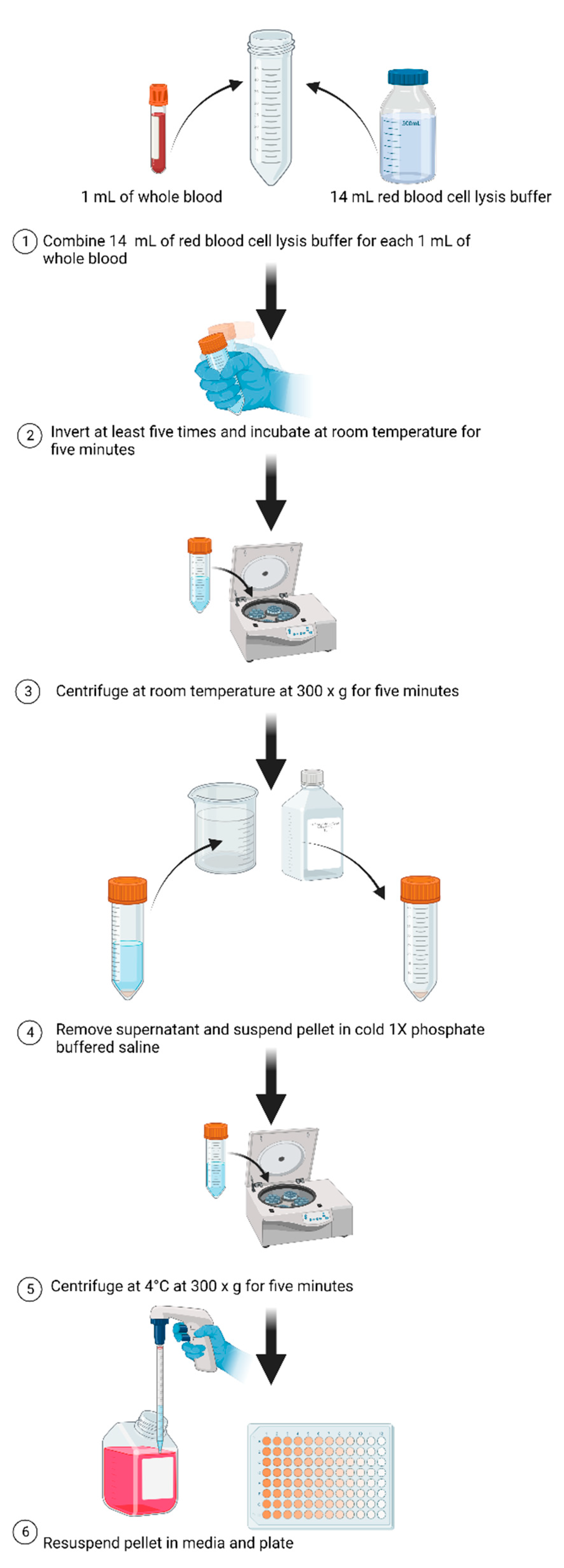

2.2. Preparation of Blood Samples

2.3. Proliferation

2.4. Assessment of Proliferation

2.5. DNA Damage and Repair

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

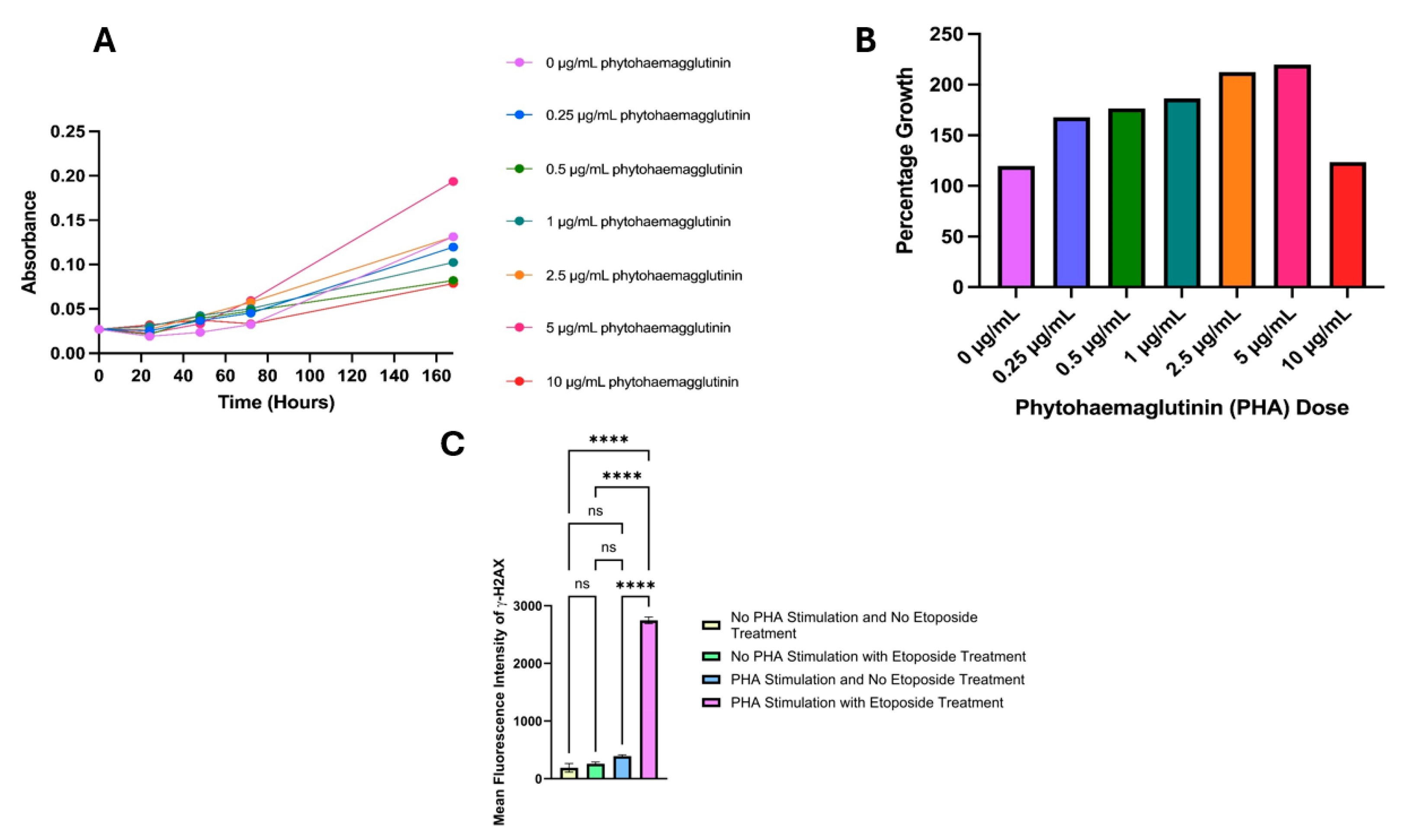

3.1. Proliferation Dose Selection

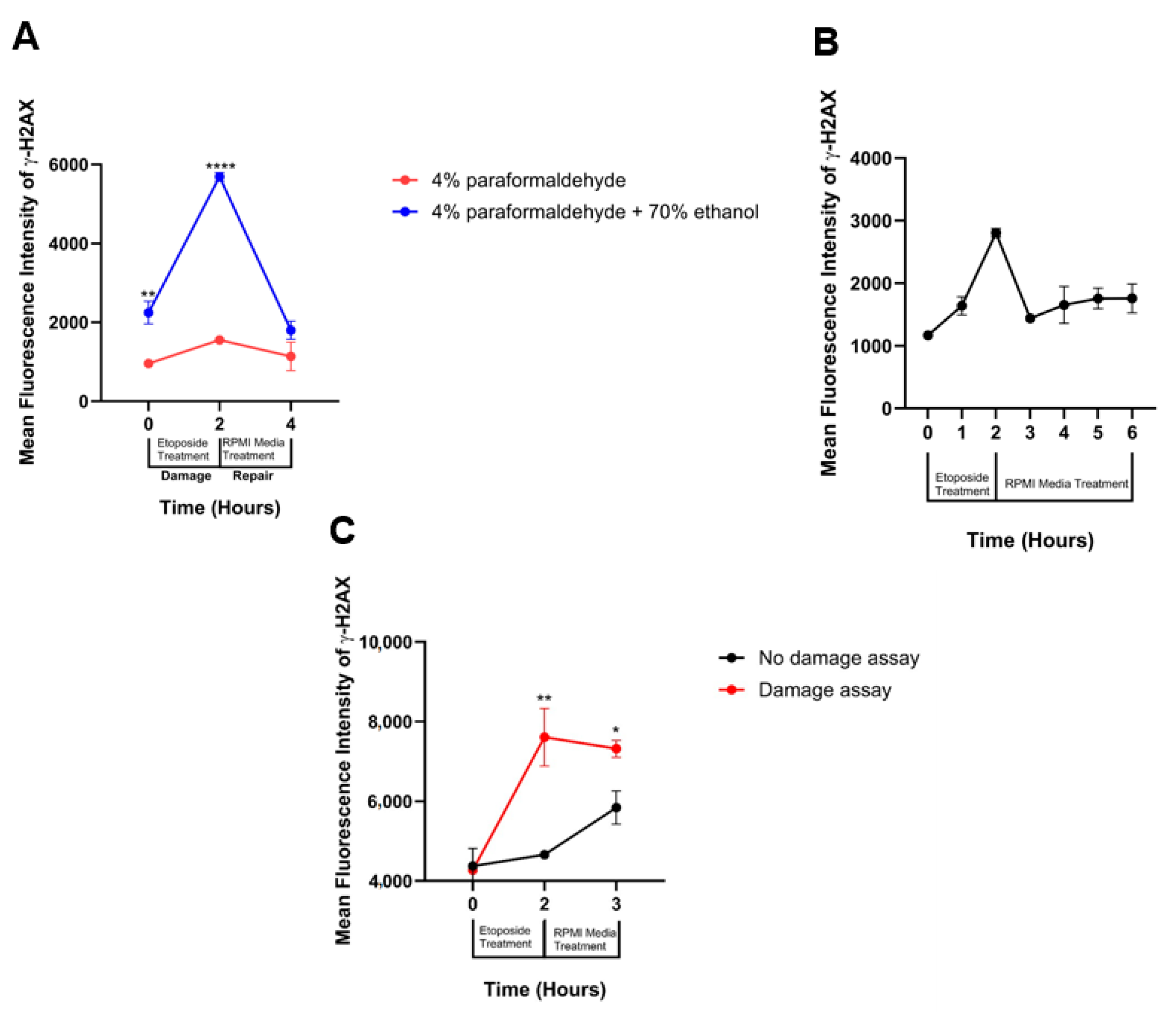

3.2. Fixation Selection

3.3. DNA Damage Repair Window Selection

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Raavi, V.; Perumal, V.; Paul, S.F. Potential application of γ-H2AX as a biodosimetry tool for radiation triage. Mutat. Res./Rev. Mutat. Res. 2021, 787, 108350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Najafi, M.; Fardid, R.; Hadadi, G.; Fardid, M. The mechanisms of radiation-induced bystander effect. J. Biomed. Phys. Eng. 2014, 4, 163. [Google Scholar]

- Stefanou, D.T.; Bamias, A.; Episkopou, H.; Kyrtopoulos, S.A.; Likka, M.; Kalampokas, T.; Photiou, S.; Gavalas, N.; Sfikakis, P.P.; Dimopoulos, M.A.; et al. Aberrant DNA damage response pathways may predict the outcome of platinum chemotherapy in ovarian cancer. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0117654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lampert, E.J.; Cimino-Mathews, A.; Lee, J.S.; Nair, J.; Lee, M.J.; Yuno, A.; An, D.; Trepel, J.B.; Ruppin, E.; Lee, J.M. Clinical outcomes of prexasertib monotherapy in recurrent BRCA wild-type high-grade serous ovarian cancer involve innate and adaptive immune responses. J. Immunother. Cancer 2020, 8, e000516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosking, H.; Pederick, W.; Neilsen, P.; Fenning, A. Considerations for the Use of the DNA Damage Marker γ-H2AX in Disease Modeling, Detection, Diagnosis, and Prognosis. Aging Cancer 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, J.; Zhao, X.; Hou, R.; Wang, Y.; Chang, W.; Liang, N.; Liu, Y.; Xing, J.; Cao, Y.; Li, X.; et al. Comparison of two commonly used methods for stimulating T cells. Biotechnol. Lett. 2019, 41, 1361–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beliakova-Bethell, N.; Hezareh, M.; Wong, J.K.; Strain, M.C.; Lewinski, M.K.; Richman, D.D.; Spina, C.A. Relative efficacy of T cell stimuli as inducers of productive HIV-1 replication in latently infected CD4 lymphocytes from patients on suppressive cART. Virology 2017, 508, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Huang, Y.; Jiang, H.; Zhang, D.; Yang, Y.; Geng, X.; Li, B. Functional differences and similarities in activated peripheral blood mononuclear cells by lipopolysaccharide or phytohemagglutinin stimulation between human and cynomolgus monkeys. Ann. Transl. Med. 2021, 9, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith-Norowitz, T.A.; Abdelmajid, H.; Yin, C.; Choice, S.; Joks, R.; Kohlhoff, S. Effect of Dimethyl Sulfoxide on B Cells in PHA-Stimulated PBMC from Adult Subjects. A Pilot Study. Ann. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2023, 53, 126–129. [Google Scholar]

- Chuchawankul, S.; Khorana, N.; Poovorawan, Y. Piperine inhibits cytokine production by human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Genet. Mol. Res. 2012, 11, 617–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruni, E.; Reichle, A.; Scimeca, M.; Bonanno, E.; Ghibelli, L. Lowering etoposide doses shifts cell demise from caspase-dependent to differentiation and caspase-3-independent apoptosis via DNA damage response, inducing AML culture extinction. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, F.; Hao, P.; Zhang, X.; Hu, H.; Jiang, D.; Yin, A.; Wen, L.; Zheng, L.; He, J.Z.; Mei, W.; et al. Etoposide-induced DNA damage affects multiple cellular pathways in addition to DNA damage response. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 24122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sunter, N.J.; Cowell, I.G.; Willmore, E.; Watters, G.P.; Austin, C.A. Role of Topoisomerase II in DNA Damage Response following IR and Etoposide. J. Nucleic Acids 2010, 2010, 710589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menendez, D.; Anand, J.R.; Murphy, C.C.; Bell, W.J.; Fu, J.; Slepushkina, N.; Buehler, E.; Martin, S.E.; Lal-Nag, M.; Nitiss, J.L.; et al. Etoposide-induced DNA damage is increased in p53 mutants: Identification of ATR and other genes that influence effects of p53 mutations on Top2-induced cytotoxicity. Oncotarget 2022, 13, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vlachogiannis, N.I.; Ntouros, P.A.; Pappa, M.; Kravvariti, E.; Kostaki, E.G.; Fragoulis, G.E.; Papanikolaou, C.; Mavroeidi, D.; Bournia, V.-K.; Panopoulos, S.; et al. Chronological Age and DNA Damage Accumulation in Blood Mononuclear Cells: A Linear Association in Healthy Humans after 50 Years of Age. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 7148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Nasrallah, N.; Zhou, H.; Smith, P.A.; Sears, C.R. DNA Repair Capacity for Personalizing Risk and Treatment Response−Assay Development and Optimization in Human Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMCs). DNA Repair 2022, 111, 103274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schumann, S.; Scherthan, H.; Pfestroff, K.; Schoof, S.; Pfestroff, A.; Hartrampf, P.; Hasenauer, N.; Buck, A.K.; Luster, M.; Port, M.; et al. DNA damage and repair in peripheral blood mononuclear cells after internal ex vivo irradiation of patient blood with 131 I. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2022, 49, 1447–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Quan, N. Immune cell isolation from mouse femur bone marrow. Bio-Protocol 2015, 5, e1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, J.; Johnson, J.; Hosking, H.; Walsh, K.; Neilsen, P.; Naiker, M. In vitro cytotoxic properties of crude polar extracts of plants sourced from Australia. Clin. Complement. Med. Pharmacol. 2022, 2, 100022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, J.; Johnson, J.; Hosking, H.; Hoyos, B.E.; Walsh, K.B.; Neilsen, P.; Naiker, M. Bioassay guided fractionation protocol for determining novel active compounds in selected Australian flora. Plants 2022, 11, 2886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norian, R.; Delirezh, N.; Azadmehr, A. (Eds.) Evaluation of proliferation and cytokines production by mitogen-stimulated bovine peripheral blood mononuclear cells. In Veterinary Research Forum; Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Urmia University: Urmia, Iran, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mandarapu, R.; Ajumeera, R.; Venkatesan, V.; Prakhya, B.M. Proliferation and TH1/TH2 cytokine production in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells after treatment with cypermethrin and mancozeb in vitro. J. Toxicol. 2014, 2014, 308286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hosking, H.; Pederick, W.; Neilsen, P.; Fenning, A. Optimisation of Ex Vivo Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cell Culture and DNA Double Strand Break Repair Kinetics. LabMed 2024, 1, 5-13. https://doi.org/10.3390/labmed1010003

Hosking H, Pederick W, Neilsen P, Fenning A. Optimisation of Ex Vivo Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cell Culture and DNA Double Strand Break Repair Kinetics. LabMed. 2024; 1(1):5-13. https://doi.org/10.3390/labmed1010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleHosking, Holly, Wayne Pederick, Paul Neilsen, and Andrew Fenning. 2024. "Optimisation of Ex Vivo Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cell Culture and DNA Double Strand Break Repair Kinetics" LabMed 1, no. 1: 5-13. https://doi.org/10.3390/labmed1010003

APA StyleHosking, H., Pederick, W., Neilsen, P., & Fenning, A. (2024). Optimisation of Ex Vivo Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cell Culture and DNA Double Strand Break Repair Kinetics. LabMed, 1(1), 5-13. https://doi.org/10.3390/labmed1010003